09 Apr 21 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Photo: Epyc Wynn/Pixanay

I think two of the most unfashionable words in the political sphere at the moment are nuance and context. As a former politician, I completely understand why controversial and provocative statements win out; why polar positions make more entertaining viewing; why pitting people at odds with each other is more likely to inspire ongoing debate and will boost the number of Twitter likes and comments.

In other words, I know why some politicians and journalists are seeking to polarise. It boosts their profile, ensures that someone, somewhere will consider them relevant and for some even ensures that they have a payday.

But the question for me at least, is what cost is this having to our public space? Where is the place for debate rather than argument? How can we build consensus and solidarity if all we’re doing is shouting abuse at each other?

Some of the most contentious debates currently occurring in democratic societies seem to have descended into virtual screaming matches. No one is listening to each other, no one is seeking to find a middle ground and seemingly few people are seeking to build bridges – our collective focus at the moment seems to be to tear each other down.

Of course, the reality is this has always been part of our political discourse. There is a healthy tradition of challenge in our public space. But… my concern is it is no longer on the fringes of our national conversations, it now dominates and the damage that it is doing is untold.

In the last week, we have seen academics compared to the KKK, a trans writer attacked for being long-listed for a literary prize for women and a new narrative on intersectional veganism which attacks other vegans for not considering the role of white supremacy in their eating habits.

I am not saying that people don’t have the right to these views – of course they do. Index on Censorship exists to ensure everyone’s rights to free expression. But that doesn’t mean that our words and deeds don’t have impact or consequence.

We witnessed in America only this year where this form of populist politics can lead to, at the extreme end – the storming of the Capitol. This week we’ve riots on the streets of Northern Ireland, again. Anti-Chinese hate crime has spiked post-Covid. In Belarus, Hungary and Poland we witness daily the appalling impact of the combination of this political polarisation and authoritarian-leaning governments. Words have consequence.

Index was launched half a century ago to provide a published space for dissidents to tell their stories and to publish their works. As we matured we provided a platform for people to debate some of the most contentious issues of the day, from the Cold War to fatwa to vaccine misinformation. We’ve done this in the spirit of providing a genuine space for free expression, a home to ensure that the hardest issues are discussed in an open, frank but measured way. That there is a space for actual debate and engagement. It is this tradition that we seek to emulate – which is why our magazine features considered commentators and thinkers tackling some of the thorniest issues of the day.

We all need a little nuance and context in our lives.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

01 Apr 21 | Awards, Fellowship 2021, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116532″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Artist Anish Kapoor, campaigner Ailbhe Smyth and writer Fatima Bhutto are to join a panel of judges to decide Index on Censorship’s 2021 Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship winners.

Since 2001, the Freedom of Expression Awards have celebrated individuals or groups who have had a significant impact fighting censorship anywhere in the world.

Awards are offered in three categories: Arts, Campaigning and Journalism. Anyone who has had a demonstrable impact in tackling censorship is eligible and nominations are open to all. Winners join Index’s Awards Fellowship programme and receive dedicated training and support.

Anish Kapoor is considered one of the most influential sculptors working today. He was born in Mumbai in 1954 and lives and works in London. He won the Turner Prize in 1991 and, in 2013, he received a knighthood for services to the arts.

Kapoor said, “Index on Censorship does vital work to keep the freedom of the press and our freedom of expression and thereby protects our right to protest, our right to disagree and our need to hold government to account. I applaud Index on Censorship for the work it does with artists, journalists, lawyers and many others to help to ensure that the human spirit in us is kept alive.”

Ailbhe Smyth was the founding head of women’s studies at University College Dublin and is a long-time feminist and LGBT activist.

Smyth said, “At this time of intense global crisis – human and environmental – and with democracy itself under threat in so many parts of the world, it is all the more vital for us to stand up for hard-won human rights, for equality and for justice for all. The right to express ourselves freely is, I believe, fundamental to our human existence and must be both celebrated and, wherever necessary, defended with spirit and determination.”

Fatima Bhutto was born in Afghanistan and grew up between Syria and Pakistan and is the author of several works of fiction and non-fiction, most recently The Runaways and New Kings of the World.

The judges will be joined by Index on Censorship chief executive, Ruth Smeeth, and the panel will be chaired by Trevor Phillips.

Smeeth said, “2020 has seen some horrendous attacks on global free expression, which went underreported due to the realities of Covid-19. Our inspirational judges have big decisions to make this year about who we reward for standing up for our basic right to free speech.”

Previous judges include digital campaigner and entrepreneur Martha Lane Fox, Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, Harry Potter actor Noma Dumezweni, novelist Elif Shafak and award-winning journalist and former editor-inchief of Vanity Fair and The New Yorker Tina Brown.

This year’s winners will be announced at a gala celebration in London on 12 September 2021.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

01 Apr 21 | China, Hong Kong, Media Freedom, Opinion, Ruth's blog, Taiwan

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Photo: PublicDomainPictures

The awful actions of the Chinese government over the last month have dominated our news agenda. The collective actions of the government and their outliers have been designed to silence dissent, to intimidate and to bully.

They have repeatedly attacked core democratic principles both at home and abroad, undermining fair political participation. They’ve arrested democracy activists, changed the law to restrict electoral access to the Hong Kong Legislative Council to sanctioned ‘patriots’ otherwise known as the allies and friends of the Government of China.

The ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has also sanctioned British parliamentarians and activists for daring to speak out about the acts of genocide, happening as I type, in Xinjiang province against the Uighur community. The CCP chose not to target members of the British Government nor key businesses with sanctions.

Instead, it sent a political message and targeted backbench Conservative MPs, two think-tanks and an academic, those who had been most vocal in exposing the actions of the CCP in both Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia. This was a move intended to silence criticism not impose economic sanction, a clumsy and ineffectual effort to restrict free speech outside China’s borders.

This week, these aggressive actions by the CCP culminated with yet another attack on media freedom when the BBC’s lead China correspondent, John Sudworth, was forced to relocate with his family from Beijing to Taiwan after a campaign of state-sanctioned threats and intimidation. Sudworth and his wife, a fellow journalist for the Irish RTE, Yvonne Murray, were faced with no other option than to leave after months of personal attacks in Chinese state media and by Chinese government officials. They will both continue to report on events in China from Taiwan.

The harassment of international journalists in China (and now in Hong Kong) is becoming normalised, with dozens of journalists having to leave in recent months; threats of visas being withheld are now commonplace. This is simply unacceptable.

China seeks to be a loud voice on the global stage – they need to live up to their commitments under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They need to remember they are signatories to Article 19 and that media freedom and free expression are protected rights.

Index stands in solidarity with John and Yvonne.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

31 Mar 21 | News and features, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116514″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]An author of a government report into the handling of public protests has expressed her serious concerns about the independence and impartiality of the police watchdog. The report from Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary looked at policing in the wake of the Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion protests, was published on 11 March 2021 and backed Home Office proposals for tightening up the law. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill which followed sparked protests across the country.

Alice O’Keeffe, who worked as an associate editor at the HMIC, feared the conclusions may have contributed to the crackdown on the vigil for Sarah Everard on Clapham Common in south London. The 33-year-old’s killing provoked a national outcry in the UK about violence against women. Ms O’Keeffe was removed from the team tasked by Home Secretary Priti Patel to report on the policing of the vigil itself after she expressed her view that the “handling of the vigil was completely unacceptable and disproportionate.”

In its report, the HMIC concluded the police acted appropriately in handcuffing and arresting women protestors at the vigil, although it recognised coverage in the media had been a public relations disaster.

In a letter to HMIC head Sir Tom Winsor, seen by Index on Censorship, the civil servant raised her “serious and urgent concerns about breaches of the civil service code” during the earlier inspection into public protests. She raised questions about how the inspection team could be impartial when she was the only member who was not from a policing background. The letter makes a number of serious claims about the impartiality of the inspectorate:

- The civil servant was the only person on the team from a non-policing background, apart from two human rights lawyers who sat in on some discussions.

- A serving Chief Inspector from the Metropolitan Police sat on the team during the fieldwork evaluation even though this was the force originally responsible for demanding the new powers.

- There were only two women on the team of 12 (although a further woman joined later to work on case studies).

- Although a significant part of the inspection concerned the policing of Black Lives Matter protests, only one member of the team of 12 was from an ethnic minority background.

- There was no one with a specialism in equality and race on the team.

- The threat from extreme-right wing groups was not considered.

- The team demonstrated consistent bias against peaceful protest groups, drawing comparisons between them and the IRA.

- The report misrepresented public opinion on the policing of protest.

The civil servant claimed the inspectorate decided to back the government’s proposals before fieldwork has been completed. She quoted correspondence between the inspectorate and the Home Secretary from late 2020 which said the government’s proposals “would improve police effectiveness (without eroding the right to protest) and would be compatible with human rights laws. Moreover, measured legislative reform in these respects would send a clear message to protestors and police forces alike about the limits of the right to protest”.

In her letter to Sir Tom Winsor, the civil servant claimed: “The purpose of the report was not to collect evidence and then make a decision, but rather to collect evidence to support the decision that has already been made.”

Ms O’Keeffe has worked as journalist at the Guardian, the Observer and the New Statesman. She previously worked at the Equalities and Human Rights Commission.

In a statement the inspectorate confirmed it was evaluating Ms O’Keeffe’s observations. However, it said that as an editor “she was not privy to all the work which assessed and weighed the evidence in the inspection”. The final judgment was made by one of the inspectors of constabulary, it said, and approved by the board of the inspectorate.

The statement went on to explain that a thorough legal analysis carried out by external counsel had been completed by the time the letter referred to by Ms O’Keeffe was sent to the Home Secretary. No final judgement was made until fieldwork into the policing of protests had been concluded and the Home Secretary was informed the initial judgement was provisional.

HMIC said its inspection teams always include seconded police officers and that officers from the Metropolitan Police were often used. It denied peaceful protestors were equated to the IRA.

The statement concluded: “The Clapham inspection was entirely objective as is apparent from the report just published. Ms O’Keeffe was not put on the Clapham report because, by her own acknowledgement, she had already made up her mind what the conclusions should be before any evidence had been obtained.

“The independence of the inspectorate has always been conspicuous. It is led by Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Constabulary whose reputation for independence goes back many years.”

Read extracts from the letter and why Index defends the right to protest even during a pandemic.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

31 Mar 21 | United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The following are extracts from a letter to Sir Tom Winsor, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, from Alice O’Keeffe, an associate editor who worked on the HMIC report, Getting the balance right: An inspection of how effectively the police deal with protests, which was published on 11 March 2021. The subheadings are provided by Index to help guide you through the main points. Read the news story here.

Dear Sir Tom,

I am writing to raise serious and urgent concerns about breaches of the civil service code during a project I was recently involved in as an associate editor for Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, an inspection into protest policing. The report from the inspection was published on 11 March 2021, and I was involved in drafting and editing the report and other materials related to the inspection from October 2020-March 2021.

.

.

.

The protest policing inspection

The inspection took place in response to a letter from the Home Secretary Priti Patel, on 21st September 2020, asking the inspectorate to look at whether the police needed more legal powers to deal with protest, in response to disruptive protests by Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter, among others. The inspection lead…asked me to edit the report.

.

.

.

The protest policing report

A foregone conclusion?

Early on in the team’s discussions about the inspection, it became clear that the authors of the report had already decided to back the legislative changes proposed by the Met Police and the Home Secretary, which were to be put forward as part of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. The purpose of the report was not to collect evidence and then make a decision, but rather to collect evidence to support the decision that had already been made.

There is evidence for this in the letter that I helped to draft from [HMIC] to the Home Secretary, which we began to work on in early November 2020, before the fieldwork stage of the inspection was complete. It said the following:

“We believe all five proposals would improve police effectiveness (without eroding the right to protest) and would be compatible with human rights laws. Moreover, measured legislative reform in these respects would send a clear message to protesters and police forces alike about the limits of the right to protest.”

The Home Secretary replied on 7 December:

“Thank you for your letter… Protests have proved a significant challenge over the last year and I am keen to ensure that the police have the powers and capabilities they need to help address the disruption they face. Your findings will help me to do that.”

This was before the fieldwork phase of the inspection had been completed, discussed and evaluated.

Impartial and independent?

The team was not impartial or independent – and it definitely was not balanced in terms of backgrounds and perspectives. …a serving Chief Inspector for the Metropolitan Police, sat on the team through all the fieldwork evaluation discussions…The Metropolitan Police force was originally responsible for requesting these new powers from the Home Secretary, so I was surprised that a senior serving officer from that force was now acting as an “impartial civil servant” on the question of whether his own force’s requested legislative proposals should be enacted.

Diverse?

Although the inspection very largely concerned the policing of Black Lives Matter protests, there was only one ethnic minority member of an inspection team of 12. There were only two women, including me, although one more joined in the later stages to do some case studies.

I repeatedly [raised] concerns about this, saying that as we did not have anyone with a specialism in equality and race on the team, we might have a “blind spot about race”. I suggested to the team leader… that we should send the report out for external review by a specialist in race and policing – he said there wasn’t time to do that, as the report needed to be published before the Bill came to Parliament for its second reading. On my insistence he did eventually – only days prior to publication – say that he would send it to the Black Police Association to review.

Anti-protestor bias?

In various exchanges I became aware that senior team members held views that were biased against protest groups. For example, in the early stages of the inspection [REDACTED] told me that he had a case study he wanted me to look at, of an individual who he felt should be banned from protesting at all… I assumed that this individual must be a violent offender of some kind. However [REDACTED] told me that the individual in question was one of the founders of…Extinction Rebellion.

[REDACTED] asked for my feedback on the case study. I said that I didn’t think we should include it in the report, as the case would polarise opinion. I made the point that we all needed to keep our personal biases in check. He replied: “So, the following questions spring to mind: If we were writing this report during the ‘troubles’, would it be acceptable for us to show bias against the IRA? If not, what about showing bias against the bombers in particular? In 2020, would it be acceptable to denounce the IRA?”

Reflecting public opinion?

The report presented a skewed account of public opinion on protest policing, by only including select results from the survey that the inspectorate commissioned on the issue. The figure quoted prominently in the report is that “for every person who thought it acceptable for the police to ignore protesters committing minor offences, twice as many thought it was unacceptable.”

However, within the full survey there was a much more mixed response to the issue of how firmly the police should deal with protests. Sixty per cent of people thought it was unacceptable for the police to use force against non-violent protesters, for example. It was unclear to me why this finding should not be of equal importance.

The correct focus?

Late in the report drafting process a member of the team sent me a report, published in July 2020, by SAGE into public order and public health. It set out many concerns that [government scientific advisors] SAGE had about policing protest in the context of the pandemic. The SAGE report makes it very clear that the public order threat comes from both BLM-type protests inspired by racial inequality, and from the extreme right-wing (XRW).

The report says: “XRW groups are coalescing and mobilising at a scale not witnessed since the early EDL protests around 2010. There is a substantial overlap between some of the issues foregrounded by these groups (e.g. protection of heritage, memorials) and much larger sections of the population, e.g. among veterans… Large-scale confrontations provoked by the XRW in London and then subsequently in Glasgow, Newcastle and other cities were partly responses to the previous actions of hardcore elements of BLM and the anti-Fascist movement and perceptions of weakness among the police.”

.

.

.

At no point throughout the whole process of putting the protest policing report together had the team ever discussed the public order threat presented by right-wing groups. I sent an email to [REDACTED] on 12 February saying that I felt “we have missed a ‘piece of the puzzle’ when it comes to the rise of the far right.” He said he would consider this, but it was very late in the process and nothing was ever done about it.

In the published report, the far-right are only mentioned once, on p.130. This is the section in which the authors argue in favour of aligning legislation on processions and assemblies, giving the police the power to ban assemblies. It becomes clear at this point that in fact this power is – contrary to the report’s exclusive focus on other protests – much more likely to be necessary in dealing with far-right protests.

The report says: “We learned that, between 2005 and 2012, Home Secretaries signed 12 prohibition (banning) orders on processions. Ten of these were associated with far-right political groups. The other two were associated with anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation groups.”

Events after publication

The headline finding of the report into protest policing was that the balance had tipped “too readily in favour of protesters.” It said that a “modest reset of the scales is needed” away from the rights of protesters, and towards the rights of “others”.

The weekend following the report’s publication, the vigil to mark Sarah Everard’s murder took place in London.

I wrote to [REDACTED] on Sunday morning, saying that I felt the inspectorate had serious questions to answer around whether our protest policing report had “contributed – albeit unintentionally – to an environment in which the Met felt at liberty to prohibit, and then clamp down forcefully on, a peaceful protest by women, against the murder of a woman by a serving police officer.”

I added that I hoped the inspectorate would “make it clear to the Met that its handling of this vigil was completely unacceptable and disproportionate.”

On Monday morning, I received a phone call from my manager to say that the inspectorate had been commissioned by the Mayor of London and the Home Secretary to inspect the behaviour of the Met at the Sarah Everard vigil. He asked me to edit it. I said that I would, but I wanted the team to know that as an editor I would need to ask robust questions about the role of our previous protest policing report in the decisions that had been made by the Met Police that night.

Later that day, I received a follow-up email from my manager to say that [REDACTED] had requested another editor, as he felt “he needed an editor who’d be able to approach this job with an open mind. Based on your email, he didn’t feel that would be possible.” I was replaced by [an] editor with no background in protest policing work.

I acknowledge that, in shock at the events at the Sarah Everard vigil, I expressed the view that the Met had acted disproportionately. This was, and remains, my personal view. I regret making that comment and acknowledge that it did not demonstrate the impartiality that I have always upheld in the context of my role.

However, I believe that I was raising important concerns about a conflict of interest, and the impact of the previous report.

.

.

.

I am a committed civil servant and as such I feel it is urgently necessary for the Inspectorate, and the Civil Service Commission, to address some of these issues, both in terms of this immediate inspection, and in the longer term. Much more needs to be done to ensure proper independence, which means a clear separation between the Inspectorate, the police and other institutions such as the College of Policing. It also means working much harder to ensure that the staff on inspection teams have a diverse mix of backgrounds and perspectives, and that discussions and processes can be truly free, fair and impartial.

Yours faithfully,

Alice O’Keeffe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Mar 21 | China, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116480″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Last week, the Chinese government outlined sanctions against nine British individuals and three organisations for daring to speak out about what is going on in Xinjiang.

Those affected by the sanctions are former Conservative party leader Iain Duncan Smith, Tom Tugendhat, chair of the foreign affairs select committee, Nus Ghani from the business select committee, Neil O’Brien, head of the Conservative policy board and China Research Group officer, Tim Loughton of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, crossbench peer David Alton, Labour peer Helena Kennedy QC and barrister Geoffrey Nice.

The only individual not from the political sphere is Dr Joanne Smith Finley, Reader in Chinese studies at Newcastle University.

The organisations include the China Research Group, the Conservative Human Rights Commission and Essex Court Chambers.

China made the move after the British government imposed sanctions on four Chinese officials and one organisation last Monday: Zhu Hailun, former secretary of the political and legal affairs committee of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR); Wang Junzheng, deputy secretary of the party committee of XUAR; Wang Mingshan, secretary of the political and legal affairs committee of XUAR; Chen Mingguo, vice chairman of the government of the XUAR, and director of the XUAR public security department; and the Public Security Bureau of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps – a state-run organisation responsible for security and policing in the region.

A statement from Tom Tugendhat and Neil O’Brien on behalf of the China Research Group said, “Ultimately this is just an attempt to distract from the international condemnation of Beijing’s increasingly grave human rights violations against the Uyghurs. This is a response to the coordinated sanctions agreed by democratic nations on those responsible for human rights abuses in Xinjiang. This is the first time Beijing has targeted elected politicians in the UK with sanctions and shows they are increasingly pushing boundaries.

“It is tempting to laugh off this measure as a diplomatic tantrum. But in reality it is profoundly sinister and just serves as a clear demonstration of many of the concerns we have been raising about the direction of China under Xi Jinping.”

Commenting on China’s decision, foreign secretary Dominic Raab said: “It speaks volumes that, while the UK joins the international community in sanctioning those responsible for human rights abuses, the Chinese government sanctions its critics. If Beijing want to credibly rebut claims of human rights abuses in Xinjiang, it should allow the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights full access to verify the truth.”

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said, “The MPs and other British citizens sanctioned by China today are performing a vital role shining a light on the gross human rights violations being perpetrated against Uyghur Muslims. Freedom to speak out in opposition to abuse is fundamental and I stand firmly with them.”

Newcastle University academic Dr Joanne Smith Finley believes she has been sanctioned because of her “ongoing research speaking the truth about human rights violations against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang”

“In short, for having a conscience and standing up for social justice,” she said.

She said, “That the Chinese authorities should resort to imposing sanctions on UK politicians, legal chambers, and a sole academic is disappointing, depressing and wholly counter-productive.”

Dr Smith Finley has studied China for many years.

“I began my journey to become a ‘China Hand’ in 1987, when I enrolled at Leeds University to read modern Chinese studies. My first year spent in Beijing in 1988-89 – during which I also experienced the ‘Tianan’men incident’ – ensured that China entered my bloodstream forever, and the city became my second home,” she said. “I later focused on the situation in the Uyghur homeland (aka Xinjiang), to which I made a series of field trips, long- and short-term-, between 1995 and 2018.”

Dr Smith Finley said since taking up her post at Newcastle University in 2000, she has worked tirelessly to introduce students from the UK, Europe and beyond to the world of Chinese society and politics.

“I have prepared successive student cohorts for their immersion in Chinese culture, and have visited our students each year in situ across five Chinese cities,” she said.

“When China applies political sanctions to me, it thus stands to lose an erstwhile ally,” she said. “Since 2014, I have watched in horror the policy changes that led to an atmosphere of intimidation and terror across China’s peripheries, affecting first Tibet and Xinjiang, and now also Hong Kong and Inner Mongolia.”

“In Xinjiang, the situation has reached crisis point, with many scholars, activists and legal observers concluding that we are seeing the perpetration of crimes against humanity and the beginnings of a slow genocide. In such a context, I would lack academic and moral integrity were I not to share the audio-visual, observational and interview data I have obtained over the past three decades.”

“I have no regrets for speaking out, and I will not be silenced. I would like to give my deep thanks to my institution, Newcastle University, for its staunch support for my work and its ongoing commitment to academic freedom, social justice and inter-ethnic equality.”

Following the announcement of sanctions against Dr Smith Finley, more than 400 academics have written an open letter to The Times in support, asserting their commitment to academic freedom and calling on the Government and all UK universities to do likewise.

There are increasing demands from human rights activists to take action over China’s ‘soft genocide’ in Xinjiang. Tit-for-tat sanctions will not resolve the issue. That will take much firmer action from governments, organisations and individuals who are complicit in the subjugation of the Uyghurs, by buying Chinese products and accepting money built on their suffering.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”85″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Mar 21 | 50 years of Index, Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

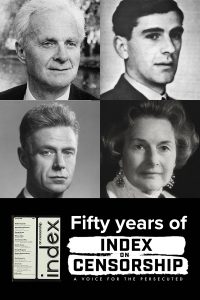

Clockwise from top left: Poet Stephen Spender, codebreaker and historian Peter Calvocoressi, biographer Elizabeth Longford (© National Portrait Gallery, London) and philosopher Stuart Hampshire (The British Academy)

The founding story of Index is such an emotive one, at least for me. A challenge was laid at the feet of some of the great and the good – a global call for solidarity with those thinkers and creative beings who were living under a repressive regime. Supporting those dissidents who were standing against totalitarianism. Providing hope, solidarity and most importantly a platform to publish their work, to tell their stories.

50 years ago this week, four extraordinary people signed our charitable deeds founding Index on Censorship – Stephen Spender, Elizabeth Longford, Stuart Hampshire and Peter Calvocoressi. Their vision was clear – we were to be a voice for the persecuted, providing a home for dissident writers, scholars and artists and to shine a light on the actions of repressive regimes. You can read more on our amazing founders here – www.indexoncensorship.org/50yearsofindex

I think we’ve lived up to their vision.

Over the last half century, with the help of so many, we’ve featured the works of inspirational dissident writers from Vaclav Havel to Salman Rushdie to Ma Jian. We’ve covered every aspect of censorship throughout the world from journalists being assassinated to governments restricting access to the internet. We’ve run successful campaigns on issues as varied as libel reform in the UK to hate speech. We’ve exhibited the work of artists and writers from repressive regimes at the Tate Modern and the British Library. And we’ve supported more than 80 Freedom of Expression award winners in the last 20 years – telling their stories and supporting their work.

There have been heartbreaking moments throughout our history, as friends were arrested for demanding their rights to free speech, as protesters were gunned down by repressive regimes, as democratic countries became more authoritarian and people because increasingly silenced. Our hearts bled, but our determination to be their voice, to fight with them and for them became stronger and stronger.

Birthdays provide a moment for reflection. By their very nature, you explore the past – what went well, what didn’t? What should we be doing in the years ahead, what should we be focusing on. On our 50th birthday, what is clear is that our work is not done. That too many people are still being silenced, so we will keep fighting the good fight.

Because of the impact of Covid-19 we aren’t going to get to have a big birthday party this month (although I’m adamant we will to celebrate 50 years of the magazine next year), but we won’t let our 50th birthday go unmarked either

You’ll have seen our new branding for Index. Next month we’ll have a new design for the magazine, which I hope you’ll love – the team have done an amazing job. We have lots of plans for the months ahead – and I hope that you’ll be with us for the fights ahead.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Mar 21 | 50 years of Index

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116457″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Of the “gang of four” who signed the documents establishing the Writers and Scholars Education Trust fifty years ago on 25 March 1971, Peter Calvocoressi perhaps embodied the spirit of that trust more than the other three. He was both writer and scholar. And many things besides.

In 1968, Calvocoressi published what became the definitive work on post-war global history, World Politics Since 1945. The book, which the Sunday Times called “masterly”, has remained in print ever since and stretches to almost 900 pages.

It is one of more than 20 books he wrote during his lifetime, which stretched from a Who’s Who in The Bible to Suez: Ten Years After.

His academic credentials were equally impressive: he was Reader in International Relations at the University of Sussex, a post created especially for him.

The Calvocoressi name hints at his most international of upbringings. He was born in Karachi, in what is now Pakistan, but then was British India, making him a British subject. However, in one of his autobiographical works he considered himself “entirely Greek”, being part of the Ralli family who left the Aegean island of Chios in the 19th century diaspora.

Peter’s parents moved to London in 1910 and he was born two years later. Peter was educated at Eton and Balliol College, Oxford where he got a first in modern history.

He was called to the Bar in 1935 and shortly thereafter was recruited into the Ministry of Economic Warfare, based at the London School of Economics.

Soon after the start of the Second World War, Calvocoressi resolved to volunteer to become more active in the war effort. After a day of tests at the War Office he was told he was “no good, not even for intelligence”.

That conclusion proved to be very wrong. Soon after, through a contact, he was interviewed by the Air Ministry and shortly after became an RAF intelligence officer. In 1942, his gift for languages saw him plucked out for duty to Bletchley Park, the wartime home of the Allied codebreakers.

There he worked in the famous Hut 3, which decrypted messages from Germany’s Enigma machines and passed intelligence, known as Ultra, to the Allies’ military commanders. His time at Bletchley, where he went on to lead Hut 3, is described in his revelatory book Top Secret Ultra, published in 1980, shortly after the activities of the Allied codebreakers were first made public.

After the war, Calvocoressi was asked to participate in the Nuremberg Trials, helping obtain evidence for the Allied prosecution team and in which he cross-examined former German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt.

Calvocoressi spent much of the Fifties researching and writing his Survey of International Affairs series, revealing his firm grasp of global politics and international relations.

He was asked to join the council of the International Institute for Strategic Studies in 1961 and later was instrumental in the early years of Amnesty International.

In 1967, he was called on as an independent expert to find out whether Amnesty had been infiltrated by British intelligence agents – his investigation proved that it had not. He steadied the ship at the organisation and served on its board from 1969 to 1971.

Throughout the decade, Calvocoressi was a member of the UN’s Commission on discrimination and the protection of minorities and became a member and chairman of the Africa Bureau, which lobbied against apartheid, at the request of his friend David Astor, owner and editor of The Observer.

Calvocoressi’s international experience and erudition made him an obvious choice to be asked to help found the Writers and Scholars Educational Trust, the organisation that is today better known by its working name of Index on Censorship.

Calvocoressi contributed to Index’s work in the early years but the world of publishing came calling.

He became a partner in publishers Chatto & Windus and Hogarth Press and was later asked to be chief executive of Penguin Books, a position he held until 1976. He continued his prodigious writing output throughout the Eighties and Nineties.

He had strong freedom of expression values too. He believed in the freedom to publish – writing a book of the same name which Index published in 1980.

He also believed in the freedom of the press but not at any cost.

In the case of the Pentagon Papers, the revelations around US involvement in the Vietnam War, he wrote to the Sunday Times about the decision of US newspaper editors to publish them.

He wrote: “The newspapers maintained that they were entitled to print the Pentagon Papers because the documents had come into their possession and they themselves judged that publication could not harm national security.

“But is an editor in a position to judge this? Surely not, for he cannot know enough of the background to tell whether he is giving something away.”

“Governments must have secrets whether we like it or not, and the power to preserve them. I am not denying that our own government overdoes the secrecy, sometimes absurdly so.”

What readers of that letter did not know, of course, was Calvocoressi’s personal involvement in the biggest secret of the war: the codebreaking at Bletchley Park.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Mar 21 | 50 years of Index

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116444″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Philosopher Stuart Hampshire knew evil was real. He had seen it, written about it and, perhaps, it had driven him to do something about it.

He was 25 by the time the Second World War broke out and he spent his formative years in a position in military intelligence.

His job was to interrogate, and it was this that brought him face to face with Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the high-ranking Austrian SS officer who was a key figure in the Holocaust.

Nancy Cartwright, Hampshire’s second wife and fellow philosopher, told Index, “He interviewed, as a young man, Ernst Kaltenbrunner. I think that had a real effect.”

Cartwright suggested that much of Stuart Hampshire’s personality reflected the work he was passionate about and he surrounded himself with revered thinkers and writers, including his closest friend, the political theorist Isaiah Berlin.

He was well-liked by his peers and was deemed to be warm-hearted and polite. Or, as Cartwright fondly describes him, “terribly English”.

As Cartwright remembered, he would sometimes sit in restaurants with Nancy and their two daughters and make up stories about the people sitting next to them, imagining who they were and what they were about in detail.

Stories, clearly, were important to him and people and the challenges they faced were significant too.

“I think he had a vivid sense of what it was like to be someone else. He could think of himself as being someone else,” said Emma Rothschild, the economic historian and Hampshire’s goddaughter – although this was never formalised at a font.

Hampshire was seen as a “cautious, honest and meticulous thinker” according to the philosopher Jane O’Grady, writing his obituary in The Guardian.

Free speech ranked highly among his values.

Cartwright said: “He had a sense that there is real evil and it needs to be combated. I think that was relevant to his work on Index. He was as much concerned about the people being censored and what was happening to them as he was about the issue in general.”

Hampshire, author of the acclaimed book Thought and Action, was a keen supporter of the post-war Labour government but never referred to it as such, instead preferring to say “the good Mr Attlee”.

“He always was distressed at inequality and poverty,” said Cartwright and he welcomed the wealth of social changes that Attlee oversaw: the foundation of the National Health Service and the expansion of the welfare state.

Hampshire also played a role in the implementation of the Marshall Plan, the financial rebuilding of Europe after the Second World War.

After the war, he became a senior research fellow at New College, Oxford before taking a domestic bursarship at his alma mater of All Souls. He later joined Princeton in its Department of Philosophy.

By the time the idea for the Writers and Scholars Education Trust, and Index, was being discussed, he had returned to Oxford as warden of Wadham College. Backing the idea of the trust and Index was natural to him.

“He was so keen on Index and it doing important things,” said Cartwright.

Emma Rothschild said his character was well-suited to setting up a free speech magazine.

“He was extremely involved with and excited about starting Index and I remember vividly seeing the first issues. It was one of his important steps into public life. He had been very involved in the great world of politics and international relations during and after the Second World War and then had been a bit more remote from it,” she said.

“I think Index was his way of moving back into large public questions. It was something he was extremely excited about and at the same time he found thinking about public life very stimulating for his philosophical writing.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Mar 21 | 50 years of Index

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116450″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Elizabeth Longford’s involvement as one of the founders of Index on Censorship should come as no surprise. By the time she signed the deeds of the charity she was established as a prominent newspaper columnist and biographer and had become a regular on the radio programme Any Questions as what would now be called a celebrity pundit. Driven by a socialism forged in the Depression and her deep Catholic faith, she had an unswerving instinct for defending the underdog, despite her privileged background and her later fame as a royal biographer.

She was born Elizabeth Harman into a family of doctors and spent a comfortable childhood in Harley Street, London. At Oxford she was part of a gilded generation of intellectuals that included philosopher Isaiah Berlin, Hugh Gaitskell, who later became leader of the Labour Party, and poet Stephen Spender, her co-founder at Index. It was at Oxford too that she met her husband Frank Pakenham, later Lord Longford, describing him as “like a Greek God”.

After university, she went to work for the Workers’ Educational Trust in Stoke, where her socialism took root. She later said: “Stoke became as much a part of me in 1931 as Oxford had been for the past four years. The working-class ethos had become my own”.

When her husband took a post as a politics lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford, Elizabeth joined the local Labour Party and stood, unsuccessfully, as a candidate in Cheltenham in 1935. She admitted to an “addiction to motherhood”, but after bearing the last of her eight children, she again stood as a Labour candidate in 1950, this time in Oxford, but never did become an MP.

She had become a Catholic in 1946, following the earlier conversion of her husband. Her daughter, the historian Antonia Fraser, told Index Elizabeth was particularly affected by the treatment of the Catholic Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty by the Communist authorities in Hungary. Mindszenty was a vocal opponent of Communism, who was the subject of a show trial in 1949. He was released from prison during the Hungarian uprising of 1956, but after the Soviet invasion crushed the revolution he was forced to flee to the American embassy in Budapest, where he lived until 1971. He was finally allowed to leave Hungary for exile in Vienna around the time that Index was founded.

Elizabeth’s career as writer began in the 1950s, when she was invited by Lord Beaverbrook to write a column on the Sunday Express. She later also wrote for the News of the World and the Sunday Times, usually on domestic subjects such as parenthood.

She was in her fifties when she turned to historical biography. Her first bestseller was Victoria RI, published in 1964 and she went on to write an acclaimed two-volume life of Wellington and works on Churchill, eminent Victorian women, Byron and the house of Windsor. She was the biographer of both the Queen and the Queen Mother.

She wrote her autobiography, The Pebbled Shore, to mark her 80th birthday in 1986 but did not stop there. Royal Throne, published in 1993, designed as a reflection on the future of the royal family coincided with the Queen’s “annus horribilis” when Charles and Diana separated. She remained, in later life, a staunch supporter of the monarchy.

Elizabeth Longford sat at the head of a dynasty of writers: her son Thomas Pakenham, daughters Antonia Fraser, Rachel Billington and Judith Kazantzis and granddaughters Eliza Packenham, Flora Fraser, Rebeca Fraser and Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni.

The one great tragedy of Elizabeth’s life was the loss of her daughter, Catherine Pakenham, in a car crash in 1969. The Catherine Pakenham prize for young women journalists was established in her memory.

Her own legacy is marked by the Elizabeth Longford Prize for Historical Biography.

But her legacy is also Index on Censorship, which continues to fight for the principles of freedom of expression and liberty of thought which she held so dear.

Flora Fraser, chair of the Elizabeth Longford Prize for Historical Biography, writes: “My grandmother believed passionately in the mission of Index on Censorship to highlight the work of fellow writers and scholars, wherever in the world they faced obstacles to freedom of expression.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Mar 21 | 50 years of Index

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”97164″ img_size=”800″][vc_column_text]Stephen Spender (1909-1995) was a British poet, essayist and human rights advocate. He was born in London to journalist Harold Spender and the painter and poet Violet Hilda Schuster.

Spender studied at University College, Oxford but emerged without a degree. He spent his time writing poetry, along with the likes of W H Auden and Cecil Day Lewis, and his poems touched upon the most pressing social and political issues of the age.

Spender’s role in establishing Writers and Scholars International, and subsequently Index on Censorship, is inextricably bound with that of dissidence in the Soviet Union.

On the 12 January 1968, western radio stations broadcast an open letter, addressed to the ‘world public,’ from the Soviet dissidents Larisa Bogoraz and Pavel Litvinov. The letter had been written to draw attention to the so-called “Trial of Four” conducted by the Soviet authorities against the writers Ginzburg, Galanskov, Dobrovolsky and Lahkova for their involvement in samizdat, the secret copying and distribution of censored writing.

The following day Spender read the letter in The Times. Immediately moved by the appeal, and its elucidation on the legal persecution of writers in the USSR, he called upon a number of his friends, including Auden, philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell and composer Igor Stravinsky, to draft a response to express their support.

Although Spender’s telegram didn’t reach Litvinov or Bogoraz directly, Litvinov heard the message through a radio broadcast, and subsequently used the transnational samizdat smuggling networks to express his gratitude.

On 8 August, two weeks before the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Litvinov wrote to Spender. In it he outlined a proposition: the creation in England of an organisation that would be devoted to defending free expression, wherever its repression may occur.

With the help of the philosopher Stuart Hampshire, Spender created a committee, Writers and Scholars International, made up of a number of prominent academics, journalists and writers.

It was this that led to the creation of Index on Censorship magazine, with the translator Michael Scammel, as Editor-in-Chief. The magazine was to function in accordance with Litvinov’s suggestions; it would be dedicated to creating an ‘Index’ on those, in whatever country they may be, who find their free speech to be stifled.

Throughout his life, Spender was steadfast in his concern for the principles of free expression, and of social inequality. He spent a brief spell, “a few weeks”, according to his 1949 essay in The God That Failed, with the British Communist party in 1936. Spender described both his enrolment in the Communist Party and his leaving it as being both inextricably linked with the Spanish Civil War; the former in terms of joining the ranks in the fight against fascism, and the latter after witnessing the Red Terror of the Soviet-influenced Communists in Spain.

He maintained a consistent anti-Stalinist left position throughout his life, and remained concerned with the consequences of the “disease of capitalism”, as he put it, thus circumventing the frenzied bipolarity of the Cold War atmosphere to remain an ally of the voiceless and oppressed. When Ramparts revealed in 1966 that the CIA had been funding the Congress of Cultural Freedom, and thus their money had equally gone towards Spender’s own journal, Encounter, he quit the Congress in disgust. When the Litvinov-Bogoraz appeal appeared shortly after this scandal, it galvanised Spender into new action.

In the first issue of Index on Censorship magazine Spender wrote an essay entitled With Concern For Those Not Free in which he outlined why Index was so necessary:

“I think that doing this is not just an act of charity. It is a way of facilitating and extending an international consciousness, traversing political boundaries…censorship and acts of persecution. The world is moving in two directions: one is towards the narrowing of distances through travel, increasing interchange…the other is towards the shutting down of frontiers, the ever more jealous surveillance by governments and police of individual freedom. The opposites are fear and openness; and in being concerned with the situation of those who are deprived of their freedoms one is taking the side of openness.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Mar 21 | News and features, Slapps, Statements, Sweden

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Twenty-four organisations express their solidarity with the Swedish business and finance publication, Realtid, its editor, and the two journalists being sued for defamation in London. Realtid are due before the High Court tomorrow for a two-day remote hearing that will decide whether England and Wales is the appropriate jurisdiction for the case to be heard.

Twenty-four organisations express their solidarity with the Swedish business and finance publication, Realtid, its editor, and the two journalists being sued for defamation in London. Realtid are due before the High Court tomorrow for a two-day remote hearing that will decide whether England and Wales is the appropriate jurisdiction for the case to be heard.

Realtid is being sued by Swedish businessman, Svante Kumlin, and his group of companies Eco Energy World (EEW), for eight articles that they published last year. Realtid had been investigating EEW ahead of an impending stock market launch in Norway, a matter of clear public interest. Prior to publication, the journalists contacted Kumlin and EEW to request an interview and reply, but neither were provided. In November 2020, Kumlin and EEW filed a defamation lawsuit at the High Court in London against Realtid, its editor-in-chief, and the two reporters behind the investigations.

“We are concerned about the use of litigation tactics to intimidate journalists into silence,” five international freedom of expression and media freedom organisations wrote in a statement last December, which condemned the legal action and deemed it a strategic lawsuit against public participation (Slapp). Slapps are a form of vexatious legal action used to silence public watchdogs, including journalists.

The hearing is expected to conclude at lunchtime on Thursday 25 March, but the judgement that will decide whether England and Wales is an appropriate jurisdiction for the case to be heard is likely to be reserved for a later date. Although Realtid is a Swedish-language outlet based in Sweden and Kumlin is domiciled in Monaco, Kumlin and EEW claim to have “significant business interests” in England that, they claim, provide sufficient grounds for the case being brought in the UK.

Ahead of the hearing we, the undersigned organisations, express our solidarity with Realtid. We are extremely concerned that this Slapp appears to be an effort to discredit the journalists and force them to remove their investigative articles.

Signed:

Index on Censorship

ARTICLE 19

Civil Liberties Union for Europe (Liberties)

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

IFEX

International Press Institute

OBC Transeuropa

Reporters without borders (RSF)

National Union of Journalists in the UK and Ireland (NUJ)

Justice for Journalists Foundation

Swedish Union of Journalists

Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project

Mighty Earth

PEN International

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

English PEN

Swedish PEN

Blueprint for Free Speech

Protect

Media Defence

International Media Support

The Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation

Global Witness

Publicistklubben[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Twenty-four organisations express their solidarity with the Swedish business and finance publication, Realtid, its editor, and the two journalists being sued for defamation in London.

Twenty-four organisations express their solidarity with the Swedish business and finance publication, Realtid, its editor, and the two journalists being sued for defamation in London.