31 Dec 13 | News and features, Politics and Society

Journalists are known for uncovering the truth. What is less known is how these journalists gather these facts, often risking their jobs, and sometimes their lives, to discover information others are attempting to keep hidden from the world.

The Taksim Gezi Park Protest

The Gezi Park protest in Turkey made international news when, in May 2013, a sit-in at the park protesting plans to develop the area sparked violent clashes with police. What didn’t grab the attention of media workers worldwide was that at least 59 of their fellow journalists were fired or forced to quit over their reporting of the events.

The Turkish press have been long-time sufferers of the need to self-censor in an environment where the press is ultimately run by a handful of wealthy individuals. The Gezi Park protests saw a surge in the controlling influence of the Turkish media as 22 journalists were fired and a further 37 forced to quit due to their determination to cover the clashes for a national and international audience, as was their duty as journalists.

Turkey came in at 154th in the Reporters Without Borders Freedom of the Press Index 2013, a drop of six places from 2012.

Journalists imprisoned

2013 was the first year a detailed survey was carried out by Reporters Without Borders which looked into how many journalists had been imprisoned for their work; the result was shocking. One hundred and seventy eight journalists were spending time in jail for their actions, along with 14 media assistants. Perhaps more worrying was the statistic that 166 netizens had been imprisoned, those who actively supply the world with content often without being paid whilst gaining access to places that many ‘official’ journalists are banned from.

China handed out the most prison sentences during 2013 with 30 media personal serving time behind bars. Closely behind was Eritrea with 28 journalists imprisoned, Turkey with 27, and Iran and Syria handing out 20 sentences each.

Press freedom in Afghanistan

Murder, injuries, threats, beatings, closure of media organisations, and the dismissal for liking a Facebook post have all accounted towards the 62 cases of violence against the media and journalists working in Afghanistan over the past eight months. The Afghanistan Journalists Center, which collected the data from January to August 2013, has claimed that government officials and security forces, the Taliban, and illegal armed groups are behind the majority of attacks.

Of particular concern is the growing threat to female journalists who have been forced to quit their jobs after threats to their families.

According to the Afghanistan Media Law; every person has the right to freedom of thought and speech, which includes the right to seek, obtain and disseminate information and views within the limit of law without any interference, restriction and threat by the government or officials- a law Afghanistan does not appear to be upholding.

Exiled journalists

Some journalists are taking a risk every day that they go to work. They may not be killed for their reporting but that does not stop them facing imprisonment, violence, and harassment. Between June 2008 and May 2013 the CPJ found that 456 journalists were forced into exile as a means of protecting their families and themselves due to their determination to uncover the truth.

The top countries from which journalists fled included Somalia, Ethiopia and Sri Lanka with Iran topping the table having forced a total of 82 journalists into exile. Although a majority of these journalists claim sanctuary in countries like Sweden, the U.S and Kenya, only 7% of those exiled since 2008 have been able to return home.

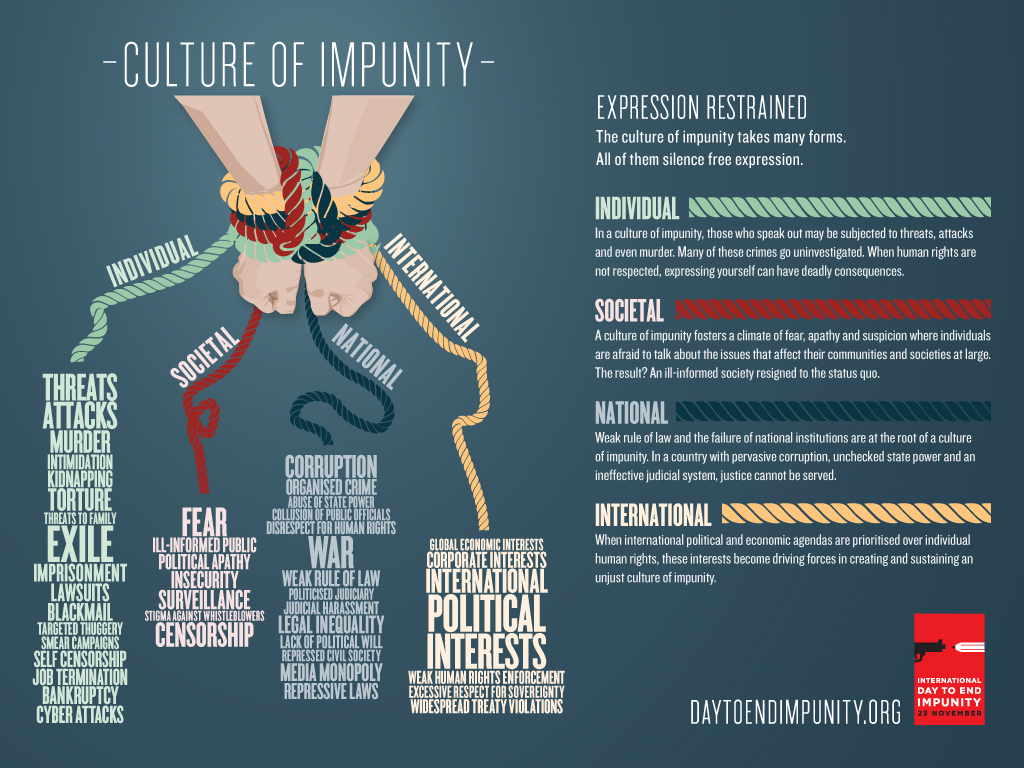

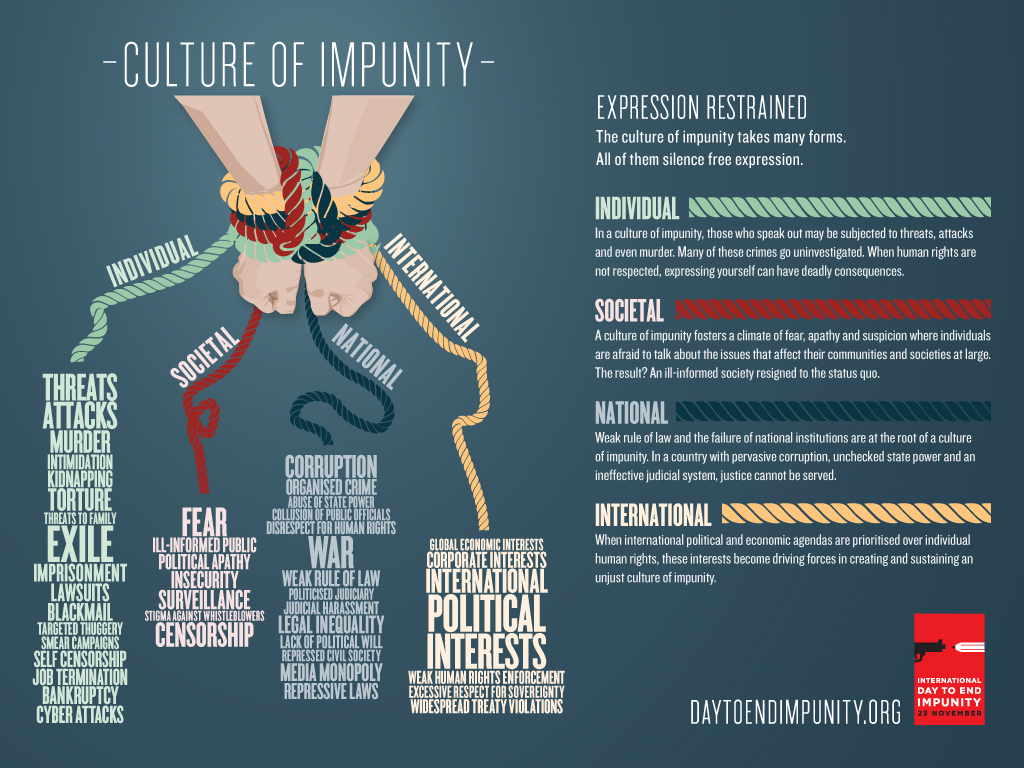

Impunity

Murder is a crime for which those involved should be punished. Yet in the case of the killing of journalists nine out of 10 killers go free. Put another way, in only five percent of cases for the murder of a journalist does the defendant receive a sentence of full justice. The most likely reason to kill a journalist is to silence them from speaking the truth to others.

IFEX, global freedom of expression network behind the International Day to End Impunity campaign said: “When someone acts with impunity, it means that their actions have no consequences. Intimidation, threats, attacks and murders go unpunished. In the past 10 years, more than 500 journalists have been killed. Murder is the ultimate form of censorship, and media are undoubtedly on the frontlines of free expression.”

27 Nov 13 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Nations

The UN has officially recognised 2 November as the International Day to End Impunity for crimes against journalists. As reported by Index, a draft resolution calling for this was put to a vote on 26 November. Co-sponsored by 80 organisations across 48 countries, it was passed by the Third Committee, which deals with human rights issues.

Index on Censorship, as part of the IFEX network, has welcomed the decision. Annie Game, IFEX Executive Director, stated: “There has never been a more dangerous time for journalists. They are being killed and imprisoned worldwide in record numbers. They face daily threats, attacks and intimidation from private individuals, non-state actors, and government officials who seek to silence them. The overwhelming majority of these crimes are committed with impunity.”

“We welcome the resolution’s call to proclaim November 2 as the International Day to End Impunity for crimes against journalists. With complete impunity in nine out of 10 cases of journalist murders worldwide, this decision does not come too soon. This is a crucial step toward guaranteeing that individual journalists can continue to work in the public interest without fear of reprisal, and that those who seek to silence them with violence are brought to justice.”

26 Nov 13 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Nations

The UN has been urged to officially recognise the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists as the Third Committee, dedicated to dealing with human rights issues, will today be asked to vote on a draft resolution.

The resolution, backed by at least 48 countries, is based on the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, approved on 12 April 2012, which saw United Nations agencies work with member states towards a free and safe working environment for journalists. If successful, the UN Secretary General will present a report on the implementation of the resolution at the next General Assembly 2014, with 2 November officially being recognised as the official UN International Day to End Impunity.

Co-sponsored by 80 organisations and backed by countries including the United States — and even Azerbaijan and Colombia — the draft resolution calls for the acknowledged ‘condemnation of all attacks and violence against journalists and media workers, such as torture, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances and arbitrary detention, as well as intimidation and harassment in both conflict and non-conflict situations’.

Index on Censorship as a founding member of IFEX has been supporting the International Day to End Impunity since its launch in 2010 which has seen the 23 November recognised as the day for campaign. Annie Game, IFEX Executive Director, stated: “This is a positive move forward because IFEX members acknowledged that making the International Day to End Impunity an official UN day can help to raise the global profile of the issue. Every year, a growing number of IFEX members and concerned individuals take part in this campaign that strikes at the very roots of the problem. Having the UN acknowledge the importance of this issue will help us broaden our reach and turn up the volume on the call to end impunity.”

The draft resolution also:

• acknowledges ‘the specific risks faced by women journalists in the exercise of their work, and underlining, in this context, the importance of taking a gender-sensitive approach when considering measures to address the safety of journalists’;

• the acknowledgement that ‘journalism is continuously evolving to include inputs from media institutions, private individuals and a range of organisations that seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, online as well as offline, in the exercise of freedom of opinion and expression, in accordance with article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights’;

• and ‘urges Member States to do their utmost to prevent violence against journalists and media workers, to ensure accountability through the conduct of impartial, speedy and effective investigations into all alleged violence against journalists and media workers falling within their jurisdiction, and to bring the perpetrators of such crimes to justice and to ensure that victims that access to appropriate remedies’.

The full draft resolution can be seen here.

This article was originally published on 26 Nov 2013 at indexcensorship.org

22 Nov 13 | Americas, Asia and Pacific, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

Tomorrow is International Day To End Impunity. “When someone acts with impunity, it means that their actions have no consequences” explains IFEX, the global freedom of expression network behind the campaign. Since 1992, 600 journalists have been killed with impunity — that is 600 lives taken with all or some of those culpable not being being held responsible. Countless others — writers, activists, musicians — have joined their ranks, simply for exercising their right to freedom of expression.

This year has only added to the grim statistics. By the middle of January, six journalists had already been murdered. We are now getting close to the end of 2013, and 73 more journalists and two media workers have suffered the same fate — 48 in cases directly connected to their work, 25 with motives still unconfirmed. Out of these, 15 were killed without anyone — perpetrators or masterminds — convicted.

Russia is notorious for its culture of impunity. In July this year, Akhmednabi Akhmednabiev, a Russian journalist reporting on human rights violations in the Caucasus, was shot dead. In 2009 he had been placed on an “execution list” on leaflets distributed anonymously, and had in the past also received death threats. In January he survived an assassination attempt which local authorities reportedly refused to investigate. His case is still classed as murder with impunity.

Pakistan is also an increasingly dangerous place to work as a journalist. Twenty seven of the 28 journalists killed in the past 11 years in connection with their work have been killed with impunity. In the last year alone, seven journalists have been murdered. Express Tribune journalist Rana Tanveer told Index he has received death threats and been followed for reporting on minority issues. In October, Karak Times journalists Ayub Khattak was gunned down after filing a report on the drugs trade.

In July, Honduran TV commentator Aníbal Barrow was kidnapped together with his family and a driver. The others were released, but after two weeks, Barrow’s body was found floating in a lagoon. He was the second journalists with links to the country’s president Porfirio Lobo Sosa — they were close friends — to have been killed over the past two years. Four members of the criminal group “Gordo” were detained in connection with the case, but at one point, there were at least three other suspects on the run.

In September, Colombian lawyer and radio host Édison Alberto Molina was shot four times while riding on his motorcycle with his wife. His show “Consultorio Jurídico” (The Law Office), aired on community radio station Puerto Berrío Stereo, and often took on the topic of corruption. The Inter American Press Association in October called on authorities to open “a prompt investigation into the murders” of him and news vendor and occasional stringer José Darío Arenas, who was also killed in September.

Meanwhile in Mexico, a country for many synonymous with impunity for crimes against the media, three journalists were murdered in 2013. The state public prosecutor’s offices has yet to announce any progress in the cases of Daniel Martínez Bazaldúa, Mario Ricardo Chávez Jorge and Alberto López Bello, or disclose whether they are linked to their work. Notorious criminal syndicate Zetas took responsibility for the murder of Martínez Bazaldúa and warned the police about investigating the case. He was a society photographer and student, only 22 at the time of his death. Chavez Jorge, founder of an online newspaper, disappeared in May and his body was found in June, but in August the state attorney’s office said they did not have a record of his death. López Bello was a crime reporter who had published stories on the drugs trade.

This year, 20 journalists — from Naji Asaad in January to Nour al-Din Al-Hafiri in September — have also lost their lives covering the ongoing tragedy of the Syrian civil war. Their loved ones, like those of all the civilians killed, will have to wait for justice.

It is also worth noting that while an unresolved or uninvestigated murder is the most serious and devastating manifestation of impunity, it is not the only one. Across the world, journalists are being attacked and intimidated without consequences. In August there was a two-hour long raid on the home of Sri Lankan editor and columnist Mandana Ismail Abeywickrema, who recently started a journalists’ trade union. Despite her receiving threats related to her work prior to the attack, it was labelled a robbery by the police. Bahraini citizen journalist Mohamed Hassan experienced similar incident, also in August, when he was arrested and his equipment seized during a night-time raid. His lawyer Abdul Aziz Mosa was also detained and his computer confiscated, after tweeting about his client being beaten. In October, a group of Azerbaijani journalists were attacked by a pro-government mob while covering an opposition rally in the town of Sabirabad. One of the journalists, Ramin Deko, told Index of regular threats and intimidation.

International Day To End Impunity is a time to reflect on these staggering figures and the tragic stories behind them. More importantly, however, it represents an opportunity to stand up and demand action. Demand that Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto, Pakistan’s President Mamnoon Hussain and the rest of the world’s leaders provide justice for those murdered. Demand an end to the culture of impunity in which journalists, writers, activists, lawyers, musicians and others can be intimidated, attacked and killed simply for daring to speak truth to power. Visit the campaign website to see how you can take action.