25 Jan 23 | Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Belarus, Belgium, Botswana, Burma, China, Cuba, Czech Republic, Denmark, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Index Index, Ireland, Laos, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Netherlands, News and features, Nicaragua, North Korea, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Switzerland, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, United States, Yemen

A major new global ranking index tracking the state of free expression published today (Wednesday, 25 January) by Index on Censorship sees the UK ranked as only “partially open” in every key area measured.

In the overall rankings, the UK fell below countries including Australia, Israel, Costa Rica, Chile, Jamaica and Japan. European neighbours such as Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Denmark also all rank higher than the UK.

The Index Index, developed by Index on Censorship and experts in machine learning and journalism at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), uses innovative machine learning techniques to map the free expression landscape across the globe, giving a country-by-country view of the state of free expression across academic, digital and media/press freedoms.

Key findings include:

-

The countries with the highest ranking (“open”) on the overall Index are clustered around western Europe and Australasia – Australia, Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland.

-

The UK and USA join countries such as Botswana, Czechia, Greece, Moldova, Panama, Romania, South Africa and Tunisia ranked as “partially open”.

-

The poorest performing countries across all metrics, ranked as “closed”, are Bahrain, Belarus, Burma/Myanmar, China, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Laos, Nicaragua, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

-

Countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates performed poorly in the Index Index but are embedded in key international mechanisms including G20 and the UN Security Council.

Ruth Anderson, Index on Censorship CEO, said:

“The launch of the new Index Index is a landmark moment in how we track freedom of expression in key areas across the world. Index on Censorship and the team at Liverpool John Moores University have developed a rankings system that provides a unique insight into the freedom of expression landscape in every country for which data is available.

“The findings of the pilot project are illuminating, surprising and concerning in equal measure. The United Kingdom ranking may well raise some eyebrows, though is not entirely unexpected. Index on Censorship’s recent work on issues as diverse as Chinese Communist Party influence in the art world through to the chilling effect of the UK Government’s Online Safety Bill all point to backward steps for a country that has long viewed itself as a bastion of freedom of expression.

“On a global scale, the Index Index shines a light once again on those countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates with considerable influence on international bodies and mechanisms – but with barely any protections for freedom of expression across the digital, academic and media spheres.”

Nik Williams, Index on Censorship policy and campaigns officer, said:

“With global threats to free expression growing, developing an accurate country-by-country view of threats to academic, digital and media freedom is the first necessary step towards identifying what needs to change. With gaps in current data sets, it is hoped that future ‘Index Index’ rankings will have further country-level data that can be verified and shared with partners and policy-makers.

“As the ‘Index Index’ grows and develops beyond this pilot year, it will not only map threats to free expression but also where we need to focus our efforts to ensure that academics, artists, writers, journalists, campaigners and civil society do not suffer in silence.”

Steve Harrison, LJMU senior lecturer in journalism, said:

“Journalists need credible and authoritative sources of information to counter the glut of dis-information and downright untruths which we’re being bombarded with these days. The Index Index is one such source, and LJMU is proud to have played our part in developing it.

“We hope it becomes a useful tool for journalists investigating censorship, as well as a learning resource for students. Journalism has been defined as providing information someone, somewhere wants suppressed – the Index Index goes some way to living up to that definition.”

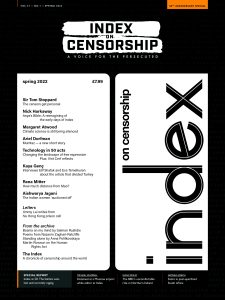

14 Apr 22 | News and features, Russia, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022 Extras

The story of Index on Censorship is steeped in the romance and myth of the Cold War.

In one version of the narrative, it is a tale that brings together courageous young dissidents battling a totalitarian regime and liberal Western intellectuals desperate to help – both groups united in their respect for enlightenment values.

In another, it is just one colourful episode in a fight to the death between two superpower ideologies, where the world of letters found itself at the centre of a propaganda war.

Both versions are true.

It is undeniably the case that Index was founded during the Cold War by a group of intellectuals blooded in cultural diplomacy. Western governments (and intelligence services) were keen to demonstrate that the life of the mind could truly flourish only where Western values of democracy and free speech held sway.

But in all the words written over the years about how Index came to be, it is important not to forget the people at the heart of it all: the dissidents themselves, living the daily reality of censorship, repression and potential death.

The story really began not in 1972, with the first publication of this magazine, but with a letter to The Times and the French paper Le Monde on 13 January 1968. This Appeal to World Public Opinion was signed by Larisa Bogoraz Daniel, a veteran dissident, and Pavel Litvinov, a young physics teacher who had been drawn into the fragile opposition movement during the celebrated show-trial of intellectuals Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel (Larisa’s husband) in February 1966. This is now generally accepted as being the beginning of the modern Soviet dissident movement.

The letter itself was written in response to the Trial of Four in January 1968, which saw two students, Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg, sentenced to five years’ hard labour for the production of anti-communist literature.

The other two defendants were Alexey Dobrovolsky, who pleaded guilty and co-operated with the prosecution, and a typist, Vera Lashkova.

Ginzburg later became a prominent dissident and lived in exile in Paris, Galanskov died in a labour camp in 1972 and Dobrovolsky was sent to a psychiatric hospital. Lashkova’s fate is unclear.

The letter was the first of its kind, appealing to the Soviet people and the outside world rather than directly to the authorities. “We appeal to everyone in whom conscience is alive and who has sufficient courage… Citizens of our country, this trial is a stain on the honour of our state and on the conscience of every one of us.”

The letter went on to evoke the shadow of Joseph Stalin’s show-trials in the 1930s and ended: “We pass this appeal to the Western progressive press and ask for it to be published and broadcast by radio as soon as possible – we are not sending this request to Soviet newspapers because that is hopeless.”

The trial took place in a courthouse packed with Kremlin supporters, while protesters outside endured temperatures of 50 degrees below zero.

The poet Stephen Spender responded to the letter by organising a telegram of support from 16 prominent artists and intellectuals, including philosopher Bertrand Russell, poet WH Auden, composer Igor Stravinsky and novelists JB Priestley and Mary McCarthy.

It took eight months for Litvinov to respond, as he had heard the words of support only on the radio and was waiting for the official telegram to arrive. It never did.

On 8 August 1968, the young dissident outlined a bold plan for support in the West for what he called “the democratic movement in the USSR”. He proposed a committee made up of “universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities” to be taken not just from the USA and western Europe but also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, ultimately, from the Soviet bloc itself. Litvinov later wrote an account in Index explaining how he had typed the letter and given it to Dutch journalist and human rights activist Karel van Het Reve, who smuggled it out of the country to Amsterdam the next day. Two weeks later, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring.

On 25 August 1968, Litvinov and Bogoraz Daniel joined six others in Red Square to demonstrate against the invasion. It was an extraordinary act of courage. They sat down and unfurled homemade banners with slogans that included “We are Losing Our Friends”, “Long Live a Free and Independent Czechoslovakia”, “Shame on Occupiers!” and “For Your Freedom and Ours”.

The activists were immediately arrested and most received sentences of prison or exile, while two were sent to psychiatric hospitals.

Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright and first president of the Czech Republic, later said in a Novaya Gazeta article: “For the citizens of Czechoslovakia, these people became the conscience of the Soviet Union, whose leadership without hesitation undertook a despicable military attack on a sovereign state and ally.”

When Ginzburg died in 2002, novelist Zinovy Zinik used his Guardian obituary to sound a note of caution. Ginzburg, he wrote, was “a nostalgic figure of modern times, part of the Western myth of the Russia of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, when literature, the word, played a crucial part in political change”.

Speaking 20 years later, Zinik told Index he did not even like the English word “dissident”, which failed to capture the true complexity of the opposition to the Soviet regime. “The Russian word used before ‘dissidents’ invaded the language was ‘inakomyslyashchiye’ – it is an archaic word but was adopted into conversational vocabulary. The correct translation would be ‘holders of heterodox views’.”

It’s perhaps understandable that the archaic Russian word didn’t catch on, but his point is instructive.

As Zinik warned, it is all too easy to romanticise this era and see it through a Western lens. The Appeal to World Public Opinion was not important because it led to the founding of Index. The letter was important because it internationalised the struggle of the Soviet dissident movement.

As Litvinov later wrote in Index: “Only a few people understood at the time that these individual protests were becoming a part of a movement which the Soviet authorities would never be able to eradicate.” Index was a consequence of Litvinov’s appeal; it was not the point of the exercise and there was no mention of a magazine in the early correspondence.

The original idea was to set up an organisation, Writers and Scholars International, to give support to the dissidents. It was only with the appointment of Michael Scammell in 1971 that the idea emerged to establish a magazine to publish and promote the work of dissidents around the world.

Spender and his great friend and co-collaborator, the Oxford philosopher Stuart Hampshire, were still reeling from revelations about CIA funding of their previous magazine, Encounter.

“I knew that [they]… had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line,” Scammell wrote in Index in 1981.

Speaking recently from his home in New York, Scammell told me: “I understood Pavel Litvinov’s leanings here. He understood that a magazine that was impartial would stand a better chance of making an impression in the Soviet Union than if it could just be waved away as another CIA project.”

Philip Spender, the poet’s nephew, who worked for many years at Index, agreed: “Pavel Litvinov was the seed from which Index grew… He always said it shouldn’t be anti-communist or anti-Soviet. The point wasn’t this or that ideology. Index was never pro any ideology.”

It has been suggested that Index did not mark quite such a clean break – it was set up by the same Cold Warriors and susceptible to the same CIA influence. In her exhaustive examination of the cultural Cold War, Who Paid the Piper, journalist Frances Stonor Saunders claimed Index was set up with a “substantial grant” from the Ford Foundation, which had long been linked to the CIA.

In fact, the Ford funding came later, but it lasted for two decades and raises serious questions about what its backers thought Index was for.

Scammell now recognises that the CIA was playing a sophisticated game at the time. “On one level this is probably heresy to say so, but one must applaud the skills of the CIA. I mean, they had that money all over the place. So, I would get the Ford Foundation grant, let’s say, and it never ever occurred to me that that money itself might have come from the CIA.”

He added: “I would not have taken any money that was labelled CIA, but I think they were incredibly smart.”

By the time the magazine appeared in spring 1972, it had come a long way from its origins in the Soviet opposition movement. It did reproduce two short works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and poetry by dissident Natalya Gorbanevskaya (a participant in the 1968 Red Square demonstration, who had been released from a psychiatric hospital in February of that year). But it also contained pieces about Bangladesh, Brazil, Greece, Portugal and Yugoslavia.

Philip Spender said it was important to understand the context of the times: “There was a lot of repression in the world in the early ’70s. There was the imprisonment of writers in the Soviet Union, but also Greece, Spain and Portugal. There was also apartheid. There was a coup in Chile in 1973, which rounded up dissidents. Brazil was not a friendly place.”

He said Index thought of itself as the literary version of Amnesty International. “It wasn’t a political stance, it was a non-political stance against the use of force.”

The first edition of the magazine opened with an essay by Stephen Spender, With Concern for Those Not Free. He asked each reader of the article to say to themselves: “If a writer whose works are banned wishes to be published and if I am in a position to help him to be published, then to refuse to give help is for me to support censorship.”

He ended the essay in the hope that Index would act as part of an answer to the appeal “from those who are censored, banned or imprisoned to consider their case as our own”.

Since Index was founded, the Berlin Wall has fallen and apartheid has been dismantled. We have witnessed the “war on terror”, the rise of Russian president Vladimir Putin and the emergence of China as a world superpower.

And yet, if it is not too grand or presumptuous, the role of the magazine remains unchanged – to consider the case of the dissident writer as our own.

![]() SUBSCRIBE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]