07 Oct 20 | Index in the Press

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship CEO Ruth Smeeth has voiced her concerns regarding the proposed Online Harms Bill. Smeeth wrote in The Independent that the legislation, though well intentioned, would risk campaigning for ‘cultural change’ and thus have a further impact on freedom of expression online.

“If that’s the case, then as a former politician I worry about the concept of legislating for cultural change,” Smeeth said, herself a victim of online abuse. “There is absolutely a problem online and it is causing real harm, but banning language rather than engaging in education programmes screams as a political fix rather than an actual solution.”

Read the full article here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

07 Oct 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Kyrgyzstan has been plunged into chaos this week after parliamentary election results on Monday led to wide-scale protests throughout the country, which have seen the prime minister resign as a result.

Protests began as soon as the results were announced and quickly became violent, with protesters storming the parliament building and setting parts of it on fire. “By 9 o’clock there were the sounds of explosions and grenades,” said journalist and writer Caroline Eden in our interview with her, who has been watching the protests unfold from the capital city Bishkek.

One group managed to break into prison and release former president President Atambayev from jail, where he was serving a sentence for corruption. Hundreds have been injured in the protests and one person has died.

Many in the country felt the elections were irrelevant even before they took place, and some had called for them to be postponed due to the Covid pandemic. Despite this, the elections went ahead but arguments between the current and former leaders of the governing Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan meant that the party did not take part, with many smaller splinter groups taking its place.

In the event, just four parties on the ballot managed to get a big enough share of the vote to win some of the 120 seats in parliament that were up for grabs. The party that won the smallest number of seats – just 13 – was the only one of the four that were in opposition to the incumbents.

The Central Electoral Commission annulled the result a day later.

Listen to Eden’s interview in full about the atmosphere on the ground and what it all means for freedoms in the country.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

06 Oct 20 | Volume 49.03 Autumn 2020, Volume 49.03 Autumn 2020 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The award-winning writer speaks to Rachael Jolley about the inspiration for her new short story, written exclusively for Index, which looks at the idea of ageing, and disappearing memories, and how it plays out during lockdown.”][vc_column_text]

British-Canadian writer Lisa Appignanesi has found lockdown a difficult time to write, but despite this she has created a new short story exclusively for Index.

British-Canadian writer Lisa Appignanesi has found lockdown a difficult time to write, but despite this she has created a new short story exclusively for Index.

Appignanesi, a screenwriter, academic and novelist, said: “It’s very hard to move within the instability of the time to something imaginative.”

Her story, Lockdown, focuses on an older man, Arthur, who reflects on his past in Vienna during the period between the two world wars.

Appignanesi has a long relationship with the Austrian city.

“I’ve done an awful lot of work on Viennese literature and, indeed, on Freud, so Vienna always feels very, very close to me and I lived there for a year,” she said.

“Vienna is a fascinating place. It was a great city – first of all head of an empire with many, many immigrant groupings in it, and then when it lost its imperial status in World War I it was a very impoverished city.”

She says the period of lockdown focused her mind on the restrictions imposed upon the elderly. “I have long thought about what happens to the mind within the body, people’s relationship to time in that sense. You grow old and stuff happens to your body and, initially at least, it doesn’t seem to affect your mental capacity and the way you grow through time as you are living it.”

She is also interested in the idea of people being present in different ways and how, for instance, the potential anonymity and the disembodied nature of Twitter means that people can unleash their anger differently from how they would if they were in the room with someone.

“Some of the rampant emotions of our time, particularly anger,” she said, “were to do with the fact that people on Twitter are not only anonymous but they are disembodied.”

In an article for this magazine in 2010, Appignanesi wrote: “The speed of communication the internet permits, its blindness to geography, seems to have stoked the fires of prohibition. The freer and easier it is for ideas to spread, the more punitive the powers that wish to silence or censor become.”

Appignanesi, a long-time campaigner for freedom of expression, was born in post-war Poland as Elżbieta Borensztejn. Her Jewish parents had what she has described with understatement as “a difficult war”, hiding under different aliases to escape arrest. The family moved then to Paris, which she remembers, and later to Montreal, Canada. She once told BBC Radio 3 that she “grew up with the ghosts of those that died in the concentration camps”. Given the family history, it is no wonder she worries about authoritarian governments and restrictions on speech.

She is now concerned about how governments are changing the rules of freedom of expression while the world is distracted by Covid-19, and the threats that may manifest themselves. “Your attention is distracted by something – something happens behind the scenes, and usually the same people are doing the distraction. This time it was the virus.”

One news item that grabbed her attention recently was about the closure of Guatemala’s police archives (see page 27), a library of information about the country’s civil war. Her concern is that “those archives are about the disappearances of people under the dictatorships, which were lethal”.

As others track governments who want to control the national story, Appignanesi says we must learn from history.

“It’s very important for our documents in Britain to be interpreted in different ways, and supplemented by stories we don’t know.

“There are always new histories to discover.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd0d0d”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The freer and easier it is for ideas to spread, the more punitive the powers that wish to silence or censor become.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Lockdown by Lisa Appignanesi:

Arthur was old. Very old. So old that when the word “lockdown” had made its way onto the radio news he was listening to with only half an ear – and even that half tuned to inner voices – he had thought they were talking about him.

It seemed the world was joining him now. In lockdown.

But the whole country had been in metaphorical lockdown for some time, he reflected, its politicians preventing every connection between a fragmented people except angry sparks or empty boasts.

Lockdown was a perfect word to describe his present condition: confined to his cell for his own good by a greater authority. If he promised not to riot, he was allowed out for exercise at regular intervals.

Yet the notion of exercise took all the pleasure out of movement. He preferred to think of it as a walk, better still, a passeggiata. He always dressed carefully for the occasion – a suit, perhaps a silk waistcoat, a bow tie. The joy of a stroll was in part that people looked at, and greeted, each other – even smiled. So no stretchy joggers and sweatshirts for him of the kind his grandchildren wore. He liked form. He had always been something of a dandy, though these days, as he heaved what seemed to be boulders rather than legs along the streets, it was harder to turn a casual half smile on the world and appreciate its offerings. But then his senses, too, were in all but lockdown. His new glasses had him stumbling, the ground far closer than where he had last left it, as if he had shrunk back to childhood and well below what was once an adequate height for a man of his generation.

His first grandson had once asked him if he was named after King Arthur since he had a round table and Arthur hadn’t liked to contradict him – but the only table that had featured in his own childhood had been the one at the Professor’s house in Vienna. He played happily under that while the adults talked and occasionally the Professor would put a hand below the edge of the tablecloth and tousle his hair, then pat him as he did his dogs. He liked the Professor, who gave his name a proper ‘T’ – Artur. In fact, it was the writer who was called the professor’s “doppelgänger” who was responsible for Arthur’s name.

Doppelgänger was a word he learned early. Another, heard from beneath the table, was Zensur. He had thought that had the word hour in it, had thought maybe it meant ten o’clock, zehn Uhr. Amidst the chatter of the adult voices, he saw TEN blotting out all the hours that came before, a censoring hour.

Maybe that’s why he had this odd relationship to time now, as he reached his midnight. He was convinced that at this late age he finally understood, was indeed living, what Einstein had meant about time slowing in the presence of heavy objects. Arthur was so light now, his bones s0 hollowed out, that time didn’t slow for him. It sped.

Or maybe its racing effect was linked to the fact that there was so little of time left that what had once been full and slow was now racing towards an end. The thought of death could no longer be censored or repressed. No bonfire could destroy it. But then it hadn’t really worked for the books either. They had sprung up in other editions and elsewhere.

Arthur had been born in Berlin just weeks after the great conflagration of books the Nazis had staged and only a few months after the Reichstag fire. His mother had been walking near the Staatsoper on the night of the book burning. She had loved Arthur Schnitzler’s work and had known him a little, so he had become little Arthur.

It was as well the Professor was still alive or he might have become Siggy, since his books were in that bonfire too.

Was that why he had spent his life in books and collected so many in the process? He looked up at the study’s walls lined in first editions, one side leather bound, the other brighter in their contemporaneity.

“Arthur?”

He checked that the voice was real and forced himself into the present.

In the doorway stood the young woman he liked to think of as his companion, though his granddaughter, Mia, had called her – in insisting on the need for her – an au pair plus. Stella was certainly more than his equal, not only as tall as he once had been but with poise and a razor-sharp intelligence he sometimes thought could penetrate his thoughts without him needing to speak.

So she knew he liked the fact she was decorous and she hadn’t – at least not yet – upbraided him for it, as his granddaughter would. Stella was completing a PhD at Cambridge, and with a rueful smile admitted that she had been completing it for an unconscionable while, which most recently had included divorcing her husband. That was why she found herself in need of a room and an extra wage. No one had imagined lockdown.

Now she wanted him up and ready to begin the Sisyphean task of the morning passeggiata.

His study door opened onto a terrace and from there down into communal gardens, a square where the trees today were in full glorious flower. He was a lucky man. Doubly lucky that his granddaughter had somehow gifted him this magnificent creature.

“We’re going to begin today,” Stella said when they paused for him to catch breath beneath the flowering cherry. The sky between its branches was a Mediterranean blue. The blackbirds were in full throat. The young Americans with their twin toddlers weren’t out yet.

“I’m not ready.” Arthur heard the plaintive high pitch in his own voice and rushed to blur it in a cough.

If you wish to read the rest of the extract, click here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Lisa Appignanesi is an award-winning writer and campaigner for free expression. She is the author of many books including Memory and Desire, Losing the Dead and The Memory Man.

Rachael Jolley is the former editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship’s autumn 2020 issue, entitled The disappeared: how people, books and ideas are taken away.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2020 magazine podcast featuring Hong Kong-based journalist Oliver Farry, who discusses the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in the region

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

05 Oct 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115172″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Books have long been objects of contention, criticised for spreading ideas which go against the status quo. They are removed from libraries and bookshops, burned, banned and vandalised while writers are attacked, threatened, imprisoned. These actions are nothing new, yet the importance of preserving our freedom to read is more important now than ever.

Freedom to read is at the centre of Banned Books Week, an initiative which has sought to challenge censorship on both sides of the Atlantic, bringing together literary communities – librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers – in shared support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.

The initiative was launched in the USA in 1982 in response to a surge in the number of challenges to books in schools. Since then, it has sought to highlight the value of free and open access to information. Each year sees an exciting strand of events, readings list, games and activities designed to get people thinking about books that have been banned throughout history, and are still causing offense today.

As the 2020 Banned Books Week comes to a close, we have a chance to reflect on the impact the initiative has had over the past 38 years, and consider the work we still need to do to ensure everyone is free to read.

Censoring literature is nothing new. It has a long and dark history and has been exercised by governments, political parties and religious groups for centuries. Book burning, which has been recorded as early as the 7th century BCE, and proliferated under the Nazi party in Germany in 1933, is emblematic of a harsh and oppressive regime which is seeking to censor or silence some aspect of prevailing culture.

Today’s methods of censorship remain prevalent yet differ in style. Political leaders use legal methods to silence or prohibit writing which paints themselves and their parties in an unpleasant light – techniques not so different to the vexatious lawsuits used to silence journalists. Academic textbooks are rewritten to paint recent historical events in a very different light, and a favourite illustrated bear has long been banned to protect the ego of other fragile leaders.

As well as these more blatant signs of government censorship, literature is still challenged today. Some of the most canonical works of the 20th century have famously been challenged – including The Handmaid’s Tale, Animal Farm and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which this year sees the 60th anniversary of its uncensored publication in the UK. But it is children’s books that cause a particular stir, such as And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell which tells the true story of two male penguins who create a family together and was subsequently banned in US schools and libraries for depicting same-sex marriage and adoption.

While this year’s Banned Books Week took a different shape from previous years, we had the pleasure of hearing a number of writers speak about their experiences of being silenced, censored or simply refused a platform. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the resultant global Black Lives Matter protests, it has been clearer than ever before that the voices of some are prioritised to the exclusion of others.

In an online session on 29 September, Urvashi Butalia spoke to poet Rachel Long, and authors Elif Shafak and Jacqueline Woodson about what ‘freedom’ means in the culture of traditional publishing, and how writers today can change the future of literature. During the event, Shafak defended freedom of speech and spoke about her experience of seeing her works of fiction brought into the courtroom – “it was very surreal to me. Art needs freedom, even though it may be harmful in the eyes of authorities.”

Shafak’s comments harked back to those made by Nobel laureate Toni Morrison during the launch of the Free Speech Leadership Council, an advocacy arm of the National Coalition Against Censorship. At the event, Morrison spoke of her novel Song of Solomon being banned at a prison after the warden expressed fear that it might stir the incarcerated to riot. An acoustical lapse led Morrison to speculate as to whether the real fear was of the inmates incitement to “riot” or “write” – asking, which would ultimately be the most dangerous?

While authorities and governments fear literary works that are seen to challenge them, we are reminded this Banned Books Week of the importance of free artistic expression and of literature’s power to challenge even the most powerful, oppressive forces. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

02 Oct 20 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”110001″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]There is no right not to be offended.

There is no right to cause harm and incite hate and violence.

These are not contradictory statements. In fact I believe that they are the founding pillars of how we should exercise our basic right to free speech in a democracy, but all too often we collectively seem to forget that.

And we ignore these basic principles at our peril; after all, none of us seek a bland public space. We thrive on debate and challenge, on new thinking and research; it drives social change, ensures progress and most importantly holds decision-makers to account.

Slavery, criminalisation of homosexuality and denying women the vote were also once legal until someone stood up and said no. These people started, at times, incredibly difficult and brave debates, launched inspiring campaigns and took people on a journey which changed hearts and minds and, of course, the law.

We can and should be able to do all of that without crossing a line into hate, without inspiring fear and without descending into violence and threat.

None of this should be controversial in a rational world; unfortunately rationality seems to be a rare commodity at the moment.

The concept of free speech has been a dominant feature in our political discourse over the last year. There has been a lot written about cancel culture, current and impending culture wars and the need to manage, if not shut down all together, debate.

Much of this has been driven by people who seek to raise their own profile at the expense of good and proper debate on serious issues that matter. This isn’t healthy for us as a society and honestly it is stifling our national conversation and leaving a political vacuum for those on the fringe to fill.

The world is facing a public health emergency and a global recession. There are serious injustices happening across the globe, both in democracies and repressive regimes. Yet we are seeing new and empowering political movements emerging demanding real equality, genuine citizenship and action on climate change across the planet.

All of these issues are going to inspire debate as we seek answers to some of the biggest questions our societies have ever faced.

Do we demand an end to globalisation because of the effects of worldwide trade on the environment?

Do we fight for public health measures as the expense of our civil liberties?

In the midst of a global recession is trade with China more important than human rights?

Honestly, in order to find the answers we need to listen to each other and not shut down the debate.

We need to hear from those being persecuted and those being marginalised. We need to listen to those people on the frontline of each issue and most importantly we need to respect each others position and opinion. In short we need to value not just our own right to free expression but other people’s too.

Index was established to be a voice for the persecuted, to provide a platform to those who couldn’t have their work published elsewhere and to shine a spotlight on areas where peoples voices were being silenced. I’m proud of that heritage and as our public space becomes increasingly hostile, I can promise you that Index will fight to ensure that we always have free and open debate[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”13527″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

02 Oct 20 | Argentina, China, Japan, News and features, South Korea

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114954″ img_size=”full” alignment=”right”][vc_column_text]“When old people speak it is not because of the sweetness of words in our mouths; it is because we see something which you do not see.”

– Chinua Achebe, Nigerian novelist

When populist governments rise, or when free speech is threatened, it so often falls to the steely wisdom of older generations to fight for justice.

Every age group has its heroes and, so often, older generations are the champions of the young.

Index has covered a range of groups since its inception in 1972 and elderly protesters have often featured. Here is a look at some of the most significant.

Belarus

Across the country, Belarusians are mass protesting current president Aleksander Lukashenko after elections in August appeared to be rigged.

At the forefront of the ongoing protests is 73-year-old Nina Bahinskaya.

The former geologist has certainly become identifiable with the demonstrations. Index’s Mark Frary spoke to her.

“I decided they [the authorities] would not be so harsh to an old lady, that’s why I decided to organise some activities myself,” said Nina.

Bahinskaya began her protesting after the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, distributing leaflets critical of the Soviet regime, so has experience demonstrating against oppressive governments.

“I don’t want it to continue because I have children, grandchildren and even a great-grandchild.”

President Lukashenko recently met with Vladimir Putin. In a showing of support, Putin agreed to give the Lukashenko government a sizeable loan. It has furthered concern in the country about the increase of Russian influence.

Bahinskaya echoed this worry, she said: “This is quite obvious that some kind of new annexation is happening.”

See Index’s most recent coverage and Bahinskaya’s interview with Mark Frary here.

Argentina

In 1976 the National Reorganization Process seized control of Argentina. The military junta were responsible for a number of atrocities. Backed by the United States as part of a ‘dirty war’, the Argentinian government committed acts of state terrorism upon its own citizens, including the forced disappearances of close to 30,000 people.

A higher value was placed upon young children and babies due to a waiting list for trafficked children. Those hopeful of adopting the trafficked children were military families and supporters of the new regime.

Lucia He spoke to one of Argentina’s ‘famous grandmothers’ for Index in 2017. Buscarita Roa, part of Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, has campaigned since 1977 for disappeared victims to be identified.

She told Index: “Even if you’ve found your own grandchild, you stay because you think of the grandmother who is sick in bed and still hasn’t found hers. To us, the grandchildren we are searching for are all ours.”

The group began protesting at the height of the fear spread by the junta. One of the two founding members of the organisation was disappeared. Its high profile led to infiltration. In 1986, an extract from the book Mothers and Shadows by Marta Traba was published in Index. It spoke of the ‘notorious’ Captain Alfredo Astiz, whose access to the group led to 13 further disappearances.

Despite its reputation, Roa insisted there was little glory in being part of the organisation.

“Being a Grandmother of Plaza de Mayo is not something to be proud of, because having a disappeared grandchild is not something to be proud of.”

Japan

In 2018, Annemarie Luck covered one of Japan’s forgotten scandals: the South Korean ‘comfort women’ or, more accurately, sex slaves.

It took until 1992 for survivors to tell their story

Luck reported that some members of the survivors’ group still meet at the same spot every Wednesday outside the Japanese embassy in Seoul.

They were first issued with a signed apology in 1994 by then Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama and in 2015, an agreement was reached between Japan and South Korea for the equivalent of $9 million.

Victims, as well as South Korean state officials, viewed the agreement as inadequate and protests have since continued.

239 women had registered with the South Korean government by 2016 as survivors of sexual slavery.

The House of Sharing in the city of Gwanju is home to many of the survivors. Team leader at the facility, Ho-Cheol Jeong, told Index of the impact the women he calls the ‘grandmothers’ have had.

Ho-Cheol said: “In a way, these women could be thought of as the original pioneers of the movement against sexual abuse and harassment that’s spreading throughout the world right now.”

Ukraine & Russia

In 2014, Index reported on the Russian government covering up its own soldiers’ deaths from the conflict in eastern Ukraine. Bereaved families were ‘discouraged’ from talking to media organisations.

Since the conflict broke out in February 2014, an estimated 5,665 soldiers have been killed

73-year-old activist and grandmother Lyudmila Bogatenkova faced a retributive accusation of fraud in response to drawing up a list of military casualties.

Bogatenkova was at the time head of a Soldiers’ Mothers branch in the city of Stavropol. The organisation provides legal advice to soldiers, as well as education programmes.

The allegation threatened Bogatenkova with up to six years in jail, before Russia’s human rights council intervened.

At the time, the BBC reported that local journalists were unable to meet the families of perished soldiers due to threats from ‘groups of aggressive men’.

China

Not all grannies are equally ready to stand up in the face of repression.

In 2013, after Chinese media frequently drew attention to stories of neglected pensioners, a new law was introduced.

The legislation stipulates that adults can face jail time or be sued if they do not visit their parents regularly.

Though brought in to Chinese law, it faced derision from across China and the globe and was not expected to be widely enforced. Many believed it was introduced to serve as an ‘educational message’.

However shortly after it was introduced a 77-year-old woman sued her daughter, who was subsequently ordered to provide financial support as well as bi-monthly visits.

The country struggles with the problem of an ageing population that, as numbers continue to reduce could cause economic growth in the region to fall.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”366″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Sep 20 | Index in the Press

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]A report by Index’s senior policy research and advocacy officer Jessica Ní Mhainín was cited in a piece in Politico about the trend of strategic lawsuits used to censor journalists. Ní Mhainín is working on a project on strategic lawsuits against public participation (Slapps), read the latest report here.

“Across Europe, powerful and wealthy people are using the law to try and intimidate and silence the journalists disclosing inconvenient truths in the public interest,” the free speech advocates Index on Censorship wrote in a recent report. “These legal threats and actions are crippling not only for the media but for our democracies.”

Read the article here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Sep 20 | Index in the Press

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Head of content for Index on Censorship Jemimah Steinfeld writes in the Independent on the trend of policing TV shows, and the debate at the BBC on biases in comedy.

“Great comedy needs free expression. It’s its lifeline. And some of the best comedy offends those on both the left and the right. That doesn’t mean it has to be completely unfiltered; comedy should not incite hatred and violence (which some are definitely guilty of). But there is a gap between this and the more subjective charge of causing offence or being biased.”

Read full article here[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Sep 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The White House, WIkiCommons

After the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, President Donald Trump was quick to fill the hole left by her on the Supreme Court.

As he nominated Amy Coney Barrett for the role over the weekend, Trump called Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg “a true American legend…a legal giant, and a pioneer for women”.

But what of Coney Barrett?

Announcing his choice for the vacant role, the president said Coney Barrett possessed “a towering intellect, sterling credentials, and unyielding loyalty to the constitution”.

As with any nominee to the Supreme Court, there has inevitably been a focus on Barrett’s stance on a multitude of issues, including particular scrutiny on key issues such as abortion and LGBT rights. However, Coney Barrett’s stance on matters of free speech has been difficult to determine.

As the Supreme Court acts as the USA’s highest court, its rulings on all matters, not just free speech, are vital. The highest court in the land has the final say and therefore, for Index, exactly where each judge stands on their own personal interpretation of the First Amendment is of paramount importance to judging the extent of the limitations to free speech.

The Institute for Free Speech – an organisation set up to “promote and defend the First Amendment” – recorded the actions of the initial candidates, for the position including the successful nominee Coney Barrett, in an attempt to gauge their overall position on free speech law. Coney Barrett does not have extensive records on dealing with cases concerning the First Amendment, but research done by IFS concludes that there are positive signs among what little cases there are.

Coney Barrett, currently judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, has been involved in a number of free speech cases since 2018. IFS reports that “Barrett may be willing to expand free speech protections in limited but nevertheless important contexts”.

But the 48-year-old’s record on dealing with whistle-blower cases has been mixed. In August this year, Coney Barrett’s court favoured the First Amendment and the right of a public employee to raise alarm. However, in the case of Kelvin Lett, a Chicago investigator who refused to change a police report under direction from his supervisor, Coney Barrett ruled: “Lett may have had a good reason to refuse to amend the report [but this] does not grant him a First Amendment cause of action.”

Coney Barrett has also faced scrutiny over her faith, with some questioning if her Catholic faith hinders her decisions. Pro-choice activists have consequently raised concerns over her views on abortion rights and whether she will curtail freedoms in that respect. That said, in an interview earlier this year, the judge stated: “I think one of the most important responsibilities of a judge is to put their personal preferences and beliefs aside. Our responsibility is to adhere to the rule of law.”

Conservative issues and tensions in the country have heightened since the Black Lives Matter protests erupted in May, after the killing of George Floyd. According to Fox News’ Harmeet Dhillon, there is clear friction “between government speech and the creation of public forums for expression” regarding the use of murals by BLM protestors.

Coney Barrett, a conservative herself, could well be ruling on this issue should it face the Supreme Court. The Washington Post has been clear to the point out that the death of Bader Ginsburg was a clear opportunity for conservatives to “cement their dominance” with a 6-3 majority on the court.

While Coney Barrett herself insists that personal beliefs should be kept aside, the majority may prompt conservatives to bring back more contentious issues to the court. The Post said: “The court’s conservative wing has outvoted liberals to carve out religious exemptions from federal laws; to strike down campaign-finance regulations as violations of the First Amendment; and to allow gerrymanders under the view there was no way to determine when a partisan legislature had gone too far.”

The jury, it seems, is still out, which is worrying for us at Index. The question of her commitment to the First Amendment and what it protects for freedoms more generally is of critical importance. Of course it comes at a crucial time, after years of a Trump administration in which freedoms, in particular of the media, have been chipped away.[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”5641″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Sep 20 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

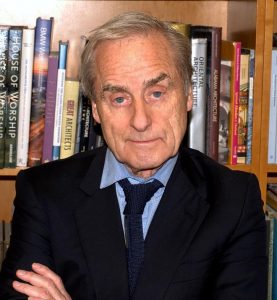

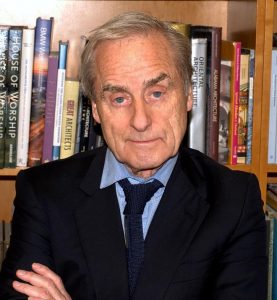

Index patron and friend Sir Harold Evans, photo; David Shankbone, CC BY 3.0

On Wednesday evening a legend passed away. Sir Harold Evans.

Harry wasn’t just a proper newspaper man, he was the staunchest of advocates for free speech both in the UK and across the world. But, most importantly, at least for us, he was part of the Index family, as a long-standing patron, friend and supporter.

Many people have written their personal stories of Harry in the last 48 hours, their experiences of a great man who embodied the best of journalism. A journalist who was fearless in challenging the establishment and shining a light on some of the most appalling scandals of his age, re-inventing investigative journalism, ensuring that his work changed minds and the law. A publisher who changed the political landscape.

Very few of us will leave such an awe-inspiring legacy.

Most importantly Harry was brave and was prepared to use his position to not only help others by exposing injustice but by ensuring that the voice of the victims was heard – most notably in his work with survivors of the thalidomide scandal.

From an Index perspective, Harry didn’t just seek to protect free speech, he relished using it. He was the first editor in British history to ignore a government D-notice, when he believed that the government were seeking not to protect national security but rather their own reputation. It’s because of him that we know the name of Kim Philby, the traitor who acted as a double agent. He stood up to the government and exposed a national scandal. In this, and on so many other issues, he published without fear or favour.

You can read Harry on the pages of Index writing about the censorship of photographs, anti-Semitism in the Middle East and forgotten free speech heroes. We were honoured to have his support and we are so saddened by his loss.

Our thoughts and prayers are with Harry’s family, friends and colleagues – may his memory be a blessing for all of them.[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”13527″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Sep 20 | News and features, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114982″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Ruth Bader Ginsburg did not set out to be an advocate for gender equality. Coming of age during the McCarthy Era of the 1950s, when freedom of speech and freedom of association were subject to intense scrutiny and repression in the United States, her initial goal was to uphold constitutional rights.

“There were brave lawyers who were standing up for those people [targeted by McCarthyism] and reminding our Senate, ‘Look at the Constitution, look at the very First Amendment. What does it say? It says we prize, above all else, the right to think, speak, to write, as we will, without Big Brother over our shoulders’,” she said in a 2011 interview. “My notion was, if lawyers can be helping us get back in touch without most basic values, that’s what I want to be.”

But as one of only nine female students in her 552-strong class at Harvard Law School, she quickly realised that she would face an uphill battle. This put her on track not only to become a feminist icon, but to become a voice for the few.

“Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so,” Index on Censorship magazine’s outgoing editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley wrote in her most recent editorial, not knowing then that RBG’s was to die the following week.

As a Supreme Court Judge, her dissenting opinions (which opposed the majority views that gave rise to judgements) became legendary. The fact that dissents do not carry the weight of the law did not dissuade Ginsburg from putting forward extensive opinions.

“Dissents speak to a future age,” she explained. “But the greatest dissents do become court opinions and gradually over time their views become the dominant view. So that’s the dissenter’s hope: that they are writing not for today, but for tomorrow.”

Ginsburg knew how to use her voice, but she also knew when to use it. “In every good marriage, it helps sometimes to be a little deaf,” she often told students, repeating the advice offered to her by her mother-in-law on her wedding day. It was advice that she followed assiduously, she said. “Reacting in anger or annoyance will not advance one’s ability to persuade.”

She often moulded her silences into thoughtful pauses. “This can be unnerving, especially at the Supreme Court, where silence only amplifies the sound of ticking clocks,” wrote Jeffrey Toobin, who profiled Ginsburg for the New Yorker in 2013. But her considered interludes likely amplified her voice too.

Ginsburg also understood how to express herself in other ways. In her later years at the Supreme Court she began to accessorize, wearing a golden flower-like crochet collar on days where she would announce a majority view, and a black beaded collar for dissents.

She apologised after criticising Donald Trump in July 2016, saying that as a judge her comments were “ill-advised” and that she would be “more circumspect” in the future. But her decision to wear her so-called “dissenting collar” the day after Trump’s election spoke volumes nonetheless.

Ginsburg’s respectful and dignified expression, her consensus-building approach, and her mission to uphold women’s rights, alongside other fundamental freedoms, made her an antidote to the Trump Era.

At a time when it seems so crucial, Ginsburg inspires us to choose our moment – and our words – carefully, and to stand up for those who need our support. And, when necessary, to fearlessly diverge and wear our dissent with purpose.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Sep 20 | Art and the Law, Free Speech and the Law, Hate Speech, Index in the Press, News and features, Statements, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114965″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Heavy fines for social media companies who fail to act on online abuse and hate speech will have a negative effect on online expression, according to Index on Censorship CEO Ruth Smeeth.

Smeeth was taking part in a discussion on the proposed Online Harms Bill with the Board of Deputies of British Jews, a group that acts as a forum for members of the country’s Jewish community, along with shadow home secretary Nick Thomas-Symonds and Tottenham MP David Lammy (see top).

“Self-regulation has not really been effective,” said Smeeth. “[But] if we fine heavily they will be so conservative with what they allow on the platform.”

The discussion was called after rising incidence of anti-Semitism in the UK. Between January and June, 789 separate incidents of anti-Semitism were logged, up 4% on the previous year.

The proposed Online Harms Bill – still in its white paper stage – aims to force social media companies to regulate their sites in order to clamp down on abuse and harmful speech. The legislation is in line with a similar ruling in Germany introduced in 2017, where social media companies can face fines of up to €50 million.

Smeeth, herself a victim of online abuse, expressed her support for the bill as a way of tackling illegal hate speech, but suggested that alterations need to be made so that overly heavy fines do not cause social media companies to over-regulate.

“There are young people who have not been able to access counselling services having self-harmed,” she said. “They are using online forums to talk about their pain sometimes in very explicit language to support groups.”

“They would not be able to do so under this legislation.”

Clause 3.5 of the white paper draft will ensure that not just illegal hate speech can be shut down, but also what the legislation deems ‘legal but harmful’.

“The idea that we have something that is legal on the street but illegal on social media makes very little sense to me,” she said.

In 2019, Index made a submission to the white paper consultation, stating: “The focus on the catch-all term of ‘harms’ tends to oversimplify the issues. Not all harms need a legislative response.”

The law in Germany has since been criticised by Human Rights Watch and said it sets a precedent that will turn private companies into ‘overzealous censors’.

Shadow home secretary Thomas-Symonds is keen to have an independent regulator and feels the time for self-regulation has ‘long passed’.

He said: “We need a statutory duty of care and an independent regulator that has teeth. It has to have that power to levy particular penalties when social media companies are simply not doing what they should be.”

Lammy added that the key to curbing online hate speech towards minorities and anti-Semitism was the Online Harms Bill.

“You are not a civilised democracy if you do not protect minorities,” he said. “Until we have dealt with this issue nationally, we will not have fully dealt with it.”

In June, Lord Puttnam – Chair of the Lords Democracy and Digital Committee – warned that the bill may not come into effect until late 2023 or early 2024.

The full Index issued response to the white paper can be read here.

[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”38952″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

British-Canadian writer Lisa Appignanesi has found lockdown a difficult time to write, but despite this she has created a new short story exclusively for Index.

British-Canadian writer Lisa Appignanesi has found lockdown a difficult time to write, but despite this she has created a new short story exclusively for Index.