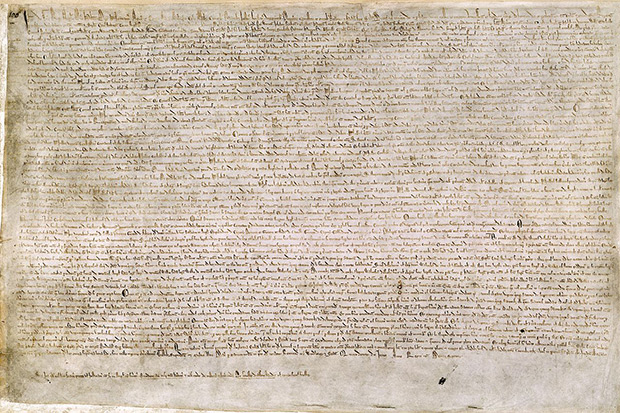

2015 marks the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta. Index on Censorship magazine’s winter issue has a special report that examines all ways in which the document affected modern freedoms. Here John Crace kicks us off with a tongue-in-cheek trip through history

Call it a free for all. Call it an innate sense of fair play. Call it what you will, but the English had always had a way of making their feelings known to a monarch who got a bit above himself by hitting the country for too much money in taxes or losing overseas military campaigns or both. They rebelled. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t but it was the closest medieval England had to due process. Then came John, a king every bit as unloved – if not more so – as any of his predecessors; a ruler who had gone back on many of his promises and was doing his best to lose all England’s French possessions and all of a sudden the barons had a problem. There wasn’t any obvious candidate to replace him.

So instead of deposing him, they took him on by limiting his powers.

Kings never have much liked being told what to do and John was no exception. If he could have got out of cutting a deal with the barons he would have done. But even he understood that impoverishing the people he relied on to keep him in power hadn’t been the cleverest of moves, and so he reluctantly agreed to take part in the negotiations that led to the sealing of The articles of the Barons – later known as Magna Carta – at Runnymede on 15 June 1215. Which isn’t to say he didn’t kick and scream his way through them before agreeing to the 61 demands which were the bare minimum for his remaining in power. He did, though, keep his fingers cunningly crossed when the seal was being applied. As soon as the barons had left London, King John announced — with the Pope’s blessing — that he was having no more to do with it. The barons were outraged and went into open rebellion, though dysentery got to King John before they did and he died the following year. Don’t shit with the people, or the people shit with you. Or something like that.

With the original Magna Carta having lasted barely three months, there were some who reckoned they could have saved themselves a lot of time and effort by topping King John rather than negotiating with him. But wiser – or perhaps, more peaceful – counsel prevailed and its spirit has endured through various subsequent mutations – most notably the 1216 Charter, The Great Charter of 1225 and the Confirmation of Charters of 1297 and has widely come to be seen as the foundation stone of constitutional law, both in England and many countries around the world. It was the first time limitations had been formally placed on a monarch’s power and the rights of citizens to the due process of law and trial by jury had been affirmed. Well, not quite all citizens. When the various charters talked of the rights of Freemen, it didn’t mean everyone; far from it. Freemen just meant that small class of people, below the barons, who weren’t tied to land as serfs. The Brits have never liked to rush things. They like their revolutions to be orderly. The underclass would just have to wait.

Magna Carta and its derivative charters were never quite the symbols of enlightened noblesse oblige they are often held to be. The noblemen didn’t sit around earnestly thinking about how they could turn England into a communal paradise. What was the point of having fought and back-stabbed your way to the top only to give power away to the undeserving? The charters were matters of political expedience. The nobles needed the Freemen on their side in their face-off with the king and an extension of their rights was the bargaining chip to secure it. Benevolence never really entered the equation. Nor was Magna Carta ever really a legal constitutional framework. Even if King John hadn’t decided to ignore it within months, it would still have been virtually unenforceable as it had no statutory authority. It was more wish-list than law.

Ironically, though, it is Magna Carta’s weaknesses that have turned out to have guaranteed its survival. Over the centuries, Magna Carta has become the symbol of freedom rather than its guarantor as different generations have cherry-picked its clauses and interpreted them in their own way. While wars and poverty might have been the prime catalyst for the Peasant’s Revolt against King Richard II in 1381, it was Magna Carta to which the rebellion looked for its intellectual legitimacy. The Freemen were now seen to be free men; constitutional rights were no longer seen as residing in the few. The King and his court were outraged that the peasants had made such an elementary mistake as to mistake the implied capital F in Freemen for a small f and the leaders were executed for their illiteracy as much as their impudence.

Bit by bit, starting in 1829 with the section dealing with offences against a person, the clauses of Magna Carta were repealed such that by 1960 only three still survived. Some, such as those concerning “scutage” — a tax that allowed knights to buy out of military service — and fish weirs, had become outdated; others had already been superseded by later statutes. Two of those that remained related to the privileges of both the Church of England and the City of London — a telling insight into the priorities of the establishment. Those who still wonder, following the global financial collapse of 2008, why the bankers were allowed to get away with making up the rules to suit themselves need look no further than Magna Carta. The bankers had been used to getting away with it for the best of 800 years. You win some you lose some.

The survival of clause 39 of the original Magna Carta has been rather more significant for the rest of us. “No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.” Or in layman’s terms, due process: the legal requirement of the state to recognise and respect all the legal rights of the individual. The guarantee of justice, fairness and liberty that not only underpins – well, most of the time – the UK’s constitutional framework, but those of many other countries as well.

Britain has no written constitution. Not because parliament has been too lazy to get round to drawing one up, but because one is already assumed to be in the lifeblood of every one living in Britain. Queen Mary may have had “Calais” written on her heart, but the rest of us all have “Magna Carta” inscribed there. It can be found on the inside of the left ventricle, for those of you who are interested in detail. Other countries haven’t been so trusting in the genetic inheritance of feudal England and have insisted on getting their constitutions down in non-fugitive ink.

That Magna Carta has also been the lodestone for the constitutions of so many other countries, most notably the USA, is less a sign of the global reach of democratic principles – much as that might resonate with romantic ideals of justice — than of the spread of British people and British imperial power. After the Mayflower arrived in what became the USA from Plymouth in 1620, the first settlers’ only reference point for the establishment of civil society was Magna Carta. The settlers had a lot of other things on their minds in the early years — most notably their own survival and the share price of British American Tobacco — and they hadn’t got time to dream up their own bespoke constitution. If they had, they might have come up with something that abolished slavery and gave equal rights to black people sometime before the 1960s. So they settled for an off-thepeg version of Magna Carta, with various US amendments. And some poor spelling. In 1687 William Penn published the first version of Magna Carta to be printed in America. By the time the fifth amendment — part of the bill of rights – was ratified four years after the original US constitution in 1791, Magna Carta had been enshrined in American law with “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.”

The fact that the American idea of Magna Carta was not one that would necessarily have been recognised in Britain was neither here nor there. For the Americans, the notion of the rights of a people to govern themselves was more than something that had been fought for over many centuries – a gradual taking back of power from an absolute ruler — that had been ratified on paper. They were fundamental rights that pre-existed any country and transcended national borders. And even if there was no one left alive on Earth, these rights would remain. They might as well have been handed down by God, though it’s probably just as well Adam hadn’t read the sections on the right to defend himself and bear arms. If he had shot the serpent, the whole history of the world might have been very different. As it is, when the Americans took on the British in the War of Independence, they weren’t fighting against a colonial overlord so much as for their basic rights to freedom.

The distinction is a subtle but important one. For though the more recent constitutions of former British colonies, such as Australia, India, Canada and New Zealand, more closely reflected the way Magna Carta was understood back in the mothership, those interpretations of it were still very much a product of their time. As a historical document, Magna Carta remains fixed in the 13th century: a practical solution to the problem of an iffy king. But as a concept it is a shifting, timeless expression of the democratic ideal. It can mean and explain anything. Up to and including that Britain always knows best.

Yet the appeal of Magna Carta endures and it remains the gold standard for democracy in any debate. Whatever side of it you happen to be on. British eurosceptics argue that the UK’s continuing membership of the European Union threatens the very parchment on which it was written; that Britain is being turned into a serf by a European despot. Pro Europeans argue that the EU does more than just enshrine the ideals of Magna Carta, it turns the most threatened elements of it into law.

Eight hundred years on, Magna Carta remains a moving target. Something to be aspired to but never truly attained. A highly combustible compound of idealism and pragmatism. Somehow, though, you can’t help feeling that King John and the feudal barons would have understood that. And approved.

This article is from the Winter 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine as 1215 and all that.

This article was originally posted on Dec 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org