Greece: Can reborn ERT deliver on the promise of a truly public broadcaster?

On June, 11 2015 the Greek public TV went back to its old name “ERT”, exactly two years after its abrupt closure by the previous conservative-led government.

In June 2013 the government shut down the TV station and fired some 2,600 media workers, accusing the public broadcaster of corruption and mismanagement. Although ERT’s “sins” and disfunction were well known, the real reason behind its brutal shutdown was to meet layoff quotas laid down by Greece’s international creditors.

A few months after shuttering ERT, the government opened the New Hellenic Radio, Internet and Television (NERIT), a shrunken public broadcaster that hired employees under 3-month contracts. The budget was cut from around 300 to 100 million euros.

In April 2015, the three-month-old left wing government led by Syriza abandoned the name “NERIT” and reinstated “ERT”, which fulfilled a pre-electoral promise. It also announced that any of ERT’s 2,600 employees who wished to return to work could do so. A law setting the budget of the broadcaster at 60 million euros a year would be covered by a licence fee of three euros a month.

Under the last government, ERT was derided as bloated and biased.

“ERT is a case of an exceptional lack of transparency and incredible extravagance. This ends now,” government spokesman Simos Kedikoglou had said in a statement aired on ERT back in June 2013, announcing the government’s intention “to shut down ERT”.

On the evening of the 11 June 2013, the Greek state TV went dark for the first time since 1938, triggering outrage but also support for the shocked Greek journalists and people by the international community and press, who saw this event as example of censorship and violation of freedom of speech in crisis-stricken Greece.

“When the microphone of a journalist is cut off, it’s like the voice of democracy being silenced. This has just been brutally done to 1,300 journalists – brutally in all senses because the Greek government has sent in the police to cut off a broadcaster and stop journalists from doing their job. That is the voice of democracy, the counterweight, a pressure group, that the government, the economic power is gagging”, European Broadcast Union President Jean-Paul Philippot commented that day condemning the Greek government’s overnight shutdown of its national broadcaster ERT as an act of violence and “the worst kind of censorship”.

But, this act was not the first and only government intervention in and censorship of the state TV. An example, is that in 2012, Kostas Arvanitis and Marilena Katsimi, presenters of news-magazine “Morning Information” on NET TV were removed from the programme due to comments about Minister of Citizen Protection Nikos Dendias.

Nikos Dendias had threatened to sue The Guardian over an article about a group of Greek protesters being tortured by the police.

Arvanitis and Katsimi were told about being “cut” from the show by its editor-in-chief who was informed about the decision by the general director of ERT, just hours after the broadcast on Monday morning.

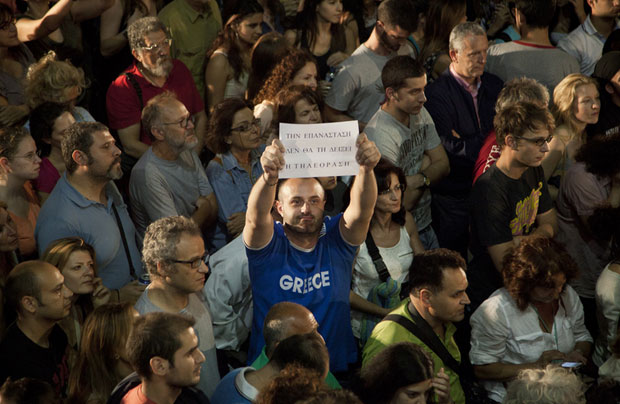

The closure of ERT triggered a wave of protests against the government’s austerity policies, during which demonstrators sent a clear message in favour of a truly public — not state — broadcaster. In the wake of the silencing of ERT, the newly unemployed journalists banded together to launch ERT Open. Ahead of the election that swept Syriza to power, the party promised a modern public broadcaster free of constraints. In announcing the reopening of ERT, the government promised “the actual fulfillment of the objectives of the public broadcasting service for information, education and entertainment of the Greek people”.

However, the new ERT relaunched amid harsh criticism from opposition parties and the press, accusing the broadcaster of promoting the left-wing government’s positions. The critics said that the reality was far from the pre-election promise of a pluralistic and objective public television station.

A government spokesperson denied any intervention and claimed that representatives of all parties were invited to participate in the first informational programmes.

According to an Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso interview with ERT’s Italy correspondent, Dimitri Deliolanes, the new government explicitly spoke of parliamentary oversight for public broadcasting. He said that for the parliament to have a control commission, as happens for example in Italy, a constitutional amendment would be needed. For this reason, the appointment of a new leadership for ERT occurred after a hearing in the parliamentary committee on transparency.

“Today ERT works well, with a very good quality standard, as competitors do not shine for sure. But the government, busy with managing the debt, has not yet managed to structure the committee. So, ERT is subject to the supervision of minister without portfolio Nikos Pappas”, Deliolanes concluded.

It remains to be seen whether Greece’s “new” public broadcaster will grow into the promised medium that is free of political intervention and the sins of the past.

|

Mapping Media Freedom

|

This article was posted on 16 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org