15 Nov 21 | China, Hong Kong, News and features

A former food delivery worker calling himself a “second-generation Captain America” and who would turn up at protests in Hong Kong with the Marvel superhero’s instantly recognisable shield has been convicted for violating the country’s national security law (NSL).

On 11 November, Adam Ma Chun-man was sentenced to five years and nine months for inciting secession by chanting pro-independence slogans in public places between August and November 2020.

Evidence cited by a government prosecutor in the court case against Ma included calls for independence he had made in interviews.

Ma becomes the second person to be found guilty under the law imposed by Beijing in July last year. He has lodged an appeal against the verdict.

The first person sentenced under the NSL was former waiter Tong Ying-kit who was jailed in late July for nine years for terrorist activities and inciting secession. Tong was accused of driving his motorcycle into three riot police on 1 July 2020 while carrying a flag with the protest slogan “Liberate Hong Kong. Revolution of our times.”

The watershed ruling on Tong has profound implications for freedom of expression and judicial independence in Hong Kong.

The “Captain America” case has further fuelled fears about the rapid erosion of the city’s room for freedom and the strength of the court in upholding civil liberties.

Like the Tong case, the Ma judgement has significant implications for related cases but the ruling has attracted far less attention. The general public reacted with indifference mixed with a feeling of futility and helplessness. It does not bode well for civil rights and liberties in the city.

The significance of the Ma case lies with the judge’s ruling on what constituted incitement.

Ma’s lawyer said Ma had no intention whatsoever of committing a crime, but was just expressing his views. Merely chanting slogans should not be deemed as a violation of the NSL, the lawyer argued. That he urged people to discuss the issue of independence in schools did not necessarily mean the result of the discussions would be a yes to independence. It could be a no.

Importantly, his lawyer argued Ma had merely expressed his personal views without giving thought of how to make it happen through an action plan. Referring to Ma’s slogan “Hong Kong people building an army”, his lawyer said it was just an empty slogan, again, without a plan.

In sentencing, judge Stanley Chan described the case as serious. He rejected the argument by Ma’s lawyer that the level of incitement in his speeches was minimal, saying Ma could turn more people into the next Ma Chun-man.

Put simply, judge Chan said that although the actual impact of Ma’s speeches in inciting others has been minimal, this was insignificant when determining whether his act constituted incitement.

This view is markedly different from the reaction of the media and the public over Ma’s political antics.

Ma had drawn the attention of journalists when he turned up in protests for obvious reasons. But no more. The lone protester neither had a sizable group of followers nor electrified the sentiments of the crowd at the scene.

The heavy sentencing of Ma will worsen the chilling effect of the national security law on freedom of expression. Importantly, it will have serious implications for a list of incitement cases currently in the process of trial.

In a statement on the sentencing, Kyle Ward, Amnesty International’s deputy secretary general said: “In the warped political landscape of post-national security law Hong Kong, peacefully expressing a political stance and trying to get support from others is interpreted as ‘inciting subversion’ and punishable by years in jail.”

With no sign of an easing of the enforcement of the law 16 months after it took effect, the international human rights group decided to shut down its local and regional offices in the city by the end of the year. They said the Beijing-imposed law made it “effectively impossible” to do its work without fear of “serious reprisals” from the Government.

Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam responded by saying no organisation should be worried about the national security law if they are operating legally in Hong Kong, adding Hong Kong residents’ freedoms, including that of speech, association and assembly were guaranteed under Article 27 of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

To a lot of Hongkongers, the assurance, which is an integral part of the former British colony’s “one country, two systems” policy, is an empty promise.

The power of the national security law in curtailing freedoms in other aspects of everyday life in Hong Kong has been widely felt.

In October, the legislature rubber-stamped an amendment to the film censorship ordinance, giving powers to the authorities to ban films that are considered as “contrary to the interests of national security.” The phrase, or “red line” in the law, is much broader than the original version, which targeted anything that might “endanger national security.”

Even before the bill was passed, a number of films and documentary films relating to the 2019 protest were not allowed to be shown in public locally. They include the award-winning Inside the Red Brick Wall and Revolution of Our Times, a nominee in the 2021 Taiwan Golden Horse Film Award.

Moves to revive political censorship in film are part of the authorities’ intensified campaign against threats to national security. While targeting political activists, the net has been widened to curb what officials described as “soft confrontation” and “penetration” through films, art and culture and books.

The University of Hong Kong has called for the Pillar of Shame, a sculpture by Danish artist Jens Galschiot, to be removed from the campus, citing concern over the national security law.

On the legislative front, security minister Chris Tang has given clear reminders that more needs to be done to protect national security, pointing to crimes in Basic Law Article 23 that have not been covered in the national security law.

He has vowed to target spying activities and to plug loopholes following the social unrest in 2019. Tang cited the example that helmets and free MTR tickets were distributed free to protesters during the protests, claiming there were state-level organising behaviours, potentially by actors from outside the country.

Both the central and Hong Kong authorities have labelled the movement as a “colour revolution” with hostile foreign forces behind it, without giving concrete evidence.

In addition to spying, a bill on Article 23 will also cover theft of state secrets and links with foreign organisations. Officials gave no timetable. But it is expected to be at the top of the agenda for the new legislature, which is due to be formed after an election is held on 19 December.

Officials are also looking at introducing a law on “fake news” to eliminate what they deem as lies and disinformation, which went viral on social media during the 2019 protest. The Government and the Police claimed they were major victims of this false information.

Looking back to mid-2020 when the idea of a national security law was first mooted, officials assured Hongkongers the law would only “target a very small number of people”.

Nothing can be further from the truth.

12 Nov 21 | Brazil, Ruth's blog, Scotland, The climate crisis, United Kingdom

For the last fortnight the media has been dominated by news of the COP26 conference. We’ve lived and breathed, along with the negotiators, each aspect of a potential final deal to tackle climate change once and for all. We’ve listened to leaders discuss how as a global community we must limit the global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees and where the political will is and is not for comprehensive change.

We’ve heard from global leaders, from the G7 and the G20. From the UN, the Commonwealth and every possible global coalition. We’ve heard from former elected leaders, religious leaders, activists, local government leaders and financiers who have all had their say in an effort to push those with power to make life-changing decisions for all of us. Yet as I write we still don’t know what the final deal will really promise and what is likely to be achieved from two weeks of talking.

I believe that talking is incredibly important, diplomacy is the most powerful tool we can have and there are never enough words. But in this case, I worry not about who we have heard from and not even about what the final deal may look like (although we desperately need united action), but rather I am horrified about who we have not heard from.

In the midst of this geo-political strategic negotiation, we seem to have heard from every stakeholder, every country and even many companies. Who we’ve heard very little from however are the people on the frontline of this crisis. Of the indigenous peoples whose lands and livelihoods are at threat from floods or famine. People who have been silenced by their governments, for decades, as they attempted to raise the impacts of pollution and climate change to their communities. People who were attacked by their own governments and corporations for undermining economic development and therefore persecuted and silenced for telling the truth about what was happening to their land and their people.

As the world gathered, it is their voices, those of indigenous communities, which needed to be heard, that could and should have acted as a galvanising force – emotive but factual testimony about what is really at stake. Instead, indigenous peoples around the world have been silenced. The impact of climate change has resulted in a climate of fear. A double whammy for those on the front line of this climate change disaster. It is their stories which Index has highlighted during COP26. With the support of the Clifford Chance Foundation we’ve been able to help tell their stories – both in our magazine and online. So please, take a minute and read their stories as we all consider what we need to do to help fix the planet.

09 Nov 21 | Iran, News and features

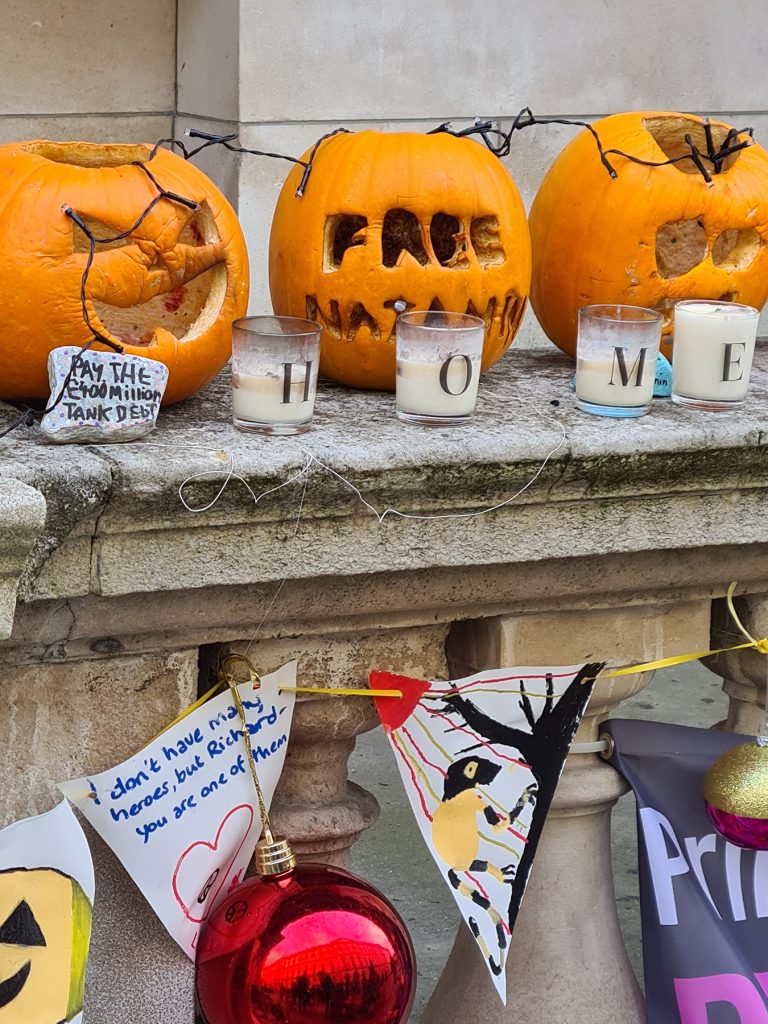

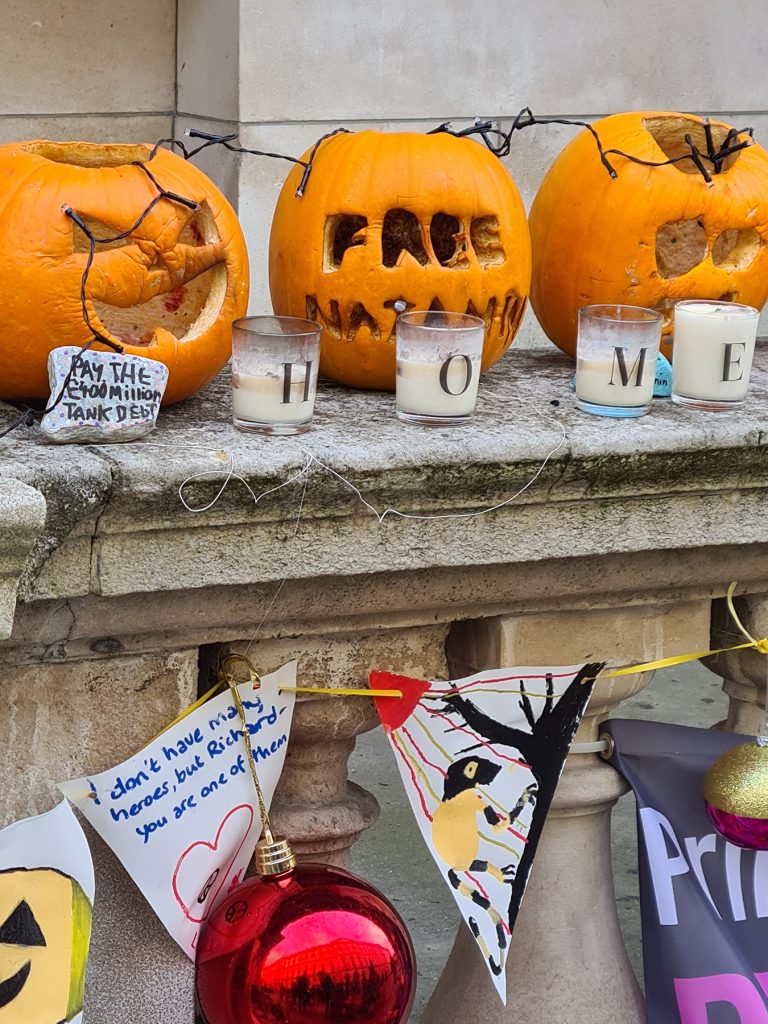

As Richard Ratcliffe enters day 16 of a hunger strike to protest against UK government inaction in the case of the continuing detention of his wife Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe in Iran, he says it is not the lack of food that is his biggest worry.

“It is the cold,” he says from his makeshift tent village outside the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall, just a short walk from the Houses of Parliament. Last Friday – Guy Fawkes Night – the mercury dipped to below freezing as a candlelit vigil was held to raise awareness of this wife’s plight, who has been detained in Iran for more than five years.

Nazanin, who was working for the Thomson Reuters Foundation at the time of her arrest, was sentenced to five years in prison in 2016 for “plotting to topple the Iranian regime”. As the end of her sentence approached, Nazanin was told she faced new charges of “propaganda activities against the government”. In April 2021, she was sentenced to a further year in prison. I spoke to Richard at the time in our podcast.

It is clear that Nazanin is clearly a pawn in a game of one-upmanship between the British and Iranian governments. There is no guarantee that she will be released even after serving the new sentence.

This is why Ratcliffe is carrying out his protest – to make the British government recognise that its strategy towards Iran has failed.

With his quilted jacket and woolly hat and mittens, Ratcliffe looks like many of the nearby rough sleepers. Yet few of those on nearby Whitehall are surrounded by pebbles painted by young children and carved pumpkins or have their tents festooned with fairy lights. Still fewer have a pile of Amazon deliveries from well-wishers.

With his quilted jacket and woolly hat and mittens, Ratcliffe looks like many of the nearby rough sleepers. Yet few of those on nearby Whitehall are surrounded by pebbles painted by young children and carved pumpkins or have their tents festooned with fairy lights. Still fewer have a pile of Amazon deliveries from well-wishers.

Camped out in the heart of British Government, Ratcliffe has been visited by a steady stream of MPs, including the Conservative MP for Ipswich Tom Hunt today.

This in itself is quite unusual.

“I have certainly been visited by more opposition MPS than those in the government,” says Ratcliffe. “I have had a lot of visits from the Labour front bench. Of those in the Government that did visit, very few wanted their picture taken.”

He has not been short of other well-known visitors wishing him well, including the author Kathy Lette, Victoria Coren and TV presenter Claudia Winkelman.

Ratcliffe says that despite promises from former Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, little seems to be happening in official channels to secure the release of his wife.

“There have been no negotiations of substance for a while,” he says.

As the light faded and the temperature dropped again tonight, Ratcliffe’s hunger strike continued. Many experts say that the human body can endure around 25 days without eating before permanent damage occurs.

Ratcliffe plans to continue while he can.

“One of the things I have heard from other hunger strikers is that you eventually start closing in on yourself. That hasn’t happened so far,” he says. “You have to listen to your body though.”

Richard’s family and friends are naturally worried for his well-being and many are taking it in turns to keep his spirits up. As I speak to him, his mum – resplendent in a multi-coloured coat that belies the seriousness of the situation – pops over with a hot water bottle to keep the cold at bay.

Despite the cold and the growing concern of the effects of not eating, Ratcliffe will remain outside the Foreign and Commonwealth Office for now and certainly until later this week when Iran’s vice president Dr Ali Salajegheh leaves the UK after attending COP26 in Glasgow.

When the Government’s focus turns away again from the global ecofest, it needs to think about how it deals with Iran.

He says, “I don’t think the Foreign Office understands Iran properly. The Government also needs to look long and hard at its hostage policy and its ineffectiveness.”

Ratcliffe is clear on one thing that would help secure Nazanin’s release – the British Government could pay the £450 million that Ratcliffe and many others believe say it owes to the Iranian government. The money was paid to the UK in the 1970s by the then Shah of Iran to buy Chieftain tanks and armoured vehicles. When the Shah was deposed, Britain sold the vehicles instead to Iraq but kept the money.

Sign the petition to Free Nazanin here and, if you are in the UK, write to your MP.

02 Nov 21 | News and features, The climate crisis, United States

Most Americans do not need to worry about the oil pipelines that fuel their cars, and most live with their water supplies comfortably distant from any risk of a spill. Yet indigenous communities in the USA cannot count on having clean drinking water because the country’s thirst for gas is fed by pipelines that cross their native lands.

Over the past decade, the construction of three such pipelines has been challenged by environmentalists and indigenous communities due to the risk to the environment and the violation of tribal sovereignty. The Dakota Access Pipeline, the Keystone XL Pipeline, and Line 3 each run through reservation land against the express wishes of the tribes the lands belong to.

The Keystone XL pipeline had its permit cancelled in June 2021 by president Joe Biden’s administration. Faith Spotted Eagle, a leading activist against the pipeline and a member of the Ihanktonwan Dakota nation, told The Guardian the executive order was “an act of courage and restorative justice by the Biden administration.” The pipeline had faced constant protest from environmental and indigenous groups in the 10 years since it had been proposed. The administration’s executive order stated that “the United States must be in a position to exercise vigorous climate leadership in order to achieve a significant increase in global climate action and put the world on a sustainable climate pathway.” But what is unclear is why this pipeline is different from any others.

A question of tribal sovereignty

In Minnesota, activists and community members are gathering in response to the Line 3 project that puts the water sources of three reservations—Leech Lake, Red Lake, and White Earth—at risk from oil spills and cuts through treaty land in violation of tribal sovereignty.

Tania Aubid, an elderly activist who grew up in treaty territory, carried out a 28-day hunger strike to protest the pipeline.

“It’s my future grandchildren and great grandchildren coming standing up to the pipeline… What I’m hoping for is to be able to have a healthier ecosystem for us to be able to live in,” she told the Stop Line 3 campaign.

Activists are calling for the government to take similar action against this pipeline. Winona LaDuke, an Ojibwe leader and Indigenous rights organiser who was arrested at a Line 3 protest and spent three nights in jail, told online magazine Slate: “Biden’s acting like he cancelled one pipeline so he gets a gold star. But you don’t get a gold star from Mother Earth to let Line 3 go ahead.”

She added: “It’s brutal up here. I’m watching a very destructive pipeline tearing through the heart of my territory. That’s why Joe Biden should care. Because it’s wrong.”

The pipeline is disrupting the watershed and traditional wild rice habitats.

A Canadian oil pipeline corporation, Enbridge, has proposed the expansion of Line 3, which was responsible for the worst inland oil spill in US history in 1991. The Biden administration, which is backing Trump-era approval for the pipeline, has turned down any requests for comment.

The Justice Department said the 2020 approval “met its … obligations by preparing environmental assessments” and asked the courts to reject any case brought against the project. This month, the Minnesota Supreme Court upheld state regulators’ approval of the project, and Enbridge says the pipeline is on track to be completed by the end of the year.

Five years since Standing Rock

If a year is a long time in politics, five years is almost an eternity.

In 2016, social media images from the protests at the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota and South Dakota shocked Americans. A grassroots movement against Energy Transfer Partners Dakota Access Pipeline caught the nation’s attention when activists stood against the construction of the pipeline, creating the single largest gathering of Native Americans in 100 years.

Protesters had to withstand police violence, including excessive use of pepper spray, water sprayed from high-pressure hoses, and attacks from police dogs. The pipeline was planned to run from North Dakota’s Bakken oil field to southern Illinois, crossing through the Standing Rock Reservation on the border of North Dakota and South Dakota and beneath their main water source, Lake Oahe.

Standing Rock is the sixth-largest Native American reservation and home to nearly 9,000 members of the Hunkpapa and Sihasapa bands of Lakota Oyate and the Ihunktuwona and Pabaksa bands of the Dakota Oyate. The community and independent experts believed that a potential rupture of the pipeline was a serious threat to the clean water supply. The path of construction cut through historically and religiously significant land. Finally, the pipeline would disrupt the reservation’s natural ecosystem.

This pipeline had been rerouted from crossing the Missouri River near Bismarck, North Dakota, a far wealthier, predominantly white community, over concerns about proximity to water sources and wetlands.

Youth and women’s groups from Standing Rock and surrounding communities organised a campaign to block the construction of the pipeline, using the hashtag #noDAPL on social media. “Water protectors” encamped around Standing Rock, creating protests that reached the size of a small city, in an attempt to block construction.

The Barack Obama administration halted the construction of the pipeline by executive order. However, in January 2017, the Trump administration issued an order allowing its resumption. The pipeline was completed in April 2017.

Capturing the mood

Ryan Vizzions began his independent photography career with the 2015 Black Lives Matter protests in Atlanta. When he heard about the #noDAPL protests, he saw the similarities with the civil rights movement. A planned four-day trip to cover it turned into a six-month commitment; he went back to Atlanta just long enough to quit his job and put all his belongings into storage so he could stay with the protests and help stop the pipeline. He captured the police violence in photos, but he also documented the camps which were “filled with song and prayer, ceremony and community”.

His images of Standing Rock capture the mistreatment of a community that so much of the USA has ignored. After his images of police violence went viral, money poured in from supporters, turning the camps into communities with enough resources to feed and house protesters.

Vizzons said that by winter, PTSD from the police violence was common throughout the camp and as national attention faded and temperatures dropped, people began leaving.

The community in the camp “was a beautiful moment in history”, he said, adding that what made Standing Rock different was how their voices reached their audience: “Mainstream media tried to avoid the Standing Rock movement until social media made it impossible. We were the news, not them and they hated it.”

Since the arrival of the first Europeans, North America’s indigenous people have been forced off their land and have had to watch as it has been urbanised. The further west mainstream settlements expanded, the more the government would push tribes further off their land by breaking treaty promises and committing or allowing grotesque violence against indigenous people.

Through physical force and economic manipulation, the government forced indigenous people onto the country’s most desolate lands in what is now the reservation system, and despite promises of tribal sovereignty on reservations, reservations still face exploitation and violation of land rights while lacking the political voice to stop the government or government-backed corporations.

The Standing Rock episode is one of the most notable modern instances of harassment and discrimination against the American indigenous population, but the struggle to be heard has long been part of being an indigenous person in the USA.

Seeking financial stability

Today, Standing Rock people live with the pipeline and continue the struggle to be heard by their local government and financial institutions. The community faces challenges for which it is less easy to rally support on social media, such as struggling to obtain bank loans or teen depression.

Joseph McNeil, Jr grew up in New York but moved back to his family’s home in Standing Rock 34 years ago. He has been a tribal council member and today is the general manager of Standing Rock’s wind farm organisation. Striving for energy and financial independence, the Standing Rock Renewable Energy Public Power Authority pursues wind power as a solution that is both green and affordable.

As general manager, McNeil and the authority prioritise balancing Standing Rock’s energy needs with environmental protection and climate justice, a fundamental belief that makes the existence of the Standing Rock pipeline untenable. The Standing Rock Council is also working to create a credit union to increase economic stability amongst the native people. With their renewable energy sources and a credit union, the goal is to deconstruct the two major ways their community is oppressed.

McNeil said the reservation faced the constant struggle of not having economic assets to pursue their business plans and grow the capital of the reservation. He described the institutional oppression the community faces, saying that “business and government are hand in glove.” The reservation system denies land ownership to residents, crippling them economically and politically.

“It’s hard to get a home loan if you have an address on the reservation,” said McNeil.

He described the psychological impact on his community: “The desperation…the kids didn’t have hope…they’ve seen the cycle of [financial] and emotional poverty”

The lack of opportunity on reservation and the racism they faced off it led to a rash of teen suicides 10 years ago and is a major motivation for the work to provide for the community, who live with the pipeline running through its land.

“I feel devalued when I turn the water on, I feel my kid’s lives are devalued,” said McNeil. “We fought it tooth and nail. We said no from day one.”

A lack of voice

Indigenous groups along the Line 3 route are hoping the same does not happen to them.

Earlier this year, activists started creating ceremonial lodges and resistance camps along the path of construction and some attempted to block the work by forming a human chain.

Just like at Standing Rock, the environmental impact report was rushed and incomplete, and police have been using similar aggressive techniques to those seen in 2016 in Standing Rock: rubber bullets, fire hoses, and police attack dogs.

The pipeline is nearing completion, and the three reservations are facing the timeless American practice of exploiting indigenous people’s lack of voice for the economic gains of mainstream culture.

Stop Line 3 has published its grievances against the pipeline.

Its construction is disrupting shrinking wild rice habitats. Meanwhile, over a 10-year period, according to the US Department of Transportation, an “average” pipeline has a 57% chance of spills.

Stop Line 3 also argues that the state of Minnesota does not have the consent of the tribes or jurisdiction over tribal land and therefore it is a violation of tribal sovereignty and what the organisation calls “modern-day colonialism”.

“The phrase ‘new oil pipeline’ should not even be in our vocabulary,” it argues because the overwhelming consensus of scientists is that carbon emissions must be drastically reduced to stop the growing climate crisis.

Once again, indigenous people and big business, and the planet and the government are facing off. That should be food for thought for Americans driving in their gas-guzzlers.

29 Oct 21 | About Index, Australia, News and features, The climate crisis, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

The bushfires that tore across Australia in the summer of 2019-20 left in their wake 18 million hectares of scorched land. A total of 33 people – including nine firefighters – lost their lives, and close to 3,500 homes were razed to the ground. Ecologists calculated that as many as one billion animals perished in the fires, while economists estimated the cost of recovery at an unprecedented AU$100 billion.

Faced with tallies of destruction too big to comprehend, Australians cast about for clarity on why this disaster was unfolding, and how it could be prevented from happening again the future. Conveniently, there was a living culture with 65,000 years of experience in caring for the country to turn to for answers.

The fires precipitated a sudden torrent of interest in traditional Aboriginal land management techniques. First Nations rangers, practitioners and traditional knowledge experts – so rarely afforded time on the airwaves – were widely consulted on national television and radio shows. For many Australians, it was their first time hearing about “cool burning” and “fire-stick farming”: traditional methods of burning patches of bushland at low temperatures to clear the undergrowth without damaging root systems and curtail the risk of out-of-control bushfires in the arid heights of summer.

Yet these practices are ancient. They’ve been passed down through generations of Aboriginal Australians, forming part of the symbiotic relationship that First Nations people have with the environment as custodians of the land.

“Think of it like this: an Aboriginal man 300 years ago didn’t have to worry about handing a climate emergency on to the next generation,” said indigenous cultural educator and Wiradjuri man Darren Charlwood.

“What they were handing on to their children was an understanding of how to survive, how to respect their country, how to respect their ancestors in doing so, and how to practise all this through land management, through ritual, through their interactions within their social organisation and systems.”

While the unprecedented interest in traditional knowledge from the media, the government and conservation organisations was undeniably welcome, for educators such as Charlwood – who works for Sydney’s Royal Botanical Gardens and the New South Wales government’s National Parks and Wildlife Service – it was also frustrating.

“If that sort of engagement had come into play a lot earlier, we probably wouldn’t have had as big a catastrophe as we did,” he said. “Traditional fire management is wonderful, and it can really help with the plight of our environment in Australia. But, mind you, this was a climate catastrophe. Traditional land management would have saved only so much. The bottom line is the climate is changing.”

The consultation-after-the-fact that occurred in the wake of the 2019-20 bushfires is symptomatic of a more troubling “selective listening” that Australia’s First Nations people encounter across the political spectrum – from the prime minister’s office to the halls of local government – especially on land and environment issues.

It’s something that Yvonne Weldon, Australia’s first Aboriginal candidate for Lord Mayor of Sydney, is looking to change.

For Weldon, the principle of inclusion is at the core of an indigenous approach to leadership and environmentalism. It’s a value she places at the heart of her campaign.

“Inclusion is who we are as First Nations people,” she said. “Our ability to be inclusive – to hear what others are saying and act with sensitivity to their existence – is how we have been able to survive.”

She added that the same logic applied to the environment. “Prior to Invasion we didn’t have polluted parts of our country. We didn’t take any more than was needed. Whatever ecosystem you were a part of, you had to live in harmony with it. You didn’t do it at the expense of other living things.”

Reaching for the top

Weldon and her team at Unite for Sydney launched their campaign at Redfern Oval in May, nearly 20 years after then-prime minister Paul Keating’s historic Redfern Speech, where he recognised the impact of dispossession and oppression on First Nations peoples, and called for their place in the modern Australian nation to be cemented.

“It’s about creating moments that represent a landmark for inclusion,” explained Weldon. “And, hopefully, those moments happen closer and closer together in time until inclusion is no longer the exception, it’s commonplace.”

Weldon is a proud Wiradjuri woman who grew up in the inner-city suburb of Redfern, Sydney. With 30 years of experience as a community organiser and campaigner, she has spent her adult life advocating for the disadvantaged. She is a board member of Domestic Violence NSW and Redfern Jarjum College – a primary school supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children needing additional learning support – as well as deputy chair of the NSW Australia Day Council. She’s also the first Aboriginal person to run for the top job at the City of Sydney Council.

“To me, the fact that I’m the first Aboriginal person to run for Lord Mayor of Sydney in 2021 is insulting,” she said. “It’s an insult because it hasn’t been done before in this country, and yet we think we have progressed.”

Running on a platform of effective climate action, genuinely affordable housing and better community engagement, the campaigner-turned-candidate sees plenty of opportunities for improvement.

“True leadership has to be inclusive of all, and what I’ve seen in local government has fallen way short of that.”

She realised she had to take a run at the job after six years as elected chair of Sydney’s Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council (LALC) – an organisation set up by law to advocate for the interests of local Aboriginal people in relation to land acquisition, use and management.

In her experience, representatives of the City of Sydney Council have chosen to engage only when it suits their purposes, and either reject proposals for meaningful change out of hand or use inordinate process as a way of keeping them in check.

It’s an all-too-familiar story in Australia, where the government has been unwilling to reach a treaty with its indigenous people comparable to those of New Zealand, Canada or the USA.

Aboriginal calls for recognition were formalised in 2017 with the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which called for a First Nations Voice enshrined in the constitution, and a treaty to supervise agreement-making and truth-telling with governments.

But the historical consensus was rejected outright by then-prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and denigrated by the deputy prime minister, Barnaby Joyce, who called it an “overreach”.

Following a 2018 parliamentary inquiry which found the Statement from the Heart should indeed be enacted, the current Australian government has delayed plans to introduce relevant legislation until after the next federal election in 2022.

A long fight

The application of “selective listening” to First Nations calls for autonomy over their own land is, historically speaking, one of the foundations that modern Australia was built on.

“The damage that’s been done to Australia over 250 years of not respecting indigenous people or knowledge… you can really see it in our environment, it’s very much on show,” said Charlwood. “Because of the way that people have introduced invasive animals and plants to Australia, because of practices like mining and the way people engage with the landscape here, Australia has lost more wildlife in a shorter time than anywhere else on Earth.”

According to Heather Goodall – professor emerita of history at the University of Technology in Sydney – there is historical evidence that Aboriginal people in New South Wales made efforts to secure broad tracts of land where they could feel a sense of safety and belonging, access sites of cultural significance and act as custodians for the environment as early as the 1840s, when the first “reserves” were established.

Despite a movement which involved direct action, writing their own petitions and recruiting sympathetic white men to convey their demands to authorities, Aboriginal people were gradually moved to government-delineated reserves, missions or small parcels of land for agricultural use.

“Consultation is often about seeking opinions which will be used to justify a decision that has already been made. It’s a very hard-to-define term that often doesn’t mean having decision-making power,” said Goodall.

That’s a sentiment Weldon can relate to. “Aboriginal people are not one people – there are hundreds of different nations and tribes and clans all across the country,” she said.

“Bearing in mind the diversity of Aboriginal Australia, often what people in power do is if they don’t want to hear what one group has to say, they’ll go to another group until they find someone to say what they want to hear. I call it ‘shopping around’.

“They’ll play people off each other, they’ll offer little crumbs, they’ll do all these types of things because that’s the colonial viewpoint. It’s about creating the notion that you’re open and inclusive, when actually you’re orchestrating it all for self.

“Sydney represents ground zero, where the impact of colonisation began,” she added. “But you can’t talk about reviving or respecting traditional knowledge if you’re not inclusive of First Nations people.”

As another generation of Aboriginal Australians stands ready to share knowledge and lead the way to a more sustainable future, the question remains whether other Australians are ready to listen – and ready to vote.

27 Oct 21 | News and features, The climate crisis, Turkey, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

“Funded by George Soros and the Rockefeller family, Greenpeace organises chaotic events around the world, spearheading protest movements against the construction of the Istanbul Canal,” Yeni Akit, the Turkish government’s favourite far-right newspaper, reported recently.

The artificial sea-level waterway, if it gets built, will connect Marmara with the Black Sea, with an outcome most experts agree will be catastrophic for Istanbul and the Marmara Sea. But Turkey’s Islamist government brands anyone opposing its ecocidal project as traitors and foreign agents.

“Greenpeace issued a statement, ‘No to the Istanbul Canal’, on its website, insistently disseminating the lie that this project will harm the environment,” the pro-government daily warned, calling the canal “the project of the century” and describing criticisms and warnings from activists, experts and scientists as “mere propaganda”.

Attacks on environmental activists have never been greater in Turkey, where laws passed under the state of emergency in 2016 continue to allow Islamists to detain dissidents and NGO workers as “terrorist sympathisers”.

For Özgür Gürbüz, one of Turkey’s most seasoned environmental activists, the atmosphere of 2021 is reminiscent of the early 2000s.

Since the 1990s, Gürbüz has organised petitions against the construction of nuclear plants in Turkey; marched outside embassies to protest against nuclear projects by Chinese, French, Japanese and Russian companies; and once walked, backwards, from Mersin to Akkuyu – a 170km journey – to make his voice heard.

One of Turkey’s first environmental reporters, Gürbüz worked for the liberal Yeni Yüzyıl newspaper in 1996 when he began covering protests against Turkey’s first gold mine in the Anatolian town of Bergama. The Canadian company that operated the mine used cyanide in the extraction process. Villagers who opposed the technique placed ballot boxes in Bergama’s town square and held a vote, using direct democracy to settle the issue. They also travelled to Istanbul and, wearing Asterix and Obelix costumes, walked on the city’s Bosphorus Bridge carrying banners that read: “Hey police, first listen to what we have to say, then you can beat us!”

Gürbüz frequently travelled from Istanbul to Bergama to cover the protests. “Then one day,” he recalled, “a massive conspiracy theory, designed to demonise Bergama’s villagers, emerged.”

A German plot

According to the ultra-nationalist press, tales about cyanide were but a plot devised by a network of German NGOs, spearheaded by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, to bring Turkey to its knees. Ankara’s State Security Court opened a case in 2002, where 15 NGO workers faced spying charges which carried prison sentences of up to 15 years.

Meanwhile, a Turkish mining company called Koza had taken control of Bergama’s mine. Gürbüz smelt a rat. Whenever he called Koza, the company’s press officer asked him: “Do you know what German NGOs had been doing here? Let me send you a cache of information!” But a brief glimpse at the documents showed they contained nothing “but unfounded claims”.

Gürbüz believes Koza had disseminated disinformation to dissuade patriotic Turks who supported the uprising from opposing their takeover. It later transpired that Koza was one of the companies operated by the movement of Fetullah Gülen, the Islamist preacher who allied with president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in the 2000s to purge secularists from Turkey’s public sector.

This tactic of criminalising civil society cast a long shadow that continues to this day.

“Sometimes they accuse us of being German spies; other times we’re British collaborators. Countries change; the accusation of being in the pay of foreign powers does not,” Gürbüz said. “But their accusations devastated Bergama villagers. I know them. They love their soil, and all they wanted was to practice agriculture.

“They are patriots, typical Anatolian people who suddenly found themselves on the telly, portrayed as German and British agents. It was impossible for them not to panic.”

For scholars and experts who worked for environmental causes, the prospect of a knock on the door from the security services became a real possibility. “The public broadcaster TRT gave airtime to the disinformation campaign featuring German NGOs. Such speculation exhausted and harmed Turkey’s burgeoning environmental movement,” said Gürbüz.

The spying case that began in 2002 came to nothing. Still, its mentality set the tone for the oppression of green activists over the next two decades, casting doubts on international NGOs just as the climate crisis worsened.

“Those who environmentalists rattle use whatever tool that comes in handy for them,” Gürbüz said, pointing to Aysin and Ali Ulvi Büyüknohutçu, a couple in their 60s known for their environmental activism in south-west Turkey, who were murdered in 2017. Gürbüz said: “They were trying to defend their environment. They received no funding, and yet the forces opposed to their struggle hired a young man to shoot them with a hunting rifle.”

Gürbüz sees a pattern in these cases where polluters use Turkey’s xenophobic climate to blame NGOs that oppose their ecocidal projects.

“Other tactics include tax controls, sending inspectors to NGOs to intimidate their workers,” he said.

To counter such manoeuvres, Gürbüz believes, journalists must act boldly. “In the past, we used to deal directly with the government because most polluters were public bodies. With the new autocratic regime, things are different. Private company CEOs are friends of newspaper tycoons who have ties to the government. Thanks to these intricate ties, the field for environmental journalism has shrunk.”

Tuna censorship

Gürbüz has suffered numerous instances of censorship. After identifying heavy metals in fish samples from the Marmara Sea, his newspaper refused to print the word “tuna” to avoid angering advertisers. (He published the uncensored version on his blog.) When he travelled to Yatağan to report on the public health implications of a thermic plant, his editor refused to publish the report, fearing that the company behind the project might become the newspaper’s new owner.

“This is why independent media is so crucial for the environmental struggle,” Gürbüz said.

After his reporting career came to an end, he spent a year in China before, on returning to Turkey, entering the NGO world, working for Greenpeace Mediterranean’s energy campaign and moving to the Heinrich Böll Foundation to become project co-ordinator, overseeing which projects to fund. He also worked for WWF Turkey.

Then, in 2013, everything changed with Occupy Gezi, the biggest environmentalist protest in Turkey’s history.

“Thousands of people marched there, and they managed to save the park,” he said. “Honestly, it isn’t easy to see how such events begin and shapeshift. A handful of my friends who were collecting signatures outside Gezi suddenly saw their supporters snowball into thousands after bulldozers entered the park and cops burned their tents.”

As Gezi grew, Turkey’s Islamists once again branded environmental activists as foreign agents funded by “the interest lobby”, a dog-whistle term used to appeal to their antisemitic voters. Pro-government papers identified the German airline company Lufthansa’s jealousy of Istanbul’s planned new airport as the reason behind “the German hand” in protests.

But Gürbüz said: “If you want the agents behind Gezi, why don’t you look at the people who advised the government to build a shopping mall there in the first place? If it weren’t for them, these protests would never have happened.”

And yet their rabid discourse is still with us. Dozens of scientists, environmentalists and scholars have written extensively about the Istanbul Canal’s disastrous effects, and “it would be a strategic mistake for the government to try to present this as another foreign-funded opposition campaign”, Gürbüz said – but that is precisely what is happening. “This discourse is an insult to the mind of this nation.”

Turkey’s Green Party

In 2008, Gürbüz served as a co-founder of Yeşiller (Green Party), the second iteration of a party that originally launched in 1988. The original Yeşiller emerged as a fresh voice in the leftist circles that the 12 September coup in 1980 destroyed.

Koray Doğan Urbarlı, a green activist, has childhood memories of Yeşiller’s early protests. He said: “In 1990, when I was five, Yeşiller held a meeting in Izmir to oppose the construction of the Aliağa Thermal Power Plant. My parents also brought me to the Yatağan protests. I later learned that those were all Yeşiller events.”

In August 2008, Urbarlı attended a meeting organised by Yeşiller. The party was a month old, and it changed his life. Helping found its local Izmir branches, he devoted his life to Yeşiller.

There he also met Emine Özkan. Born in 1993, Özkan had spent her youth in an ultra-conservative family in Eskişehir, specialising in bird migration before starting work for NGOs. Today, Urbarlı and Özkan are spokespeople for Yeşiller’s third iteration.

“There was a straight line between bird preservation and politics,” Özkan said. “I discovered how LGBT rights, children’s rights and disability activism are all connected. Yet, as individuals, there is a limit to what we can achieve. The more we can organise this into a political struggle, the more we can deliver change.”

When she first entered the green struggle, just a few activists in Turkey were aware of the impending climate crisis. “Now, it impacts our lives daily. It adds to other problems: Turkey’s autocratic regime and economic crisis. What we have known and said in the background for years is now coming to the fore,” she said, adding that as authoritarianism increases and trust in the government diminishes, environmental NGOs and the women’s movement are on the rise.

“These days, oppressed people channel all their political frustrations via the green movement,” said Urbarlı, who accepts that talking critically about ecological issues is easier than in other fields in Turkey, such as those of minority or LGBT rights.

“In the past, we were seen as marginal figures; now what we say plays a crucial part in political debates.”

It’s little wonder Yeşiller is receiving the government’s cold shoulder. Despite submitting all the required documents on 21 September 2020, it has received no word from the Interior Ministry, which refuses to acknowledge it as a political party. “They neither deny nor affirm us. This violates our civil rights,” the co-founders said.

Turkey’s constitution clarifies that no one has the power to prevent a party’s foundation, and yet the government has “placed Yeşiller in limbo”.

Despite state muzzling, Yeşiller is hopeful for the future. “Looking at Occupy Gezi eight years on, we can see that the principles we held dear during the foundation of Yeşiller in 2008 were realised in the form of peaceful resistance, with demands for local democracy and gender equality,” Urbarlı said. “Gezi helped disseminate green ideas to bigger crowds, and it enlightens our ideas to this day.”

But the government’s xenophobic discourse has proved to be similarly resistant. When wildfires broke out in the country’s forests in late July, a social media campaign targeted Yeşiller after the party’s Twitter account pointed to climate change as the cause of the fires.

Pro-government newspapers said “Kurdish terrorists” were behind the fires; one journalist blamed the planting of “traitorous” pine trees as part of the Marshall Plan in the 1950s, calling it a sinister plan devised by “US imperialism” to burn Turkey to the ground with help from its “traitorous” local collaborators. The post was shared and liked by thousands.

“These conspiracy theories make people feel safe,” Özkan said. “This is the difficulty of environmental politics today. Despite these lynching attempts, we have to continue telling the truth.”

Urbarlı envisages a future in which the party can serve in a coalition government, anticipated to be formed after the general elections that are scheduled for 2023.

“It’s easy to be an environmentalist when you’re in the opposition,” he said, highlighting the example of Erdoğan, the Istanbul Canal’s architect, who used to conduct press conferences with Yeşiller to defend freedom of expression decades ago when he was the Istanbul head of the Islamist Welfare Party.

“Such is the difference between being in opposition and power, and it is a lesson we should learn from.”

25 Oct 21 | News and features, The climate crisis, Uganda, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

Uganda’s natural resources base, one of the richest and most diverse in Africa, continues to be degraded, jeopardising both individual livelihoods and the country’s economic development.

Evidence from the UN Environment Programme reveals that its forests, home to several endangered or soon-to-be extinct animal and plant species, are being mercilessly ravaged by poachers, illegal charcoal traders and loggers, and greedy investors.

Overfishing in the country’s lakes and rivers is rife. Its wetlands are being cleared for agricultural use and the rate of forest cover loss stands at 2.6 per cent annually, according to independent sources.

As part of efforts to ensure that the east African nation’s natural resources are effectively managed and protected, a group of environmental activists has gone to war to protect these natural wonders from bleeding further.

“Environmental activism in Uganda is not a safe identity – it’s a hostile and fragile environment,” William Amanzuru, team leader at Friends of Zoka, told Index.

“Activists are seen as fronting foreign views and opinions, enemies of the state and enemies of development.”

Amanzuru, who won the EU Human Rights Defenders Award in 2019, says environmental abuse in Uganda is highly militarised, so any intervention for nature conservation seems like a battlefield in a highly sophisticated war.

William Amanzuru, team leader at Friends of Zoka

“You directly deal with our finest military elite who run the show because of the huge profits gained from it,” he said. “We are always being followed by state and non-state actors and those involved in the depletion of natural resources like the Zoka Central Forest Reserve.”

Amanzuru said he had received threatening phone calls and had been intimidated by government and local police officials. “My phone is always tapped,” he added.

Anthony Masake, programme officer at Chapter Four Uganda, a human rights organisation, said environmental human rights defenders in Uganda were increasingly operating in a hostile environment.

“They repeatedly face reprisal attacks in the form of arbitrary arrests and detention, character assassination, being labelled traitors, assaults, intimidation and isolation, among others,” he said.

Masake added that illegal loggers and charcoal dealers, land grabbers and corporations often connived with their government backers to shield them from the law and accountability.

“Politicians, police officers and local leaders have often been cited in incidents of reprisal attacks against environmental defenders in Adjumani, Hoima and other districts,” he said.

Hidden from view

Uganda’s environmental battlefields are located in rural and remote areas where life and time seem to stop – far from the public eye and the noise and the vibe of big cities.

“The terrain has exposed them to easy targeting because the operation areas are far removed from urban areas where they would be able to access quick and competent legal services,” said Masake.

“The rise of incidents of corruption, abuse of office, lack of accountability for abusers and deterioration of the state and rule of law has further emboldened perpetrators to continue attacking environmental defenders because they know they can get away with it.”

As watchdogs of society, journalists who attempt to expose environmental crimes and abuse are also often the victims of sheer brutality and violence, according to several sources who spoke to Index.

“I deplore the way [president Yoweri] Museveni’s security forces ill-treat journalists, especially environmental journalists,” said one. “They have done nothing wrong. All they do is to tell the nation and the world that our natural resources are in danger of being extinct if we do not trade carefully. Is that a crime?”

The journalist, who claimed to fear Ugandan security forces and intelligence services “more than God”, spoke only on condition of anonymity.

Silencing the critics

The International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and its partners, the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and the World Organisation Against Torture, have vehemently and repeatedly condemned the arrest and arbitrary detention of environmental journalists.

Venex Watebawa and Joshua Mutale, the team leader and head of programmes at Water and Environment Media Network (Wemnet), were recently arrested in Hoima, in western Uganda, on their way to attend a radio talkshow at Spice FM.

The FIDH reported that they were supposed to discuss the risks and dangers of sugarcane growing projects in the Bugoma forest and of allowing oil activities in critical biodiversity areas including rivers, lakes, national parks, forests and wetlands.

Home to more than 600 chimpanzees and endangered bird species, including African grey parrots, Bugoma is a tropical rainforest which was declared as a nature reserve in 1932.

Following the arrest of Wemnet members, all hell broke loose when security forces arrested more environmental activists who went to the police station to negotiate the release of Watebawa and Mutale.

The arrests, which are believed to have been called for by Hoima Sugar, the company decimating the Bugoma forest to convert it into a sugarcane plantation, were a bitter pill to swallow. (Index asked Hoima Sugar to comment on these allegations but received no response.)

“Environment stories are so delicate because the people behind the destruction of the environment are people with a lot of money, who are well connected and have a lot of influence,” Watebawa told Index.

He slammed the National Environment Management Authority – which is mandated to oversee conservation efforts – for having been influenced by Hoima Sugar.

“To our surprise, it gave a report in a record time of two weeks to clear the below-bare-minimum-standard environmental impact assessment report to clear 22 square miles of land in a sensitive and fragile ecosystem,” he said.

“The deployment of paramilitary agencies to give sanctuary to the destroyers of the forest speaks volumes of the government’s commitment to protect the environment.”

Journalists who have attempted to get anywhere near the Bugoma central forests have been harassed or faced the wrath of the army.

“These incidents have demotivated and scared us,” said Watebawa. “Between March and June, two of our members lost their cameras and laptops. Our communications officer, Samuel Kayiwa, was trailed, his car broken into in Kajjasi, and his gear stolen.”

The trade in environmental abuse

In another incident targeting the environmental media, Wemnet reported that someone broke into the house of Agnes Nantambi, a journalist working for New Vision, after midnight, forcing her to surrender her laptop and camera.

Amanzuru was arrested in February after an incident in which locals impounded a Kampala-bound truck ferrying illegal charcoal. He claimed that the military provided protection for those investing in illegal logging, illegal timber harvesting and the commercial charcoal trade.

He said the country’s environment sector was highly politicised, with the government drawing a lot of illicit money from the abuse of natural resources.

“Politicians trade in environmental abuse because this is an unmonitored trade … They make quick money for their political sustainability.”

And as the Museveni government’s aggression towards environmental activists increases day by day, human rights organisations have vowed to fight and to die with their boots on.

Amanzuru’s arrest attracted the attention of the EU ambassador to Uganda, who wrote to environment minister Beatrice Anywar Atim to request a fair and speedy trial.

Entities offering support include the Defenders’ Protection Initiative, Chapter Four Uganda and the National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders in Uganda.

But despite the grim outlook, Watebawa remains optimistic about the future of environmental activism.

He says society is stronger, more organised and more determined than ever, and the media persistently exposes environmental abuse.

He believes all responsible citizens must challenge the impunity to which environmental human rights defenders so often fall victim because the environment, ultimately, is a shared resource.

22 Oct 21 | Afghanistan, News and features, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

Documenting the lives of women in Afghanistan, Forty Names by Afghan poet Parwana Fayyaz is a poignant reminder of lost opportunities, of freedoms given and then taken away, of a new generation living without enlightenment through education.

The collection, the title verse of which won the 2019 Forward Prize for Best Single Poem “focusses on stories and experiences from my childhood” and the ingrained attitude of acceptance that comes with a lack of schooling.

The title itself is reference to one of those very stories, where 40 women throw themselves off a cliff in order to protect their honour, rather than die with dishonour.

As she told Carcanet Press: “I grew up among women who told stories, stories concerning women. As the time passed, the women themselves became the stories. The majority of these women never went to school. They share their philosophy of life down through generations. [They say] “in the face of hardship, be patient, patience is the remedy”.”

Born in 1990, Fayyaz’s education challenges this idea. Now with a PhD in Persian Studies from Cambridge University, how can silence possibly make sense?

“When I left my home and Afghanistan to embark on my journey to become more educated, I began to reflect on the lives of the women I had always admired,” she said. “I began to question my admiration for them. They were suffering and yet they accepted it. To suffer in silence is seen as a token of patience.”

“With more education, patience became more elusive.”

Indeed, the choice now for so many women and girls in Afghanistan, sadly, is only silence and patience, but without the reward the piety is supposed to bring. As the Taliban tightens its stranglehold over the country, it forces out the oxygen required for art and literature to flourish and for women to learn how to express themselves in this sense.

Certainly, more than they previously should have done, everyday people in the west are taking notice of Afghanistan. The stories and images that have shocked so many people are not new, but it quite obviously takes a feeling of personal involvement – Nato troops were caught in a dangerous evacuation process – for people to take notice for long.

Even the process of translation for Fayyaz was important in this regard, “My poetry makes use of the art of translation to enhance the meaning of my story-poems for a Western audience, specifically involving the translation of Persian names into English. In active translation, the Persian names are the sounds and the English translations their echoes.”

Perhaps, to the English-speaking world, the plight of Afghans under the Taliban will remain as far-distant noises that will not reverberate so loudly for long. Forty Names, then, is in its truest sense a reflection of what has been lost for a whole generation of Afghan girls: a reminder that Afghanistan’s brief experience of democracy will never be forgotten.

Forty Names

by Parwana Fayyaz

I

Zib was young.

Her youth was all she cared for.

These mountains were her cots

the wind her wings, and those pebbles were her friends.

Their clay hut, a hut for all the eight women,

and her Father, a shepherd.

He knew every cave and all possible ponds.

He took her to herd with him,

as the youngest daughter

Zib marched with her father.

She learnt the ways to the caves and the ponds.

Young women gathered there for water, the young

girls with the bright dresses, their green

eyes were the muses.

Behind those mountains

she dug a deep hole,

storing a pile of pebbles.

II

The daffodils

never grew here before,

but what is this yellow sea up high on the hills?

A line of some blue wildflowers.

In a lane toward the pile of tumbleweeds

all the houses for the cicadas,

all your neighbors.

And the eagle roars in the distance,

have you met them yet?

The sky above, through the opaque skin of

your dust, carries whims from the mountains,

it brings me a story.

The story of forty young bodies.

III

A knock,

father opened the door.

There stood the fathers,

the mothers’ faces startled.

All the daughters standing behind them.

In the pit of dark night,

their yellow and turquoise colors

lining the sky.

‘Zibon, my daughter,

take them to the cave.’

She was handed a lantern;

she took the way.

Behind her a herd of colors flowing.

The night was slow,

the sound of their footsteps a solo music of a mystic.

Names:

Sediqa, Hakima, Roqia,

Firoza, Lilia, Soghra.

Shah Bakhat, Shah Dokht, Zamaroot,

Naznin, Gul Badan, Fatima, Fariba.

Sharifa, Marifa, Zinab, Fakhria, Shahparak, MahGol,

Latifa, Shukria, Khadija, Taj Begum, Kubra, Yaqoot,

Nadia, Zahra, Shima, Khadija, Farkhunda, Halima, Mahrokh, Nigina,

Maryam, Zarin, Zara, Zari, Zamin,

Zarina,

at last Zibon.

IV

No news. Neither drums nor flutes of

shepherds reached them, they

remained in the cave. Were

people gone?

Once in every night, an exhausting

tear dropped – heard from someone’s mouth,

a whim. A total silence again.

Zib calmed them.

Each daughter

crawled under her veil,

slowly the last throbs from the mill-house

also died.

No throbbing. No pond. No nights.

Silence became an exhausting noise.

V

Zib led the daughters to the mountains.

The view of the thrashing horses, the brown uniforms

all puzzled them. Imagined

the men snatching their skirts, they feared.

We will all meet in paradise,

with our honored faces

angels will greet us.

A wave of colors dived behind the mountains,

freedom was sought in their veils, their colors

flew with wind. Their bodies freed and slowly hit

the mountains. One by one, they rested. Women

figures covered the other side of the mountains.

Hairs tugged. Heads stilled. Their arms curved

beside their twisted legs.

These mountains became their cots.

The wind their wings, and those pebbles their friends.

Their rocky cave, a cave for all the forty women.

And their fathers and mothers disappeared.

Three Dolls

During the wars,

my mother made our clothes

and our toys.

For her three daughters,

she made dresses, and once

she made us each a doll.

Their figures were made with sticks

gathered from our neighbor’s garden.

She rolled white cotton fabric

around the stick frames

to create a skin for each doll.

Then she fattened the skin

with cotton extracted from an old pillow.

With black and red yarns bought from

uncle Farid’s store, my mother created faces.

A unique face for each doll.

Large black eyes, thick eyelashes and eyebrows.

Long black hair, a smudge of black for each nose.

And lips in red.

Our dolls came alive,

with each stitch of my mother’s sewing needle.

We dyed their cheeks with red rose-petals,

and fashioned skirts from bits of fabric,

from my mother’s sewing basket.

And finally, we named our dolls.

Mine with a skirt of royal green was the oldest and tallest,

and I called her Duur. Pearl.

Shabnam chose a skirt of bright yellow

and called her doll, Pari. Angel.

And our youngest sister, Gohar, chose deep blue fabric,

and named her doll, Raang. Color.

They lived longer than our childhoods.

Her Name is Flower Sap

Somewhere – in the no-man’s land,

there are high mountains, and there is a woman.

The mountains are seemingly unreachable.

The woman in her anonymity is untraceable.

The mountains are called the Tora Bora.

The woman is known as Sharbet Gula, Flower Sap.

In her faded-ruby-red Chador, she appeared

a young girl with a frown, with her green eyes.

Not knowing where to look.

When the world looked back at her.

As young kids, refugees of wartime in Pakistan

we were equally intrigued with her photograph.

‘Her eyes have the magic of good and bad.’

‘The light of her eyes can destroy fighter jets.’

So went Afghan children’s conversation

in the aftermath of 9/11. ‘But could she take down

The Taliban jets,’ we wondered,

as the jets crossed the skies in one song.

But Flower Sap could never answer us.

For she had disappeared like our childhood.

*

As the borders became damper lands,

Afghans like soft worms crawled toward their homeland.

In the in-between mountains,

Flower Sap re-appeared, without any answers.

Now she was a grown-up woman.

A mother of four girls. A widow.

There were some questions in her eyes.

The ones I had seen in my parents’ eyes.

Where do we go next? Now that our country is free.

She still did not have any answers.

And where was the power of her eyes?

I then saw her smiling. As an immigrant, I smiled too.

For her name saved the day.

She was taken to a hospital for her eyes.

The president of the county met her,

and sent her on a pilgrimage.

Her name educated her daughters,

it gave her a house and a reason to return to her homeland.

What else is there in the names and naming?

If not for reparation.

Forty Names was published in July 2021 by Carcanet Press, carcanet.co.uk

22 Oct 21 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] On 15 October 1971, in the depths of the Cold War, the feted British poet Stephen Spender wrote an impassioned appeal for the Times Literary Supplement in which he highlighted the threat of a world without creativity or impartial news as repressive regimes sought to silence dissent.

On 15 October 1971, in the depths of the Cold War, the feted British poet Stephen Spender wrote an impassioned appeal for the Times Literary Supplement in which he highlighted the threat of a world without creativity or impartial news as repressive regimes sought to silence dissent.

Writers, academics, journalists and artists were subject to state sanctioned persecution on a daily basis, threatened, arrested and in too many cases murdered as authoritarian leaders moved against their citizens. Watching was no longer enough, letters to the Times and statements of solidarity were no longer sufficient for Spender and a group of his contemporaries.

It was time to act, to provide an international platform for dissidents to publish their work and importantly it was time to make a positive argument for the liberal democratic values of free speech and free expression. It was time to launch Writers and Scholars International and its in-house journal Index on Censorship.

Spender concluded: “The problem of censorship is part of larger ones about the use and abuse of freedom.”

In the 50 years since Spender wrote in the TLS, Index has published the works of thousands of dissidents, their words, their art and their journalistic endeavours. From Havel to Rushdie, from Zaghari-Radcliffe to Ma Jian, their works have found a home in our publication. Their stories have been told and their works published for posterity – a recognition of their plight.

Fifty years later Spender would have hoped for us to be irrelevant, that the fundamental freedom of free expression was not just respected but embraced throughout the world. If only that was the case. Every week there is an attack on academic freedom at home or abroad, a new debate about our online rights and a new report of a systematic attack on those that embody the very principle of free speech.

In 1971 over a third of the world’s population lived under Communist rule with still more living under other forms of totalitarian regime. Today 113 countries, representing 75 per cent of the global population, completely or significantly restrict core human rights.

These aren’t just statistics, there are real people behind each headline.

In Belarus 811 people are currently detained as political prisoners by Lukashenka, including Andrei Aliaksandrau one of Index’s former staff members. In Egypt more than 60,000 people are imprisoned, including our award-winner Abdelrahman Tarek – detained and regularly tortured since the age of 16 for attending democracy demonstrations. In Afghanistan three young female journalists were brutally assassinated as they left work earlier this year. In Hong Kong the 50 leading democracy protestors have been arrested by the CCP and their families threatened.

These brave journalists and campaigners represent millions of people who cannot use their voices without fear of retribution. Every day they face a horrendous choice between demanding democratic rights or being silenced.

Index seeks to be a platform for them – providing a voice for the persecuted, ensuring that no tyrant succeeds in silencing dissent.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also wish to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Oct 21 | Opinion, Ruth's blog, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Sir David Amess, MP for Southend West in Essex. Photo: John Stillwell/PA Archive/PA Images

On Monday afternoon British politicians united in memory of a fallen colleague. In shock, those that knew him best spoke one after another of the good man that they knew – Sir David Amess. After a weekend of tears and horror, as once again we tried to come to terms with another brutal attack on our democracy, it was the stories of the man who embodied British democracy – who dedicated his life to his constituents and who as one of the longest-standing parliamentarians in the UK had offered a smile and a word of support and friendship to every new member as they joined him in Westminster – which provided comfort to his friends and colleagues.

I was one of those who benefitted from that smile and support and it’s his smile that I will strive to remember in the months and years ahead, but it’s also a smile I have struggled to emulate in the hours since I learned of his brutal murder on Friday.

Sir David’s murder was an act of terrorism. It was an attack on every democratic value that we hold dear. It was devastating. It also wasn’t the unique – to either the UK or democracies around the world. Ideologues and extremists have throughout history targeted our elected representatives as the ultimate attack on our democracy. Assassination is the ultimate attempt to silence opposition, to incite fear and to undermine the very values that we live by. By its very nature it is also an attack on our collective free speech. And this was an attack that personally shook me to my core – again.

Friday brought back every horrendous memory of Friday 16 June 2016, the day that my colleague and friend, Jo Cox, was assassinated by a far-right extremist. On that Friday I was in a meeting when a member of my team asked me to follow them into the hall to tell me Jo had been attacked. My mum arrived at my office is tears and in the days that followed I and my former colleagues, in the middle of our grief, had to decide how, and if, we could still do the jobs as elected representatives.

We collectively decided to keep going, to take precautions but fundamentally to make sure that our democracy held strong. That isn’t to say that that decision came without cost. Our families worried every day about our security. Our political discourse got increasingly toxic and abuse and threats became even more prevalent. Within weeks of Jo’s murder I received thousands of pieces of abuse and death threats which meant I had to move home.

This level of abuse and intimidation of our elected representatives is unacceptable. Things have to change. Our democracy is precious and we need to cherish it, to defend it and most importantly to defend it. So for Jo, for Sir David and for everyone that bullies and extremists have tried to silence – we must say enough is enough. Things have to change. This is too important to leave to chance.

And to my former colleague, the man with the generous smile – Sir David, may you Rest in Peace. And may your memory be a blessing for everyone who knew you.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Oct 21 | Ecuador, The climate crisis, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117715″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Ecuador is not a safe country for environmental defenders. They are criminalised, threatened, attacked and even assassinated for attempting to uphold the rights of nature decreed in the constitution.

While the overt incitement to hatred against environmental activists ended when Lenin Moreno replaced Rafael Correa as president in 2017, and some imprisoned indigenous leaders were freed, the intimidation and threats continue.

In 2018, there were several attacks against members of the Collective of Amazonian Women who work to defend the Amazon region from oil and mining. Margoth Escobar had her house set on fire and Patricia Gualinga, from Sarayaku, had rocks thrown through her bedroom windows at night. Others received death threats.

The same year, three water defenders – including Yaku Pérez Guartambel, then president of indigenous peoples’ organisation Ecuarunari – were kidnapped by mine workers, believed to have been following orders from above. An angry mob kicked, dragged and tortured Pérez Guartambel, accusing him of leading anti-mining efforts. They planned on crucifying him and started gathering materials until a group of journalists broke through with cameras and rescued him.

Since a 2019 uprising of indigenous peoples in the country, the government has more forcefully set its sights on the indigenous movement as the internal enemy to be defeated.

Indigenous leaders are repeatedly persecuted and intimidated. The repressive apparatus has been strengthened, with millions of dollars allocated for the provision of equipment for the police and military. The creation of a new legal framework in May 2020 would have enabled the deployment of the military to control internal order. This would have provided protection to strategic sectors such as mining, against which indigenous communities have been struggling for years.

In May 2021, right-wing banker Guillermo Lasso assumed the presidency in Ecuador, ending more than a decade of left-wing rule. Index on Censorship spoke to Franco-Brazilian academic and indigenous rights activist Manuela Picq about what the change means for censorship. After marrying Yaku Pérez Guartambel in an indigenous ceremony, Picq was herself censored by the government of Rafael Correa, which forced her into a three-year exile.

“There are many ways of censoring. We have seen traditional censorship mostly from the left in Ecuador, by Correa in particular, who implemented very repressive media legislation and enforced it with violent oppression. Then there are other forms of censorship, which are not traditionally recognised as such, the neo-liberal way of buying support. Under Lasso, journalists and media outlets are not fulfilling their critical role because they receive so much state advertising revenue. I see this as a form of censorship, when the public is left uninformed about the government’s activities, which happen largely in the dark. In this context, whistle blowers will play a critical role,” said Picq.

“This is a weak government that has been forced to ally with Pachakutik, the political party of Ecuador’s indigenous movement, which is currently presiding over congress. This means Lasso will carry out his agenda in the most discreet way possible, to avoid being overthrown. So, mining in indigenous territories, or the privatisation of the public sector will be labelled as “development”. We are relieved in Ecuador that we no longer have Correa-ism, with its traditional, explicit forms of censorship, but we should not underestimate the other forms of censorship that are more subtle and insidious.”

The multicoloured people

Jimmy Piaguaje is a young indigenous Siekopai defender from Siekoya Remolino, a community of 53 families living on the banks of the Aguarico River in the north-eastern Ecuadorian Amazon region.

The Siekopai (which means multicoloured people) are renowned for their shamanic acumen and knowledge of medicinal plants, with uses for more than 1,000 different plants.

The Siekopai are known as the multicoloured people, photo: Erin Deo

In the 1600s, when Jesuit missionaries arrived in Siekopai territory, there were 30,000 to 40,000 Siekopai in the zone between Putumayo, the Aguarico River and Napo.