14 Mar 14 | Africa, News and features, Uganda

Hundreds of Ugandans took to the streets in support of the government’s proposed anti-homosexuality bill in 2009 (Image: Edward Echwalu/Demotix)

A petition has been filed to the Constitutional Court of Uganda seeking to repeal the Anti Homosexuality Act 2014, on the grounds that it is “draconian” and “unconstitutional”.

The petitioners — MP Fox Odoi, Joe Oloka Onyango, Andrew Mwenda, Ogenga Latigo, Paul Semugooma, Jacqueline Kasha, Julian Onziema, Frank Mugisha and two civil society organisations — are challenging sections 1, 2 and 4 of the recently passed anti-gay law, which criminalise homosexual activity, between consenting adults in private. They argue these sections are in contravention of the right to privacy and equality before the law without discrimination, guaranteed under the Ugandan constitution. They also claim the that bill was passed without quorum in parliament, despite Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi informing the speaker of this — also an unconstitutional act.

Addressing the media after filing the petition, Odoi vowed to fight for the rights of gay people even if it meant him losing support from his constituency. “I would rather lose my seat in parliament than leave the rights of the minorities to be trampled upon. I don’t fear losing an election, but I fear living in a society that has no room for minorities,” he said. “A country that cannot tolerate minority groups like gays should never claim to be democratic, lawful and pro-people,” he added.

The petitioners have highlighted several parts of the new law that they believe to be unconstitutional. They argue that life sentence for homosexuality is in contravention of the freedom from cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment, while the section subjecting persons charged with “aggravated homosexuality” to compulsory HIV test is inconsistent with a number of articles in the constitution.

The petition also argues that through banning aiding, abetting, counselling, procuring and promotion of homosexuality, the law is creating overly broad offences. Additionally, the group state that it’s wrong for the act to penalise legitimate debate on homosexuality, as well as professional counsel, HIV-related service provision and access to general health services for gay people.

Petitioner Ogenga Latigo, former leader of the opposition in parliament, questioned the competence of the speaker of parliament who passed the law without quorum. Speaker Rebecca Kadaga has in the past been vocal about her disdain for homosexuals, and wanted this law passed before the end of 2012 as a “Christmas gift” to Ugandans. “The speaker’s position should always remain neutral while tabling issues in parliament, but our speaker went on and enforced her views on all MPs; the speaker never followed the procedures that govern the passing of laws in parliament because of her homophobic beliefs,” he said.

The group argues that since the law was enacted, there has been an increase in the number of violent attacks on gay people. In other instances, they say, those suspected or known to be gay have been evicted from their apartments by homophobic landlords.

Odoi, who authored a minority report against the bill before it was passed by parliament, is optimistic that the petition will succeed, if the case is handled by unbiased judges. “We want court to declare the law unconstitutional, null and void and cease to be a binding law, thus give a chance to homosexuals to enjoy their rights and freedoms,” he asserted.

This article was posted on March 14 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Mar 14 | Africa, News and features, Uganda

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Uganda’s recently passed Anti-Pornography Act 2014 is believed to have led to targeting of women wearing mini-skirts, prompting the cabinet to review the law.

Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi told parliament recently that it is not the duty of the public but the police to implement the law: “The law is not about the length of one’s dress or skirt. As cabinet, we are going to look at the act again.”

The law, assented to by President Yoweri Museveni on 6 February this year, creates and defines the offence of pornography and its prohibition. It bans anyone from producing, trafficking, publishing, broadcasting, procuring, importing exporting or abetting any form of pornography.

Nowhere in the law is a ban on mini-skirts mentioned. The prime minister said that the term “indecent” as defined in the act to mean “non conformity with generally accepted standards” is too broad and varies from one person to another. “It’s very important that the law is clear and specific. I request the public not to take the law in their hands. It’s criminal, especially to women; they must be fully protected, and we shall protect them,” he said.

Initially, the bill proposed the prohibition of types of dress that exposed different body parts like breasts, thighs, genitalia and buttocks, but that clause was deleted before it was enacted into law. The law that was ultimately passed targets media organisations, Internet Service Providers (ISP’s), the entertainment and leisure industry and others putting what is deemed pornographic material into the public domain. Despite this, many women are afraid of the consequences of the law.

The apparent misunderstanding of the law by the public has generally been blamed on Ethics and Integrity Minister Simon Lokodo, who has suggested that it will ultimately help in the fight against indecent dressing by women. He has openly stated that “if a woman is dressed in attire that irritates the mind and excites other people of the opposite sex, you are dressed in wrong attire, so please you should hurry up and go home and change.” He maintains that women should “dress decently” because “men are so weak that if they saw an indecently dressed woman, they would just jump on her”. It should be noted that this minister is a former priest of the Catholic Church.

The act defines pornography as any cultural practice, radio or television programme, writing, publication, advertisement, broadcast, upload on the internet, display, entertainment, music, dance, picture, audio or video recording, show, exhibition or any combination of these that depicts a person engaged in explicit sexual activities or conduct; sexual parts of a person; erotic behaviour intended to cause sexual excitement or any indecent act or behaviour tending to corrupt morals.

The act also proposes setting up a Pornography Control Committee to, among other things, ensure that perpetrators of pornography are apprehended and prosecuted, and to collect and destroy all pornographic materials.

Ruth Ojiambo Othieno, the Executive Director of Isis-Women’s International Cross Cultural Exchange said she was disappointed that the law is targeting women and their bodies.

Miria Matembe, a woman’s activist and former ethics minister argues that the law is very vague and compares it to former President Idi Amin’s directive that women should not wear skirts and dresses more than three inches above the knee.

In a statement, police spokesperson Judith Nabakooba warned that if one suspects a person to be indecently dressed, they should report the matter to police but not take the law into their own hands. “Anyone found participating in mob justice of undressing people and are caught will be dealt with accordingly,” she said.

This article was posted on March 10, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

04 Mar 14 | Africa, News and features, Uganda

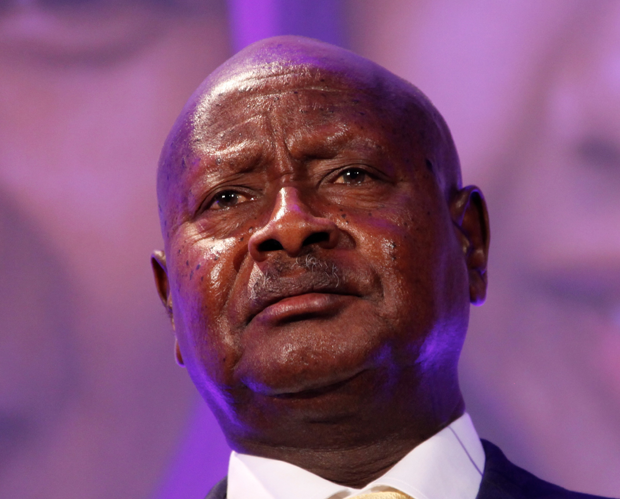

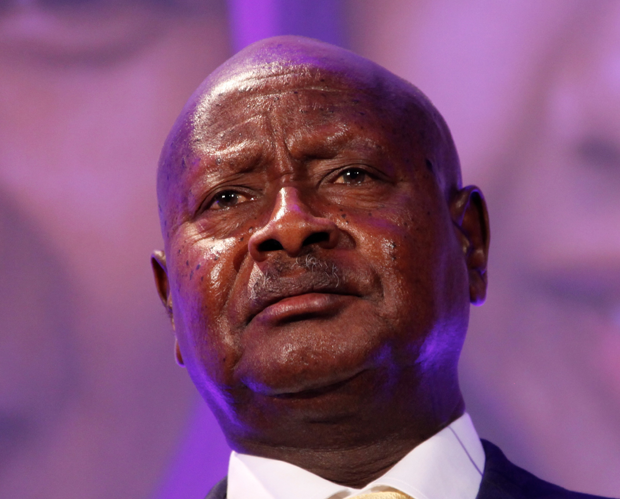

Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni (Photo: Wikipedia)

President Yoweri Museveni signed Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality bill into law on 24 February, and the fallout has already started. The World Bank has cancelled a $90 million loan to the country, European Union countries are threatening to withdraw aid, and the United States is reviewing its cooperation with Uganda. President Museveni has hit back, saying Uganda would raise its own money to fund its development projects. The US, which was the first voice its discontent, was told off: “Our relationship with the US was not based on homosexuality.” David Bahati, the MP who introduced the bill, said in an interview that the west is imposing social imperialism on Uganda, a thing they are not ready to accept.

“I will work with the Russians,” Museveni said.

So the president feels that even without the west, Uganda has development partners that it can still rely on. Considering he was not supportive of the so-called Bahati bill in its initial stages, Museveni’s last-minute change of heart is baffling.

The law stipulates that punishment for homosexuals will be a life jail sentence, while those who “attempt” to engage in homosexual acts face seven years in prison. The law also targets journalists and others seen to participate in “production, procuring, marketing, broadcasting, disseminating, publishing of pornographic materials for purposes of promoting homosexuality”. It even attempts to reach beyond the country’s borders, implong that Uganda will have to ask countries where gay Ugandans live to extradite them so that they can face the law.

Public opinion goes both ways. Many are happy that the president is standing firm against “the west” and the perceived scheme of promoting homosexuality in Uganda and Africa at large. Others claim that the president signed this law to achieve cheap popularity with the 2016 elections around the corner. It is also claimed that President Museveni is just playing his usual political games. When the anti-homosexuality bill was passed by parliament early this year, one of the president’s legal brains, Fox Odoi, publicly stated that if the president ever assents to this law, he would challenge it in court.

Odoi has now teamed up with Ugandan journalist Andrew Mwenda to take the case to the constitutional court. It is alleged that this was Museveni’s game plan: sign the law, annoy the west and appease the locals, and then have his henchmen challenge this law in court and make sure it remains there forever. In this case, the west will soften their stance towards Museveni, and the locals will be told to be patient and leave the legal process to take its course. In that case, he will have killed two birds with one stone, and would go for the 2016 elections with both the west and the locals in his pockets.

Civil society has also been critical, not because the anti-homosexuality law is unnecessary per se, but they have questioned whether homosexuality is the biggest problem Uganda faces today, and warrants such urgency. With high youth unemployment, squalid conditions in health facilities and theft of public funds in government institutions, they believe priorities should lie somewhere else other than “fixing” homosexuality.

“The timing for the assenting to this law by the president is meant to divert the country’s attention from the discussion on the deployment of Ugandan forces in South Sudan and our mandate there. This law is very diversionary, and it is unfortunate that Ugandans have swallowed the president’s bait,” said Godber Tumushabe, a renowned civil society activist.

Opposition leader Kizza Besigye has criticised the new law, saying that homosexuality was not “foreign” and that the issue was being used to divert attention from domestic problems. “Homosexuality is as Ugandan as any other behaviour, it has nothing to do with the foreigners,” said Besigye. He accused the government of having “ulterior motives” and using the issue to divert attention from other issues, including Uganda’s military backing of neighbouring South Sudan’s government against rebel forces.

Sweden’s Finance Minister Anders Borg, who visited the country a day after the signing of the law, said it “presents an economic risk for Uganda”.

But Besigye accused them of double standards, saying that their cutting of aid over gay rights alone was “misguided”:

”They should have cut aid a long time ago because of more fundamental rights, our rights have been violated with impunity and they kept silent,” he said.

This article was posted on March 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Nov 13 | News and features, Uganda

Hundreds of Ugandans took to the streets in support of the government’s proposed anti-homosexuality bill in 2009 (Image: Edward Echwalu/Demotix)

The Ugandan government’s position on homosexuality is considered one of the harshest in the world. The proposed Anti-Homosexuality Bill, seeks to, among other things, broaden the criminalisation of homosexuality so that Ugandans who engage in same-sex relations abroad can be extradited to Uganda and charged. Originally, some of the provisions in the law called for death penalties or life sentences for those convicted as homosexuals. It has since been amended to remove the proposal of death penalties, but the life sentences remain.

A special motion to introduce the legislation was passed only a month after a two-day conference where three American Christians asserted that homosexuality is a direct threat to the cohesion of African families. Indeed, the church — both Anglican and Catholic — plays a big role in shaping the government’s tough stance on homosexuality. New Pentecostal churches are also fuelling the anti-gay message, with firebrand crusaders like Pastor Martin Sempa at the forefront.

Together, the state and the church accuse the gay community of recruiting young people in schools. There have also been claims that gay people are recording sex videos with young Ugandans that they then sell abroad. It is said that young people are lured into this with promises of financial gains. Sixty-five-year-old Brit Bernard Randall is facing trial for engaging in gay sex, and for possession of videos of him engaging in gay sex.

Anti-gay legislation has been in place in Uganda for some time. Laws prohibiting same-sex sexual acts were first introduced under British colonial rule in the 19th century, and those were enshrined in the Penal Code Act 1950. Section 146 states that “any person who attempts to commit any of the offences specified in section 145 commits a felony and is liable to imprisonment for seven years.” On 29th September 2005, President Museveni also signed a constitutional amendment prohibiting same-sex marriages.

But the anti-gay bill is not the only story on this topic to come out of Uganda in recent times. In 2004, the Uganda Broadcasting Council fined Radio Simba $1,000 for hosting homosexuals on one of its shows, and the radio station was forced to make a public apology. In January 2011, LGBT activist David Kato was killed. Kato, together with Patience Onziema and Kasha Jacqueline, had successfully sued a Ugandan paper the Rolling Stone and its Managing Editor Giles Muhame. The paper had published their full names and photos, as well as those of a number of other allegedly gay people and called for the lynching of all homosexuals. The court issued a permanent injunction preventing the paper and the editor from publishing the identities of any other homosexuals. Kato’s murderer, Enoch Nsubuga, was handed down a 30-year prison sentence.

On 3 October 2011, a local human rights and LGBT activist challenged a part of the Equal Opportunities Commission Act in the Constitutional Court. Section 15(6)(d) prevents the Equal Opportunities Commission from investigating “any matter involving behaviour which is considered to be (i) immoral and socially harmful, or (ii) unacceptable by the majority of the cultural and social communities in Uganda.” The petitioner argued that this clause is discriminatory and violates the constitutional rights of minority populations. A decision has not yet been made on the petition.

The bill has, however, caused the most outrage. The Ugandan government and the evangelicals faced immense international criticism, and the bill was met with protests from LGBT, human rights and civil society groups. Countries including Sweden even threatened to stop their aid to Uganda in protest.

In response to the attention, the bill was revised to drop the death penalty, and President Yoweri Museveni formed a commission to investigate the possible repercussions of passing it. The Speaker of the Ugandan parliament promised in November 2012 the bill would pass by the end of the year as a Christmas gift for the group that supported it. It is, for now, still on hold. But while the Ugandan government has toned down its rhetoric against the gay community lately — this is believed to be due to international pressure — the persecution of gay people in the country persists.

This article was originally posted on 29 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org