Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100124″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Flying from Moscow to Simferopol is quick and relatively affordable if you’re travelling out of season, but according to Ukrainian law it’s also illegal. After the 2014 Russian annexation of the peninsula, Ukraine passed a law that prohibits travelling to Crimea via Russia. Violating it can lead to a fine and a ban on entering Ukraine.

Journalists who travel to Crimea via Ukraine need the necessary documentation to work in a territory that is de facto controlled by Russia. In addition to a Russian accreditation and work visas — obtained at the end of a long and demanding process that can prove particularly difficult for freelancers — journalists also need to make their way to Kyiv and present a series of documents to Ukraine’s ministry of information and immigration service, to obtain a permit to enter Crimea, which takes a minimum of one or two days. Then they can head south and make their way to what has become the border with Crimea, 668 kilometres away. Once on the peninsula, they are usually interviewed by FSB officers.

Anton Naumliuk, a Russian journalist who covers Crimea for Radio Liberty, has been travelling to the peninsula about six times a year recently, always via Ukraine. He says he’s noticed that the procedure on the Ukrainian side is becoming simpler and faster. He’s also seen the border gradually built up. “Two years ago there was nothing, just the ground,” he said. Now there’s portacabins and fences. In the summer, there can be long queues.

Journalists often encounter difficulties on the Russian side, he explained. “[FSB officers] ask you who you’ll meet. This interrogation can take hours. If the journalist is quite well-known they try not to do it. If you’re young, if you’re Ukrainian, or carry equipment, you’re more likely to be interrogated. It can be quite nerve-wracking.”

Journalists can be asked to display the content of their phones or computers, although, according to Russian law, they cannot be forced to provide passwords to law enforcement. Officers can search hard drives or flashcards. This means journalists are advised to wipe any sensitive information which could compromise their sources before crossing the border. FSB agents have also been known to ask journalists for their phones’ IMEI number, which could allow them to track the person’s movements when they are reporting in the peninsula.

On my way back from a recent reporting trip to Crimea I met Tetiana Pechonchyk, who monitors human rights violations in Crimea at the Human Rights Information Centre in Kyiv. Her organisation has been campaigning for an easier access for journalists to the peninsula, in a context where coverage by Ukrainian journalists has gradually become near to impossible. “Almost no Ukrainian journalist is able to work in Crimea. A lot of Ukrainian journalists who covered the occupation and persecutions connected to it left Crimea. Ten Crimean media outlets moved to mainland Ukraine with their staff. They continue to cover Crimea but a majority of the websites are blocked on the peninsula, while not being blocked in Russia,” she said.

According to the Human Rights Information Centre’s monitoring, the number of assaults against journalists in Crimea has gone down, but for Pechonchyk, this does not mean much: “They pushed most of independent journalists out. Once you’ve emptied the field then you have no one to repress. They were lots of physical attacks in 2014. In 2015 Russia used legal tools against media outlets. They wouldn’t give a Russian license to outlets. Then they picked journalists who work for the Ukrainian media and terrified them one by one. Small media and bloggers have started appearing in Crimea. The role of professional journalists has been taken over by average citizens who film videos of searches in Tatar houses, go to politically motivated trials to cover them. Now authorities have started persecuting citizen journalists as well.”

Naumliuk began reporting from Crimea because he saw what was taking place there as a continuation of the war in Donbass. “It’s a lot more important than it seems at first glance and offers some understanding into what happened after the breakup of the Soviet Union and what will happen to such a big territory, in places like Belarus and Kazakhstan,” he said. He mostly covers court cases, with a focus on persecutions against Tatars. He says very few foreign outlets work with him regularly, they’ll only ask for his help if something happens.

“[Without constant coverage] it’s super difficult to understand the situation. There’s no human rights organisations working on the ground and very few independent journalists. Very little information on repression against political prisoners goes out. For this reason, it seems nothing is happening in Crimea. It’s all very quiet. But if you speak with Tatars the picture changes. A majority of kids live without their father because of what has been happening,”Naumliuk said.

“I think that not enough journalists go, and that’s there’s not enough stories coming from Crimea, because of the travel,” Ola Cichowlas, who recently travelled via Ukraine to spend two days reporting in Crimea for the Agence France Presse, said in an interview.

“Meanwhile, the world has gotten tired of the story,” Pechonchyk said. Foreign journalists often come for the anniversary of the annexation, do a quick story and then leave.

According to the State Migration Service of Ukraine, 106 foreign journalists have travelled to Crimea via Ukraine between 2015 and March 2018.

In this context, the Human Rights Information Centre and other organisations have tried to push for a facilitated access for foreign journalists who travel to Crimea, but also for aid workers and lawyers for whom it can take much longer to obtain a permit. “The first issue in terms of access is security,” says Pechonchyk. “For a foreign journalist it’s safer to come to Crimea via the Russian Federation than enter via mainland Ukraine. You’re almost always interrogated by the FSB when you go via Ukraine, with a higher risk of being put under surveillance. If you fly to Crimea from Moscow you violate Ukrainian law but it’s safer.”

Pechonchyk believes the process enabling foreign journalists to travel to Crimea should be made simpler: “It shouldn’t be a permission, but a notification. People should be allowed to do it from abroad, via a consulate or an embassy through an online form, and they should be able to apply in English – it’s all in Ukrainian at the moment. This should be a multi-entry permit and the number of categories able to get it should be extended.” At the moment, the list only includes journalists, human rights defenders, people working for international organisations, travelling for religious purposes, to visit relatives or people who have relatives buried in Crimea. Researchers and filmmakers, for instance, are not included and struggle to go to Crimea legally.

Pechonchyk also believes there should be exceptional cases – emergencies – where journalists and lawyers are allowed to travel from Russia, to attend a trial, or report on an arrest, for instance. The existing legislation offers little clarity and seems to be mostly applied when Ukraine wants to punish individuals who supported the annexation, as happened in 2017 when they banned a Russian singer who was to take part in the Eurovision and had performed in Crimea.

But there seems to be little room for a debate on this in Ukrainian society at the moment. Difficulties of access also apply to journalists who visit the self-proclaimed separatist republics of Donetsk or Luhansk, who need a series of accreditations from the Ukrainian and the separatist side, are not supposed to enter the separatist republics from Russia, and can face backlash once they have travelled to the republic. This is what happened when in May 2016, personal information of journalists having visited DNR and LNR was leaked to Myrotvorets, a Ukrainian website known to be supported by Ukrainian police and secret services. The leak included journalists from more than 30 media outlets, who had been merely covering the war on the rebel side but were depicted by nationalists as “collaborating with terrorists”. No one was prosecuted for the leak.

Johann Bihr, who covers Eastern Europe for Reporters Without Borders, told Index: “It’s important that foreign journalists keep heading to Crimea and going back there. And we encourage Russia and Ukraine to facilitate access for journalists. If they fail to do so we face some kind of double penalty, where Crimea is abandoned by the international community because it has not been recognised and turns into an information black hole.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1525192972009-6f6057be-6973-0″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

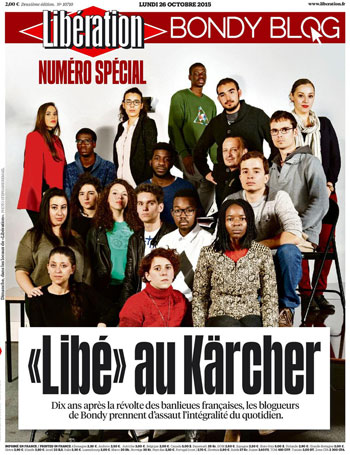

The cover of a special issue of Libération done in collaboration with the Bondy Blog, 10 years after the October 2005 riots.

This January, the trial of a police officer who had been accused of the 2012 shooting a man in the back took place near Paris. The victim was called Amine Bentounsi and was of North African origin. At the end of the proceedings, the police officer was cleared.

Journalists wrote that, with Bentounsi’s relatives present, as well as members of the police who had come to support their colleague, the atmosphere was tense. They also reported that a freelance journalist of Northern African origin called Nadir Dendoune suffered from discrimination in court, when he was the only one to be asked for his press card by a police officer while sitting among fellow journalists.

“It was 9:35am and I was sitting among other journalists when some police officers approached me, asking to see my press card. I said I’d show it to them if they asked the others as well. But the defense attorney requested silence so I decided not to make a fuss and showed my card. At noon, one of my female colleagues went to ask the officer why he had asked for my card and he said it was because he didn’t know me, except I probably come more often than her,” Dendoune told Index on Censorship.

Dendoune has worked as a journalist in print and TV for 10 years. He says he is constantly asked for his press card while on the job.

“In 2008 or 2009, I was covering something that had happened in Bondy. There must have been around 40 journalists. A police officer came to see me and told me that only journalists were allowed to be there. In France, some seem to think that you can’t be an Arab and a journalist.” That this would be the case is not suprising in a country where arbitrary and discriminatory stop and searches are usual, he said. During the presidential campaign, François Hollande promised police officers would hand receipts after a stop and search, but this promise, which was seen as an important step to improve relationships between the police and the ethnically diverse inhabitants of France, was soon dropped.

France doesn’t collect ethnic statistics, which means there is no data on the representation of minorities in society.

“[The lack of ethnic stats] seems to make it harder to put words on this”, journalist Widad Kefti told Index. She learned the ropes of journalism at the Bondy blog, a site which was created after the death of teenagers Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré in Clichy-sous-bois sparked riots in France’s suburbs in 2005. The Bondy blog has been instrumental as an incubator of new voices.

Last October, 10 years after Benna and Traoré’s deaths, Libération published an anniversary issue in collaboration with the Bondy blog, which included Kefti’s “Open letter to newsroom directors” calling on them to hire more journalists with diverse backgrounds. “I decided the tone of the article needed to be angry, angry like my generation, who are sick of being told that change takes time. People who are older than us had a softer approach, but it hasn’t worked.”

She said her piece prompted two types of reactions: “Some told me that I was speaking nonsense and that the only thing that mattered was social diversity. But some TV and print editors contacted me to say the letter had helped them realise there was a problem in their newsroom, wanting to discuss what could be done to change this.”

The classic path to becoming a reporter in France is to enroll in a journalism school, which have selective admission policies. “It’s very complicated to get in, very closed”, Kefti said. “At the Bondy blog, we created a free preparatory course for people with diverse backgrounds, which is based on social criteria, and we’ve had great results.”

She points to Ilyes Ramdani, a young blogger turned journalist from Aubervilliers, now in his early 20’s, who came first at the entrance competition of Lille journalism school and would not have applied had it not been for the Bondy Blog preparatory course.

Even graduating from journalism school is no guarantee, Kefti said. From what she has seen, the sector hires little, which has led to a precarious existence for new journalists, and made the profession less accessible to those who don’t have financial resources to pursue the career.

Kefti plans to create a think thank of French journalists coming from diverse backgrounds that will host a brunch every month to discuss terminology with journalists, as she is convinced the lack of diversity in newsroom has an impact on the way the news is being framed. Having become tired of seeing panels of white men supposedly representing the French TV audience, she also wants to create an academy to provide media training to experts of diverse ethnic backgrounds. Social media, which has democraticised influence, can help make newsrooms more diverse as French newspapers continue their transition to digital journalism, she said.

“To me, you really have to be stupid to fail to realise what a person of a diverse ethnic background can bring to a newsroom”, Kefti said.

This article was originally posted at Index on Censorship

Mapping Media Freedom

|

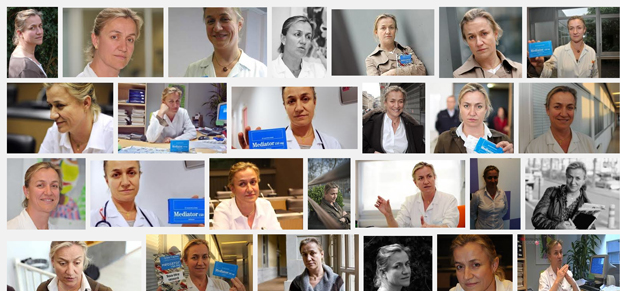

Irène Frachon is a French pneumologist who discovered that an antidiabetic drug frequently prescribed for weight loss called Mediator was causing severe heart damage.

The French term “lanceur d’alerte” [literally: “alarm raiser”], which translates as “whistleblower”, was coined by two French sociologists in the 90’s and popularised by scientific André Cicolella, a whistleblower who was fired in 1994 from l’Institut national de recherche et de sécurité [the National institute for research and security] for having blown the whistle on the dangers of glycol ethers.

While the history of whistleblowing in the United States is closely associated with the case of Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times in 1971, exposing US government lies and helping to end the Vietnam war, whistleblowing in France was first associated with cases of scientists who raised the alarm over a health or an environmental risk.

In England, the awareness that whistleblowers needed protection grew in the early 1990s, after a series of accidents (among which the shipwreck of the MS Herald of Free Enterprise ferry, in 1987, which caused 193 deaths) when it appeared that the tragedies could have been prevented if employees had been able to voice their concerns without fear of losing their job. The Public Interest Disclosure Act, passed in 1998, is one of the most complete legal frameworks protecting whistleblowers. It still is a reference.

France had no shortage of national health scandals in the 1990s, from the case of HIV-contaminated blood to the case of growth hormone. But no legislation followed. For a long time, whistleblowers were at the center of a confusion: their action was seen as reminiscent of the institutionalised denunciations that took place under the Vichy regime when France was under Nazi occupation. In fact, no later than this year, some conservative MPs managed to defeat an amendment on whistleblowers’ protection by raising the spectre of Vichy.

For Marie Meyer, Expert of Ethical Alerts at Transparency International, an anti-corruption NGO, this confusion makes little sense: “Whistleblowing is heroic, snitching cowardly”, she says.

“In France, the turning point was definitely the Mediator case, and Irène Frachon,” Meyer adds, referring to the case of a French pneumologist who discovered that an antidiabetic drug frequently prescribed for weight loss called Mediator was causing severe heart damage. In 2010, Frachon published a book – Mediator, 150mg, Combien de morts ? [“Mediator, 150mg, How Many Deaths?”] – where she recounted her long fight for the drug to be banned. Servier, the pharmaceutical company which produced the drug, managed to censor the title of the book and get it removed from the shelves two days after publication, before the judgement was overturned. Frachon has been essential in uncovering a scandal which is believed to have caused between 500 and 2000 deaths. With scientist André Cicolella, she has become one of the better-known French whistleblowers.

“What is striking is that people knew, whether in the case of PIP breast implants or of Mediator”, says Meyer. “You had doctors who knew, employees who remained silent, because they were scared of losing their job.”

This year, the efforts of various NGOs led by ex whistleblowers were finally met with results. Last January, France adopted a law (first proposed to the Senate by the Green Party) protecting whistleblowers for matters pertaining to health and environmental issues. The Cahuzac scandal, which fully broke in February and March, prompting the minister of budget to resign over Mediapart’s allegations that he had a secret offshore account, was instrumental in raising awareness and created the political will to protect whistleblowers.

For Meyer, France’s failure to protect whistleblowers employed in the public service has had direct consequences on the level of corruption in the country.

“Even if a public servant came to know that something was wrong with the financial accounts of a Minister, be it Cahuzac or someone else, how could he have had the courage to say it, and risk for his career and his life to be broken?” she says.

In June, as France discovered Edward Snowden’s revelations in the press over mass surveillance programs used by the National Security Agency, it started rediscovering its own whistleblowers: André Cicolella, Irène Frachon or Philippe Pichon, who was dismissed as a police commander in 2011 after his denunciations on the way police files were updated. Banker Pierre Condamin-Gerbier, a key witness in the Cahuzac case, was recently added to the list, when he was imprisoned in Switzerland on the 5th of July, two days after having been heard by the French Parliamentary Commission on the tax evasion case.

Three new laws protecting whistleblowers’ rights should be passed in the autumn. France will still be missing an independent body carrying out investigations into claims brought up by whistleblowerss, and an organisation to support them, like British charity Public Concern at Work does in the UK.

So far, French law doesn’t plan any particular protection to individuals who blow the whistle in the press, failing to recognise that, for a whistleblower, communicating with the press can be the best way to make a concern public – guaranteeing that the message won’t be forgotten, while possibly seeking to limit the reprisal against the messenger.