Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

This is the ninth of a series of posts written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board.

Members of the board were asked to write a blog discussing one free speech issue in their country. The resulting posts exhibit a range of challenges to freedom of expression globally, from UK crackdowns on speakers in universities, to Indian criminal defamation law, to the South African Film Board’s newly published guidelines.

Lejla Becar is a member of the Index youth advisory board. Learn more

In 2005, the chair of Visoko municipality cancelled a concert due to be performed by Skroz, a rock band from Bosnia and Herzegovina. He justified his decision by saying that the concert and the sponsor (a famous beer brand) would be insulting for Muslims and Muslim youth.

These decisions riled up both the organisers of the events and also citizens, both Muslim and non-Muslim. One of the main organisers was Adnan Jašo Jašarspahić, editor of independent radio station Radio Q. He was to face consequences in the years to come due to his decision not to obey the chair and ignore the cancellation of the Skroz concert. It was held 15 days after cancellation.

This was not an isolated event. In 2006 Croatian band Let 3 were not allowed to perform in Travnik, a small municipality in central Bosnia. In 2008, Bosnian group Dubioza Kolektiv were banned from performing in Goražde. In the meantime, the Communications Regulatory Agency (CRA) penalised Bosnian radio station Radio 202 — fining them more than €5,000 — for playing hip-hop music on air. The agency stated it had been offensive.

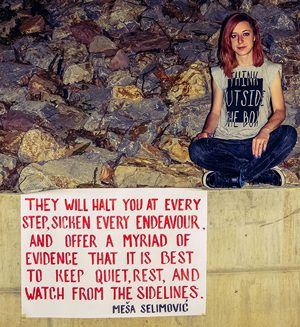

The situation now? In my town, cultural events for youth are a phenomena. More and more young people are leaving, turning to radical Islam or simply living within an oppressive system without complaint. The people fighting the system were silenced. Ten years of violating the right to freedom of expression took its toll and now the government has succeeded in creating a society that is obedient, ignorant and passive.

Lejla Becar, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Related:

• Anastasia Vladimirova: A ruthless crackdown on independent media

• Simeon Gready: An over-the-top regulation policy

• Ravian Ruys: Without trust, free speech suffers

• Muira McCammon: GiTMO’s linguistic isolation

• Jade Jackman: An act against knowledge and thought

• Harsh Ghildiyal: Defamation is not a crime

• Tom Carter: No-platforming Nigel

• Matthew Brown: Spying on NGOs a step too far

• About the Index on Censorship youth advisory board

• Facebook discussion: no-platforming of speakers at universities

Sara, Nataša, Elma and Lejla (clockwise, from top left) are local correspondents for Balkan Diskurs.

At first glance it’s easy to mistake Bosnia and Herzegovina’s media landscape as one of promise. With a constitution that guarantees freedom of the press, a large number of media outlets, and a financially independent regulatory body, the small Balkan country performs relatively well by Southeast European standards.

But on closer inspection such freedoms are a mere façade, hiding this divided, post-war state’s continued struggle with a highly polarised and politicised media. Despite appearances, many of the fundamental aspects of media freedom face significant challenges and, according to recent reports, the situation is only worsening.

Lejla, Nataša, Sara and Elma live their lives within this decline. All in their early to mid-twenties, they represent a generation that had little to do with the war but that bears the burdens of its legacy nonetheless. All four are full-time students, but in their spare time, they’re working towards a fairer, freer future across Bosnia as local correspondents for Balkan Diskurs – a non-profit platform created and run by a regional network of journalists, artists and activists, dedicated to providing objective news (full disclosure: the author of this article works with Balkan Diskurs).

“The media is in the hands of the government. Certain persons dictate which news to publish, how much, and so on,” explains Nataša, from Bijeljina, the second largest city in predominantly Bosnian Serb Republika Srpska, one of the country’s two constituent entities. Sara, from Jajce, confirms that her impression of media within her entity, the predominantly Bosniak and Bosnian Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is the same: “They should be working for public benefit, [but] they are mostly just an arm of parties and political elites.”

Such criticisms will come as little surprise to those who have been tracking the state of media freedom in Bosnia. Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project, Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders have pointed to mounting levels of political pressure and media partisanship. Such pressure takes a variety of forms, but largely stems from the country’s ongoing ethnic and political cleavages. Many media outlets, including Bosnia’s three public broadcasters, are organised along ethnic lines, while some are either aligned, openly affiliated or funded by specific political parties or figures.

As a consequence, skewed media coverage is commonplace and corruption and crime often goes unreported. As Lejla explains: “Many things happening in Visoko are never reported in media, for reasons unknown to me, and those are not small things either – for example there were multiple shootings last month and very little was written about it.”

Media bias, she added, “is most obvious though when political topics from the Federation and Republika Srpska are compared”.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) is a regular victim of such political bias. Much of the local media coverage of the tribunal is skewed and selective. For example, during the closing days of the case against Radovan Karadžić, the Sarajevo-based Dnevni Avaz focused on the prosecution’s charges against the former Bosnian Serb politician, while Banja Luka-based Nezavisne Novine focused solely on his defense and protestations of innocence. Furthermore, only “a handful” of independent organisations in Republika Srpska are known to report on trials within Bosnia’s local War Crimes Court.

Equally as worrying is the fate of those who resist such political pressures. It is not uncommon for journalists and media outlets in both of Bosnia’s entities to face harassment from political, religious and business leaders. Last December, Republika Srpska’s anti-corruption police raided the Sarajevo headquarters of Klix.ba with the aim of identifying the source of a recording published on the news site. Nor are Bosnia’s regulatory agencies immune, as demonstrated by a spate of unidentified attacks against the country’s press council in 2014.

Index report: Europe’s journalists face growing climate of fear

Political pressure is not the only threat to media in freedom in Bosnia. The country’s deteriorating economic situation also presents serious challenges. “Journalists sell their names for trinkets, I guess due to lack of other options or because they are used to taking the easy way out,” Elma explains. “I have witnessed various manipulations by local ‘wannabe journalists’ who publish every single piece of information that lands in their inbox without checking it, not being aware of the consequences,” she adds.

This thoughtless reproduction of news frequently leads to the rapid spread of false information, as demonstrated by the whirlwind of stories surrounding Bosnia’s protests last spring. This phenomenon is only exacerbated by a strong culture of social media use and low levels of media literacy. “The problem is anyone who has internet access can start their own portal or a Facebook page where they will write whatever they want in anyway they see fit… and many people lack critical thinking,” says Elma.

This sad truth has a silver lining though, and it is one all four women subscribe to through their work with Balkan Diskurs and within their local communities: Bosnia’s citizens also have the potential to change the media landscape. “Thinking with your own head and not being a sponge that soaks up everything that is offered [is important],” claims Elma.

Meanwhile her colleagues underline the promise of independent media in terms of media freedom. “Balkan Diskurs gives my voice an opportunity to be heard, so that stories that others keep quiet about can be told; to present my town in a different, more real light. That opportunity, for me, is priceless,” concludes Lejla.

Balkan Diskurs is a non-profit, multimedia platform created and run by a regional network of journalists, bloggers, multimedia artists, and activists who came together in response to the lack of objective, relevant, invigorating, independent media in the Western Balkans. In partnership with Index on Censorship, the site is supporting efforts to map the state of media freedom in Europe.

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This article was posted on 27 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Press organisations and representatives have strongly condemned a police raid on Bosnia news site Klix.ba that took place on 29 Dec. Authorities are trying to uncover the source of a recording that is said to be of the Republika Srpska Prime Minister Zeljka Cvijanovic.

During the recorded conversation a woman’s voice can be heard admitting that her party bought two MPs to ensure its majority in the national assembly.

Irfan Nefic, a police spokesman, said the raid by about half a dozen police officers was ordered by a Sarajevo court, the Associated Press reported.

The search started at 8.30 am on Monday, 29 December 2014, and lasted more than seven hours. Four Klix.ba workers were held at their offices for questioning. During the investigation police copied materials from the newsroom’s computers. At a post raid press conference, Dario Simic, the portal director, and Jasmin Hadziahmetovic, editor in chief, said that police seized 19 computers hard drives, USB memory flash-sticks, CDs, documents, notes and their private mobile phones.

The raid followed the interrogation of Simic and Hadziahmetovic by Banja Luka police on 4 December 2014. Police had demanded they reveal the identity of the person that gave them the recorded conversation. The journalist and the director of the portal refused to identify their source. The incriminating recording was posted online in mid-November, after the Bosnian general elections, local media reported.

National journalists associations called the raid a dark day for Bosnian journalism and characterized the police action as “attack on the publics’ right to know and to be informed,” said Dario Novalic, the head of the Press Council in Bosnia, a self-regulatory body for print and online media.

“Such an act, of the worst kind of pressure on the freedom of information and media freedom, is a direct attempt of deterring journalists from publishing information in the public’s interest and sends a message of what will happen to any media who publishes in the public’s interest,” Novalic said.

Borka Rudic, secretary general of the Bosnian Journalists Association, said that journalists have the right to protect their sources and that the raid is “unacceptable”. “This is the most brutal attack on freedom of speech and journalist rights ever recorded in Bosnia,” Rudic said.

Association of Journalists of the Republika Srpska strongly condemned the police raid and appealed to international organizations to put pressure on local institutions to respect media freedom.

OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović said that the protection of sources is one of journalists’ key privileges and it must be safeguarded. “Interrogation and pressure on members of the media to reveal their sources is simply unacceptable,” Mijatović said.

She urged the authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina to do their utmost to stop persecuting journalists and to respect their right to protect their sources.

“This is a grave and disproportionate intrusion into the journalists’ right to report about public interest issues,” Mijatović said. “While fully recognizing the importance of rule of law, I consider this case to constitute unacceptable treatment of the media in a democratic society.”

Al Jazeera Balkans reported that the police are investigating how the media got the recording. Officials suspect that the recording was obtained by unauthorized phone tapping.

After the raid, a police officer struck a photographer with a backpack because he was unhappy he had been photographed. The incident was recorded by a TV station’s cameraman.

For more on media violations in Bosnia, visit mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

This article was posted on Jan 2, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Rasul Jafarov, Arif Yunus and Leyla Yunus (Photos: Rasul Jafarov (© IRFS), Arif and Leyla Yunus (© HRHN))

60 NGOs from 13 Human Rights Houses call upon the Azerbaijani authorities, in their joint letter to President Ilham Aliyev, to immediately and unconditionally release Leyla Yunus, Arif Yunus and Rasul Jafarov, and lift all charges held against them. The NGOs also repeat their previous call to release Anar Mammadli and Bashir Suleymanli, and join calls for the release of Hasan Huseynli.

On 28 April 2014 Leyla Yunus, Director of the Institute for Peace and Democrac, and her husband historian Arif Yunus, were prevented from leaving the country at Baku’s airport. Leyla Yunus and her husband Arif Yunus were arrested on 30 July 2014. On that day, Leyla Yunus was sentenced to 3-months pre-trial detention, whilst her husband was placed under police guard and not allowed to leave Baku. The charges brought against Leyla Yunus are those of state treason (article 274 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan), large-scale fraud (article 178.3.2), forgery (article 320), tax evasion (article 213), and illegal business (article 192). Arif Yunus was arrested on 5 August 2014 and also sentenced to 3-months pre-trial detention.

The NGOs state in their joint letter to President Aliyev of 5 August 2014 that they are in particular concerned about Leyla Yunus’ health whilst in detention. She suffers from diabetes and needs appropriate medication, as well as arrangements to eat at certain times, necessary to control the illness. We worry that the conditions in detention will have a detrimental effect on her health condition, as it appears that she is to date not provided with adequate health care.

In July 2014, the bank accounts of, amongst others, human rights defender Rasul Jafarov were frozen as part of a broader investigation into numerous NGO’s. On 25 July he was refused to leave the country. Rasul Jafarov was arrested on 2 August 2014, and sentenced to 3 months pre-trial detention on charges of tax evasion (article 213 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan), illegal business (article 192) and abuse of authority (article 308.2).

On 14 July 2014, Hasan Huseynli, was sentenced to 6 years in prison. He was convicted on charges of armed hooliganism and unlawfully carrying a cold weapon.

The right to freedom of association is at the heart of the charges held against these human rights defenders. In essence they are deprived of their right to work in the defence of human rights. While registration of NGOs and grants to NGOs has become mandatory in Azerbaijan, authorities continue deny registration. Independent NGOs face continuous investigations and human rights defenders are being banned from travelling abroad, depending on their willingness to find agreements with the government, including agreements on their professional activities and their public statements.

Restrictions to laws affecting the right to freedom of association have been widely criticised since October 2011. Such legislation de facto criminalises human rights defenders in Azerbaijan, not for their wrong doing, but rather for the fact that working for an NGO, which does not have the blessing of the government, has become difficult in Azerbaijan. United Nations experts stated ahead of the Presidential elections that they “observed since 2011 a worrying trend of legislation which has narrowed considerably the space in which civil society and defenders operate in Azerbaijan.” The order given to the Human Rights House Azerbaijan in March 2011 to cease all its activities is a consequence of such policies.

The NGOs call upon the Azerbaijani authorities, in their joint letter to President Ilham Aliyev of 5 August 2014, to immediately and unconditionally release Leyla Yunus, Arif Yunus, Rasul Jafarov, and lift all charges held against them. The NGOs see this pre-trial detention of Leyla Yunus, Arif Yunus and Rasul Jafarov as a way to silence them. The NGOs also repeat their previous call to release Anar Mammadli and Bashir Suleymanli, and join calls for the release of Hasan Huseynli.

The NGOs further call upon the Azerbaijani authorities to take appropriate measures to put an end to the attacks, detention and harassment of human rights defenders, journalists and activists, and to take steps in order to foster a safe environment for them, in line with Azerbaijan’s international obligations and commitments, especially as the chair of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe.

Signed by:

Human Rights House Azerbaijan (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House in exile, Vilnius (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House Belgrade (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House Kiev (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House London (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House Sarajevo (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House Tbilisi (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House Oslo (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House Voronezh (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House Yerevan (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Human Rights House Zagreb (on behalf of the following NGOs):

The Rafto House in Bergen, Norway (on behalf of the following NGOs):

The House of the Helsinki Foundation For Human Rights, Poland (on behalf of the following NGOs):

Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center, Azerbaijan

Foundation “Multiethnic Resource Center for Civic Education Development”, Georgia

People in Need, Czech Republic

Public Movement Multinational, Georgia

Public Association for Assistance to Free Economy, Azerbaijan

Public Union of Democracy and Human Rights Resource Centre, Azerbaijan

This statement was originally posted on Aug 5, 2014 at http://humanrightshouse.org/Articles/20321.html