27 Apr 23 | Burma, FEATURED: Jemimah Steinfield

There is a common misconception, even held by media editors, that Myanmar is just a military country now and that’s the end of its story. And yet this couldn’t be further from the truth, says Oliver Slow. The journalist, who lived in Myanmar between 2012 and 2020, tells Index that people in Myanmar have "got a taste of democracy".

"They want to at least have a free choice in their matters, they don’t want to be controlled by this very violent military, they want to have leaders who they have chosen for themselves," he says.

Slow is talking to Index in light of his newly released book Return of the Junta: Why Myanmar's military must go back to the barracks, an excerpt of which is featured below. For Slow, getting across this message is one of his hopes for the book. As he says, he wants everyone “to not give up on Myanmar, to understand that there is a vibrant future there."

Return of the Junta blends first-hand accounts with wider research into the background of the military. The result is an accessible, informed read on the 2021 coup d'état, and ultimately on this very complex country. While there are lighter moments in the book, it is not a sugar-coated retelling. Struggle for basic rights – nay survival – is a constant and unifying thread.

Early on Slow writes about how doctors have been a primary target of repression, persecuted in large part because they were central to the civil disobedience movement that formed in the immediate aftermath of the coup.

"That angered the regime and they decided essentially that they would punish doctors in many ways," Slow tells Index. "I remember from the time some pretty horrendous videos of soldiers just beating doctors in the streets." He says that when a third wave of Covid hit a few months after the coup the authorities would call doctors out to what they described as bad cases of Covid only to then arrest them.

Slow says "it speaks to the violence of the Myanmar military that doctors were specifically targeted" and shows "their lack of respect for international norms".

Such violence against doctors not only punishes them, it punishes the population more broadly. Two years on hospitals are in a parlous state in Myanmar. Doctors have fled.

"There is this feeling that they don’t want to work for any institution which aligns with the military," says Slow. A friend of Slow’s who recently visited a hospital in central Yangon described the conditions as “horrendous”.

Slow – who wouldn’t return to Myanmar right now because it would be too risky – finds it tougher and tougher to communicate with people there. "Most of my contacts have left because they’re journalists." Instead Slow relies on secure messaging apps to reach people on the ground.

According to Slow the main resistance is in the form of armed militia in the border areas. Many of the people in these militia were university students in 2021 and were enraged over the disappearance of their promising future. He says these militia are making some advances.

Of course it’s not just in the border regions that protest exists. On the anniversary of the coup this year Twitter was filled with images of a silent protest - streets of towns and cities across Myanmar were empty as people stayed at home to make a statement. There are also flash protests, very short protests where people “walk through the streets, do a photo, it goes on social media, they’re usually wearing a mask (for obvious reasons) and then they disband."

These anecdotes, combined with rising discontent over the military, give Slow hope.

"Can the military ever rule again in that country with any legitimacy? It’s a resounding no. Whether that means the resistance will win is a different matter as the military has made itself powerful over 50-60 years. The resistance is up against a pretty monumental machine," he says before adding:

"But I do see a time at some point in the future where the military will be defeated or removed from power.”

Excerpt from Return of the Junta

Despite the increased investment, even in pre-coup Myanmar life was still incredibly difficult for most teachers, especially those living in rural areas.

Myat Kyaw Thein is a secondary school teacher close to the town of Monywa, in central Myanmar.

“We have so many things to worry about as teachers, especially our safety and salary,” said Myat Kyaw Thein, who told me in an interview conducted before the coup that he earned the equivalent of about US$150 per month. “It’s not enough, especially when you compare it with other countries in Southeast Asia. No wonder so many people leave teaching to go to better paying jobs.”

“It’s a rotten salary, but whenever we raise it with authorities, they tell us it’s because of the low budget for education. Well, if you want to improve the education in this country, then increase the budget,” he said.

A similar story was told by a teacher in a remote village of Myanmar’s Nagaland. The teacher had worked at a school in her local village for more than ten years, and although the resources had improved in recent years, life was still difficult for her and her colleagues. She told me they often used their own money to provide things such as pens and books for their students.

“It’s difficult for us because we don’t have much salary, and sometimes have to use our family’s [money],” she said. “But then we want [the students] to be happy and to come to school. That’s why we provide these things for them.”

Even before the coup, it was clear that those tasked with overhauling Myanmar’s education system had an unenviable task ahead of them, including bringing together the dozens of different stakeholders – national and foreign – involved in such a monumental task and forming a cohesive strategy that pleases everyone.

Even what some may regard as the successes of the past decade in terms of reforms to education did not please everyone. For example, a recognition by the government about the need to switch from a teacher to a child-centred approach was a welcome step for those hoping to encourage more critical thinking, but parents who have only ever been exposed to the former their entire lives were understandably sceptical.

‘When a parent passes a school and doesn’t hear students chanting in unison what the teacher has written on the board, they think, ‘What’s going on in there? They aren’t learning’”, said an educator involved in the reforms.

Since the coup, however, much of the progress made over the last decade or so in Myanmar’s education sector has gone swiftly into reverse. With many teachers refusing to work under this junta, and parents not wanting to send their children to schools – either due to legitimate security concerns or because they don’t want them taught under this regime – the SAC has resorted to many of the tactics of past military juntas to try and portray an image of normalcy in schools and universities.

Like in 1962 and 1988 it has closed universities and fired teachers not supportive of the coup. Thousands of teachers have been sacked, and hundreds jailed, for participating in the civil disobedience movement against the junta. To fill these teaching ranks, the military-controlled education ministry has encouraged applicants with lower qualifications to apply for jobs, and even been accused of dressing up army wives and female members of pro-military organizations in teachers’ uniforms and transporting them to schools. Like under the SLORC government [the military State Law and Order Restoration Council that ruled the country between 1988 and 1997], teachers have been sent on month-long ‘refresher courses’ where they are urged to ‘pay attention to the preservation of Myanmar culture and traditions’ as well as ‘speak and behave respectfully and to be disciplined’, almost certainly euphemisms to discourage teachers from imbibing any form of revolutionary thinking into their students.

Before the coup, despite some bumps, the general trajectory of the education system in Myanmar was on a positive path. The changes were also made largely free of the military’s sphere of influence, an indication of the potential Myanmar has as a whole if the Tatmadaw’s own interests are not directly threatened.

Like almost everything in Myanmar, however, the 2021 coup has created considerable concerns about what happens next. If the current situation continues, and the military manages to maintain an albeit loose grip on power, it is the next generation of young people in Myanmar, and others beyond that, who will be the ones to suffer the most, through a lack of investment, or care, in their education, a lack of capabilities to think critically and problem solve, and a lack of skills to prepare them for the working world. This could well manifest, as it has in the past, of creating a general feeling among the population that Myanmar’s remarkable diversity is something to be feared, not celebrated.

Return of the Junta was published by Bloomsbury in January 2023. Click here for more information on the book.

27 Apr 23 | Events, Kuwait

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image="121063" img_size="full" onclick="custom_link" link="https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/an-unlasting-home-tickets-622511838667"][vc_column_text]

In 2013, Kuwait’s parliament authorised a law that made blasphemy a capital crime. Although this decision was successfully vetoed by the Emir of Kuwait, it highlighted the precarious sanctity of freedom of speech in a religiously conservative country. In An Unlasting Home, Mai Al-Nakib imagines an alternative reality where this law comes to pass.

Join Mai Al-Nakib in conversation with Index on Censorship’s Katie Dancey-Downs as she discusses her debut novel’s approach to censorship and blasphemy in the Middle East. Described by Ira Mathur as ‘an exquisite discourse on the nature of freedom’, An Unlasting Home is out now in paperback and published by Saqi Books.

Meet the speakers

Mai Al-Nakib was born in Kuwait and spent the first six years of her life in London, Edinburgh and St. Louis, Missouri. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Brown University and is an associate professor of English and comparative literature at Kuwait University. Her academic research focuses on cultural politics in the Middle East, with a special emphasis on gender, cosmopolitanism and postcolonial issues. Her short-story collection, The Hidden Light of Objects, won the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s First Book Award in 2014, the first collection of short stories to do so.

Mai Al-Nakib was born in Kuwait and spent the first six years of her life in London, Edinburgh and St. Louis, Missouri. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Brown University and is an associate professor of English and comparative literature at Kuwait University. Her academic research focuses on cultural politics in the Middle East, with a special emphasis on gender, cosmopolitanism and postcolonial issues. Her short-story collection, The Hidden Light of Objects, won the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s First Book Award in 2014, the first collection of short stories to do so.

Her fiction has appeared in Ninth Letter, The First Line, After the Pause and The Markaz Review, and her occasional essays in World Literature Today, BLARB: Blog of The LA Review of Books, and on the BBC World Service, among others. She lives in Kuwait.

Katie Dancey-Downs is Assistant Editor at Index on Censorship. She has travelled the world to tell stories about people and the planet. She’s passionate about human rights, the environment, and culture, and has a particular interest in refugee rights. Katie has written for a range of publications, including HuffPost, i News, New Internationalist, Resurgence Magazine, Reader’s Digest, and Big Issue, and is the former co-editor of the Lush Times magazine. She has a degree in Drama and Theatre Arts from the University of Birmingham and an MA in Journalism from Bournemouth University, where she focused her research on the ethical storytelling of refugee issues.

Katie Dancey-Downs is Assistant Editor at Index on Censorship. She has travelled the world to tell stories about people and the planet. She’s passionate about human rights, the environment, and culture, and has a particular interest in refugee rights. Katie has written for a range of publications, including HuffPost, i News, New Internationalist, Resurgence Magazine, Reader’s Digest, and Big Issue, and is the former co-editor of the Lush Times magazine. She has a degree in Drama and Theatre Arts from the University of Birmingham and an MA in Journalism from Bournemouth University, where she focused her research on the ethical storytelling of refugee issues.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Tuesday 30 May 2023, 1.00-2.00pm BST

Where: Online

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Apr 23 | China, FEATURED: Francis Clarke, Hong Kong, News and features, United Kingdom

The UK government is failing to acknowledge a British citizen unfairly imprisoned in Hong Kong amid a wider targeting of journalists and pro-democracy campaigners in the city state, said the authors of a new report on issues of freedom in Hong Kong.

On Monday, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Hong Kong (APPG) met at Portcullis House, London, to discuss their new report, Inquiry into Media Freedom in Hong Kong: The case of Jimmy Lai and and Apple Daily, which offers a sobering look into the state of media freedoms in the once vibrant city. Index contributed to the report.

The session was headed by Baroness Bennett of Manor Caste, the joint chair of the APPG. Other speakers included Lai’s international lawyer, Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC, Baroness Helena Kennedy and Sebastian Lai, Jimmy Lai’s son.

One of the aims of the report is to provoke a response from the British government regarding Lai. A pro-democracy figure, media tycoon and British citizen, he is in a Hong Kong prison after sentencing for unauthorised assembly and fraud charges. In addition to these charges are more serious ones of violating Hong Kong’s national security law, which was passed in 2020. Six of his colleagues at Apple Daily, the newspaper founded by Lai, are also in jail charged under the national security laws.

Kennedy believes the case of Jimmy Lai should be treated as a political priority by the UK government not only because Lai is a British citizen, but also because of the the joint declaration that gives the UK a place in trying to guarantee the rights of people in Hong Kong.

She added: “It is the illegitimate use of law against a citizen by the government, and against the protection of media freedom and expression in Hong Kong.”

Lord Alton of Liverpool, a vice chair of the APPG, echoed Kennedy’s called for Magnitsky-style sanctions against allies of the Hong Kong authorities in the UK as further action is needed. “We have to go beyond sanctions, to freezing the assets and redeploying the resources of those who have been able to use London as a place for their activities,” he said.

Gallagher said the Hong Kong authorities have weaponised their laws to target pro-democracy campaigners and journalists in new ways. Gallagher, who represents Jimmy Lai, as well as Maria Ressa from the Philippines who was charged with tax evasion, says that this is a new tactic - trying to discredit them by painting them as bad people rather than using the more traditional tactic of defamation. “It’s straight from the dictators’ playbook," she said.

Kennedy echoed this by stating fraud and tax affair charges are common tactics used against journalists in Hong Kong before more serious charges are later served. They added that as a result of supporting Lai they've received a series of threats and intimidation from state actors.

Sebastian Lai said he is also a target for the Chinese authorities. He acknowledged international support regarding his father’s cause but expressed disappointment in the UK government’s attitude. He said: "The language the UK government has used has been nowhere close to what America has used for not only a British citizen, but my father.”

However, he did acknowledge thanks for Anne Marie Trevelyan, MP and Minister of State in the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, for meeting him.

Fiona O’ Brien, the UK bureau director of Reporters Without Borders (RSF), said it needed to be waved in the face of those in power, “along with journalists writing stories, lawyers pursuing legal routes and advocates in society. We need to continue to shine a light.”

The report can be found here.

26 Apr 23 | Afghanistan, China, Egypt, India, Iran, Italy, Peru, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Uncategorized, United States, Zimbabwe

The central theme of the Spring 2023 issue of Index is India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

After monitoring Modi’s rule since he was elected in 2014, Index decided to look deeper into the state of free expression inside the world’s largest democracy.

Index spoke to a number of journalists and authors from, or who live in, India; and discovered that on every marker of what a democracy should be, Modi’s India fails. The world is largely silent when it comes to Narendra Modi. Let’s change that.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text="Up front"][/vc_column][vc_column][vc_column_text]Can India survive more Modi?, by Jemimah Seinfeld: Nine years into his leadership the world has remained silent on Modi's failed democracy. It's time to turn up the temperature before it's too late.

The Index, by Mark Frary: The latest news from the free speech frontlines. Big impact elections, poignant words from the daughter of a jailed Tunisian opposition politician, and the potential US banning of Tik Tok.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text="Features"][/vc_column][vc_column][vc_column_text]Cultural amnesia in Cairo, by Nick Hilden: Artists are under attack in the Egyptian capital where signs of revolution are scrubbed from the street.

‘Crimea has turned into a concentration camp’, by Nariman Dzhelal: Exclusive essay from the leader of the Crimean Tatars, introduced by Ukranian author Andrey Kurkov.

Fighting information termination, by Jo-Ann Mort: How the USA's abortion information wars are being fought online.

A race to the bottom, by Simeon Tegel: Corruption is corroding the once-democratic Peru as people take to the streets.

When comics came out, by Sara Century: The landscape of expression that gave way to a new era of queer comics, and why the censors are still fighting back.

In Iran women’s bodies are the battleground, by Kamin Mohammadi: The recent protests, growing up in the Shah's Iran where women were told to de-robe, and the terrible u-turn after.

Face to face with Iran’s authorities, by Ramita Navai: The award-winning war correspondent tells Index's Mark Frary about the time she was detained in Tehran, what the current protests mean and her Homeland cameo.

Scope for truth, by Kaya Genç: The Turkish novelist visits a media organisation built on dissenting voices, just weeks before devastating earthquakes hit his homeland.

Ukraine’s media battleground, by Emily Couch: Two powerful examples of how fraught reporting on this country under siege has become.

Storytime is dragged into the guns row, by Francis Clarke: Relaxed gun laws and the rise of LGBTQ+ sentiment is silencing minority communities in the USA.

Those we must not leave behind, by Martin Bright: As the UK government has failed in its task to rescue Afghans, Index's editor at large speaks to members of a new Index network aiming to help those whose lives are in imminent danger.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text="Special report: Modi's India"][vc_column_text]Modi’s singular vision for India, by Salil Tripathi: India used to be a country for everyone. Now it's only for Hindus - and uncritical ones at that.

Blessed are the persecuted, by Hanan Zaffar: As Christians face an increasing number of attacks in India, the journalist speaks to people who have been targeted.

India’s Great Firewall, by Aishwarya Jagani: The vision of a 'digital India' has simply been a way for the authoritarian government to cement its control.

Stomping on India’s rights, by Marnie Duke: The members of the RSS are synonymous with Modi. Who are they, and why are they so controversial?

Bollywood’s Code Orange, by Debasish Roy Chowdhury: The Bollywood movie powerhouse has gone from being celebrated to being used as a tool for propaganda.

Bulldozing freedom, by Bilal Ahmad Pandow: Narendra Modi's rule in Jammu and Kashmir has seen buildings dismantled in line with people's broader rights.

Let’s talk about sex, by Mehk Chakraborty: In a country where sexual violence is abundant and sex education is taboo, the journalist explores the politics of pleasure in India.

Uncle is watching, by Anindita Ghose: The journalist and author shines a spotlight on the vigilantes in India who try to control women.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text="Comment"][vc_column_text]Keep calm and let Confucius Institutes carry on, by Kerry Brown: Banning Confucius Institutes will do nothing to stop Chinese soft power. It'll just cripple our ability to understand the country.

A papal precaution, by Robin Vose: Censorship on campus and taking lessons from the Catholic Church's doomed index of banned works.

The democratic federation stands strong, by Ruth Anderson: Putin's assault on freedoms continues but so too does the bravery of those fighting him.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text="Culture"][vc_column_text]Left behind and with no voice, by Lijia Zhang and Jemimah Steinfeld: China's children are told to keep quiet. The culture of silence goes right the way up.

Zimbabwe’s nervous condition, by Tsitsi Dangarembga: The Zimbabwean filmmaker and author tells Index's Katie Dancey-Downes about her home country's upcoming election, being arrested for a simple protest and her most liberating writing experience yet.

Statues within a plinth of their life, by Marc Nash: Can you imagine a world without statues? And what might fill those empty plinths? The London-based novelist talks to Index's Francis Clarke about his new short story, which creates exactly that.

Crimea’s feared dawn chorus, by Martin Bright: A new play takes audiences inside the homes and families of Crimean Tatars as they are rounded up.

From hijacker to media mogul, Soe Myint: The activist and journalist on keeping hope alive in Myanmar.

18 Apr 23 | Afghanistan, FEATURED: Francis Clarke, News and features

Last Thursday, human rights organisation Anotherway Now hosted a screening of the Sky News documentary ‘Defying the Taliban: women at war in Afghanistan’. This was followed by a panel discussion hosted by Index on Censorship’s Editor-at-large Martin Bright.

Part of the discussion challenged the British government to create a route for Afghan women to apply safely for asylum into the UK. Zehra Zaidi, from the advocacy group Action for Afghanistan, said people need to show they are taking up the issue with the government. She added: “We also need to show it’s not a vote loser. That it’s the right thing to do, and the compassionate thing to do. We must keep fighting.”

The first of three documentaries looking at the fight for women’s rights in the world’s most hostile environments, Special Correspondent Alex Crawford travelled to Afghanistan over a year after the Taliban takeover.

Despite being a country where women’s rights plummeted under one of the most oppressive regimes in the world, we saw young women training as gynaecologists and paediatricians, with higher-level education currently allowed for women. However, with secondary education banned for young girls and women, it’s clear this will be a rare sight in the future. With medics generally only treating their same sex in Afghanistan, a ticking time bomb awaits.

What was striking is how women operated in the underground. Crawford used her network of contacts to show us a hidden world, including a safe house in Kabul run by rights activist Mahbouba Seraj, who is a 2023 Nobel Peace Prize nominee. A rare refuge from the brutal world outside, Seraj explained she takes in abused women and girls from all over Afghanistan, adding: “The Taliban don’t want us to exist. That’s why there’s no schools or work, or why women shouldn’t be walking on the street.”

Seraj doesn’t fear the Taliban though. “I find it ridiculous, insulting and annoyingly childish. But am I scared? No”, she said.

A secret network of schools also operates across Kabul, run by volunteers who teach maths and English to a younger generation of girls.

We’re shown secret workshops where women make art out of weapons and bullets; and make beautiful dresses where they can artistically portray their tough situation. Proceeds are used to feed their families, but also gives the women the freedom to expose their treatment in a male-dominated society. However, the freedom to artistically express is no longer an option for Farida (not her real name), once one of Afghanistan’s most celebrated painters. She said: “The Taliban burnt my gallery and said you can’t work on (paint) the faces of women.

“It killed me. We are empty. Now we don’t have hopes, and we don’t have dreams.”

Postcards of artwork by Farida that was smuggled out of Afghanistan (source: Sky)

During the post-screening discussion, Crawford explained the Taliban’s hypocrisy as the official reason given for banning women from attending medical school is male/female segregation isn’t possible, but female-only medical schools are closed anyway.

Zahra Joya, an exiled Afghan journalist and founder of Rukhshana media, urged everybody to keep the conversation about Afghanistan alive after the screening. She said: “This film shows the full-scale war against women in Afghanistan. Keep them in your mind and speak up.”

Calling for a show of hands from the audience, Zaidi asked the audience if anybody knew there is currently no asylum route into the UK for Afghan women. “There is none!”, she exclaimed. “None of those women in the film can apply to the British government for asylum. Our petition alone in August had 470,000 signatures to prioritise Afghan women and girls.”

Zaidi believed the Afghanistan crisis is being purposely mixed up with the small boats’ crisis and "illegal" migration bill, so it won’t stand on its own as a genuine issue in the UK. To wrap up, she offered her dream encounter with the British home secretary.

“I like a challenge. I see myself sitting opposite Suella Braverman inviting Afghan refugees to the UK if it’s the last thing I do!”

14 Apr 23 | Ireland, Northern Ireland, Opinion, Ruth's blog, United Kingdom

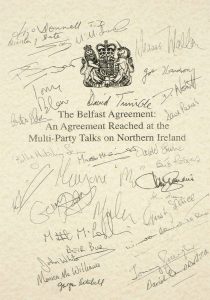

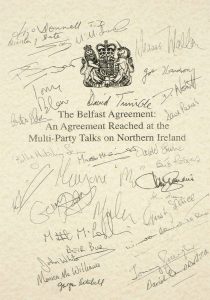

A copy of the Belfast Agreement signed by the main parties involved and organised by journalist Justine McCarthy of the Irish Independent newspaper. Photo: Whyte's Auctions

Every day the professional staff at Index meet to discuss what’s going on in the world and the issues that we need to address. Where has been the latest crisis? What do we need to be aware of in a specific country? Where are elections imminent? Do we have a source or a journalist in country and, if not, who do we know? During these meetings we are confronted with some of the worst heartbreak happening in the world. Journalists being murdered, dissidents arrested, activists threatened and beaten, academics intimidated and while we know that we are helping them by providing a platform to tell their stories it can be soul destroying to be confronted by the actions of tyrants and dictators every day.

Which is why grabbing hold of good news stories helps keep us on track. The moments when we’ve helped dissidents get to safety, when a tyrant loses, when an artist or writer or academic manages to get their work to us. These are good days and should be cherished for what they are - because candidly they are far too rare.

It’s in this spirit that I’ve absorbed every news article, reflection and op-ed column discussing events in Northern Ireland 25 years ago. I was born in 1979, my family lived in London - the Troubles were a normal part of the news. As I grew up, the sectarian war in Northern Ireland seemed intractable, peace a dream that was impossible to achieve. But through the power of politics, of words, of negotiation, peace was delivered not just for the people of Northern Ireland but for everyone affected by the Troubles. That isn’t to say it was easy, or straightforward and that it doesn’t remain fragile, but it has proven to be miraculous and is something that we should both celebrate and cherish.

The Good Friday Agreement delivered the opportunity of hope for the people of Northern Ireland. It gave us a pathway to build trust between communities and allowed, for the first time in generations, people to think about a different kind of future. For someone who firmly believes in the power of language, who values the world of diplomacy and fights every day for the protection of our core human rights there is no single moment in British history which embodies those values more than what happened on 10 April 1998.

We can only but hope that other seemingly intractable disputes continue to see what happened in Belfast on that fateful day as inspiration to challenge their own status quo.

14 Apr 23 | FEATURED: Mark Frary, India, News and features

India is a globally important market for the social media platform Twitter. Even though in absolute numbers its 23 to 24 million users is small compared to the size of the population of what is now thought to be the world’s most populous country, it is believed to be the platform’s third biggest market after the US and Japan.

Recent events relating to India and Twitter should therefore be taken in context of the country’s importance for Twitter’s owner, Elon Musk.

Even before Musk’s takeover of Twitter in October 2022, Narendra Modi’s government has not been slow to ask the platform to remove content which it disagrees with.

India has been in the top five nations that have asked Twitter to remove content or block accounts for the past three years. In its July 2022 transparency report, Twitter said that 97% of the total global volume of legal demands for such removals in the last half of 2021 originated from five countries: Japan, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, and India.

You could argue that because Twitter has so many users in the country, this is inevitable. However, the US does not feature in this list despite being the biggest market.

The Indian government clearly has a problem with what its critics are saying on Twitter.

In line with the worsening situation for media freedom in the country, India frequently clamps down on what the media is able to say on Twitter. In the last half of 2021, India was the country making the highest number of legal demands relating to the accounts of verified journalists and news outlets, some 114 out of a total of 326 for the period, comfortably ahead of Turkey and Russia.

A new onslaught on what Indians are saying on Twitter may have opened up last week. On 6 April, an amendment to India’s Information Technology Act came into force which now requires social media platforms to fact-check any post relating to the Indian government’s business with the Press Information Bureau, a “fact-checking” unit that is part of the country’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

The threat to social media platforms who do not comply with this is that they would then no longer be protected by the country’s safe harbour regulations under which they are currently not liable for what their users post.

The Indian digital liberties organisation Internet Freedom Foundation says it is “deeply concerned” by the amendments.

It said in a statement: “Assigning any unit of the government such arbitrary, overbroad powers to determine the authenticity of online content bypasses the principles of natural justice, thus making it an unconstitutional exercise. The notification of these amended rules cement the chilling effect on the fundamental right to speech and expression, particularly on news publishers, journalists, activists, etc.”

Twitter has long published details of how it handles requests from governments. In the event of a successful legal demand, such as a court order, Twitter follows these rules if it is required to delete individual tweets or an entire account. Typically these rules relate to a single country.

Under Musk’s ownership, these rules look as though they are changing.

Indian investigative journalist Saurav Das wrote recently about discovering that a number of his tweets had been removed and that they were not available worldwide. He told Scroll.In that tweets relating to Union Home Minister Amit Shah had been removed worldwide, not just in India.

The tweets seem relatively benign, although Das says he cannot remember exactly the context around posting them.

Tweeting on 9 April in response Das said, “Can Twitter allow the Indian government to sit in judgement over content that it may deem fit for blocking in America, or any other country apart from India?”.

He added, “If this global restriction of content on behest of a country’s govt is ignored, this will open a whole new chapter of censorship and prove disastrous for free speech and expression.”

Twitter's actions seem to fly in the face of its stated policy - pre-Musk ownership - towards India. In 2021, Twitter said that it would only block content and accounts within India and said it would not do so for “news media entities, journalists, activists, and politicians”. That scope now appears to have changed.

I asked Twitter’s press team for a statement on the case and received an automated email containing just a poop emoji. This has been a common response from Twitter’s press email since Elon Musk’s takeover, when the press team was significantly reduced.

During Elon Musk’s surprise interview with the BBC this week, Musk was asked about the issue of censorship of social media in India in the wake of the country banning the BBC's documentary on Narendra Modi. Musk said: “The rules in India for what can appear on social media are quite strict, and we can’t go beyond the laws of a country…if we have a choice of either our people go to prison or we comply with the laws, we’ll comply with the laws.”

14 Apr 23 | India, News and features, Volume 52.01 Spring 2023, Volume 52.01 Spring 2023 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image="120972" img_size="full" add_caption="yes"][vc_column_text]Recent estimates suggest that India has now overtaken China in population size, but where the world's most populated country should be a beacon of democracy, the opposite may be true.

Under Narendra Modi, the press is being strangled; the judiciary is no longer independent; and protesters are thrown in jail. You can read more about this in our forthcoming Spring 2023 issue, where our Special Report focuses on the state of free expression in Modi’s India.

In the meantime, here is a quiz to get a flavour of what to expect.

[streamquiz id="9"][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

07 Apr 23 | Afghanistan, FEATURED: Katie Dancey-Downes, News and features

“Every single day, the situation is intensifying,” Zan Times editor-in-chief Zahra Nader told an audience this week. Along with Afghan Witness and the Centre for Information Resilience, the Zan Times editor shone a spotlight on the experiences of Afghan reporters with the online event Discrimination, Prohibition and Perseverance: The Reality for Female Journalists in Afghanistan.

Nader started her journalism career in Kabul, but now lives in Canada. From there, she is not only an Index contributor, but also runs Zan Times, a women-led investigative newsroom focused on human rights violations in Afghanistan. She works with journalists in the country who all use pseudonyms, as well as others outside the country.

“Our aim is to report and tell the truth,” she said. She wants to put the power into the hands of women, so that “they define news”.

The laws that prevent women reporting effectively are not always specific to female journalists, she explained. They are impacted by the intersection of being female and of being a journalist. The Taliban issued decrees that women are not allowed to travel alone, that TV presenters and guests must cover their faces, and in some provinces that their voices cannot be heard on the radio. Travelling to meet sources suddenly becomes impossible, while radio presenters and other female voices are silenced in places like Kandahar, where women have been told they cannot phone into radio stations.

Nader explained how journalists in general, female or not, are forbidden from publishing anything contrary to Afghan culture or Islam. The Taliban has a strangling hold on media policy. She described a landscape where the Taliban has tortured people for covering women’s protests, and where more than half of media outlets have closed down due to a lack of funding or the impossibility of working within Taliban restrictions. The Taliban recently closed a women-run radio station in Badakhshan, and Nader is doubtful that any woman-owned media remains.

“The possibility of them to function seems very low,” she said.

Nader also suggested that for media organisations, “the Taliban vice and virtue would knock on their door everyday” is they hired female journalists, assessing what they were wearing and doing. She has heard reports of some organisations telling women that if they want to work as a journalist, they must do so without pay.

“Women are the main target of the Taliban,” she said, asking who, without female journalists, will platform women’s voices.

“The traditional classic work we used to do in Afghanistan no longer functions,” she said, explaining that new ways of reporting are needed, including offering women cyber security training to minimise risk, which is were working with organisations like Afghan Witness comes into play.

Afghan Witness’s Anouk Theunissen works from outside the country with open-source reporting and citizen journalism to de-bunk Taliban narratives. She explained that in the days since the Taliban takeover, online hate speech against women has increased significantly.

“As women have been erased from society, they have taken to social media,” she said. There, they can speak out more freely. But female journalists are beset with hateful comments and messages. Nader recalled one particular instance where a male journalist commented on a post, calling the abuse of women fake news.

Both Nader and Theunissen are doubtful about the situation in Afghanistan improving. What is missing, Nader said, is solidarity from the international community.

For women still working as journalists in Afghanistan, safety is paramount. Nader explained that rather than putting all their Afghan journalists in one WhatsApp group, Zan Times editors keep each conversation separate. Otherwise, if one journalist is arrested and their phone checked, all will be at risk.

Female journalists are forced to work remotely as much as possible for their own safety, and Zan Times advises them to only speak to sources who they can be sure are not linked to the Taliban. Any time they tell someone they’re a journalist, they risk being identified.

Some of Nader’s colleagues on the ground describe leaving their homes and wondering if that is the day they will be arrested, and yet they continue to go out.

“That gives me a little bit of hope, when they are still resisting,” she said. “That resistance might just be keeping the hope alive.”

06 Apr 23 | Events, India

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image="120980" img_size="full" onclick="custom_link" link="https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/democracy-at-deaths-door-in-modis-india-tickets-611126414557"][vc_column_text]

As India becomes the world’s largest nation it should be the world’s largest democracy. But was India ever a real democracy? If it was, how is it being threatened under current leader Narendra Modi? And what does the word democracy even mean?

In its 76th year since independence India will go to the polls next year. Modi is hugely popular and is tipped to win. But under his leadership the press, once vibrant, is being strangled, the judiciary is no longer independent, laws have been amended to throw protestors in jail, opposition figures are harassed, and minorities live in fear. While the global attention is focused elsewhere, Indians are fighting to protect their human and civil rights.

What can be done to protect the rights of minorities in India? What will Modi’s priorities be ahead of the 2024 elections? And crucially just how resilient is Indian democracy and is it open to everyone? The newest edition of Index on Censorship magazine explores these questions as we examine the role of free expression in contemporary Indian society. To launch the issue join us for an animated online panel discussion about past, present and future challenges to India’s democracy.

Meet the speakers

Salil Tripathi is an award-winning journalist born in Bombay and living in New York. He has written three works of non-fiction - Offence: The Hindu Case, about Hindu nationalist attacks on free expression, The Colonel Who Would Not Repent, about the war of independence in Bangladesh, and a collection of travel essays. He is writing a book on Gujaratis. More recently, he co-edited (with the artist Shilpa Gupta) an anthology honouring imprisoned poets over the centuries. He has been a correspondent in India and Southeast Asia. He was chair of the Writers in Prison Committee at PEN International and is now a member of its international board. He has studied in India and the United States and lived in the UK.

Dr Maya Tudor is an Associate Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford. She researches the origins of effective and democratic states with a regional focus on South Asia. She is the author of two books, The Promise of Power: The Origins of Democracy in India and Autocracy in Pakistan (2013) and Varieties of Nationalism (with Harris Mylonas, 2023 Forthcoming). She writes for the media on a regular basis, including in Foreign Affairs, Washington Post, New Statesman, The Hindu, India Express, and The Scotsman.

Hanan Zaffar is a journalist and film maker based in South Asia. He reports on Indian minorities and politics. His work has appeared in Time Magazine, VICE, Al Jazeera, DW News, Newsweek, TRT World, Channel 4, Middle East Eye, The Diplomat, and other notable media outlets.

Jemimah Steinfeld is editor-in-chief at Index on Censorship. She has lived and worked in both Shanghai and Beijing where she has written on a wide range of topics, with a particular focus on youth culture, gender and censorship.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Wednesday 3 May 2023, 2.00-3.00pm BST

Where: Online

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

05 Apr 23 | Egypt, News and features

If Priscilla Chan, an American citizen and wife of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerburg, was passing through Cairo International Airport and was stopped by a police officer who searched her phone illegally would she file a lawsuit? Possibly.

If Priscilla and her husband were Egyptian then the answer is definitely not. It is common knowledge that in Egypt, the police are above the law. If this hypothetical situation actually came to pass, I would advise Mark Zuckerburg not to run any social media campaigns publicising what happened with his wife because he would either be arrested or forcibly disappeared. Even if our hypothetical Egyptian Mark Zuckerberg managed to flee the country after that, he wouldn’t be able to create a campaign to help those in similar dangers -Facebook only allows political campaigns for those physically inside the country. If he managed to seek help from a friend or family member inside Egypt, then they will also likely be arrested immediately; Facebook's policy now requires someone’s full name in order to make a political campaign or advertisement. Thus, my advice to you my friend would be to internalise your anger. Facebook’s policies aid and abet tyrants. That is what Egyptians must face.

In 2017, the executive boards of Facebook, Twitter, and Google all announced that they found Russian hackers had bought ads on their platforms and used fake names a year previously to create controversial stories and spread fake news ahead of the American presidential elections of 2016. The companies handed over three thousand divisive ads to the US Congress, which they believed were bought by Russian parties in the months leading up to the elections in order to influence the outcome.

Between them, the tech companies appointed more than a thousand employees to review ads to ensure they are consistent with their terms and conditions and prevent misleading content. This was intended to deter Russia and others from using their social networks to interfere in the elections of other nations.

This led to Mark Zuckerburg’s announcement that outlined steps to help prevent network manipulation, including imposing more transparency on political and social ads that appear on Facebook. This included making advertisers provide identifying documentation for political, social and election-related ads. Likewise, he announced that the advertisements would have to bear the name of the person that funded the advertisement, and that the predominant funder of the advertisement must reside in the country itself, and the financing must be done locally.

I find that there is a significant gap between the reality of what is truly happening in the Middle East and what the West understands about it. What is happening in Egypt specifically is not comparable to anything happening in the US or Europe and thus the international policies for such companies cannot be developed based on the desires and needs of only the American public.

These laws were supposed to help American society be more transparent but instead are being used as a weapon by the Egyptian regime in order to crack down on people's rights and freedoms and they put human rights activists in Egypt in further danger.

Revealing the full names of those creating political or human rights campaigns leads to these individuals being constantly under threat, of both their posts being taken down and a potential government crackdown on them. As a result, these laws become a means of control for the government to further silence the voices of the masses. We, as human rights defenders in Egypt, need security and privacy, as the nature of our work exposes violations within systems and governments. There are a large number of risks that we are already exposed to daily because of our activity, and it is possible to monitor us in many ways, including the digital system, in which the system can currently determine all our activity through such transparency laws.

We are not looking for equal rights or to enter elections, rather we are merely attempting to possess our own humanity, preserve our dignity, and stand up for our rights. We dedicate our lives for equality and to prevent infringements on the rights of those in our society. Now that our activism is deemed nearly impossible by your laws, Mr Zuckerburg, you truly leave us with no option as we cannot put our families and communities at risk of imprisonment due to our names and the names of those helping us being made available.

I urge you to make digital privacy and security of human rights defenders a top priority, as today these activists have become truly vulnerable to repressive tactics as the Egyptian regime uses your laws as a loophole to remove opposition.

We have already had bad experiences with your laws.

Human rights defender Sherif Alrouby has been imprisoned by the Egyptian regime for years and we attempted to campaign for his release. We tried to spread a song entitled ‘Sherif Alrouby is imprisoned oh country’ and were impeded by Facebook's policies. We had no option but to stop our campaign in order to prevent any security issues with the individuals that funded our advertisement as their full names were displayed.

Facebook's policies impede our work as human rights defenders. We recognize that you support freedom of speech and desire increased transparency, but you do not realise the severity of what is happening in Egypt. A prime example of the severity of the situation is the killing of activist Shady Habash inside prison for merely making a song criticising the regime's policies during the reign of El-Sisi. Likewise, my friend Galal El Behiery spent more than six years in prison for writing the song’s words - he has been on hunger strike in prison for more than 14 days.

I urge you all to understand the differences between nations. Egypt is not a transparent nation. Rather, it is an oppressive nation that exploits transparency to kill and dispose of opposition.

31 Mar 23 | FEATURED: Mark Frary, News and features, Saudi Arabia

Salma is one of many Saudi prisoners of conscience to go on hunger strike

Salma al-Shehab, a 34-year-old mother of two and former PhD student at the University of Leeds, who in 2021 was handed a 34-year-long jail sentence for tweeting her support for women’s human rights defenders in her native Saudi Arabia, has gone on hunger strike.

Salma was arrested in January 2021 while on a visit home from the UK to see her family. She then faced months of interrogation over her activity on Twitter.

In March 2022 she was sentenced to six years in prison by the country’s Specialized Criminal Court (SCC) under the vague wording of the country’s Counter-Terrorism Law, but this was increased on appeal to an unprecedented 34-year term followed by a 34-year travel ban.

The SCC was originally established to try terrorism cases but its remit has widened to cover people who speak out against human rights violations in the country. Salma is one of a number of people tried by the SCC who have been handed farcically long sentences for simply expressing their human rights. The SCC is the main tool with which Saudi Arabia has effectively criminalised freedom of expression.

In January this year, Salma’s sentence was reduced to 27 years after a retrial was ordered. During the retrial, the presiding judge denied Salma the right to speak in her defence.

Salma has been joined on hunger strike by seven other prisoners of conscience, who have been handed jail terms longer than those which would be handed out to hijackers threatening to bomb a plane.

In Saudi Arabia, prisoners of conscience often go on hunger strike to protest their treatment. Those resorting to this include women’s rights activist Loujain Al-Hathloul, the blogger Raif Badawi, the academic and human rights defender Mohammad al-Qahtani, the writer Muhammad al-Hudayf and the lawyer Walid Abu al-Khair.

ALQST’s head of monitoring and advocacy, Lina Alhathloul, the sister of Loujain, said: "Knowing how harshly the Saudi authorities respond to hunger strikes, these women are taking an incredibly brave stand against the multiple injustices they have faced. When your only way of protesting is to risk your life by refusing to eat, one can only imagine the inhumane conditions al-Shehab and the others are having to endure in their cells.”

ALQST says that in previous hunger strikes, prison officials often wait several days before taking any action. “When they have eventually acted, it has been to threaten the prisoners with punishment if they continue their strike, and then place them in solitary confinement in dire conditions, subjecting them to invasive medical examinations and threatening to force-feed them. Phone calls, visitors and activities are also denied, in an attempt to coerce prisoners to end their hunger strikes,” the organisation said.

Salma and her fellow hunger strikers should never have been arrested and jailed in the first place for simply exercising freedom of expression that people take for granted in countries other than Saudi Arabia. They should have their sentences quashed and released from prison immediately.

Mai Al-Nakib was born in Kuwait and spent the first six years of her life in London, Edinburgh and St. Louis, Missouri. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Brown University and is an associate professor of English and comparative literature at Kuwait University. Her academic research focuses on cultural politics in the Middle East, with a special emphasis on gender, cosmopolitanism and postcolonial issues. Her short-story collection, The Hidden Light of Objects, won the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s First Book Award in 2014, the first collection of short stories to do so.

Mai Al-Nakib was born in Kuwait and spent the first six years of her life in London, Edinburgh and St. Louis, Missouri. She holds a Ph.D. in English from Brown University and is an associate professor of English and comparative literature at Kuwait University. Her academic research focuses on cultural politics in the Middle East, with a special emphasis on gender, cosmopolitanism and postcolonial issues. Her short-story collection, The Hidden Light of Objects, won the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s First Book Award in 2014, the first collection of short stories to do so. Katie Dancey-Downs is Assistant Editor at Index on Censorship. She has travelled the world to tell stories about people and the planet. She’s passionate about human rights, the environment, and culture, and has a particular interest in refugee rights. Katie has written for a range of publications, including HuffPost, i News, New Internationalist, Resurgence Magazine, Reader’s Digest, and Big Issue, and is the former co-editor of the Lush Times magazine. She has a degree in Drama and Theatre Arts from the University of Birmingham and an MA in Journalism from Bournemouth University, where she focused her research on the ethical storytelling of refugee issues.

Katie Dancey-Downs is Assistant Editor at Index on Censorship. She has travelled the world to tell stories about people and the planet. She’s passionate about human rights, the environment, and culture, and has a particular interest in refugee rights. Katie has written for a range of publications, including HuffPost, i News, New Internationalist, Resurgence Magazine, Reader’s Digest, and Big Issue, and is the former co-editor of the Lush Times magazine. She has a degree in Drama and Theatre Arts from the University of Birmingham and an MA in Journalism from Bournemouth University, where she focused her research on the ethical storytelling of refugee issues.