Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

Statement: Egyptian authorities must stop their attacks on media freedom from Article 19, the Committee to Project Journalists, Index on Censorship and Reporters Without Borders. PDF: Arabic

The wording of proposed anti-terrorism legislation in Egypt has been leaked, sparking concern amongst opposition activists over upcoming government censorship. The legislation could allow for social networking sites such as Facebook to be barred, if they are deemed to be endangering public order.

Al Sherooq, an Arabic-language daily newspaper, reported on the news, stating that ant-terrorism legislation “for the first time includes new laws which guarantee control over ‘terrorism’ crimes in a comprehensive manner, starting with the monitoring of Facebook and the Internet, in order of them not to be used for terrorism purposes”.

According to Al Sherooq, the document is now being circulated around Cabinet for approval, and will build upon the country’s new constitution, recently approved with 98% support. The constitution includes provisions for emergency legislation at points of crisis.

The law is ostensibly designed to improve the ability of the military government to provide security, against a backdrop of rising violence and terrorism attacks. It lays out proposed punishments for those involved with designated terrorism offences, and for inciting violence. It would also establish a special prosecution unit and criminal court focused on convicting terrorists.

The leaked document also shows how broadly terrorism will be defined, as it includes “use of threat, violence, or intimidation to breach public order, to violate security, to endanger people”. It is also defined “as acts of violence, threat, intimidation that obstruct public authorities or government, as well as implementation of the constitution”.

Commentators were quick to note that Facebook would be high on the list of potentially barred sites, as it is frequently used by members of the Muslim Brotherhood and other opposition groups, to co-ordinate protests.

YouTube has also recently been used by jihadist groups; one video posted recently showed a masked man firing a rocket at a freight ship passing through the Suez.

“What worries me most is the level of popular support for these laws,” said Mai El-Sadany, an Egyptian-American rights activist. “If you look at how much support the referendum won, and also recent polling about the terrorism laws, there is definitely a sense that people want peace and stability.”

“But Egypt now is like America after 9/11,” she added. “People are believing the lies the government are telling them. There is the same sentiment of fear, with a legitimate basis, but human rights abuses and loss of civil liberty are a possibility.”

Since Morsi’s deposal in July 2013, terrorists group have attempteed to kill the interior minister, bombed the National Security heaquarters in Mansoura and Cairo, shot down a military helicopter in the Sinai Peninsula, fired a rocket at a passing freighter ship in the Suez canal, and assassinated a senior security official. A group calling itself Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (translated as “Supporter of Jerusalem”) has claimed responsibility for most of the attacks.

The constitutional referendum result has already been used by the regime to demonstrate Sisi’s credibility. However, critics say that any media channels supportive of the opposing Islamist agenda were all shut down after the military coup, and that voters suggesting they might vote against the referendum were threatened by government officials, suggesting Sisi’s mandate may be questionable.

There was also a notable lack of support for the referendum in the south of Egypt as opposed to the north.

Recent polling data suggests that the terrorism legislation could be popular, with 65% of Egyptians having heard about possible new laws, and 62% approving of it. Polling results also showed significantly more support amongst degree-educated Egyptians as opposed to less educated people.

An earlier form of the legislation has already been used to arrest dozens of activists and journalists, including several employees of Al Jazeera. Viewership of the Qatar-based network has reduced as support for the Muslim Brotherhood has declined. The Muslim Brotherhood’s activities in Egypt have been funded by Gulf states.

It is thought the new definition of terrorism could be used to indict the detained Al Jazeera journalists. To date, it has been unclear under what legislation they could be prosecuted.

Political analyst and blogger Ramy Yaccoub, from Cairo, criticised the leaked legislation voraciously via his Twitter account: “This is becoming ridiculous,” he tweeted. This was followed by: “There needs to be an international treaty that governs the sanctity of private communication.”

There is currently no agreed timeframe for the Egyptian legislative process, so it is unclear how long it will take for the laws to come into force.

The wording of the legislation has been translated into English and is available here.

This article was posted on 3 Feb 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

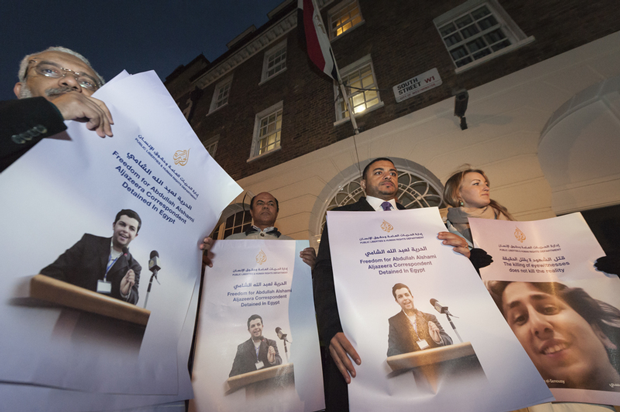

In November 2013, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ UK and Ireland), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and the Aljazeera Media Network organised a show of solidarity for the journalists who have been detained, injured or killed in Egypt. (Photo: Lee Thomas / Demotix)

Statement: Egyptian authorities must stop their attacks on media freedom from Article 19, the Committee to Project Journalists, Index on Censorship and Reporters Without Borders

Twenty journalists working for the Al Jazeera TV network will stand trial in Egypt on charges of spreading false news that harms national security and assisting or joining a terrorist cell.

Sixteen of the defendants are Egyptian nationals while four are foreigners: a Dutch national, two Britons and Australian Peter Greste, a former BBC Correspondent. The chief prosecutor’s office released a statement on Wednesday saying that several of the defendants were already in custody; the rest will be tried in absentia.The names of the defendants, however, were not revealed. The case marks the first time journalists in Egypt have faced trial on terrorism-related charges, drawing condemnation from rights groups and fueling fears of a worsening crackdown on press freedom in Egypt .

“This is an insult to the law,” said Gamal Eid, a rights lawyer and head of the Arab Network for Human Rights Information. “If there is justice in Egypt , courts would not be used to settle political scores”, he added.

In December, the government designated the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization. It has since widened its heavy-handed crackdown on Brotherhood supporters, targeting pro-democracy activists, journalists and anyone considered remotely sympathetic to the outlawed Islamist group.

In a move seen by rights advocates as a blow to freedom of expression, most Islamist channels were shut down by the Egyptian authorities almost immediately after Islamist President Mohamed Morsi was toppled in July. The Qatar-based Al-Jazeera is one of the few remaining networks perceived by the authorities as sympathetic to Morsi and the Brotherhood.

Once praised by Egyptians as the “voice of the people” for its coverage before and during the 2011 mass protests that led to the removal of autocrat Hosni Mubarak from power, Al Jazeera has since seen its popularity dwindle in Egypt. Since Morsi’s ouster by military-backed protests in July, Qatar has been the target of media and popular wrath because of its backing for the Brotherhood. Allegations by the state controlled and private pro-government media that Qatar was”plotting to undermine Egypt’s stability” has inflamed public anger against the Qatar-funded network, prompting physical and verbal attacks by Egyptians on the streets on journalists suspected of working for Al Jazeera.

The Al Jazeera Arabic service and its Egyptian affiliate Mubasher Misr were the initial targets of a government crackdown on the network and have had their offices ransacked by security forces a number of times. In recent months however, the crackdown on the network has escalated, targeting journalists working for the Al Jazeera English service as well despite a general perception among Egyptians that the latter is “more balanced and fair” in its coverage of the political crisis in Egypt.

The Al Jazeera network has denied any biases on its part and has repeatedly called on Egypt to release its detained staff. According to a statement released by Al Jazeera on Wednesday, the allegations made by Egypt’s chief prosecutor against its journalists are “absurd, baseless and false.”

“This is a challenge to free speech, to the right of journalists to report on all aspects of events, and to the right of people to know what is going on.” the statement said.

Three members of an Al Jazeera English (AJE) TV crew were arrested in a December police raid on their makeshift studio in a Cairo luxury hotel and have remained in custody for a month without charge. Both Canadian-Egyptian journalist Mohamed Fahmy — the channel’s bureau chief –and producer Baher Mohamed have been kept in solitary confinement in the Scorpion high security prison reserved for suspected terrorists and dangerous criminals. An investigator in the case who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the press said Fahmy was an alleged member of a terror group and had been fabricating news to tarnish Egypt’s image abroad.

Earlier this week, Fahmy’s brother, Sherif, complained that treatment of his brother had taken a turn for the worse and that prison guards had taken away his watch, blanket and writing materials.

Peter Greste, the only non-Egyptian member of the AJE team has meanwhile, been held at Torah Prison in slightly better conditions. In a letter smuggled out of his prison cell earlier this month, Greste recounted the ordeal of his Egyptian detained colleagues, saying “Fahmy has been denied the hospital treatment he badly needs for a shoulder injury he sustained shortly before our arrest. Both men spend 24 hours a day in their mosquito-infested cells, sleeping on the floor with no books or writing materials to break the soul-destroying tedium.”

Al Jazeera Arabic correspondent Abdullah El Shamy, another defendant in the case, has meanwhile been in jail for 22 weeks. He was arrested on August 14 while covering the forced dispersal by security forces of a pro-Morsi sit-in and has been charged with inciting violence, assaulting police officers and disturbing public order. El Shamy began a hunger strike ten days ago to protest his continued detention. In a letter leaked from his cell at Torah Prison and posted on Facebook by his brother, El Shamy insisted he was innocent of all charges. He remains defiant however, saying that “nothing will break my will or dignity.” On Thursday, his detention was extended for 45 days pending further investigations . His brother Mohamed El Shamy, a photojournalist, was arrested in Cairo on Tuesday while taking photos at a pro-Muslim Brotherhood protest. He was released a few hours later.

Al Jazeera Mubashir cameraman Mohamed Badr is also behind bars. He was arrested while covering clashes between Muslim Brotherhood supporters and security forces in July and has remained in custody since.

The case of the Al Jazeera journalists sends a chilling message to journalists that there is a high price to pay for giving the Muslim Brotherhood a voice. A journalist working for a private pro-government Arabic daily sarcastly told Index that there is only one side to the story in Egypt: the government line. Mosa’ab El Shamy, a photojournalist whose brother is one of the defendants in the Al Jazeera case posted an article this week on the website Buzzfeed, humorously titled: If you want to get arrested in Egypt, work as a journalist.

In truth though, the case is no laughing matter. National Public Radio’s Cairo Correspondent Leila Fadel said it shows just how far Egypt has backslid on the goals of the January 2011 uprising when pro-democracy protesters had demanded greater freedom of expression. Today, violations against press freedoms in Egypt are the worst in decades, according to the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists. Sadly, it does not look like the situation for journalists in Egypt will improve anytime soon.

In the meantime the fate of the Al Jazeera journalists hangs in the balance.

This article was posted on 31 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Leading international media freedom and human rights organisations call on the EU and US to demand Egypt’s authorities drop charges against Al-Jazeera journalists and release those under arrest

Article 19, the Committee to Protect Journalists, Index on Censorship and Reporters Without Borders today said the Egyptian authorities must stop their attacks on media freedom and freedom of expression. The deteriorating environment for journalists to operate safely and report freely is of grave concern. The deliberate chilling of media freedom and free speech through arrests and criminalisation of legitimate journalism has all the hallmarks of the authoritarian Egypt of the Mubarak era.

The organisations call on the leaders of the European Union and the US to demand that Egypt’s authorities immediately release the Al-Jazeera journalists and end their clamp-down on media freedom, free speech and freedom of assembly without delay. The EU and US must support all those standing up for democracy, human rights and media freedom in Egypt.

Egyptian prosecutors have said that 20 journalists face charges though only 8 are currently under arrest. Four of these are believed to be foreigners and the other 12 said to be Egyptians.

Thomas Hughes, Executive Director, Article 19

Joel Simon, Executive Director, Committee to Protect Journalists

Kirsty Hughes, Chief Executive, Index on Censorship

Christophe Deloire, Secretaire Général, Reporters Without Borders

Press Contacts

Article 19: Ayden Peach, 07973911993

Committee to Protect Journalists: Samantha Libby, [email protected] / +1 212 300 9032 ext 124

Index on Censorship: Padraig Reidy, [email protected] / 0207 260 2660

Reporters Without Borders: Isabelle Gourmelon, [email protected] / +33 01 44 83 84 56

Supporters of General Sisi in December 2013 (Photo: Sharron Ward / Demotix)

National Police Day, 25 January 2011. Years of police brutality is being challenged by activists in Tahrir Square. Volleys of tear gas mark the beginning of the Egyptian revolution, even if nobody knows it yet.

“The police were in control of everything that day,” journalist Muhammad Mansour remembers. “But it was a sign. I remember feeling like that day was a test for the police…it was a difficult fight.”

But three years on and Egypt looks a very different place. On Friday at least 64 people were killed nationwide – most of them with live ammunition – and 1,076 people arrested, according to official figures. Informal counts put the number of deaths closer to 100.

While revolutionary protesters were shot dead in downtown Cairo, including an April 6 activist – Sayed Wezza – who campaigned for the Tamarod movement against former Islamist President Mohamed Morsi, over 40 Muslim Brotherhood supporters were gunned down in the north-east of the capital. In both cases, authorities allegedly resorted to using near-immediate lethal force to disperse protests and, activists claim, silence dissent.

One revolutionary march from Mostafa Mahmoud square was dispersed quickly, another outside the Journalists’ Syndicate faced a similar reaction. In both cases, police reacted minutes after marches started moving. A statement from an April 6 Youth Movement organiser, texted minutes after the dispersal started, alleged the police had used live ammunition to disperse peaceful protests. “This is not the Egypt we are looking for,” it said.

“We didn’t even reach three blocks from the syndicate before we came under attack,” Revolutionary Socialist activist Tarek Shalaby says. After the tear gas started, he ran into a side-street as police vans hurtled round corners firing off tear gas and bullets. Shalaby then picked up a poster of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and got out. Not far from the clashes, Shalaby was then questioned by a Sisi supporter who was keen to know why his poster of the general was ripped.

National Police Day was once a stage-managed celebration of state authority. This year’s 25 January felt like that and more. Egyptians poured into Tahrir Square to the ubiquitous sounds of pro-army anthem ‘Teslam al-Ayadi.’ Crowds roared as military helicopters breezed over rooftops dropping Egyptian flags and vouchers for basic goods. For many, it was a stage-managed endorsement of General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s expected bid for the presidency – but one a majority of Egyptians wholeheartedly support.

While police attacked revolutionary and Brotherhood protests, the Saturday celebrations also revealed a street-level willingness to act side by side with the police.

It’s a role encouraged by state and independent media, Shalaby claims, referring to calls by Egyptian news channels for members of the public to citizen’s arrest potential Brotherhood supporters, or people looking to disrupt the day. Given Egypt’s currently hyper-nationalist state narrative, that leaves activists, Brotherhood members as well as journalists and foreigners privy to abuses.

An Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE) report recorded 36 violations against journalists and photojournalists on January 25. Vigilante justice, and impunity for those carrying it out, is a growing problem.

“I was interviewing the ‘Bride of Sisi’, as she called herself, when a crowd gathered around me and another journalist and accused us of working for a ‘terrorist’ news channel,” journalist Nadine Marroushi wrote in a London Review of Books blog. While interviewing inside the square, Marroushi and Daily News Egypt journalist Basil al-Dabh were accused of working for Al-Jazeera, insulted and physically assaulted. The police intervened and detained them for their own safety. “They took us away to a building just off the square and told us to hide there for an hour until the crowd calmed down.”

A video from a nearby street also showed a police officer telling a MBC Egypt camera camera to “move that camera…or I’ll tell the crowds you’re from Al-Jazeera.” The Qatari broadcaster has become deeply unpopular with many Egyptians, seen as one arm of the Muslim Brotherhood, itself identified as a terrorist organization in late December. Five Al-Jazeera journalists are currently in prison on charges of spreading false news and membership of a terrorist organization.

In a separate incident Matthew Stender, who went down to Tahrir to photograph the celebrations, was assaulted after running over to see where two Spanish journalists were being mobbed. Stender in turn was attacked. This time the army intervened and held him in a nearby room for an hour. While the Spanish journalists looked “quite roughed up,” Stender says, two other Egyptian journalists also accused of working for Al-Jazeera showed signs of “substantial injuries… [one] had a gash in the back of his head.”

In the run-up to January 25 this year, interim President Adly Mansour declared the “end of the police state in Egypt”. Meanwhile a damning report by Amnesty International last week condemned post-Morsi “state violence unseen even during the first 18 days of the ‘January 25 Revolution’,” expressing concerns that authorities are “utilizing all branches of the state apparatus to trample on human rights and quash dissent.” And the growing trend of violent protest dispersals, politicized detentions and home arrests suggest that Egypt is actually witnessing a return to old practices, only today they are dressed up in a fresh narrative indelibly stained red, white and black.

This article was published 0n 27 January at www.indexoncensorship.org