10 Aug 21 | Belarus, Index in the Press, Media Freedom, Uncategorized

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Journalist and former Index colleague Andrei Aliaksandrau

Few things can better describe the spirit of Liverpool fans better than the words etched in gold above the Shankly gates.

When Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein sat down to write the musical Carousel and its anthem, You’ll Never Walk Alone, they did not envisage it becoming a hymn for the masses, cascading down the creaking terrace of the Kop for decades after they penned its stirring lyrics.

It has provided hope in times of sorrow and ecstasy in times of glory at Anfield. Now it is giving comfort to a Belarusian journalist wrongly locked in a jail cell.

Journalist and Liverpool fan Andrei Aliaksandrau previously worked in the UK at the charity Index on Censorship – where I now work on placement from Liverpool John Moores University – for a number of years before returning to his native Belarus. The organisation, set up 50 years ago this year, aims to help those wrongly imprisoned and persecuted for daring to express their views or for telling the truth about what is happening in countries with oppressive regimes. Little did Andrei know; he would one day require our help.

Andrei was detained – along with his girlfriend Irina – in January this year and faces up to 15 years in prison in his home country due to a charge of high treason. His ‘crime’ was helping friends and colleagues pay off the oppressive fines given to them by the Belarusian authorities for their peaceful protests or covering demonstrations as journalists in the unrest following elections last August.

It is an act of generosity that Liverpool fans can recognise as the sort of community spirit and care for your fellow citizen that served them so well after the Hillsborough Disaster and through other projects such as Fans Supporting Foodbanks. Bill Shankly, who was known for welcoming many a supporter to his home, would surely have approved.

The situation in Belarus is dire. The president, Alexander Lukashenko (known often as “Europe’s last dictator”), has been in power since 1994, after the break-up of the Soviet Union of which the country was previously a part. Lukashenko declared himself winner of the 2020 elections with 80% of the vote. Opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya disputed the result and was forced to flee to Lithuania. Following the election, the UK and many other governments said they would not accept the outcome, yet Lukashenko acts with impunity because of ongoing support from Russian leader Vladimir Putin.

Outrage over the result erupted in countrywide protests, demanding Lukashenko step down. But these demonstrations were met with a mass crackdown. Journalists, activists, lawyers and other regular citizens have been arrested and detained by the thousands. Over 1,000 were arrested in a single day in November alone.

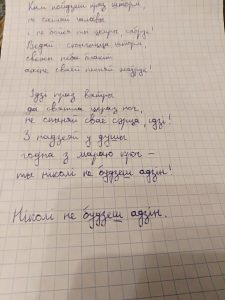

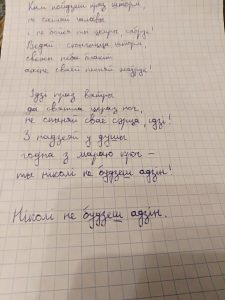

Andrei’s translation of the lyrics of Liverpool FC anthem You’ll Never Walk Alone

As of 6 July, the number of those arrested stands at more than 35,000. According to the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), 29 reporters, including Andrei, remain in captivity and 87 have been arrested since January 2021. They have been arrested because Lukashenko does not like what they are writing.

The conditions in Belarusian jails are appalling and a number of those detained have been tortured.

And yet, our former colleague Andrei has seemingly remained upbeat and has not cowed in the face of a regime that wants him silenced. Indeed, it seems that the famous words of Rodgers and Hammerstein have steeled another in times of adversity.

The connection, aside from the fact the song is indeed the club’s official anthem, is obvious. People in Liverpool have faced years of adversity and strife, be it through the bombing of the docks in the Second World War, the strikes of the 1970s and 1980s, or the dreadful injustice of the Hillsborough Disaster in 1989, their ability to draw resilience from a few lines of a musical written in 1945 has always been remarkable.

So, when a Liverpool fan watches, thousands of miles away, as his home country is torn apart by greed and corruption, it is little wonder that his own resolve derives from the very same words.

In a letter to Andrei Bastunets in April, chairperson of the BAJ, the jailed Aliaksandrau offered words of comfort to his close friend, quipping “It turned out so funny. As I went to jail, Liverpool stopped playing properly!”

Even though it was Aliaksandrau behind bars, it was Bastunets receiving reassurance. Aliaksandrau wrote: “In general, there were many reasons to repeat the club’s anthem to myself – You’ll Never Walk Alone.”

“Words of support from letters (sometimes – with the results of the matches) made me sing [and] play it in my head. One day it got to the point where I caught myself mumbling the club’s anthem in Belarusian. It seemed a bit pompous – but it is a hymn.”

“But it seemed to me that it was somehow in tune with the moment, [with my] feelings or mood. So, I decided to share it with you. As an Arsenal fan (sorry for this) you will understand me. At least [you know] what they sing about in Liverpool. And – you will never be alone!”

Andrei’s words remained upbeat despite the Belarusian regime making it even more difficult for Aliaksandrau since his arrest.

Those detained in the country must be released after six months unless they are charged and Andrei was expecting to be released around now, perhaps with a fine as others have been. But the authorities have now slapped the treason charges on him and he faces an uncertain future.

It was also announced in mid-July that Andrei’s lawyer Anton Gashinsky had his license revoked by the authorities. The prominent human rights lawyer also counts among his clients Sofia Sapega, the girlfriend of Roman Protasevich, the journalist who was recently arrested after his Ryanair flight was forcibly redirected by the Belarusian authorities when flying over Belarusian airspace after a faked bomb scare.

Dzmitry Navazhylau, Andrei’s friend and former colleague at Belapan news agency, where Aliaksandrau worked as deputy director, spoke of his friend’s sheer joy that could be found from watching his team.

“Liverpool FC, without exaggeration, is Andrei’s love,” said Navazhylau. “He is one of few Belarusians to have LFC Official Membership. He watched all Liverpool games on the internet with English commentary.”

Andrei used his time in the UK to good effect, he says.

“While working in London, he was lucky enough to see the Reds play live. At one point, there was no way to get a ticket to Anfield. Therefore, Andrei bought a season ticket for Fulham’s home games. He bought a season ticket for another club’s matches to attend one game of his favourite team! But it was worth it!”

Navazhylau recalls: “The most memorable match we watched together was the 2019 UEFA Champions League Final – Liverpool against Tottenham Hotspur. We were dressed in Liverpool kits, chanting, and singing “You’ll Never Walk Alone”. When Salah and Origi scored their goals, and especially after the final whistle, Andrei was as happy as a child.”

Andrei and his friend Dzmitry Navazhylau

It is unknown exactly when his fascination with the Reds began, but it is clear that his upbringing was in a household that was football mad. According to his friend and fellow journalist Kanstantin Lashkevich, Andrei’s father is “probably the only amateur statistician who tracks Belarusian lower-level leagues results”.

Like many fans, Andrei has spent a great deal of time, effort and money has been spent following his team over the years and it is a love for football and club that many on Merseyside can relate heavily to, as is his particular admiration for manager Jürgen Klopp and midfielder James Milner. He also travelled to Munich in 2019, as a journalist, to cover Liverpool’s quarter final Champions League tie with Bayern Munich.

And yet the reality is that, immortal as the words of You’ll Never Walk Alone are, they should not be used to sustain the sanity and goodwill of a man who has given much of his career to the protection of others.

Andrei’s situation is a reminder of how the day-to-day lives of people in a supposed democracy can deteriorate and why protests and free speech are so vital to protecting our individual rights and liberties.

When around 10,000 Liverpool fans marched out of a home game against Sunderland in 2016, protesting the rise of ticket prices, nobody was arrested.

When any person in the UK has to face the courts, for whatever reason, they do not have their legal representation forcibly removed from them.

But both of these things did happen to Andrei Aliaksandrau, whose only crime, many would argue, was embodying the spirit of what it is to be a Liverpool fan.

So how can Liverpool fans help Andrei realise he is not ‘walking alone’? You can sign the petition calling for the release of Andrei and his girlfriend – https://freeandreiandirina.org/ – and write to your local MP calling on the UK government to do more than just condemning the actions of ‘Europe’s last dictator’.

This article was originally printed in issue #276 of Liverpool FC fanzine Red All Over The Land. It has been published online with the kind permission of John Pearman. You can buy a copy outside Anfield on matchdays, or online here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”172″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

09 Aug 21 | Lukashenko letters

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row” css=”.vc_custom_1628261066056{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/lukashenko-letter-background-scaled.jpg?id=117196) !important;}”][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Maria Kalesnikava”][vc_custom_heading text=”Musician and political activist

Detained on 9 September 2020″ font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:left”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”117197″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][vc_column][vc_column_text]Reader’s Note: In September 2020, the prominent Belarusian opposition figure Maria Kolesnikova was abducted from Minsk and taken to the border where security forces tried to expel her from the country; she ripped up her passport in defiance. In the days that followed she was charged with incitement to undermine national security and placed in pre-trial detention.

The letter that follows was written by Maria Kalesnkikova to her father on 16 July 2021, the day the Supreme Court rejected her complaint regarding the extension of her detention until 1 August. Her father, Aliaksandr Kalesnikov, had gone to the hearing to support his daughter wearing a T-shirt with Maria’s image on it. He initially refused access to the hearing so he took off the T-shirt, turned it inside out, and put it back on. He was then allowed to enter.

Aliaksandr has repeatedly been refused the right to visit Maria in detention. According to Maria’s sister, Tatsiana Khomich – referred to as “Tania” in the letter, Alexander has been denied permission to see his daughter on every occasion (more than fifteen times) with no explanation. On 4 August, Maria went on trial facing up to 12 years in prison on charges of extremism. The trial was closed to the public, including family members. Maria’s family said it was a relief to see her healthy and cheerful at the trail, albeit on television screens.

Tatsiana said that although Maria is writing a lot, her letters have become increasingly infrequent. Suppression of letters from political prisoners in Belarus is commonplace, denying family members and loved ones the chance to hear vital news. This is done to put pressure on individuals and their families. The letter below is the last communication Maria’s family have received from her. One year since the fraudulent elections in Belarus, Maria’s sister agreed to publicly share this personal letter between Maria and her father.

Letter from Maria Kolesnikova to her father Aliaksandr Kalesnikov:

16 July 2021:

Hi my dearly beloved world’s best dad!

How are you doing in this trying time?

I’m constantly thinking of you, grandpa and all our nearest and dearest – sending my hello’s and lots of hugs to all!

The court hearing took place today so I already know how you had to ‘get changed’ – I bet everybody in the detention centre could hear me laugh! You really think fast on your feet. You see, now nobody can doubt that I’m my father’s daughter – and I’m so proud to be one!

I’m so glad that you are keeping your spirits high and are managing to get through these crazy days with a good sense of humour :)

Keep it up!

Today I received two! Letters from you and two from A.

You wrote that you’re in awe with Tania – I’m also writing this in every letter to her. What she’s doing for me and our whole team is unbelievable and incredible.

Please ask her, as do I, to make sure that she takes good care of herself and makes every effort to find time to rest.

And of course, the joke that your Berlingo [car] is crumbling and ageing faster than you are has also put a smile on my face. And so it should be, Dad, you’ve got no need to crumble!

I’m well, healthy and cheerful!

Sending you and everybody a big-big hug!

Your Masha

May goodness persevere!

Love and hugs[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

06 Aug 21 | Canada, Eritrea, Hong Kong, Netherlands, News and features, Philippines, Syria, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117182″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

The number of journalists killed while doing their work rose in 2020. It’s no wonder, then, that a team of internationally acclaimed lawyers are advising governments to introduce emergency visas for reporters who have to flee for their lives when work becomes too dangerous.

The High Level Panel of Legal Experts on Media Freedom, a group of lawyers led by Amal Clooney and former president of the UK Supreme Court Lord Neuberger, has called for these visas to be made available quickly. The panel advises a coalition of 47 countries on how to prevent the erosion of media freedom, and how to hold to account those who harm journalists.

At the launch of the panel’s report, Clooney said the current options open to journalists in danger were “almost without exception too lengthy to provide real protection”. She added: “I would describe the bottom line as too few countries offer ‘humanitarian’ visas that could apply to journalists in danger as a result of their work.”

The report that includes these recommendations was written by barrister Can Yeğinsu. It has been formally endorsed by the UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights special rapporteur for freedom of expression, and the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute.

As highlighted by the recent release of an International Federation of Journalists report showing 65 journalists and media workers were killed in 2020 – up 17 from 2019 – and 200 were jailed for their work, the issue is incredibly urgent.

Index has spoken to journalists who know what it is like to work in dangerous situations about why emergency visas are vital, and to the lawyer leading the charge to create them.

Syrian journalist Zaina Erhaim, who has worked for the BBC Arabic Service, has reported on her country’s civil war. She believes part of the problem for journalists forced to flee because of their work is that many immigration systems are not set up to be reactive to those kinds of situations, “because the procedures for visas and immigration is so strict, and so slow and bureaucratic”.

Erhaim, who grew up in Idlib in Syria’s north-west, went on to report from rebel-held areas during the civil war, and she also trained citizen journalists.

The journalist, who won an Index award in 2016, has been threatened with death and harassed online. She moved to Turkey for her own safety and has spoken about not feeling safe to report on Syria at times, even from overseas, because of the threats.

She believes that until emergency visas are available quickly to those in urgent need, things will not change. “Until someone is finally able to act, journalists will either be in hiding, scared, assassinated or already imprisoned,” she said.

“Many journalists don’t even need to emigrate when they’re being targeted or feel threatened. Some just need some peace for three or four months to put their mind together, and think what they’ve been through and decide whether they should come back or find another solution.”

Erhaim, who currently lives in the UK, said it was also important to think about journalists’ families.

Eritrean journalist Abraham Zere is living in exile in the USA after fleeing his country. He feels the visa proposal would offer journalists in challenging political situations some sense of hope. “It’s so very important for local journalists to [be able to] flee their country from repressive regimes.”

Eritrea is regularly labelled the worst country in the world for journalists, taking bottom position in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index 2021, below North Korea. The RSF report highlights that 11 journalists are currently imprisoned in Eritrea without access to lawyers.

Zere said: “Until I left the country, for the last three years I was always prepared to be arrested. As a result of that constant fear, I abandoned writing. But if I were able to secure such a visa, I would have some sense of security.”

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick is a journalist formerly based in Hong Kong who has recently moved to Taiwan. He has worked as an editor for the Hong Kong Free Press, as well as for the South China Morning Post, Time and The Wall Street Journal.

“I wasn’t facing any immediate threats of violence, harassment, that sort of thing, [but] the environment for the journalists in Hong Kong was becoming a lot darker and a lot more dire, and [it was] a lot more difficult to operate there,” he said.

He added that although his need to move wasn’t because of threats, it had illustrated how difficult a relocation like that could be. “I tried applying from Hong Kong. I couldn’t get a visa there. I then had to go halfway around the world to Canada to apply for a completely different visa there to get to Taiwan.”

He feels the panel’s recommendation is much needed. “Obviously, journalists around the world are facing politically motivated harassment or prosecution, or even violence or death. And [with] the framework as it is now, journalists don’t really fit very neatly in it.”

As far as the current situation for journalists in Hong Kong is concerned, he said: “It became a lot more dangerous reporting on protests in Hong Kong. It’s immediate physical threats and facing tear gas, police and street clashes every day. The introduction of the national security law last year has made reporting a lot more difficult. Virtually overnight, sources are reluctant to speak to you, even previously very vocal people, activists and lawyers.”

In the few months since the panel launched its report and recommendations, no country has announced it will lead the way by offering emergency visas, but there are some promising signs from the likes of Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. [The Dutch House of Representatives passed a vote on facilitating the issuance of emergency visas for journalists at the end of June.]

Report author Yeğinsu, who is part of the international legal team representing Rappler journalist Maria Ressa in the Philippines, is positive about the response, and believes that the new US president Joe Biden is giving global leadership on this issue. He said: “It is always the few that need to lead. It’ll be interesting to see who does that.”

However, he pointed out that journalists have become less safe in the months since the report’s publication, with governments introducing laws during the pandemic that are being used aggressively against journalists.

Yeğinsu said the “recommendations are geared to really respond to instances where there’s a safety issue… so where the journalist is just looking for safe refuge”. This could cover a few options, such as a temporary stay or respite before a journalist returns home.

The report puts into context how these emergency visas could be incorporated into immigration systems such as those in the USA, Canada, the EU and the UK, at low cost and without the need for massive changes.

One encouraging sign came when former Canadian attorney-general Irwin Cotler said that “the Canadian government welcomes this report and is acting upon it”, while the UK foreign minister Lord Ahmad said his government “will take this particular report very seriously”. If they do not, the number of journalists killed and jailed while doing their jobs is likely to rise.

[This week, 20 UK media organisations issued an open letter calling for emergency visas for reporters in Afghanistan who have been targeted by the Taliban. Ruchi Kumar recently wrote for Index about the threats against journalists in Afghanistan from the Taliban.] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

06 Aug 21 | Afghanistan, Belarus, Burma, China, Hong Kong, India, Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117177″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]There are moments as you’re watching the news when it feels as if the world is becoming an increasingly horrible place, that totalitarianism is winning, and that violence is the acceptable norm. It’s all too easy to feel impotent as the horror becomes normalised and we move on from one devastating news cycle to the next.

This week alone, in the midst of the joy and heartbreak of the Olympics, we have seen the attempted forced removal of the Belarusian sprinter Krystina Timanovskaya from Tokyo by Lukashenko’s regime. Behind the headlines, the impact on her family has been obvious – her husband has fled to Ukraine and will seek asylum with Krystina in Poland and there have been reports that even her grandparents have been visited by KGB agents in Belarus.

This served as a stark reminder, if we needed one, that Lukashenko is an authoritarian dictator who will stop at nothing to retain power. And this is happening today – in Europe. Our own former member of staff Andrei Aliaksandrau and his partner Irina have been detained for 206 days; Andrei faces up to 15 years in prison for treason; his alleged “crime” – to pay the fines of the protestors.

In Afghanistan, reports of Taliban incursions are now a regular feature of every news bulletin, with former translators who supported NATO troops being murdered as soon as they are found and media freedom in Taliban-controlled areas now non-existent. Six journalists have been killed this year, targeted by extremists, and reporters are being forced into hiding to survive. As the Voice of America reported last month: “The day the Taliban entered Balkh district, 20 km west of Mazar e Sharif, the capital of Balkh province last month, local radio station Nawbahar shuttered its doors and most of its journalists went into hiding. Within days the station started broadcasting again, but the programming was different. Rather than the regular line-up, Nawbahar was playing Islamist anthems and shows produced by the Taliban.”

Last Sunday, Myanmar’s military leader, Gen Min Aung Hlaing, declared himself Prime Minister and denounced Aung San Suu Kyi as she faces charges of sedition. Since the military coup in February over 930 have been killed by the regime including 75 children and there seems to be no end in sight as the military continue to clamp down on any democratic activity and journalists and activists are forced to flee.

At the beginning of this week Steve Vines, a veteran journalist who had plied his trade in Hong Kong since 1987, fled after warnings that pro-Beijing forces were coming for him. The following day celebrated artist Kacey Wong left Hong Kong for Taiwan after his name appeared in a state-owned newspaper – which Wong viewed as a ‘wanted list’ by the CCP. Over a year since the introduction of the National Security Law in Hong Kong the ramifications are still being felt as dissent is crushed and people arrested for previously democratic acts, including Anthony Wong, a musician who was arrested this week for singing at an election rally in 2018. Dissent must be punished even if it was three years ago.

And then there is Kashmir… On 5 August 2019, Narendra Modi’s government stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its special status for limited autonomy. Since that time residents inside Kashmir have lived under various levels of restrictions. Over 1,000 people are still believed to be in prison, detained since the initial lockdown began, including children. Reportedly 19 civilians have died so far this year caught in clashes between the Indian Army and militants. And on the ground journalists are struggling to report as access to communications fluctuates.

Violence and silence are the recurring themes.

Belarus, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Hong Kong, Kashmir. These are just five places I have chosen to highlight this week. Appallingly, I could have chosen any of more than a dozen.

It would be easy to try and avoid these acts of violence. To turn off the news, to move onto the next article in the paper and push these awful events to the back of our mind. But we have a responsibility to know. To speak up. To stand with the oppressed.

Behind every story, every statistic, there is a person, a family, a friend, who is scared, who is grieving and in so many cases are inspiring us daily as they stand firm against the regimes that seek to silence them. Index stands with them and as ever we shine a spotlight on their stories – so that we can all bear witness.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

05 Aug 21 | Belarus, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117172″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]In the months since the disputed re-election of Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko, the freedom of the press in Belarus has come under increasing attack.

The country’s journalism union, the Belarusian Association of Journalists (Baj.by), has documented more than 500 detentions, hundreds of arrests and fines, and dozens of criminal cases and prison sentences directed against reporters, editors and media managers, including our former colleague Andrei Aliaksandrau.

Almost every independent news and socio-political outlet from the local to the national level has experienced police pressure, searches and confiscations of their professional equipment. Many have been forced to stop publishing or to flee the country in order to work from exile.

In July 2021, the state launched a new wave of repression against independent media outlets and organisations.

Over ten days, security forces carried out more than 70 searches of editorial offices and private homes of employees of national and regional media. As a result, dozens more journalists, editors and media managers joined their colleagues already in custody.

Now BAJ itself is in Lukashenko’s sights.

BAJ is a voluntary, nongovernmental, nonpartisan association that includes more than 1,300 media professionals from across the country. It assists members in realising and developing their professional journalistic activities. Throughout its 25 years of existence, BAJ has also been a leader in promoting freedom of expression and defending media rights.

The organisation has been internationally recognised for its work. In 2004, the European Parliament awarded BAJ with the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, the EU’s highest human rights tribute. In 2011, it received the Atlantic Council’s Freedom Award. In 2020, the organisation was the first recipient of the Canada-UK Media Freedom Award, which recognises individuals and organisations advocating for media freedom.

Over the past year, BAJ has focused on defending and assisting its members whose professional and human rights have been violated by the state’s searches, detentions, beatings, legal and criminal persecution, arrests and prison terms. So it is not surprising that the authorities have launched a repressive campaign targeting BAJ itself.

In June, BAJ was forced to hand over thousands of documents about its activities.

The following month, authorities conducted another search of the office even without the presence of the association’s representatives. It is unknown in respect of which criminal case it was searched nor what was taken from there. They have also sealed the office, meaning employees cannot work there anymore and there is no access to statutory documents.

Now the country’s Supreme Court issued an order for the organisation to be liquidated. This is the same situation which almost 50 other public organisations of Belarus have faced, which have been of benefit for decades to Belarusian society, journalism, the writing community and many other areas.

BAJ’s closure – if the courts agree to the liquidation – will cause serious damage to the Belarusian journalistic community.

Firstly, there will be no legal organisation left in the country that can protect the rights of journalists.

Secondly, the association’s educational hub for journalists will disappear, and many BAJ educational programmes will have to be closed.

Finally, the only legal and recognised institution of journalistic ethical self-government will be destroyed – the BAJ Ethics Commission. In recent years, this was the only body in Belarus that effectively considered issues related to ethics in the media.

Yet even if BAJ is forced to close, it will not disappear.

The support of the international community for BAJ is strong. Journalists and numerous human rights organisations around the world have offered their support to BAJ and its members at this difficult time. BAJ also has outstanding support from the International and European Federation of Journalists, who oppose the liquidation, and have said that if it is closed, the association will remain a member of their organisations.

If the liquidation of the BAJ legal entity is confirmed, the headquarters will make a final decision on how it will work in the future. If it is impossible to continue in Belarus, BAJ will consider working abroad.

BAJ continues the fight. It has already appealed the Ministry of Justice’s liquidation order and the court will consider this on the morning of 11 August.

However, the justice system no longer works properly any more in Belarus. In any other democratic country, the court’s decision would be in favour of the BAJ.

The most important thing, according to BAJ chairman Andrei Bastunec, is that the organisation will continue its work.

“BAJ is not only a legal entity, but an association of like-minded people who see their mission as expanding the space of freedom of speech in Belarus,” he said.

Bastunec says the official registration of the organisation provided, by and large, one advantage: it simplified communication with government agencies. But when the authorities announced its ‘sweep’, advance communication was reduced to zero.

“As strange as it may sound, the deprivation of the BAJ’s legal status by the court will have almost no effect on Belarusian journalism and journalists. Many of them have been forced to go abroad, but continue to work there successfully. The BAJ will continue its work regardless of the court verdict,” he said.

Despite the threat to its existence in Belarus, active members of BAJ are defiant. Many say they will continue working in Belarus as long as possible until the authorities force them to leave the country.

“There is an administrative, bureaucratic reality from which the BAJ can be erased, but there is also a life where the organisation will continue to carry out its mission. The biggest threat to Belarusian journalism is not the deprivation of BAJ registration, but the wave of repression.”

Bastunec says the BAJ team welcomes the solidarity offered by those in the country and abroad.

“It must be understood that the Belarusian authorities today have entered into a fierce confrontation with the ‘collective West’, as they now call the democratic world.”

Yet even if forced to work outside Belarus, BAJ and its members may not be safe. The recent suspicious death of Vitaly Shishov in Ukraine and the attempt to force Belarusian athlete Krystina Timanovskaya to return home after speaking out against her coaches at the Olympics show that Lukahsenko’s tentacles have a very long reach.

Chronology of the repressive campaign against BAJ

9 June The Ministry of Justice launches a major audit of BAJ’s activities.

21 June BAJ receives an official request requiring the organisation to provide thousands of administrative and financial documents on its activities, including lists of its members, covering the last three years. The documents were demanded the same day but the Ministry of Justice later extended the deadline to 1 July. Despite the short time frame, BAJ submitted all the requested documents, with the exception of those seized from the BAJ office during a search by security forces in February 2021.

14 July In the absence of BAJ representatives, security forces raided, searched and sealed BAJ’s office.

15 July BAJ receives an official warning from the Ministry of Justice on the grounds that its regional branches in Brest and Maladzechna had allegedly carried out their activities without having legal addresses. However, this is not true. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Justice considered the failure of BAJ to submit all of the required audit documents, as well as the absence of legal addresses of the regional branches, to be a violation of the country’s legislation and BAJ’s charter. The Ministry demanded that the alleged violations be rectified by the next day.

16 July BAJ informs the Ministry of Justice that the organisation’s office had been sealed by the state and that its representatives had no access to its documents. BAJ therefore requested more time to fulfill the Ministry’s demands after gaining access to its premises.

21 July The Ministry of Justice reports via its social networks that it had already submitted a claim for the liquidation of BAJ to the Supreme Court, allegedly due to the organisation’s failure to rectify the violations and the official warning for repeated violations of the law.

9 August Conversation of the parties in the civil case brought by the Supreme Court on the BAJ appeal against the written warning issued by the Ministry of Justice on 15 July.

11 August Supreme Court will hear the liquidation order against BAJ.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”172″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

04 Aug 21 | Bosnia, News and features, Russia, Serbia, Syria, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117165″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Thirty years separate the beginnings of conflicts in Bosnia-Herzegovina, where I come from, and Syria, where I work now. Bosnia and Syria are the bookends that encompass the three decades when we lived in a world where our collective conscience, eventually, recognised we had a responsibility to protect the innocent, to bring those responsible for war crimes to justice, and to fight against revisionism and denial. Whereas the Bosnian tragedy of the 1990s marked the (re)birth of these values, the Syrian carnage has all but put an end to them.

Nowhere is this sad fact more apparent than in the expansion of disinformation, revisionism and denial about the crimes perpetrated by the Syrian regime against its own people. As a result, disinformation campaigns have become increasingly vicious, targeting survivors, individuals and organisations working in conflict zones.

Coddled by the ever-expanding parachute of academic freedom and freedom of expression, these unrelenting smear campaigns have ruined, endangered and taken lives. They have eroded trust in institutions, democratic processes and the media and sown division in fragmenting democratic societies. Their destabilising effect on democratic principles has already led to incitement to violence. Left unchecked, it can only get worse.

The disinformation movement has brought together a diverse coalition of leftists, communists, racists, ideologues, anti-Semites and fascists. Amplified by social media, their Nietzschean contempt for facts completes the postmodernist assault on the truth. But more important than the philosophical effect is the fact that disinformation campaigns have been politically weaponised by Russia. Under the flag of freedom of expression, they have become a dangerous tool in information warfare.

I know this, because I am one of their targets.

Beyond the fringe

Earlier this year, the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), an NGO of which I am one of the directors, flung itself into the eye of the Syria disinformation storm by exposing the nefarious nature of the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media (WGSPM), an outfit comprising mainly UK academics and bloggers.

The CIJA investigation revealed that, far from being fringe conspiracists, these revisionists, employed by some of the UK’s top universities, were collaborating with Russian diplomats in four countries; were willing to co-operate with presumed Russian security agents to advance their agenda and to attack their opponents; were co-ordinating dissemination of disinformation with bloggers, alternative media and Russian state media; appeared to be planning the doxxing of survivors of chemical attacks; and admitted to making up sources and facts when necessary to advance their cause.

The investigation was a step out of my organisation’s usual focus. For almost a decade, CIJA has been working (quietly and covertly) inside Syria to collect evidence necessary to establish the responsibility of high-ranking officials for the plethora of crimes that have become a staple of daily news. More than one million pages of documents produced by the Syrian regime and extremist Islamist groups sit in CIJA’s vaults and inform criminal investigations by European and American law enforcement and UN bodies. These documents tell, in the organisers’ and perpetrators’ own words, a deplorable story of a pre-planned campaign of murder, torture and persecution, a story that started in 2011 when the Syrian regime began its systematic and violent crackdown on protesters.

CIJA’s work is pioneering and painfully necessary as it ensures crucial evidence is secured, analysed and properly stored when there is no political will or ability to engage official public bodies to investigate the crimes. Our evidence has been described by international criminal justice experts to be stronger than that available to Allied powers holding the Nazi leadership to account during the Nuremberg trials. This makes us dangerous and this makes us a target – both in the theatre of war and in the war on the truth.

Before long, we were in the crosshairs of apologists for Syrian president Bashar al-Assad and, soon after that, in those of the Russian-sponsored disinformation networks.

The weaponisation of propaganda

Propaganda has been the key ingredient of every war since the beginning of time. But its unrelenting advance in the midst of the Syrian war is unprecedented. The beginnings of its weaponisation can be traced back to 2015 when the wheels of fortune turned for Syria as Russia got militarily involved in the conflict. Assad was on the way to winning on the ground but the battle to own the narrative of the war was only just beginning. In its advance, Moscow’s disinformation machinery swept up Western academics, former diplomats, Hollywood stars and punk-rock legends. New outfits and personalities mushroomed, bringing a breath of fresh air to the stale and steady group of woo-woo pedlars and conspiracy theorists from the 1990s.

The WGSPM is one such outfit. Founded in 2017, its most prominent members are Piers Robinson, formerly of Sheffield University; Paul McKeigue and Tim Hayward, of the University of Edinburgh; David Miller, of the University of Bristol; and Tara McCormack, of the University of Leicester. Apart from their shared interest in proliferating pro-Assad, pro-Russian Syria propaganda, between them these professors cover 9/11 truthism, Skripal poisoning conspiracies, Covid-19 scepticism, anti-Semitism and Bosnian war crimes denial.

The modus operandi of disinformation in Syria is simple and borrows from how it was done in Bosnia: sow seeds of doubt regarding two or three out of myriad atrocities committed by the Syrian regime in order to put a question mark over the whole opus of criminal acts overseen by Assad over the past decade.

In Bosnia, according to revisionists, Sarajevo massacres were staged or committed by the Bosnian army against its own people, Prijedor torture-camp footage was faked and the number of Srebrenica genocide victims was inflated. In Syria, according to disinformationists, the Syrian regime’s chemical weapon attacks were staged or committed by opposition groups, footage of children and other civilian victims was faked and the number of those who went through the archipelago of torture camps was inflated.

Syria disinformationists make great use of the postmodernist scepticism about evidence and truth in order to advance their theories. They resort to obfuscation, distortion and alternative evidence. The vision is blurred. Questions are important, answers not so much. Context is irrelevant.

There is not much of a change there from the 1990s. The only marked difference is that today’s approach to advancing disinformation focuses much more on tearing down individuals and organisations working in or reporting on the war. In order to make a lie believable, one must discredit those who endeavour to test the truth.

The WGSPM started by disputing that chemical weapons attacks were conducted by the Assad regime, proffering instead pseudoscientific arguments that the attacks either did not happen, or were staged or committed by opposition groups, potentially with the support of Western imperialist governments. They zoned in on two out of more than 300 documented chemical weapons attacks. But two was enough to start sowing the seeds of doubt among wider audiences.

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) was in the crosshairs as its investigative teams and fact-finding missions returned with findings pointing to the Syrian regime’s responsibility for the attacks over and over again. The OPCW was portrayed to be issuing doctored reports in support of the alleged Western imperialist agenda to overthrow the regime, including by the use of military intervention for which chemical weapons attacks would be a pretext. The disinformationists parroted Damascus and Moscow in whose view all of the alleged chemical attacks were staged on the orders of the West.

The targeting of the White Helmets

A special level of vitriol targeted the White Helmets, a Syrian search and rescue organisation whose cameras record the daily toll of Syrian regime and Russian bombs and chemical weapon attacks on innocent people’s lives as they rush in to pull the victims out of the rubble. They were branded as actors, jihadists and Western intelligence service agents. They were accused with zero evidence of organ-harvesting. The children they pulled out of the rubble were cast as fake or actors. WGSPM members promulgated theories that the White Helmets killed civilians in gas chambers and then laid them out as apparent victims of fake chemical weapons attacks.

The group’s most influential member, Vanessa Beeley, a self-proclaimed journalist residing in Damascus, openly incited and justified the deliberate targeting of the White Helmets, hundreds of whom have died in so-called double and triple-tap airstrikes carried out by the Russian and Syrian air forces. Beeley claimed the White Helmets’ alleged connection to jihadists made them a legitimate target. The jihadists connection itself was a “manufactured truth”. Beeley has spent years producing blogs and twisting the facts to present the White Helmets as aiders and abetters of the extremist armed groups. This falsehood then proliferated in cyberspace, amplified by alternative and Russian state-sponsored media, and eventually parts of these allegations began to stick with wider audiences.

Last year, a study from Harvard University found that the cluster of accounts attacking the White Helmets on Twitter was 38% larger than the cluster of accounts representing their work in a positive light or defending them from orchestrated info warfare.

Soon, Russian state officials started singling out White Helmets’ co-founder James Le Mesurier, branding him as an MI6 agent with connections to terrorist groups. The hounding of this former British soldier was relentless. Le Mesurier was so deeply affected by the relentlessness of the campaign against the organisation, its people and himself that it contributed to the erosion of his psychological wellbeing and, eventually, his death.

The fastest way to erode the credibility of an entity is to discredit its leadership. This is what the disinformation network tried to do with the White Helmets and Le Mesurier. When they started shifting focus to CIJA, the messaging and the mode of its delivery did not change much.

At first, CIJA did not pay attention to the attacks. As with the White Helmets, the coverage of CIJA’s work by the international media was overwhelmingly positive, although with the difference that we were not as prominent in the public eye. But after the New Yorker published a long read in 2016, within days the alternative media and bloggers produced a dozen articles casting doubt over the authenticity or even the existence of the documents in our archive, branding CIJA the latest multi-million-dollar propaganda stunt.

By 2019, things had got more serious. When The New York Times and CNN within days of each other published articles about CIJA’s evidence of Assad’s war crimes, inexplicably it was the Russian embassy in the USA that spoke out first, issuing a statement attacking the media for writing about such an “opaque” organisation. Within 10 days, US online outlet The Grayzone published a lengthy hit piece, calling CIJA “the Commission for Imperialist Justice and al-Qaeda”, claiming we were collaborating directly with Isis and Jabhat al-Nusra affiliates.

It was reproduced in other alternative media outlets and among social media enthusiasts. But, more worryingly, calls from the people who work in the field of international criminal justice and Syria started coming in. These are not the types who would normally believe in conspiracy theories, and the majority of them are apolitical. However, the more the hit piece circulated, the fewer people focused on its source – a Kremlin-connected online outlet that pushes pro-Russian conspiracy theories and genocide denial – and focused instead on what was being said about the people in their field who are so rarely in the media.

Predictably, before long, the allegations raised by the hit piece were being directly or indirectly shared by and referred to on social media by international lawyers and other NGOs in our field. It was a perfect example of the speed and efficiency with which information warfare could penetrate the mainstream.

CIJA and disinformation

In 2020, the WGSPM made it known it was turning its attention to CIJA. The focus, replicating that of the White Helmets attack, was on CIJA founder and director Bill Wiley who was perceived by the conspiracists to be a CIA agent in Canadian disguise working with British money and jihadists to subvert the government of Assad and, in the process, enrich himself. It was one year after Le Mesurier’s death and, by then, the impact the disinformation campaign had on the last months of his life had been well documented.

We would not be sitting ducks. CIJA’s undercover investigation commenced out of fear for the security of its people and operations. Only three out of 150 of us appear in public. Locations of our people and our archives are kept secret. This is not because we are a covert intelligence front but because the threat is real.

Our investigators have been detained, arrested and abused at the hands of both the regime and extremist armed groups. One has been killed. Among the Syrian regime documents in our possession are those that show that Assad’s security intelligence services are looking for our people both inside and outside Syria.

Running investigative teams inside one of the world’s most dangerous countries requires a low profile, independence, access and mobility. The nature of the narrative falsehoods spread by the likes of the WGSPM was such that it threatened each of those requirements.

Being caught in possession of Syrian regime documents in the country would be a death sentence if our people were stopped, either by the regime or by Islamist extremist groups. Linking the organisation to foreign intelligence services or even to jihadist groups makes them easy targets in the theatre of war that is Syria. Allegations of financial or other types of impropriety are a death sentence to organisations that are donor dependent.

This is what makes these disinformation networks dangerous. By proliferating lies and innuendo and obfuscating the reality about organisations and individuals working in the field, they not only threaten to derail the legitimate work we are doing but also directly endanger the lives of the people doing it. This is not what freedom of expression should be about.

The old saying goes, a lie travels halfway around the world before the truth puts its boots on. The influence of disinformation networks today cannot be compared to those of the 1990s. The proliferation of online media outlets, the growing influence of social media, the increasing embrace of alternative facts and multiple versions of truths have all contributed to the dissemination of a skewed picture of what is really happening in Syria.

Even with the constant reporting by the international media of the atrocities the Syrian regime has bestowed on its own people – with thousands of crimes and survivors’ testimonies unrelentingly documented by Syrian and international human rights organisations as well as the UN – Western communities have remained at best on the sidelines in the face of the biggest carnage of this century. The core values of humanity dictate that a collective outcry should have reverberated across the political divide at the sight of gassed children gasping for breath, babies being pulled out of rubble, and emaciated, tortured and decaying bodies strewn around prison courtyards. Yet, by and large, the general population stayed silent. Why? Because the Syrians have been dehumanised on an industrial scale in Western general public opinion.The purpose of disinformation campaigns is to sow the seed of doubt about what is happening, to stoke fear and ultimately to erode trust in democratic processes and human rights values. And that is precisely the effect of the Syria disinformation campaign.

This has been possible only because the revisionists are no longer a fringe group with limited reach. The trajectory of an untruth about the White Helmets just like that about CIJA is very similar: a blog will come out, which will be picked up by a connection in alternative online media, which will then be amplified by Russian state-linked media, which will then be repackaged by Moscow and presented as legitimate facts worthy of discussion in front of the UN Security Council in New York, at the UN in Geneva, and at OPCW State Parties meetings in The Hague. They have even started penetrating parliaments in London, Berlin and Brussels.

With the help of social media, bots and trolls, and in the era of Trumpian contempt for mainstream media, its trajectory can go only upwards.

CIJA’s probe revealed the level of these connections as the Assad apologist from WGSPM Paul McKeigue outlined them in quite some detail in correspondence with our investigators. The campaigns against the White Helmets, the OPCW and CIJA were not isolated attempts to point to inconsistencies in the “mainstream narrative” of the Syrian war. They were an orchestrated attack on what were deemed to be the biggest obstacles to an attempt to whitewash Assad’s crimes.

Although CIJA uncovered the nefarious connections between academics, bloggers and Russian state operatives, the “alternative truth” lives on even when it is proven to be a lie.

Fake news?

For proof, again look at Bosnia. Twenty years ago, Living Marxism magazine went bankrupt after a UK court found that it had defamed ITN and its journalists by claiming the images they recorded in death camps in north-western Bosnia in 1992 were fake. Since then, an international tribunal in The Hague has established beyond reasonable doubt the truth about the macabre crimes that took place in the camps. The journalists’ reports were entered into evidence and withstood rigorous challenges offered by the defence in more than a dozen cases. Yet the claim that this was “the picture that fooled the world” and that the camps were mere refugee centres lives on.

My friend Fikret Alić is the man whose emaciated body behind barbed wire was snapped by cameras on that hot August afternoon in 1992. Thirty years later, he is still tortured by a relentless denial campaign. Weeks ago he was ridiculed on Serbian television by journalists and filmmakers who relied on Living Marxism’s proven lie to back their claims.

It is a never-ending quagmire. As he told Ed Vulliamy, the Observer journalist who reported from the Bosnian camps in 1992: “When those people said it was all a lie and the picture of me was fake, I broke completely. There was nothing they could give me to get me to sleep.”

Living with the nightmare of survival is a lifelong struggle for most. Living with the accusation that what they experienced did not happen condemns them to reliving that torture over and over again.

Mansour Omari, a Syrian journalist who survived a whole year of being bounced around different detention facilities in the Syrian security services’ torture grid, recently wrote that “those who callously deny our torture ever happened are torturers in another guise”. His words are not a poetic metaphor. The psychological and physical suffering for thousands of Fikrets and Mansours subjected to that denial is very much real.

Yet the survivors are effectively told that those whose denial torments them are doing so in the name of free speech and with the aim of challenging injustices. The idea is preposterous. Disinformation encourages discrimination, dehumanisation and prejudice against the victims.

Instead of being denied the platform from which to inflict further pain and incitement, the revisionists are revered and rewarded with peerages and space to spread the poison in the mainstream.

The mainstream media of today is even more reluctant to challenge revisionism than it was in the 1990s. When ITN decided to sue Living Marxism, the debate it ignited in media circles was not about the heinousness of the lie but about whether it was right for a large media outfit to sue a smaller one.

Today’s alternative media go much further than Living Marxism dared to venture. Reports of massacres are challenged by attacking the journalists who bring them. They are claimed to be Western imperialist shills connected to US/UK intelligence services, fabricating reports from Syria with the assistance of Isis or al-Qaeda.

But I have yet to see a mainstream media outlet take steps to defend the honour of its journalists, the integrity of its reporting and the truth in the way ITN did so many years ago. The result? Public trust in the media is in steady decline, with a 20% slump recorded in the UK in the past five years alone.

This is not to undermine the journalists who continue seeking to investigate and understand the actors in the Syrian disinformation network space. But they face more of an uphill struggle to get the space for it from their editors than was the case in the past. The question media management should ask themselves is not if it is unseemly for a large media outlet to defend its journalistic track record by challenging the revisionist lies that make it a target of disinformation. The more important question is whether it is right to let such a falsehood go unchallenged. What impact does it all have in the long run on historic record, on the victims, and on journalistic ethics which include seeking the truth?

Academia, too, has been stunned into inaction as a growing number of university staff abuse their credentials to spread propaganda. Whether gathered in coalitions such as the WGSPM, or working as lone wolves, they have become weaponised agitprop agents of Moscow (in the case of the WGSPM and its affiliates, knowingly and wilfully so, as their members have admitted to be co-ordinating with a variety of Russian diplomats to subvert the work of the OPCW, the White Helmets and others such as CIJA).

Universities are hiding behind academic freedom to explain their lack of action to sanction such wholly unscientific behaviour. The professors and their universities alike claim that these individuals are acting in their private capacity. Yet each one of them links to their university page on the WGSPM website. As plain Paul, Tim, Tara, Piers and David, they would be just another set of fringe conspiracists in the masses. With their full affiliations to prestigious universities listed every time they put their names to a revisionist or disinformationist story, they command credibility.

Fighting the disinformation war

With media and academia becoming major carriers of disinformation, what kind of a history of Syrian conflict is being written?

The perturbing answer of what awaits Syrians and the future discourse about that conflict can be gleaned from what has transpired in Bosnia in the years since. The denial of Bosnian atrocities has not only seeped into the mainstream but is being rewarded at the highest level. In 2019, Peter Handke, a prominent denier of the Srebrenica genocide and supporter of Serb leader Slobodan Milošević, received the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 2020, Claire Fox, who was co-publisher of Living Marxism and continued to deny Bosnia war crimes afterwards, was given a peerage.

What hope is there, then, for the truth about Syria to prevail when Assad apologists are regularly given space in the traditional media, on neo-liberal platforms and within academia? Revisionists such as the WGSPM’s Tara McCormack, who lectures at Leicester University and holds a regular slot on Russia Today and Sputnik, frequently appears on the BBC and LBC, too. The DiEM25 movement, a pan-European organisation whose stated aims are to to “democratise the EU” gives over a whole panel to some of the most vehement Assad apologists, including Aaron Maté who not only denied the survivors their truth but openly mocked them on social media. These are not people who present “diversity” of opinions or ideological or political alignments.

Ultimately, these people, instead of being challenged for their lies and the harm they cause to survivors and others, are being given the space to trickle their pseudoscientific revisionism into the mainstream. It is time to stop giving them a platform. And it is time to challenge them with all lawful means.

It might be unpalatable to read such a proposal in a magazine that stands up against censorship. After all, without freedom of expression and academic freedom we might as well bid goodbye to democracy and human rights. But this crucial value is what revisionists clutch at every time they are called out. In turn, such accusations make most of us uncomfortable to take the necessary steps to tackle a growing problem.

Truth-seeking is supposed to be at the core of universities’ existence, but revisionism and denial do not constitute truth-seeking. Academic freedom should allow for robust debate and challenge the conventional wisdom. But it should not allow for incitement of hatred or slandering of victims, survivors, journalists and others.

Truth matters because disinformation destroys lives, as history has taught us. It torments people: from Fikret Alić to Mansour Omari to James Le Mesurier, to countless others whose names we will never learn.

Disinformation exposes those such as the White Helmets or CIJA working in conflict situations to additional risk. Labelling journalists as security intelligence or jihadi sympathisers puts a target on their backs. The unrelenting advance of disinformation must be stopped before more harm is done.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

03 Aug 21 | Magazine, News and features, United States, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117105″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

This story should be told by Reality Leigh Winner my sister. I am telling her story because Reality, despite being released from federal prison and in home confinement, is still not allowed to speak to journalists about her case. Reality is being censored and silenced by a government that is afraid of what she might say.

Reality was incarcerated on 3 June 2017. By the time she was released from federal prison in June, she had spent most of the last half of her 20s in prison. For a commended US Air Force veteran with no criminal record, no history of violence, no intent to harm anyone, no plan to financially benefit from a crime and only the best of intentions, every day that she has spent in prison has been a travesty.

As a National Security Agency contractor in 2017, Reality anonymously mailed a classified document detailing a Russian government spear-phishing campaign directed at the voting systems in 21 states around the time of the 2016 US presidential election. She sent the document to a media organisation called The Intercept, which has been known to solicit information from whistleblowers.

Many people ask me why Reality leaked the document. She had everything to lose and nothing to gain. I can speculate that she thought that the American people desperately needed to know that their voting systems were targeted by Russia so that steps could be taken to make the next presidential election more secure.

She helped achieve that goal: the 2020 election was the most secure presidential election in US history.

I can also speculate that Reality wanted to set the record straight about Russian interference in 2016. As the person who knows her best, I can say that she did not intend to harm the USA or undermine national security by leaking the document and, in fact, there is no evidence that the disclosure tipped off Russian hackers to “sources and methods” of US intelligence.

However, it is possible that I will never really know Reality’s true reasons or motivations for leaking the document because she is not, and never will be, allowed to speak about it.

[/vc_column_text][vc_btn title=”Join Brittany Winner at our virtual magazine launch on Tuesday 3 August: Book a free ticket NOW” color=”danger” size=”lg” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.eventbrite.co.uk%2Fe%2Fwhistleblowers-the-lifeblood-of-democracy-tickets-164316941395″][vc_column_text]

Since she was charged with “unlawful retention and transmission of national defence information” under the Espionage Act of 1917, she has not been allowed to talk about the document or even say during her trial why she leaked it. The jury or judge were also not able to know the contents of the document or whether the release of the document actually harmed or exposed the USA. The only two factors pertinent in a trial under the Espionage Act are whether the individual is authorised to share the information and, if not, whether the individual has shared the information with someone who does not possess a relevant security clearance.

Reality was convicted almost certainly because of her alleged confession in the interrogation conducted by armed FBI agents in her home who did not inform her of her rights while a warrant was being served on her home, her car and on her.

As part of a plea deal, she pleaded guilty to a single charge and received a record-breaking 63 months in federal prison followed by three years of supervised release. Her plea deal also broadly prohibits her from future “communication of information relating to classified subject areas” that she had experience in from her time in the Air Force or while employed as an NSA contractor “without first obtaining the express written permission” from the US government.

The plea paperwork says: “This prohibition includes, but is not limited to, any interviews… papers, books, writings… articles, films, or other productions relating to her or her work as an employee of or contractor for the United States Government.”

The language of the plea agreement appears intentionally vague, as though even a casual mention of Russia (which could be construed by the US government as a “classified subject area”) by Reality could violate it and send her straight back to federal prison.

Moreover, the exceptionally vague reference “to her or her work” almost seems laughably broad – as if she is no longer allowed to talk about herself or her personal life story. If these stipulations in the plea agreement do not constitute censorship of a US citizen by her government, I do not know what would.

Reality was released from federal prison in June 2021 for good behaviour which is not surprising because she is a good person. However even thought her physical body is no longer behind bars the draconian prohibitions on her speaking to the media continue. Therefore I think that Reality’s mind is still stuck in prison and she is far from free.

As someone who pled guilty to a federal crime, Reality is facing more than just the loss of the right to speak freely. She will also have a criminal record that will follow her for the rest of her life, making it more difficult for her to seek gainful employment and enjoy the rights and freedoms that Americans take for granted.

She has also, ironically, lost the right to vote, which is especially harsh considering that she helped protect the votes of her fellow Americans. Reality will continue to suffer the unfair consequences of her brave and selfless actions for the rest of her life without intervention from President Joe Biden

Although we cannot restore the more than four years of her young life Reality Winner spent incarcerated by the time of her release, we can attempt to right this grievous wrong by appealing to President Biden to grant Reality Winner a full pardon.

With a presidential pardon, Reality could live her life without the burden of a felony conviction on her record.

A pardon would also end the continued censorship of Reality Winner following her release and finally allow her to speak out about why she leaked the document exposing the truth about Russia’s interference in the 2016 election. The American people deserve to know the brave patriot who stood up for them against her own government.

For President Biden, who appears committed to righting the wrongs of the previous administration, pardoning Reality Winner seems to be the least he should do, considering that Reality’s bravery is one of the reasons that Biden was elected as US president in a free and fair US democratic election. We ask the President to carefully consider Reality’s case and pardon Reality Winner.

[/vc_column_text][vc_btn title=”Join Brittany Winner at our virtual magazine launch on Tuesday 3 August: Book a free ticket NOW” color=”danger” size=”lg” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.eventbrite.co.uk%2Fe%2Fwhistleblowers-the-lifeblood-of-democracy-tickets-164316941395″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Jul 21 | Cuba, Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mural showing Che Guevara in Havana, Cuba

Index on Censorship was established half a century ago to be a voice for those writers and scholars who lived under repressive regimes. We were formed to be a space to publish their works and, just as crucially, to be their advocates at home and abroad. Using their words and experiences to shine a spotlight on the realities of authoritarian regimes wherever they were a threat to free expression.

Since our launch we have documented incidents in countries as diverse as Niger and Belarus, China and Pakistan, Palestine and Myanmar. We campaign for the right to free expression wherever in the world it is being undermined, including in Europe and the US. Most importantly, we support brave journalists, activists, artists and writers wherever and whenever we can.

Index is not driven by an ideology, we care little if a regime claims the mantle of the left or right. Rather, our actions are guided by the deepest of convictions that totalitarianism and repression anywhere in the world undermine our collective rights to free expression. In other words – an attack on one is an attack on all – and we are on the side of those being persecuted.

Which brings me to Cuba. Index first wrote about the Cuban regime’s efforts to undermine free speech and free expression in 1980. In the intervening 40 years we have commissioned dozens of journalists, dissidents and artists to report on the lived reality on the ground. I think it’s fair to say that peoples lived experience in Cuba has not changed for the better in that time.

This month we saw yet more protests on Cuban streets, with people protesting in at least 15 different towns and cities, from San Antonio de los Banos to Palma Soriano. It has been reported that five people were killed in the protests. More than 500 people are currently missing thought to be detained by the regime, according to the Center for a Free Cuba. Many more have been arrested and charged. Such are the restrictions on the ground that we honestly don’t know how many people have been arrested, what they have been charged with and where they are.

The reality is we know more about is happening to protestors in Myanmar than we do in Cuba. Journalists are being routinely arrested and threatened. And the regime is focused not on responding to the issues which have sparked the dissent – but rather initiating a crackdown. This is not a utopian society – it is a repressive regime, which is seeking to silence those who disagree.

The Cuban government have done an amazing job in romanticising their actions – building a global movement of solidarity based on the images of Che Guevara and the socialist speeches of Fidel Castro. But the reality has never matched this romantic vision. RSF has ranked Cuba 171 of all countries in the 2021 World Press Freedom Index. The Committee to Protect Journalists ranks Cuba as one of the 10 most censored countries in the world. And Freedom House designates Cuba as ‘not free’ – scoring 13 out of 100 for political rights and civil liberties.

Cuba is a repressive regime – it works to supress the human rights of its citizens and Index on Censorship will continue to support Cuban dissidents as they seek to shine a light on the authoritarian actions of the Cuban regime.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Jul 21 | Magazine, United States, Vietnam, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116892″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, whose leaks 50 years ago this summer aimed the spotlight at the US government’s secret escalation of the conflict in Vietnam over the course of five presidential administrations, is clear that such shattering revelations should not happen just once in a generation.

“There should be something of the order of the Pentagon Papers once a year if not more often,” he said.

Ellsberg speaks to me over Zoom from his home in California’s Bay Area shortly after celebrating his 90th birthday. His mind is as sharp as ever and his belief that government wrongdoing should be uncovered is as strong as it was more than five decades ago. His leaking of thousands of pages of critical failings of presidents from John F Kennedy through to Richard Nixon in US involvement in Vietnam – the Pentagon Papers – proved damning, and ultimately led to Tricky Dicky’s impeachment.

Instead of such yearly disclosures of wrongfully withheld information, Ellsberg says it took 39 years before there was a leak of a similar scale – Chelsea Manning’s disclosure of hundreds of thousands of US diplomatic cables and their subsequent publication by Julian Assange on Wikileaks in 2010.

[/vc_column_text][vc_btn title=”Join Daniel Ellsberg at our virtual magazine launch on Tuesday 3 August: Book a free ticket NOW” color=”danger” size=”lg” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.eventbrite.co.uk%2Fe%2Fwhistleblowers-the-lifeblood-of-democracy-tickets-164316941395″][vc_column_text]

On US foreign policy

Ellsberg is of the belief that the world needs a new generation of whistleblowers to keep his government in check.

“US foreign policy is largely conducted as a covert, plausibly denied, imperial policy,” he said.

“We deny we are an empire, and we deny the means we use, the means which every empire uses to maintain its hegemony – torture, paramilitary invasion, assassination. This is the standard for everybody who seeks a global influence over countries and gets involved in regime change the way we do.”

But a career as a whistleblower is unlikely to be recommended to young people emerging from education any time soon.

“I have never heard of anyone wanting to be a whistleblower,” said Ellsberg. “People admire it when they see it, but it is a strange career to set out on – and it’s not a career because you generally only get to do it once. Employers believe you won’t tell their dirty secrets no matter how criminal, illegal, wrongful or dangerous your bosses may be.”

He says that people entering the world of work for the first time need to understand what they are signing up for.

“When young people sign agreements [with their employers] under which they will be asked to not reveal any secrets they become privy to in their job they should take into account that they don’t really have a right to keep that promise in all circumstances,” he said. “Circumstances may well arise where it is wrong to keep silent about information that has come to your attention because other lives are at stake, or perhaps the constitution is being violated and it is wrongful to keep that promise.

“It doesn’t occur to you that you could be asked to take part in very wrongful or criminal activities. In your eyes you are not joining the Mafia, yet you make a promise of secrecy like the Mafia without knowing what you are going to be asked to do. This is why you should have your fingers crossed when you make that promise.”

Ellsberg relates being invited to a meeting in Stockholm to give an award to Ingvar Bratt, who had exposed illegal sales by arms dealer Bofors.

“Bratt told me that he was explaining to his young son – who was 10 or so – that he was meeting me and explained what I had done. He said to his son: ‘Wasn’t that a good thing to do?’ His son said very soberly: ‘Oh no. He shouldn’t have done that; you should never break a promise’. That is how we are all brought up.

“Young people should remain open to the idea that you may be called on to risk your job, your career, your relationships with other people by telling the truth even if you have promised not to do that. It is very unusual advice for young people to hear; it will not improve their career prospects, but it will possibly save a lot of lives.”

On what distinguishes whistleblowers

Ellsberg is in regular contact with other whistleblowers – a club with a very exclusive membership.

“Whistleblowers believe themselves to be quite ordinary,” he said. “They don’t think that what they did is particularly unusual. They think what they did was the thing anyone would have done in the circumstances.

“But stepping back from their views, it is very unusual for people to do what they did in those circumstances. In almost every case their colleagues knew what was happening and that [the wrongdoing] should be known, but they did not ask themselves if they should be the one to tell.

“There is something unfortunately quite rare about whistleblowing, and that is not good for the future of our species. It means that when terribly dangerous processes are at work, like wrongful wars or the climate crisis, we can’t count on people to step forward and tell us what we need to know.

“Very few people get beyond the point of saying ‘This should be known’ to the point of saying ‘No one else is going to do it, so I have to do it’. That turns out to be an almost unpredictable reaction. It is a matter of personal responsibility and moral courage.”

Moral courage is a vital attribute of a whistleblower, since being ostracised is a frequent outcome.

“People will do almost anything and go along with anything rather than be expelled from a group that they value,” said Ellsberg.

On Assange and Manning

But being cast out is often the least of the worries of would-be whistleblowers, as the act comes with significant costs.

“Chelsea Manning said she was willing to face life in prison or even death,” said Ellsberg. “[Edward] Snowden said at one point there were things worth dying for and he hadn’t been killed for it yet, but he was at considerable risk of that – and it could still happen.

“The government does everything it can to magnify those costs both for the whistleblower and anyone who might want to imitate her or him. There is the stigma of being called crazy, being called criminal. The government really goes into trying to defame the whistleblower in different ways, and often quite successfully.