18 Oct 13 | About Index, Events, Volume 42.03 Autumn 2013

The following speech by Sarah Brown, education campaigner for A World at School, was delivered at the launch event for the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

I am delighted to be at Lilian Baylis Technology School – I went to school in North London, but my first flat was just down the road from here – I know how hard everyone at this school has worked for it become the first in Lambeth to get an outstanding in its Ofsted and now stands out as ‘outstanding in all aspects’ in the top 10% in the country. Being named for a pioneering woman who nurtured some amazing talent in the theatre, opera and ballet worlds leaving her mark across London gives the school a lot to live up to, but clearly nurturing some amazing talent here of its own these days.

Index on Censorship’s magazine that we are launching here tonight also serves to highlight some talented voices, and some very courageous ones too. Like all of the magazine editions which came before it, it is distinguished by both the quality of its writing and the bravery of its stance. But this one is particularly important to me for the priority it has placed on the voices of women. From pioneering feminists writing about women’s safety in India to the stories of female resistance and of hope from the Arab Spring, this magazine is giving a megaphone to the people whose contribution is so often marginalised, ignored, or eliminated altogether.

In the spirit of Index on Censorship’s core values, the power of our voice is the theme of my remarks tonight. And I want to start by updating a feminist slogan that lots of women who have done pioneering work on role models have been using for years now. Their view is ‘if she can see it, she can be it’. In other words, if you have a visible role model you are much more likely to keep fighting to get past all of the hurdles that are still too often put in the way of girls and women, just as they are for people who are disabled, or LGBT or BAME, or hold a forbidden political viewpoint in the harshest of regimes around the world.

‘If you can see it, you can be it’ – I very much think that’s true – the importance of strong visible women role models. Even my own sense of what is possible for me has certainly been determined by watching women – whether my own mother learning and leading throughout her life, from running an infant’s school in the 70’s in the middle of Africa, completing her PhD a few years go in her seventies and even now I am struggling to keep up her as she launches a new project leading the research on a study of quilt-makers (mostly women) and the stories they tell. Other role models from me have ranged from the icons of my teenage years from poet and rock artist Patti Smith to writer Jill Tweedie to American feminist Gloria Steinum. Today my work leads me to meet such a range of inspirational women leaders from Graca Machel to Aung San Suu KyI to President Joyce Banda of MalawI to young women like AshwinI Angadi, born blind in a poor rural community in India she fought for her education, graduated from Bangalore university with outstanding grades, gave up her job in IT to campaign for the rights of people with disabilities, and I find myself alongside at the UN last month.

So I agree that visibility counts, but if I think of my role models they are all women who never give up raising their voices – who make a career literally of speaking up. And I want to update that old slogan with a rather more disturbing thought and suggest tonight that if you can hear her, you will fear her.

Let me explain what I mean.

From Nigeria to Egypt to Yemen and Afghanistan to the richest countries of the West, we are seeing the rise of targeted attacks focused on women who use their voice to speak out for other women. Sometimes these attacks are physical, and I will talk about them more in a moment. But here in the UK there has been a spate of attacks which are verbal and online, and which are perpetrated by men who fear women’s power.

From the disgusting rape threats directed at Caroline Criado-Perez for daring to suggest a woman should remain on British bank notes to the horrendous and sexualised verbal violence meted out to Mary Beard after she appeared on question time to model Katie Piper finding her online voice speaking up for the stigma of disfiguration in a defiant response to the acid attack on her, and the creation of her defiant new beauty at the hands of her NHS surgeon. And of course, the all too prevalent victims of domestic violence who get a collective voice through women’s aid and the main refuges around the UK – who speak up more when they see it can even happen to a goddess like Nigella.

It is clear that the public square – and too often the private home – simply doesn’t provide a safe environment for Britain’s women.

If anybody doubts how bad things have got, I’d encourage you to go and take a look at Laura Bates’ work with the Everyday Sexism Project, an online directory of harassment, discrimination and abuse submitted by over 50,000 women who are shouting back. It paints a picture of a Britain in which violence and the threat of violence against women is so routine, women had almost ceased to notice it as a crime and an outrage, until a platform came along that gave their problem visibility and, with it, importance.

So I want to suggest that a public square which is so hostile to women that they do not feel they can participate in it without inviting overwhelming abuse is, itself, a form of censorship. It might not be the same process as smashing up a newspaper office or burning a book or even shooting teenage girls on a school bus, but the effect is the same: that of silencing a voice which has a right to be heard.

And if you want further evidence of how hearing how women’s voices can terrify those who risk losing their power, just consider how the worst misogynists in the world were afraid of just three words.

The words I’m talking about weren’t said by somebody famous. They weren’t said by somebody powerful. They hadn’t even been planned before they were uttered. But they awoke the world.

Malala YousafzaI as a schoolgirl from rural Pakistan published her youthful diary detailing how life had changed for girls after the Taliban took over her mountain town. She and her friends Shazia and Kainat spent the next few years campaigning for girls to be allowed to return to school, although they knew how dangerous speaking out against the Taliban could be. Malala even talked in interviews about how they might try to kill her for it.

Just over a year ago, this worst imagining happened and Malala was targeted by a Taliban assassin. He boarded the school bus, identified Malala and shot her in the head, and injured Shazia and Kainat sitting either side of her. As the footage of Malala’s airlift to safety was broadcast young women used just three words to claim their solidarity and support with her “I am Malala’. She and her two friends are all now safely in the UK continuing their education, and as the worlds’ gaze has given them some safety the campaign continues with a growing movement of young people all of whom are role models for every child around the world, whether in school or waiting for the dream to come true and the opportunity to learn coming to them too.

It was such a powerful reminder of a question I first asked myself some time ago:

Why is the most terrifying thing for the Taliban a girl with a book? Or for that matter the terrifying group in Nigeria – Boko Haram – who are firebombing schools and dormitories while students sleep. Boko Haram – the name literally means – western education is evil.

These terrorists know, better than we do, that a girl with an education is the most formidable force for freedom in the world. A girl who can read and write and argue can be brutalised and oppressed, she can be bought and sold, discriminated against and denied her rights. But she cannot, in the end, be stopped.

Girls like Malala, Kainat, Shazia and others in the end, will prevail.

And that is why they hate them so.

And so it seems to me if a girl like Malala, on her own, can inspire so much fear, then imagine what she could do if backed by a movement of hundreds of millions. That is why I believe that the efforts to achieve global education are at the heart of how we unlock the potential of every young citizen. As children learn, they achieve understanding, tolerance, opportunity and the chance to contribute to a better world. Reaching girls is at the heart of this – we need to do so much better for girls.

Right now, there are 57 million children missing from school. That’s 57 million of our younger selves missing out on the education which could transform not just their lives, but the world. 31 million are girls, and of those at school, many many millions are not learning, and girls are just not getting the same number of school years as their own brothers – to the detriment of everyone.

New research has shown that providing universal education in developing countries could lift their economic growth rates by up to 2% a year and the results are starkest of all when it comes to educating girls.

All the evidence shows that for every extra year of education you give a girl, you raise her children’s chances of living past five years old, because educated mums are more likely to immunise their kids and get them the health care they need. Educated girls are more likely to stay AIDS-free and are less vulnerable to sexual exploitation by adults. They marry later, have fewer children and are more likely to educate their children in turn. Perhaps most importantly of all, education increases a girl’s chance of well-paid employment in later life and the evidence suggests that female earners are more likely to spend their wages to the benefit of their children and community than traditional male heads of the household.

And the benefits, of course, don’t always stay just on a local community level, but can sometimes have national and even global implications too. Because if you look at women who have been in leading positions in every continent around the world – from Sonia GandhI to Graca Machel to Dilma Rousseff to Joyce Banda, they all have one thing in common. They all have an above average level of education. And that’s why one of my new mantras is women who lead, read.

If we want better politics, a politics of pluralism and freedom of expression around the world, then it begins with empowering women – and that begins with educating them.

So there are plenty of good reasons to invest in education and learning for every child – but the best bit is that we’ve already promised to. We are not advocating for a new pledge, simply for the fulfilment of one already made. In the year 2000 world leaders committed to getting every child in school by 2015 as part of a series of ambitious targets called the millennium development goals. World leaders have already signed the contract, now they just need to deliver the goods.

So for me the argument about whether we should invest in education to get the 57 children missing from school into the classroom is a bit of a no brainer – and for me there is no question that closing the gender gap in education should be the priority. As soon as people hear the facts, they tend to stop asking whether we should do it and start to focus on whether we can.

That’s a fair question and people will always want to probe whether we can make a difference to decisions taken hundreds of thousands of miles away. It’s a question I ask myself a lot too. But I take heart from two things. Firstly, we know that progress is possible even on seemingly very big problems because we have made it before. You can look at the big changes in the last century or so – from the end of slavery, achieving the vote for women, the end of apartheid – all started as impossible calls for change, but change came. Enough voices gathered together calling for the same thing – even a politician can’t fail to hear the call then, or if minded to change anyway can do so with a strong mandate behind him or her. Even campaigns I have contributed- that we may all have contribute to – from drop the debt to make poverty history to the maternal mortality campaign brought big changes – but I have heard first-hand what happens at the start – “it is too big an ask, it can’t be done in the time, it is too costly” – well enough free voices calling for action and – give it a little bit of time and a whole lot of noise – change comes. Less than ten years ago over 500,000 women were dying in pregnancy and childbirth unwitnessed, unacknowledged unnoticed by political leaders who held the power to save these lives. Today thanks to the collective voices of those who cared enough – through the white ribbon alliance and others, that number is a whopping 47% lower, and the work to reduce it further continues at the highest levels, and out in the more remote rural areas where the message needs to be carried far and wide to reach every woman at risk.

A 47% drop in the number of mothers dying. That’s not just a number – that means there are thousands of dads living with the love of their lives when they would otherwise have a broken heart nobody else could possibly mend. Thousands of big brothers and sisters who didn’t need to fear that in gaining a new member of the family they risked losing an old one. And thousands of babies being nursed to sleep tonight by the person who loves them most in the world and who has survived to love them as they grow. So this stuff works: campaigning is the key for all of us lucky enough to use our voices.

And on education, I am hopeful we can get even further than we have with the maternal mortality campaign, and achieve all of our goals by 2015. I know that sounds incredibly ambitious – because it means getting 57 million children into school in less than two years. Gordon and I have decided to devote the next years of our lives to this and we intend to be judged by our results. Increasing awareness is great – but if the numbers of children getting a high quality education does not increase in leaps and bounds in the years to come then we collectively will have failed.

Thankfully, we have a lot of help. When Gordon was appointed the United Nations’ Secretary General’s Special Envoy on education, the weight of the UN system was added to our cause. Business leaders have come on board to the Global Business Coalition for Education that I am fortunate to chair, and I am pleased that religious leaders have agreed to form a faith coalition to mobilise the faith communities as has happened so powerfully for debt relief and make poverty history in the past. Most significantly, younger people are lining up at as ambassadors, spokespersons, online champions and community mobilisers – the 600 strong youth leaders from the digital platform A World at School who assembled at the un on Malala Day in July, are all now engaging with their networks, supported by NGOs from around the world. The digital platform is growing rapidly, and the consistent messages, the constant call for action and the rising volume are starting to make a difference. From Syrian refugee children needing a place at school this autumn to young girls wanting to study before they marry in Yemen, Nigeria, Bangladesh to child workers who have never been inside a classroom, the momentum for them is growing.

This grand confluence of forces is powered by the single most important driver of change – every individual who cares enough to take up an action – whether just a tweet or post, or more. It includes you.

Because if we can’t mobilise millions of so-called ordinary people to do hundreds of extraordinary things, the governments of the world will conclude that the pledge they made to get every child into school can be allowed to quietly slip away, the pledge for gender equality ignored, the pledge that every child can be safe from violence, from trafficking and from finding their own voice just disappears. That would be a tragedy not just for the millions of children whose lives continue to be destroyed, but for the notion of progress itself.

If we can’t even rely on our leaders to do that which they have promised to do, can we rely on them to do all that we need them to do? I don’t want my children to grow up in a generation of cynics, a whole group of people who think that promises don’t get kept and politics doesn’t really work. I want them to see and to know that if we make a promise – particularly a promise to a child – we keep it. That when we see an injustice, we right it. That when we are presented with an opportunity we seize it. And that when we have the chance to change the world there is nothing we won’t do to see that potential fulfilled.

That, for me, is the ambitious spirit of activism which Index on Censorship embodies, and the one which we must now bring to bear in ensuring that the girls and women of the world learn first how to read, and then how to lead. This is the chance of our generation and I hope you, like me, think it is one we must grasp with both hands.

This speech transcript was originally posted on 18 Oct, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

18 Oct 13 | Bulgaria, Digital Freedom, Germany, News and features, United States

On 30 September, Bulgarian-German author Ilija Trojanow was travelling from Brazil to the US for a conference on German literature. That was his plan, anyway. At the airport in Salvador da Bahia, he was told his entry to the US had been denied. No explanation was provided then, and none has been provided since.

On 30 September, Bulgarian-German author Ilija Trojanow was travelling from Brazil to the US for a conference on German literature. That was his plan, anyway. At the airport in Salvador da Bahia, he was told his entry to the US had been denied. No explanation was provided then, and none has been provided since.

Trojanow is one of the main forces behind a 74,000 strong and growing petition against mass surveillance. Initiated and signed by some Germany’s biggest writers, the petition argues the government is bound by the constitution to protect its citizens against foreign spying.

His experience in Brazil exploded in the German media, but Trojanow seems more bemused than anything else.

“It wasn’t bad enough that governments are spying on everybody!” he says with a laugh. “What this shows is that general attacks on everybody and not individual victims, are too abstract. An individual case, even if it’s a minor one, can get more attention.”

While the incident did create more discussion around mass surveillance and caused a spike in the number of signatures, there is no doubt the petition already had widespread support. The issue of mass surveillance seems to have struck a particular chord in Germany. Trojanow believes this is due to their history.

“East Germany more than any other country in the former Soviet block has discussed its secret service files. It has been a dominant issue in the media. The archives are easy to access. Germans know how horrendous it is when the secret service is not under real control.”

He also thinks the famous German efficiency shines through even in this case. Many felt that something needed to be done about the mass surveillance, and when Germans set out to do something, they do it properly.

“It is quite ironic,” he adds: “Germans had democracy beaten into them. They were educated in democracy by the US and the UK. It seems they were good students!”

Trojanov himself has long been interested in the issue of state surveillance, with his 2009 book “Freedom Under Attack”, for instance, becoming a bestseller in Germany. For him, the issue carries a more personal dimension. Growing up in a Bulgaria, parts of his family were engaged in the struggle against the communist authorities.

“I am in the situation now where I am able to read transcripts of what adults in my family were saying, as our apartment was bugged.”

“What you realise is that when you have the attention of the secret service pointed at you, whatever you do is in some way proof of guilt. Even completely innocent things become potentially implicating.”

The petition was formally presented to the German government on 18 September, back when when it had 63,000 signatures. A month and ten thousand additional names later, they have still have yet to receive any sort of official reply. Still open, Trojanow and his compatriots now plan to take it global. As he says, mass surveillance is a worldwide challenge and cannot be tackled simply by and within one nation.

“I don’t understand why we wait until situation is completely unbearable. You start safeguarding your freedoms when they are attacked on the edges.”

This article was originally posted on 18 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Oct 13 | About Index, United Kingdom

Sarah Brown and Charley-Kai John (Photo: Andrei Aliaksandrau/Index on Censorship)

Sarah Brown congratulated the winner of the first Index on Censorship student blogging competition on Tuesday after meeting at the launch of the autumn issue of the Index on Censorship magazine.

Charley-Kai John was invited to the event at Lilian Baylis Technology School in London where Brown spoke on the right for girls to have access to education.

The pair spent time discussing John’s plans for the future and his interests in freedom of expression.

The invite was part of the competition prize which also saw John’s blog, a look at internet access in North Korea, published in the magazine and online, as well as a yearly subscription to the magazine.

John is in his second year at the University of Warwick where he is studying English literature. He is also a keen cartoonist and creates images for The Boar, Warwick University’s online news publication, and The Student Journals. Entrants to the competition were asked to write about the biggest challenges to free expression in the world today.

16 Oct 13 | Events, News and features, Volume 42.03 Autumn 2013

World leaders need to deliver on their pledges to institute universal primary education — especially for girls — if the world wants to empower the next generation, campaigner Sarah Brown said in a speech at the launch of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine on Tuesday.

“The women who lead, read,” Brown said. “A girl with an education is the most terrifying force in the world.”

The campaigner argued passionately for education being a key, vital factor in advancement of women and girls around the world. Brown cited statistics that underlined her point: Educated girls grow into women who are more likely to educate their own children, have them vaccinated and have jobs that support a better financial life for their families.

“Why is the most terrifying thing for the Taliban a girl with a book?” she asked when talking about the role of Malala Yousafzai, the teenager who was targeted for campaigning for girls’ education. Brown is co-founder of A World At School, the campaigning education organisation that helped convene Malala Day at the United Nations this summer.

Speaking at the Lilian Baylis Technology School in London, where she also met with students, Brown followed up the speech with a question and answer session, chaired by Helen Lewis, deputy editor of New Statesman magazine.

“I don’t understand why there is so much anger at women who speak out,” Brown said when Lewis asked about Twitter trolls.

Referencing the vicious Twitter attacks on Caroline Criado-Perez, she remarked: “It’s clear that the public square does not offer a safe space for Britain’s women.”

But she also spoke on the positive sides of online speech, saying Twitter can be a “space to describe yourself as you want to be described.”

Brown conceded there is still a lot of work to be done to reach universal education. With two years left to reach the Millennium Development Goal of universal primary education, millions of children around the world still don’t have access to it.

Brown said it was appropriate for her to speak at the launch of the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, which includes a special report on ignored, suppressed and censored voices.

• Full text/video of Sarah Brown’s speech

This article was originally posted on 16 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Oct 13 | Belarus, European Union, News and features

An old Belarusian joke suggests a simple way of improving one’s life. If you feel unhappy, just allow a goat in your house, live with it for some time, and then take the goat away. In principle, nothing changes – but you feel real relief and happiness! This is exactly the way the foreign policy of Belarus operates.

Close the Swedish embassy in Minsk, and then allow its re-opening. Arrest Vladislav Baumgertner, the CEO of the Russian potash giant Uralkaliy, and then set him free. In principle nothing changed, but each story ended with something like “an improvement in the situation” – or at least with an impression of such.

Last year EU-Belarus relations, already on the rocks, were further damaged by the infamous teddy-bear parachuting and subsequent diplomatic scandal with Sweden. In comparison with that period of “cold war” 2013 looks relatively moderate. For instance, the Belarusian foreign minister Uladzimir Makey was temporarily dropped from the EU travel ban list. Nonetheless, the overall temperature of relations is frosty.

Political prisoners remain jail in Belarus. The fact two of them were released recently had nothing to do with the authorities’ good will; it happened just because their prison terms expired. The decision to suspend the travel ban for Makey was also purely technical. The position of Foreign Minister from the very beginning wasn’t on the EU travel ban list in order to leave a channel for direct communication with Belarusian authorities. Makey, personally, is still on the black list and will not be allowed to enter the EU if he leaves his minister position.

NGOs and opposition excluded from talks?

Since the beginning of 2013 the number of contacts between the EU and the Belarusian Foreign Ministry has increased. EU diplomats call this process “consultations with the Belarusian government”. But it’s hard to say exactly what the content of these consultations is. It is known that the Belarusian side propose to re-organise the European Dialogue on Modernisation. This EU initiative would establish intergovernmental relations between the European Commission and the Belarusian authorities, including an annual meeting of presidents Lukashenka and Barroso. But they have also suggested excluding representatives of civil society and political opposition from the Dialogue.

According to Belarusian authorities’ rhetoric, any relations with the EU within the framework of the Dialogue on Modernisation or the Eastern Partnership should be built “on equal basis and should focus on mutually beneficial projects.” In translation from diplomatic to real language this is nothing but a request to lift all the conditions related to democracy, rule of law and human rights, and simply invest in Belarus’ economic and infrastructure development.

It comes as no surprise that the EU is not ready to fully support these proposals right now. That they’re ready to talk about it, however, does. The next phase of the European Dialogue on Modernisation is going to be limited to experts with a focus on the themes that only the Belarusian government is interested in. In fact, civil society has not been granted the status of full participants in the Dialogue – despite numerous statements and appeals about the vital necessity of this.

Opposition fractured, weakened and ineffectual

In 2014, the European Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS) will change their staff, so they should be interested in showing some progress with regards to Belarus. In the absence of real progress, renewal of official contacts with the Belarusian authorities could be presented as an achievement.

It is not worth blaming the EU for such behaviour, though, all the while Belarusians themselves have not done much to change the situation. Neither autocrats or democrats have undertaken significant steps to resolve the current deadlock. The latter manage to disunite – without ever forming a real unity in the first place. Political opposition was formally divided into two parts; the “People’s Referendum” campaign and the “For free and fair elections” coalition. Real differences between the two are hard to explain. Both of them pray to the old God of “communication with ordinary people”. This is a noble task in any sense, but actions proposed are not significantly different from previous unsuccessful attempts to respond to the people’s needs. The oppositions’ slogans are not easy to understand even for their closest civil society allies. Sometimes it feels like these activities are implemented just for the sake of keeping political activists busy, gaining some media attention and getting some resources from donors in the process.

The main aim for the opposition forces is to remain on the political scene until the next presidential elections. Independent civil society organisations are also divided in different camps and have lost their positive dynamics of previous years; still they have much more potential than the weakened political opposition. As a result of disunity among democrats they cannot respond properly to the EU proposals or the challenges of the internal political situation. The EU is listening to the contradictory voices of various Belarusian activists without the possibility to coordinate with them on the main course of action.

Challenges in encouraging change

Thus, the EU policy faces a clear choice: either to wait for internal changes in Belarus or try to actively facilitate them. The recommendations of the European Parliament on the EU policy towards Belarus (the so-called Paleckis’ report), adopted on 12 September 2013, make step in the latter direction. The central idea of strengthening pro-European attitudes among different groups of actors from the civil society to open-minded civil servants via closer engagement in cooperation with the EU looks good. Civil society is seen as one of the key actors in political dialogue with the EU. It is also mentioned that “the National Platform of the Civil Society Forum of the Eastern Partnership is an important and reliable partner and a unique communication channel to the Belarusian people for the EU”. Actions aiming at communicating European policies to the Belarusian citizens, expanding education programs, development of scientific cooperation are also recommended.

The European Parliament doesn’t propose significant changes in the current EU policy, but the EU needs to go much deeper into the Belarusian political situation to insure even these slight changes. The new way lies between facilitation of public dialogue between the Belarusian authorities and civil society on the one hand, and playing the engagement game with nomenklatura on the other hand.

This is not an easy task, it needs a lot of reflectivity, good understanding of the field, strong diplomacy and coordination between various actors’ – civil society organizations, political opposition forces, donor structures, EU member states, and international organizations like Council of Europe, OSCE, UN.

While playing this complicated game in some cases the EU will have to back one internal actor and its strategies against others. And this is what the EU is not ready to do. The overall approach demands to support all the actors who proclaim pro-democratic and pro-EU values. As a result the EU policy creates a plurality and centrifugal trends within the civil society and political opposition that is the main obstacle for consolidation among democrats. Attempts of strategic unification immediately run into charges of “monopolization” and “privatization” of civil society voice. The EU needs a strong internal counterpart in Belarus, which never appears without civil society consolidation, but it is not ready to let this consolidation happen. This vicious circle must be broken to proceed with the Belarus situation.

Of course, there is another way: impose travel ban on Minister Makey, then lift it – and, according to the famous “goat principle”, feel relief…

This article was originally published on 16 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

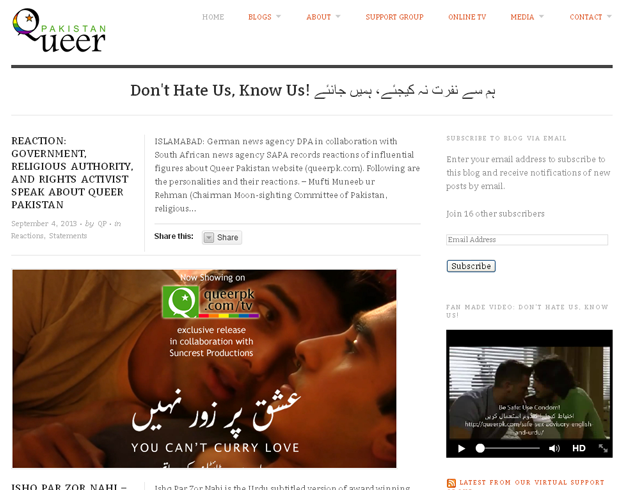

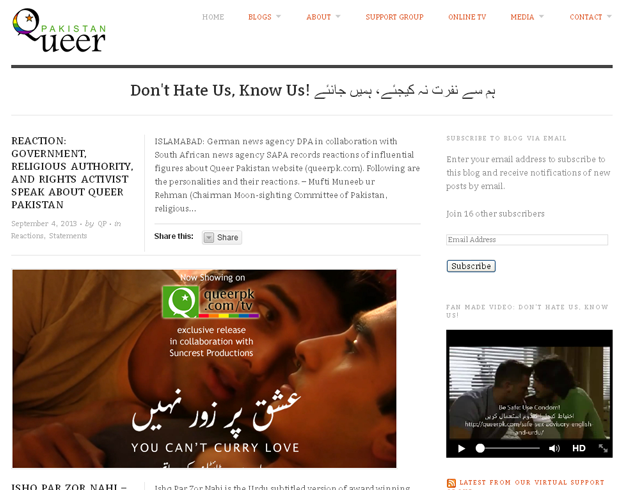

15 Oct 13 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Pakistan

Pakistan’s move to ban access to a gay website reflects the conservative society’s inability to accept a “larger world view”, activists say.

“Freedom of speech remains in peril and online privacy and security is almost nonexistent in the country making dissidents worry for their and their families’ safety”, Nighat Dad, a lawyer working with the Digital Rights Foundation in Pakistan, said.

Dad was referring to last month’s blocking of a gay website www.queerpk.com by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority for being “against Islam”.

But for others belonging to the LGBTQ community, the ban has not come as a big surprise.

“They banned YouTube, you think Queerpk would count at all?” said banker Imran, requesting only his first name to be used.

“It was quite expected and shows how immature this society is and how our government is keen on pandering to the idiocies of the worst among us”, said Ali (also preferring to use just his first name).

Kashif Khan, a gay university teacher, considers the website ban “just the tip of the iceberg” of a certain “mindset” that holds sway within the Pakistani society.

“We, as minorities, are not the only one affected by this heightened sense of self righteousness and religiosity which stems from this complete inability to entertain and appreciate any world view other than our own,” he said.

Further, he points out: “The closing of the mind and quashing of this spirit of inquiry is probably because a lot of beliefs that we have held sacred might not stand the test of rationality and empirical evidence.”

But Ali, for one, does not think it was a great idea for a group of LGBTQ community to try and create a space a space for themselves in public domain.

“Gay people here do not want a gay rights movement because this society isn’t the kind of society in which a gay rights movement can take place,” he said.

For too long, the LGBTQ community has remained invisible. They continue to enjoy both peace and relative freedom, but many fear that the moment they try to rock the boat and start demanding their rights, they may invite the attention of the religious extremist elements within society -much to their detriment.

Even the Pakistani law refuses to take a tolerant view of their existence. Article 377 of the Pakistan Penal Code prescribes up to 10 years in jail and a fine for those caught engaged in homosexual activity. Consenting sex between a man and a woman outside of marriage is criminalised and punishment awarded.

On the other hand, safeguarding citizens’ privacy is enshrined in Pakistan’s constitution, which calls “privacy rights” inviolable.

It is for that very reason Shahzad Ahmad, country director of Bytes For All, Pakistan, says that the Pakistani society “first acknowledge and recognise that the LGBTQ community exists”. It is also important, he said, to give more space to such portals where the gay community can discuss their issues in a “mature, understandable and engaging way”.

Even for Queerpk team the ban was not unexpected “given the backlash the website had received online and ‘reporting’ to PTA”. The team was prepared with a Plan B. “We mirrored the website onto a new domain, routing all traffic to the new website,” the website’s spokesperson (who didn’t want his name to be made public) wrote in an email exchange.

In addition, the website ban has not affected the netizens visiting the website in any way: “It hasn’t! If anything, it has brought together several thousand more users, hundreds of whom have written to us in appreciation and support, many of whom were not connected to any support online or offline. So for all reasons, the blockade has worked in our favour,” the spokesperson added.

When it comes to freedom of expression, Pakistan is not the most generous of countries. Freedom House’s annual report Freedom on the Net 2013 put Pakistan among the top ten countries where internet and digital media freedom is curbed.

“The recent ban of Pakistani gay websites is a clear sign that the new government is following what the past governments have been doing in Pakistan,” Dad said.

According to Ahmad the government’s “moral policing policy” curbs alternate and progressive discourse was the reason behind the blockade of Queerpk. This is not the first time that gay websites have been targeted, he explains: “I remember, another LGBTQ social networking website ManJam was banned in Pakistan and that ban still exists for Pakistani users.”

Currently there are over a dozen dating and social networking websites aimed at the Pakistani LGBTQ community. But the case of QueerpK is different, say experts, because it was more than a networking website. “Many important and relevant issues were being discussed on the website and an alternate discourse on sexual minorities’ rights was, for the first time, discussed in a very mature manner in a conservative society like Pakistan,” said Ahmad.

“With the government’s internet censorship policies over last few years it is quite evident that this new medium for communication for LGBTQ community won’t last long,” he added.

For that reason, BFA feels compelled to work with different international organisations in support of Queerpk to voice its concern against the ban. “We have also raised this issue at different forums and are also planning to raise it at the Internet Governance Forum,” Shahzad told Index.

This article was originally posted on 15 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Oct 13 | Magazine, Volume 42.03 Autumn 2013

[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”90659″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://shop.exacteditions.com/gb/index-on-censorship”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine on your Apple, Android or desktop device for just £17.99 a year. You’ll get access to the latest thought-provoking and award-winning issues of the magazine PLUS ten years of archived issues, including Not heard?.

Subscribe now.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Oct 13 | News and features, Syria

Paul Conroy at a protest in London last year calling for peace in Syria. Image Demotix/Russell Pollard

Journalists have a bigger influence on how war is perceived than in years gone by, said war photographer Paul Conroy at the Cheltenham Literature Festival yesterday.

Discussing how journalists and photographers cover wars and the pressures they are under, Conroy, who covered Syria with Sunday Times journalist Marie Colvin, said: “Everything is in the instant now, battles have been influenced by the immediacy of information.”

Conroy described how he and Colvin got into Syria using underground tunnels and the assistance of rebels. They were smuggled into Syria through a 3km scramble down a storm drain, which he described as “the only way”. He added: “The risks were quite high.”

He also talked about the attack on the media centre they were operating from, which killed Colvin. Conroy, who was badly injured, was rescued and got out of the war zone so he could be treated.

When asked about how newspapers’ tightening budgets were affecting foreign new coverage, Sunday Times associate editor Sean Ryan, who was chairing the event and was Conroy and Colvin’s desk contact, said: “We will always cover the biggest conflicts.” Conroy called for more funding for foreign news coverage from the media in general.

The acclaimed war photographer, who also covered the Balkan conflicts, said it was now impossible for journalists to switch from being with one side to covering the other side of a conflict. It had been possible in the 1990s, but this was no longer the case.

Because of this journalists had to be wary of how they might be used to put forward a biased or inaccurate picture. “What we realised was that you are open to be used for propaganda. What you have to do is double check and get eye witness accounts.”

14 Oct 13 | United Kingdom

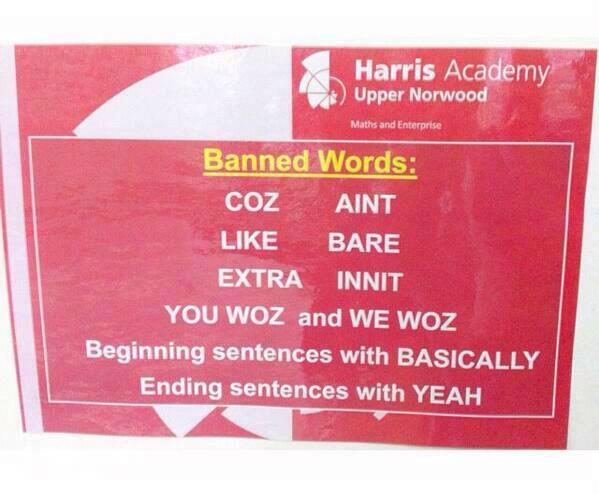

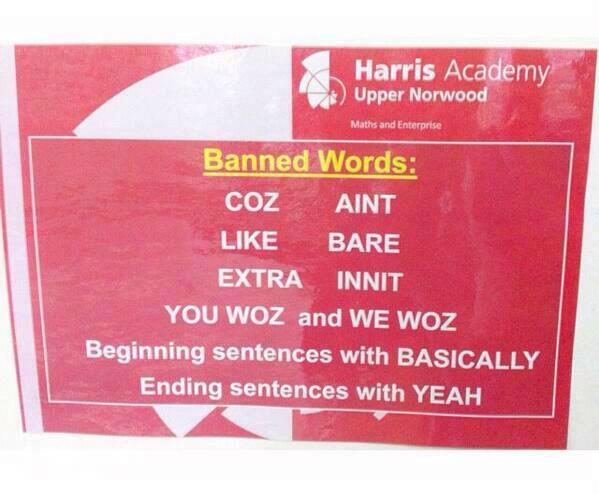

A London school has produced a list of phrases students are banned from using.

As opposed to Liverpool Football Club, who back in July issued their own list of “unacceptable words”, the Harris Academy in Upper Norwood doesn’t appear to be trying to tackle offensive language. Rather, they are standing up for Proper English, with banned words including “like’”, “bare” and “innit”.

It seems their desire to develop “articulate, perceptive and empathetic global citizens” is impeded by students beginning sentences with “basically”.

See the whole list below, via @_griff

This article was edited at 4:39 pm on 14 October 2013. The original version mistakenly linked and quoted the Harris Academy South Norwood website.

11 Oct 13 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society

Photo: Flickr user Secretary of Defense

A threat to press freedom is an assault on our right to know.

A new report from the Committee to Protect Journalists tries to capture the invisible impact of the Obama administration’s troubled relationship with the press. The report, authored by Leonard Downie Jr., former executive editor of the Washington Post, and CPJ’s Sara Rafsky, is the most comprehensive look at how the Obama administration’s actions have deeply damaged press freedom and the public’s access to information.

For those who have followed the administration’s policies, court cases and actions related to leaks and the press, the report doesn’t contain a lot of new information. What it does is weave together each of the cases and strategies the administration has pursued, surfacing key themes and illustrating that these examples are not aberrations, but part of a coordinated strategy. Presenting this bigger picture reframes the debate over press freedom in America and reminds us that it’s not enough to tinker around the edges; we need to demand a major course correction.

The report covers the administration’s leak investigations and policies, its surveillance programs, its secrecy and the use of its own media channels to evade “scrutiny by the press.”

All of this is punctuated by the interviews Downie conducted with journalists. Hearing from journalists in their own words, about the challenges they’ve faced and the concerns they have, brings home the seriousness of the crisis in press freedom.

New York Times National Security Reporter Scott Shane captured it best when he told Downie that sources are now “scared to death” to even talk about unclassified, everyday issues.

“There’s a gray zone between classified and unclassified information, and most sources were in that gray zone. Sources are now afraid to enter that gray zone,” Shane said. “It’s having a deterrent effect. If we consider aggressive press coverage of government activities being at the core of American democracy, this tips the balance heavily in favor of the government.”

That shifting balance of power is one of the critical takeaways from the CPJ report. Through efforts like NSA surveillance, the Justice Department’s seizure of phone and email records, and the “Insider Threat Program,” which encourages federal employees to monitor the behavior of their colleagues, the Obama administration has marshaled institutional resources toward efforts that erode press freedom and challenge newsgathering.

“The administration’s war on leaks and other efforts to control information are the most aggressive I’ve seen since the Nixon administration,” Downie writes. “The 30 experienced Washington journalists at a variety of news organizations whom I interviewed for this report could not remember any precedent.”

The report is an important addition to the debate about press freedom, but the scope of its inquiry is limiting. In focusing on the Obama administration, Downie examines in depth the various cases of journalists who have been caught up in federal investigations and the actions of federal agencies only.

As such, the report is not a full accounting of the state of press freedom today. A more comprehensive analysis of troubling state bills, worrisome court cases and the alarming spike in journalist arrests and harassment by local police would give a fuller picture.

In addition, the journalists implicated in the cases Downie reports on are all from mainstream media organizations like the Associated Press, Fox News and the New York Times, and most of his interviews are with Washington editors and reporters from major newsrooms. But the Obama administration’s adversarial relationship with the press has also impacted smaller newsrooms, freelance journalists, independent bloggers and citizen journalists.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has led the way in looking at the impact of threats to press freedom and freedom of expression on digital journalists and citizen reporters abroad. This report should be a starting place for the CPJ to assess the threats and challenges facing all kinds of journalists in the U.S.

It’s notable that, in its recommendations at the end of the report, CPJ calls on the Obama administration to “advocate for the broadest possible definition of ‘journalist’ or ‘journalism’ in any federal shield law.” The law, the CPJ says, must “protect the newsgathering process, rather than professional credentials, experience, or status, so that it cannot be used as a means of de facto government licensing.”

While the CPJ focuses here on the need for a shield law, this recommendation should apply to any law or guideline the administration implements. The shield law is important not only for how it defines a journalist but also for the precedent it could set for future press freedom decisions.

The CPJ also advocates for ensuring that journalists won’t be prosecuted for receiving or reporting on leaks, ending the use of the Espionage Act to prosecute those who leak information to the press, improving transparency about NSA surveillance, enforcing revised Justice Department guidelines, ending the use of overly broad secret subpoenas, and strengthening the administration’s adherence to the Freedom of Information Act.

It’s remarkable that we have to ask for these basic protections and reassurances from our government, but the CPJ report makes it clear that we can’t take press freedom for granted. This report should be a starting point for a much larger discussion that brings together journalists of all kinds, policymakers and everyday Americans to talk through the challenges, questions and concerns about press freedom.

We’re facing a fundamental and coordinated shift in how our government and press interact — and it’s not enough to respond to each attack in isolation. We need to launch a proactive effort to reassert the centrality of a free press in our democracy.

This article was originally published at FreePress.net and is republished here by permission.

10 Oct 13 | Digital Freedom, News and features

An alarming judgment has been issued by the European Court of Human Rights that could seriously affect online comment threads.

The judgment in the case Delfi AS v Estonia suggests that online portals are fully responsible for comments posted under stories, in apparent contradiction of the principle that portals are “mere conduits” for comment and cannot be held liable.

Further, the unanimous ruling suggests that if a commercial site allows anonymous comments, it is both “practical” and “reasonable” to hold the site responsible for content of the comments.

The ruling concerns a case against Estonian site Delfi.ee. In 2006, Delfi ran a story about a ferry operator’s changing of routes. This story lead to some heated debate in the comments thread, with, according to the judgment “highly offensive or threatening posts about the ferry operator and its owner”.

The owner sued in Estonia, and in 2008, a court found Delfi responsible for defamation. Delfi appealed on the grounds the the European eCommerce Directive suggested it should be regarded as a “passive and neutral” host. The case eventually ended up in Strasbourg.

Today’s ruling contains several alarming lines for anyone who runs a website with comments. For example, the court suggests that:

Given the nature of the article, the company should have expected offensive posts, and exercised an extra degree of caution so as to avoid being held liable for damage to an individual’s reputation.”

This is curious: any moderator will tell you that controversial comments can appear in the unlikeliest of places.

The judgment goes on:

The article’s webpage did state that the authors of comments would be liable for their content, and that threatening or insulting comments were not allowed. The webpage also automatically deleted posts that contained a series of vulgar words, and users could tell administrators about offensive comments by clicking a single button, which would then lead to the posts being removed. However, the warnings failed to prevent a large number of insulting comments from being made, and they were not removed in good time by the automatic-word filtering or by the notice-and-take-down notification system.”

This seems to suggest that Delfi’s attempts to make to filter vulgar content and remind commenters of their liability have actually been used against them. Even the reporting system is not enough for the court.

Perhaps most worryingly, the judgment delivers another severe blow to online anonymity:

However, the identity of the authors would have been extremely difficult to establish, as readers were allowed to make comments without registering their names. Therefore many of the posts were anonymous. Making Delfi legally responsible for the comments was therefore practical; but it was also reasonable, because the news portal received commercial benefit from comments being made.”

It is difficult to see how any site would allow anonymous comments if this ruling stands as precedent.

This would appear to be truly troubling judgment for website operators and moderators.

The ruling is not yet final and may be subject to further review.

This article was originally posted on 10 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Oct 13 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Azerbaijan Reports, Index Reports, News and features

Narimanov Park, Baku, 15 May 2010. Police forcibly detain a political activist during an unsanctioned protest. Photograph by Abbas Atilay

This report is also available in a PDF format.

As expected Azerbaijan’s autocratic president Ilham Aliyev was elected to a third term on 9 Oct.

This report addresses violations against freedom of expression on the eve of Azerbaijan’s presidential elections. It is based on field research conducted between 16 and 21 September 2013 in Baku. In 2012, international and national civil society groups denounced attempts by the Azerbaijani government to silence critical voices through fabricated charges, barring protests and blackmail. In 2013, the government has introduced a new set of repressive laws, curbs on media and arrests of journalists, political activists and human rights defenders.

Laws passed in May 2013 extend existing draconian penalties for criminal defamation and insult to online content and public demonstrations. Intimidation, harassment and violence against journalists continue with impunity. Civil society organisations have raised concerns about the deterioration of the media environment and the number of imprisoned journalists through the intensification of the practice of unjustified criminal prosecution.

It is important to note that country is due to assume the chairmanship of the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers in 2014, while it fails to comply with its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights.

IMPUNITY

Impunity for physical and moral attacks against journalists and activists continues unabated. There have been attacks on journalists during the period of the presidential elections. Those responsible for the murders of journalists Elmar Huseynov (2005) and Rafiq Tagi (2011) have yet to be found or tried. No suspects have been named or charged with the violent attack on Idrak Abbasov in 2012, weeks after he received an Index Award. Independent journalists receive threats and are subject to blackmail.

On a daily basis, journalists, who receive physical and psychological threats and make reports to the authorities, are denied justice or protection.

In September 2013, Index met with Ramin Deko, a journalist at Azadliq newspaper. In addition to regular intimidation and threats, Deko has been harassed financially, with prosecutions and fines obstructing his investigative journalism (see section on the economic squeeze on independent or critical media). Deko alleges he was abducted and beaten up on 3 and 4 April 2011 by law enforcement bodies. While he was illegally detained, he said he was told to stop critical articles and to change his workplace to a pro-government newspaper.[1] On 4 October 2013, Deko was part of a group of journalists attacked by a pro-government mob while covering a sanctioned opposition rally the central Azerbaijan town of Sabirabad. Tural Mustafayev, who was also among the journalists, said that they were assaulted, and their equipment was damaged by the mob while police officers stood by and made no effort to disperse the attackers. No measure has yet been taken to investigate the beating and harassment of the attacked journalists. On the contrary, the Interior Ministry released a statement justifying the action of the police and Bakunews internet television reporter, Ilham Rasulzadeh, was detained and taken to the Sabirabad police department.

Another journalist, Yafez Akramoghlu, told Index that the range of “tools” to intimidate journalists has widened. [2]

Akramoghlu is a journalist at Radio Liberty/Azadliq radiosu and correspondent for the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, which he calls “the North Korea of Azerbaijan”. Akramoghlu claims that in April 2013, his family received an envelope containing a CD and several photos. They depicted intimate pictures and a fake Facebook profile with fabricated Facebook chats between Akramoghlu and a woman (the same woman appearing in intimate positions in the photos). Shortly after receiving the envelope, Akramoghlu says he received a phone call from someone who identified himself as an employee of the Nakhchivan national security forces. This individual reportedly threatened to damage the journalist’s reputation by circulating the images if he did not stop his investigative work. Following his refusal to give in to blackmail, Akramoghlu claims he received assassination threats directed at himself and his family.

Investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova has also been the target of a smear campaign. On 7 March 2012, she received an envelope from an anonymous sender containing explicit photos of her and her boyfriend with a note warning her, “Whore, behave. Or you will be disgraced.” Ismayilova published the threat letter and continued her investigative work. On 14 March 2012, a secretly-recorded video of Ismayilova having sex with her boyfriend was posted on the internet. The previous day, a pro-government newspaper ran a long article attacking her and criticizing her personal life. In August 2013, 11 international NGOs sent a joint letter to President Ilham Aliyev and Prosecutor-General Zakir Garalov urging them to take concrete steps to ensure that the repeated harassment and intimidation of Khadiya Ismayilova is properly investigated. This was after Ismayilova sent at least four letters to the prosecutor’s office requesting updates on the investigation. According to Ismayilova, in its replies, the prosecutor’s office has merely stated that the investigation was ongoing, without giving any details.

Imprisoned journalists and activists also face intimidation and violence. In May 2013, one NIDA board member – Turgut Gambar – and two other youth activists – Abulfaz Gurbanli and Ilkin Rustemzade – were arrested on misdemeanour charges and had their heads were shaved while they served administrative detention.

Since his arrest in June 2012, Hilal Mammadov, editor-in-chief for Tolisho Sedo newspaper, has reported ill-treatment and torture. On Friday 27 September 2013, two weeks before the presidential elections, Mammadov was sentenced to five years in prison on charges of treason, inciting ethnic hatred and drug trafficking.

REPRESSIVE LEGISLATION

In the run up to the presidential elections, the framework for freedom of expression became tighter. Recent amendments to laws have further restricted freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and the work of civil society, by increasing sanctions for public order offences, including organising and participating in unauthorised demonstrations. Minor public-order offences now carry maximum jail sentences of 60 days, instead of 45. Adopted on 2 November 2012, new amendments to the law “On freedom of assembly” and to the Criminal Code saw fines for protesters who violate the law raised from 300 manat (USD 385) to 8,000 manat (USD 10,200) and introduced a prison sentence of two years. Criminalising the organisation and participation in peaceful protests has an increasingly chilling effect on freedom of expression in Azerbaijan.

Amendments to legislation regulating non-governmental organisations (NGOs), signed into law by the president on 11 March 2013, further stifle civil society in Azerbaijan, with NGOs now facing additional registration hurdles and stricter funding requirements. The new law bans cash donations above USD 200, and increased fines for non-compliance. In addition, NGOs that do not register under the law are unable to open or maintain bank accounts. This legislation further interferes with freedom of association already undermined in 2009 and 2011, after the introduction of overly complicated NGO registration requirements. The International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) identified a number of issues relating to NGO legislation in Azerbaijan, including the lack of transparency in the process of government authorities’ decision-making on whether to register an NGO. It is feared that the arbitrary application of the law directly undermines freedoms of expression and association. On 19 October 2011, the Council of Europe Venice Commission referred to NGO regulations in Azerbaijan as “a breach of international standards.”

In May 2013, the Azerbaijani Parliament adopted amendments to the Code of Administrative Offences, resulting in the extension of the permitted length of administrative detention. The maximum period of administrative detention sanctioning offences for “violation of the rules of organising and conducting rallies, demonstrations, processions, etc.” has been increased from 15 to 60 days.[3] This new legislation allows the arrest, for example, of people who distribute leaflets in the streets. On 19 September 2013, the police reportedly arrested and detained for a few hours 20 young people distributing leaflets for an authorised protest.[4]

In addition, Azerbaijan’s defamation legislation was extended on 3 June 2013 and now also applies to internet-based content and opinions expressed online, including in social media (see section on internet censorship). The new defamation law imposes hefty fines and prison sentences for anyone convicted of online slander or insults. This constituted a severe step back for Azerbaijani government that had committed to decriminalise defamation in its National Action Programme in 2011. In August 2013, a court prosecuted a former bank employee who had criticised the bank on Facebook. The court found him guilty of libel and sentenced him to 1-year public work, also withholding 20% of his monthly salary (see section in internet censorship).

MEDIA DIVERSITY, OWNERSHIP AND THE SQUEEZE ON THE OPPOSITION PRESS

The clampdown on independent and critical media continues, while nearly all broadcast media remain owned by the state or controlled by the authorities.[5] The independent press has faced economic discrimination, with editors claiming the authorities regularly pressure advertisers not to place ads in critical papers.[6] Meanwhile, Azerbaijani public officials have used criminal and civil defamation to stifle critical journalists.

Most of the nine national TV channels are either directly owned by the state or controlled by the authorities. The regulatory authority, Azerbaijan’s National Television and Radio Council – also charged with delivering broadcast licenses – is fully funded from the state budget and the president directly appoints all of its nine members. Journalists Index spoke to believe audiences are inundated with state propaganda, even through channels that offer no direct coverage of current events or political news.

Critical newspapers are barred from press distribution networks, which are controlled by state officials. Over 70 % of the distribution has fallen under government control and 42% of the population has no access to press kiosks with, on average, one retail stand for 11,250 inhabitants. Journalists and editors interviewed by Index expressed concerns over the election code that makes no provisions for balanced coverage of candidates and political parties in news and current affairs programs, including for public newspapers and broadcasters.

The first interim report of the OSCE/ODIHR Election Observation Mission reported that there were some concerns over the shortening of the official campaign period, which limits opposition candidates’ access to media and gives the incumbent president a disproportional advantage.

Along with the state’s control over the main media channels, the Azerbaijani regime keeps suppressing dissent or critical voices through defamation legal actions. According to Rashid Hajili from the Media Rights Institute, in the first six months of 2013, 36 defamation suits were brought against media outlets or journalists, four of which were criminal defamation suits. While courts have rejected all four criminal defamation suits, they have ordered media outlets and journalists to pay hefty fines in civil defamation cases. For example in June 2012, a court ordered Azadliq newspaper to pay 30,000 manat (USD 36,000) to the head of the Baku Metro Service, for an article published on 8 April 2012 about an increase in metro fares. In May 2012, a court fined Ramin Deko, investigative journalist at Azadliq, 3,000 manat (USD 3,800) for allegedly defaming Novruzali Aslanov, a pro-government member of parliament. Ramin Deko says: “Because of the fines, investigative journalism is at risk. There is an allergy to free expression in this country. In April 2011, I was abducted and beaten up, but defamation fines are equally chilling. It is another intimidation tactic and it interferes with my personal life.”[7]

INTERNET CENSORSHIP

Several activists have been arrested for their protest activities on social networks. In public statements, high-ranking officials aggressively attack social media, calling it a “harmful phenomenon.” Fazail Agamaly, an Azerbaijani MP, publicly called for access to social networking websites in Azerbaijan to be blocked during a speech in the country’s parliament, calling Facebook and social networks “a threat to Azerbaijan’s statehood.” The “war declared by the regime on social media” became more serious after street protests — organised by young people through Facebook — on 10 March 2013. On 16 March, president Ilham Aliyev allocated 5 million Azerbaijani manats (about USD 6.7 million) to fund activities of pro-government youth organisations on social networks. At the same time, seven members of the NIDA movement – a youth movement calling for more democracy in Azerbaijan – were arrested on charges of drug possession and inciting hatred. In May, the parliament adopted repressive legislation to extend criminal defamation laws to online content.

Rashid Hajili from the Media Rights Institute said: “Internet is growing and offers opportunities as well as challenges. The first steps toward prosecution for criminal defamation on Facebook last August [2013] are concerning.”[8] In August, Astara District Court convicted Mikail Talibov for sharing critical information on Facebook. Previously, Talibov worked at AccessBank, a bank with headquarters in Baku. Following his dismissal, he created a Facebook page where he harshly criticized the bank’s activity. The bank considered the Facebook page libelous and demanded the court to bring Talibov to justice for libel. The court considered the former bank employee guilty and charged him to 1-year public work, also withholding 20% of his monthly salary. The court also ruled Talibov to refute his criticism on Facebook. Many Azerbaijani civil organisations have condemned this ruling, with the Media Rights Institute calling it a “harsh punishment for expressions on internet forums”.

Defamation laws and monitoring of social media content are particularly chilling free expression online in Azerbaijan. Turgut Gambar, youth activist and member of NIDA, told Index that an increased number of young people refrain from expressing their opinion online due to the monitoring of social media and punishment of those who criticize the regime.[9] However, Gambar counts on the internet to empower the youth and complement traditional action for the democratisation of the country. “In March [2013], NIDA was able to mobilize and attract people who usually are not politicised thanks to social media”, says Gambar, “Internet is complementary to other forms of action such as graffiti, songs, or distribution of stickers”. The seven NIDA members arrested in March and April 2013 were particularly active on social media and known for their criticism of the authorities. The repression of free speech online is seen as an attempt to suppress activism on the last remaining haven for independent expression.

AZERBAIJAN AND THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE

In the run up to the elections, on 26 January 2013, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) failed to pass a resolution on political prisoners. The inaction of PACE has made Azerbaijan confident and since that failure at the PACE, Azerbaijan has felt emboldened to arrest more journalists and activists. On 1 October 2013, the Baku-based Human Rights Club released a new list of political prisoners counting 142 persons currently in detention or imprisoned for politically motivated reasons. The Human Rights Club notes that the number of politically motivated detentions and imprisonments has increased sharply since the defeat on 26 January 2013 of the key PACE resolution on “The follow-up to the issue of political prisoners in Azerbaijan.” At the time of the vote, there were 60 cases of alleged political prisoners included in then-rapporteur Christoph Strässer’s list.

It is of concern that the PACE has failed to hold Azerbaijan accountable for its Council of Europe obligations. According to interviewees, the resolution’s defeat has tarnished the Council of Europe’s credibility in Azerbaijan as an institution supposed to protect, promote and ensure human rights.

The government of Azerbaijan works particularly hard to influence opinion at the PACE, or to paralyse its action.[10] Christoph Strässer, a German PACE delegate who was the Special Rapporteur tasked with examining the situation of political prisoners in Azerbaijan, has been refused a visa to conduct a fact-finding mission to Azerbaijan. This refusal has angered German parliamentarians to the extent that the Bundestag’s Committee on Human Rights and Humanitarian Aid drafted a resolution demanding Strässer be granted a visa. Such is the influence of the government of Azerbaijan in Germany that the draft resolution was leaked to the country’s ambassador.

Azerbaijan pursues its lobbying at the Council of Europe (COE) and at national government level to persuade parliamentarians that the lack of a free media or its political prisoners are not worthy of special attention – or can be justified in the context of the ongoing Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. This distortion of the truth makes the work of human rights defenders all the more difficult, especially as space to express critical views in Azerbaijan has been gradually and progressively curtailed since Azerbaijan joined the COE in 2001. While Azerbaijan is preparing to assume the Chairmanship of the COE, it is of paramount importance for the Council of Europe to take tougher line against Azerbaijan’s crackdown on fundamental rights and freedoms.[11]

“In eight moths, Azerbaijan will run Europe’s official human rights organisation. The Council of Europe must take care about who speaks on its behalf. We are not saying that the council should prevent Azerbaijan from taking the chair, but it should take a tougher line vis-à-vis implementation of human rights commitments. If member states are allowed to get away with blatant violations and fail to comply with the Council of Europe rules and treaties, human rights become a dead letter”, says Emin Huseynov, Chair and CEO of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS).[12]

Recommendations

In the run-up to the 2013 presidential elections in Azerbaijan, the situation for freedom of expression has deteriorated. Index on Censorship makes the following recommendations:

– Ensure the immediate release of all persons imprisoned for exercising their right to freedom of expression

– Promptly investigate and prosecute all cases of violence, threats of violence, and blackmail against journalists, political activists and human rights defenders

– Respect and protect the right to freedom of expression offline and online, including by ceasing the practice of targeting social media users involved in organising protests

– Promote the development of public service broadcasting that is independent of government interests and acts in the public interest, with particular attention paid to the regions outside of Baku

– Cease the practice of pressuring and interfering with the work of NGOs, human rights defenders and lawyers

– Reform the law to protect the freedom of association

This report was originally published on 10 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Index on Censorship interview, Baku, 18 September 2013

[2] Index on Censorship interview, Baku, 18 September 2013

[3] Article 298.11 and 298.22 of the Administrative Offences Code

[4] Index on Censorship interview with a young political activist, Baku, 20 September 2013

[5] State control and the media in Running scared. Azerbaijan’s Silenced Voices, International Partnership Group for Azerbaijan report, 2012

[6] Index on Censorship interview with Rahim Ajiyev, acting editor-in-chief of Azadliq newspaper, Baku, 18 September 2013

[7] Index on Censorship interview, Baku, 18 September 2013

[8] Index on Censorship interview, Baku, 19 September 2013

[9] Index on Censorship interview, Baku, 20 September 2013

[10] Azerbaijan’s image problem, in Running Scared. Azerbaijan’s Silenced Voices, International Partnership Group for Azerbaijan report, 2012

[11] Azerbaijan will assume the chairmanship of the COE’s Committee of Ministers from July 2014

[12] Index on Censorship interview, Baku, 18 September 2013

On 30 September, Bulgarian-German author

On 30 September, Bulgarian-German author