14 Jan 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases, Statements

Dean Spielmann

President

European Court of Human Rights

Council of Europe

F-67075 Strasbourg cedex

France

13 January 2014

Re: Grand Chamber referral in Delfi v. Estonia (Application no. 64569/09)

Index’s coverage: European ruling spells trouble for online comment

Dear President Spielmann and members of the panel:

We, the undersigned 69 media organisations, internet companies, human rights groups and academic institutions write to support the referral request that we understand has been submitted in the case of Delfi v. Estonia (Application No. 64569/09). Signatories to this letter include some of the largest global news organisations and internet companies including Google, Forbes, News Corp, Thomson Reuters, the New York Times, Bloomberg News, Guardian News and Media, the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers and Conde Nast; prominent European media companies and associations including the European Newspaper Publishers’ Association, Sanoma Media Netherlands B.V. and the European Publishers Council; national media outlets and journalists associations from across the continent; and advocacy groups including Index on Censorship, Greenpeace, the Center for Democracy and Technology and ARTICLE 19.

We understand that the applicant in the above-referenced case has requested that the chamber judgment of 10 October 2013 be referred to the Grand Chamber of the Court for reconsideration. We are writing to endorse Delfi’s request for a referral due to our shared concern that the chamber judgment, if it stands, would have serious adverse repercussions for freedom of expression and democratic openness in the digital era. In terms of Article 43 (2) of the Convention, we believe that liability for user-generated content on the Internet constitutes both a serious question affecting the interpretation or application of Article 10 of the Convention in the online environment and a serious issue of general importance.

The case involves the liability of an online news portal for third-party defamatory comments posted by readers on the portal’s website, below a news item. A unanimous chamber of the First Section found no violation of Article 10, even though the news piece itself was found to be balanced and contained no offensive language. The portal acted quickly to remove the defamatory comments as soon as it received a complaint from the affected person, the manager of a large private company.

We find the chamber’s arguments and conclusions deeply problematic for the following reasons.

First, the chamber judgment failed to clarify and address the nature of the duty imposed on websites carrying user-generated content: what are they to do to avoid civil and potentially criminal liability in such cases? The inevitable implication of the chamber ruling is that it is consistent with Article 10 to impose some form of strict liability on online publications for all third-party content they may carry. This would translate, in effect, into a duty to prevent the posting, for any period of time, of any user-generated content that may be defamatory.

Such a duty would place a very significant burden on most online news and comment operations – from major commercial outlets to small local newspapers, NGO websites and individual bloggers – and would be bound to produce significant censoring, or even complete elimination, of user comments to steer clear of legal trouble. The Delfi chamber appears not to have properly considered the implications for user comments, which on balance tend to enrich and democratize online debates, as part of the ‘public sphere’.

Such an approach is at odds with this Court’s recent jurisprudence, which has recognized that “[i]n light of its accessibility and its capacity to store and communicate vast amounts of information, the Internet plays an important role in enhancing the public’s access to news and facilitating the dissemination of information generally.”[1] Likewise, in Ahmet Yildirim v. Turkey, the Second Section of the Court emphasised that “the Internet has now become one of the principal means of exercising the right to freedom of expression and information, providing as it does essential tools for participation in activities and discussions concerning political issues and issues of general interest”.[2]

Secondly, the chamber ruling is inconsistent with Council of Europe standards as well as the letter and spirit of European Union law. In a widely cited 2003 Declaration, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe urged member states to adopt the following policy:

“In cases where … service providers … store content emanating from other parties, member states may hold them co-responsible if they do not act expeditiously to remove or disable access to information or services as soon as they become aware … of their illegal nature.

When defining under national law the obligations of service providers as set out in the previous paragraph, due care must be taken to respect the freedom of expression of those who made the information available in the first place, as well as the corresponding right of users to the information.”[3]

The same position was essentially adopted by the European Union through the Electronic Commerce Directive of 2000. Under the Directive, member states cannot impose on intermediaries a general duty to monitor the legality of third-party communications; they can only be held liable if they fail to act “expeditiously” upon obtaining “actual knowledge” of any illegality. This approach is considered a crucial guarantee for freedom of expression since it tends to promote self-regulation, minimizes the need for private censorship, and prevents overbroad monitoring and filtering of user content that tends to have a chilling effect on online public debate.

Thirdly, it follows from the above that the Delfi chamber did not thoroughly assess whether the decisions of the Estonian authorities were “prescribed by law” within the meaning of Article 10 § 2. Under the E-Commerce Directive and relevant judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), it was not unreasonable for Delfi to believe that it would be protected by the “safe harbour” provisions of EU law in circumstances such as those of the current case.[4] The chamber ruling sets the Court on a potential course of collision with the case law of the CJEU and may also give rise to a conflict under Article 53 of the Convention.

Finally, the chamber ruling is also at odds with emerging practice in the member states, which are seeking innovative solutions to the unique complexities of the Internet. In the UK, for example, the new defamation reforms for England and Wales contain a number of regulations applicable specifically to defamation through the Internet, including with respect to anonymous third-party comments. Simply applying traditional rules of editorial responsibility is not the answer to the new challenges of the digital era. For similar reasons, related among others to the application of binding EU law, a recent Northern Ireland High Court judgment expressly chose not to follow the Delfi chamber ruling.[5]

For all these reasons, we strongly urge the Court to accept the applicant’s request for a referral that would allow the Grand Chamber to reconsider these issues, taking into account the points raised by the signatories in this letter. There is no question in our minds that the current case raises “a serious question affecting the interpretation” of Article 10 of the Convention as well as “a serious issue of general importance” (Art. 43).

Sincerely,

Algemene Vereniging van Beroepsjournalisten in België

American Society of News Editors

ARTICLE 19

Association of American Publishers, Inc

Association of European Journalists

Bloomberg

bvba Les Journaux Francophones Belges

Center for Democracy and Technology

Conde Nast International Ltd.

Daily Beast Company, LLC

Digital First Media, LLC

Digital Media Law Project, Berkman Center for Internet & Society – Harvard University

Digital Rights Ireland

Dow Jones

Electronic Frontier Finland

Estonian Newspapers Assocation (Eesti Ajalehtede Liit)

EURALO (ICANN’s European At-Large Organization)

European Digital Rights (EDRi)

European Information Society Institute (EISi)

European Magazine Media Association

European Media Platform

European Newspaper Publishers’ Association (ENPA)

European Publishers Council

Federatie van periodieke pers, the Ppress

Forbes

Global Voices Advocacy

Google, Inc.

Greenpeace

Guardian News & Media Limited

Human Rights Center, Ghent University

Hungarian Civil Liberties Union

iMinds-KU Leuven, Interdisciplinary Centre for Law and ICT

Index on Censorship

International Press Institute

Internet Democracy Project

La Quadrature du Net

Lithuanian Online Media Association

Mass Media Defence Center

Media Foundation Leipzig

Media Law Resource Center

Media Legal Defence Initiative

National Press Photographers Association

National Public Radio

Nederlands Genootschap van Hoofdredacteuren

Nederlands Uitgeversverbond (NUV)

Nederlandse Vereniging van Journalisten

Net Users’ Rights Protection Association

News Corp.

Newspaper Association of America

North Jersey Media Group, Inc

NRC Handelsblad

Online News Association

Open Media Coalition – Italy

Open Rights Group

Panoptykon

PEN International

PEN-Vlaanderen

Persvrijheidsfonds

Raad voor de Journalistiek

Radio Television Digital News Association

Raycom Media, Inc.

Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press

Sanoma Media Netherlands B.V.

Telegraaf Media Groep NV

The New York Times Company

Thomson Reuters

Vlaamse Nieuwsmedia

Vlaamse Vereniging van Journalisten

Vrijschrift

World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers

[1] Times Newspapers Ltd v. the United Kingdom (Nos. 1 and 2), Judgment of 10 March 2009, para. 27. See also Editorial Board of Pravoye Delo and Shtekel v. Ukraine, Judgment of 5 May 2011.

[2] Judgment of 18 December 2012, para. 54.

[3] Declaration on freedom of communication on the Internet, 28 May 2003, adopted at the 840th meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies.

[4] The CJEU has ruled, with reference inter alia to Article 10 ECHR, that an Internet service provider cannot be required to install a system filtering (scanning) all electronic communication passing through its services as this would amount to a preventive measure and a disproportionate interference with its users’ freedom of expression and information. See Scarlet v. Sabam, Case C-70/10, Judgment of 24 November 2011; and Netlog v. Sabam, Case C-360/10, Judgment of 16 February 2012.

[5] J19 & Anor v Facebook Ireland [2013] NIQB 113 (15 November 2013), at http://www.bailii.org/nie/cases/NIHC/QB/2013/113.html.

14 Jan 2014 | News and features, Russia

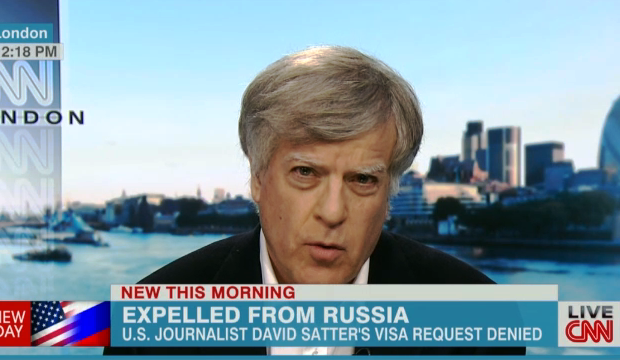

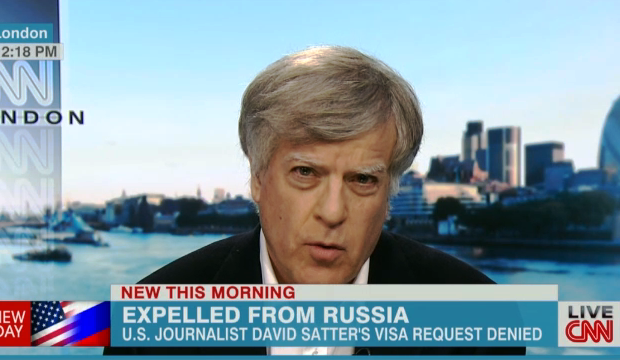

Fielding calls in the back of a London black cab, American journalist David Satter is a busy man.

Satter, who has reported on Soviet and Russian affairs for nearly four decades, was appointed an adviser to US government-funded Radio Liberty in May 2013. In September, he moved to Moscow. But at Christmas, he was informed he was no longer welcome in the country — the first time this has happened to an American reporter since the cold war.

Since Monday night, when the news of his expulsion from Russia broke, he’s been talking pretty much non stop, attempting to explain the manoeuvres which led to him being exiled from his Moscow home.

A statement issued by the Russian foreign ministry claims that Satter had violated Russian law by entering the country on 21 November, but not applying for a visa until 26 November.

Satter dismisses this as “nonsense”, saying he had been assured that a visa that had expired on 21 November would be renewed the following day, with no gap. As it happened, the visa was not renewed on time, “in order to create a pretext”, he tells Index.

To cut a short cut through a labyrinthine tale of bureaucracy: Satter says he left Russia in order to gain a new entry visa, which he could then exchange for a residency visa as an accredited correspondent for Radio Liberty.

He was repeatedly told this visa had been secured. Eventually, on 25 December, he was told that he had a number for a visa, but not the necessary invitation to accompany it. “Kafkaesque”, he calls it. The embassy official had never heard of this happening before. And, as Satter points out, he would not have been issued a number for a new visa in December if it had not been approved.

Eventually, he was told to speak to an official named as Alexei Gruby, who told him that “the competent organs” (code, Satter says, for the FSB) had decided that his presence in Russia was not desirable, language normally reserved for spies. “And now we see I have been barred for five years.”

“The point is, I urge you not to get caught up in their bureaucratic intrigues…the real reason was given to me, in Kiev, on 25 December.”

Is this just another example of FSB muscle flexing?

“Possibly. I’ve known them for a number of years, and I can’t always understand what they’re doing. Usually what they do is not very good…”

This is not Satter’s first brush with the Russian secret services. In a long career with the Financial Times, Radio Liberty and other outlets, he has experience of the KGB and its sucessor. “In 1979, they tried to expel me, accusing me of hooliganism. They once organised a provocation in one of the Baltic republics in which they posed as dissidents. I spent a couple of days with them, thinking I was with dissidents – I was really with the KGB. It’s a long history. It’s in my movie. We showed it in the Maidan [December’s anti-government protests in Ukraine]. Maybe they didn’t like that.”

Satter’s film, the Age of Delirium, is an account of the fall of the Soviet Union.

Is this expulsion a personal thing? Or a move against Radio Liberty? “It’s hard to say whether it’s me, or Radio Liberty, or both.”

Satter is concerned at leaving behind research materials and belongings in Moscow, saying it is likely his son, a London-based journalist, will have to go to Russia to collect them “unless they reverse their decision, which I hope they do”.

In spite of the recent amnesty that saw Pussy Riot’s Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina released from prison, as well as opposition figure Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the diagnosis for free speech in Russia is not good. Alyokhina dismissed her release as a “hoax”, designed to prove Putin’s power. Meanwhile, state broadcaster RIA Novosti has been dissolved and reimagined as “Rossia Segodnya” (“Russia Today” – no coincidence it bears the same name as the notorious English language propaganda station), with many fearing closer Kremlin control.

One Russian journalist I spoke to felt that, ahead of the Sochi games, the expulsion of Satter is a message to all journalists: no matter how experienced, well-known, and well-supported you are, you are still at the mercy of the authorities.

This article was posted on 14 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

14 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, France, News and features

What happened last Friday was unprecedented. Four days before the third major press conference of François Hollande’s presidency, the French version of celebrity magazine Closer published seven pages alleging that the president was having an affair with Julie Gayet, a 41-year old actress. Speaking to the AFP in a personal – and non presidential – capacity on Friday, Hollande described the publication as an “attack on the right to privacy” but did not deny the allegation. On Sunday, the spokeperson of his partner, Valérie Trierweiler, announced she had been admitted to a hospital due to stress prompted by the publication and that she would leave the hospital on Monday.

For the president to have a mistress would not seem surprising in a country with a long history of presidential mistresses and most French people are likely to remain unfazed. According to a poll commissioned by Le Journal du dimanche, 77% of French people feel that the alleged relationship between Hollande and Gayet does not concern them and don’t feel shocked by the allegation. What is new is the way in which Closer has intruded on the president’s private life.

Traditionally, French presidents’ affairs go unreported. François Miterrand’s double life and the fact that he had a daughter with his long-term mistress was only revealed at the end of his presidency and when his daughter was 20, in 1994, by Paris Match. At the time, the magazine had sought the president’s approval before publication.

Of course, things have changed. Nicolas Sarkozy is known to have blurred the lines between his public and private life, orchestrating the media coverage of his relationship with ex model Carla Bruni, whom he married during his presidential term. In 2011, the Dominique Strauss-Kahn scandal triggered a debate in the French media: had the French press been overprotective of the private life of one of its politicians, failing to report on DSK’s alleged track record of violence against women?

France’s strict privacy laws make it a criminal offence to publish information about someone’s private life without their consent. In 2012, the magazine was sentenced for publishing stolen photos of a topless Kate Middleton sunbathing with Prince Williams. The magazine had to take down the photos from their website and to return them to the couple. Following a complaint by Gayet’s lawyer, Closer has already taken down the allegations of a relationship between the actress and the president from their website. But, as happened with the breasts of the Duchess, the damage is done, and the allegations of an affair between Hollande and Gayet are now everywhere.

Gayet gate: a public affair?

As Closer’s allegations become public, France’s main news publications have started to report on the claims and what seemed to be only a private matter has started to seem much more interesting.

The allegations of a presidential affair raise the question of the status of Hollande’s current official girlfriend Valérie Trierweiler, a former political journalist, who has an office at the presidential palace, employs five people and accompanies the president on official occasions and trips abroad. France, unlike the United States, has no defined role for a “first lady” and the wives or partners of successive French presidents have occupied a blurry zone between the private and the public sphere. A certain confusion has presided over Trierweiler’s involvement in Hollande’s presidency. In June 2012 she committed a gaffe by tweeting her support for a rival to Ségolène Royal, Hollande’s former partner with whom he has four children. Closer’s allegations are likely to force Hollande to clarify the status of his relationship with Trierweiler, a personal matter, which also takes a public dimension.

Lastly, an interesting line of investigation has been opened by the online magazine Mediapart which claimed that the flat used for the alleged encounter of Gayet and Hollande is under the name of Michel Ferracci, suspected to have ties with the infamous Corsican Gang de la Brise de Mer, and his ex wife, an actress and a friend of Gayet. Hollande is believed to have come to the flat regularly, followed by police officers acting as bodyguards, which raises questions for his personal security.

This article was posted on 14 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

14 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the EU shifted its neighbourhood policy in the southern neighbourhood. In response to the revolutions and social movements in the region, the EU shifted the focus of its neighbourhood policy from economic development towards human rights. On 8 May 2011, the EU High Representative and the European Commission issued a joint communication proposing “A partnership for democracy and shared prosperity with the southern Mediterranean“.

The EU now emphasises the “three Ms”: money, market access and mobility, with the first “M” addressing the EU’s commitment to financially support transition to democracy and civil society. The strategy also heralded the creation of the Civil Society Facility for the neighbourhood (covering both the southern and eastern neighbourhoods), with an overall budget of €26.4 million for 2011 to strengthen civil society. In parallel, the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR) deployed a number of operations in the region to protect and promote freedom of expression, often without the consent of the host country.

The apparent efforts to promote freedom of expression in the southern neighbourhood after the Arab Spring are in stark contrast to the multilateral partnerships that the EU actually established, often with the now overthrown dictatorships. The Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (EUROMED), also known as the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) and formerly known as the Barcelona Process, was re-launched in 2008 as a multilateral partnership between the EU member states and 15 Mediterranean partner countries in the EU’s southern neighbourhood. Of the UfM’s six key initiatives launched prior to the Arab Spring, none related to the promotion of human rights. EU member states that border the Mediterranean Sea, in particular Italy, Spain and France, emphasised cooperation on migration, energy supplies and help with counter-terrorism, while adopting a relatively passive approach toward democracy and human rights.

Critics contend the UfM was overly concerned with regional security and economic partnership at the expense of human rights, including the right to freedom of expression. For example, in spring 2010, the EU began negotiations with Tunisia on advanced status within the European Neighbourhood Policy, with clear economic benefits for the country, even though, at the same time, the Ben Ali regime was clamping down on freedom of expression. Ben Ali’s government even introduced a draconian NGO law during the period of the advanced status talks, in an attempt to prevent Tunisian activists from lobbying the EU to be tougher on human rights issues. As a result, even with the new “three Ms” strategy, the EU and its member states suffer from a legacy credibility problem in the region and are often seen as former allies of repressive regimes.

The EU has continued to lack unity on the use of conditionality to enhance political and human rights reform. Germany, Finland and the Netherlands have generally been more supportive of this reform, whereas Italy and Portugal are less keen on penalising countries for failing to introduce reform. According to a survey of over 700 experts initiated by the European Commission, both the UfM and the EU have failed to deliver the expectations of key regional actors, 93% of those interviewed called on the EU to have a greater role in the region. The survey indicated that Turkey was perceived as the most active country in the region on the promotion of human rights, ahead of the US, followed by all EU countries combined.

In its near neighbourhood, the EU has had mixed levels of success in promoting freedom of expression. Enlargement continues to be the most effective tool at the EU’s disposal in incentivising countries to improve their domestic situation for freedom of expression. With enlargement slowing, this leverage may diminish and other levels have become important. Therefore, it is arguable that the Eastern Partnership and southern neighbourhood policy are test cases for how effective the EU can be beyond enlargement. Yet, with key regional actors in both the eastern and southern neighbourhoods all too aware of the EU’s failings, and with expectations high as to what the EU can achieve, ensuring these policies are strategic and sustained in their demands for freedom of expression is essential.