30 Sep 13 | Digital Freedom, Guest Post, News and features, Pacific Standard

NSA operations center in 2012 (Photo: Public Domain)

A few days ago the European Parliament’s Office of Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs released a notably pointed briefing paper arguing for Europe to stop trusting American Internet services. The briefing and the committee are the latest forum tosuggest that European states create domestic cloud computing capacities to provide member states legal protection for NSA data surveillance. The report has the not-at-all-subtle title “The US National Security Agency Surveillance Programmes (PRISM) Foreign Intelligence Surveillance (FISA) Activities and Their Impact on EU Citizens’ Fundamental Rights.” Among the findings:

Prominent notices should be displayed by every US web site offering services in the EU to inform consent to collect data from EU citizens. The users should be made aware that the data may be subject to surveillance (under FISA 702) by the US government for any purpose which furthers US foreign policy.

The argument there being that people will have an incentive to find other websites to use. Particularly for e-commerce. Companies like Amazon, and U.S. airlines and ticketing agencies—Expedia and the like—won’t be pleased, and that in turn will create economic pressure to alter surveillance strategy, the report argues.

A consent requirement will raise EU citizen awareness and favour growth of services solely within EU jurisdiction. This will thus have economic impact on US business and increase pressure on the US government to reach a settlement.

That isn’t all. The report argues for the European Union to simply swear off U.S.-based cloud computing, and to develop local capacity. Again, the argument is largely economic.

Such a policy would reduce US control over the high end of the Cloud e-commerce value chain and EU online advertising markets. Currently European data is exposed to commercial manipulation, foreign intelligence surveillance and industrial espionage. Investments in a European Cloud will bring economic benefits as well as providing the foundation for durable data sovereignty.

Further along, the report notes the different ways the NSA scandal has been understood inside and outside the US. Inside the U.S. a key issue was whether the NSA has been spying domestically, on U.S. citizens, and the implications of that question for domestic data security. Abroad, the report notes, people are understandably more interested in their own ability to protect personal data from the NSA. The briefing suggests E.U.-U.S. negotiations on data security, though efforts at such negotiations have failed previously.

…a casual reader would not understand that the intended target of surveillance was non-Americans, and that they had no rights at all. It seems that the only solution which can be trusted to resolve the PRISM affair must involve changes to the law of the US, and this should be the strategic objective of the EU. Furthermore, the EU must examine with great care the precise type of treaty instrument proposed in any future settlement with the US. [boldface as printed] Practical but effective mechanisms are also needed to verify that disclosures of data to the US for justifiable law enforcement investigations are not abused.

In sum, Europe’s still upset, and talking seriously and in public about how to protect itself from American eavesdropping. Yesterday, Slate‘s Ryan Gallagher flagged a want ad for a counterintelligence professional posted on a Parliament website last July, shortly after the Edward Snowden affair broke. The same body is housed in a Brussels building ID’d as an NSA target in the Snowden papers, according to the Slate report.

This article originally appeared at Pacific Standard. Pacific Standard is an arm of the nonprofit Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media and Public Policy.

27 Sep 13 | Digital Freedom, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Sudan

Reports of at least 50 dead have been received from Sudan.

There’s no trying to hide what’s happening within the urban centres of Sudan today. On Wednesday, September 25 at about 1pm, the Sudanese authorities completely shut down the country’s global internet for 24 hours. This happened against the backdrop of spreading peaceful protests following the regime’s decision to lift state subsidies from basic food items and fuel.

In the last few weeks, Sudan’s citizens have been feeling the burden of increasing prices as the Sudanese pound depreciated sharply, and purchasing power declined in a country where 46 percent of the population live in poverty. The lifting of subsidies was met with a popular outburst, especially after a public TV speech by President Omer Al Bashir made it clear that his government has no concrete solutions. He went on to mock the population saying they did not know what hot dogs were before he came to power.

The protests, which started in Wad Madani in Gaziera state, have so far spread to Sudan’s major towns including Nyala in war-struck Darfur. They have been met with unprecedented government violence in the Northern cities of Sudan which have traditionally been peaceful. Live ammunition has been used against protesters, many of whom are school students and youth in their early to mid twenties. By the third day of protests the death toll in Khartoum alone exceeded 100, and 12 in Wad Madani. There have been arrests amongst political leaders, activists and protesters, with more than 80 detainees from Madani alone.

Sudan’s government has cracked down violently, using live ammunition to disperse demonstrators.

Protesters are mainly calling for the regime to step down, with chants of, “liberty, justice, freedom”, “the people want the downfall of the regime”, and “we have come out for the people who stole our sweat”. These protests lack any political or civil society leadership, and so far not a single statement has come from the umbrella of opposition parties, the National Coalition Forces.

Crackdown on the internet and print media

The internet blackout imposed by Sudan’s National Congress Party (NCP) was an intentional ploy aimed at limiting the outflow of information, especially the very graphic images of protesters lying dead in the streets, as well as the images from hospital morgues showing protesters with fatal injuries to the head and upper torso areas. It is clear that this show of force is meant to frighten Sudanese citizens and deter additional protests. (Graphic Images: Street | Street)

This is not the first time the regime in Khartoum has shut down the internet. In June 2013 there was an 8-hour internet blackout during a gathering organized by the Ansar (an off-shoot of the Umma Party) that attracted thousands of people. During the protests last year, dubbed Sudan Revolts, the internet slowed down drastically on the night of June 29, before a large protest was announced.

Since the independence of South Sudan in July 2011, Sudan has also experienced a general clampdown on the media. On September 19, before the start of the protests on Monday, newspapers writing about the economic situation including Alayaam, Al Jareeda and the pro-government Al Intibaha, were confiscated. On Thursday, newspapers including included Al Ayaam and Al Jareeda, refused to print because of the government imposed censorship that prohibits any mention of the ongoing protests. Today Al Sudani and Al Mahjar newspapers (both pro-government) were confiscated, and Al Watan was not allowed to go to press.

The government of Sudan cut the country off from the internet as protests against the end of fuel subsidies spread.

With most citizens and activists relying completely on social media outlets and internet access through mobile phones to share information, footage and photos, the internet remains the only affordable means to communicate with the outside world. Other options, such as dial-up using modems are not viable for Sudan, as most people have no landlines to connect via modems and depend on mobile devices to access the internet.

During the internet blackout many reported that even SMS messages were blocked. And services such as tweeting via SMS were interrupted by the sole telecommunications provider that carries this service-Zain.

Popular anger and continuing protests

Contrary to the government’s intention the excessive use of force against protesters, the rising death toll and continuing rumours that the internet may be shut down again have not dissuaded citizens, but rather made them more angry and determined, with protests lasting long after midnight in Khartoum. As the streets of the capital and other towns filled up with security agents, riot police and armed government militias, citizens have nonetheless buried their dead in large and angry processions.

Today has been called Martyr’s Friday, in remembrance of all those who have fallen. Protests have been announced in all of Sudan’s towns. In some areas of Khartoum, citizens reported that they were not allowed into mosques for Friday prayers, and that the mosques had a heavy presence of security agents in civilian clothes. This move shows that the regime is anxious protests may follow after the prayers, as well as fearing the possible politicisation of the Friday sermons which may incite more anger.

Nonetheless, this has not deterred more than 2,000 protesters to congregate in Rabta Square, Shambat Barhry (in Khartoum). While writing this, a protester called me to say his internet was not working, and described that even leaders from the communist party, Popular Congress Party and others were starting to arrive. I could hear him with difficulty, but chants in the background were clear, “ya Khartoum, thouri, thouri”—Khartoum, revolt, revolt.

So far one thing is clear: these protests are not a replay of last year’s summer protests that were mainly triggered by university students and youth movements. These are street-supported protests–something that previous protests lacked and a game changer for the NCP who is gradually losing its grip on power.

This article was originally posted on 27 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

This article was edited on 5 November 2013 at 13:50. The article originally stated that the internet blackout took place on Wednesday 26 September. It took place on 25 September.

27 Sep 13 | Comment, Digital Freedom, News and features

Californian legislators have come up with a plan that would help teenagers delete their online presence, or at least the parts that are held by social media sites.

It’s an incredibly tempting notion: as the Independent’s Grace Dent points wrote this week:

If only I could have rounded up my past in binliner at 18 and set it alight. All those love letters, declaring undying love now sitting in the lofts of boys I can’t remember the names of, the missing diaries, the angry letters sent to the NME, some petulant letters sent to Mars Inc. about the Marathon to Snickers name change. How lovely if aged 18, following a short button pressing ceremony I was officially no longer a twerp.”

Dent is writing about a teenage past pretty much pre-Internet, never mind pre-smartphone with 8 megapixel camera. I’m of the same vintage. There’s really very, very little of young me out there. Thank God.

It is different of course for teens today, who innocently post vast amounts of information about themselves online. We’re beginning to see the repercussions of that. Cast your mind back to earlier this year and the case of 17-year-old Paris Brown, the recently elected youth police and crime commissioner for Kent, who lost her salaried job after someone dug up a few stupid things she’d posted on Twitter a few years previously. It’s depressing that people can be so unforgiving of children.

Much worse, Texan teenager Justin Carter could face jail after being charged with making “terroristic threats” during a Facebook argument about a video game.

Could an erase button solve any of this? I’m not sure. It is possible to get rid of one’s Facebook and Twitter accounts already, but will it be possible to erase all the mentions? The tagged photos and endless other footprints left online? I’m not so sure.

Moreover, I don’t know if it’s a really positive idea. If the web is to be part of everyday life, which we seem to want to encourage, then how does this initiative, essentially creating two different lifetimes, work?

At an Index on Censorship discussion on young people’s free speech online last Monday, an interesting idea emerged: should the joys and dangers of social media be taught in school? Like sexual education is taught? Social media, like sex, is part of life and people should be taught about it sensibly. The worry with a button that effectively erases one’s adolescence is that it may mean we avoid talking about positive social media use for teens in the first place.

On top of all this is broader society. Should we not be a little more forgiving of young people’s indiscretions? A little less judgmental?

We should be able to to delete information we’ve put online about ourselves, absolutely. But we should also be creating an atmosphere where young people don’t feel the need to take the nuclear option and erase years of thoughts, ideas and memories.

This article was originally published on 27 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Sep 13 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Pakistan

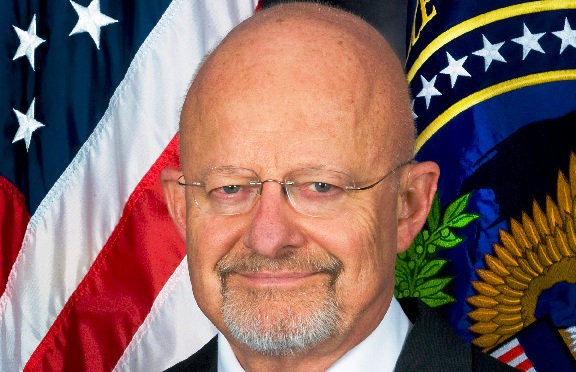

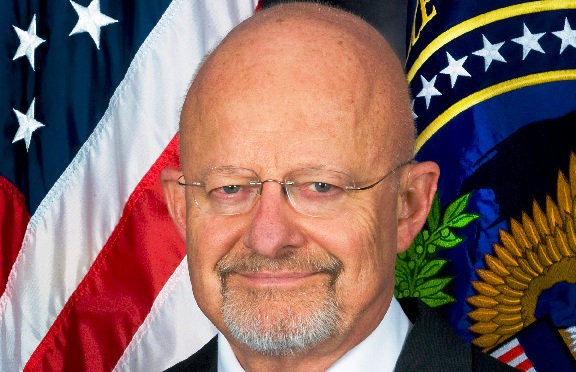

NSA head James R Clapper

Dear Mr Clapper,

We are reaching out to you with important information that may be of crucial value in preserving your organisation’s integrity and purpose. As citizens of Pakistan, we feel there’s an unexplainable bond, a debt if you’d like to call it, that we owe to your agency; after all, we are the second most interesting people in the world in your ever-vigilant eyes. We are therefore writing to raise with you an issue of extreme importance & national security.

The information here is highly critical and can jeopardise our security if leaked; you see, the world does not really recognise whistleblowers as yet. We trust you to keep this to yourself.

The government of the United Kingdom and the government of Canada are both involved in activities that may be considered by you a grave violation of the sovereignty of your organisation. Independent research group The Citizen Lab – truly independent as they do not take government or corporation support – has revealed the presence of Netsweeper and FinFisher equipment in Pakistan, belonging to companies with headquarters in Canada and the United Kingdom respectively.

It is baffling that these two respected governments, your notable allies, have not taken the necessary steps to disable these equipments, or at the very least stopped the trade. FinFisher for one has been used actively in Bahrain, aiding the Bahraini government in cracking down on activists, including an activist your government has lauded and awarded. This seems to us as a painful revelation that shows a lack of faith in your agency from your own allies.

As far as we are concerned, we don’t understand why these companies need to sell this equipment to our government, and why our government needs to spy on us when your organisation has dedicated staff, labour, and, not to forget, extensive budgets to be able to do just that.

With a heavy heart, we hope to keep you informed (just in case you missed out) and hope that you will take strict action to strike down these Weapons of Mass Surveillance that are in blatant disregard, grossly disrespectful, and a gross violation of your integrity and the national security values of your country.

Yours sincerely,

Citizens of the Second Most Interesting Nation in the World

SIGN INDEX’S PETITION AGAINST INTERNET SURVEILLANCE

This article was originally posted on 27 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Sep 13 | News and features, United Nations

Image SeanPavonePhoto / Shutterstock.com

“The transition to sustainable development must be based on a commitment to eradicate poverty. This is an indispensable requirement; a matter of human rights”, UN General Secretary Ban Ki Moon declared yesterday at a special event discussing the future of global development.

The day-long session took place at the 68th General Assembly titled ‘Beyond the Millennium Development Goals: The Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda’. Its aim is to figure out what could be the world’s next unified development strategy when the UN’s eight Millennium Development Goals (MDG) ‘run out’ in 2015.

While it may seem like your average meeting of the diplomatic elite, this week’s events marks one of the most significant events in global development since the Millennium Declaration in 2000. The conclusions will guide a large-scale poverty eradication strategy that will have a very real impact on the lives of millions around the world. It is vital to get it right, and in order to do that, it has to promote and protect freedom of expression.

The major criticisms levelled at the MDGs were the opaque manner in which they were set up, and the minimal focus civil liberties. The right to freedom of expression was all but ignored completely.

So when the time came around to consider the road ahead for global development, many, including the Beyond 2015 project, argued that human rights had to play a fundamental part. “Development will not deliver for the poorest and most marginalised people in the world without a strong focus on human rights,” Human Rights Watch recently stated.

A vital right in this respect is the access and ability to express yourself freely and without fear. As Index has argued before, freedom of expression underpins most other rights and allows them to flourish. The ability for people on the ground to express their opinions, needs and wants, criticise and hold their leaders to account and access a free and fair media, play vital parts in the healthy development of a society. It is the marginalised people this development strategy would seek to help that face the most acute barriers to freedom of expression. If people can’t express what is hindering their development and if no-one is listening, how can their situation truly improve? This is a vicious circle that can only be broken by a strong commitment to universal freedom of expression.

The positive thing is that the powers that be appear to agree with this. Ban Ki Moon’s recent report “A life of dignity for all”, presented at this General Assembly, argues that “We know that upholding human rights and freeing people from fear and want are inseparable; it is imperative that we do more to act on this basic truth.”

The High Level Panel on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, tasked with scoping out the options ahead of this General Assembly, presented their findings in a report in May. They recommended it should include guarantees for freedom of speech, association, peaceful protest, and access to independent media and information. They also argued for increased public participation in political processes and civic engagement, as well as guarantees regarding peoples’ right to information and access to government data.

As opposed to the MDG process, this time around complex, important decisions about world development were not made behind closed door. There was a nine-month consultation process that included input from indigenous peoples, migrants, women’s groups, in addition to thousands of civil society groups and businesses from around the world. Through The World We Want project, a million people from across the world gave their thoughts on development in an online survey.

But the work is far from over. The General Assembly will set the stage for the future of global development, but not in stone. The MDGs avoided politically difficult topics like freedom of expression to ensure widespread support – even from countries with poor record on civil liberties. Unwavering commitment to human rights is needed over the next two years to avoid a watered down agenda.

The MDGs have laid some important foundations. The fact that we’re even discussing how to continue the project post-2015, is to its big credit. For the next step of a global development push, however, human rights including freedom of expression, have to be at the core. People have to be given a voice in their own development process.

26 Sep 13 | Bahrain, Guest Post, News and features

A pro-democracy protest in January 2013. (Photo: Moh’d Saeed / Demotix)

On 17 September, Bahraini authorities arrested Khalil Marzouq, a prominent member of the opposition Al Wefaq group. Following an interrogation that lasted over seven hours, he was charged under newly amended terrorism laws leading, to Bahrain’s main opposition party to pull out of the National Dialogue.

The credibility of the dialogue itself has come under criticism, as the government has carried on with its crackdown on dissent throughout the discussions. Amnesty International points to this irony by noting that authorities have been “flaunting” the National Dialogue as the central reason for canceling the visit of UN Special Rapporteur on Torture back in April, yet have nevertheless moved towards arresting participants. The actions have been criticised as measures intended to “wipe out the opposition”.

There has also been an attempt to dismember the Ulama Council of Shia religious leaders, led by Sheik Isa Qassim. Additionally, in a recent development, Bahrain’s Public Prosecutor has also been re-elected as a member Member of International Association of Prosecutors Executive Committee, despite Bahrain’s human rights abuses and continued prosecution of human rights defenders and political activists.

The results have been critical; Bahrain has been leading a campaign of repression with impunity since the protests began.

The recommendations of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry and the United Nations Universal Periodic Review have been largely ignored in practice, and instead practical moves have been taken within the national legal framework to target the opposition.

New terrorism laws have been announced implementing measures to withdraw citizenship and setting tough penalties against anyone that the regime dubs a terrorist. Newly implemented decrees have also imposed sweeping bans on all forms of peaceful protest in the capital Manama, alongside tough penalties for parents and guardians of juveniles who take part in unlicensed demonstrations.

Such measures have always been imposed in Bahrain, however the move to practically implement them within national law has lead to a new era of political polarisation.

Media personnel and citizen journalists reporting on human rights abuses have also found themselves targetted. In August, citizen journalist Mohamed Hassan was arrested and his equipment seized during a midnight raid on his home. Shortly following the events, his lawyer AbdulAziz Mosa was also detained after tweeting claims that Hassan had been tortured. The Bahrain Centre for Human Rights reported that he had been interrogated for over three hours, beaten on his back and lower abdomen and “forced to confess under mental and physical coercion”.

More recently, on the 24 September, a US citizen Tagi Al Maidan was convicted and sentenced under charges relating to attempted murder: charges he consistently denies. Al Maidan has long complained of torture during his detention. Torture was confirmed to have been a systematic practice in Bahrain by the BICI despite the government’s denial that it takes place.

Allegations of torture and ill-treatment continue to surface following the report, not only in places of isolation away from security departments, but during CID and Public Prosecution interrogations. During a meeting between Bahrain’s Prime Minister and Mubarak Bin Huwail, recently acquitted of torture, the PM commented to Huawail that “these laws cannot be applied to you. No one can touch this bond. Whoever applies these laws against you is applying them against us. We are one body”.

Despite the lack of international accountability for Bahrain’s rights abuses, these recent developments have forced some states to show public concern over the future of the Kingdom. At the 24th session of the UN Human Rights Council, 47 states expressed concern through a joint-statement over the deterioration of the human rights situation in Bahrain, its newly implemented terrorism laws (specifically revocations of citizenship), the increase in violence and the imprisonment and harassment of persons exercising their internationally recognised freedoms.

The European Parliament has similarly expressed concerns over the deteriorating situation where “human rights activists are facing ongoing systematic targeting, harassment and detention in Bahrain”.

The uprising looks to continue amidst the absolute subjugation of any form of dissent. Opposition have been branded and targeted as “terrorists” — a term undefined in Bahrain national law — and as anniversaries are set to be re-lived in the new year, the movement is subsequently set to escalate in dissent.

This article was originally posted on 26 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Sep 13 | News and features

(Photo: David von Blohn / Demotix)

This article was originally published at Indy Voices

What’s happened to Edward Snowden and his revelations about the National Security Agency’s surveillance programme? As stories keep emerging from one of the largest leaks in US history, we learn more and more about the Americans’ ability to monitor communications, but seem less sure how to respond. Most people would acknowledge that the state does retain some right to monitor suspect activities. But this is a very different proposition from the population-wide mass surveillance suggested by the documents leaked by Snowden. Clearly the balance has tipped much too far in favour of default data gathering. So how do we move it back?

This is a complex discussion, and it’s not really being had in the UK right now. The Guardian’s Simon Jenkins has suggested an establishment conspiracy has kept the public from talking about this – it’s certainly true that the response here has not been on the level of that in other countries (not least in Brazil, where a national Internet redesign to avoid US surveillance is being considered).

But part of the problem here is not simply that people have been shielded from the discussion on surveillance, or that people don’t care. It is that people do not know what we are supposed to do about this. Who do we appeal to? What do we want?

This is where the European Union can come into its own. An Englishman’s home may be his castle, but nowhere is protection of privacy given more credence than in Brussels and Berlin. A horror of Soviet-style surveillance of citizens runs deep in many European institutions and nation states, particularly those that had hands-on experience. The most powerful person in Europe, Angela Merkel, remember, was a citizen of Stasiland.

The European Parliament’s Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Committee (Libe), has set out to investigate claims of surveillance and examine what the EU can do about it. UK Labour MEP Claude Moraes has been charged with reporting on the Committee’s findings by the end of the year.

The parliament will be considerably aided by a 36-page briefing by independent surveillance researcher Caspar Bowden, who was helpfully mapped out the history of US and UK surveillance, and overlap with the European Union, all the way back to Alan Turing’s work with US spies in 1942.

Bowden comes up with several recommendations for Europe: the development of a “European cloud”, the revoking or renegotiation of mechanisms that allow US companies to gather data from European users, and, significantly in the case of the Snowden revelations, “systematic protection and incentives for whistleblowers”.

The European parliament investigation is welcome. But in reality, there is only a certain amount the parliament can actually achieve. The real power will, in the end, rest in the will of the governments of the respective European Union countries to act. Europe’s cyber strategy already states that “increased global connectivity should not be accompanied by censorship or mass surveillance”. But it’s time EU leaders acted on this.

That’s why Index on Censorship, along with dozens of other groups, including Amnesty, Reporters Without Borders and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, as well as stars and activists such as Bianca Jagger, Stephen Fry and Cory Doctorow, is petitioning European leaders directly. The next European Council Summit takes place at the end of October. We want every European government head there to publicly take a stand against mass surveillance.

The European Union, founded in part as a democratic bulwark against the authoritarianism of the eastern bloc, has a chance to stand out in the world against surveillance and for the rights of free speech and privacy. In the coming decades, power will be defined by who controls information: Europe, as a powerful democratic force, should work to ensure that its own ordinary citizens and people around the world are not left impotent.

Sign the petition telling EU leaders to stop mass surveillance here

25 Sep 13 | India, News and features, Politics and Society

India’s President Pranab Mukherjee (Photo: Wikipedia)

In September 2013, India’s President Pranab Mukherjee spoke about the inviolable right to privacy that citizens of India must enjoy, at the annual event of the Central Information Commission (CIC), a body constituted by India’s Right to Information Act, 2005.

Both the Act and the CIC have empowered ordinary citizens to submit applications requesting information from government bodies, injecting a new phase of transparency in an infamously opaque bureaucracy. In fact, the RTI Act has been born of, and has encouraged, large RTI ‘movements’, that have exposed layers of corruption in numerous schemes across various government departments.

For citizens, the fact that a government official has to release information regarding budgets, forms, decisions and other facets of public governance has led to the belief that unchecked corruption might finally simmer down, and that they are not longer helpless against the system.

However, as the RTI movement has matured over the last decade, serious questions of privacy protection have also started making their way into public discourse. The Act itself excludes a number of security and police agencies from having to divulge any information, and private companies and NGOs do not fall under the Act.

However, political parties that do fall under the act are furiously trying to legislate their way out from under the scanner. In fact, this move, supported by the ruling government that helped bring in the RTI has attracted a lot of criticism and well earned scepticism from the public. In a report on the matter, one of India’s biggest English news channels, NDTV, wrote, “The government decided to amend the law after political parties opposed the Central Information Commission’s order in June that six political parties including the Congress and the BJP will be under the RTI as they were substantially funded by public money. This would mean political parties would have to disclose campaign funding or how members voted during a secret ballot.” Indicative of the mistrust between government and the public, the report was called ‘Divided on everything else, political parties unite against RTI Act.’

Therefore, when the conversation turns to a conflict between the right to information and privacy, in India, it can often become muddled. It can seem that wrongdoers might attempt to hide behind the excuse of ‘privacy’. However, there is no escaping that protecting individual privacy is a genuine concern.

Many countries across the world that have enacted national RTI Acts also have privacy laws that carefully spell out the limits to which information about individuals can be disclosed. In general, information about personal life, sometimes including medical information, is exempt from RTI. Should names be revealed from all official documents, are all court proceedings public? And finally, do some people necessarily lose some privacy because of a ‘public interest’ test?

The World Bank Institute released a paper that describes RTI and privacy as “two sides of the same coin, essential human rights in modern information society.” It also goes on to add that, “privacy laws can be used to obtain information in the absence of RTI laws and RTI can be used to enhance privacy by revealing abuses,” and that both have been designed for accountability.

India does not have a privacy law in place right now, although what should be in the law has attracted considerable debate. Therefore, the contours of privacy in the RTI gambit have resulted from various decisions and court orders given over the years. For example, in 2011, the then chief information commissioner of the CIC informed India’s Reserve Bank of India that it had to reveal information, even if it meant public confidence in the institution might be adversely affected. And, as recently as early September 2012, the Mumbai High Court ruled that “disclosure of personal information in respect of service record, income tax returns and assets of an individual is illegal unless it is necessary in larger public interest.” This judgement protected the individual against any disclosure that had nothing to do with public interest, but instead caused unwarranted invasion of privacy.

There have also been reports that some RTI applications are filed only to be a nuisance, with cases of RTI being used to blackmail public officials, with the threat of burying them under paperwork. In April 2013, one applicant was fined for filing over 100 applications.

Moving ahead, President Mukherjee’s speech indicated that public authorities should be proactive and voluntarily put information in the public domain for the use of citizens, effectively inculcating a culture of transparency from the beginning.

However, until that happens, one can assume that the citizen will most certainly have to rely on the RTI for full disclosure about its government’s activity, and the government will have to be wary of those using RTI applications for ulterior purposes. Most importantly, the individual right to privacy should not be lost in this paper war, between the two sides of the same coin.

This article was originally posted on 25 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Sep 13 | Uncategorized

Nelson Mandela’s legacy has been “too easily dismissed”, South African editor Nic Dawes tells Index on Censorship magazine in the latest issue.

In an interview for the magazine, Dawes, who has just left his job as editor at South Africa’s Mail & Guardian for a new job at the Hindustan Times, said: “His legacy is being brought back to us.”

South Africa was going through a phase when the people who brought us press freedom “now seek to restrict it”.

“We are going through a very classical process, what happens when a liberation movement has been in power for a while and starts to see its hegemony challenged and then reaches for a convenient lever to limit that challenge.”

Read the full interview with Nic Dawes in the new issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Listen to the podcast below or click here.

25 Sep 13 | News and features, Religion and Culture

A publicity shot from Lucien Bourjeily’s latest play

Banning a work of art, a book or a play says more about a society and its temperament than anything else. As free speech and readers mark Banned Books Week, Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley looks at Lebanon, where the country’s Censorship Bureau has recently flexed its muscles

In the past few weeks, Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily has had his play Will It Pass or Won’t It? banned by his government. Ironically, the play is about censorship, specifically the process in Lebanon whereby plays are passed by the Censorship Bureau of the General Security Office — or not performed.

Bourjeily’s play dramatically challenged that process. But the censors did not see the funny side of his finger poking at a system that involves playwrights putting their words through the wringer of a censorship process, before being squeezed out again.

The censors came up with a variety of reasons why the play should not be shown, ranging from it not being “realistic” (surely missing the point of fiction there), to it not being good enough. Those in charge decided it was not for the people to decide whether it was worthy of their time, it was for them. And with that the play was to be banned.

Banning a work of art, a book or a play says more about the society and its temperament than anything else. Some nations are less than confident about themselves; they are clearly worried that if their ideas are questioned they will be weakened and their power diminished. Ban a book or a play if you worry that by talking an idea or a principle that discussion will somehow harm society. If you don’t worry about your values, principles or laws being discussed since you are perfectly willing and able to defend them, then there is no need for a work of art, book or play to be censored.

A robust, vibrant and creative society is a place where open discussions can take place, and Index on Censorship magazine, throughout its life, has often helped publish some important writings which were censored in other parts of the world, and smuggled out to Index. When the Soviet Union still existed, great thinkers there were censored and silenced, and Index helped their voices to be heard. Today it still seeks to help publish those whose words and ideas are silenced by their own governments. In its winter edition it will publish an extract from Bourjeily’s play so that readers can make up their own minds about whether it is worth performing.

Healthier societies do not hold back debates, even when they may disagree with them. They allow them oxygen to see how worthy of consideration they are. Ideas can shock or offend. Robust societies can cope with that, and even feel healthier for it.

Prodding and debating, as any writer, politician, thinker, inventor or scientist knows, is good for an idea or a thesis; it might be flawed, disproved or ignored. Or not. In the same way that scientists depend on their ideas being tested to see if they work and should be developed, leaders of nations should expect their proposals, their laws or processes to be prodded, debated and discussed. And that is what happens in a book or a play.

In a recent interview, Bourjeily said he felt that the Lebanese were treating their people as children, not allowing them to make their own decisions. Because of that, they were no longer expressing ideas in public, because of the consequences. They are self censoring, they are not exploring. None of that is good for any developing society. Inventors and scientists are attracted to those vibrant centres as are artists and writers. Across the world and throughout history those buzzing hives of thought have led the globe financially and culturally. As ever an open lively society attracts the world’s leading thinkers and creators, a place where censorship and fear is rife does not. Leaders of the world take note.

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship, an award-winning magazine, devoted to protecting and promoting free expression. International in outlook, outspoken in comment, Index reports on free expression violations around the world, publishes banned writing and shines a light on vital free expression issues through original, challenging and intelligent commentary and analysis, publishing some of the world`s finest writers.

To mark Banned Books week, Index’s publisher SAGE has freed up access to the full archive of Index on Censorship through 28 Sept. Access articles here: http://ioc.sagepub.com/

This article was originally posted on Sage Connection

24 Sep 13 | News and features, Uganda

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

In May this year, the Ugandan government closed two newspapers. The crime The Monitor and The Red Pepper newspapers committed was publishing a letter by the now renegade former Coordinator of Security Services, General David Sejusa, in which he claimed that President Yoweri Museveni was grooming his son Muhoozi Kainerugaba to succeed him. In the same letter, General Sejusa claimed that there was a plot to assassinate all army officers and senior government officials who are against the president’s succession plan.

The letter had been written to the Internal Security Organization (ISO) boss to investigate the allegations, but was leaked to the media. Despite this, the government went ahead and closed the two media houses which had run the story for two weeks. They were only allowed to reopen after meetings with the minister of internal affairs, where the editors were told that government would not hesitate to close the media houses for good if they did not stop “reporting irresponsibly.” These are the only privately owned dailies in the country.

This was not The Monitor’s first run-in with the government. At its inception in the early 1990’s, it was the only privately owned daily that competed with the government-owned New Vision. New Vision towed the government line as a mouthpiece and enjoyed all the advertising deals from all government ministries and agencies. The Monitor was totally denied all government adverts, with the intention of killing it off because it was the only paper that was questioning government decisions on different issues. It was the readership plus some support from private businesses that kept it alive. The African Centre for Media Excellence (ACME) has also criticised the paper and its sister FM station, KFM, for bending under government pressure. This came after it pulled down a critical story about the president, claiming that it had been badly written.

Print media is not alone in being targeted. During the 2009 riots that rocked Uganda, the government closed five privately owned FM radio stations reporting on it. Four of them were reopened after six weeks, after they had publicly apologised to the president and promised never to do that again. Central Broadcasting Services (CBS), however, was closed for over a year. It took a lot of pleading to the president from the media, church, monarchy and other wealthy and influential people to reopen CBS. Since it went back on air, most of the political discussions were bumped off air and some individuals who government felt were anti-establishment were barred from appearing as panelists on the different radio talk shows.

To add to the problem, the government also directly controls a wide range of media. New Vision is run under the government-owned Vision Group and is building up a powerful media conglomerate with four other newspapers publishing in local languages, three television stations, three radio stations in the capital Kampala, plus other local radio stations in at least all the other regions of the country. All these are strictly government mouthpieces, and management will not allow opposition politicians or activists to use these platforms to reach the masses. The national broadcaster, Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC), which runs the national television station and a multitude of radio stations in the countryside, is also tightly under government control.

Furthermore, while Uganda is seen in the East African region as having the best and less repressive media legislation, the government has of late tended to make amendments to the existing media laws to make them restrictive. The African Media Barometer (AMB), which is made up of leading media practitioners in the country from private and government-owned media houses, as well as lawyers and representatives from civil society, reported in 2012 that there are a few positive developments in Uganda with the licensing of more print and electronic media outlets. However, AMB also notes that the media freedom declines ahead of elections as the government grows increasingly nervous and attempts to clamp down on freed speech. Private media houses, especially radio stations, also practice self-censorship in order not to annoy the powers that be.

Ibrahim Bisika from the government’s Media Centre says the friction between media and government arises out of “editorial mismanagement” where media houses publish stories that bring them in direct confrontation with government. Moses Serwanga, a director at the Uganda Media Development Foundation (UMDF) says that media freedoms in the country are getting curtailed because of the creeping political dictatorship where political leaders do not want to leave office.

24 Sep 13 | Campaigns, Press Releases

Nearly 40 free speech groups from across the world are calling on the European Union to take a stand against mass surveillance by the US and other governments. The groups have joined a petition organised by Index on Censorship, which has already been signed by over 3,000 people. Celebrities, artists, activists and politicians who have supported the petition include writer and actor Stephen Fry, activists Bianca Jagger and Peter Tatchell, writer AL Kennedy, artist Anish Kapoor, blogger Cory Doctorow and Icelandic politician Kolbrún Halldórsdóttir.

Actor and writer Stephen Fry said:

‘Privacy and freedom from state intrusion is important for everyone. You can’t just scream “terrorism” and use it as an excuse for Orwellian snooping.’

Chief Executive of Index on Censorship Kirsty Hughes said:

‘A few of Europe’s leaders have voiced their concerns about the NSA’s activities but none have acted. We are demanding all EU leaders condemn mass surveillance and commit to joint action stop it. People from around the world are signing this petition because mass surveillance invades their privacy and threatens their right to free speech.’

As well as calling for Europe’s leaders to put on the record their opposition to mass surveillance, the petition demands that mass surveillance is on the agenda at the next European Council Summit in October.

The petition is at: http://chn.ge/1c2L7Ty and is being promoted on social media with the hashtag #dontspyonme

The petition is supported by Index on Censorship, Amnesty International, English PEN, Article 19, Privacy International, Open Rights Group, Liberty UK, Reporters Without Borders, European Federation of Journalists, International Federation of Journalists, PEN International, PEN Canada, PEN Portugal, Electronic Frontier Foundation, PEN Emergency Fund, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, National Union of Somali Journalists, Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, Catalan PEN, Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ) – Malaysia, Belarusian Human Rights House, South East European Network for Professionalization of Media, International Partnership for Human Rights, Russian PEN Centre, Association of European Journalists, Foundation for the Development of Democratic Initiatives – Poland, Independent Journalism Center – Moldova, Alliance of Independent Journalists – Indonesia, PEN Quebec, Fundacja Panoptykon – Poland, International Media Support, Human Rights Monitoring Institute – Lithuania, Warsaw Branch, Association of Polish Journalists, The Steering Committee of the Civil Society Forum of the Eastern Partnership, South African Centre of PEN International, Estonian Human Rights Centre, Vikes Foundation, Finland

For further information, please contact [email protected]