15 Jun 20 | China, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”113563″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]An extraordinary event in the history of not just Hong Kong but of the world took place exactly one year ago. A massive crowd, which according to some estimates was around two million strong, marched through the streets of the most cosmopolitan city on the China coast to call for the withdrawal of a proposed extradition bill that many felt would undermine the rule of law in Hong Kong. They also took action to express their anger at the brutality police had shown in dealing with a protest a few days before. And they demonstrated to show, more generally, that they were concerned that key features of local life that made the city different from its mainland neighbours, including greater freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, were under threat.

The marchers marched because they felt that the Chinese Communist Party leadership was failing to respect the second two words in the “One Country, Two System” framework that was supposed to structure relations between Beijing and Hong Kong for the first 50 years after the 1997 Handover that changed the latter from a British colony to a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. Xi Jinping and company were failing to respect the promise that Hong Kong would enjoy a “high degree of autonomy” until 2047. The marchers marched because they felt that Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam, chosen through an election in which fewer than 2,000 local residents were eligible to vote, was aiding and abetting this process. She was, in fact, the one who was championing the hated extradition bill, which would allow activists to be taken over the border to stand trial on the mainland if Beijing wished this to happen.

What made the march extraordinary in world historical terms? Even in an era that is witnessing wave after wave of protest struggles, the size of the crowd was unusual. There are few if any examples of roughly a quarter of the members of a sizeable political community taking to the streets at once. Yet, as Hong Kong is home to fewer than eight million people, that is what happened on 16 June 2019.

To mark that anniversary, we are publishing an excerpt from the closing pages of Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, a work written by historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom, with contributions by the journalist Amy Hawkins. Published earlier this year by Columbia Global Reports, it places that massive mid-June march and related 2019 events into historical and comparative perspective.

Vigil – whose lead author has recently contributed both a short story and two commentaries to Index and spoke last year at an Index event on a panel with the Guardian’s Tania Branigan that focused on the 30th anniversary of Tiananmen – makes particularly fitting reading right now. This is because in recent weeks Beijing and its local allies have made their most disturbing moves yet to destroy what little is left of the “autonomy” Hong Kong was promised. Showing disrespect for the Chinese national anthem has been criminalised, for example; highly respected figures in the democracy movement known for consistently advocating moderate tactics have been arrested; and Beijing has announced it will impose a sweeping new anti-sedition law on Hong Kong.

Resistance continues. Activists face greater risks than ever, however, as mass arrests and police brutality have become routine. In line with arguments in Vigil, the Hong Kong democracy movement increasingly resembles the against-long-odds efforts to combat autocratic rule waged in Poland after martial law was imposed there late in 1981 or the protracted anti-colonial struggle against powerful, recalcitrant empires that have been carried out in many parts of the world.

***

Water by Jeffrey Wasserstrom

Hong Kong has long been a place with varied and deep associations with water. “Harbor” is the second term in its two-character name, coming after a word most often translated as “fragrant”. Fish and seafood figure centrally in the storied local cuisine. Hong Kong first gained economic importance due to its role as a hub of trade involving vessels that moved goods across rivers and seas. Humid air, mist, and the torrents of water that lash the city during typhoons are key parts of the local climate. Umbrellas served as protest symbols in 2014. While the city teetered on the brink in 2019, activists striving to create a new alternative world in the streets and in malls and in airport arrival and departure halls in the midst of scenes of destruction, urged one another to “be water,” to adapt their tactics continually to changing circumstances. To resemble “water” means to be flexible in one’s actions, going one place but quickly heading to another if there is too much resistance. The idea can be traced back to longstanding Chinese philosophical traditions, especially Daoism (though metaphors linked to water are important in Confucian texts as well). It has a more specific referent, though, to perhaps the most famous Hong Konger, martial artist and movie star Bruce Lee. “Don’t get set into one form, adapt it and build your own, and let it grow. Be like water,” he said. “Now water can flow, or it can crash! Be water, my friend.”

There’s also the metaphor of the hundred-year flood, the (inaccurate) myth that rivers overflow their banks once a century. Just as the 2019 protest movement was underway in Hong Kong, the author Adam Hochschild published a powerful essay about the parallels of American politics in the years 1919 and 2019. Hochschild conjured up the image of a very particular sort of hundred-year flood: the unleashing of ugly nativist rhetoric in America during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, and now again during that of Donald Trump. Focusing as I have on the events treated in the preceding chapters on my mind, his essay set me wondering whether there were parallels and imperfect analogies linked to events of a century ago worth considering when trying to make sense of the current Hong Kong crisis. There are, I think—providing that we place the past of Shanghai, once the most cosmopolitan city on the China coast, beside Hong Kong’s present.

What exactly happened in that great port of the Yangzi Delta one hundred years ago? There was a dramatic series of protests in which young people took leading roles. There was a general strike. On the whole, the protesters behaved in peaceful ways, but there were some ugly incidents, during which they roughed up people they viewed as outsiders. One goal of the movement was to stop a widely disliked document from going into effect. The protesters directed much of their ire at government officials they viewed as immoral and too ready to do the bidding of men in a distant capital. They also called for the release of protesters who had been arrested and complained about police using too much force in dealing with demonstrators. The movement became in large part a fight for the right to speak out. The protests in the city were preceded by, built on, and expanded a repertoire of action developed during a series of earlier struggles, as some participants in the 1919 demonstrations had been part of shorter waves of activism in 1915 and 1918 and in some cases even in 1905. New tactics were added to the mix in 1919. So were new symbols: for example, a distinctive type of headwear became associated with the protests, as students eschewed wearing straw hats made in Japan for locally made cotton ones.

This analogy is far from perfect. The Shanghai protests of 1919 were part of a nationwide struggle, known as the May Fourth Movement, in honor of the day of the year’s first major demonstration, which took place in Beijing. The current crisis, by contrast, began and has stayed centered in Hong Kong, as did the 2014 Umbrella Movement before it. There have been many more arrests this year, and there were no paving stones thrown or fires set by activists in Shanghai a century ago. The document the protesters of 1919 disliked was not a local bill but an international accord: The Treaty of Versailles, the post–World War I agreement that they objected to because it passed control of former German possessions in Shandong Province to Japan rather than returning them to Chinese control. While one student died from the injuries he received at the hands of the police during the initial protest on May 4, 1919, many fewer demonstrators and bystanders were injured in any part of China one hundred years ago than have been injured in Hong Kong during 2019.

The protesters of 1919 even succeeded in gaining more concessions from the warlords in control of Beijing than those of 2019 have managed to secure. In the immediate wake of the Shanghai General Strike, which stands out as one of the most important of all May Fourth Movement collective actions, three officials that the students claimed were too cozy with Tokyo were removed from their positions and the protesters arrested in Beijing were released. The Chinese delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, who had a role in the proceedings as both China and Japan had come into World War I on the side of the Allies, refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles. These successes by the protesters help to explain why the May Fourth Movement has long been hailed in China as a triumphant struggle. By contrast, while Carrie Lam withdrew the extradition law in September, there have been no moves toward concession regarding the other key demands of the protesters. The authorities have not released those who have been arrested, appointed an independent commission to investigate allegations of police violence, nor retracted their description of early protests as “riots.” Lam has not resigned. There is no universal suffrage in Hong Kong.

But while the May Fourth Movement has a hallowed place in Chinese history now, it was for decades considered largely a failure. While the Chinese delegation to Paris refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles, the accord went into effect anyway. Former German territories in Shandong fell under Japanese control. The May Fourth activists were no more successful at preventing territory they cared about from going from the control of one colonial power to another. And the Japanese seizure of Shandong, which was preceded by its seizing of Korea and Taiwan, was followed in 1931 by Tokyo taking Manchuria and later moving further into China and other neighboring lands.

Japan asserted in many cases that it was not taking over territories, but freeing them from colonial rule, and allowing them to be governed at last by locals. They made this claim about Shanghai, proclaiming in the early 1940s that it was finally liberated from all forms of foreign control, even as Japanese troops and Chinese puppet officials control the city. They made this claim about Manchuria as they put Pu Yi, the ethnically Manchu former Last Emperor of the Qing Dynasty, on the throne, as a ruler beholden to Tokyo. They did not talk of a single empire with multiple systems, but rather of a Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. Beijing, too, does not talk of having an empire, but its handling of Tibet and Xinjiang rhymes with Tokyo’s imperial approach. Beijing’s dreams for Hong Kong, which are nightmares to those on the streets, rhyme with Tokyo’s proclamations about Shanghai. The terms are new— “One Country, Two Systems,” “Greater Bay Area”—but when it comes to fantasies and raw power, there are disturbing echoes.

History does not repeat itself. In 1919, the Western powers actively aided Japan’s move into Shandong. Viewed within a hundred-year framework, the limited international concern about Hong Kong’s fate is deeply worrying. So, too, are the signals some world leaders, including Vladimir Putin and Donald J. Trump, have been sending to Xi Jinping during the current crisis, which convey a sense that whatever he does will be just fine with them, as long as it does not impinge on their plans for their own nations. Hundred-year floods can wreak many different kinds of damage.

Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink was published in February 2020. To read more about the book click here[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Jan 20 | Campaigns -- Featured, Free Speech and the Law, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1579268532812{margin-bottom: 30px !important;background-color: #f5f5f5 !important;}”]Please note: This is part of a series of guides produced by Index on Censorship on the laws related to freedom of expression in England and Wales. They are intended to help understand the protections that exist for free speech and where the law currently permits restrictions.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]This guide is available to download as a PDF here.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”112028″ img_size=”large” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_raw_html]JTNDZGl2JTIwc3R5bGUlM0QlMjJmb250LXNpemUlM0EuOWVtJTNCcGFkZGluZyUzQTVweCUzQmJhY2tncm91bmQtY29sb3IlM0FXaGl0ZVNtb2tlJTNCZmxvYXQlM0FyaWdodCUzQm1hcmdpbi1sZWZ0JTNBMTVweCUzQndpZHRoJTNBNDAlMjUlM0IlMjIlM0UlM0NoNCUzRVRhYmxlJTIwb2YlMjBjb250ZW50cyUzQyUyRmg0JTNFJTBBJTNDb2wlM0UlMEElM0NsaSUzRSUzQ2ElMjBocmVmJTNEJTIyJTIzdG9wJTIyJTNFQ2hpbGQlMjBwcm90ZWN0aW9uJTIwb2ZmZW5jZXMlMjBleHBsYWluZWQlM0MlMkZhJTNFJTNDJTJGbGklM0UlMEElM0NsaSUzRSUzQ2ElMjBocmVmJTNEJTIyJTIzY3AyJTIyJTNFT3ZlcnZpZXclMjBvZiUyMFVLJTIwbGF3cyUzQyUyRmElM0UlM0MlMkZsaSUzRSUwQSUzQ2xpJTNFJTNDYSUyMGhyZWYlM0QlMjIlMjNjcDMlMjIlM0VQcm90ZWN0aW9uJTIwb2YlMjBDaGlsZHJlbiUyMEFjdCUyMDE5NzglMjAlRTIlODAlOTMlMjBUYWtpbmclMkMlMjBtYWtpbmclMkMlMjBzaG93aW5nJTIwYW5kJTIwZGlzdHJpYnV0aW5nJTIwaW5kZWNlbnQlMjBwaG90b2dyYXBocyUyMG9mJTIwY2hpbGRyZW4lM0MlMkZhJTNFJTNDJTJGbGklM0UlMEElM0NsaSUzRSUzQ2ElMjBocmVmJTNEJTIyJTIzY3A0JTIyJTNFQ29yb25lcnMlMjBhbmQlMjBKdXN0aWNlJTIwQWN0JTIwMjAwOSUyMCVFMiU4MCU5MyUyMFBvc3Nlc3Npb24lMjBvZiUyMHByb2hpYml0ZWQlMjBub24tcGhvdG9ncmFwaGljJTIwaW1hZ2VzJTIwb2YlMjBjaGlsZHJlbiUzQyUyRmElM0UlM0MlMkZsaSUzRSUwQSUzQ2xpJTNFJTNDYSUyMGhyZWYlM0QlMjIlMjNjcDUlMjIlM0VDcmltaW5hbCUyMEp1c3RpY2UlMjBBY3QlMjAxOTg4JTIwJUUyJTgwJTkzJTIwUG9zc2Vzc2lvbiUyMG9mJTIwYW4lMjBpbmRlY2VudCUyMHBob3RvZ3JhcGglMjBvZiUyMGElMjBjaGlsZCUzQyUyRmElM0UlM0MlMkZsaSUzRSUwQSUzQ2xpJTNFJTNDYSUyMGhyZWYlM0QlMjIlMjNjcDYlMjIlM0VEZWZlbmNlcyUyMHRvJTIwY2hpbGQtcHJvdGVjdGlvbiUyMGNyaW1lcyUzQyUyRmElM0UlM0MlMkZsaSUzRSUwQSUzQ2xpJTNFJTNDYSUyMGhyZWYlM0QlMjIlMjNjcDclMjIlM0VUaGUlMjBMYW56YXJvdGUlMjBDb252ZW50aW9uJTNDJTJGYSUzRSUzQyUyRmxpJTNFJTBBJTNDbGklM0UlM0NhJTIwaHJlZiUzRCUyMiUyM2NwOCUyMiUzRU9ubGluZSUyMEhhcm1zJTIwV2hpdGUlMjBQYXBlciUzQyUyRmElM0UlM0MlMkZsaSUzRSUwQSUzQ2xpJTNFJTNDYSUyMGhyZWYlM0QlMjIlMjNjcDklMjIlM0VUaGUlMjBwb3dlcnMlMjBvZiUyMHRoZSUyMHBvbGljZSUyMGFuZCUyMHByb3NlY3V0aW5nJTIwYXV0aG9yaXRpZXMlM0MlMkZhJTNFJTNDJTJGbGklM0UlMEElM0MlMkZvbCUzRSUzQyUyRmRpdiUzRQ==[/vc_raw_html][vc_custom_heading text=”1. Child protection offences explained” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” el_id=”ct1″][vc_column_text]Child protection is a sensitive area of law and a deserved focus of public concern.

As there is no clear legal definition of the concept of indecency, and because of the sensitivity of the matter, decisions made by the police and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) can be subjective and inconsistent, and in the wrong context can seriously compromise freedom of expression rights. For that reason, it is important to be aware of the legal framework and, if you are concerned that your artistic work, journalistic work or other projects or behaviour will be scrutinised under child protection laws, to take practical preparatory steps at an early stage.

The offences set out in law cover a broad spectrum of behaviour. If someone makes, displays or possesses images of children that could be considered to be indecent, obscene or pornographic, it could be a serious criminal offence. The circumstances or motivation of a defendant are not relevant to determining whether or not the image is indecent. It is for a jury to decide whether or not images are indecent, by asking whether the images offend based on recognised standards of propriety. Information about an investigation, an arrest and a prosecution can be kept and may be legally disclosed to others by police in certain circumstances. Convicted people may be treated as sex offenders depending on the seriousness of the charges.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″ el_id=”cp2″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”2. Overview of UK laws” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]The UK laws that can be used to prosecute people in relation to images of children include:

- Protection of Children Act 1978, which prohibits making, taking, permitting to be taken, distributing or showing indecent photographs (including film or computer data such as scans) or “pseudo-photographs” of children. As defined by the act, “children” are people under 18.

- Criminal Justice Act 1988, which creates an offence of possessing an indecent photograph or “pseudo-photograph” of a child.

- Coroners and Justice Act 2009, which criminalises the possession of non-photographic images of children (including cartoons, paintings and drawings) which are pornographic and grossly offensive, disgusting or otherwise of an obscene character.

- Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 1955, which criminalises the printing, publishing, hiring or selling of a book, magazine or similar work, which consists mostly of stories told in pictures and is of a kind likely to fall into the hands of children or young people, and which portrays acts of violence or cruelty, the commission of crimes or repulsive incidents in such a way that it might “tend to corrupt” a child reader. There have been very few prosecutions for this offence.

- Indecent Displays (Control) Act 1981, which criminalises the public display of “indecent matter”.

- Obscene Publications Act 1959, which criminalises the publication of an “obscene article”.

- Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, which gives police a range of statutory powers to stop, search, and arrest individuals.

- Serious Crime Act 2015, which created the offence of being “in possession of any item that contains advice or guidance about abusing children sexually”. The crime is called “possession of paedophile manual”. If a defendant has material containing advice or guidance about how to make indecent photographs (but not pseudo-photographs) of children they will likely be committing an offence under this act.

These laws are intended to protect the rights of children. The police and prosecuting authorities should also consider the free-expression rights of alleged perpetrators under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) when making decisions about whether to investigate or prosecute.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″ el_id=”cp3″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”3. Protection of Children Act 1978 – Taking, making, showing and distributing indecent photographs of children” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Individuals may commit a criminal offence under the Protection of Children Act 1978 in relation to indecent photographic, film and “pseudo-photographic” images (which are defined as non-photographic images that appear to be photographs – these could be computer-generated). Under the legislation, “photograph” includes negatives, tracings of photographs and data stored on a computer or electronically that is capable of being converted into photographs. For a photograph or film to be considered indecent under the law, it must be found by the jury or court to offend recognised standards of propriety. This is an extremely fluid test that changes along with society’s changing expectations.

The criminal offence set out in Section 1 of the 1978 act prohibits the making, taking, permitting to be taken, distributing, or possessing (with a view to distributing) indecent photographs or pseudo-photographs of children. “Making” an indecent image is defined as “to cause [it] to exist, to produce by action, to bring about” (R v Bowden 2000). It includes intentionally opening an email attachment knowing that it contains (or is likely to contain) an indecent photograph of a child.

Equally, accessing a pornographic website and knowing that indecent images of children will automatically be generated as on-screen “pop-ups” amounts to “making” an indecent image of a child (as will knowing the image will be automatically saved to a hard drive, and keeping it there). Downloading an image from a website on to a computer screen and “live-streaming” indecent images also constitute “making” an indecent image (R v Smith and R v Jayson 2002). The making must “be a deliberate and intentional act with knowledge that the image made was, or was likely to be, an indecent photograph of a child (R v Smith and R v Jayson 2002). An unintended copying or storing of an image does not constitute the offence of “making” an indecent image. Consequently, someone who opens a doubtful email attachment that turns out to be an indecent photograph or whose computer automatically saves it in its cache is not guilty of making those photographs (Atkins v DPP and Goodland v DPP 2000).

“Sexting” (the creating, sharing, sending or posting of sexually explicit messages or images via mobile phones or other electronic devices), if it involves someone under the age of 18, may amount to distributing or showing an indecent photograph of a child under Section 1(b) of the Protection of Children Act.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″ el_id=”cp4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”4. Coroners and Justice Act 2009 – Possession of prohibited non-photographic images of children” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]It is a crime under the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 to possess non-photographic images that are grossly offensive, disgusting or otherwise of an obscene character. Non-photographic images include computer-generated images (CGIs), cartoons, manga images, and drawings. They can be still or moving, and produced by any means. The images must also be pornographic, meaning it can be assumed they were principally or solely produced for the purpose of sexual arousal. The image must also focus solely or principally on the anal or genital region of a child, or show certain specific sexual acts (such as oral sex with, or in the presence of, a child). There is an exclusion from the offence for works classified by the British Board of Film Classification.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

The difference between Protection of Children Act 1978 and Coroners and Justice Act 2009 crimes

Photos and films (and images appearing to be photos)

Protection of Children Act 1978

A photograph of a naked child in a room full of clothed people could be considered indecent under the Protection of Children Act if it offends what the jury considers the “recognised standards of propriety”. This will depend on the context and all the circumstances surrounding the image’s creation.

Drawings, paintings and sculptures

Coroners and Justice Act 2009

Under the Coroners and Justice Act there is a higher test for a drawing, painting or sculpture. It needs to be grossly offensive, disgusting, or obscene and pornographic and it needs to depict certain sexual acts featuring children or certain sexual parts of a child’s body. For example, a drawing of a 14-year-old masturbating could be prohibited because it may be considered pornographic (meaning it can be reasonably assumed to have been produced for the purpose of sexual arousal), and obscene, and it involves the sexual act of a child.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1579691218533{margin-top: 15px !important;margin-bottom: 15px !important;padding-top: 5px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #21277a !important;}”]

Case study: Obscene manga?

In October 2014, Robul Hoque admitted 10 counts of possessing prohibited images of children at Teesside Crown Court. Police seized Hoque’s computer from his home in June 2012 and found 288 still and 99 moving images. The images were in Japanese manga or anime-style and were not of real people. However, they were classified as prohibited images because they depicted young girls, some in school uniforms and some engaging in sexual activity.

Hoque had been convicted some six years prior of making “indecent pseudo-photographs” for having realistic-seeming “Tomb Raider-style” computer-generated pictures of fictional children.

The conviction was criticised in online media. Spiked magazine pointed out that the material Hoque was looking at did not involve any actual children (only drawings) and he had no convictions for child abuse or possession of actual child pornography, and that he was not a threat to children. His consumption of manga magazines could therefore not be said to result in any exploitation of children or create a market for that exploitation (which are the usual arguments for criminalising possession of indecent images of children). In the writer’s words: “The fact that possessing something in private, which gives a window into your thoughts and nothing else, can now be a crime, shows how insidious and deranged the moral panic over paedophilia has become.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″ el_id=”cp5″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”5. Criminal Justice Act 1988 – Possession of an indecent photograph of a child” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Under the Criminal Justice Act 1988, it is a crime to simply possess an indecent photograph (or pseudo-photograph) of a child. People “possess” a photograph if they are capable of accessing or retrieving it and they are aware that they possess an image or images. Photos are not retrievable if they are located on a hard drive that requires specialist software to access, which the suspect does not have. To possess the photo, the suspect does not need to have opened or scrutinised it. A person receiving unsolicited indecent images on WhatsApp, which automatically download to the phone’s memory, will likely be found to possess indecent photographs. However, if the suspect has not seen the photos, and has no reason to believe they are indecent, then he or she will have a defence under Section 160(2)(b).[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1579690479213{margin-top: 15px !important;margin-bottom: 15px !important;padding-top: 5px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #21277a !important;}”]

Case study: Possession of digital files

The case of R v Cyprian Okoro 2018 concerned London doctor Cyprian Okoro, who received an unsolicited indecent images of children on WhatsApp. It was downloaded on to his phone and found in a vault application, which is a storage area protected by a password. It was impossible to tell whether the video had been viewed.

Okoro said that when he received the message on WhatsApp he did not view it and intended to delete it, but it went into the vault by mistake. He did not realise it was indecent until he viewed it later with his lawyer and the police. The trial judge initially told the jury that Okoro had admitted that he “possessed” the indecent images, and the only question was whether or not he had a defence.

Okoro’s defence lawyer then raised the question of whether “possessing” an indecent photo required the defendant to know he possessed the images and that the images were indecent. The court said that possession required only that the suspect was aware they had the image, and they had the capacity to access and retrieve it. The suspect did not have to know that the image was indecent.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″ el_id=”cp6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”6. Defences to child-protection crimes” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]If the CPS decides to prosecute, there are limited defences available. In the case of distributing or showing indecent photographs of children prohibited under the Protection of Children Act 1978, and possessing indecent photographs under the Criminal Justice Act 1988, alleged perpetrators have to demonstrate that:

- they had not seen the images and had no reason to suspect they were prohibited;

- or they had a “legitimate reason” for being in possession of them or showing or distributing them.

If the child in the photograph is over 16 and is the spouse or civil partner of the perpetrator, no offence under Section 1 of the Protection of Children Act has been committed. This includes making or taking an indecent photograph. The same is true for the offence of possessing indecent photographs under the Criminal Justice Act.

There is also an additional defence under the Criminal Justice Act that the photo was sent to the defendant without any prior request made by him or her, or on his or her behalf, and that the defendant did not keep it for an unreasonable time. There is very little information available on what amounts to an “unreasonable time”. CPS guidance states that this is a question that will be determined by juries on a case-by-case basis.

The leading case on the concept of “legitimate reason” (Atkins v Director of Public Prosecutions 2000) suggests that the defence applies only in very restricted circumstances, such as when it is necessary to possess the images to conduct forensic tests or for legitimate research. It also suggests that any court should approach such a defence with scepticism. The court in Atkins said that:

“The central question where the defence is legitimate research will be whether the defendant is essentially a person of unhealthy interests in possession of indecent photographs, or by contrast a genuine researcher with no alternative but to have this sort of unpleasant material in his possession. In other cases there will be other categories of legitimate reasons advanced. They will each have to be considered on their own facts.”

As stated above, to a certain extent those who could be considered to have a “legitimate reason” – such as artists and galleries – can rely on their right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the ECHR: the right to receive and impart opinions, information and ideas, including those which shock disturb and offend. That right is qualified by the need to protect the rights and freedoms of others (in this context, children), and a 2001 case (R v Smethurst 2002) found that the Protection of Children Act 1978 offence was compatible with Article 10 rights to free expression under the ECHR.

In the context of child protection, the rights of children not to be exploited and those of a young audience will be set against the right to freedom of expression. That means the police and courts are permitted in some circumstances to act in ways that will compromise the freedom of expression rights of individuals. Any decision they make will require these competing objectives to be balanced.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″ el_id=”cp7″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”7. The Lanzarote Convention” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]In 2018, the UK ratified the Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse, also known as the “Lanzarote Convention”. It requires the UK to criminalise many offences concerning child pornography, including “knowingly obtaining access, through information and communication technologies, to child pornography”. This may well be covered through the Protection of Children Act 1978 offence of making an indecent image of a child (which can cover downloading such images, or knowingly entering websites where such pop-up images will appear) or the crime of possessing an indecent image under the Criminal Justice Act 1988. Alternatively, the UK may be obliged to create a more specific criminal offence.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″ el_id=”cp8″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”8. Online Harms White Paper” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]The government’s 2019 Online Harms White Paper proposed establishing a statutory duty of care to make companies operating on the internet more responsible for their users’ safety and to “tackle harm caused by content or activity on their services.” An independent regulator would be set up to enforce compliance. The white paper stated that enforcement in respect of activity involving harm to children would be prioritised.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″ el_id=”cp9″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”9. The powers of the police and prosecuting authorities” font_container=”tag:h1|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Under Section 4 of the Protection of Children Act 1978, a judge may issue a warrant authorising police to enter and search any premises where they reasonably believe an indecent photograph (or pseudo-photograph) of a child will be found. The warrant can permit the police to seize any articles they reasonably believe are – or include – indecent photographs of children.

Section 67 of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 applies these powers to the “possession of prohibited images of children” offence. So if police reasonably believe they will find prohibited images of children other than photographs (such as computer-generated images, cartoons, manga images and drawings), they can request a warrant from a judge to search the place and seize any prohibited material.

If the police seize indecent photographs or prohibited images during a search, they may apply to court to “forfeit” them (that is, destroy or condemn them), or they may automatically do so if no one claims the property after the police inform all possible owners of the property of their intention to forfeit the property.

The Indecent Displays (Control) Act 1981 empowers magistrates to issue a warrant to a police officer who has reasonable grounds for suspecting someone is displaying indecent matter to enter premises and seize any articles used in the commission of the indecent-matter crime. The act also empowers a police officer to “seize any article which he has reasonable grounds for believing to be or to contain indecent matter and to have been used in the commission” of the indecent-matter offence.

Prosecutions under the Protection of Children Act 1978, the Criminal Justice Act 1988 and the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 require the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions. As with all criminal cases, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) will consider whether it is in the “public interest” to prosecute, taking into consideration the competing rights of the alleged perpetrator and others, including children. A reading of the CPS code, which governs its decisions and its list of public-interest factors, suggests that there will be a lower threshold for prosecutions involving offences against children.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1579690942191{margin-top: 15px !important;margin-bottom: 15px !important;padding-top: 5px !important;padding-right: 10px !important;padding-bottom: 10px !important;padding-left: 10px !important;background-color: #21277a !important;}”]

Convention on the Rights of the Child

The Convention on the Rights of the Child is an international treaty established in 1989 and signed by 196 countries. It sets out the civil, political, educational, health and other rights of children which countries signing up to the treaty agree to respect. For example, with regard to free expression, the treaty says: “States parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.” It also lists a separate free-expression right for children in Article 13. Under Article 34, the signatories agree to “protect the child from all forms of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse”, including the “exploitative use of children in pornographic performances and materials.” The UK ratified the treaty in 1991. The USA has signed but not ratified it, meaning it intends to comply with the treaty but is not bound by it.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator el_width=”80″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Ackowledgements” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]This guide was produced by Index on Censorship, in partnership with Clifford Chance.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 May 19 | Artistic Freedom Case Studies

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Name of Art Work: Exhibit B

Artist/s: Brett Bailey

Date: September 2014

Venue: The Vaults, presented by The Barbican Centre

Brief description of the artwork/project: The Barbican’s publicity material described Exhibit B as: “a human installation that charts the colonial histories of various European countries during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when scientists formulated pseudo-scientific racial theories that continue to warp perceptions with horrific consequences.”[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”94431″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Why was it challenged? ” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]A campaign is formed in response to Exhibit B: Boycott the Human Zoo is a coalition of anti-racism activists, trade unions, artists, arts organisations and community groups. They set up an online petition which is signed by over 22,000 people, calling on the Barbican to decommission the work and withdraw it from their programme. The key objections named in the petition are:

- “[It] is deeply offensive to recreate ‘the Maafa – great suffering’ of African People’s ancestors for a social experiment/process.

- Offers no tangible positive social outcome to challenge racism and oppression.

- Reinforces the negative imagery of African Peoples

- Is not a piece for African Peoples, it is about African Peoples, however it was created with no consultation with African Peoples”

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”What action was taken?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]The Barbican issues a response to the petition, acknowledging that Exhibit B “has raised significant issues” but commenting that this is not a reason to cancel the performance. They accept the campaigners right to peaceful protest but ask that they “fully respect our performers’ right to perform and our audiences’ right to attend.” Campaigners are in communication with senior management at the Barbican, and they contact the police about their plan to picket the venue. Kieron Vanstone, the director of the Vaults also contacts the British Transport Police – as they have jurisdiction over the Vaults – about the possibility of needing additional policing on the night. nitroBEAT, who had cast the show in London and took a leading role in mediating between the two ‘sides’ organises a debate at Theatre Royal Stratford East the night before the opening.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”What happened next?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]On the opening night of the installation, just one of the two BTP PCs allocated to the picket attends. Protesters breach the barriers and block the doors to the venue. The PC on duty calls for backup officers. ACC Thomas reports “that ‘about’ 12 BTP officers and 50 Metropolitan Police Service Officers respond to these calls.” Vanstone describes a huge police presence, including riot police, dogs and helicopters overhead. When Inspector Nick Brandon, the BTP senior officer in charge asks what the campaign organisers want, they respond that they want the show to be closed down, or they will picket it every evening. Sara Myers of Boycott the Human Zoo reports that Brandon says “‘we need to be out fighting crime. This is much ado about nothing, and we haven’t got the resources to police it.” The Inspector recommends that Vanstone closes the show. In partnership with the Barbican, Vanstone agrees to do so. When the campaigners request written confirmation, the police officer ensures that the venue provides this. The installation is cancelled.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Reflections” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Louise Jeffreys – Artistic Director, Barbican

The Barbican’s experience of Exhibit B was a catalyst for a significant amount of change within the organisation. The protests and eventual cancellations of performances led to us thinking deeply about a number of areas of our work, looking at how we could learn from this situation so we could continue to present challenging work and ensuring the experience we had didn’t contribute to an environment where organisations felt they couldn’t programme artists whose work deals with difficult subjects.

Our starting point was the belief that it was important that we remained an organisation willing to take risks and that we didn’t want to shy away from putting on work that invites discussion and debate. To do this we felt we needed to have the planning processes in place to ensure this kind of work could be presented safely, that we were confident about how it fitted into our wider programme, that we contextualise it in the right way and that we have clear, artistic reasons for programming it.

This work has included formalising our risk review process for our artistic programme; it involved us contributing to the development of What Next’s practical guidance for arts organisations on meeting ethical and reputational challenges; and it continued with the development of the Barbican’s first ethics policy, which we now use as a basis for making ethical decisions across areas such as programming, fundraising and partnerships.

Combined, these measures have all contributed to us becoming more confident in the work we present, encouraging a collaborative, organisation-wide approach to making difficult decisions, dealing with risk and investing in artists and works that deal with potentially controversial issues.

The Exhibit B experience also led to us further interrogating our approach to equality and inclusion. This led to positive changes such as the development of a new Equality and Inclusion strategy and the building of relationships with artists and companies who have added to the creative richness and relevance of our programme as we look to try and represent the widest possible range of human experiences on our stages, in our galleries and on our screens.

The cancellation also led us to think about how we work with the police, and the importance of their role in protecting free expression. At the time of the Exhibit B protests we felt we had no choice but to follow their advice when they recommended we cancel all future performances. I feel we’d question this kind of decision-making more now, with the work we’ve done since the closure making us much better informed on the legal framework around freedom of expression.

Sara Myers – Boycott The Human Zoo Campaign lead

At the time the black community was campaigning against so many things – deaths in police custody, acts of racism – and there never seemed to be any victory. I think the legacy of Exhibit B is that it gave a monumental landmark victory which we hadn’t had. In the last 30 years, this was the one thing that we won, the one time that our voices were heard and taken seriously. I know a lot of people were talking about censorship and not having an understanding of art, and I think all of that is irrelevant. It was about not taking that narrative of our history, that slave narrative and keeping us boxed in there; we are more than that, and you will listen to us.

There were two camps, one called me a reincarnation of Stalin and the other thought I was going to be the new speaker for all things black. But what people failed to realise was [while] I was the face of the campaign, I started the petition and led the campaign it was owned by the whole black community – pan-African, Christian, Muslim, LGBT, young, old, celebrities.

A lot more people began to speak out. In fact it went a bit crazy after Exhibt B, there were petitions about everything and everybody was calling everybody out and we got a lot of things taken down. It birthed a lot of new activists and Exhibit B became a movement. The way [we used] social media, institutions don’t want that, they don’t want to be tagged and dragged for days on social media. Brett was challenged in Paris [where] people were tear-gassed and water-cannoned which was terrible. It went to Ireland, very much on the quiet, but there was not a very large black of mixed race community [where it went]. He tried to take it to Brazil and that got shut down. He tried to take it to Toronto, but it was [challenged} and it didn’t go there.]

Another legacy was that academics were talking about the whole campaign, whether positively or negatively. It was a very controversial campaign and it opened up conversation about so many things – about racism, institutional racism, how an emerging black artist might not get a platform, but a potentially racist guy from South Africa might. Who is censoring what? Who is at the helm of censorship? What about all the exhibitions that they haven’t put on? Is it us campaigning, peacefully protesting. Who owns the story? Also how the media reported it as a violent, angry mob, and yet there wasn’t one arrest. How the Barbican didn’t take responsibility for the whole part they played in this.

For me personally – my claim to fame will be Exhibit B and that’s monumental. To know that I’m part of Black British History. Maybe in Black History Month, they’ll have my picture and talk about what I did. And that’s great because I’ve got grandchildren and they’ll be able to see that.

I’m not saying that Brett isn’t a talented artist. It was the imagery was traumatic for a community because it was not part of [our] ancient history. This is something we live every day, down to deportations – in fact that there was one today people who have lived here all their lives deported back to Jamaica. We are still living the ramifications of that, whereas Brett is quite removed from his colonial past. It also brought up a massive discussion about colonialism and the effects of colonialism today.

A detailed case study of the policing of the picket of Exhibit B is available here.

Stella Odunlami – actor, director, performer in Exhibit B (London, Ireland, South Korea and Estonia)

The piece arrived at a time of change. Those tensions around the idea of race and representation had always been there, but the squeeze of the government cuts to a lot of provision, particularly to black and minority backgrounds, were being felt. The rhetoric around our wonderful multi-cultural society was starting to fall away. It landed on a sore spot, places were pus had been building up under the surface. All these conversations and interactions around the legacy and inherited histories that we are being forced to deal with at the moment – [it] brought all of that to the surface.

It has made me hyper aware of the lack of space and opportunity to have these conversations and how desperately we need them. We don’t speak of what the West did in Africa as a form of genocide. Within the black community, whatever that may mean, people find it really hard to engage with conversations around race in public forums because the conversation always feels dishonest, because the ground zero hasn’t been reached. So when people talk about who makes art, access to art, access to funding and education we are never going back to the beginning to understand why that is.

I still think it’s a beautiful, powerful piece. It opened up conversations; everybody who sees it is automatically implicated in some way or another. You have to begin to confront your own relation to history, and that is something that we don’t do very often. I’m still trying to unpack my ideas around the existing theatre model and what theatres as cultural spaces are aiming to do. Very often the places that present this work are only interested in an economic model and don’t recognise or feel the wider responsibility. It comes down to what are we demanding of our arts and cultural spaces, what we want from them.

Having taken the show to Ireland, to South Korea and Estonia, it surprised me how my concept of the show being linked explicitly to the European history of colonisation, was being refracted through different prisms. At around the time we were in Ireland, the story broke about many women in the early 1900s who had fallen pregnant to black men, had been held, and had their children taken away. Mass burial sites uncovered these children who had been treated appallingly and had passed. This history had been repressed by the state and the church, echoes of that were only starting to be discussed. I was nervous before going to [Tallinn] because I had heard about incidents of violence against black African bodies there. There were a lot of students coming from Africa because there seem to be more scholarships and migration for education seems to be easier. They are having to think about migration, without following the western European model which hasn’t really worked. South Korea’s history with Japan brought those conversations to the fore. They had no idea about what had happened in these parts of the world and people came back with notepads, to take down the names, the places, the dates.

The last performance was in Tallinn, it was very hard, really sad. We all felt such a responsibility for these stories, for them being shared and acknowledged. Whose stories are remembered, whose stories are told. The weight of that responsibility, and the personal investment we all had in that, is huge.[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”Case Studies” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”15471″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

03 May 19 | Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103553″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]The investigation into the July 2016 murder of Belarusian journalist Pavel Sheremet in Kyiv, Ukraine continues to be shrouded in mystery. Ukrainian authorities have remained silent, releasing no new information since July 2017.

“The authorities in Ukraine must ensure that there is a fully transparent investigation and they must do their utmost to make real progress,” Joy Hyvarinen, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship said. “There are now too many unanswered questions related to the murder of Pavel Sheremet. The murder cannot be allowed to go unpunished.”

Journalists from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, in partnership with Slistvo.info studied a number of leads on the case and analysed footage from more than 50 different surveillance cameras. They used their findings to create an investigative documentary called “Killing Pavel” which later won the IRE Medal, the highest honour that can be received for investigative journalism. One of the most significant findings detailed in the documentary, which was released in May 2017, was the revelation that a former Ukrainian secret service agent and two unidentified individuals were present outside Sheremet’s apartment when the explosives were planted under his car.

Petro Poroshenko, the former president of Ukraine, said in July 2016 that justice for Sheremet’s murder was a “matter of honour” and that the case would be treated with utmost priority. However, he has failed to follow through on this bold statement. Ambassadors from the USA, Canada, the UK, France, Germany, Italy and Japan have emphasised “the importance of continuing the investigation” in order to bring those responsible to justice. Pressures from other countries, human rights organisations and journalists rights groups, have had little effect on the overall progress of the investigation.

Sheremet, who primarily covered political figures, received considerable recognition for his work exposing corruption in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. According to a letter from Olena Prytula, his partner and the owner of the Ukrainska Pravda news site, to the prosecutor general Yury Lutsenko, Sheremet “was stripped of his Belarusian citizenship due to his criticism of the Belarusian government”. In addition to spending three months in prison for speaking out against the government of Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, Sheremet’s Belarusian cameraman, Dzmitry Zavandski was also kidnapped and killed in 2000 after returning to Belarus from a reporting trip in Russia.

The presidents of Ukraine and Belarus met on 20 June 2017 to solely discuss “economic co-operation” between the two countries. However, this meeting was highly criticised by journalists for being held on the first anniversary of Sheremet’s murder and the honours with which Lukashenko was received by Poroshenko.

Poroshenko’s support of Lukashenko and his desire to establish closer relations with Belarus conflicted with the promises he made to attack corruption, and bring resolve to Sheremet’s case. Mustafa Nayyem, a Ukrainian journalist and the co-founder of the Hromadske Network, criticised Poroshenko for praising Lukashenko, whose acts of corruption and crimes against human rights directly tie him to Sheremet’s case. In a Facebook post that later received substantial support from the public, Nayyem wrote that Lukashenko “destroyed freedom of speech in his country, under whom hundreds of journalists have disappeared or been jailed” and emphasised the fact that it was “the very same Lukashenko under whom Pavel was sent to pretrial detention and his friend and cameraman was brutally murdered”.

Volodymyr Zelenskiy, a Ukrainian comedian who defeated Poroshenko in the Ukraine presidential election on 21 April 2019 by a landslide winning 73% of vote, has repeatedly denounced corruption and has promised to expel it from the Ukrainian government; however he has not yet addressed the future development of Sheremet’s case or any other unsolved cases. Although Sheremet’s case has been ignored for almost three years, it has not been forgotten.

On the second anniversary of Sheremet’s murder, Marie Yovanovitch, the US ambassador to Ukraine, said in an interview for Radio Liberty that Sheremet “played an immensely important role here in Ukraine, in terms of finding out what was happening and presenting it to the Ukrainian people so that they could make their own decisions about the situation in the Ukraine”. Furthermore, she emphasised the importance behind the renewal of the investigation, and stated that the “Ukrainian people deserve to know the truth about what happened”. However, the truth continues to be sidestepped regardless of continual demands from country ambassadors, human rights organisations, journalists and the Ukrainian community for justice.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1556881896863-0ee92b86-a4fa-7″ taxonomies=”8568″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Feb 19 | Magazine, News and features, Student Reading Lists

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Salman Rushdie. Credit: Fronteiras do Pensamento

On 14 February 1989 Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to execute author Salman Rushdie over the publication of The Satanic Verses, along with anyone else involved with the novel.

Published in the UK in 1988 by Viking Penguin, the book was met with widespread protest by those who accused Rushdie of blasphemy and unbelief. Death threats and a $6 million bounty on the author’s head saw him take on a 24-hour armed guard under the British government’s protection programme.

The book was soon banned in a number of countries, from Bangladesh to Venezuela, and many died in protests against its publication, including on 24 February when 12 people lost their lives in a riot in Bombay, India. Explosions went off across the UK, including at Liberty’s department store, which had a Penguin bookshop inside, and the Penguin store in York.

Book store chains including Barnes and Noble stopped selling the book, and copies were burned across the UK, first in Bolton where 7,000 Muslims gathered on 2 December 1988, then in Bradford in January 1989. In May 1989 between 15,000 to 20,000 people gathered in Parliament Square in London to burn Rushdie in effigy.

In October 1993, William Nygaard, the novel’s Norwegian publisher, was shot three times outside his home in Oslo and seriously injured.

Rushdie came out of hiding after nine years, but as recently as February 2016, money has been raised to add to the fatwa, reminding the author that for many the Ayatollah’s ruling still stands.

Here, 30 years on, Index on Censorship magazine highlights key articles from its archives from before, during and after the issue of the fatwa, including two from Rushdie himself.

Cuba today, the March 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

World statement by the international committee for the defence of Salman Rushdie and his publishers

March 1989, vol. 18, issue 3

On 14 February the Ayatollah Khomeini called on all Muslims to seek out and execute Salman Rushdie, the author of The Satanic Verses, and all those involved in its publication. We, the undersigned, insofar as we defend the right to freedom of opinion and expression as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, declare that we also are involved in the publication. We are involved whether we approve the contents of the book or not. Nonetheless, we appreciate the distress the book has aroused and deeply regret the loss of life associated with the ensuing conflict.

Read the full article

Islam & human rights, the May 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Pandora’s box forced open

Amir Taheri

May 1989, vol. 18, issue 5

‘What Rushdie has done, as far as Muslim intellectuals are concerned, is to put their backs to the wall and force them to make the choice they have tried to avoid for so long’. Last year, when poor old Mr Manavi filled in his Penguin order form for 10 copies of Salman Rushdie’s third novel, The Satanic Verses, he could not have imagined that the book, described by its publishers as a reflection on the agonies of exile, would provoke one of the most bizarre diplomatic incidents in recent times. Mr Manavi had been selling Penguin books in Tehran for years. He had learned which authors to regard as safe and which ones to avoid at all costs.

Read the full article

Islam & human rights, the May 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Jihad for freedom

Wole Soyinka

May 1989, vol. 18, issue 5

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

Read the full article

South Africa after Apartheid, the April 1990 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Reflections on an invalid fatwah

Amir Taheri

April 1990, vol. 19, issue 4

Broadly speaking, three predictions were made. The first was that Khomeini’s attempt at exporting terror might goad world public opinion into a keener understanding of Iran’s tragedy since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The fact that the Ayatollah had executed thousands of people, including many writers and poets since his seizure of power in Tehran had provoked only mild rebuke from Western governments and public opinion. With the fatwa against Rushdie, we thought the whole world would mobilise against the ayatollah, turning his regime into an international pariah. Nothing of the kind happened, of course, and only one country, Britain, closed its embassy in Tehran – and that because the mullahs decided to sever.diplomatic ties. In the past twelve months Federal Germany and France have increased their trade with the Islamic Republic to the tune of II and 19 per cent respectively. The EEC countries and Japan have, in the meantime, provided the Islamic Republic with loans exceeding £2,000 million. The stream of European and Japanese businessmen and diplomats visiting Tehran turned into a mini-flood after Khomeini’s death last June.

Read the full article

South Africa after Apartheid, the April 1990 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Salman Rushdie and political expediency

Adel Darwish

April 1990, vol. 19, issue 4

When I reviewed Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses in September 1988, it never crossed my mind to make any reference to possible offence to Muslim readers, let alone to anticipate the unprecedented international crisis generated in the months that followed. I do not think I was naive – as an LBC radio reporter suggested when she interviewed me at the first public reading from The Satanic Verses in June 1989. On the contrary, I can claim more than many that I am able to understand what Mr Rushdie was trying to say in his book, and the way the crisis has developed. Like Mr Rushdie, I am a British writer, born to a Muslim family. Born in Egypt, I was educated and am employed in Britain, and have been preoccupied and engaged, mainly in the 1960s and 1970s, with the issues that Mr Rushdie has fought for and with which he seemed to be very much concerned in his book.

Read the full article

Azerbaijan, the February 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

My decision

Salman Rushdie

February 1991, vol. 20, issue 2

A man’s spiritual choices are a matter of conscience, arrived at after deep. reflection and in the privacy of his heart. They are not easy matters to speak of publicly. I should like, however, to say something about my decision to affirm the two central tenets of Islam — the oneness of God and the genuineness of the prophecy of the Prophet Muhammad —and thus to enter into the body of Islam after a lifetime spent outside it. Although I come from a Muslim family background, I was never brought up as a believer, and was raised in an atmosphere of what is broadly known as secular humanism. I still have the deepest respect for these principles. However, as I think anyone who studies my work will accept, I have been engaging more and more with religious belief, its importance and power, ever since my first novel used the Sufi poem Conference of the Birds by Farid ud-din Attar as a model. The Satanic Verses itself, with its portrait of the conflicts between the material and spiritual worlds, is a mirror of the conflict within myself.

Read the full article

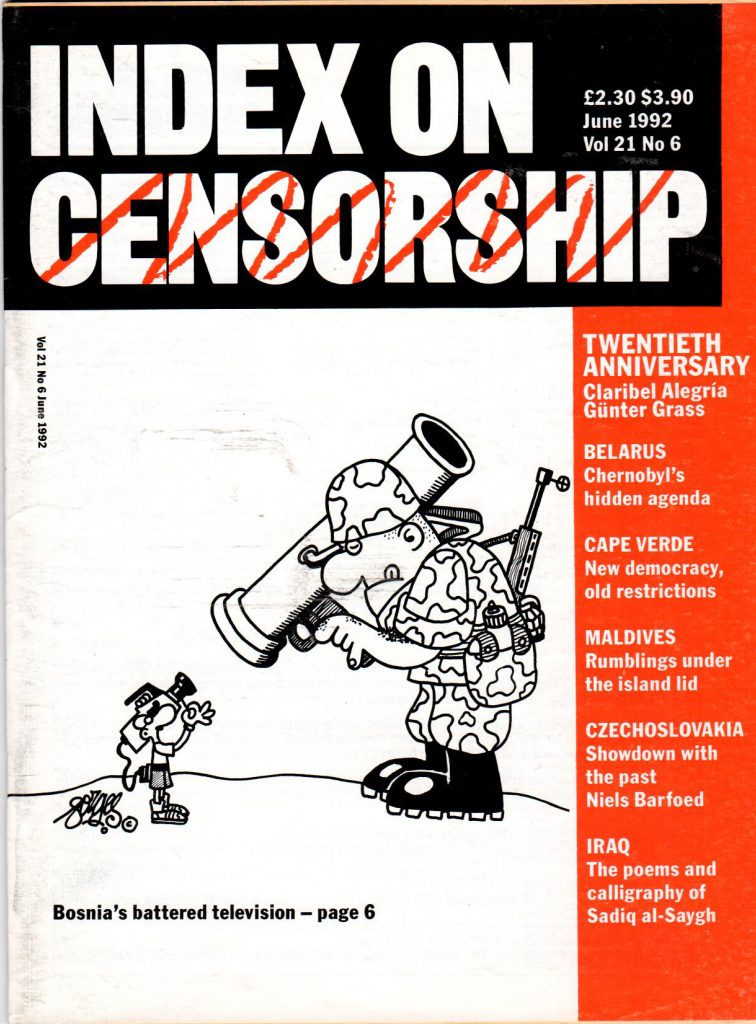

20th Anniversary: Reign of terror, the June 1992 issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Offending the high priests

Gunter Grass

June 1992, vol. 21, issue 6

When George Orwell returned from Spain in 1937, he brought with him the manuscript of Homage to Catalonia. It reflected the experiences he had gathered during the Civil War. At first, he was unable to find a publisher because a multitude of influential, left-wing intellectuals had no wish to acknowledge its shocking observations. They did not want to accept the Stalinist terror, the systematic liquidation of anarchists, Trotskyists and left-wing socialists. Orwell himself only narrowly escaped this terror. His stark accusations contradicted a world image of a flawless Soviet Union fighting against Fascism. Orwell’s report, this onslaught of terrible reality, tarnished the picture-book dream of Good and Evil. A year later, a bourgeois Western publisher brought out Homage to Catalonia; in the areas of Communist rule, Orwell’s works – among them the bitter Spanish truth – were banned for half a century. The minister responsible for state security= in the German Democratic Republic, right to its end, was Erich Mielke. During the Spanish Civil War, he was a member of the Communist cadre to whom purge through liquidation became commonplace. A fighter for Spain with an extraordinary capacity for survival.

Read the full article

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Russia’s choice, the November-December 1993 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The Rushdie affair: Outrage in Oslo

Hakon Harket

November 1993, vol. 22, issue 10

The terrorist state of Iran must face the consequences of refusing to lift the fatwa that condemns Salman Rushdie, and those associated with his work, to death. When someone, in accordance with the express order of the fatwa, attempts to murder one of the damned, the obvious consequence is that Iran must be held responsible for the crime it has called for, at least until there is conclusive proof that no connection exists. The shooting of William Nygaard has reminded the Norwegian public of what the Rushdie affair is really about: life and death; the abuse of religion; the fiction of a free mind. This war of terror against freedom of speech is not one we can afford to lose. Since the nightmare clearly will not disappear of its own accord, it must be engaged head-on.

Read the full article

New censors, the March 1996 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

From Salman Rushdie

March 1996, vol. 25, issue 2

This statement is not, of course, addressed to the Ayatollah Khomeini who, except for a handful of fanatics, is easily diagnosed as a sick and dangerous man who has long forgotten the fundamental tenets of Islam. It is useful to address oneself, at this point, only to the real Islamic faithful who, in their hearts, recognise the awful truth about their erratic Imam and the threat he poses not only to the continuing acceptance of Islam among people of all religions and faiths but to the universal brotherhood of man, no matter the differing colorations of their piety. Will Salman Rushdie die? He shall not. But if he does, let the fanatic defenders of Khomeini’s brand of Islam understand this: The work for which he is now threatened will become a household icon within even the remnant lifetime of the Ayatollah. Writers, cineastes, dramatists will disseminate its contents in every known medium and in some new ones as yet unthought of.

Read the full article

Shadow of the Fatwa

Kenan Malik

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

The Satanic Verses was, Salman Rushdie said in an interview before publication, a novel about ‘migration, metamorphosis, divided selves, love, death’. It was also a satire on Islam, ‘a serious attempt’, in his words, ‘to write about religion and revelation from the point of view of a secular person’. For some that was unacceptable, turning the novel into ‘an inferior piece of hate literature’ as the British-Muslim philosopher Shabbir Akhtar put it. Within a month, The Satanic Verses had been banned in Rushdie’s native India, after protests from Islamic radicals. By the end of the year, protesters had burnt a copy of the novel on the streets of Bolton, in northern England. And then, on 14 February 1989, came the event that transformed the Rushdie affair – Ayatollah Khomeini issued his fatwa.’I inform all zealous Muslims of the world,’ proclaimed Iran’s spiritual leader, ‘that the author of the book entitled The Satanic Verses – which has been compiled, printed and published in opposition to Islam, the prophet and the Quran – and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its contents are sentenced to death.’

Read the full article

The right to publish

The right to publish

Peter Mayer

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

As publisher of The Satanic Verses, Peter Mayer was on the front line. He writes here for the first time about an unprecedented crisis:

Penguin published Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses six months before Ayatollah Khomeini issues his fatwa. When we decided to continue publishing the novel in the aftermath, extraordinary pressures were focused on our company, based on fears for the author’s life and for the lives of everyone at Penguin around the world. This extended from Penguin’s management to editorial, warehouse, transport, administrative staff, the personnel in our bookshops and many others. The long-term political implications of that early signal regarding free speech in culturally diverse societies were not yet apparent to many when the Ayatollah, speaking not only for Iran but, seemingly, for all of Islam, issued his religious proclaimation.

Read the full article

Emblem of darkness

Emblem of darkness

Bernard-Henri Lévy

December 2008, vol. 37, issue 4

As publisher of The Satanic Verses, Peter Mayer was on the front line. He writes here for the first time about an unprecedented crisis:

Salman Rushdie was not yet the great man of letters that he has since become. He and I are, though, pretty much the same age. We share a passion for India and Pakistan, as well as the uncommon privilege of having known and written about Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (Rushdie in Shame; I in Les Indes Rouges), the father of Benazir, former prime minister of Pakistan, executed ten years earlier in 1979 by General Zia. I had been watching from a distance, with infinite curiosity, the trajectory of this almost exact contemporary. One day, in February 1989, at the end of the afternoon, as I sat in a cafe in the South of France, in Saint Paul de Vence, with the French actor Yves Montand, sipping an orangeade, I heard the news: Ayatollah Khomeini, himself with only a few months to live, had just issued a fatwa, in which he condemned as an apostate the author of The Satanic Verses and invited all Muslims the world over to carry out the sentence, without delay.

Read the full article[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1623240200822-8c1bcd36-9835-10″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]