11 Aug 20 | China, Hong Kong, News and features, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Since the introduction of the National Security Law on 30th June basic human rights in Hong Kong have been under constant attack. Democracy movements have been forced to disband, Occupy leader Benny Tai was sacked from his position at Hong Kong University, news outlets have been raided by the police, peaceful protest has been all but banned and a new ‘approved’ media policy implemented. In the last week alone we have seen nine journalists arrested, including the founder of the Hong Kong news outlet Apple Daily Jimmy Lai, and a freelancer for ITV news Wilson Li.

This is a heartbreaking attack on a population which is proudly democratic and cherishes core human rights. Index was established to shine a light on repressive regimes and we will continue to highlight the abuses happening in Hong Kong by the Chinese government. We won’t be silent and we stand with the people of Hong Kong. We call on the British government to do the same; they need to intervene as a matter of urgency to protect the universal human rights that were enshrined in the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong signed in 1984. Every action by the Chinese government in recent weeks has broken both the spirit and the letter of this agreement.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

07 Aug 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114499″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]A year ago, on 5th August, Narendra Modi’s government in India unilaterally changed the status of the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir, revoking most of Article 370 which had given the region a level of autonomy and protection for 65 years. This single action has led to a year-long lockdown and curtailing of nearly every human right for the people of Jammu and Kashmir. The internet was switched off, phone lines were turned off, public gatherings were banned including for prayer, a curfew was instigated and the Indian army was deployed in significant numbers.

The situation on the ground has been devastating and it’s been almost impossible to get information to the Kashmiri diaspora about whether their friends and families are safe. For 213 days, you could not access the internet. And only after an international outcry were the approximately 300 journalists working in Kashmir given access to the internet via just a handful of official computers (in Srinagar, for example, CNN reported that the city’s journalists had to queue for hours to use just one of four computers with an internet connection for less than 15 minutes). Local media has been significantly restricted with huge pressure being placed on media outlets to only print the government line. The situation worsened just weeks ago, when the Indian government introduced a new media policy which has basically given carte blanche to the government to take action against any journalist or media organisation who operate in Kashmir if they don’t like what’s published.

Even in these circumstances journalists have remained in post, adamant to report on what is happening on the ground and the impact on the community – how people are surviving under such harsh circumstances. They have gone to extreme lengths to get news out, such as travelling to Delhi to access the internet. One Kashmiri journalist, Bilal Hussain, revealed in a recent interview with Index that in order to get video interviews to his editor in Paris, he would put them on a memory stick and give them to a friend who was travelling to the USA, and he sent it on from there.

These journalists did what only journalists can do, they shined a light where there was only darkness. They exposed the actions of a government that had moved against its citizens and they tried to tell the world.

This has not been without a huge personal cost though. Journalists have been harassed and in at least three cases arrested by the Indian authorities for doing their job. Masrat Zahra, a freelance photojournalist, Peerzada Ashiq from the Hindu newspaper and Gowhar Geelani, a renowned author and journalist, have all been arrested for crimes related to their journalism.

These journalists, these people, represent the front line in the fight for free speech. Their work, covering one of the most contentious areas of the world, ensures that the actions of government are not without consequence. They have made sure that the world knows and they have given hope to the people of Jammu and Kashmir. It’s our job to make sure that they do not stand alone and we won’t let them down.

The Autumn issue of Index has a dispatch from Kashmir about the challenges of working in the region as a journalist. Click here for information on how to read the magazine. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_btn title=”DONATE” color=”danger” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fdonate||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

06 Aug 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A screenshot of Merdan Ghappar from the video he filmed on his phone from a Chinese prison

In a video clip that went viral yesterday, Uighur model Merdan Ghappar doesn’t speak. But he doesn’t need to – the footage says enough. Shot by Ghappar himself from inside a prison cell, he moves the camera with one hand and reveals his other to be handcuffed to a bed. Ghappar is confined to a tiny room with mesh and bars on a window. His clothes are dirty as are the walls, and his face carries an expression of anguish and exhaustion.

Ghappar is incarcerated in one of China’s notorious prisons for Uighurs, the Muslim population who live in the far western province of Xinjiang. The Uighurs, with their Islamic faith, Turkic language and ties to the cultures of central Asia, have long been viewed by the Chinese state with suspicion and have faced discrimination. Following two brutal attacks against pedestrians and commuters in Beijing in 2013 and in Kunming in 2014, which were blamed on Uighur separatists, this suspicion has morphed into systematic oppression.

Estimates suggest more than one million Uighurs are now incarcerated in a network of prisons across the region. China initially denied the existence of the prisons, then acknowledged them but said they were re-education camps established to counter extremism in the province. The state denies Uighurs are being used as forced labour and denies rumours of torture and other abuses. The camps are also winding down, the state has recently said.

It can be hard to probe the official Chinese party line: foreign media is pretty much banned from Xinjiang. Reporters who have been there have found their visas revoked, such as Buzzfeed’s China bureau chief Megha Rajagopalan, who was forced to leave China in 2018. Rajagopalan had reported extensively on the crackdown in Xinjiang. When media is allowed in, as the BBC has been, the visits are highly controlled and staged.

But with each passing week and month evidence that directly contradicts the party line finds its way into the outside world; shipments of human hair products from Xinjiang reach New York; drone footage of rows of people queuing, shackled and blindfolded, for trains appears; testimonies of sterilisation of Uighur women emerge. And now Merdan Ghappar’s video. It might be the most significant piece of evidence yet.

Sure it does not come close to showing the real horror of the camps, but it does something else. It personalises the Uighurs’ plight. We see his face; we look into his eyes. And through his video and the reports that have emerged around it we learn his own, unique story.

We know that Ghappar studied dance at Xinjiang Arts University and worked as a dancer before he became a successful model. We know that in 2009, he moved away from Xinjiang in search of other opportunities in China’s wealthier eastern cities. We know, from his relatives, that he was told to downplay his Uighur identity and refer to his facial features as “half-European” if he wanted to get ahead in his career. And we know that he was also apparently unable to register the apartment he bought with his own money in his own name, instead having to use the name of a Han Chinese friend. We know that throughout this period Ghappar was in regular touch with his uncle, Abdulhakim Ghappar, who fled China after his activism in Xinjiang made him a target (in 2009, for example, he handed out flyers ahead of a large-scale protest in the city of Urumqi), and that while his uncle says Ghappar is not political, his ties to his uncle might explain why he became a target.

We know that in August 2018 he was arrested and sentenced to 16 months in prison for selling cannabis, a charge many believe is false. We know he was released in November 2019, but that soon after police told him he needed to return to Xinjiang to complete a routine registration procedure and that there “he may need to do a few days of education at his local community”.

We know that on 15 January, his friends and family brought clothes and his phone to the airport where he boarded a flight and was escorted by two officers back to his home city of Kucha. And most significantly, we know that he somehow managed to not only keep, but use his phone and from this reveal some details of his own incarceration (initially in a squalid, unsanitary prison jail where he was surrounded by the sounds of other inmates screaming; later in the facility shown in the new video he says his “whole body is covered in lice”).

But we don’t know where he is today. Ghappar’s messages have stopped. No one has heard from him and authorities have not provided notification of his whereabouts.

There is an increasingly loud chorus of calls for what is happening in Xinjiang to be labelled a genocide – and this could definitely change how the international community responds to the situation. But as history has proved even if it is officially termed a genocide will it force us, on an individual level at least, to act differently?

Comparisons to the Holocaust come easily and one line of defence there, which has come up again and again, is that people didn’t act because people “didn’t know”. But that’s historically contested given how ubiquitous the camps were. There was a reason people on arrival at Auschwitz tried to rouge their cheeks to appear healthy – they knew.

What some historians have argued, though, which could partly explain the inaction of many, is that while people might have known, they didn’t understand. The truth was simply too abhorrent to fathom. And without understanding they didn’t truly know.

And that’s why Ghappar’s video and story is so important. As was the case with Anne Frank, and indeed recently with George Floyd, sometimes you need a face, a singular experience, to relate to the suffering of the whole. Stories that are granular touch people in ways that the bigger picture cannot always. News of the ill treatment of Uighurs is not new and yet within hours of Ghappar’s video circulating, crowds began protesting outside the Chinese Embassy in London.

Ghappar has made the Uighur suffering feel much more real and more personal. He could be our brother, our son, our neighbour, our friend. He’s not just a number or a news headline; he’s a face and a name. Let’s learn that name and tell his story. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

04 Aug 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114463″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]“Journalists are very, very afraid. They are being seen as enemies of the state because of this surveillance, because of their political activism, opposition politicians are afraid, everybody is afraid of the government,” said Issa Sikiti da Silva, a journalist from the Democratic Republic of Congo who has travelled to and reported from many countries across Africa. Sikiti da Silva was speaking at the digital launch party of the Index on Censorship summer magazine, held on Friday 31st July.

The summer issue looks at the ways in which our privacy is being increasingly infringed upon in the coronavirus era. From health code apps in China dictating when people can leave their homes to poor digital literacy levels in Italy (and beyond) leaving people vulnerable to exploitation, the magazine takes a broad view.

Sikiti da Silva was joined by Turkish writer and journalist Kaya Genç and Spanish journalist Silvia Nortes. The panel was chaired by Rachael Jolley, editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine.

“The state is tapping our phones, the state is following us into Starbucks branches…they’re all around you. But with online surveillance it’s impossible for me to know whether someone from the Turkish embassy in Britain is watching this event or someone from the intelligence agency in Turkey is watching this event. So it puts us on the spot, this new age of digital surveillance, and that’s what my piece was about for the new issue of Index,” said Genç as part of the discussion.

When asked if recent increased surveillance, in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, was a cause for concern in terms of media freedom all panellists said it was.

Genç explained how digital surveillance is a more insidious form of government espionage, which is causing a fresh set of worries: “In a country like Turkey the state is a very palpable thing, you see it on the street…and its presence makes it a bit vulnerable because we are the one that is scrutinising that visible entity. But now it seems with apps like Life Fits Home [a Covid-19 tracing app], the state became invisible and its surveillance powers have increased.”

Nortes discussed how, in Spain, reactions to Covid-19 tracing apps and state surveillance have fallen along generational lines: “Younger people are more open to using this kind of app because, of course, they are aware that we live in a hyper connected society.”

She suggested that historical precedents may have imbued older generations with a different perspective on security around their personal information: “They feel more reluctant to give in their data and I believe this is connected somehow with [General] Franco’s dictatorship.”

She continued: “The surveillance of these years really has something to do with the concept of private life that older generations have in Spain.”

Sikiti da Silva painted a picture of Africa as a continent in which dictators continue to rule.

“Journalists are being watched over [by the state] and by the time they have enough evidence then they will move on you or arrest you or kill you whatever they want to do with you.”

When Jolley asked if anyone was fighting back against this kind of oppression, Sikiti da Silva was blunt in his reply. He said that without money or power, there is no fighting back. “What people do mostly is to run away. In Africa we only have one solution. You run away…that’s all you can do. You just leave the country before it is too late.”

This has informed Sikiti da Silva’s travels around Africa: “Where there is media freedom I stay. Where there is no media freedom I do two or three stories, then I run away.”

Nortes said that the national security force in Spain is working on detecting ‘fake news’ which could “generate hostility toward the government’s decisions”.

“This is targeted surveillance, they’re just looking for news that could affect in a bad way the government’s management of the pandemic.” This is a trend that Index has been reporting on as part of a global project to map media freedom during the coronavirus crisis.

“We need to be sure that once the pandemic is over we will have the same rights that we had before,” added Nortes.

Click here to read more about the current magazine [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

03 Aug 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103857″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Just 37% of UK academics have said they would feel comfortable sitting next to someone who, in relation to transgender rights, advocates gender-critical feminist views, a new report on academic freedom in the UK has revealed. The report by Policy Exchange, released today, is one of the largest representative samples of UK- based academics carried out in recent years. It explores the concern that strongly-held political attitudes are restricting the freedom of those who disagree to research and teach on contested subjects. The report also proposes what might be done, in the form of legislation and other measures, to ensure that universities support intellectual dissent and all lawful speech is protected on campus.

Protecting academic freedoms was one of the founding principles of Index in 1971 and continues to be an area that we are concerned about, so we very much welcome the debate inspired by this report and look forward to hearing from other voices.

Read Index CEO Ruth Smeeth’s foreword for the report:

“It was recently suggested to me that I might have been a target of a little too much free speech in recent years, so it could be viewed as strange that I am so passionate about protecting our collective rights to free speech. But honestly, I have a romantic view of one of our most important human rights.

Free speech should be challenging; it should drive debate and ultimately force all of us to continually reflect on our own views. Free speech should manifest in different ways in different forums. In literature, it should drive our intellectual curiosity about the world around us. In journalism, it should shine a light on the powerful and ensure that the world is informed. And in academia, it should drive debate about the status quo demanding that we continually evolve as a society. It’s only by the guarantee of this core human right that we can ensure that we are the best that we can be, that our arguments are robust and that they can sustain criticism. Simply put, debate makes us better as individuals and as a society, it also makes our arguments more rounded and demands of us the intellectual rigour that drives positive change.

That’s why this publication is so important. Throughout our history, we’ve seen a cyclical approach towards academic freedom, but the reality is that only when our centres of learning are truly independent have we thrived as a society. This research isn’t about determining who is right or wrong, or whose voice is more valuable on any given issue but rather the proposals are designed to ensure that there is still a free and fair debate on our campuses. That the academic freedom that we all should cherish is given the protections it needs. It does the country no good if our educators, our academics, our scholars and most importantly our students feel that they can’t speak or engage without fear of retribution.

We all know that legislation is not a panacea to the chilling effect of what is happening in our public space for anyone that challenges the status quo. It can’t and won’t change the culture on campus but what it can do and what this document squarely aims to do is inform, engage and start a debate about what should be important to us. As a society, we need to have our own national conversation about our core human rights and how they should manifest in the twenty-first century. We need to decide collectively where the lines should be between hate speech and free speech, between academic inquiry and ‘research’ designed to incite, between journalism and purveyors of fake news. This research is an important part of that conversation.”

Please read the report in full here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

31 Jul 20 | News and features, Opinion

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

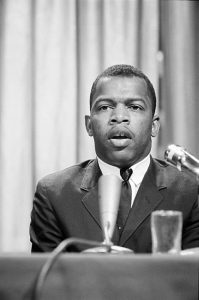

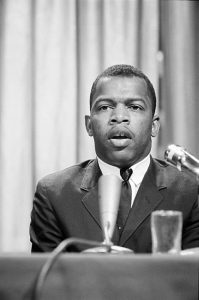

Civil rights activist John Lewis at a meeting of American Society of Newspaper Editors, 16th April 1964. Credit: Marion S Trikosko, US News and World Reports

This week saw the funeral of the civil rights legend, Congressman John Robert Lewis. The word hero can be attributed all too easily but that’s simply not the case when you use it to describe John Lewis. In 1961, he was one of the first freedom riders, refusing to sit at the back of the bus. He one of the “Big Six” organisers and the youngest speaker at the March on Washington in 1963. In 1965 when crossing Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, he became the face of police brutality as he was beaten until bloody. He led the campaign to register millions of people to vote in the 1970s. And in 1986 he was elected to the US House of Representatives representing Georgia’s 5th Congressional District, a role he held until his death on 17th July 2020. He did all of these things with a level of personal dignity that was inspirational.

John Lewis wasn’t just an American hero – he was a living legend and a global citizen. He inspired all of us who are passionate about human rights and he led the charge for equality – as a peaceful non-violent movement. And on every step of his journey he got into “good trouble”. He was never afraid to use his voice to fight for others, to fight for justice, to fight for fairness, and for that every single one of us owes him an eternal debt of gratitude.

You may be asking why I am using my weekly blog on free speech to celebrate the life of one of my heroes. And of course, I am taking slight liberties. But the civil rights movement used their right to free speech, free association and freedom of the press to make the world stop and listen. They used every right outlined in the First Amendment to make themselves heard. Every possible weapon in their peaceful arsenal to make our global community a better place.

John Lewis worked tirelessly, hand-in-hand, with Dr Martin Luther King Jr, exposing discrimination, shining a light on injustice and using such powerful oratory as part of their protests that the world could not ignore their plight. Our civil rights heroes taught every other equality movement the power of language, of storytelling, of the spoken and written word and the vital importance of the free press. In other words, they didn’t just rely on free speech to achieve their objectives, they celebrated it and that’s why I’m such a passionate defender of it.

I fear that the current climate of increasing polarisation in our public conversation means that we are forgetting the lessons of the heroes and heroines of the civil rights movement. John Lewis wanted to win the argument to make a difference and he did just that. He exposed every injustice and absurdity of the Jim Crow laws; every time he was arrested he made sure that the media knew about it and he told his story – to prove he was right, both morally and legally. We need to relearn his methods and we need to re-embrace storytelling – making sure that we have free speech for a purpose – to make the world a better place.

In his words: “Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_btn title=”DONATE” color=”danger” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fdonate|||”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Jul 20 | Index Shots, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VpbIyNZ7WKI”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You might also like to watch” category_id=”41199″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Jul 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”104009″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]There are so many ways you can infringe on someone else’s free speech and obviously some examples are much more egregious than others. Some instances undermine the very premise of this most basic of human rights whilst others are so personal that they create a chilling effect on people’s ability to participate in their own national conversation.

This week, we’ve been able to witness everything on the spectrum from people being trolled for taking a stand against racism to Maria Ressa facing yet more legal action in the Philippines. There is also the awful case of one of the key witnesses in the Daphne Caruana Galizia murder trial being found with a slit throat on the morning they were due to give evidence.

Each of these issues demands their own platform, their own space to explore what is happening and what it means both for the individuals concerned and for the societies we live in, whether they be physical or virtual. Context and analysis are key; collectively we need to understand what each of these cases mean for our society and where they fit into the current debate on free speech.

Index was launched, nearly half a century ago, to be a voice for the persecuted, giving space to those people who could not be published elsewhere. We were also tasked with shining a spotlight on repressive regimes, exposing authoritarian attacks on free speech and celebrating those people who were brave enough to speak out. And just as importantly we were established to ensure that the UK remained a bastion of hope for those people who lived in societies which didn’t respect their core human rights. These three pillars remain at the core of what we do and who we are.

Index will always be a home for people who want to be heard. We will always stand against authoritarian and repressive regimes to protect our collective free speech. And we will stand against anyone who seeks to use their power to silence those less powerful. Our role is to expose, to listen and to stand with some of the bravest people in the world so that their voices can be heard. So that you can hear directly from them

To do this we need your help – please take a minute and, if you can, donate to Index so we can keep doing this vital work.[/vc_column_text][vc_btn title=”DONATE” color=”danger” size=”lg” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fdonate|||”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE TO READ” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Jul 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114332″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Should President Andrzej Duda continue supporting all key policies of the United Right currently governing Poland, media freedom and the independence of journalists will likely be curtailed.

During his first term as the president of Poland, Duda, formally independent, proved his loyalty to the Law and Justice (PiS) party on numerous occasions. For example, in 2016 he signed a law that gave the government greater control over state broadcasters.

State broadcasters have since become a propaganda machine for the governing majority. Many reports on the general elections held in Poland in 2019 and on the presidential elections in 2020 highlighted their lack of pluralism. But at least privately-owned media has remained an alternative source of information for a significant part of the population in Poland. But even that is not safe.

Over the years, foreign-owned media has been criticised as being anti-Polish and these criticisms grew louder during the presidential campaign. Duda implied that Germans wanted to influence the outcome of the election after the popular German tabloid Fakt published a story saying that Duda had pardoned a man convicted of sexual abuse of his daughter. Duda also unleashed an attack against Philipp Fritz, Warsaw correspondent of German newspaper Die Welt, accusing him of promoting the opposition’s campaign.

“Today, ladies and gentlemen, we have yet another German attack during these elections,” Duda said.

These remarks by the president, as well as other comments by the government officials, have raised concerns among journalists in Poland that after Duda’s win, the governing majority will try limiting independent media and journalism. The concerns are that first state-owned companies will try to buy-out key TV, radio, print commercial media from foreign owners. Second, the profession of journalists, now free, might be regulated, opening up a possibility to activate disciplinary proceedings against journalists and limit who can be a journalist in Poland.

And our fears are already feeling justified; since Duda’s re-election top public servants and high-profile PiS politicians have announced plans to take on commercial media and independent journalists.

Who will protect journalists? As president of Poland Duda has the power to veto legislation and issue motions to the Constitutional Tribunal to verify if the adopted laws conform with the Constitution. But on many occasions he has shown his loyalty to PiS. Since they came to power in 2015, they have waged a campaign to take control of the judiciary in open defiance of the law. By May 2018 they had managed to gain direct control over the Constitutional Tribunal and the National Council of the Judiciary. A triumvirate has therefore formed between the government, the Constitutional Tribunal and the president, which has allowed fast-tracking key legislation and rubber stamping controversial policies targeted against judicial independence.

Duda’s victory in the presidential contest on 12 July 2020 opens up the possibility that this alliance continues. The next general election in Poland should happen no earlier than in 2023. The United Right camp has three more years to implement its desired policies.

I fear discouragement and the chilling effect on journalists the most. In Poland, as in many places elsewhere, the profession has become more precarious which in itself could be a discouragement for many young people interested in pursuing this sort of career. Add an increased political pressure, and people may start having doubts if it is all worth it.

We need independent, broad-minded, professional journalists more than ever. It’s the most critical time since 1989 and we need to improve standards of democratic debate. OKO.press is keeping up the good work and we hope to continue fulfilling our mission to offer in-depth journalism on topics of public interests to all of Poland, without a paywall. Hopefully we can continue well into the future, but it has never felt more in peril.

Anna Wójcik is a journalist at Polish investigative journalism and fact-checking website OKO Press. OKO are the 2020 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Journalism Fellow. Read more about them here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Jul 20 | News and features, Philippines

Index and the other 77 civil society and journalism organisations that make up the #HoldTheLineCoalition demand that the Philippines authorities drop a barrage of bogus tax and foreign ownership cases against journalist Maria Ressa and Rappler – the news organisation she founded.

“The prosecution of baseless financial charges and cases represents an attempt to use tax law and foreign ownership regulations as another weapon to criminalise journalism and silence Ressa and Rappler as threats to press freedom and democracy escalate in the Philippines,” said the #HoldTheLine steering committee. “We urge the government to drop all charges and cease and desist its orchestrated harassment campaign.”

The Coalition was formed after Ressa, a prominent Filipino-American editor, was convicted on a trumped-up criminal cyber libel charge in June.

The Coalition’s call for the dismissal of all tax and foreign ownership cases and charges comes as Ressa prepares to return to court in Manila on 22 July on a baseless criminal tax charge, amid concerns about a suspected Covid-19 outbreak involving the death of a worker at the Pasig Regional Trial Court where the hearing will take place.

Ahead of this appearance, this Court has an opportunity to quash the criminal taxation charge on which Ressa faces arraignment. The #HoldTheLine Coalition urges the state to immediately drop this charge and end the prosecution of the other charges and cases associated with it.

Convictions against Ressa in three related tax cases cumulatively represent prison sentences of 44 years. They hinge upon the bogus notion that Rappler’s parent company, Rappler Holdings Corporation (RHC), is not a holding company for a news organisation but rather a ‘dealer in securities.’

“Legal acrobatics – that’s what all these cases show. In order to charge me with tax evasion, the government reclassified Rappler as a ‘dealer in securities’ – we’re obviously a news organisation. It’s absurd!” Ressa said. “From inciting hate on social media to weaponising the law to using the full force of the state against journalists trying to hold power to account … it’s a war of attrition, tearing down trust and credibility. This is how democracy dies by a thousand cuts.”

The tax-related cases and charges are predicated on another suite of charges and cases connected to alleged foreign media ownership breaches designed to shut Rappler down. They cumulatively represent maximum prison sentences of up to 36 years.

Together with the criminal libel conviction, which is currently under appeal, and a second pending libel action, convictions in all these cases could theoretically lead to a century in jail for Ressa.

Further, the Coalition calls on the Pasig Regional Trial Court to conduct proceedings remotely on 22 July to ensure the safety of Ressa, her legal representatives, media and court staff amid the coronavirus pandemic. We note that in addition to this court being associated with what appears to be a deadly Covid-19 outbreak, Ressa was forced into lockdown following her appearance in June before a different court which was also the subject of a COVID-19 scare.

More than 10,000 people have signed a petition calling on the Philippine government to drop all cases against Ressa, her former colleague Reynaldo Santos Jr, and Rappler, and to cease attacks on independent media in the Philippines.

17 Jul 20 | Index Shots, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]On 5 July 2017, human rights defenders from a number of different organisations gathered on the island of Büyükada for a workshop on the protection of digital information.

On the third day of the workshop, ten of the attendees were arrested at gunpoint and later charged with aiding the Fethullah Gülen Terrorist Organization, which President Erdoğan blames for 2016’s failed military coup.

The Istanbul 10, as they became known, were released on bail on October 25th 2017, after 113 days in detention but then faced three years of court hearings.

On 3 July 2020, former Amnesty Turkey chair Taner Kılıç was convicted of membership of the Fethullah Gülen Terrorist Organization and sentenced to 6 years 3 months in prison.

Meanwhile, Özlem Dalkıran, İdil Eser and Günal Kurşun were convicted of assisting the organization and sentenced to 25 months, pending an appeals process which could last years.

As the sentences were announced, Index’s editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley spoke with Özlem Dalkıran.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/jFAojAdwiQk”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Jul 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114308″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]I think it’s fair to say that issues associated with free speech have been a recurring feature of our news in the last month, from the removal of Colston’s statue in Bristol, to the Hong Kong National Security law, to the very public debate on “cancel culture”. It seems a day doesn’t go by without a reference to free speech or someone pontificating on where the limits should be.

There are lots of things missing in the current conversation about free speech though – at least for me. The most crucial of which is why free speech is a core human right. Why does it matter if our voices are limited? If we can’t write or create art who does that hurt? If we don’t know what’s going on around the world – does it make a difference to our families?

I’m hoping that if you’re reading this then you share my view that being able to use our voices and to listen to each other gives us our humanity.

As a core tenet, our right to free speech has built the society that we live in – at least here in the UK. It has given us the literature which changes our perceptions of the world. Art that provokes emotion, academia which challenges the world as we know it and ensures that our society continues to develop and thrive. And of course, journalism which, on a daily basis, exposes the powerful and seeks to provide the ultimate scrutiny.

July 2020 has been an awful month to be a journalist in Britain. The BBC, The Guardian and Reach (the owner of the Daily Mirror and the Daily Express as well as numerous local and regional papers) have all announced redundancies. Meanwhile, the Archant group (which also own dozens of local papers) is desperately seeking a new buyer. Covid-19 is having a devastating effect on the media on which we rely to make sure that corruption is reported, that repressive regimes are exposed and that provides a platform to speak truth to power. So, if you don’t already, it’s time to subscribe to a newspaper to make sure that journalism as a profession survives the 2020s.

Freedom of journalistic expression is vital for our society and in an era of disinformation and counter-propaganda, reliable and constant sources of information have never been more important. If it wasn’t for investigative journalists then we would not know of the horrendous plight of the Uighurs who, as I write, are are being transported to concentration camps in the Xinjiang province. We wouldn’t know of the women who are being sterilised by order of the state and of the children who are being re-educated.

Journalists at their best shine a light in the darkness and their bravery and determination makes the world listen and forces governments to act. I pray that, even in the middle of this awful pandemic, we listen to those brave voices reported in our daily newspapers and stand with the Uighurs against what can only be described as acts of genocide.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”YOU MIGHT LIKE TO READ” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]