09 Feb 23 | FEATURED: Katie Dancey-Downes, News and features, Turkey

Monday’s devastating earthquakes in Turkey have led to the loss of thousands of lives but one of the government’s responses to the disaster is troubling. At midday on Wednesday, Twitter was restricted in Turkey. The quake caused a number online connectivity issues, but this was not the reason that users couldn’t get onto Twitter. It was a direct response to political criticism.

This is according to Alp Toker, founder and director of NetBlocks, which tracks cybersecurity and digital governance.

“Up until Wednesday, we were tracking connectivity issues in real time, on the ground,” Toker told Index, describing regions in southern and central Turkey that have been laid waste by earthquakes. Knowing which regions are offline and have infrastructure impact, is useful for rescue operations, he explained.

“Suddenly, on Wednesday afternoon, we observed filtering of Twitter — which was unexpected — and we were able to verify that this was unrelated to the connectivity issues happening in the south, and that this was targeted censorship of Twitter.”

NetBlocks uses the same techniques that they developed to track internet shutdowns, validating and reporting in real time. It verified the information through its monitoring network, checking the connections, the ability to connect, and looking at the underlying reasons for the service not working. On closer inspection, they discovered that the filter had been applied at ISP (internet service provider) level using an advanced technique that’s been deployed before in Turkey, preventing users from accessing Twitter. This is the 20th such incident that NetBlocks has tracked in Turkey since 2015.

“These mass censorship incidents happen after political scandals, they happen after terrorist attacks, they happen in a variety of circumstances — also during military operations in the south — but it’s the first time that they’ve been applied in the aftermath of a natural disaster,” Toker said.

Turkey’s government has faced intense criticism following the earthquake. Some of those critics, including journalists and academics, have been detained and arrested.

“It was intentional mass censorship applied at a time when people are really using Twitter and relying on it to seek help, and to ask for equipment supplies, but also to get in touch with loved ones and see if friends and family are okay. The idea that such a vital tool would be withheld is shocking,” Toker said. “There are reports that people under the rubble use Twitter to connect with the outside world. So it’s literally a lifeline in that context.”

When phone lines are overloaded, he said, using Twitter to reach out for help makes sense.

“All of these use cases have been an absolute reminder that freedom of expression, the right to impart knowledge, is more vital than ever in a crisis and must not be curtailed.”

By midnight, 12 hours later, the restriction was lifted. It came following an outcry, and NetBlocks’s role in validating and reporting the restriction.

What very nearly happened, Toker said, was an internet freedom protest outside the IT Ministry’s office in response to the restriction. Twitter was back before the planned protest took place.

The restoration of Twitter might seem like a success story, but it came at a price. While people were fruitlessly refreshing their timelines, something else was happening.

“Turkish authorities had a meeting with the head of policy at Twitter,” Toker said. “They pressured Twitter into complying more thoroughly with their own takedown demands in future, and they spoke about what the Turkish State perceives as disinformation, but which many others perceive as legitimate free speech and criticism.”

Toker said that Elon Musk’s company is once again in the fray of the Turkish filtering and censorship regime. And as the disaster response continues in the wake of the earthquake, criticism will continue on and offline.

“The big question now is whether Turkey is going to increase its demands for censorship of individual posts from Twitter, and whether Twitter is going to comply with that,” he said. “If Twitter does comply, it’s going to be the first time the company has really engaged in that level of censorship since Elon Musk’s takeover.”

If Twitter complies with Turkey, he said, the door might also be cracked open for censorship demands from other countries.

09 Feb 23 | BannedByBeijing, China, Greece, News and features, Tibet

A few months ahead of the Beijing Winter Olympics, in October 2021, activists gathered at multiple locations in Athens to protest China’s hosting of the Games. In an alarming turn of events, Greek police arrested several of the activists. Some were arrested for unfurling banners, others for simply handing out fliers or, even just attending the “No Beijing 2022” events. Some were released without charge, others were acquitted after trial. For three activists, their trials were postponed until later in 2023.

Photo: Free Tibet

Before travelling to Greece, the activists – who were mostly Hong Kongers and Tibetans from Switzerland, the USA and Canada – tried to engage with International Olympics Committee (IOC) officials. They explained that hosting the Olympics in an authoritarian country that commits genocide was a violation of the Olympic Charter, which ensures that the games promote “a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity”. However, their arguments fell on deaf ears. Frances Hui, the director of “We The HongKongers”, told Index that IOC officials dismissed them, saying “you’re young, this is a complicated issue.”

Another activist, Zumretay Arkin, director of the World Uyghur Congress Women’s Committee, told Index that protesting at the Olympic flame lighting ceremony “was an opportunity for us to counter Beijing in Greece.”

While the activists knew there are always risks involved in protesting, they were not particularly worried. The most common tactic used to silence dissidents abroad – threatening the safety of loved ones – could not work as most activists involved had no direct family left in their homelands. Tsela Zoksang, a Students for Free Tibet member, told Index: “I have the privilege to raise my voice up against the CCP, unlike many communities who remain under the brutal rule of the CCP, and so I think I have a duty to amplify their voices and their stories.” Greece’s position as a member of the EU also reassured the protesters. According to Pema Doma, one of the activists and Executive Director at Students for a Free Tibet, they believed it “very unlikely that a country of the EU would act on orders of the Chinese government”. These beliefs were unfortunately misplaced.

Fern MacDougal, Jason Leith and Chemi Lhamo outside the Greek jail after their action. Photo: Free Tibet

CCP involvement

On 18 October, activists congregated outside the flame lighting ceremony. The activists planned to stand outside the security cordon and hand out flyers to journalists as they entered the Temple of Hera.

The activists were first approached by a Greek police officer curious about their activity but were left undisturbed. This soon changed. According to four activists that Index spoke to, the Greek officer spoke to an individual who identified themself as and was dressed in the uniform of, a member from the Chinese Embassy. The Greek officer insisted that “They’re just sitting there, I don’t see why they shouldn’t be allowed to sit there”. According to the activists’ retelling, this was met with the firm instruction to “make them leave. Tell them they can’t stay here”. They were moved from the entrance car park to a public pavement.

The activists had spotted other plain-clothed Asian men earlier taking photos of them. These same men approached the Greek police, and after a short discussion the activists were detained by Greek police officers. They were arrested without being informed of their rights and taken in unmarked cars to Pyrgos Police Station.

The Greek police possess broad powers to arrest activists for unsanctioned actions. Avgoustinos Zenakos, an investigative journalist from the Manifold Files, told Index: “The Greek police interpret these laws in their favour…This means whether it is abused or used in an honest way depends on the culture of the police rather than the letter of the individual law.” During an official visit to Greece, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention reported that they received “credible information involving non-nationals in pre-trial detention who were detained exclusively on the basis of police testimony, including when there was other evidence that did not support the guilt of the persons involved.”

The protesters believe that the decision to arrest them was not made by the police alone. Doma told Index: “We knew right from the beginning it was the Chinese Embassy staff directing the Greek police quite directly, quite closely, you know, telling them exactly what to tell us”.

The next day, another group of activists were detained after holding a press conference to discuss the CCP’s human rights abuses to members of the media. The event was monitored by unknown individuals, some of whom attempted to stare down and harass the activists. When some of the activists confronted the individuals and asked them where they were from they laughed before replying, “We’re from China”. Tsering Gonpa, a Tibetan Youth Association of Europe activist, and Tenzin Yangzom, Grassroots Director at Students for a Free Tibet, climbed into a taxi together after the event and immediately heard sirens. Their passports were confiscated and they were escorted to the Athens police station.

“We were extremely shocked by the CCP’s influence and leverage in democratic Greece. We knew the situation was bad, but we certainly didn’t expect this level of transnational repression,” Yangzom told Index.

According to Zenakos, to find criticism of Greece’s relationship with China, including Chinese state ownership of key Greek assets and Greece’s involvement in key initiatives such as the 16+1 grouping of countries and China’s “One Belt, One Road” strategy, “you would have to dig deep.” These all raise questions as to whether increasing economic entanglement is leading Greece to become overprotective of its relationship with China. For instance, in 2016 Athens pushed for an EU statement on the South China Sea to be amended to remove criticism of Beijing and a year later it vetoed an EU statement at the UN Human Rights Council condemning human rights abuses in China. According to media reporting, this was the first time the EU didn’t make a statement of this nature at the council.

Mistreatment in the police stations

On 17 October 2021, Tesla Zoksang and Joey Siu, and one other anonymous activist, planned to install a banner onto the outer-walls of the Acropolis. Within about two minutes of ascending, a security guard approached and cut down the banner. The activists remained perched on the scaffolding watching police cars arrive before they were escorted down. Greek barrister Alexis Anagnostakis, who represented the activists, told Index that “the activists’ removal from the protest site, their arrest, and their remand in police custody was a disproportionate interference with their rights for freedom of expression and assembly, as is their criminal prosecution.” Anagnostakis was also surprised by the escalation “since similar protests on the Acropolis reportedly have never before been prosecuted.”

According to Tsela Zoksang, at the police station during an interrogation, one activist who wished to remain anonymous, was told by Greek officials that a representative from the US embassy was there to see them. However, the representative later allegedly admitted to being from an unspecified Greek agency. With assistance from the non-profit Vouliwatch, Index submitted an FOI request to the Greek police, attempting to verify these claims but were denied the disclosure on the basis that Index does not have “specific legitimate interest”. Index has lodged an appeal.

Other detained activists were not informed of their rights or what crime they were alleged to have committed. When the activists detained outside of the press conference asked why they were being detained an officer told them “to be completely honest with you, I don’t know why we’re taking you with us but I got orders from the higher ups”.

They were asked to sign documents without an English translation. After refusing, Zoksang reported that the officers “began getting very angry and frustrated. They were saying, ‘You are disobeying me, you are disobeying the law.’ I said, ‘No, but I can’t sign something if I don’t know what it says’”. They were told they would be punished for not signing documents and giving their fingerprints but at the time of going to press, nothing has yet come of this. The activists were also asked a series of seemingly irrelevant questions such as their parents’ names. Given the potential involvement or presence of CCP-affiliated actors in their detention, they feared this information would be shared with the Chinese authorities, potentially imperilling their ability to travel and the safety of any family members in CCP-jurisdiction.

Every Tibetan is an activist

Chemi Lhamo, a Tibetan activist, explained to Index: “Every Tibetan that was born after 1959 is born an activist … because your existence is by default political in nature when you are born stateless.”

While the Games still went ahead, the campaign nonetheless left its mark. As Lhamo told Index, “There was a moment of time, in the world, in the busy world that we are in, when people stopped for a moment to ask, ‘what’s happening? What’s happening within Tibet?’”

The diplomatic boycotts were also found to have had a major impact on viewership. Yangzom told Index that the oppression of the activists was “vindication that the work that we’re doing is making an impact and we must be doing something right – so we mustn’t give up and keep raising our voices on behalf of Tibetans inside Tibet and all those oppressed.”

All charges against the Acropolis actors were dropped on 17 November 2022. Michael Polak, their British ‘Justice Abroad’ barrister, stated “It is hoped that the acquittals today will send a strong message that legitimate peaceful protest and assembly, of the type banned totally in China and Hong Kong, will be allowed even when it hurts the fragile sensibilities of the Beijing and Hong Kong regimes.”

Yet, the charges against others for attempting to “pollute, damage and distort” the historical monument of Olympia, punishable by up to five years in prison, still stand. The original trial against Lhamo, Jason Leith and Fern MacDougal was delayed before being again pushed back to November 2023. MacDougal told Index she worries “the delay in trial has the effect of both avoiding public discussion of the human rights violations that we took action based on and of obscuring the meaning of our action.”

Lhamo also noted that “it is another year of waiting, and having a pending court case has its own consequences which seem to unfold in various ways for us.” She elaborated to Index that she is “lucky” to have continued support from the lawyers and organisations, but the charge is a significant barrier for them to engage in more direct actions and affects their ability to travel. Yet she emphasised: “Don’t feel anxious for us [about the court case] … Let’s channel that energy of solidarity and support to the folks we are actually working for, those inside Tibet.”

08 Feb 23 | Iran, Iraq, News and features, Syria, Turkey

The murder of a 22-year-old Kurdish woman in Iran by the Gasht-e-Ershad ‘guidance patrols’ in September sparked protests worldwide. Celebrities cut off their hair and chanted ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ in support of the movement born out of her funeral. But ‘Mahsa Amini’ – as she is identified by the mainstream press – is a misnomer.

“Her formal name according to the Iranian state is Mahsa, but she was known as Mahsa only by the authorities,” British-Kurdish writer and organiser Elif Sarican told Index. “She was known as Jina to her family, friends and everyone that knew her. It’s what is on her gravestone.”

Sarican described the deliberate misnaming of Kurds as a tactic to deny their existence. The insistence on calling Jina the wrong name is “painful” she said, particularly when it’s by the mainstream media.

“It’s very difficult in Iran – not impossible – but very difficult, to have a Kurdish name,” she explained. “The Iranian state is very specific about the kind of Iran it envisages. Unfortunately, similarly to other parts of Kurdistan, Kurdish people cannot name their children with Kurdish names.”

In 1990, Sarican and her family migrated to London from Maraş in north Kurdistan, the site of one of the largest Kurdish massacres in contemporary Turkey. It was aimed at people just like her family – Kurdish Alevis.

The unrest in Iran, Sarican says, is representative of a universal Kurdish experience. It’s an uprising of people that have been denied for 100 years.

“‘Women, Life Freedom’, or ‘Jin, Jîyan, Azadî’ in Kurdish, comes from the Kurdish Women’s Movement,” she continued. “It’s a part of the Kurdish Freedom Movement founded by the imprisoned Abdullah Öcalan.”

Since the news of Jina Amini’s murder broke, the slogan has been adopted internationally as a symbol of solidarity. But the phrase, Sarican tells me, has been dissociated from its radical, political origins. It exists as a result of decades of struggle for women’s liberation and marked a big shift in the Kurdish Freedom Movement when women’s liberation was adopted and cemented as a core pillar.

“Bringing together women, life and freedom is what the Kurdish Freedom Movement ideology is. It’s based on radical democracy, ecology and women’s liberation. All of these coming together is the only way to achieve freedom.”

It’s no surprise, she explains, that Iranian protesters took inspiration and borrowed this slogan from their brothers and sisters in other parts of Kurdistan. “This is an expression of universal Kurdish struggle.”

The persecution of Kurds persists across the region. “100 years ago – and this year is the 100-year anniversary of the Treaty of Lozan – the Kurdish regions were divided into four nation states: Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. As a result of that, the experience of Kurdish people has been denied,” Sarican explained.

Kurdish language, culture and political expression are suppressed across the region. Fundamentally, they are denied the right to exist, she says. In Turkey, in the last 10 years, many Kurdish activists, elected MPs, mayors and councillors have been imprisoned. Although the Kurdish language is no longer formally banned in Turkey, it is repressed.

“To have education in your mother tongue is an international human right,” she explains. This is not a right granted to Kurds in Turkey.

While the treatment of Kurds in Iran, Syria and Iraq is brutal, Sarican says, it is limited to their own borders. Turkey not only oppresses Kurds in its own borders, but has invaded Syria, and continues to build military bases in northern Iraq.

“They are interfering in the lives of Kurdish people in at least three areas of Kurdistan. When the protests were happening in Iran and there was solidarity being shown in parts of Turkey, the police brutally cracked down on these demonstrations.”

Mournfully, she tells me that this month is the 10-year anniversary of the assassination of three Kurdish women by Turkish intelligence in Paris. In a disturbing mark of the anniversary, three more activists were assassinated in the same location just a few weeks ago.

“The Kurdish people are feeling unsafe not only in most parts of Kurdistan, but also in other parts of Europe,” Sarican continued.

Kurdish people constitute 10% of Iran’s population but make up about 50% of their political prisoner numbers. Many prisoners are denied proper health access, the most basic human rights, proper visits with family and connection with the outside world. Sadly, she says, many European states also extend these policies against Kurdish people in Europe.

“Kurdish communities are some of the most politically organised. The Kurdish freedom movement is not only one of the biggest political movements in the Middle East right now it is actually one of the largest social movements in Europe as well. [Criminalisation of our communities] really curtails and impacts the organising and protests.”

“Staying in tune with what’s happening in Kurdistan is of the utmost importance. It’s important that any future, whether it’s in Turkey or Iran – because it’s all connected, very very closely – is a future that works for the people. That’s a future of radical democracy, of ecology and of women’s liberation. Because otherwise these theocratic dictatorships will cement themselves.”

She stressed the significance of understanding the political projects that are already in existence across Kurdistan, instead of trying to impose a Western solution. “My call would be for people to understand the Kurdish Freedom Movement programme and what it’s offering. Read the memoir of Kurdish revolutionary Sakine Cansiz. Read the works of Abdullah Öcalan. Understand what the political project is and how we can work together to realise it. [The crisis in the Middle East] will only result in an actual, meaningful freedom if there is a political vision, led by the Kurdish freedom movement. It’s time we support that movement and come together to make sure that that is what the future of Kurdistan looks like.”

06 Feb 23 | Afghanistan, News and features

The UK government is failing journalists who were left behind in Afghanistan after the withdrawal of forces from the country in 2021.

As Britain mulled over the idea of a withdrawal of troops after 20 years in the country, it launched the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP) scheme to offer relocation of eligible Afghans to the UK.

When Kabul fell in a matter of days in August 2021 after British and US troops left, the Government launched Operation Pitting, the largest humanitarian aid operation since the Berlin airlift. This saw more than 10,000 eligible Afghan nationals as well as British residents evacuated following the rapid military offensive by the resurgent Taliban.

On 18 August 2021, then Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced a new Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme, which would resettle up to 20,000 people at risk, with 5,000 in the first year. This is in addition to those brought to the UK under ARAP.

At the time, the government said that the scheme would prioritise “those who have assisted the UK efforts in Afghanistan and stood up for values such as democracy, women’s rights and freedom of speech, rule of law (for example, judges, women’s rights activists, academics [and] journalists)” and “vulnerable people, including women and girls at risk”.

The evacuation of Afghan journalists to the safety of Britain has not happened.

Index on Censorship has been contacted by a large number of Afghan journalists who would appear to be prime candidates for the scheme but help has not been forthcoming. Other governments, including those of Germany, France and even Kosovo, have offered safe refuge to a number of journalists but the UK is failing in its obligations.

There remains a large number of journalists, particularly women, who remain in the country or have made it across the border to the seeming safety of Pakistan only to continue to face threats.

The Afghanistan Journalists’ Support Organization reported on 3 February that a number of Afghan journalists had been arrested in the Pakistani capital Islamabad. According to the report, phones, laptops, cameras, and other electronic and personal devices of journalists have been seized and inspected. Those arrested have passports and visas and are legally residing in Pakistan. They were later released but one Afghan journlaist said that the behavour of the Pakistani police towards those fleeing the Taliban was “insulting and wrong”.

As well as arrest, journalists fleeing Afghanistan to Pakistan face other problems. One female journalist, who was forced to leave Afghanistan for fear of retribution by the Taliban, has shared her shocking story with Index below.

—

“I am a young Afghan broadcast journalist with almost five years of experience in the field. I have worked as a news anchor, presenter and reporter during the course of my career, and I have been associated with a nunebr of renowned media organisations in Afghanistan.

“Due to my work as a journalist, I have confronted many things from house raids, serious threats, online bullying, digital and cyber-attacks and harassment. I had received several threats from the Taliban before their rise to power, my Facebook account was hacked twice, I had to change my mobile number multiple times due to threats and harassment.

“After the takeover of Kabul, the Taliban launched a crackdown on the media and raids on the houses of the journalists started. Understanding the severity of the situation I tried to flee the country multiple times straight after their takeover, but due to closure of borders I didn’t succeed. I had to go into hiding and luckily I narrowly escaped a day before the raid of my house by the Taliban. I travelled in burqa with my elder brother to a location in the north east of the country where I stayed here for a month and a half with some of my distant relatives before fleeing clandestinely to Pakistan after borders were opened in October 2021.

“Since then, I have been living alone in Pakistan away from my family and loved ones with no job and livelihood. I have faced and I am still facing a plethora of issues here in Pakistan.

“I have been forced to live in unhygienic slums due to financial issues. I have spent many days without food and when I do eat, it is often just once a day. I have been ill many times, but I haven’t been to hospital or received any medication, and have been suffering from mental health issues like anxiety, depression, insomnia, and stress. I haven’t been able to purchase clothes for myself since I fled Afghanistan.

“I have also been a victim of discrimination and racism due to my ethnicity, nationality and religion. I was kicked out of two dormitories due to my nationality and ethnicity and also faced harassment and discrimination. In two places I have stayed my money was taken as a deposit before allowing me to live in the apartment as a tenant, but in both of these places my money was not returned when leaving.

“I have struggled to meet even my most basic needs, but support from Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and Frontline Defenders (FLD) has given me some respite and these funds have enabled me to survive.

“During this period, I have gone through hell – Pakistan is little different to Afghanistan. Here too there are Taliban sympathisers. There is no safety, no job opportunities, inflation is high. There is much discrimination, racism and prejudice in the society and there is hostility towards Afghan people in general and women in particular.

“A particularly unpleasant incident happened some months ago. One evening in July last year I was assaulted by an unknown biker while returning from the supermarket. The biker grabbed me and groped my body and was trying to pull me down to sexually assault me. But luckily this happened in the street near my flat, where I shouted loudly and, after a lot of pushing and shoving, I was able to escape. After this incident, I am scared to go out even during the day. Harassment in the streets for women is very normal here. I have to endure shameful touching, gazes and catcalls in public when I go out for anything and unfortunately, being Afghan, we can’t do anything about it.

“Now my situation is getting worse due to the long wait to relocate to a safe country. Moreover, the Pakistani authorities have put more restrictions on visas for Afghani people now, as the majority of visas are either denied or there are long delays. There is a clear reluctance from the government to issue visas to Afghans. I was on a one year visa to Pakistan which expired in the month of August 2022. I applied for a visa extension in the previous June 2022 but I have not received a decision yet. If the visa request is rejected I will be liable to pay heavy fines ($500) and face other legal liabilities. In December 2022, the Pakistani authorities announced that any Afghan without any valid visa will be arrested and put into prison for three years or deported back to Afghanistan.”

“I know of one Afghani family who were put in jail by the Pakistani authorities due to illegal overstay, where the male guardian of the family died in the jail – the rest of the family is still in jail. We all are really scared and fearful about this matter because we can’t afford any legal and financial liability or penalty at this stage. We also can’t go back to our country due to the severity of the threats to our life and safety and a really uncertain and dark future for women.”

“I am asking for assistance in relocating to any safe country where I could continue my journalism safely, complete my education and work to support myself and my family. In addition to serious threats for my life there is no future back home for women right now. There is a ban on education for women, a ban on women working in the media and NGOs and a ban on free movement of women outside without the veil and a male guardian. As a human being I also deserve the right to life, safety, education, and work. I deserve the freedom of movement and the freedom of expression, which are being denied and suppressed under the tyrannical and oppressive regime of Taliban. I am desperately and anxiously looking for any help in this regard and assistance with the financial support to meet my immediate and basic needs.

“I hope my plea will be heard and heeded in the right corners and a hand of support will be extended.”

06 Feb 23 | FEATURED: Jemimah Steinfield, News and features

Joshua Wong, Benny Tsai, Claudia Mo, Au Nok-hin, Ray Chan, Tat Cheng, Sam Cheung, Andrew Chiu, Owen Chow, Eddie Chu, Andy Chui, Ben Chung, Gary Fan, Frankie Fung, Kalvin Ho, Gwyneth Ho, Kwok Ka-ki, Lam Cheuk-ting, Mike Lam, Nathan Lau, Lawrence Lau, Ventus Lau, Shun Lee, Fergus Leung, Leung Kwok-hung, Kinda Li, Hendrick Lui, Gordon Ng, Ng Kin-wai, Carol Ng, Ricky Or, Michael Pang, Jimmy Sham, Lester Shum, Sze Tak-loy, Roy Tam, Jeremy Tam, Tam Tak-chi, Andrew Wan, Prince Wong, Henry Wong, Helena Wong, Wu Chi-wai, Alvin Yeung, Clarisse Yeung, Winnie Yu, Tiffany Yuen.

These are the names of all 47 people appearing in court today in Hong Kong. Remember their names. They are all people with families, people who had dreams and ambitions that were curtailed as Hong Kong went from being one of Asia’s most liberal cities to a tightly controlled state in just a matter of years. Amongst them are former politicians, democracy leaders, scholars, health care workers, even a disability activist. These people are the best of us and we could be them tomorrow. Rights are fragile – their examples are case in point.

The 47 are accused of “conspiracy to commit subversion” over the holding of unofficial pre-election primaries in July 2020. The primaries aimed to select the strongest candidates among Hong Kong’s then robust pro-democracy movement to run against the CCP-aligned parties. Until then, unofficial primary polls had been a common feature in Hong Kong political landscape, but in the wake of the draconian National Security Law which was passed at the end of June that year, Beijing labelled the democracy camp’s event illegal. In dawn raids on 6 January 2021, the organisers, candidates and campaigners were arrested. Many have been in jail since, denied bail.

The Hong Kong government labels them dangerous criminals and for that they could be behind bars for anything from three years to their whole lives. They are anything but.

The trial is a sham. There is no jury, going against a long tradition in Hong Kong’s legal system, which was established in line with British common law. The judges are handpicked by Beijing. There are reports that some who are taking up the 39 seats reserved for the public in the main courtroom don’t even know who is on trial.

The 47 are walking into court with their guilt presumed. Twenty-nine have already pleaded guilty. With no faith in the legal system, their only hope is a more lenient sentence. Ex-district councillor Ng Kin-wai told the three judges: “I did not succeed in subverting the state power. I plead guilty.” That he kowtowed is understandable; that a minority will not is a sign of how remarkable and resilient these people are. Former legislator Leung Kwok-hung said that there was “no crime to admit” while reiterating his not guilty plea.

This is a show trial masquerading as justice. It is a joke. But to laugh at this brings trouble too. Judge Andrew Chan told members of the public to “respect” the hearing after several jeered at the guilty pleas.

Outside court police presence is heavy. Dissent is being weeded out. Members of the League of Social Democrats, which is one of Hong Kong’s last active pro-democracy groups, turned up to protest and were reportedly pushed away. The chairperson of the group, Chan Po-ying, said “[I] hope reporters are all filming this” as police officers shoved her.

Fortunately reporters are there and are covering it. Hong Kong Free Press, for example, will be running regular on-the-ground updates – follow them here. This is not an easy landscape to operate in. According to reports, some people have warned others against speaking to the press, while journalists have been filmed and photographed by onlookers.

We are on day one of the trial. It is expected to last 90 days, with sentencing to follow after. Alongside Jimmy Lai’s trial – now postponed to the Autumn – it is the biggest and most important trial Hong Kong has seen in years, if not decades. And yet visit a Chinese or Hong Kong-run newspaper and it is buried under other news, if it’s reported at all. They want to forget them. We won’t allow that. Remember their names; better still, say their names out-loud.

We repeat – Joshua Wong, Benny Tsai, Claudia Mo, Au Nok-hin, Ray Chan, Tat Cheng, Sam Cheung, Andrew Chiu, Owen Chow, Eddie Chu, Andy Chui, Ben Chung, Gary Fan, Frankie Fung, Kalvin Ho, Gwyneth Ho, Kwok Ka-ki, Lam Cheuk-ting, Mike Lam, Nathan Lau, Lawrence Lau, Ventus Lau, Shun Lee, Fergus Leung, Leung Kwok-hung, Kinda Li, Hendrick Lui, Gordon Ng, Ng Kin-wai, Carol Ng, Ricky Or, Michael Pang, Jimmy Sham, Lester Shum, Sze Tak-loy, Roy Tam, Jeremy Tam, Tam Tak-chi, Andrew Wan, Prince Wong, Henry Wong, Helena Wong, Wu Chi-wai, Alvin Yeung, Clarisse Yeung, Winnie Yu, Tiffany Yuen.

03 Feb 23 | Opinion, Ruth's blog, United Kingdom

Photo: Tookapic/Pixabay

After seven years of debate, five Secretaries of State and hours and hours of parliamentary discussion the Online Safety Bill has reached the second chamber of the British legislature. In the coming months new language will be negotiated, legislative clauses ironed out and deals will be done with the government to get it over the line. But the question for Index is what will be the final impact of the legislation on freedom of expression and how will we know how much content is being deleted as a matter of course.

The team at Index have been working, with partners, for several years to try and ensure that freedom of expression online is protected within the legislation. That the unintended consequences of the bill don’t impinge our rights to debate, argue, inspire and even dismiss each other on the online platforms which are now fundamental to many of our daily lives. After all, in a post Covid world, many of us don’t differentiate between time spent online and time spent in real life. They are typically one and the same. That isn’t to say however that as a society we have managed to establish social norms online (as we have offline) which allow the majority of us to go about our daily lives without unnecessary conflict and pain.

We’ve been working so intently on this bill not just because we want to protect digital rights in the UK but because this legislation is likely to set a global standard. So restrictions on speech in this legislation will give cover to tyrants and bad faith actors around the world who seek to use some aspects of this new law to impinge on the free expression of their own populations. Which is why our work on this bill is so important.

We still have two main concerns about the legislation in its current format. The first is the definition, identification and deletion of illegal content. The legislation currently demands that the platforms determine what is illegal and then automatically delete the content so it can’t be seen, shared or amplified. In theory that sounds completely reasonable, but given the sheer scale of content on social media platforms these determinations will have to be made by algorithms not people. And as we know algorithms have built-in bias and they struggle to identify nuance, satire or context. That’s even more the case when the language isn’t English or the content is imagery rather than words. When you add in the concept of corporate fines and executive prosecution it’s likely that most platforms will opt to over-delete rather than potentially fall foul of the new regulatory regime. Content that contains certain keywords, phrases, or images are likely to be deleted by default – even if the context is the opposite of their normal use. The unintended consequence of seeking to automatically delete content without providing platforms with a liability shield so they can retain the posts without being criminally liable will lead to mass over-deletion.

The second significant concern are the proposals to break end-to-end encryption. The government claim that this would only be for finding evidence of child abuse, which again sounds reasonable. But end-to-end encryption cannot be a halfway house. Something is either encrypted to ensure privacy or it isn’t and therefore can be hacked. And whilst no one would or should defend those who use such tools to hurt children, we need to consider how else the tools are used. By dissidents to tell their stories, by journalists to protect their sources, by families to share children’s photos, by banks and online retailers to keep us financially protected and by victims of domestic violence to plan their escape. This is not a simple tool which can be broken at whim, we need to find a way to make sure that everyone is protected while we seek to protect children from child abusers. This cannot be beyond the wit of our legislators and in the coming months we’ll find out.

01 Feb 23 | Iran, News and features

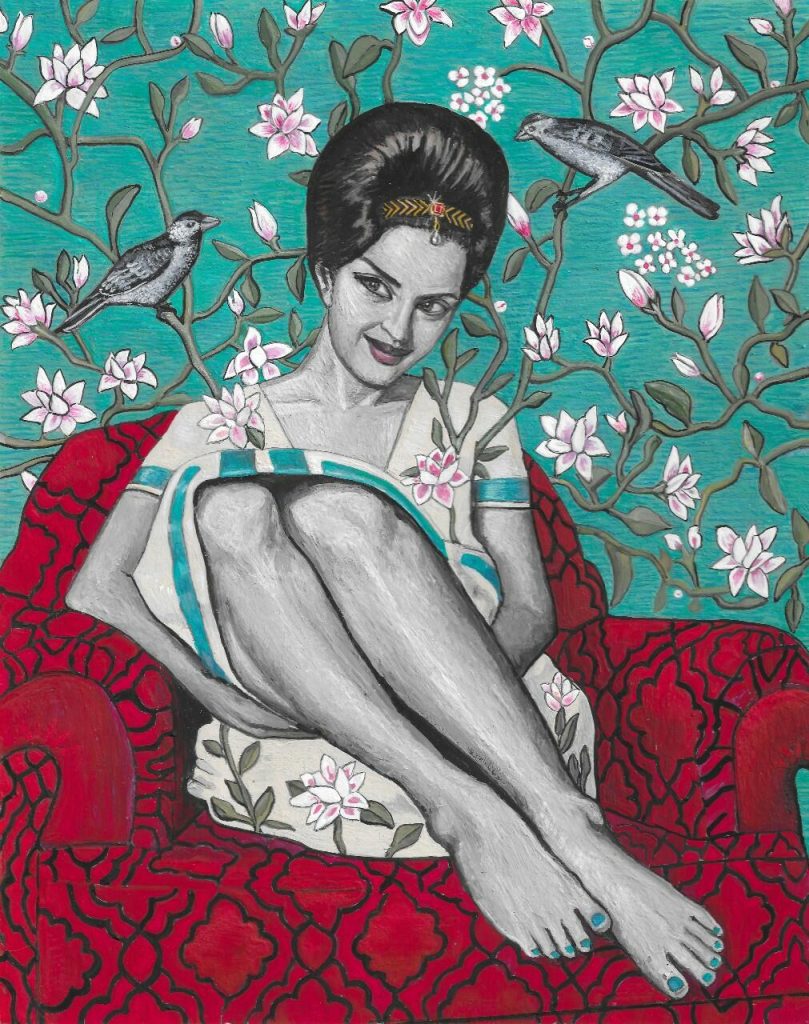

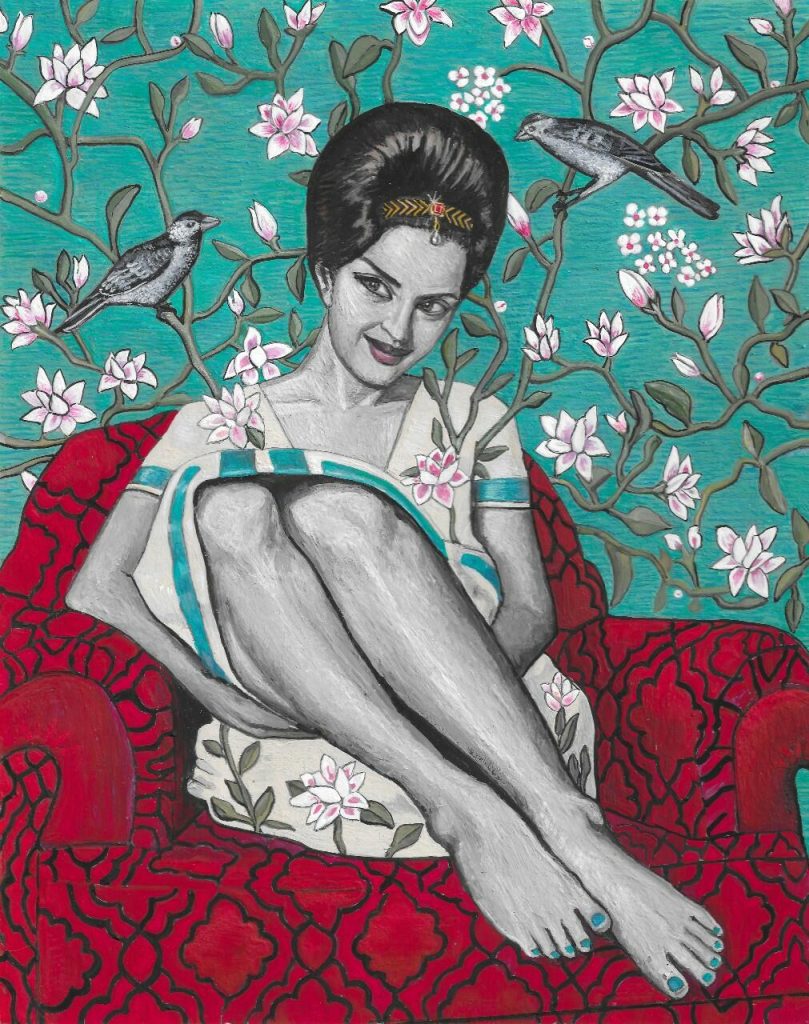

Wild at Heart (Portrait of Pouran Shapoori), 2019 Credit: Soheila Sokhanvari, courtesy Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

The long, winding path of The Curve art gallery at London’s Barbican Centre has been transformed into a devotional space. The cavernous room is dimly lit and echoes with the calming voices of female Iranian singers. Sprawling, Islamic, geometric patterns roll down the tall walls which are splintered with the light projected onto them by dazzling mirrored sculptures. Apart from the female voices, it feels like a mosque.

Take a closer look, and the walls are scattered with traditional Persian miniatures, depicting women whose histories have been erased in Iran. In painstaking detail, Soheila Sokhanvari’s portraits provide a snapshot into women’s lives pre-revolution. Born in Shiraz in the Fars Province of Iran, she came to England in 1978, just a year before the Islamic Revolution. But Sokhanvari remains enchanted with the country she left behind. Her miniatures depict unveiled and glamorous women, creative dissidents who pursued careers in a country awash with Western style but not its freedoms.

“I can relate directly to the women in my paintings,” she told Index. “Like them I am an artist but, unlike them, I am able to pursue my career, wear what I want and act as I want, and the idea that one day someone could take my freedom away from me is unthinkable”.

The portraits are displayed without names or biographical info but, by scanning a QR code, we are guided through the exhibition by their stories. There are 28 in total: actors, singers, poets, writers, dancers and film directors, all of which were either forced into silence or exile in 1979, when the Islamic Revolution led to a rollback in women’s legal rights. Much of their work is censored in Iran today. “I knew of many of the women from my own experience and time in Iran as a young girl,” Sokhanvari explained. “They were my idols, but finding out more information about the lives of several of the women took lots of research – they were essentially erased from the record by the regime”. She said that a small number of the women – like singer and actress Googoosh – are very famous, but that several had tragically died too young and were hard to trace.

The exhibition draws the spotlight back onto these talented women for which, she says, she feels a deep loss. The portraits beautifully capture this feeling: a simultaneous celebration of their bravery and a mourning of their freedoms. Vivid patterns and clothing contrast monochromatic faces, which make the pictures feel both vibrant and ghostly. The use of new and old multimedia was significant in telling these stories too. “I painted my portraits in the ancient technique of egg tempera, onto calf vellum, and I included films in which the women starred, ” Sokhanvari said. Two holograms of dancing Iranian actors Kobra Saeedi and Jamileh are also hidden in boxes. “I wanted the viewers to see these women, to watch them dance and to hear them sing, since they have been banned from these platforms.” The broadcasting of women’s voices in public is illegal in Iran. “I wanted to show these women at the height of their creativity, to show them as the sensational artists that they are, and using multimedia helped to achieve this immersive experience.”

This contrast of old and new is fitting. While the exhibition was curated without sight of the current unrest in Iran, the portraits certainly gain a tragic poignancy because of it. The brave women of Sokhanvari’s portraits embody much of what people are fighting for today. “Young women are at the front of this revolution and that is what gives it its power,” she told Index. “I feel a new sense of positivity and hope that perhaps we will see the end of this regime, but simultaneously I feel pain and bitterness that it is at the cost of so many bright lives.”

Although she doesn’t describe her artwork as a protest, she says that the message is political.

“What is happening in Iran can no longer be seen as just another protest, it is a revolution and I stand in solidarity with my sisters.” I asked if her portraits reflect a lost past or a hopeful future. She says both.

‘Rebel Rebel’ at The Curve, Barbican is open until 26 February 2023

31 Jan 23 | Burma, FEATURED: Katie Dancey-Downes, News and features

This year’s planned elections in Myanmar were always going to be controversial. Then, last week, the military junta that runs the country announced new laws which will create yet more hurdles for democracy. Political parties must re-register within 60 days and sign up at least 100,000 members. Those that the military-controlled government deems to be connected with terrorist groups or to be unlawful will not be allowed to form.

Two years on from the 2021 military coup, Burmese journalist Wai Moe remembers seeing military fighters in the city of Yangon.

“Many of my friends, they did not believe there would be a coup, but I already believed this,” he told Index.

On the morning of 1 February 2021, the phone rang. A friend told Moe that the country’s leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, had been arrested. That night, he remembers the military announcement that due to the emergency situation, power was being given to the commander-in-chief, General Min Aung Hlaing.

“I learnt about the coup… I was very afraid,” Moe said. “I thought, ‘They’re going to arrest me.’”

He wasn’t arrested that day, but when in April he was offered the opportunity to flee the country on a chartered plane, he took it.

Moe is now in exile from Myanmar for the second time in his life. The first occasion came after his release from a five-year-stint as a political prisoner in the mid-1990s. He said he had been part of an underground organisation that secretly studied politics and history.

He still speaks to people in Myanmar, some of whom he describes as going back to normal life after the recent lifting of the curfew. They visit bars and nightclubs. “Day by day, they are in control,” he said of the military, believing the curfew lift to be a sign of this.

The changing face of the protest movement

“When the coup occurred, what initially came out of that was a large-scale protest resistance,” Dan Anlezark, the deputy head of investigations at Myanmar Witness, told Index. This Burmese-led organisation formed in March 2021 in response to events that unfolded following the coup. The group identifies and verifies potential human rights abuses to promote accountability in Myanmar, often using videos and testimonies posted on Facebook and other digital platforms.

Following the protests came violent crackdowns.

Student Thu Thu Zin marched at the front of a small anti-coup protest in Mandalay on 27 July 2021, taking one end of the red Mya Taung Strike Front flag and chanting. According to the evidence verified by Myanmar Witness, the 25-year-old was shot and killed. There was nothing to suggest Zin or the protesters had been violent. Zin’s body was removed, sand used to conceal the blood and her body placed into the back of a truck and taken away. Her family found out about her death when they saw photos of her body on social media. The report concludes that the shooting can, with reasonable certainty, be attributed to the military.

“She became quite symbolic of the protest movement at the start, of that resistance and how forcefully it was met,” Anlezark said.

Since that time, the landscape has changed.

“Once the protesters saw exactly how much force they were being met with, those protests died down. If you’re being met with a gun, and you know that they’re willing to use it, it’s not the most effective means of resistance,” he said. Any protests that are still happening tend to be smaller and reactions to specific events.

Now there is an armed struggle for democracy, as a network of civilian groups, named the People’s Defence Force, clashes with the military. Meanwhile, military junta vehicle convoys are intentionally burning down villages at an alarming rate, according to evidence seen by Myanmar Witness.

Putting the horror of this situation into context, Anlezark explained that they have been examining evidence of burned bodies, found shackled.

“The why is always hard to answer,” he said. “It does look to be that the villages have a link to say PDF [People’s Defence Force] operations or there’s a PDF base nearby, or it’s seen in the eyes of the SAC [State Administration Council] as a means of potential intimidation. Or just to scare the living daylights out of people.”

Erin Michalak has a background in forensic science and now works largely with the arms team at Myanmar Witness. She explained that an increase in unguided airstrikes comes hand-in-hand with the SAC having more aircrafts available to them. Air assets have been transferred from countries including Russia. For some areas in Myanmar, access through ground troops has proven difficult, but airstrikes have made these places potential targets.

“Commentary that I see and that I hear is that the air strikes are almost a symptom of the SAC knowing that they’re not winning or that they’re not progressing how they would like in a ground war,” Anlezark said.

The vanishing Myanmar media

“On 8 March, they banned all the private publications,” Moe told Index, explaining that any continuing news outlets became state controlled. After five publications initially had their licences revoked, the rest fell victim shortly after.

Some citizens turned to foreign radio, like the BBC and Radio Free Asia, and accessed international news through VPNs, Moe explained. Facebook was banned in the early days of the coup, but it is still used extensively to share information, as is the messaging app Telegram.

“If they [media] were pro-democracy or anti-regime, it was shut down or there was a sense that there was going to be something negative that occurred,” Michalak said. “And there are reports and claims of journalists being detained and imprisoned within Myanmar — these are harder to verify.”

In addition, she described evidence of some prisons acting without proper court systems and performing their own sentencing.

“It’s really hard to get an understanding of what’s truly going on here,” she said. “But there is evidence that there has been a negative effect on journalism and freedom of speech within the country.”

In January this year, the military junta released hundreds of political prisoners in celebration of Myanmar’s 75th anniversary of independence. While welcome news to those released, thousands remain behind bars, including former leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, who will likely spend the rest of her life in prison and Htien Lin, an artist and Index contributor who was arrested last August.

“It did appear to be very political, with international viewership noticing that they were releasing these prisoners,” Michalak said.

She described how most of the sentences were connected to freedom of speech and expressing disagreement with the regime. Holding high-profile figures for longer would have been difficult for the military, she said.

Myanmar’s military administration has claimed it will run a general election in August 2023, coinciding with the end of the state of emergency.

“We will be very closely monitoring that to identify voter coercion, disenfranchisement, fraud and violence, which is almost certainly going to occur against protesters and people trying to cast a democratic vote,” Anlezark said.

Moe does not see how any proposed elections could be free and fair.

“There is no space for media, no space for press freedom,” he said. “They are only looking for legitimacy.”

In the run up, the military is conducting a nationwide census, and the reasons for it are unclear. The information in the hands of the junta, Anlezark said, could become a targeting list. It might show who is still in the country, who should be and who might have disappeared to join the network of armed civilian groups who have training camps in the jungle. Daily allegations on Facebook claim that census officials are going from town to town and checking their lists. Myanmar Witness is monitoring and collecting the information.

As to the future of the country, from which he is again exiled, Moe said: “We have to find a way out of the crisis.”

30 Jan 23 | Brazil, News and features

The images of that fateful day, 8 January 2023, are still vivid in my mind. It was Sunday, I was at my house in Porto Alegre, a city in southern Brazil, and I turned on the TV live as usual. The scenes I saw on CNN were ones of barbarism and destruction at the Three Powers Plaza, in Brasília. While watching the images of the police allowing a free passage to the horde of Jair Bolsonaro supporters, I felt fear and outrage. They destroyed all the buildings of the National Congress, the Federal Supreme Court and the president’s house, the Planalto Palace.

According to Alexandre de Moraes, Minister of the Supreme Court Federal (STF), at least 140 of the 1,500 Bolsonaristas arrested for the attacks are accused of terrorist acts, criminal association and threat and incitement of violence. For Moraes, the crimes are “very serious” and were committed “evidently out of step with the guarantee of freedom of expression”, provided for in Article 5 of the Constitution.

But it is precisely freedom of expression that Bolsonaristas claim as an argument for – and justification of – their dissemination of hate speech and fake news, acts of racism or any type of violent action. And now, after the arrests of the perpetrators of the attacks in Brasília, they claim to be victims of “censorship”.

In the days leading up to the attacks, inflammatory rhetoric intensified on social media and included a series of thinly veiled metaphors. The main one was an invitation to “Selma’s Party”.

“Selma” is a play on the word selva, which means jungle in Portuguese, and is also used by the Brazilian military as a greeting or war cry. This vocabulary is the result of long exposure to a sea of fake news broadcast on Bolsonarist’s profiles and channels, especially on WhatsApp, Telegram, YouTube and Twitter, always in the name of “God, homeland and family” – that’s why they self-styled as “patriots”. The daily gaslighting is also promoted via TV channels, radio and Jair Bolsonaro himself, who has long been raising doubts about the electoral process and promoting the cult of violence and destruction of the “enemy”.

It became so serious that even I began to worry about what would happen on 31 October 2022, the day of the elections: social media posts said that anyone who voted for Lula would be identified by their hair or the colour of their clothes and would die. (Those who are Bolsonaristas usually wear the shirts of the Brazilian soccer team.)

The result of this social media intoxication is a subsect of people who are detached from reality: of these some think that the elections were rigged by the STF, that Lula is dead and the person in his place is a double, that Brazil will become a communist country. They even prayed collectively to be saved by extraterrestrials and, of course, said that the attacks in Brasília were carried out by “infiltrators of the left”. It’s a collective psychosis.

By inverting rational logic, the Bolsonarist discourse sounds like a delirium, and it is tempting to classify it in the realm of the ridiculous. But the concrete results of the denial of reality and the proclamation of hatred have now come to fruition.

Today, by saying they’ve been censored, the Bolsonarist camp is basically calling for revenge. They say they are victims of political persecution and that the Lula government and the STF are disrespecting the Constitution, which, by the way, had copies stolen and torn in the attacks. They’ve been led down an even darker path, saying that Brazil is living under a dictatorship. Censorship, whether real or imaginary, has become a useful tool for a Bolsonarist who wants to continue promoting chaos.

That said, the response to the attacks has been troubling. On the surface, it seems reasonable for the STF to repress disinformation and suspend profiles on social networks, even more so now, after the attacks. The justification for suspending Bolsonarist profiles has a legal basis in the Civil Rights Framework for the Internet (Law 12,965/2014).

In addition to suspending profiles, the STF and the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) have ordered the removal of posts (especially on Twitter) that attack democracy and spread conspiracy theories. Among them was the influencer “Monark” (1.4 million followers) and Nikolas Ferreira, a federal representative from the state of Minas Gerais, with two million followers, both of whom were suspended from Twitter for their perceived role in the coup.

There is also the “Democracy Package”, launched on 26 January. It is a series of measures prepared by the Minister of Justice, Flavio Dino, including the regulation of social networking platforms to curb “political crimes” and ban content judged undemocratic. It is not yet known what the criteria will be, but it is clearly a proposal to limit freedom of expression and the plurality of speech online. This set of measures will be sent to the National Congress for a vote.

On the surface reasonable yes, but in reality the “deplatforming” is dangerous because it already serves as a basis for the extreme right to say they are being persecuted and censored, and this gives even more fuel for a violent civil insurrection with military support. Also where will it end? Where is the line?

Of course it’s not easy to decide the limits of free expression at this moment. Still, have authorities got the balance right? Since the end of the dictatorship in 1985, I’ve never come across such a fine line between liberty and punishment, as well as surveillance on social media – and I fear where it will lead.

On 12 December, 2022, the date of Lula’s inauguration as president-elect, hundreds of Bolsonaristas promoted a riot in Brasília, culminating in the invasion of the Federal Police building and burning of vehicles, including several buses, one of them hanging on the side of an overpass where traffic was flowing. Then, on 24 December 2022, a truck loaded with explosives was located near Brasília airport. The man behind the truck bomb confessed to being a Bolsonarist and said the act was planned by a group that had been camped in front of the Army General Headquarters for more than two months.

The military has been accused of assisting in the execution of plans by the far right. Even President Lula himself claimed that there was “evidence” of collusion between them and Bolsonaro’s supporters.

If you say this to a Bolsonarist though he will laugh in your face and say it’s all a lie from the media. He will believe that the people dressed in green and yellow in Brasilia, on 8 January 2023, were members of the left who wanted to carry out a “self-coup” days after being victorious in the elections in a pledge to crack down on Bolsonaro supporters.

This is the abyss Brazil has plunged into since Bolsonaro lost the election. On top of refusing to accept defeat, he has sought refuge in the United States since 29 December 2022, maintaining a strategic and deliberate silence for his supporters. Meanwhile, faced with immense challenges – maintaining democratic values while punishing those who broke the law – Lula finds himself walking in cotton shoes on glass. It’s hard work and the events of early January are not over yet.

27 Jan 23 | Germany, Opinion, Poland, Ruth's blog

The theme of Holocaust Memorial Day this year is ordinary people. Words have power and their meaning changes with context – and in the context of the Holocaust the word ordinary is one that brings conflicted emotions. Those killed were indeed ordinary people who happened to be different, Jewish, gay, Roma, disabled, trade unionists and political dissenters. Many of those that killed them probably started as ordinary people who believed the propaganda that inspired hate and murder. Those that intervened to save them were ordinary people with an incredible value set that demanded in many cases that they risked their lives to save people that they barely knew.

In the run up to Holocaust Memorial Day I had the privilege of hearing the testimony of Janine Webber, a Holocaust survivor who lost huge swathes of her family. There is nothing quite so stark and shocking as hearing first-hand the stories of those people who were confronted with the ultimate evil. Janine survived the ghetto and was hidden and betrayed several times, eventually finding sanctuary in a convent and then with an elderly Polish family. She was saved by ordinary people and betrayed by ordinary people and before this happened to her she was an ordinary little girl in Poland. But in the course of four years she lost her parents, her brother and all of her extended family – the only other surviving members of her family were her aunt and an uncle. Her story will stay with me – and everyone else who heard her testimony – for as long as we live.

The question that has stuck with me since I had the privilege of listening to Janine, is what happens when she is sadly no longer with us. When the survivors are no longer with us to challenge those people who seek to deny or distort the facts of the Holocaust? The onus is on all of us to tell their stories and to shine a light on the lies and misinformation spouted by political extremists who seek to use one of the worst chapters in human history as a political football.

Last week the British House of Lords held its first debate to mark Holocaust Memorial Day. As a new member of the Lords, it was my privilege and responsibility to contribute to the debate. You can read my speech here.

Speaking about such an important topic in a national legislature is not something that anyone would or should take lightly, it was politics at its best – informed, considered and heartfelt.

The debate has made me think repeatedly about the fundamental importance of our core human rights and how we have to cherish and protect them. I can write this blog today because I have a guaranteed right, under British law, to express myself and articulate my opinions. Tyrants and dictators, always, as one of their earliest actions, seek to restrict a free media, undermine academic freedoms, remove books from libraries, and silence their critics. Index exists to provide a platform to those being silenced and we always will – but we also provide a voice to those who seek to tell truth to power, who seek to challenge misinformation, who stand against tyranny. We have for the last fifty years and we will for the next fifty.

27 Jan 23 | Belarus, FEATURED: Mark Frary, News and features

Today marks the 45th birthday of our former Index colleague Andrei Aliaksandrau. Sadly, he will not be spending it with his family, opening presents and eating cake. Instead he is in prison, serving a 14-year prison sentence handed down by the Minsk Regional Court for “grossly violating public order”, “creation of an extremist formation” and, most severely of all, “high treason”. Of course, when you are in an authoritarian regime, such charges mean nothing.

Andrei has been in the SIZO-2 pre-detention centre in Vitsebsk for just over two years now. Vitsebsk, in north-eastern Belarus is the birthplace of artist Marc Chagall. Now it is becoming better known for holding political prisoners.

A British detainee who was held in the same centre said conditions were “disastrous”. Travel agent Alan Smith was held in a cell measuring four metres by two with five other prisoners: his alleged crime – helping Iraqis illegally enter Belarus.

“Windows were closed, [there was] no ventilation, people smoke there [and] the toilet is open,” he told the independent media channel Charter 97. He added that there were informants in every cell and they were monitored with cameras and microphones and warned not to talk about “business matters” i.e. why they were in detention.

Andrei’s father visited him in Vitsebsk just over two weeks ago. He told friends, “I was met by a gaunt-looking Andrei, with very short hair, but full of energy.” Despite everything, his father said he was in “a good moral and psychological condition”.

Andrei’s wife, Irina Zlobina, was previously a florist

Andrei was not even allowed to leave the detention centre to marry his fiancee Irina Zlobina last September.

Irina is a graduate of the faculty of philosophy and social sciences of the Belarusian State University and in recent years had been running her own small business of selling flowers and souvenirs. She was arrested and tried at the same time as Andrei and was sentenced to nine years in prison, again for “grossly violating public order” and “high treason”.

The only time the couple have seen each other since they were arrested is at their trial, in the so-called BelaPAN case, alongside the former news agency’s editor-in-chief and director Irina Levshina, who got four years in prison, and former director of the agency Dmitry Novozhilov, who got six years.

Before the trial, Irina was at a pre-detention centre in Homel in south-eastern Belarus; she has now been moved to a penal colony in the city.

Now Andrei is also on the move and he has been taken on a 115-kilometre journey to penal colony no.1 in Navapolack where he will serve out the rest of his sentence.

We asked some of Andrei’s friends for their birthday wishes for him, even though he may never see their thoughts and comments.

Joanna Szymanska, senior programme officer at ARTICLE 19, where Andrei also worked while he was in the UK, says wistfully, “It’s another birthday that Andrei will spend behind bars.”

“I have lots of good memories related to Andrei, he’s always been the life of the party. I especially miss our long discussions about Depeche Mode, we’re both huge fans and Andrei has a great voice, I can still hear him singing his favourite songs,” she says.

“I sometimes wonder, does he still sing them? I haven’t received a letter from him in a long time, many letters are not delivered to political prisoners, especially if they are sent from abroad. But I’m sure Andrei stays strong and he knows the world hasn’t forgotten. Andrei, your friends are with you.”

Andrei Bastunets, chair of the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), says he met Andrei in the early 2000s: “We were united by many things: football, poetry and, of course, journalism. No, not ‘were united’, but ‘are united’. Even though he’s in prison and I’m abroad. We are united despite the fact that, it seems, my letters to Andrei do not reach him. Prison censors don’t let them through to political prisoners. I don’t think he’ll get my birthday greetings now. And not only mine, but a lot of birthday greetings. He has a lot of friends and he has been and remains a good friend – witty, charismatic, courageous.”

He says, “Once, back in the days when letters to political prisoners and their responses were still reaching their recipients, he wrote to me: ‘I now ‘listen’ to my friends’ letters, guessing vibes and intonations – a personal ‘radio’. My own Radio Liberty. My personal ‘free speech’. Thanks for that to everyone who writes to me. We all are one big independent media outlet now. A blog of those who refuse to despair.”

“In another letter – this time about football (although we follow different teams) – he wrote: ‘Somehow there was a reason to mumble the Liverpool’s anthem, You’ll Never Walk Alone. Supportive words from the letters made me ‘sing it’, playing it on my internal radio, drowning out the external Russkoye Radio. It got to the point where I caught myself thrumming the club anthem in Belarusian. It came out a bit pathetic – but it’s an anthem, just my translation (don’t shoot the pianist). But somehow it seemed somehow in tune with, I don’t know, with the moment, the feeling, the mood.”

Even if you may not get to read this Andrei, you’ll never walk alone.

What can Index readers do? Please join our joint campaign with ARTICLE19, share the message and sign the petition. You can also befriend Andrei and Irina via our partners at Politzek.

27 Jan 23 | FEATURED: Martin Bright, Index Arts, News and features, Russia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Uzbekistan

The title of the play Crimea, 5am refers to the time in the morning the authorities choose to raid the homes of activists in the Russian-occupied territory. It is a time of fear and horror for the Crimean Tatars whose voices make up the text of this verbatim play, taken from the testimonies of the men now held in Putin’s prisons and the families waiting at home for them.

Crimea 5am brings to life one of the lesser-known aspects of the brutal war in Ukraine, which began not in February 2022 but in March 2014. It draws on the oral history of the suppression of the Tatar Muslim minority, who returned to the peninsula in the 1990s following independence after years of exile from their homeland.

Much of what we know of life in Crimea since 2014 has come from activists turned citizen journalists. This is one of the reasons the Russian authorities have cracked down so hard on Tatars, characterizing them either as political extremists or Islamist terrorists linked to the group Hizb-ut-Tahrir.

Two examples from the play show how ordinary Tatars went from being activists, to journalists to dissidents in the face of Russian repression.

Tymur Ibrahimov, 38, moved back to Crimea from Uzbeksitan at the age of six in 1991 after the death of his father. In the play, his wife Diliara, explains his transformation from computer repairman to enemy of the state: “It used to be different, until 2014, you know, back then he would make home videos, he would take pictures of nature, like, of the bees and butterflies on flowers, just like that. It all changed in 2015 and he began making footage of what was going on in Crimea. That is, all the searches, court hearings, “Crimean Solidarity” meetings.” For the crime of recording the resistance of his people Tymur was sentenced to 17 years in prison.

Narminan Memedeminov, 39, also moved back to Crimea from Uzbekistan in 1991. After graduating in economics he became involved in human rights activism and media coordinator for the Crimean Solidarity movement. “Here’s an example: I went and took a video of somebody helping out a prisoner’s family, like, basic stuff, they would take the child to the hospital, help them hang the wallpaper, fix the plumbing, send off the parcels to the detention centre and so on… And in the end, everybody involved was at risk: those who took videos, those who helped, those who did anything at all.”

Index editor at large Martin Bright (left) taking part in a post-play discussion.

The stories have been brought together by two Ukrainian writers, Natalia Vorozhbyt and Anastasiia Kosodii and the project is backed by the Ukrainian Institute and the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a way of bringing the situation to international attention. I had the privilege of watching a reading of of the play at the Kiln Theatre, Kilburn in London last week with professional actors alongside non-professional activists and supporters. Directed by Josephine Burton and produced by Dash Arts, the play focuses on the domestic lives of the families of the Tatar political prisoners and particularly the women.

Burton told Index that until the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Crimea has drifted from international attention. “Helped by a media blackout, we forgot that the peninsula has been occupied by Russians for almost nine years now and its Tatar community oppressed,” she said. “Determined to fight this silence, the community has relentlessly documented this oppression – filming and uploading searches, arrests and court cases of its people by the Russian Security Forces. And for this act, these “Citizen Journalists” have been arrested themselves and given insanely long sentences, some for up to 20 years in penal colonies.”

Crimea 5am focuses on the everyday lives of Tatar dissidents, drawn from many hours of recordings with the families of 11 political prisoners. “It builds a beautiful and powerful portrait of a community, ripped apart by this tragedy, but also woven with stories of love and resilience through the prism of the wives left behind. It is this mix of tenderness and humour alongside the unfathomable darkness which enables its impact. We the audience become invested in their lives and feel the impact of their tragedy deeply.”

Dash Arts is looking for further opportunities to perform Crimea 5am: https://www.dasharts.org.uk/