28 Nov 2014 | Academic Freedom, News and features, United States

Independent student newspapers struggle in an increasingly digital world. Advertising revenue is shrinking. Budding journalists must learn how to fill the gap while maintaining news coverage free of administration censorship.

Of the more than 500 student newspapers in the US, Index spoke with two papers about their work and how they finance themselves independently.

“We really value our independent status because it allows us to be critical of the administration and be a watchdog of our university,” Kyle Plantz, editor-in-chief at Boston University’s Daily Free Press, said in an email interview.

The paper formed in 1970 after the university’s then president John Silber cut funding to two campus publications to prevent coverage of Kent State protests. As a result they merged to become the Free Press.

In recent years, Daily Free Press staff has written articles covering topics on campus such as gender neutral housing and students’ issues with the Student Activities Office, which oversees student organisations. In late 2011-2012, the paper provided extensive coverage of the arrest of two ice hockey players charged with sexual assault.

Nicole Brown, editor-in-chief at New York University’s Washington Square Press, also said her paper acts as a watchdog on the NYU administration.

“We need to be able to question our university and present information to the community,” Brown said. “We also need to be able to voice our opinions without fear of being punished for those opinions.”

The Washington Square Press keeps an open dialogue on campus through its feature, NYU Reacts. It includes students’ thoughts on topics ranging from ISIS subway threats to pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. The paper also publishes articles on sensitive issues, such as a November 2013 piece in which NYU faculty express concern over the London campus’s rapid expansion.

Many student papers struggle to maintain steady revenue. Brown said the Washington Square Press relies on advertising, sold and managed by student staff.

“With a move toward more online content, there are more opportunities to sell ad spaces online, as well as in print,” Brown said.

For the Free Press, nearly $70,000 (£44,576.05) debt to their printers recently threatened to shutter their publication. They switched from publishing four days a week to once a week and, on 10 November, launched a crowd-sourcing campaign.

The paper surpassed their goal and raised over $82,000 in just three days, with Daily Free Press alumnus Bill O’Reilly donating $10,000 and local businessman Ernie Boch Jr. donating $50,000.

“[Reducing publication], along with cutting some other costs, we are able to continue to receive ad revenue and sustain our weekly print edition,” Plantz said. “We are assessing how we want to use [the extra funds] and what will be beneficial to our organization in the future.”

Independent newspapers must find a way to financially sustain themselves or campuses will lose reliable, student-run news.

As Plantz said, “We are one of the only outlets that allow students to have a voice, question authority, and be a place for students, faculty, staff, and the administration to come together to learn about what’s happening on campus.”

This article was originally posted 28 November on indexoncensorship.org

27 Nov 2014 | Americas, Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, Ireland, News and features, United Kingdom, United States

How did people organise protests before the internet? How did riots happen? How did terrorists carry out attacks? All these things definitely happened. I remember them distinctly. In the days before the world wide web, all sorts of things occurred without anyone “taking to social media” or “using sophisticated communications technology” (phones).

But current discussions are premised on the idea that the web in itself has created civil disorder and even terrorism.

In Ireland, as protests have got to the point where government ministers can barely leave the house without being confronted by citizens unhappy with proposed household water metering, commentator Chris Johns suggested that “Social media has brought more illness to Ireland than Ebola has. Anarchists, extremists and all-round loonies can find a voice and organisational structure – if only for a decent riot – amidst a political fragmentation that rewards those who shout the loudest.”

Considering there have been no recorded incidents of Ebola in Ireland, the first part of this assertion could be technically true; or we could say that social media has brought the same amount of illness to Ireland — none. As for the anarchists and loonies, well, they have always been with us, and had some success in organising before Facebook came along.

Across the Atlantic, St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCulloch said that “nonstop rumours on social media” had significantly hampered the investigation into the killing of Michael Brown, and contributed to his decision not to prosecute. This in the land of the First Amendment, where the justice system long ago learned to deal with hearsay.

Back over the ocean again, the UK’s Intelligence and Security Committee report into the murder of Drummer Lee Rigby by Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale pointed to a Facebook message sent by Adebowale, in which he expressed a desire to kill a soldier. In spite of several failures by the intelligence services, who were long aware of Adebowale’s tendencies, Facebook faced criticism for not “flagging up” the message to the security forces. Social media to blame once again.

Why do we do this? Why must every single occurrence now have a social media angle?

Partly because everything many of us do now does have an internet angle. The web is simply part of human interaction for millions.

But for some it seems foreign. My generation is the last that will remember life before the internet.

For all that, it is still shockingly new. I’m not just saying that to make myself feel younger. Some people my age and older (“digital immigrants”, apparently, which makes me a double immigrant) have adapted reasonably well to our new environment. Some really haven’t. I have watched a QC attempt to explain the difference between a reply and a direct message on Twitter. It was as you’d expect, equal parts cute and infuriating, but it did also make one think how insanely fast we have adapted to certain technologies, and how some people are left behind.

When was the last time they changed Facebook? I honestly couldn’t say. But remember when complaining about changes to Facebook was a thing? We used to object; now we install our own mental updates and carry on, using new features and forgetting what went before. I have literally no idea what Facebook looked like when I joined it. Or Twitter for that matter.

And I, remember, am an immigrant, not a native. There are still a lot of people who don’t want to emigrate to the web, because they think it’s full of conspiracy theories and pornography. And there are some who occasionally “log on” to the internet, and then “log off” again, like an overnight work trip to Leicester.

So when something happens that involves an email, a tweet, a Facebook update or whatever, for some that is still of interest in itself.

Will this ever end? Hopefully. As time goes on, the distinction between the internet and THE INTERNET will become clearer. THE INTERNET is a culture; the place where the likes of Doge and Grumpycat come from, and all their predecessors (I still have a soft spot for Mahir “I Kiss You” Çağrı. Look it up, youngsters). The internet is simply a communications tool, like millions upon millions of tin cans joined with taut string. When we can get this a little clearer in our heads, then finding a web angle for every occasion will feel a bit silly, like blaming Bic for poison pen letters.

That is not to say that we should take the web for granted, or become blase about its use and abuse. But we must treat it as simply a part of the environment. Essentially, we have to stop thinking about things happening “on the internet”. There is no “internet freedom” — there is just freedom. There is no “internet privacy” — there is privacy. There are no “internet bullies” — there are bullies.

Put simply, we need to ban the word “internet”.

This article was published on 27 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Nov 2014 | Cyprus, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

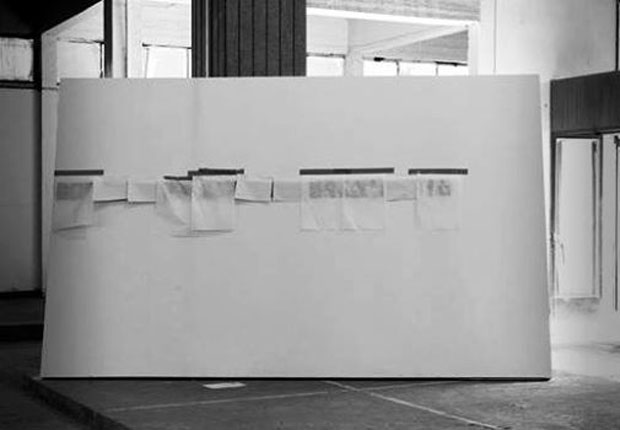

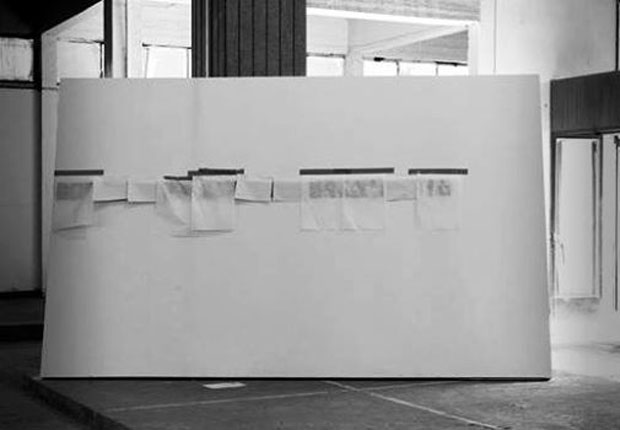

The empty walls following the confiscation of Paola Revenioti’s work (Photo: Accept)

Gay rights NGO Accept-Cyprus LGBT has slammed police censorship, after photographs of the Greek trans activist Paola Revenioti were confiscated and its chairman charged with exhibiting obscene material in a public space. Revenioti’s photo exhibition “Diorthosi” (Correction) was staged at Nicosia Municipal Market to mark Transgender Day on 20 November.

“This incident, unfortunately, was not something that surprised me. Censorship of art still exists in our so-called ‘democratic’ society,” Revenioti told Index on Censorship.

“Although this confiscation brought the issue of censorship to the forefront, which is a good thing, it overshadowed the essence of the exhibition, kept people away from the project. This is scandalous. Art is the way every one communicates his own truth. And with this action, they have vulgarised my own truth,” she stressed.

The exhibition, part of a series of events organised the NGO, was seized following a complaint by a citizen who disagreed with the content of the photographs which depicts life through the lens of Revenioti. Police acted without informing the municipality of Nicosia, which had licensed the space of the market for this exhibition, or the organisers, Accept said.

Costa Gavrielides, president of Accept, was questioned and officially charged with “publication of lewd content” in public space. Some of the photos eventually were returned, and others that depict male nudity were withheld as evidence for the subsequent trial.

The NGO filed an official complaint regarding the incident to the national anti-discrimination body, the Office of the Ombudsperson, and will further make a formal complaint to the local authorities as well as the European Parliament and the European Commission.

The Nicosia Municipal Arts Centre condemned the action as an “overt form of censorship” that affects the artistic community of Cyprus.

“The police acted in a legal way,” was the response from police spokesperson Andreas Angelides.

This article was published on 26 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org