18 Nov 20 | News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115574″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]On 11 September, the peaceful silence of the early morning in Sürik, a tiny, unassuming village located in the barren yet beautiful mountains of Van, an eastern and mostly Kurdish populated province in Turkey, was broken by the sound of a violent explosion. The blast was so powerful that the earth shook; the adobe houses of the village rattled.

The Turkish military had been conducting operations in the region since early September, and clashes between soldiers and militants of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), an armed group which has been fighting for Kurdish independence for more than four decades, had been more frequent than usual. The villagers saw military helicopters circling the usually serene skies above Çatak.

By the time the sun had melted the previous night’s fragile frost, one of the choppers had landed in an area behind the village. They took off a while later, taking two of the villagers with them.

The two men, Osman Şiban, 50, and Server Turgut, 63, reappeared two days later, in the ward of a military hospital in Van. While these are nowhere near rare occurrences in the Turkish southeast, the country would have never heard about the horrific torture the two men went through if it wasn’t for a news report published on the day of their reappearance by Cemil Uğur, a Van-based journalist with the Mezopotamya News Agency (MA). The report claimed they were beaten and pushed off a helicopter.

The Van governor’s office denied the allegations of torture, saying the two villagers, captured as part of an operation in the region named Yıldırım-10 Norduz (after an indigenous mountain goat), ignored commands to stop.

In the following days, other reporters—Adnan Bilen, the Van bureau chief of MA, Şehriban Abi from the feminist Kurdish news agency JinNews and freelancer Nazan Sala—all known for reporting on human rights violations in Turkey’s Kurdish regions, followed the story, filling in the details, talking to the families and witnesses, gathering documents from forensic invesetigations and prosecutors.

An interview with Siban from his hospital bed by Uğur on 17 September featured a photo of Şiban, whose bloody eyes (top) left little to the imagination about the horrors the two men must have had undergone, whom the journalist talked with in his hospital bed.

On 30 September, Turgut died after days in intensive care.

Less than a week after Turgut’s death, the homes of the journalists reporting on the case were raided and, a few days later, they were arrested on charges of “membership of a terrorist organisation”.

Journalists punished for reporting the news

More details of the unspeakable torture the two men had gone through came out on 2 November, when independent lawmaker Ahmet Şik, who travelled to the region in late October, revealed the details of his investigation at a press conference in parliament.

The two men were beaten on the chopper, later, pushed off — presumably after it landed – and then beaten to near-death by 150 gendarmerie soldiers in scenes in a “state-sanctioned lynching.”

Şık’s report also detailed other ways in which the state attempted to cover up the torture of the two villagers in addition to arresting the people who reported on the case. He later told the Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA),whose lawyers represent three of the imprisoned Van reporters, that the journalists, who the authorities assert were detained on the basis of an investigation launched prior to the Van incident, were clearly being punished for their reporting on the ordeal of the two villagers.

A ‘grave danger’ for all journalists

Lawyer Veysel Ok, co-director of the MLSA, notes that this punishment for reporting the news has the power to have serious repercussions for other journalists in Turkey, where 86 journalists are in prison.

He points to several alarming developments regarding the investigation into the journalists, saying, “In the journalists’ arrest order, the court accused these journalists of ‘reporting on social incidents against the state but in favour of the terrorist organisation PKK/KCK’ in order to incite agitation, and ‘making news in a continuous way, with variety and in high numbers.’”

To highlight the gravity of the possible consequences, “these journalists are all Kurdish and have been working in the region, and specifically in Van, for a very long time.”

“Their reporting has always shed light on human rights violations against Kurdish citizens in the region,” Ok said.

The arrest warrant also accuses the journalists of “criticising and harming the reputation of the anti-terrorism effort of the Republic of Turkey”. Another accusation is “identifying oneself as a journalist and making news reports for a fee without being a press card holder”.

“So the court is arguing that the four reporters are not ‘real’ journalists on the grounds that they don’t have an official press card issued by the president’s office,” Ok said. “There is not a single line in the Turkish legislation that stipulates that one needs a press card to be a journalist. Press card accreditation is necessary only for following government officials’ activities and the practice has been, as of late, to only issue them to those journalists who work for the pro-government media, so this press card mention in the warrant can have far-reaching consequences for any journalist in Turkey.”

The justifications put forth by the court are “unacceptable,” the lawyer added.

“The judiciary aims to create a chilling effect on all journalists, like the Sword of Damocles,” he said. “That’s why we find this case extremely important, care about it deeply and demand solidarity from fellow journalists, and everyone who cares about freedom of speech and not just in Turkey but all around the world.”

Ok also noted another worrying problem about the case; that the prosecutor who is conducting the investigation against the Van journalists is the same one that conducts the investigation on the lynching of the two villagers.

“The arrest decision is a very alarming one for journalism,” he said. “This is why our organisation has taken on this case. We will take this unlawful arrest first to the Constitutional Court and then to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).”

Ok said he was in Van on 27 October where he visited the four journalists in prison and noted that although they seem to be in good spirits, they also demand solidarity and support from the outside world against the injustice they are suffering for doing their jobs.

“Van is a far-off city, in the easternmost part of the country,” Ok said. “It is important that this case is not forgotten because it is not in Istanbul. These journalists have written news reports that should win an award. We will be in Van at the time of the first hearing to support these journalists and their journalism. They deserve the support of their colleagues and rights groups everywhere for bringing out the truth.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Nov 20 | Europe and Central Asia, France, Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115559″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]In the last month, as the world has been preoccupied with the US elections and the ongoing ravages of the global pandemic, the people of France have turned on the news to learn of deadly terror attacks on their soil. Seemingly designed not just to murder and incite fear but as a direct attack on the core values of the French state.

In a Parisian suburb, Samuel Paty was beheaded by an extremist for teaching his students about the principle of free speech. In Nice, three people – Vincent Loques, Simone Barreto Silva and Nadine Devillers – were brutally murdered inside the ultimate sanctuary: a place of worship, the Notre-Dame basilica. Their ‘crime’? Attending church.

As ever in our interconnected world, a terror attack in one country has repercussions across the world and this has never been truer. Our choice of language and vocabulary when discussing such emotive issues can have untold consequences and when you combine the issues of national security, religion, extremism and politics, people rarely look beyond the headlines.

But it is unforgivable for national leaders to exploit the pain and anguish of others to promote their own world view and to shore up their own political standing. And beyond the pandemic that’s what we’ve seen. Rather than acknowledging the pain felt by the people of France and the fear that now lurks in many communities, not least French Muslims who now face a wave of hate for acts that had nothing to do with them, some national leaders are exploiting these horrendous events for their own benefit.

The actions of the presidents of Turkey and Pakistan to sow division and attack the French state have done little more than incite even more hate and anger. I’m choosing not to repeat their claims – as I don’t believe any good comes from dissecting their words – although others have.

There is not nor ever can be any excuse for murdering innocent people. This is all the more true in a democracy, such as France, where people have the legal right to protest, to challenge their politicians in court, to campaign against them and to write daily in national newspapers. We have legal ways to challenge the status-quo – violence is never a legitimate tool of protest and there can be no excuses made for its use.

Index’s raison d’etre is to defend our collective rights to free speech and free expression. That doesn’t mean that we don’t appreciate the tensions that exist between all of our basic human rights as outlined by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

There can be a tension for some between the right to free speech and the right of freedom of thought, conscience and religion. These tensions should be considered and discussed in every home, school and institution in every country. There should be a national conversation about how we find a balance as a society, we should use more words and have more debate about the type of world we want to leave in. And we should do all of this without the threat of violence.

We stand with the people of France, as they mourn the loss of Samuel Paty, Vincent Loques, Simone Barreto Silva and Nadine Devillers – may they rest in peace.

And we stand for the values that they represented.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Nov 20 | China, Hong Kong, News and features

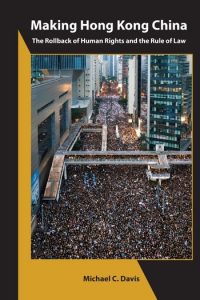

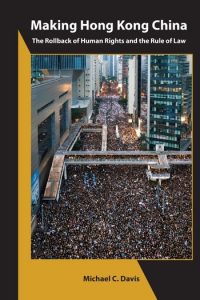

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] In 2019, the world looked on as millions of ordinary Hongkongers took to the streets to protest a proposed extradition law and to demand democratic reform. People around the globe were witnessing a piece of this great city’s history and feeling every ripe emotion alongside Hong Kong’s determined protesters.

In 2019, the world looked on as millions of ordinary Hongkongers took to the streets to protest a proposed extradition law and to demand democratic reform. People around the globe were witnessing a piece of this great city’s history and feeling every ripe emotion alongside Hong Kong’s determined protesters.

That moment is where this narrative begins. It is the story of a city whose people, since the handover in 1997, have felt the full catalog of emotions inspired by the onslaught of authoritarianism—anxiety, hope, despair, trepidation, and fear. Anxiety has always been part of Hong Kong’s handover story. Hope rose both from the signing of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration and the passage of the 1990 Hong Kong Basic Law, as well as from later widely-supported popular protests for political reform. Despair was fueled by Beijing’s ignoring of such popular demands. Trepidation stemmed from the violence on the streets and a worry that Beijing might respond with heavy-handed repression. Fear is what has now settled on the community.

One year after the protests began, and twenty-three years after the handover, 2020 has given way mostly to a level of fear, unseen before in Hong Kong, about the future. At the center of it all is anxiety about the arrest of anyone who might have once dared to speak up, brought on by the new national security law. Beijing’s direct intervention has exposed its profound distrust of Hong Kong’s institutions, as it installs various direct controls at all levels of the criminal justice process, including the executive, the police, the Justice Department, and the courts. This intervention has brought a chill to Hong Kong’s much vaunted rule of law, its dynamic press, its world-class universities, and its status as Asia’s leading financial center.

This chilling effect is especially dramatic because of Hong Kong’s long-established status as the freest economy in Asia and the world. This freedom, however, is not limited to economics: there are many dramatic distinctions between life in Hong Kong and life on the mainland. These differences have breathed a very distinct identity into Hong Kong, and they have driven the passions that have exploded in the Hong Kong protests.

In fact, it is this very freedom that China sought to preserve with the “one country, two systems” model embodied in the Joint Declaration and the Basic Law, which was enacted to carry out the 1984 treaty. This is a point that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems to have long forgotten, as a lack of political will to uphold these commitments has taken over.

But to understand what is now lost for Hong Kong and the world, we must acknowledge what this city long had, and how it differed from the systemic repression in mainland China. Perhaps the most celebrated distinction is Hong Kong’s annual vigil of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen massacre in Beijing. Hong Kong was long the only place on Chinese soil where such a remembrance was permitted—at least until 2020, when it was disallowed due to the coronavirus pandemic. I have attended most memorials since that violent day in 1989. And now, I fear that a similar fate by another means awaits those who continue to ardently defend their city’s dying democracy. For Hong Kong, this fate may arrive by a slow burn instead of tanks in the street, but the destination may be the same.

…..

For the first time in my thirty years of teaching human rights and constitutionalism at two of Hong Kong’s top universities, the contents of my syllabus might be cause for arrest or dismissal. Every year I have lamented that my course was illegal just thirty miles away on the mainland, joking wryly with my students that one of the starkest differences between Hong Kong and the mainland is found in our classroom. The entire syllabus is prohibited on the mainland by China’s famous Document 9, which forbids promoting topics like constitutionalism, the separation of powers, and Western notions of human rights.

Many in the academy now wonder whether this national security law brings something akin to Document 9 to Hong Kong. A rash of dismissals of Hong Kong secondary teachers for supporting the 2019 protests had already raised concern that only a syllabus friendly to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) can now be taught, or that teachers who differ with such directives will soon be exposed. Will such pressures threaten the global preeminence of Hong Kong’s universities, with several now ranked among the top fifty in the world? Will professors who speak up, or who freely teach sensitive topics, and encourage or inspire dedication to the same, risk arrest or dismissal under the new law? …

Looking beyond academics, Hong Kong’s legal profession has special cause for concern with the changed conditions under the new law. Several changes strike at the very heart of Hong Kong’s rule of law. Hong Kong has long had a very active and progressive bar, which has recently expressed deep concern about the new national security law. The Hong Kong Law Society, the membership organization of solicitors under Hong Kong’s divided profession, has also had many active human rights defenders.

Both law associations are right to be concerned. On July 7, 2015, in the so-called 709 Incident, Chinese authorities on the mainland rounded up around 250 lawyers, advocates, and other human rights defenders. The bulk of them were charged under China’s national security laws, either with “subversion of state power” or “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” and possibly incitement of the same. These lawyers, who were generally found guilty, were mostly organizing and providing legal defense to human rights activists and protesters. … Will the mainland system regarding the treatment of human rights defenders now come to Hong Kong under the heading of national security?

Groups of Hong Kong lawyers have been providing pro bono or low-cost defense of the many protesters who were arrested in 2019. A progressive lawyers’ group has also politically advocated against human rights violations in relation to the protests. What risks do these lawyers face?

The new national security law raises a host of concerns for national security trials. Under the new law, only a select panel of judges are allowed to try national security cases locally, and those judges can be dismissed from the select list of national security judges if they make statements that are thought to endanger national security. …

The gaping differences with the mainland, easily discernable to the casual observer, of course, go well beyond street protests and academics or the law and lawyers. These differences touch ordinary people’s lives in many ways. Before the new national security law was passed, a bookstore or bookfair in Hong Kong could have a full selection of books commenting on local or global affairs or even criticizing China’s leaders. Such books, including an earlier one of my own, were all banned on the mainland, though the tendency of mainland companies to own most local bookstores in Hong Kong already imposed self-censorship.

Nevertheless, pretty much any book or reading source could be obtained either in stores or online. The availability of a wider selection of books was long an attraction for mainland tourists who would then have to figure out how to smuggle them home. Within a week of the passage of the new national security law, public libraries in Hong Kong were already removing sensitive books from the shelves, and schools were being told to ban certain forms of protest speech.

…

These freedoms and much more are now at stake under the national security law. This new fear was clearly understood, when just hours before the new national security law went into effect, several organizations, including an activist group called Studentlocalism and the prominent local political party, Demosisto, disbanded. Demosisto had planned to run candidates for the Legislative Council in the coming September 2020 election. The party’s alleged sin was its earlier—and later dropped—promotion of self-determination for Hong Kong. Compared to those few who advocated for independence, this is a moderate position. Four former members of Studentlocalism would later be arrested, allegedly for organizing a new pro-independence group and calling for a “republic of Hong Kong.”

Though it was not introduced as such, the new national security law is effectively an amendment to the Hong Kong Basic Law. Like the Basic Law, it expressly provides for its own superiority over all Hong Kong’s local laws. It is also seemingly superior, where any conflicts exist, to the Hong Kong Basic Law. The Basic Law and the national security law are both national laws of the PRC. Under principles contained in the PRC Legislative Law, a national law that is enacted later in time and that is more specific in content is superior to an earlier, more general national law. Independent of such legal niceties, a local Hong Kong court would be in no position to declare any part of the new national security law invalid for being inconsistent with the human rights guarantees in the Basic Law.

Earlier, when a Hong Kong court had the temerity to declare invalid a government ban on the wearing of face masks, which protesters were wearing during the 2019 demonstrations to hide their identity, officials in Beijing immediately slammed the court. They declared that there was no separation of powers in Hong Kong and thus no basis for the judicial review of legislation—a claim long disputed by local judges. Intimidation was clearly intended and the court of appeals backed off, reversing the trial court and upholding most of the ban. In an ironic twist, with the pandemic in 2020, masks are required to be worn in public areas.

Such constitutional judicial review, long a bedrock of the Hong Kong legal system, has frequently come under mainland official threat. In the national security law, Beijing has again demonstrated its distrust of the Hong Kong courts by expressly assigning the power to interpret the new law to the standing committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), and by blocking judicial review of national security officials.

With this new national security law incorporated into the Basic Law fabric, Hong Kong effectively has a new hardline national security constitution. No heed was taken of the deep concerns about the city’s evolving character expressed eloquently by millions of Hongkongers marching through Hong Kong’s sweat-drenched streets in the summer of 2019.

Michael C. Davis is visiting professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of Hong Kong, where he teaches core courses on international human rights. His book Making Hong Kong China: The Rollback of Human Rights and the Rule of Law is published this November by Columbia University Press.

It assesses the current state of the “one country, two systems” model that applies in Hong Kong, juxtaposing the people’s inspiring cries for freedom and the rule of law against the PRC’s increasing efforts at control. Chapters look at the constitutional journey of modern Hong Kong, discussing the Basic Law; Beijing’s interventions and the recent historical road to the current crisis; Beijing’s increased interference leading up to the 2019 protests; the 2019 protests and growing threats to the rule of law; the national security law launched in mid-2020; international interaction and support; and finally, the current status of Basic Law guarantees as they may shape the road ahead. Click here for more on the book.

…[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Nov 20 | Artistic Freedom Commentary and Reports, News and features, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115539″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship’s What the Fuck!? podcast invites politicians, activists and celebrities to talk about the worst things going on in the world, why you should care and why you should swear.

In each episode, a guest – a free speech activist, a journalist, a celebrity or someone in the news – will tell listeners what is making them angry in the world and the words they say when they do.

Guests on the What the Fuck!? podcast will come from across the full range of opinion on the key issues shaping the modern world.

Each guest will be invited to talk about the work they are currently doing or admire relating to artistic, academic or media freedom.

The podcast ends with our guests telling us their favourite sweary expression and why it makes them feel the way it does.

In this launch episode, Index’s associate editor Mark Frary talks to photographer and artist Alison Jackson, who is renowned for her explorations into how photography and the cult of the celebrity have transformed our relationship to what is ‘real’.

She talks about her latest work, a sculpture of President Donald Trump in a compromising position with Miss Universe, the US elections and why the President needs the oxygen of publicity. She discusses the very real challenges of artistic censorship and how she challenged this by driving her Trump sculpture around the streets of New York, bringing the streets of Manhattan to a standstill.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

09 Nov 20 | Africa, News and features, Nigeria

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Recent protest in Nigeria. Credit: TobiJamesCandids/WikiCommons

A few weeks ago, Nigeria looked to be at breaking point. President Muhammadu Buhari had called in the army to quash large-scale protests that had filled the country’s streets.

Rather than allow peaceful protests, the army were responsible for a number of state killings as they fired upon their compatriots. For example, on 20th October, in the city of Lekki, around 12 people were killed, according to human rights group Amnesty International. This and other examples of violence shown on social media provoked real anger.

While the protests have died down, the desire for change has not gone away. With their right to free speech violently infringed upon by their own army, Nigerians are looking for alternative ways of protesting.

Poet and journalist Wana Udobang shed light on how the movement has adapted and on the feeling in the country.

“I think that hope was so high that by the time the 20th happened, and the army opened fire, we all encouraged people to stay home,” she said. “We all wanted change but nobody wanted people to die.”

“We have moved into the stage of [looking at] what we do strategically. If you go on social media, a lot of the talk is about getting young people into leadership and where they can make and impact change. There is an active movement for a more sustainable change. In a way, the protests were a first step in demanding for accountability and change. For a long time we were just voting between the devil and the deep blue sea.”

The protests originally began against the Nigerian police unit known as the “special anti-robbery squad”, or “SARS”, but have since become more of a protest aimed against police brutality and wider law enforcement. SARS was actually disbanded on 11 October, but demonstrations continued thereafter.

Udobang said: “It [the protests] was necessitated by the end SARS protests but I think that became like an umbrella for so many unjust things happening in the country.”

“I think [we are in] a kind of limbo period,” she said. “The protests were so hopeful. Everyone was going out every single day, people were donating food and money. It really was something where everyone felt like for the first time they could channel their energy towards something and we were all united for the first time in a very long time.”

Founded in 1992, the extra power given to SARS led to repeated incidents of police brutality and a unit that exercised fear over the civilians they were supposedly meant to protect.

Media freedom has been a notable victim of SARS brutality, with reporters repeatedly attacked and threatened by the unit. However, for a shift to take place, journalists must be protected. This, as well as being able to voice criticism towards the authorities, will be key to any kind of movement that brings about change.

“I think the role of journalists is incredibly important now,” noted Udobang. “This protest was happening during a global pandemic. A lot of the images shared were coming from Nigerians themselves. So the importance of documenting change, movements and what was essentially a massacre. The government did not acknowledge it.”

The country sits 115th in the World Press Freedom Index. Press freedom protection organisation Reporters Without Borders describe why Nigeria is so low down the rankings.

“Nigeria is now one of West Africa’s most dangerous and difficult countries for journalists, who are often spied on, attacked, arbitrarily arrested or even killed,” they said.

“The defence of quality journalism and the protection of journalists are very far from being government priorities. With more than 100 independent newspapers, Africa’s most populous nation enjoys real media pluralism but covering stories involving politics, terrorism or financial embezzlement by the powerful is very problematic.”

“Journalists are often denied access to information by government officials, police and sometimes the public itself.”

While the true impact the protests have had on Nigeria and its institutions is currently unclear, the demonstrations seem like a turning point for people in the country. Let’s hope it leads to more freedoms.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”5641″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

09 Nov 20 | Index in the Press

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Ruth Smeeth, Index’s CEO, explained her criticism of the proposed removal of the “dwelling” privacy exemption currently in UK law.

The change would mean a legal grey area where people could theoretically be prosecuted for something they say in their own homes.

“We need to have a proper national debate if we are going to start putting restrictions on language like this. There could be unintended consequences. People have a right to debate issues at home. If someone reads from Mein Kampf at home because they are studying it, would they get reported to the police? Where do you draw the line between intellectual curiosity and crime?”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

09 Nov 20 | Index in the Press

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index CEO Ruth Smeeth warned of new legislation in Scotland that would “govern what we say to each other over a cuppa”.

The new “hate crime bill” proposed in Scotland has been heavily criticised since its inception.

In The Times, Smeeth said: “Common sense seems to have gone out of the window with regards to the Scottish hate crime bill. Let’s be clear, hate speech is appalling and if it’s inciting violence and illegal behaviour it should be banned. But this is now trying to regulate what people say to each other over dinner — it’s absurd. We need a legal framework to protect the general public from the impact of hate crimes, not a piece of legislation to try and govern what we say over a cuppa.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

06 Nov 20 | Opinion, Ruth's blog, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115489″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]As I type we are still awaiting the final vote tallies for the US elections and while it looks like we will have a new president inaugurated in January, we’re still awaiting confirmation.

I am a politics addict. I love elections. I love campaigning. But most of all I love the fact that elections are a demonstration of public will. In a democracy, every person’s voice is heard and carries the same weight – at least that’s the plan. It is, and should be, one of the purest forms of an individual’s freedom of expression. This is an opportunity for our voices to be heard, to endorse or to challenge the status quo. It is our time to send a message about what type of society we want to live in and who embodies that desire. This is the fabric of our democracy and is at the heart of who we are.

Elections also send a message to the world about the resilience of a nation state’s democratic processes. Which is why events in the USA this week have been such a concern. In the middle of a global pandemic it should be no surprise to anyone that the results were going to take a while. Given the fractious nature of US politics over the last four years we also shouldn’t be surprised at the political rhetoric, centred on the concept of election stealing, emerging from the White House. But the cynical undermining of the core premise of free and fair elections is so dangerous and not just because of the impact that it will have on US society.

US elections set a bar for emergent democracies around the world. They give the USA the moral authority to challenge authoritarian and repressive regimes. They also, vitally, inspire hope in people around the world who seek to have their own voices heard.

Which is why it is so concerning to not only be watching events unfold but to have read the OSCE’s independent assessment of the election. While praising the organisational competence of the election officials they stated that: “Nobody – no politician, no elected official – should limit the people’s right to vote. Coming after such a highly dynamic campaign, making sure that every vote is counted is a fundamental obligation for all branches of government. Baseless allegations of systematic deficiencies, notably by the incumbent president, including on election night, harm public trust in democratic institutions.”

These comments alone give succour to dictators around the world. What criticism can the US state department level at national leaders who seek to undermine their own democratic processes if the US president has questioned the validity of his own democracy?

The imminent result is therefore not just incredibly important for Americans, but vital for the rest of the world. Which is why I keep refreshing the vote count in Philadelphia County…[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

03 Nov 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A Women’s March in 2017. Credit: Mark Dixon/Flickr

“I had a second trimester abortion,” tweeted Erica Goldblatt Hyatt, a Canadian living in the USA. “Our son never formed an airway. Had he survived birth he would have been brain dead. That wasn’t the life I wanted for him. It was the first true parenting decision I ever made.”

Goldblatt Hyatt’s story was included in a CNN article, along with stories from a mother of two who didn’t want more children and a woman who got pregnant at 16 with no family support, about the reasons women have abortions.

Since the passing of Roe v Wade in the Supreme Court in 1973, abortion has been enshrined in law in the USA. Some states have restrictions on access to abortion, but the ruling that it is a legal right has remained in place.

The passing of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in September, and her replacement by Amy Coney Barrett, has fuelled the fire of panic in women that this right could soon be snatched away, a panic they have felt since 2016 when Donald Trump said that if he is able to select enough justices for the bench, over-turning Roe v Wade “will happen automatically”.

The USA is not the only country where reproductive rights are being dismantled. Mass protests have broken out in Poland over the last few weeks after the constitutional court ruled that, even in the case of severe foetal abnormalities, women will be forced by law to carry the pregnancy to term. This is a further encroachment on reproductive freedom in a country that already has some of the most restrictive abortion laws in Europe.

The women of Northern Ireland are also facing barriers to reproductive freedom. Despite abortion being decriminalised in October 2019, access to clinics is severely lacking, prompting the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists to write a letter, sections of which were published by the Independent on 26 October, warning of the risks to women.

“There have already been at least two cases of attempted suicide by women in Northern Ireland unable to access care,” it says, adding that there has been a dramatic increase in women “turning to unregulated methods of abortion during the pandemic.”

Reproductive rights are a freedom of expression issue. We do not only express ourselves verbally and artistically, we express ourselves through the choices we make about how we live our lives and what happens to our bodies. The decisions about when, if ever, to become a mother, and to how many children, are some of the biggest a woman can make. When states take control of this decision, they are taking control of our self-expression.

This is not to say that these decisions cannot be discussed and debated. Debate is at the heart of freedom of expression and that extends to the topic of abortion. People should be allowed to talk about the questions surrounding it, such as “when does life start?” For some it starts at the moment of conception, meaning abortion at any stage, even the very early weeks, would constitute ending a life. But this is not a consensus. And even if life does start at conception, that would not necessarily mean that abortion should be banned. After all, there are all kinds of practises that we allow as a society even if we question them morally because we believe banning them would ultimately go against freedom and autonomy.

Pro-life advocates must of course have their right to this view respected, and no one should force them to abort. But equally people attempting to force their beliefs on others, and control their actions to be in line with these beliefs, is when the defenders of freedom of expression must step in.

It should go without saying that the consequences of being forced to have a child are far-reaching. There’s the toll on mental health for one. According to research by scientists at King’s College London one in four pregnant women suffer from mental health problems. This can be even more extreme for those in unwanted pregnancies. In 2017 a young woman, who became known as Ms Y, sued the official health service in Ireland after she was not only denied an abortion but held against her will and forced medication to prolong the pregnancy. She had arrived in Ireland in 2014 seeking asylum and soon discovered she was pregnant. She said she’d been raped and was suicidal because of the pregnancy.

Research also shows that having a baby can hold a woman’s career back six years. Inflicting career disruptions on women by forcing them to continue with unwanted pregnancies is an infringement on their self-expression in the workplace that can have long-spanning repercussions. And then there are all the negative impacts it can have on relationships, finances, social support networks – the list could go on. None of these are trivial matters. Rather they’re all choices that are part of our free expression.

The Polish ruling also highlights that many abortions are because either the baby or the mother, or both, are seriously ill. Abortion is not always a lifestyle choice. It is often a very traumatic decision a woman is forced to make about an intended pregnancy. Heart-breaking as these decisions undoubtedly are, the most profound forms of expression are often the choices we make about our health and that of our families.

Incidentally, as is often the case with censoring behaviour, removing someone’s choice can actually be counter-productive. A study by the National Library of Medicine concluded that women who had had an abortion were more likely to have an intended pregnancy within the next five years than women forced to continue with an unwanted pregnancy. Diane Greene Foster, one of the academics who conducted the study, concluded: “Being able to access abortion gives women the opportunity to have a child later with the right partner, at the right time”. She added that a woman who is denied an abortion is likely to “face diminished opportunities to achieve other life goals, gain secure financial footing, and have a child she can cherish and support”.

Remaining childless, or having children with the right partner when it is the right time to do so, is an umbrella of self-expression under which so many other forms of expression shelter; expression through work, through lifestyle choices, through parenting ability. It is a form of expression which must remain in the hands of individuals and be kept out of the grips of the state.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

02 Nov 20 | Belarus, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115442″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Harassment, round-ups, arrests and imprisonment have become routine for journalists working in Belarus in the nearly three months since the presidential elections on 9 August. Add to that a lack of internet access and it becomes clear that those covering the protests in the country since Alexander Lukashenko won a widely contested fifth term as president have been working in incredibly difficult conditions.

According to data from the Belarusian Association of Journalists, from 9 August to 1 November, Belarusian and foreign journalists were arrested more than 310 times just for doing their job. Of these, in more than 150 cases they spent three or more hours in police stations. In 60 cases, journalists reported that they were subject to violence in the process of their work, during and after detention, including some cases of torture.

Despite the fact that under Belarusian law journalists have a number of rights, they are not being protected from abuse, but are subject to purposeful actions by the police and special forces. When arrested, most journalists were wearing press vests,had badges and press cards.

There are no investigations into the arbitrary detention of journalists. There is not a single criminal case initiated over journalists` complaints about the violent actions of the police. Examinations of the facts in these cases by he Investigative Committee – the unified system of state law enforcement agencies are being unduly prolonged again and again without any sufficient grounds.

Thus, impunity for harassment of journalists has become normal for post-election Belarus. What is more, their professional activities relating to the coverage of protest rallies have become grounds for judicial prosecution. From the day of election to 1 November, about 60 journalists covering election-related protests were charged with alleged participation in an unsanctioned demonstration under Article 23.34 of the Code of Administrative Offences. Approximately a half of them were sentenced to jail terms from three to fifteen days and the others were fined.

Foreign journalists have also been subject to special sanctions. At least 50 foreign journalists were banned from entering Belarus after the election. According to an official statement from the State Border Committee on 18 August, , 17 foreign media workers were denied entry in Belarus “due to the lack of accreditation to carry out journalistic activities in the territory of our country.” Journalists from at least 19 foreign media outlets have been deprived of their accreditations. All who were foreign nationals have been deported from Belarus. On 2 October, the Foreign Ministry revoked all the previously issued accreditations for foreign journalists due to the adoption of a new regulation for accreditation. Thus, all of them were outlawed until they had obtained new accreditation.

On 1 November, a protest march took place from Minsk to Kurapaty, where victims of Stalin’s repressions were executed and buried. On this one day, seven journalists working there were arrested, two of them were beaten up, and four were left in jail pending trial.

Media outlets are being targeted too with access to independent sources of information deliberately restricted by the government. In late August, the Ministry of Information ruled to block more than 70 news websites and websites of civil society organisations. After the election, state-owned printing houses refused to print some influential independent newspapers – Narodnaya Volya, Komsomolskaya Pravda in Belarus, Svobodnye Novosti Plus, and Belgazeta – on flimsy or no grounds at all. . When two of the newspapers printed their issues abroad, the state post service Belposhta and monopolist newsstand chain Belsayuzdruk made it impossible for them to distribute them.

Despite this, the media continue to do their job: blocked websites disseminate information through “mirrors”, Telegram channels and social networks; print newspapers are distributed by volunteers; journalists support each other.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”172″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Oct 20 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Donald Trump taking questions at a press conference on Covid-19. Credit: WikiCommons

By this time next week, we will hopefully (subject to the courts, likely delays and the impact of Covid) know who the future leader of the USA will be. In an election that feels like it has been raging from the moment that Donald J Trump was inaugurated as the 45th president of the United States, it will be a relief when it is finally over.

But we need to look beyond the campaign hype and explore the longer term impact of the relationship between the White House and the media, which has become a little fraught to say the least.

According to the US Press Freedom Tracker, Trump has undermined and attacked the media a total of 2434 times since he was confirmed as the Republican candidate in 2016. Indeed within just days of taking office, he took the opportunity to label journalists “the enemy of the American People” in words that many saw as echoing those of Stalin and the Nazis, as the great granddaughter of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev wrote in Index on Censorship magazine at the time.

For a country built on the premise of a free press and with free speech enshrined in law it’s an appalling indictment of the current state of acceptable political discourse in the USA.

The First Amendment is one of the most revered and easily understood of all the additions to the US Constitution. At its heart is the idea that each and every US citizen has an inalienable right to their own freedom of speech and assembly. But it also confers the absolute protection for the press to report freely and as they see fit. It reads:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Of course when the Founding Fathers drafted this no one could have envisaged the role of social media and how, a president with a gripe, could use it to undermine the press and deliberately seek to use his power to target journalists who report on his activities in a way he does not agree with.

Ahead of the final presidential debate, Trump took to Twitter to denounce the moderator and renowned journalist Kristen Welker as “terrible & unfair, just like most of the Fake News reporters”.

Trump said to Jeff Mason, the highly respected Reuters journalist, on a visit to Arizona, “Let me tell you something: Joe Biden is a criminal, and he’s been a criminal for a long time. … And you’re a criminal, and the media, for not reporting it.”

Trump has declared that on 3 November “We’re not just running against Joe Biden. We’re running against the left-wing media…”

Trump is, of course, entitled to use his freedom of speech to criticise the press. But he has taken this a step beyond normal criticism of the media. From early in to his administration news organisations whose editorial line might not be favourable towards Trump have been barred from press briefings. And these interferences in normal due process have only accelerated, especially during the current pandemic, as our Covid media tracker highlights.

A malevolence has seeped into presidential communications that seeks to undermine and delegitimise reporters who produce editorial content that does not fit the White House narrative. And as we head to the election, it seems that the Trump administration increasingly wants to take aim at the First Amendment and double down on their attacks on the free press.

This month, in an unprecedented move, the head of the US Agency for Global Media (a Trump appointment) has scrapped the ‘firewall’ that protected the editorial freedoms of Voice of America and other broadcasting agencies that receive public funding. The repeal memo claimed that the firewall was in conflict with the agency’s purpose to promote the interests of American overseas. Michael Pack, the CEO of the IS Agency, claimed that the agency “do not function as a traditional news or media agency and were never intended to do so.” He added: “For example, the Networks are to articulate the American perspective while countering international views that undermine American values and freedom, or that might aid our enemies’ messaging.”

The Agency for Global Media runs Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and Radio Free Asia. Both are intended to provide independent news to audiences in countries where media freedoms are curtailed and yet now they may be used to produce nothing more than partisan propaganda for whoever wins the White House next week.

And as Index reported earlier this week, plans to change the I visa terms for foreign journalists operating in the USA have been suggested. If passed, these plans would represent a serious setback to media freedom.

None of this is even vaguely in keeping with the spirit of the First Amendment. It does little to support and promote the USA’s place in the world. Instead it undermines global free speech and as such shouldn’t be ignored by the wider global family.

On Tuesday we will hopefully find out what the USA’s long term priorities are. Be assured that we will be shining a light on whoever wins if they fail to protect our global freedom of speech and if they fail to promote and protect the media.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Oct 20 | Iran, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115414″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]“We are caught up in a shadow play, only part of which we get to see.”

These are the words of Richard Ratcliffe, the husband of British-Iranian charity worker Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who has been in solitary confinement and prison in Iran since 2016 for plotting against the Iranian government, charges she denies and which most people believe are fabricated.

His comments came as it was revealed that Nazanin will have to return to court next Monday, 2 November, to face yet more charges. She was temporarily released under house arrest in March because of the Covid pandemic but the authorities have told her to pack a bag, effectively suggesting that the case against her has already been decided and that she will return to jail.

Speaking to Index after the new court date was announced, Richard said, “These are days of trepidation in the build-up to Nazanin’s court case. It’s clear that bad things will happen, but also that we are caught up in a shadow play, only part of which we get to see. Just how bad is hard to know. Is this just to extend Nazanin’s sentence? Is it to take her back to a solitary cell? It is hard to keep imaginations calm. It feels like we might be back to the beginning.”

The beginning was 3 April 2016 when Nazanin was arrested by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard as she was leaving the country with her then two-year-old daughter Gabriella.

At the time, Nazanin was working as a project manager for the Thomson-Reuters Foundation which delivers charitable projects around the world and does not work in Iran.

Initially, Nazanin was transferred to an unknown location in Kerman Province, 1,000 kilometres south of Tehran, where she was held in solitary confinement.

In September 2016, she faced a secret trial where it was claimed that she had been helping to provide training for journalists and human rights activists in a plot to undermine Iran’s government. Nazanin was sentenced to five years in prison on unspecified charges relating to national security.

After eight and a half months in solitary confinement, Nazanin was transferred to the women’s wing of the infamous Evin prison in Tehran, home to many political prisoners.

The next year, then foreign secretary, Boris Johnson issued a statement saying, “When we look at what Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was doing, she was simply teaching people journalism, as I understand it, at the very limit.”

His remarks were widely criticised and Nazanin’s employer issued a rebuttal, saying that she was never involved in training journalists in the country. Four days after Johnson made his remarks, they were used in a further court case against Nazanin when she was told that she could face an additional 16 years in prison.

Also in Evin prison is Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, a writer and political activist who is serving a six-year sentence for charges related to an unpublished story she wrote criticising the practice of stoning in Iran.

Following Index’s tradition of publishing the work of imprisoned writers – dating back to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – we published poetry by Nazanin and Golrokh in a bid to support their cases. You can read the poems here.

Writing about her daughter Gabriella, then three, Nazanin wrote: “The diagonal light falling on my bed / Tells me that there is another autumn on the way / Without you.”

In March 2019, the UK government granted Nazanin diplomatic protection saying her lack of access to medical treatment and lack of due process in the proceedings brought against her were “unacceptable”.

The move failed to secure her release as has a petition which almost 3.5 million people from around the world.

Some, including husband Richard, believe that Nazanin is being held to put pressure on the UK government over a cancelled £650 million deal for military vehicles agreed with the Shah of Iran before he was deposed in the 1970s. Iran says that the UK owes it substantial interest on the unpaid debt.

Richard says, “We are clearly caught in a game of cat and mouse between Iran and the UK, and we have been pushing for a long time for the UK government to take responsibility for protecting Nazanin and the others, to stand up for their rights.

One of the staunchest supporters of the campaign to free Nazanin is her MP in the UK, Labour’s Tulip Siddiq.

Siddiq told Index: “Nazanin has once again been treated with utter contempt, and I am extremely concerned about her future and wellbeing. The fact that she has been told to pack a bag for prison ahead of her court hearing doesn’t fill me with confidence that this will be anything close to a fair trial.

“The timing of this development alongside the postponement of the court hearing about the UK’s historic debt to Iran raises serious concerns. I can only hope that there is work going on behind the scenes to resolve the debt quickly because we seem to be going in completely the wrong direction and Nazanin, as ever, is paying the price.”

She added, “The foreign secretary must assert the UK’s right to consular access and ensure that UK officials are present at Nazanin’s trial.”

Responding to the news of the new court date, Dominic Raab said, “Iran’s continued treatment of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe in this manner is unacceptable and unjustified. It tarnishes Iran’s reputation and is causing enormous distress to Nazanin and her family. Iran must end her arbitrary detention and that of all dual British nationals.”

Does the foreign secretary’s comment give Richard confidence that the UK government will bring effective pressure to bear on Iran?

“Rather less than four and a half years ago. But tomorrow is always another day.”

Ahead of Nazanin’s court date, Tulip Siddiq agreed to read one of Nazanin’s poems. You can watch it here:[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/dDn34PHqUOg”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

In 2019, the world looked on as millions of ordinary Hongkongers took to the streets to protest a proposed extradition law and to demand democratic reform. People around the globe were witnessing a piece of this great city’s history and feeling every ripe emotion alongside Hong Kong’s determined protesters.

In 2019, the world looked on as millions of ordinary Hongkongers took to the streets to protest a proposed extradition law and to demand democratic reform. People around the globe were witnessing a piece of this great city’s history and feeling every ripe emotion alongside Hong Kong’s determined protesters.