30 Jun 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”113563″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]The fear was palpable on social media. Days before Hong Kong’s National Security Law was passed people started to delete their Twitter accounts.

“It is already corroding our freedom and rights,” wrote Alex Lam, a reporter for Apple Daily, who remained on the platform.

The fear was felt by journalists. “I’m keeping a low profile” people told Index as they refused to be interviewed “on the record”. Soon the word “anonymous” appeared with great frequency on articles from the city.

And the fear was felt in the streets, as far fewer took to them to protest, in stark contrast to last year when threat of a similar bill saw millions on them.

The National Security Law, which Beijing announced in May and passed today, has already done exactly what it intended – it has paralysed pro-independence and pro-democracy advocates in the city.

The opacity of the law is part of its success. It criminalises secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces, but none of these have yet been clearly defined. Anthony Dapiran, a lawyer in Hong Kong and author of City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong, told Index that “no Hong Kong lawyer will be in a position to advise on the law and its impact with any certainty, which is clearly a concern for Hong Kong’s rule of law.”

Mainland China, of course, provides some clues.

“On the mainland, national security laws are routinely used to arbitrarily detain, prosecute and jail a wide range of critical voices, including journalists. Right now we have no guarantees beyond some vague assurances from an authoritarian one party state with a dismal track record of respecting press freedom,” a journalist told Index. The journalist works for a major global media organisation. They requested anonymity for fear of retaliation on themselves or their company.

Echoing their views, writer and Hong Kong resident Tammy Lai-Ming Ho wrote in a letter published yesterday on Index’s site that “we only have the worst case scenarios to look forward to”.

“A similar law has been used in mainland China to attack dissidents, including democracy advocates such as the late Nobel peace laureate Liu Xiaobo and human rights lawyers such as Wang Quanzhang, not to mention academics and labour activists who are not household names,” she said.

“For decades Hong Kong has been a major media hub for Asia. But international media will have to think long and hard about whether Hong Kong can remain a safe and viable place to host regional headquarters or major newsrooms. If foreign and local journalists start having to self-censor, watch what they write or who they interview, what talks they host or attend or which organisation they work for, then many organisations may well relocate to freer environments with stronger legal protections,” added the anonymous journalist.

David Schlesinger, former chairman of Thomson Reuters China, who lived in Hong Kong on and off between 1982 and 2017, concurs. He told Index:

“It will certainly affect coverage of Hong Kong itself. It’s been a completely free reporting environment, whereas now people will have to look over their shoulders. They will have to treat it like they would if they were reporting in Shanghai or Beijing.”

Schlesinger says local reporters will be most affected. Reporters from Ming Pao and Apple Daily, for example. But he also says it will affect where international news organisations base their headquarters. Schlesinger cites the case of Bloomberg. In 2012, while researching an explosive story on the wealth of incoming president Xi Jinping’s extended family, key members of Bloomberg’s normally China-based staff left Beijing and researched out of Hong Kong itself, and then, once the story blew up, moved to the territory as a safe refuge, something that now would be unimaginable.

One thing is clear: it deals a devastating blow to Hong Kong’s autonomy as promised under the “one country, two systems” framework, the terms of the former British colony’s handover to Chinese control in 1997 which were meant to last until 2047. Over the last week a meme has spread online by the city’s youth. It reads: “I expected to be older when 2047 came”. Beneath the humour lies sadness and desperation.

Chinese cartoonist Badiucao told Index: “The passage of the National Security Law in Hong Kong marks the end of a free city and may just as well open the curtain of the new Cold War between China and the world.”

For those who have been watching Hong Kong closely over the years the law has not come out of nowhere. In a special for Index on Censorship magazine in January 1997, just ahead of the handover on 1st July 1997, Index noted:

“Beijing’s strident policies on Hong Kong seems to be confirming some darker fears about the continued protection of freedom of expression after 1997. Over the past year the Chinese authorities have shown themselves to be concerned not with protecting the right to freedom of expression, about which they have grave misgivings, but with eroding it.”

Index has raised concerns periodically since. A major turning point was 2014 when Beijing issued a decision regarding proposed reforms to the Hong Kong electoral system that challenged Hong Kong’s political autonomy. The reforms sparked the Umbrella Movement. Back then, Index reported on how self-censorship had become “insidious” in the city.

“It’s a creeping, insidious type of thing. If you want to keep your job, you tow the line. I work with guys who are pro press freedom, but they are still censoring constantly,” said a reporter from a prominent local newspaper.

It wasn’t just self-censorship. The same article spoke of violent attacks on journalists who were critical of the Hong Kong and Chinese governments, including Kevin Lau, former chief editor of Ming Pao, who was stabbed in his back and legs as he got out of a car.

We reported on the forced disappearance of Hong Kong booksellers in 2015 and how the city had gone from a place that would publish daring, critical books on China to somewhere where editors said no.

Then in 2018 we investigated a novel intimidation tactic that was moving beyond Hong Kong. Specifically, threatening letters were landing on the doorstep of people in the UK who were critical of the human rights record in Hong Kong. And not just them, their neighbours were receiving letters too. Hong Kong native Evan Fowler, himself a recipient of threatening letters, told Index how Hong Kong was “a city being ripped apart”.

2018 was the same year that the FT journalist Victor Mallet had his working visa denied after chairing a talk with Andy Chan, a pro-independence political activist. This marked the start of more aggressive action towards journalists at international media, who until then had mostly been shielded from the threats that their local counterparts had faced. Two years on and, as Index has covered in its map on media violations during Covid-19, China recently expelled a handful of journalists at the New York Times, Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal whose credentials were up for renewal this year. In an unprecedented move, they were not allowed to work from Hong Kong or Macau either.

But no matter how bad it has become in the city over the years, it has always remained far more free than across the border in China. The city was not, and is still not, behind the Great Firewall. The city is a place where until this year large-scale Tiananmen Square vigils are held, a place that even had a museum dedicated to the massacre (read our article with the curator here). It is a place where millions come out year after year to fight for their freedoms.

“Protest remains a fundamental part of the Hong Kong identity,” said Dapiran, who believes that this “spirit will continue”.

And even as peaceful protest turned into scenes of police violence, the demolition of freedoms was not a given. Until now.

Hong Kong matters. It matters to the more than seven million who live there. The offer by UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson to grant visas to three million people from Hong Kong is a welcome gesture, but moving is not an option for most. What of those who speak little or no English? What of those without the financial means to move abroad? What of those who have elderly relatives in Hong Kong? What of those who see Hong Kong as their home?

Hong Kong matters to the 1.4 billion just across the border. If people in Hong Kong can’t speak up then what hope is there for those in mainland China?

“Throughout the decades Hong Kong has always been a clearing house for information to make its way back into the mainland news ecosystem,” Louisa Lim, who reported from China for a decade for NPR and the BBC, told Index.

Last year, the Chinese journalist Karoline Kan wrote in the magazine that despite the best attempts by the Chinese government to block news on the Hong Kong protests word was still reaching people in China. And the news was sending a powerful message. These messages end if Hong Kong is silenced.

And Hong Kong matters to the rest of the world. On 27 January a cartoon by Niels Bo Bojesen appeared in Denmark’s Jyllands-Posten that portrayed coronavirus particles in place of the stars on the national flag of China. The Chinese embassy in Copenhagen demanded a public apology. Fortunately Danish politicians were vocal in their defence of the paper. Will we continue to see such defences of free expression? Or will acquiescence when it comes to Hong Kong embolden China further and erode our resilience?

Ma Jian wrote in the 1997 Index special that “from 1 July, the drift begins: Hong Kong becomes a floating island, migrating on the map.”

Today is a terrible day, but tomorrow is a new one. We all need to make sure that we raise our voices – individually and collectively – so that Hong Kong remains an island both spiritually and physically separated from China’s mainland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Jun 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114095″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]The Covid-19 pandemic has been largely contained in Hong Kong, with only about a dozen community cases over the past two months and all imported cases detected and isolated upon arrival. I was beginning to allow myself to feel less depressed about the situation in the city, even though I continued to worry about how coronavirus was affecting the rest of the world. And then, in late May, Beijing announced the National Security Law for Hong Kong, bypassing the city’s Basic Law and Legislative Council.

The law came out of nowhere, with the stated targets of so-called secession, terrorism, subversion, and collusion with foreign governments. When did they start planning it? Who was involved in drafting it? How is it going to be implemented? It was a devastating day in Hong Kong when the news was released, and I am certain many were plunged into yet another emotional and psychological abyss. I myself felt angry, helpless and wistful for ‘simpler’ days when the news wouldn’t break your heart or make your blood boil on a daily basis.

If last year’s extradition bill, which was withdrawn in September after mass protests, didn’t drive people away, the national security law has already sufficiently frightened many to make plans to leave. Whatever confidence they might have had in the city’s democratic future has been crushed. Like a skull being smashed against the wall by the Chinese Communist Party. The opacity of the law, combined with the severe sentencing—the city’s sole delegate to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee Tam Yiu-chung has even suggested life sentences for some infractions—are making people relocate. Those who have no means to leave are like silent lambs under knives that can fall at any time.

The National Security Law is particularly chilling for the following reasons: the speed of its introduction; the top-down approach, which has completely disregarded the opinions of people here; the way it has been cloaked in secrecy for spurious reasons – not even Hong Kong’s puppet chief executive Carrie Lam has seen the text, and nobody will until it is passed. The lack of means for Hongkongers to express their views and push back—and the inevitability of the law being passed (although I have to admit I still harbour some naïve belief that some miracle might happen and reverse the situation). Most worryingly, there is the way a similar law has been used in mainland China to attack dissidents, including democracy advocates such as the late Nobel peace laureate Liu Xiaobo and human rights lawyers such as Wang Quanzhang, not to mention academics and labour activists who are not household names. I fear we only have the worst case scenarios to look forward to.

What we are witnessing is the rapid evisceration of “One Country, Two Systems”, the principle by which Hong Kong has been governed since the 1997 handover. By removing the legal firewall between the mainland and Hong Kong, Beijing is reneging on its pledges in the 1984 Sino-British Declaration. While Hongkongers have long come to distrust the Chinese government, this is the final betrayal, after their concerns voiced repeatedly in popular protests, and elections in 2016 and 2019, have been dismissed.

This also has implications for a world that is turning increasingly authoritarian. And China, with its overseas initiatives such as Belt and Road, is pulling other countries further into its ambit and dependency on it. The Chinese government does not hesitate to interfere in other countries, demanding publishers and organisers of events withdraw items that displease it, such as a recent photography exhibition in Belfast, where the Chinese consulate requested a photograph of the Tiananmen “Tank man” be removed (the request went unanswered). As China’s economic heft in other countries increases, such demands and interference will only become more common.

History has shown how precipitous change for the worse can be. Countries in the West and elsewhere have long accommodated China out of economic pragmatism; only now are many of them waking up to the dangers of appeasement. The Chinese Communist Party has no intention of yielding any power, either at home or abroad, and what it has done in Hong Kong with the National Security Law should be a wake-up call for countries everywhere.

Monday 29 June 2020[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jun 20 | Volume 49.02 Summer 2020, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Why don’t we learn that censorship and lack of trust in society puts us all at risk, particularly in times of crisis, asks Rachael Jolley in the summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine”][vc_column_text]

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.

Censorship by the Chinese state that stopped the rest of the world finding out what was happening as early as it could have.

Surely this is one of the most compelling arguments against censorship that we have seen in our lifetimes. Showing that if we know about a risk, we are able to discuss, to explore, to research, to prepare, and to take measures to avoid it.

As Covid-19 spread through the world, the parallels with World War I and the Spanish Flu were obvious. Here was a dangerous disease that many countries refused to acknowledge, that doctors were prevented from speaking about and that, for a time, the public had no knowledge of.

In 2014, I asked leading public health professor Alan Maryon-Davis to write about World War I and the flu epidemic for this magazine, a lesson from history for today. He wrote: “We also know that it was the deadliest affliction ever visited upon humanity, killing at least 50 million people world- wide, probably nearer 100 million, several times more than [the] 15-20 million killed by the war itself – and more in a single year than the Black Death killed in a century.”

Maryon-Davis identified three weak links that could have incredibly dangerous consequences in the reaction to a pandemic.

One was that health workers on early cases might worry about reporting it (self- censorship); the second was that governments would worry about political/cultural consequences (political censorship); and the third was that a cloak of secrecy might be thrown over it (pure censorship). Check, check, check. It’s happened again.

Lessons learned from history? Practically nil.

As we move through the tracking phase of this pandemic, we need to recognise that public trust is an essential part of any response, and that public will comes from a belief in society – and a belief that it will act for the public good. Trust also comes from a belief that your government will not collect private information about you and use it without permission, or to your detriment.

Historically, those who fought for freedom of expression and speech also fought for the right to privacy: your right to keep information private – such as your religion or sexual orientation – and the right for you not to have an illegal search of your private papers or your home. Those rights came together in the US constitution because those who wrote it knew what it was like to be in a minority or a protester in a country which oppressed those who did not conform.

They fled those countries to find more freedom, and they sought to create legislation that would mean others could choose to be different, or to express offensive or difficult ideas. That might sound ridiculously ideal- istic, and of course it was – there are plenty of holes people can pick in the reality of US society – but those ideas are strong, and valid for today.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”In Turkey there are independent thinkers who believed that home was the last refuge where they could criticise the government”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The right to privacy (and with it the right to express a minority opinion) is often endangered by legislation that is introduced without due process during times of war or crisis.

And it is against this backdrop that activists, journalists, academics and others began to worry that during this pandemic we are, with- out really considering the consequences, giving away our privacy.

Governments around the world have often responded to the Covid-19 situation with diktats that remove an element of democratic governance, or threaten hard-fought-for freedoms, with very little opportunity for public debate.

India’s Justice H.R. Khanna, among others, famously warned that governments use a crisis to ignore the rule of law. “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

This feels like wisdom that’s fitting for the current fractured moment.

In Turkey, there are independent thinkers who believed that home was the last refuge where they could criticise the government or talk about a difference of opinion from the mainstream. The introduction of the Life Fits Home app could mean a severe erosion of that private space, as once they have input their ID numbers, the government will know exactly who is where, and with whom.

As Kaya Genç outlines in his article on p50, the question is: can they trust an autocratic state which could save their lives via contact-tracing not to come after them later for political reasons?

This is similar to the question being asked in Hong Kong by those who protest against the ongoing erosion of the freedom which ensured it was a very different place to live from China in the last two decades.

During the pandemic, there have been discussions about the dangers of sharing personal information with the government, and one Hong Kong citizen we interviewed for this issue outlined why.

“Of course, we’re willing to do what we can as a collective to stop the spread of Covid-19,” she said. “But the point is, we have no trust in the government now. That’s why I don’t want to trade my information with the government in return for a few face masks.”

Another said people were worried about an app that they were required to download if they left the city and wanted to return, asking: “Who knows what they’ll do with our data?”

Some governments have put in place legal checks and balances to give people more confidence, and to offer assurances that data will not be used for other means.

In South Korea, a law was amended after the 2015 Mers outbreak to give authorities extensive powers to demand phone location data, police CCTV footage and the records of corporations and individuals to trace contacts and track infections.

As Timandra Harkness outlines on p11, that same law specifies that “no information shall be used for any purpose other than conducting tasks related to infectious diseases under this act, and all the information shall be destroyed without delay when the relevant tasks are completed”.

In Australia, legislation restricts who may access data gathered by a Covid-19 app, how it may be used and how long it may be kept.

Other countries have done much less to offer legitimacy and transparency to the data- gathering processes in which they are asking the public to participate.

In the UK, for instance, there has been no sign of legislation outlining any restrictions on how data captured by its track and trace system, or expected Covid-19 app, will be restricted from other use, or even stopped from being sold on to third parties.

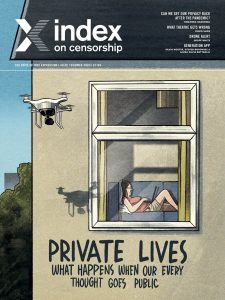

Requests to ask the public to add apps such as these come at the same time as we see rising numbers of drones being used to invade our private spaces, and potentially to track our movements or actions.

We also see a dramatic, mostly unregulated, increase in the use of facial recognition around the world, again taking a hammer to our rights to privacy, and ramping up surveillance.

US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote in the 1920s of those who wrote the early laws of his land: “They knew that order cannot be secured merely through fear of punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies, and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.”

Those who fear their privacy is under threat, and who worry about other consequences of being tracked and traced, are unlikely to feel confident in a society that takes away basic freedoms during times of crisis and does not put dramatic changes into place via a parliamentary process. Governments should take note that this threatens pathways to safety.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on macho male leaders

Index on Censorship’s summer 2020 issue is entitled Private Lives: What happens when our every thought goes public

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2020 magazine podcast featuring the world premiere of a lockdown playlet written and acted out exclusively for Index on Censorship by Katherine Parkinson

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.