25 Apr 14 | Americas, News and features, United States, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Image: Bplanet/Shutterstock)

(a list poem)

Because if you’re an artist, you never know where you’ll go.

Because you need a personal identity number to send a package.

Because an IP address is not a perfect proxy for someone’s physical location, but it is close.

Because I do most of my research online.

Because there hasn’t been a proper rain in California in over three years, and this year may be the driest in the last half millenium.

Because the burning of fossil fuels is destroying our atmosphere.

Because persistent cookies are stored on the hard drive of a computer until they are manually deleted or until they expire, which can take months or years.

Because tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term records of individuals’ browsing histories.

Because server farms require massive amounts of energy.

Because the friend who wanted to send the email “Photos from Taksim Square” couldn’t until she changed the subject to “Paris Vacation Photos”.

Because the line between “public” and “private” is tenuous at best.

Because the ACLU is doing its best.

Because a webcam’s images might be intercepted without a user’s consent.

Because a surveillance program code named “Optic Nerve” was revealed to have compiled and stored still images from Yahoo webcam chats in bulk in Great Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters’ databases with help from the United States’ National Security Agency, and to be using them for experiments in automated facial recognition.

Because it’s sketchy to be a Communist.

Because the Defending Dissent Foundation is all kinds of busy.

Because the U.S. army actively targeted nonviolent antiwar protestors in Washington in 2007.

Because I saw it on Dronstagram.

Because everything will or might end up on the internet.

Because the internet is a wormhole full of parasites.

Because I am trying to connect all of the dots.

Because free speech is a tinted mirror.

Because all mediated information is processed, edited, and altered.

Because Wally Shawn had to bring his play to Glenn Greenwald since the journalist who broke the story about Edward Snowden can’t return to the United States.

Because the author risked his freedom and physical security for the truth.

Because artistic solidarity is framed as criminal complicity.

Because how could I forget that language is always political?

Because Chelsea Manning is still being misgendered.

Because the personal is always political.

Because it’s not just the major political players.

Because of the metadata collection.

Because a local surveillance hub may start out combining video camera feeds with data from license plate readers, but once you have the platform running, police departments could plug in new features, such as social media scanners.

Because the Domain Awareness Center’s focus has been not on violent crime, but on political protests.

Because the collapse of the economy and the devastation of the environment are two sides of the same coin.

Because of the NSA’s presence at UN climate talks.

Because of the vested interests in the oil industry.

Because tell me something I don’t know.

Because my personal information is probably being used not just for advertising purposes.

Because despite Facebook’s rights and permissions policies, I still want to share with my friends.

Because Pussy Riot was imprisoned.

Because the Trans-Pacific Partnership would rewrite rules on intellectual property enforcement, giving corporations the right to sue national governments if they passed any law, regulation, or court ruling interfering with a corporation’s expected future profits.

Because I don’t know who is making money off of my information.

Because Abstract Expressionism was funded by the CIA.

Because of the time-honored tradition of governments keeping tabs on artists.

Because we don’t want jobs, we want to live.

This poem was posted on April 25, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Apr 14 | Academic Freedom, News and features, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

In February, students defied a protest ban imposed by the University of London to speak out against the privatisation of university support services. (Photo: Peter Marshall/Demotix)

There is a strong attitude across university campuses that censorship is a good tool for the benefit of a multicultural and inclusive society, that respects the values of all its members, freeing them from being exposed to anything they may find “harmful”.

Many students now sign up to policies that promote “safe space” throughout the university campus from the clubs and bars, to the seminar room and lecture theatres. Most of the time these policies go unnoticed and unchallenged as the bureaucrats strengthen their grip over the university and its members, and political activity wains under prevailing conformity and debateophobia.

These policies exist in antithesis to the true purpose of institutions of higher learning – to debate every idea and challenge every prejudice.

The promotion of safe spaces has been the preserve of National Union of Students (NUS) officials and university management for a number of years, seeking to create inclusive and welcoming environment for a growing student body, and attract more students from minority and/or vulnerable backgrounds. Originally the policy specifically dealt with the LGBT community. The US group Advocates for Youth describe safe space as one in which every individual can “relax and be fully self-expressed” free from feeling uncomfortable, unwelcome or unsafe.

The University of Bristol Students’ Union expresses the policy aptly: “The principle values [adopted from the NUS’ ‘safe space’ policy] are to ensure an accessible environment in which every student feels comfortable, safe and able to get involved in all aspects of the organisation free from intimidation or judgement” (my emphasis); ranging from freedom from physical and criminal activity, to being free from having one’s culture and beliefs questioned.

In the November of last year the LGBT society at the University of Liverpool lodged a complaint against the Islamic Society’s (ISoc) hosting of Cleric Mufti Ismail Menk due to his homophobic views, appealing to the Liverpool Guild of Students safe space policy. Despite the meeting being private and only open the ISoc members, the LGBT believed that the events would impinge on their “freedoms and happiness”, and would rather the Liverpool Guild of Students ban the event than have their lifestyles judged by others.

Even university institutions themselves have codified what free speech should look like on campus. The London School of Economics requires speakers to be screened. Bolton University details topics considered to be outside of the realm of debate, because of their controversial or sensitive nature, from animal experimentation to sexual abuse of children and paedophilia, and, most worryingly, “where the subject matter might be considered to be of a blasphemous nature”.

Given that such august institutions have taken on the narrative of safety first, it is no surprise that this has only strengthened students as censors resolve.

Last month the student union at the University of Derby revealed that it would be continuing its ban on the UK Independence Party (UKIP) in an upcoming debate in the run up to the 22 May European and local council elections. This follows its refusal to allow David Gale, UKIP candidate in the Police and Crime Commissioner elections of 2012, to take part in a Q&A session. This censorship and conformism came under the tired old banner of ‘no platform’, with the SU contending that they had the right to create a space in which students feel safe while studying on campus.

The safety-first mentality also pervades throughout the on-going No More Page 3 and anti-lad culture campaigns that are swarming across campuses in the UK. Painting a regressive view of human beings the campaigns believe that a bad joke, a bit of over zealous flirting and seeing a pair of breasts irredeemably damage women who come into have to look at them and creates an “unrealistic and potentially damaging picture of what women’s bodies look like”.

Unsurprisingly, whether it’s No More Page 3 or the ban of Blurred Lines, any attempt to engage in open and critical discussion of the issues has been met with scorn. Lucy Pedrick, of Sheffield Students’ Union council, believes a “referendum [on the banning of the sale of The Sun newspaper on campus] would not be a fair debate”, keeping the discussions behind closed doors for those who are members of the right forums and councils.

It appears then that today’s students are too vulnerable to be exposed to any robust and challenging discussion. This grows out of a culture that has promoted the idea that every individual is emotionally vulnerable and cannot cope with a growing range of encounters and experiences. It is now believed that we live in a world of unmitigated risks and problems, only waiting around the corner to trip you up again, and our ability to deal with everyday problems seems to have diminished. According to sociologist Frank Furedi, vulnerability has become conceptualised a central component of the human condition and “contemporary culture unwittingly encourages people to feel traumatised and depressed by experiences hitherto regarded as routine”, from unwanted cat-calling to the discussion of dangerous ideas.

It’s a far cry from the tradition out of which the theory of liberal education and the modern university was born. The period of the Enlightenment was led by the rallying call of Immanuel Kant – ‘Sapere aude!’ – dare to know and dare to use your own understanding in the creation and formation of your own opinions. However, this is the reverse of what we are seeing today as debate is closed down and speech is censored on campus all in the name of safety.

If we are to recapture the campus, lead the progress of human knowledge, and create an active and engaged citizenry towards progressive social change, it’s free speech and expression we must engage in.

This article was posted on 25 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Apr 14 | Lebanon, News and features, Religion and Culture, Young Writers / Artists Programme

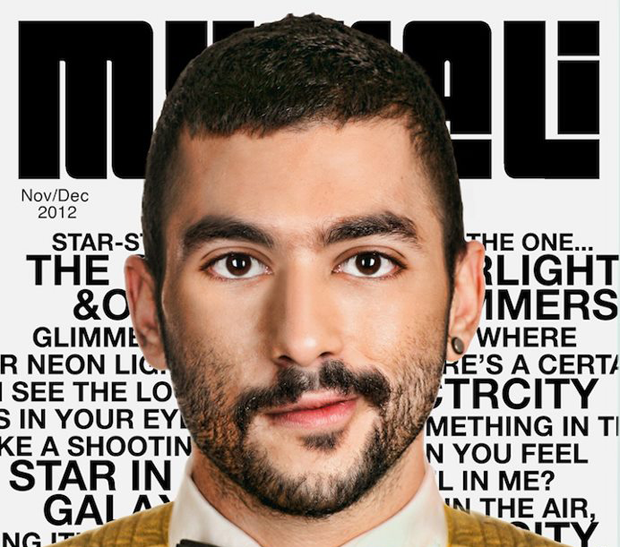

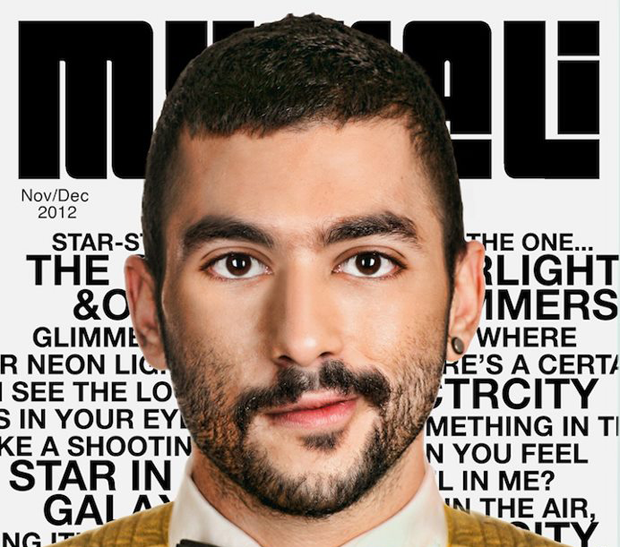

Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, is the lead singer of Mashrou’ Leila

While walking the streets of the upscale downtown district of Beirut, or sipping cocktails in one of El-Hamra’s bustling bars, one could easily forget that Lebanon is a country where civil liberties are still in debate.

Article 534 of the Lebanese penal code states: “Any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature is punished by imprisonment for up to one year.” The vaguely worded article has and is still being used to crackdown on the LGBT community in Lebanon. Compared to its neighbours in the Middle East, Lebanon has long been considered one of the least conservative countries in the region. According to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2013, 18% of the Lebanese population thinks that homosexuality should be accepted in the society, putting it way ahead of Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia where almost 97% of the population views homosexuality as deviant and unnatural.

The Lebanese Psychiatric Society issued a statement in early 2013 saying that: “The assumption that homosexuality is a result of disturbances in the family dynamic or unbalanced psychological development is based on wrong information” — making Lebanon the first Arab country to dismiss the belief that homosexuality is a mental disorder. On 28 January 2014, Judge Naji El Dahdah of Jdeideh Court in Beirut dismissed a claim against a transgender woman accused of having a same-sex relationship with a man, stating that a person’s gender should not simply be based on their personal status registry document, but also on their outward physical appearance and self-perception. The ruling relied on a 2009 landmark decision by Judge Mounir Suleimanfrom the Batroun Court that consenual relations can not be deemed unnatural. “Man is part of nature and is one of its elements, so it cannot be said that any one of his practices or any one of his behaviours goes against nature, even if it is criminal behaviour, because it is nature’s ruling,” stated Suleiman.

Despite the recent positives, being gay in Lebanon is still a taboo. In a country drenched in sectarianism, debates about homosexuality are easily dismissed in the name of religion and homosexuals are accused of promoting debauchery.

“People in Lebanon, and across the region, still act like homosexuality doesn’t exist in our society,” said Kareem, who requested that Index only use his first name. “I think it’s important that we start the conversation and get the issues out in the open, so people can start acknowledging it and then decide their stance on. The fight for our rights comes later on,” he added.

In 2013, Antoine Chakhtoura, mayor of the Beirut suburb of Dekwaneh, ordered security forces to raid and shut-down Ghost, a gay-friendly nightclub. “We fought battles and defended our land and honor, not to have people come here and engage in such practices in my municipality,” the mayor asserted.

Four people were arrested during the raid and brought back to municipal headquarters where they were subject to both physical and verbal harassment: forced to undress, enact intimate acts which included kissing, as well as being violently beaten. Marwan Cherbel, minister of interior at the time of the incident, backed the mayor’s actions, adding that: “Lebanon is opposed to homosexuality, and according to Lebanese law it is a criminal offence.”

Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. In a similar raid on a movie theatre in the municipality of Burj Hammoud known to cater for a gay clientele, 36 men were arrested and forced to undergo the now abolished anal probes — known as tests of shame. The raid came only a few months after Lebanese TV host Joe Maalouf dedicated an episode of his show Enta Horr (You’re Free) to exposing a porn cinema in Tripoli where it was claimed that young boys were being sexually abused by older men.

“The fact that these incidents received a lot of media coverage, some of which denounced the raids, is a sign that the public is little by little taking an interest in the issue of gay rights,” said Kareem. “Five or six years ago, this could have easily gone unnoticed. While the gay community might not be fully accepted or tolerated in Lebanon, it has been gaining a lot more visibility in recent years.”

Helem, a Beirut-based NGO, was established in 2004 to be the first organisation in the Middle East and Arab world to advocate for LGBT rights. In addition to campaigning for the repeal of Article 543, Helem offers a number of services, including legal and medical support to members of the LGBT community. Organisations like Helem and its offshoot Meem, a support group for lesbian women, had a huge impact on raising awareness and correcting misconceptions about homosexuality. Support from Lebanese public figures has also been on the rise in recent years. For example, popular TV host Paula Yacoubian and pop star Elissa have both shown support for the LGBT community in Lebanon via their Twitter accounts.

While the struggle to change the law continues, young artists have been challenging social norms through art. Mashrou’ Leila, a Beirut-based indie rock band, has sparked a lot of controversy thanks to their songs, in which they unapologetically sing about sex, politics, religion and homosexuality in Lebanon. In Shim el Yasmine, the band’s lead singer, Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, sings about an old love, a man whom he wanted to introduce to his family and be his housewife. Director and art critic, Roy Dib, recently won the Teddy Award for best short film in 2014 at the 64th Berlinale International Film Festival with his film Mondial 2010. The film tells the story of a gay Lebanese couple on the road to a holiday weekend in Ramallah, Palestine. It tries to explore the boundaries that make it impossible for a Lebanese person to go into Palestine, as well as the challenges faced by a homosexual couple in the region.

The battle for gay rights in Lebanon is multilayered, and while change is starting to feel tangible, there is still a lot to be done.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Apr 14 | Ireland, News and features, Politics and Society, Turkey, United Kingdom

Armenian protesters in Lyons accused Turkey of supporting Islamic rebels in an attack on Kessab, an Armenian majority town located in Syria, on the Turkish border. (Image: Benjamin Larderet/Demotix)

It is, as Zhou Enlai might have said, probably too early to tell how significant Tayyip Erdogan’s comments alluding to the Armenian genocide will be.

The Turkish prime minister seems to have broken one of his country’s great taboos. In a statement translated into nine languages, the AK leader said: “It is with this hope and belief that we wish that the Armenians who lost their lives in the context of the early 20th century rest in peace, and we convey our condolences to their grandchildren.”

“Having experienced events which had inhumane consequences — such as relocation — during the First World War, should not prevent Turks and Armenians from establishing compassion and mutually humane attitudes among towards [sic] one another.”

According to Anadolu, Turkey’s state news agency, Erdogan also commented: “In Turkey, expressing different opinions and thoughts freely on the events of 1915 is the requirement of a pluralistic society as well as of a culture of democracy and modernity.”

This is not, you will have noticed, an apology. Offering condolence is not at all the same as expressing remorse. Though some would say it is not Erdogan’s duty to express remorse; he is the prime minister of the modern republic of Turkey, not the Ottoman Empire under which the alleged slaughter of over 1.5 million Armenian Christians in 1915 took place.

And some are utterly contemptuous of Erdogan’s statement: Reuters quotes the Armenian National Committee of America describing the statement as an “escalation” of Turkey’s “denial of truth and obstruction of justice”.

But let us assume that a) Erdogan is in a position to speak for Turkey past as well as present, and b) there is, at the kernel of this, an attempt at reconciliation with Armenia and the Armenian diaspora.

The very mention of the events are significant against the backdrop of the Turkish Penal Code’s controversial Article 301, which forbids insulting “the Turkish nation”. That law has in the past, effectively barred discussion of the genocide, and created a environment where simply identifying as Armenian within Turkey was seen as a provocative act.

The most famous victim of this culture was Hrant Dink, the editor of Agos who was assassinated in January 2007.

Dink saw himself as Turkish-Armenian, and his newspaper was bilingual. He was a firm believer in the potential for dialogue in bringing some reconciliation between Turks and Armenians. He also believed such dialogue could only take place in an atmosphere free of censorship, to the extent that he vowed that he would be the first person to break a proposed French law making denial of the Armenian genocide a crime (a cheap political trick aimed at both currying favour with the Armenian community in France and creating a barrier for Turkey’s proposed entry into the EU).

Ultimately, Dink believed that progress could only be made if we were able to talk freely and access historical debate without impediment or fear.

History, like science, is a process rather than a dogma. And like science, one’s interpretations of history can vary based on both the evidence available and the prevailing mood.

For a long time after the creation of the Irish state, for example, the teaching of history in schools was simple. I recall one primary school history text which seemed to consist entirely of tales of the terrible things foreigners had done to the Irish: first the Vikings, then the Normans, and finally the English. The book finished pretty much where the 1919 War of Independence began. The last page featured the words of the national anthem and a picture of the national flag.

Sympathetic portrayals of English people, and British soldiers in particular, were thin on the ground — Frank O’Connor’s tragic short story Guests of the Nation being one of the very few.

Since the late 1990s peace process, both fictional and historical perspectives on Ireland’s relationship with Britain have changed. Some of the novels of Sebastian Barry, for example, attempt to tell stories of people who were neglected and even vilified in nationalist, Catholic, post-independence Ireland. Part of the plot of Paul Murray’s Skippy Dies has a Catholic school history teacher attempting to get his pupils interested in Irish soldiers who fought for Britain in World War I. Meanwhile, a recent book by nationalist historian Tim Pat Coogan, attempting to paint the Irish potato famine as deliberate genocide rather than cruel neglect, was given short shrift, in spite of the fact that this would have been a mainstream view until relatively recently — one must only listen to the sickly sentimental lyrics of rugby anthem The Fields of Athenry, penned in the 1970s, to understand the appeal of that victim status to the Irish imagination. Wrongs were certainly done in Ireland, but the relationship between the two nations was a hell of a lot more complex than the oppressor/oppressed line that was spun for so many years.

There was no official sanction on differing views of Anglo-Irish relations, but politics permeated the debate. Likewise with the recent intervention of British education secretary Michael Gove on the issue of how World War I is taught in schools. Gove claimed that the idea of a pointless war in which a moribund (figuratively) ruling class led moribund (literally) working class boys to their graves was a modern lefty invention. He was wrong, in that that view had been common even in the 1920s, but his opponents were equally adamant in their insistence that there could only be one view of World War I. None of this discussion was accompanied by new evidence on either side.

At the extreme end of this hyper-politicisation of history are the Holocaust denial laws of many European countries, and laws on glorification of the Soviet era in former Eastern bloc.

In his cult memoir Fuhrer-Ex, East German former neo-nazi Ingo Hasslebach described how, growing up in the DDR, with its overwhelming anti-fascist narrative, nazi posturing was the ultimate rebellion. In the modern era, France’s prohibition on nazi revisionism has led some young north African immigrants, alienated from the French nation state, to see anti-semitism and the quasi-nazi quenelle gesture as the ultimate “fuck you” to the authorities.

Taboos about discussing events of the past breed bad history and bad politics. For the sake of Turkey, and the rest of us, Erdogan should be held to his words on the necessity of free speaking and free thinking.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Apr 14 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

Mayada Ashraf

While Egypt’s hugely controversial Al-Jazeera trial has been grabbing international attention, the recent death of 22-year-old reporter Mayada Ashraf – allegedly at the hands of the police – appears to have left more of a lasting impact on Egyptian journalists working amid the ongoing violence.

On Tuesday, Al-Jazeera “Marriot Cell” defendants again appeared in court to face charges of complicity in terrorism and “spreading false news.” Journalists at the hearing were temporarily booted out, while the judge in the chaotic session admitted he could not understand several pieces of audio evidence aired during the trial. The case has cemented in many people’s minds around the world the idea that Egypt is now a place of kangaroo courts; a dire environment for press freedoms, home to repressive anachronisms that everyone who remembers Tahrir Square in 2011 may be forgiven for thinking were a thing of the past. They’re not.

On March 28 Ashraf, a reporter with Al-Dostour, was gunned down while covering clashes between Muslim Brotherhood supporters and police in Ain Shams, eastern Cairo. Videos showed her corpse being rushed to safety as blood poured over her face. She died soon after.

Ashraf became the fifth reporter to die while reporting on clashes in Egypt since June 30, according to Committee to Protect Journalists figures. And while it may have been a month ago, the death of a young female journalist (who purportedly wrote last August that “Morsi is not worth dying for but Sisi is also not worth renouncing our humanity for”) has had a lasting impact in Egypt.

Press freedom campaigners have been collecting testimonies and eyewitness accounts from the day Ashraf died, an attempt to establish what really happened beyond the claims of the security apparatus.

Forensics officials suggested the shooter was from the Brotherhood, offering a series of exacting distances, heights and perspectives on where the gunman was when Ashraf was hit. The gunman was a few metres away from Ashraf, and probably standing on a car or pavement when she died, claimed senior forensics physician Hisham Abdel Hamid. Interior Minister Mohamed Ibrahim defended the role of security forces that day.

However Journalists Against Torture, a group aiming to build solidarity and offer help among journalists, has spoken to two eyewitnesses who contradict the official account of that day.

“As a journalist, you usually rely on the first eyewitnesses,” explains Journalists Against Torture’s Ashraf Abbas, tucked away in a corner of a café in Cairo’s Boursa district. “And two eyewitnesses said [the shot] came from the security forces.” One of those eyewitnesses, another journalist, was close to Ashraf when the bullet hit her head.

Abbas believes these testimonies carry more weight. “For us, this is more credible than what the Interior Ministry says…They rush into lies before they’ve had time for a proper investigation.” Mohamed Ibrahim’s denial came just two days after Ashraf was shot.

The state’s response, often in the face of contrary evidence, has been used before to absolve itself of any possible blame from a string of controversial deaths.

In November, Cairo University engineering student Mohamed Reda was fatally shot with cartouche (birdshot) as police moved in on a campus protest. The Interior Ministry denied firing anything other than tear gas, before video evidence explicitly disproved that claim. The government then blamed “Brotherhood students” for Reda’s death.

Forensics and ministry officials subsequently claimed the police did not use–or even possess–the rounds which killed Reda. The shooter must have been a Brotherhood student, they argued.

Mohsen Bahnasy is a lawyer who contributed to the investigation into killings during the November 2011 Mohamed Mahmoud Street clashes, events now seen as a case study in disproportionate, lethal force by the Egyptian police. Bahnasy told Index in November that four-millimeter and 8.5-millimeter birdshot found at Mohamed Mahmoud has since appeared in the corpses of students (like Reda) killed in the post-July crackdown – deaths that have been blamed on the Brotherhood.

“Now they have something to hang all their problems on,” Abbas claims, referring to the Brotherhood bogeyman theory used by the authorities to write off deaths, terrorism and even a recent outbreak of tribal violence which left almost 30 dead in Aswan in southern Egypt.

“The killing of Mayada Ashraf was a real wake-up call for the journalistic community. And it has certainly raised serious concerns about how the journalistic community is taking action to protect its own people,” says Aidan White, director of the London-based Ethical Journalism Network.

Al-Dostour editor Essam Nawabi resigned in protest against the death of his colleague. Photojournalists have also launched a series of brief strikes and demonstrations to demand better conditions and protections. This growing anger amongst Egypt’s media community has often reached the doors of the Journalists’ Syndicate, long accused of not doing enough to protect journalists.

Journalists have claimed the police are deliberately targeting them. During clashes between students and police at Cairo University two weeks ago which left one student dead, two journalists were also seriously injured: Khaled Hussein was shot in the chest with live ammunition, while Amr Abdel-Fattah received birdshot wounds. Another photojournalist, Amru Salahuddien, claimed police “intentionally” targeted journalists inside the university: “I was hiding behind a palm which they kept firing at for at least one minute,” he tweeted shortly afterwards.

“A lot of the anger that we’ve seen among rank-and-file journalists in Egypt, particularly younger rank-and-file journalists, is being aimed not just at the authorities (for their failure to provide protection), but also the Journalists’ Syndicate,” White says.

The syndicate has since agreed to donate 100 bulletproof vests and helmets, and promises field reporters will be safe in the future. But are small acts of solidarity by journalists going to change things? “The momentum comes and goes,” Abbas admits, drawing parallels with the fierce debate over press freedoms after “Black Wednesday” in 2005, when mobs sexually assaulted female protesters and journalists during protests. “Now there is momentum again, but we can’t depend on this…we have to make solid gains, pass laws and build something solid.”

Until then, journalists in Egypt are still at risk. For some, Mayada Ashraf’s death is a case study in how the state responds to violence it is accused of carrying out with disregard and impunity. White argues the response could easily be different.

“Was this a killing by groups supportive of the Muslim Brotherhood, or were these thugs working for the police?” he asks. “The only way to find that out is to have a proper investigation. That is what is required.”

Additional reporting by Abdalla Kamal

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorhip.org

24 Apr 14 | India, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

“Gas Wars — Crony Capitalism and the Ambanis” is journalists Paranjay Guha Thakurta, Subir Ghosh and Jyotirmoy Chaudhuri’s collaborative effort exposing one of India’s biggest business conglomerates’ murky dealings with the government.

The authors detail how a hydrocarbon production sharing contract in Krishna Godavari, off the Bay of Bengal, in Andhra Pradesh, was allegedly rigged to benefit Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) headed by Mukesh Ambani, at significant cost to the public exchequer. The book contends that high ranking government officials, including ministers, aided and abetted the pillage of public resources.

A fire-and-brimstone attorney’s notice from RIL arrived the day after the book was launched. It had quite an eerie feel to it. The notice started with a disclaimer about the Reliance groups’ highest regards for constitutional rights including freedom of expression, and then accused the authors of a deep-rooted conspiracy to malign the company’s reputation. It took strong exception to the book’s title and went on to allege that the contents are nothing but malicious canards. Nothing sort of an unconditional public apology would mitigate the harm caused, failing which, criminal and civil proceedings would be unleashed. Drawing lessons from the Wendy Doniger episode, the notice threw out a wide net. It included not only Authors Upfront and FEEl Books Private Ltd, the e-book publisher and distributors, but also “electronic distributors” like Flipkart and Amazon.in. Even the Foundation for Media Professionals, a non-governmental organisation which forwarded e-invites for the launch event, was not spared. A second notice in the same vein, this time from RNRL, followed soon after.

Why does the book roil the Ambanis? In an interview, Guha Thakurta, one of the authors, revealed that the book delves into how both the central and the Gujarat governments worked hand-in-glove with the Reliance companies in structuring the deal. In effect, the government kowtowed to the companies’ diktats, the authors assert. It went out on a limb to hike the price of gas, and was stopped in its tracks by the Election Commission.

Moreover, it has become a hot-button political issue since the Aam Aadmi Party, which is contesting the elections on an anti-corruption plank, has left no stone unturned to relentlessly question the Ambanis and Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi, who is running for prime minister. The questions have so unsettled the Reliance companies that they have taken to an “Izzat (honour) campaign” and SMS blitz to convince Indians of its innocence. Further, the companies claim in court that they are victims of a “honey trap”- apparently the government isn’t the custodian of the country’s natural resources and had lured them with false promises.

Guha Thakurta maintains that he has acted in the finest traditions of fairness and journalistic integrity. Senior officials of the companies have been interviewed, their views, refutations and assertions–everything has been presented. But his travails in publishing the book provide cause for consternation. Self-publication was the sole option, if one goes by Bloomsbury India‘s craven surrender. For the record, not only did it withdraw a book which would have exposed how India’s national airline was bled dry, but went ahead and apologised to the minister who threatened to sue for libel. A leading national publisher had been approached, and a deal had been worked out, but Guha Thakurta decided to go solo when substantial changes were demanded.

For Reliance, intimidating anyone who isn’t writing hagiographies of Dhirubhai Ambani–the company’s founder–is par for the course; one is a worse offender for even whispering anything against their cavorting with officials in the top echelons of government. And their modus operandi of silencing criticism reveals the extent of crony capitalism.

In its May 2013 issue, Caravan magazine published a cover story on India’s Attorney General. It bared details about how his opinions to the government were tailored to help the Ambanis wiggle out of an investigation into a graft scandal. Interestingly, three legal notices, each more threatening than the other, reached the magazine in the month of April, demanding complete silence. Caravan took them head on, but not every publisher would have the wherewithal to resist impending SLAPP suits.

The threats to Caravan were benign if compared with what the Ambanis did to “The Polyester Prince”, Hamish McDonald’s 1998 biography of Dhirubhai. The plight of that book is a true testament to the Ambanis’ power of insidious censorship. Incessant threats of injunctions from every high court in India ensured that the book quietly vanished off the shelves.

And why not? McDonald had quoted him — “I don’t break laws, I make laws.”

UPDATE:

If there were any doubts as to the extent of Reliance Industries’ determination to suppress the tiniest whisper of criticism, they are dispelled by the latest fusillade hurled against the authors. This comes in the form of a couple of fresh legal notices laden with preposterous claims and egregious threats.

The first one, dated 22 April, cherrypicks random, disjointed passages from the book to make out a case for libel. Suffice it to say, even prima facie innocuous statements have been included.

Dated 23 April, the second one accuses the authors of malevolent mendacity in publishing and publicising their “pamphlet” (yes, that’s the term used to substantiate the charges of the book being a piece of malicious propaganda), and goes on to claim that even the launch event was designed to malign the companies.

At that event, Guha Thakurta had quoted former Governor of West Bengal Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s statement that “Reliance was a parallel state, brazenly exercising total control over the country’s resources”. But Reliance hasn’t trained its guns on Gandhi; instead it accuses the author of slander. It is not pusillanimity but very sound legal strategy — the modus operandi of SLAPP suits, which the company adopts because taking on Gandhi, a widely respected and renowned public figure, would backfire.

Playing both judge and jury, Reliance determines that a sum of INR 100 crore (10 billion) as “token damages”, to be paid within ten days, would be just restitution. Never before has any plaintiff arrogated to itself such a right even before going to court.

The next claim is much more sinister. The authors are directed to remove all traces of “publicity material” — both in print and on the internet, including the website http://www.gaswars.in/. This patently means that even this particular report has to be taken off. Since when have two corporations been so imperious as to stake claim to sovereignty over the internet?

An earlier version of this article identified the basin in question in the production sharing contract as one Kasturba Gandhi in Gujarat, when it should be Krishna Godavari, off the Bay of Bengal, in Andhra Pradesh. An earlier version also stated that both Reliance Industries Limited (RIL) headed by Mukesh Ambani, and Reliance Natural Resources Limited (RNRL) headed by Anil Ambani, were involved in the sharing contract, when it should only be RIL. This has been corrected.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Apr 14 | Asia and Pacific, Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, Singapore

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Speaking in a Singaporean university seminar room in early March, Lord David Puttnam highlighted the importance of media plurality. He saw it as a means to an end, a way to foster an informed citizenry in a society where no one person or entity has too much influence over the media.

It was an interesting location for him to be talking about media plurality. Thanks to the laws and regulations establish by the People’s Action Party government – the party’s rule has been uninterrupted since Singapore achieved self-governance in 1959 – the country has not had true media plurality for a long time. Most mainstream media organisations are owned by government-linked corporations, and the government also has the power to appoint management shareholders to newspaper companies.

This has resulted in a mainstream media that revolves more around educating Singaporeans along official narratives rather than serving as a Fourth Estate. But as Singaporeans increasing turn to the internet as their source of news and information, websites and blogs are making an unmistakable impact on Singapore’s media landscape.

The Online Citizen (TOC) is a notable example. Launched in 2006, the website is unabashedly political in a country where the subject of politics is often approached with trepidation. “Our specialty is in reporting on social issues and government policy. We tend to focus on cases where policy has affected people in ways that you will not see touted in mainstream media, and we try to increase our readers’ perspective on these issues, so they can think about the way forward,” the TOC core team wrote in an email to Index.

The issues that TOC has covered vary from poverty and homelessness to the exploitation of migrant workers. Commentaries have examined numerous state policies, from public housing to media regulation. It was also one of the major alternative websites that covered the 2011 general Election — the first election in which online and new media was prevalent.

Since then, several new platforms have emerged. They cover a spectrum, from New Nation‘s satirical humour to The Independent Singapore‘s attempt to bring non-mainstream professional journalism to the online sphere. This blossoming of online websites has been accompanied by parallel discussions on social media platforms, especially Facebook and Twitter. Where Singaporeans once only had establishment-dominated mainstream media voices to tune in to, alternative perspectives, criticism and discussion are now common online.

The threat the online community poses to the government’s hegemony has not gone unnoticed. Government figures have said plenty about the dangers of the internet, going so far as to label it a threat that could hamper Singapore’s Total Defence strategy. An acronym, DRUMS, was invented. It stands for Distortions, Rumours, Untruths, Misinformation and Smears.

Defamation suits and warning letters from lawyers have also been issued to various blogs and websites. The Attorney-General’s Chambers is now trying to take legal action against prominent blogger Alex Au, accusing him of having “scandalised the judiciary” – the same charge that British journalist Alan Shadrake faced in 2010.

Legislation has also been invoked to exert some control (or at least influence) over the internet. In 2011, TOC was gazetted by the prime minister’s office as a “political association”. This meant that TOC would not be able to receive any foreign funding, and that anonymous donations made to the website had to be limited to S$5,000 (£2,377) a year. Once that amount is reached, anyone who would like to donate will have to be identified.

The move has limited TOC’s ability to fund its work. “Classifying us as a political website gives potential investors the impression that TOC is aligned with partisan politics, where the truth is we do not align ourselves with any political party. Such an impression has an impact in terms of encouraging people to donate to the website,” TOC explains.

But TOC is not the only website to have felt the government’s “light touch” on the internet. In 2013 the government announced a new licensing regime: popular news websites – defined as those that receive more than 50,000 unique visitors a month – would need to get licenses from the Media Development Authority. They would be required to put down a S$50,000 (£23,772) bond and commit to taking down any material deemed in breach of content standards within 24 hours.

The regime was put in place very quickly, and ten websites were identified for licensing. Only one — Yahoo! Singapore’s news website — was not a website owned by Singapore’s mainstream media corporations and already regulated under other legislation.” The government said that blogs would not be licensed under these rules, but citizen journalists are not so sure. After all, the MDA defines “news reporting” as “any programme (whether or not the programme is presenter-based and whether or not the programme is provided by a third party) containing any news, intelligence, report of occurrence, or any matter of public interest, about any social, economic, political, cultural, artistic, sporting, scientific or any other aspect of Singapore in any language (whether paid or free and whether at regular interval or otherwise) but does not include any programme produced by or on behalf of the Government.” The definition is more than broad enough to encompass the work done by some blogs.

Outside of the licensing regime, three other alternative websites have since been singled out for registration with the MDA. Registering with the MDA requires a website to make all its editorial staff known to the regulators, as well as declare that it will not receive any foreign funding.

The Breakfast Network was asked to register late last year. It chose to shut down instead.

“We didn’t like the idea of being ‘registered’. We started as a pro bono site and some of us didn’t think it was any business of the government to have details of who was doing what,” wrote its former editor-in-chief Bertha Henson in response to Index on Censorship.

The other two websites, The Independent Singapore and Mothership.sg, decided to comply and register. They say that they have never received any foreign funding anyway, and so it’s not made too much of an impact on operations.

“I’m very open with the MDA. I tell the MDA what I do, so they don’t get overly concerned and suspicious and try to shut us down,” said Kumaran Pillai, chief editor of The Independent Singapore.

The restriction of foreign funding might cut off some funding streams for online websites, but Singapore’s blogosphere continues to grow. With the next general election (which has to be called before mid-2016) coming up, alternative websites are getting prepared. Both TOC and The Independent SG are building up to the election. But will establishment sources be willing to engage in their attempts at providing alternative coverage?

“If they won’t give us the press releases, it’s their loss,” Pillai said with a shrug. “They are going to lose out in the long run.”

This article was originally published on 23 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Apr 14 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

A shot from the trailer of Halawet Rooh (Image: Mohamed Elsobky/YouTube)

Just as Egyptian free expression advocates were celebrating the decision by Egypt’s State Censorship Board to allow the screening of Darren Aronofsky’s Biblical epic Noah, news of the withdrawal of Lebanese diva Haifa Wehbe’s new film Halawet Rooh (Beauty of the Soul) from theatres in Egypt put a damper on their cautiously optimistic mood. The fact that the decision to suspend the screening of the controversial film was made by interim Prime Minister Ibrahim Mehleb — rather than by the censors — has added fuel to the fire.

On Wednesday, the premier ordered the film to be removed from cinemas and sent back to the State Censorship Board for re-evaluation. The move led Ahmed Awad, the head of the State Censorship Board to tender his resignation, saying he was “not consulted” and categorically rejects government interference in his work.

Former Culture Minister Emad Abu Ghazy reminded the prime minister of a court ruling forbidding interference in the work of the independent censorship board. “The Premier has no right to suspend the screening of the film,” Abu Ghazy told AFP.

Popular TV talk show host Ibrahim Eissa meanwhile, cautioned that the ban does not auger well for freedom of expression.”Those who ban films today for damaging public morality will in future, ban films for political reasons,” he warned in an episode of his show “Hunna Al Kahera” broadcast on the privately owned CBC Channel.

Rights activists and groups have also expressed concern over the suspension of the film’s screening, saying the move is part of a wider clampdown on artistic expression in Egypt. In his column in Saturday’s edition of the independent newspaper Al-Shorouq, film critic Kamal Ramzy chided the government for not having learnt history’s lessons on censorship. “Instead of focusing on problems of corruption and the rule of law, the prime minister is instead, more occupied with censorship,” he lamented.

Mehleb meanwhile, downplayed the criticism levelled at him. At a meeting with intellectuals and literary figures on Saturday, he insisted that “there is a clear cut distinction between freedom of artistic expression and creativity on the one hand, and infringement on moral values on the other”.

The premier’s decision to suspend the screening of the film came in the wake of an outcry from conservatives in Egypt who denounced the film on social media networks as “obscene” and “a threat to public morality”. Oddly enough, some “liberal” Egyptians too, have joined the online campaigns accusing Ahmed El Sobky, the film’s producer of “destroying an entire generation” and being “more dangerous than bombs and missiles”. El Sobky’s trademark films are often “low quality” productions characterised by a mix of violence, belly dancing and sexually explicit scenes. His target audience are generally the uneducated, low income youth who traditionally celebrate public holidays by going to the cinema.

Film critics have also decried the film as “sexually provocative,” lambasting lead actress Haifa for “revealing too much flesh”. “There is hardly a scene in which Haifa does not appear half nude,” scoffed critic Ramy Abdel Razak in his review published Thursday in the independent daily Al Masry El Youm.

Critics question how a particularly steamy scene in which Haifa’s clothes are ripped off by a rapist, got past the State Censor board. Overlooking the fact that the film was rated “Adults Only” — which meant it was inaccessible to children under 16 — Egypt’s National Council for Childhood warned in a statement released last week, that the film was “harmful to minors” and “violates public morality”.

The “raunchy” film had been in cinemas for two weeks before it was removed and had reportedly grossed some £84,100 in its first week in theatres. At the time of publication, a two-minute trailer for the film on YouTube had over 3,6 million views.

Described by critics as a “poor imitation of Italian director Giuseppe Tornatore’s widely-acclaimed Malena”, the film tells the story of a young boy’s obsession with a beautiful nightclub singer. The woman, whose husband is abroad, is pursued by the men in her working class neighbourhood and her ardent young admirer subsequently takes it upon himself to protect her.

Fifteen year-old Karim El Abnoudi, who plays the role of the boy infatuated with Rooh, has reportedly been verbally harassed at his school and on the streets, with his classmates and some laymen — angered by what they had read or heard about the film — hurling insults at him and calling him “an infidel”.

The withdrawal of the film from theatres has fuelled fears among some secularists and rights organisations that increased censorship is stifling freedom of artistic expression and creativity in Egypt. In March, the State Censorship Board banned 20 music videos from Egyptian TV Channels for allegedly containing “explicit content”. In another sign that the interim government is putting the lid on artistic expression, a misdemeanour court in the Southern Egyptian province of Bani Suef in March upheld a verdict against Egyptian author and rights activist Karam Saber, who eight months earlier had been sentenced in absentia to five years in prison and LE1000 in bail for “blasphemy”. In June 2013. Saber was convicted on charges of “contempt of religion” and “inciting sedition” in a collection of short stories he wrote two years earlier titled Where is God? Both Al Azhar (the country’s highest Islamic authority ) and the Coptic Orthodox Church had earlier concurred in the opinion that the book was “blasphemous” and “ought to be banned”.

In a joint statement released in September (in the wake of the sentence handed down to Saber), 46 Arab Human Rights Organisations expressed concern for the diminishing space for free artistic expression and creativity. The Arab Network for Human Rights Information also said the verdict against Saber “belies any notion of respect for human rights by the state and violates provisions in the new constitution guaranteeing freedom of creativity and artistic expression”.

A provision in the new charter, endorsed by an overwhelming 98% of voters in a popular referendum in January, guarantees freedom of thought and opinion stipulating that any individual “has the right to express his opinion and to publicise it verbally or in writing or by other means”. Another provision in the 2014 constitution guarantees freedom of literary and artistic creation, stating that “the state shall promote art and literature, sponsor creators and protect their creations, providing the necessary means to achieve this”.

Many artists and writers had joined the mass protests in January 2011, hoping that the revolution would bring an end to decades of repression. For a short period after the fall of authoritarian president Hosni Mubarak, Egypt’s artists and literary figures capitalised on their new-found freedoms, tackling subjects long off limits to them — like sex and religion.The rise of Islamists to power in 2012 , however brought new limitations to the short-lived free flow of artistic and creative expression. New legislation was introduced by the Islamist-dominated parliament, banning art with obvious sexual references as well as concerts featuring female singers. The downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood regime in July 2013 rekindled hopes for an end to censorship and suppression of creativity. But in the new restrictive cultural atmosphere — reminiscent of the Mubarak era — these hopes have been quickly dashed, giving way to disappointment, frustration and fear.

“It is ironic that the ban on Wehbe’s film would come from the interim government that replaced the ousted Islamist regime,” prominent blogger Zeinobia wrote last week. Many of the liberal Egyptians who joined the uprising against the Muslim Brotherhood president in July last year had said they were protesting against “religious fascism” and had hoped the new government would be secular and more democratic.

“The interim government has demonstrated that it is more Islamic than the Islamists,” lamented Sameh Kassem, culture editor at the independent Al Bawabh news website .

“The withdrawal of Wehbe’s film from theatres and the verdict against Saber are attempts by the interim government to appease the ultra-orthodox Salafis ahead of presidential elections scheduled on 28 and 29 May,” he told Index.

Egypt’s Salafis, the ultra-conservative Islamist movement that had initially backed ousted Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi, later decided to side with the military and lent its support to the military-backed interim government after his deposition.

“The military-backed authorities are trying to woo the Salafis to guarantee their votes for former military chief Abdel Fattah El Sisi in the upcoming elections,” Kassem said.

This article was originally posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Apr 14 | Canada, Digital Freedom, News and features

(Image: Shutterstock)

Knowledge, claimed Francis Bacon, is power. It is also money. Which is why Canada’s newly drafted Digital Privacy Act, Bill S-4, is considered by the privacy fraternity to be a demon of some proportions. As Gillian Shaw of the Vancouver Sun (Apr 14) explains, “If you worry Big Brother is reporting everything you do on the Internet, changes introduced to Canada’s privacy legislation last week may prove your worries are not totally unfounded.”

The bill has striking similarities to proposed US legislation that proved so contentious it wound up in the deep freeze of US Congressional contemplation. The US Cyber Information Sharing and Protection Act (CISPA) would have granted blanket immunity to companies sharing user content with governments on the pretext of a pressing “cyber threat”. S-4, however, goes further, increasing the sharing of such user information with parties beyond government to private organisations.

The aim of such legislation is twofold: re-enforcing copyright barriers via the umbrella pretext of fighting crime and contractual infringement while eroding privacy protections. The snooping incentive in the case of Bill S-4 is considerable: to monitor those habits of downloading and use of material that just might breach intellectual property laws.

As with laws purportedly targeting digital piracy, it does more. University of Ottawa’s law professor, Michael Geist, has kept his eye on developments in the area of Canadian privacy law for some time. He is far from impressed by the latest measures on the part of the Canadian government. “Unpack the legalese and you find that organizations will be permitted to disclose personal information without consent (and without a court order) to any organization that is investigating a contractual breach or possible violation of any law” (Vancouver Sun, Apr 14).

Other effects follow on from S-4, read along with C-13 (the “cyber-bullying bill). Immunity to organisations disclosing subscriber or customer information to law enforcement authorities, or copyright trolls, will be granted. The mere fact that an investigation is taking place, be it into contractual breach, actual or potential, can trigger the need to disclose the confidential data of users of the service. Those users will not be informed of such disclosure, and organisations engaging in such acts will be under no obligation to do so.

One of the amending provisions states, for instance, that “an organization may collect personal information without the knowledge or consent of the individual only if it is reasonable to expect that the collection with the knowledge or consent of the individual would compromise the availability or the accuracy of the information and the collection is reasonable for purposes related to investigating a breach of an agreement or a contravention of the laws of Canada or a province.”

Geist makes various important points, noting how judicial management has been indispensable in keeping the information trawlers at bay. He cites the file sharing case of Voltage Pictures, a U.S. company which sought an order asking the internet service provider TekSavvy to disclose the names and addresses of thousands of users it claimed had infringed copyright. TekSavvy requested the Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic to intervene for the purposes of informing the court over privacy and copyright trolling concerns.

The disclosure was granted by the federal court, but the move came with various safeguards with the intention of discouraging copyright trolling lawsuits. The point was considered fundamental by the court – compelling ISPs to reveal the private details of their subscribers would create a monumental strain on the court system. Many infringements would be of a non-commercial nature, and taking these to court would see a needless use of judicial resources. Even more significant, the cap of $5000 on liability for such non-commercial infringements “may be miniscule compared to the cost, time and effort in pursuing a claim against the subscriber.”

The court found Voltage’s conduct in seeking such disclosure potentially improper, though not sufficient to refuse the motion. Instead, the company was asked to guarantee that any subscriber information obtained would remain confidential, not be used for any other purposes, not be made public and not be disclosed to third parties. The fees for TekSavvy behind the disclosure would also be covered by Voltage.

The decision suggests heavy judicial oversight over the grants of such disclosure motions. Important safeguards include court involvement over the contents of the “demand letter” sent to subscribers. As Geist notes, the letter must include the message that “no Court has yet made a determination that such subscriber has infringed or is liable in any way for payment of damages.”

S-4 would make such protections redundant, stifling court scrutiny and enabling a ready disclosure of private user information between companies. In Geist’s words, “If Bill S-4 were the law, the court might never become involved in the case. Instead, Voltage could simply ask TekSavvy for the subscriber information, which could be legally disclosed (including details that go far beyond just name and address) without any court order and without informing their affected customer.”

The legislative moves on the part of the Canadian government reveal the addictive nature of such copyright legislation. Privacy is a subsidiary concern to the use of material provided by an ISP, while broadening the policing function against illegal use of information is paramount. The current Digital Privacy Act seems a less than distant echo of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), Bill C-29. The government has evidently been there, but hasn’t yet done that.

Warrantless disclosure of private information is the holy grail of government regulation. The sacrificial lamb is always the privacy of citizens. This, goes the official drum roll, is necessary to protect the public. In truth, it is designed to protect corporate legal interests and pull down the walls of data protection.

This article was posted on 23 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Apr 14 | Africa, News and features, Swaziland

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

The case against human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor of the independent Nation magazine, Bheki Makhubu, resumes today in Swaziland after adjourning over Easter. The two were arrested last month, and face charges of “scandalising the judiciary” and “contempt of court”. The charges are based on two separate articles, written by Maseko and Makhubu and published in the Nation, which strongly criticised Chief Justice Michael Ramodibedi, levels of corruption and the lack of impartiality in the judicial system in Swaziland.

Makhubu’s home was raided by armed police, and the men were initially denied the right to a fair trial when their case was heard privately in the judge’s chambers. They were also denied bail as they were deemed to pose a security risk. Over the last few weeks, they have been released, and re-arrested in a highly unconventional course of events, so far spending 26 days in custody.

Last week, armed police blocked the gates of the High Court and stopped members of the public and banned political parties from attending the case. Continuous requests to move the case to a larger courtroom so that journalists, observers and family members could monitor proceedings have been refused. The Judicial Service Commission (JSC) said this was in order to minimise disturbances in the court.

There was public outcry as the two men appeared in court bound by leg irons. This highly unusual treatment has been described as “inhumane and degrading” by the Swaziland Coalition of Concerned Civic Organisations (SCCCO). When questioned on the issue, Mzuthini Ntshangase, Commissioner of His Majesty’s Correctional Services told the media to “stay away from [commenting on] security matters”.

Maseko and Makhubu’s lawyers have claimed that the arrests are a blatant form of judicial harassment intended to intimidate the accused and are unconstitutional, unlawful and irregular. They are currently being held in a detention centre in the capital Mbabane, and journalists have been prevented from visiting.

The local press has faced severe censorship of its reporting on the case. The JSC warned the media and public against commenting on the case. It argues that: “[Freedom of expression] is not as absolute as the progressive organisations and other like-minded persons seem to suggest.” Managing editor of The Observer newspaper, Mbongeni Mbingo commented on the case in his editorial: “For now though, the rest of us will do well to toe the line, and hold our breath and mourn in silence for our beautiful kingdom.” One local journalist said he was scared to comment on the situation for fear of arrest – or worse.

Maseko and Makhubu’s articles highlighted the disturbing case of Bhantshana Gwebu, a civil servant employed to monitor the abuse of government vehicles, who was arrested after stopping a high court judge’s driver for driving without the required documentation. Gwebu was detained for a week without charge and initially denied the right to representation. He now also faces a contempt of court charge.

In his article, Maseko wrote that “fear cripples the Swazi society, for the powerful have become untouchable. Those who hold high public office are above the law. Those who are employed to fight corruption in government are harassed, violated and abused”. He described how the Swazi people have lost faith in the institutions of power, as cases like Gwebu’s show how such institutions are being used to settle personal scores “at the expense of justice and fairness”.

Their case has sparked both local and international condemnation, from civil society organisations and the Swazi business community, as well as EU representatives and the American Embassy. “The only crime in this case is judges abusing the judicial system to settle personal scores,” says CPJ Africa advisory coordinator Mohamed Keita. The Law Society of Swaziland has called the arrests an “assassination of the rule of law”. They claim that the Swazi court had become the persecutor instead of the defender of the rights and freedoms of the people. But many in the country are still scared to speak out. The media operates under strict government imposed regulations. Journalists are often forced to exercise various forms of self-censorship when reporting on sensitive issues.

The arrests and the continuation of an abysmal human rights record could have wider implications for Swazi society and the economy. The situation threatens to further derail Swaziland’s highly beneficial African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) with the United States, which is currently being reviewed in Washington. AGOA requires that a country demonstrates that it is making progress towards the rule of law and protection of human rights — including freedom of expression. “There is peace in Swaziland,” the head of the country’s Federation of Trade Unions, once said, “but it’s not real peace if every time there is dissent, you have to suppress it. It’s like sitting on top of a boiling pot.”

This article was originally posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Apr 14 | Magazine, Politics and Society

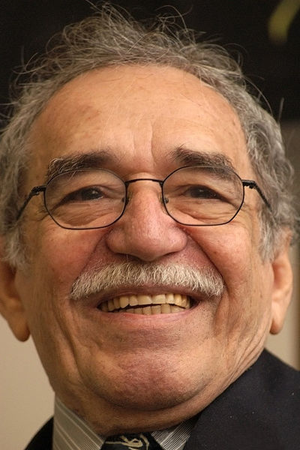

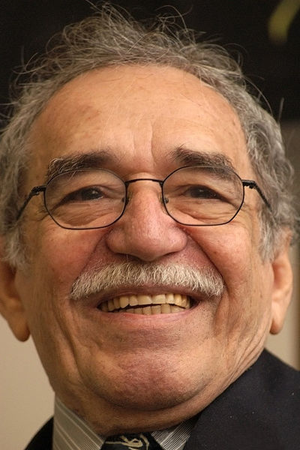

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for Index on Censorship magazine in 1997. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control”

Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April, wrote this piece on the evolution of journalism for Index on Censorship magazine in 1997. Before gaining worldwide acclaim for novels including One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, Márquez was a journalist for newspapers in Colombia and Venezuela. This piece shares his love of the profession and his concern that reporters have become “lost in labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control”

Some 50 years ago, there were no schools of journalism. One learned the trade in the newsroom, in the print shops, in the local cafe and in Friday-night hangouts. The entire newspaper was a factory where journalists were made and the news was printed without quibbles. We journalists always hung together, we had a life in common and were so passionate about our work that we didn’t talk about anything else. The work promoted strong friendships among the group, which left little room for a personal life.There were no scheduled editorial meetings, but every afternoon at 5pm, the entire newspaper met for an unofficial coffee break somewhere in the newsroom, and took a breather from the daily tensions. It was an open discussion where we reviewed the hot themes of the day in each section of the newspaper and gave the final touches to the next day’s edition.

The newspaper was then divided into three large departments: news, features and editorial. The most prestigious and sensitive was the editorial department; a reporter was at the bottom of the heap, somewhere between an intern and a gopher. Time and the profession itself has proved that the nerve centre of journalism functions the other way. At the age of 19 I began a career as an editorial writer and slowly climbed the career ladder through hard work to the top position of cub reporter.

Then came schools of journalism and the arrival of technology. The graduates from the former arrived with little knowledge of grammar and syntax, difficulty in understanding concepts of any complexity and a dangerous misunderstanding of the profession in which the importance of a “scoop” at any price overrode all ethical considerations.

The profession, it seems, did not evolve as quickly as its instruments of work. Journalists were lost in a labyrinth of technology madly rushing the profession into the future without any control. In other words: the newspaper business has involved itself in furious competition for material modernisation, leaving behind the training of its foot soldiers, the reporters, and abandoning the old mechanisms of participation that strengthened the professional spirit. Newsrooms have become a sceptic laboratories for solitary travellers, where it seems easier to communicate with extraterrestrial phenomena than with readers’ hearts. The dehumanisation is galloping.

Before the teletype and the telex were invented, a man with a vocation for martyrdom would monitor the radio, capturing from the air the news of the world from what seemed little more than extraterrestrial whistles. A well-informed writer would piece the fragments together, adding background and other relevant details as if reconstructing the skeleton of a dinosaur from a single vertebra. Only editorialising was forbidden, because that was the sacred right of the newspaper’s publisher, whose editorials, everyone assumed, were written by him, even if they weren’t, and were always written in impenetrable and labyrinthine prose, which, so history relates, were then unravelled by the publisher’s personal typesetter often hired for that express purpose.

Today fact and opinion have become entangled: there is comment in news reporting; the editorial is enriched with facts. The end product is none the better for it and never before has the profession been more dangerous. Unwitting or deliberate mistakes, malign manipulations and poisonous distortions can turn a news item into a dangerous weapon.

Quotes from “informed sources” or “government officials” who ask to remain anonymous, or by observers who know everything and whom nobody knows, cover up all manner of violations that go unpunished.But the guilty party holds on to his right not to reveal his source, without asking himself whether he is a gullible tool of the source,manipulated into passing on the information in the form chosen by his source. I believe bad journalists cherish their source as their own life – especially if it is an official source – endow it with a mythical quality, protect it, nurture it and ultimately develop a dangerous complicity with it that leads them to reject the need for a second source.

At the risk of becoming anecdotal, I believe that another guilty party in this drama is the tape recorder. Before it was invented, the job was done well with only three elements ofwork: the notebook,foolproof ethics and a pair of ears with which we reporters listened to what the sources were telling us. The professional and ethical manual for the tape recorder has not been invented yet. Somebody needs to teach young reporters that the recorder is not a substitute for the memory, but a simple evolved version of the serviceable, old-fashioned notebook.

The tape recorder listens, repeats – like a digital parrot – but it does not think; it is loyal, but it does not have a heart; and, in the end, the literal version it will have captured will never be as trustworthy as that kept by the journalist who pays attention to the real words of the interlocutor and, at the same time, evaluates and qualifies them from his knowledge and experience.

The tape recorder is entirely to blame for the undue importance now attached to the interview. Given the nature of radio and television, it is only to be expected that it became their mainstay. Now even the print media seems to share the erroneous idea that the voice of truth is not that of the journalist but of the interviewee. Maybe the solution is to return to the lowly little notebook so the journalist can edit intelligently as he listens, and relegate the tape recorder to its real role as invaluable witness.

It is some comfort to believe that ethical transgressions and other problems that degrade and embarrass today’s journalism are not always the result of immorality, but also stem from the lack of professional skill. Perhaps the misfortune of schools of journalism is that while they do teach some useful tricks of the trade, they teach little about the profession itself. Any training in schools of journalism must be based on three fundamental principles: first and foremost, there must be aptitude and talent; then the knowledge that “investigative” journalism is not something special, but that all journalism must, by definition, be investigative; and, third, the awareness that ethics are not merely an occasional condition of the trade, but an integral part, as essentially a part of each other as the buzz and the horsefly.

The final objective of any journalism school should, nevertheless, be to return to basic training on the job and to restore journalism to its original public service function; to reinvent those passionate daily 5pm informal coffee-break seminars of the old newspaper office.

Index on Censorship magazine is proud to have had Gabriel García Marquez among its contributors – a long list which has also included Samuel Beckett, Chinua Achebe, Salman Rushdie and many other literary greats. Printed quarterly, the magazine mixes long-form journalism with short stories and extracts from plays – some of which have been banned or censored around the world. Subscribe here

22 Apr 14 | India, News and features, Politics and Society

Gujarat Chief Minister and BJP prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi filed his nomination papers from Vadodara Lok Sabha seat amid tight security on April 6. (Photo: Nisarg Lakhmani / Demotix)

Electioneering for the Indian elections of 2014 has reached a fever pitch. Never before in the history of modern India has it seemed likely that the country is ready to cut its cord with the Congress Party’s Gandhi family, and never before has its chief opposition party, the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) been projected as the sole inheritance of one man – Narendra Modi.

The “greatest show on Earth” – the Indian elections – is underway. There are 37 days of polling across 9 states, with a 814 million strong electorate, and more than 500 political parties to choose from. The hoardings all seem to scream the “development” agenda, but unfortunately in India, this conversation seems to be skating on thin ice. Cracks quickly appear, and beneath the surface, political parties seem to be indulging in the same hate speech, communal politicking and calculations that work to polarise the electorate and garner votes.

Hate speech in India is monitored by a number of laws in India. These are under the Indian Penal Code (Sections 153[A], Section 153[B], Section 295, Section 295A, Section 298, Section 505[1], Section 505 [2]), the Code of Criminal Procedure (Section 95) and Representation of the People Act (Section 123[A], Section 123[B]). The Constitution of India itself guarantees freedom of expression, but with reasonable restricts. At the same time, in response to a Public Interest Litigation by an NGO looking to curtail hate speech in India, the Court ruled that it cannot “curtail fundamental rights of people. It is a precious rights guaranteed by Constitution… We are 128 million people and there would be 128 million views.” Reflecting this thought further, a recent ruling by the Supreme Court of India, the bench declared that the “lack of prosecution for hate speeches was not because the existing laws did not possess sufficient provisions; instead, it was due to lack of enforcement.” In fact, the Supreme Court of India has directed the Law Commission to look into the matter of hate speech — often with communal undertones — made by political parties in India. The court is looking for guidelines to prevent provocative statements.

Unenviably, it is the job of India’s Election Commission to ensure that during the elections, the campaigning adheres to a strict Model Code of Conduct. Unsurprisingly, the first point in the EC’s rules (Model Code of Conduct) is: “No party or candidate shall include in any activity which may aggravate existing differences or create mutual hatred or cause tension between different castes and communities, religious or linguistic.” The third point states that “There shall be no appeal to caste or communal feelings for securing votes. Mosques, churches, temples or other places of worship shall not be used as forum for election propaganda.”

This election season, the EC has armed itself to take on the menace of hate speeches. It has directed all its state chief electoral officers to closely monitor campaigns on a daily basis that include video recording of all campaigns. Only with factual evidence in hand can any official file a First Information Report (FIR), and a copy of the Model Code of Conduct is given along with all written permissions to hold rallies and public meetings.

As a result, many leaders have been censured by the EC for their alleged hate speeches during the campaign. The BJP’s Amit Shah was briefly banned by the EC for his campaign speech in the riot affected state of Uttar Pradesh, that, Shah had said that the general election, especially in western UP, “is one of honour, it is an opportunity to take revenge and to teach a lesson to people who have committed injustice”. He has apologized for his comments. Azam Khan, a leader from the Samajwadi Party, was banned from public rallies by the EC after he insinuated in a campaign speech that the 1999 Kargil War with Pakistan had been won by India on account of Muslim soldiers in the Army. The EC called both these speeches, “highly provocative (speeches) which have the impact of aggravating existing differences or create mutual hatred between different communities.”