08 Apr 20 | Hungary, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Viktor Orbán Credit: European People’s Party/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán, leader of right-wing nationalist party Fidesz, has responded to the coronavirus crisis by pushing through sweeping emergency laws that have no time limit and have enormous potential to limit media freedom.

These laws essentially allow Orbán to rule by decree, which presents a huge threat to democracy and freedom of expression. While Index acknowledges that extraordinary measures need to be taken to protect lives, the passing of emergency laws of this nature for an indefinite time period was described in an Index statement as “an abuse of power”.

Under the emergency laws, journalists can be imprisoned for up to five years for publishing what the authorities consider to be falsehoods about the outbreak or measures taken to control it. But what exactly constitutes falsehoods is open to interpretation.

As Index notes, Hungary already has “one of the worst free speech records in Europe”. This further blow to journalists’ ability to report freely and objectively on the actions taken by the government is crippling for press freedom. It follows a pattern of state authorities infringing on press freedom under the guise of quashing “fake news” that Index has recorded happening globally in the wake of the crisis.

Transparency about the official numbers of those infected and those who have died from Covid-19 is critical for public safety. The scale of the outbreak will inform public behaviour and support for health services. Authoritarian regimes around the world such as North Korea and Turkmenistan have reported zero cases, the implausibility of which suggests censorship of the real figures by these countries’ despotic leaders.

Orbán is on the road to joining these leaders as, under the emergency laws, journalists are unable to hold the government to account over the accuracy of the data. Orbán has singular control of the public knowledge of the number of confirmed coronavirus cases, which, according to a government website, is 817 to date. See more here about this on the Index map tracking attacks on media freedom in Hungary.

Hungary’s neighbour Austria, which has a smaller population and recorded its first cases just 8 days before Hungary, has to date recorded 12,206 cases.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1586344862424-03642fb1-d46b-2″ taxonomies=”4157″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

08 Apr 20 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”113057″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Donald Trump tells a US reporter that her questioning is “horrid”, Jair Bolsonaro dismisses Covid-19 as a media conspiracy and the Spanish prime minister is petitioned by over 400 journalists to answer more questions. These incidents from leaders of the USA, Brazil and Spain are part of an emerging trend we are tracking on the Index on Censorship global map monitoring media freedom violations during the coronavirus pandemic. The map has been put together by our staff, our contributors and readers as well as our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation.

Several leaders around the globe are finessing the art of question evasion during this critical time, as highlighted by the map. In fact, some leaders have gone as far as supporting this kind of behaviour with legislation. Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro has issued a provisional measure which means that the government no longer has to answer freedom of information requests within the usual deadline. Marcelo Träsel of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism has called the measure “dangerous” as it gives scope for discretion in responding to requests.

The measure comes after weeks of Bolsonaro being questioned about his own health following a visit to the USA in which more than 20 people in his entourage tested positive for coronavirus after. When pressed on whether he too has it, he has made claims that he has had two negative tests, but refuses to show the results of either. To this day Brazilians don’t know whether he has the virus or not. Bolsonaro has also repeatedly dismissed coronavirus as “just a little flu”, “a bit of a cold” and as a media trick.

US President Trump has his own distraction technique when it comes to journalist questions – defensiveness and lashing out. Just this week, when asked about testing failures by Fox News reporter Kristen Fisher he responded: “You should say ‘congratulations, great job,’ instead of being so horrid in the way you ask a question.”

He’d employed similar words a few weeks earlier when NBC News journalist Peter Alexander asked: “What do you say to Americans, who are watching you right now, who are scared?”

“I say that you’re a terrible reporter. That’s what I say. I think it’s a very nasty question and I think it’s a very bad signal that you’re putting out to the American people,” he replied.

Another way of dodging the question is simply to deny coronavirus’ existence. Turkmenistan is excelling here. Reports have swirled around the internet that the word “coronavirus” is forbidden in Turkmenistan. Upon investigating, Index have not found sufficient evidence of this. What we have found evidence of though are credible reports that the virus is indeed in the country and has taken lives. A well-known writer from Turkmenistan has told Index that while the word coronavirus is not forbidden (and indeed is occasionally used by President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov himself on television), “the Turkmen government completely denies that coronavirus is present in the country”.

“At the same time, according to alternative information from the inside, in Turkmenistan, dozens of people die from the coronavirus daily since mid-March. However, everyone who dies of coronavirus gets another devised diagnosis, e.g. influenza, high blood pressure, food poisoning and so on,” he said.

This trend is deeply troubling. Knowing as much about a deadly, incredibly contagious virus that is spreading in your country is essential information. Journalists have every right to ask questions about it and should be receiving honest, accurate information in return. When these leaders withhold and barriers are put up, the situation is exacerbated and more people’s lives are put at risk.

Of course when it comes to some of the leaders and governments, their reluctance to engage with the media is nothing new. Bolsonaro has appeared on Facebook raging against journalists several times in the year he has been in power, while Trump has famously kicked media out of the room. But coronavirus has given a new lease of life to these tactics – with consequences that will become more devastating as the days pass.

Fortunately, there has been pushback. In Spain, politicians’ refusal to engage with media has led to an open letter being signed by over 400 Spanish journalists. They asked the government to revise the new policy which demands questions to be sent to the press secretary, who can chose to ask them, or not, thereby impacting journalists’ ability to hold power to account. And MEPs in Europe have said they will keep an eye on legislation that is being passed in EU member states in the name of coronavirus to ensure that it is proportionate, justified and doesn’t hamper human rights.

We hope these measures are effective at curtailing this trend. There is no good time to shut out and attack the media, not least during a global pandemic. In the meantime, we’ll continue to map.

If you know of any incidents of attacks against the media as a result of coronavirus, please report them to our map here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

06 Apr 20 | News and features, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Misinformation is everywhere and I don’t know who to trust, writes a Chinese writer, based in Nanjing” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_single_image image=”113000″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Wuhan doctor Li Wenliang told several of his friends in Chinese social media app WeChat to be careful because some patients had caught a SARS-like disease in his hospital. Within hours of this message being sent it had gone viral – without his name being removed. Li was then accused of rumour mongering. He was called to a local police station and reprimanded. But, not jailed, he returned to work, only to contract coronavirus himself. He died on 7 February.

In the wake of the outbreak of coronavirus, the internet police in China first tried to block information about the disease to maintain society order. This was what Li fell victim to. Then, as the situation became out of control, the main target of censorship moved to suppressing negative coverage, as China tried to position itself as a model country in the fight against coronavirus. There was no bad news, even though there was clearly bad news. Did people believe this positive coverage? It’s hard to tell. Looking at related topics on Sina Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, most comments have been complimentary. After the lockdown of Wuhan, the local medical system was overburdened. People who couldn’t get treatment asked for help on the internet, but the number of such messages fell from being in the thousands each day initially to hardly any later. Pictures of chaotic scenes in hospitals were removed.

The coronavirus is now storming throughout the world at an increasing speed and scale. It has greatly impeded global activities, as if a pause button on life has been pressed.

As the disease has spread around China, something else has been on the move – the intensification of censorship. While censorship existed before coronavirus, it has rapidly increased since then. And I fear this increase in censorship will not stop soon, even if the virus does.

During this time I have been in Nanjing, a former capital city near Shanghai. All I have been able to do is to watch official news and online discussions to see the latest development of the situation. But in China, where the news is tightly controlled, it’s really hard to identify the correct information. Misleading information is everywhere and you don’t know who to trust. I have felt helpless and the only thing I securely know I can do is to stay at home with family and pray for safety.

At the same time, there has been anger over the censoring of important information. In a recent interview published in the magazine Renwu, Ai Fen, head of the emergency department in a major hospital in Wuhan, recounted her experience. She told the magazine that she was the first to alert other people about the novel virus but was told by her hospital not to spread this information, not even to her husband. The article published on Renwu was quickly removed. And yet there have been many translated versions of the original, including in German, English, even Braille. We won’t let her testimony be deleted.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”She told the magazine that she was the first to alert other people about the novel virus but was told by her hospital not to spread this information, not even to her husband. The article published on Renwu was quickly removed.” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The impact of such severe censorship during this critical time has been catastrophic. The censorship carried out by the authorities during coronavirus is not vastly different to that that happens during other sensitive periods, such as around the Tiananmen Square anniversary, except that coronavirus is a global public health crisis, as pointed out by Lotus Ruan, a researcher from Citizen Lab. The censorship of neutral and even factual information related to the virus, which is completely unnecessary, might have limited the public’s ability to share and discuss critical knowledge of how to prevent the virus’ spread. For example, many elderly Chinese people refused to wear masks at the early stage of spread because the government claimed that the disease was preventable, containable and curable and there was no evidence that the virus was contagious between people. Even my grandparents thought I was making a big deal out of the virus.

There was a crucial time-lag of several weeks between when the first doctors started to notify people of the virus and when the authorities actually allowed it to be openly discussed and taken seriously.

China is now starting to come out of quarantine. And just in time for the traditional festival, Qingming, which was this weekend and commemorates the deceased. Residents in the city of Wuhan were allowed to take their departed family’s ashes from the funeral parlor. And yet we were all puzzled. Many web portals and social media platforms received orders not to report news about this, and there were security officers at sites to stop people taking photos. Such action has added more grief to this tragic scene. “The crowd were so quiet. No crying. No dirge. They just left with an urn in silence”, wrote someone on Weibo.

I am lucky. Nanjing has been a relatively safe place since the outbreak. Very few have been infected and as yet there have been no reported deaths. As for the residents of Wuhan, we can’t help but ask: have these people lost their right to mourn?

On 19 March, the official investigation on Li Wenliang’s death was released. It called for Li’s reprimand to be withdrawn and for two policemen who were involved in Li’s arrest to be warned as a punishment and response to the incident. Obviously, this is not enough in the view of the public. The true cause of Li’s tragedy is the deeply rooted censorship which has become a part of daily life. Anyone could be the next Li Wenliang.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The author of this piece is a freelance journalist based in Nanjing, China.

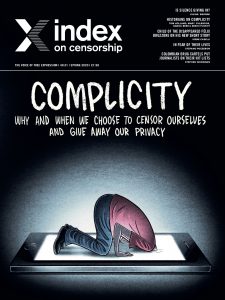

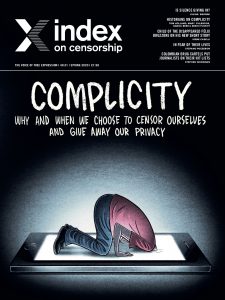

Index on Censorship’s spring 2020 issue is entitled Complicity: Why and when we chose to censor ourselves and give away our privacy

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

02 Apr 20 | News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

International Journalism Festival/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]“In the Middle Ages people watched convicts getting quartered in public squares. Nowadays, on social media, they watch reporters as they live-tweet their ordeals: detention, physical attacks on the streets, losing their livelihoods,” said Turkish author and journalist Kaya Genç.

“For most Turks, watching journalists getting sacked or imprisoned or destroying each other’s careers became entertainment.”

Genç spoke to Index to answer questions posed by the Index youth advisory board about life as a journalist in Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and his latest book, The Lion and the Nightingale: A Journey Through Modern Turkey.

The youth board are elected for six months, and meet once a month online over that period to discuss freedom of expression issues. They are based around the world.

Hana Meihan Davis, from Hong Kong, asked how Erdogan managed to strip Turkey of journalistic freedom. Genç explained that divisions have existed between political sects in the media for decades, which the current ruling party was then able to take advantage of.

“When Islamists were in trouble in the 1990s secularists supported court cases against them; when secularists were locked up some liberals applauded; when Kurds were imprisoned most journalists looked the other way. Now as most of their colleagues are sacked or locked up conservatives act as if all is normal,” said Genç, who is also a contributing editor to Index on Censorship magazine.

Amid this sense of apathy Erdogan moved to create “a small army of loyalists in the media” as other news sites and newspapers were closed down.

Davis followed up her question, asking if people realised what was happening at the time? This is a question often asked when we look back with hindsight at the gradual erosion of freedoms. Were people like a frog who doesn’t realise the temperature of his water is slowly being increased to boiling? Genç said some journalists saw the dangers.

“Reporters and editors declared their independence, or found new patrons, and they are producing excellent work away from the influence of state power. I’m sure they were aware of what was happening while they worked at titles now tamed and indirectly owned by the government.”

The landscape for journalists in Turkey today is rocky terrain. There is an acute awareness of the censorship laws that can be imposed, coupled with a determination to provide much needed accurate reporting.

From the UK, Saffiyah Khalique asked about the laws around “public sensitivities”, which can result in imprisonment for up to a year for disrespecting the beliefs of religious groups, insulting Turkishness and other such “offences”. Genç said they are used within society to silence political dissenters.

“Twitter trolls who present themselves as pro-government journalists use these unclear laws to put their enemies behind bars. If an artist, piano player or actor says something critical about the government, they go through their timeline, find something they find insulting, and ask the public prosecutor to step in.”

Despite this possibility of prosecution being ever around the corner, Genç said he does not feel unsafe or threatened as a journalist in Turkey. “I feel free”, he answered to a question from Emily Boyle, a dual citizen of the UK and Switzerland

Recognising the value of objectivity appears to be Genç’s lifeline. When Indian national Samarth Mishra asked what is the most difficult part of being a journalist in Turkey, Genç said: “The hardest thing for a writer reporting from Turkey is to remain objective. You can’t be bitter about the government. Readers can benefit from the cold heart of a writer who does her best to be objective in her reporting.”

He said: “Our job, as writers, is to hold people with power to account, not to promote this or that political leader, defend this or that political ideology, propagate for this or that country … When a writer inhibits a space where nobody can accuse her of partisanship, believe me the effect of her writing will be much greater.”

The Lion and the Nightingale, Genç’s latest book, was published recently. It takes the reader on a journey through modern Turkey while exploring its history, via interviews he conducted on the road. Egil Sturk, from Sweden, asked Genç if there were any questions he was hesitant to ask his interviewees.

Genç said: “I am hesitant to ask questions about people’s religious beliefs and fiery ideological commitments. I prefer to give them enough space to articulate themselves where the bizarre, the eerie appears like a diamond in a mine. When people feel safe they tell you the most amazing things. Like an analyst you need to just sit there and listen.”

In answer to a question from Aliyah Orr (UK) about the emotional impact of the interviews he was conducting, Genç said:

“The prison chronicle of my friend and colleague Murat Çelikkan … had the strongest emotional effect on me. We used to work together, behind adjacent desks, and his experience in prison was empowering and unsettling. His account of imprisonment was rich with detail and you could see a great writer disappearing into the story’s characters and particulars of his story.”

Faye Gear from Canada asked what is different about today’s landscape in terms of freedom of expression. To tackle the suppression of free speech, Genç said people must think for themselves.

“I grew up idolising individual thinkers and writers: Susan Sontag, Jacques Derrida, Chantal Mouffe, VS Naipaul,” said Genç. “Nowadays we are invited to subscribe to what seems to be the most forward-thinking tribe and then follow its leaders by liking and retweeting their political snippets.”

In the face of an atmosphere of censorship, Genç remains defiant. In answer to a question from Satyabhama Rajoria, from India, about the struggles he faces as a journalist and author, Genç said: “There is of course always the anxiety that comes with publishing your writing, but that is healthy. Bullies, from the left and the right, may take your sentences out of context but that, too, is something one can deal with.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”112300″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1585828417099-e398f95f-d0bf-6″ taxonomies=”7355″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

02 Apr 20 | News and features, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is among 107 organisations that are urging governments to respect human rights and civil liberties as they attempt to tackle the coronavirus pandemic through digital surveillance technologies.

“As the coronavirus continues to spread and threaten public health, governments are taking unprecedented actions to bring it under control. But the pandemic must not be used to usher in invasive digital surveillance,” said Jessica Ní Mhainín, Policy Research and Advocacy Officer at Index on Censorship. “Measures must have a legal basis, be targeted exclusively at curtailing the virus, and have safeguards in place to prevent violations of privacy.”

STATEMENT:

The Covid-19 pandemic is a global public health emergency that requires a coordinated and large-scale response by governments worldwide. However, states’ efforts to contain the virus must not be used as a cover to usher in a new era of greatly expanded systems of invasive digital surveillance.

We, the undersigned organisations, urge governments to show leadership in tackling the pandemic in a way that ensures that the use of digital technologies to track and monitor individuals and populations is carried out strictly in line with human rights.

Technology can and should play an important role during this effort to save lives, such as to spread public health messages and increase access to health care. However, an increase in state digital surveillance powers, such as obtaining access to mobile phone location data, threatens privacy, freedom of expression and freedom of association, in ways that could violate rights and degrade trust in public authorities – undermining the effectiveness of any public health response. Such measures also pose a risk of discrimination and may disproportionately harm already marginalised communities.

These are extraordinary times, but human rights law still applies. Indeed, the human rights framework is designed to ensure that different rights can be carefully balanced to protect individuals and wider societies. States cannot simply disregard rights such as privacy and freedom of expression in the name of tackling a public health crisis. On the contrary, protecting human rights also promotes public health. Now more than ever, governments must rigorously ensure that any restrictions to these rights is in line with long-established human rights safeguards.

This crisis offers an opportunity to demonstrate our shared humanity. We can make extraordinary efforts to fight this pandemic that are consistent with human rights standards and the rule of law. The decisions that governments make now to confront the pandemic will shape what the world looks like in the future.

We call on all governments not to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic with increased digital surveillance unless the following conditions are met:

1. Surveillance measures adopted to address the pandemic must be lawful, necessary and proportionate. They must be provided for by law and must be justified by legitimate public health objectives, as determined by the appropriate public health authorities, and be proportionate to those needs. Governments must be transparent about the measures they are taking so that they can be scrutinized and if appropriate later modified, retracted, or overturned. We cannot allow the Covid-19 pandemic to serve as an excuse for indiscriminate mass surveillance.

2. If governments expand monitoring and surveillance powers then such powers must be time-bound, and only continue for as long as necessary to address the current pandemic. We cannot allow the Covid-19 pandemic to serve as an excuse for indefinite surveillance.

3. States must ensure that increased collection, retention, and aggregation of personal data, including health data, is only used for the purposes of responding to the Covid-19 pandemic. Data collected, retained, and aggregated to respond to the pandemic must be limited in scope, time-bound in relation to the pandemic and must not be used for commercial or any other purposes. We cannot allow the Covid-19 pandemic to serve as an excuse to gut individuals’ right to privacy.

4. Governments must take every effort to protect people’s data, including ensuring sufficient security of any personal data collected and of any devices, applications, networks, or services involved in collection, transmission, processing, and storage. Any claims that data is anonymous must be based on evidence and supported with sufficient information regarding how it has been anonymised. We cannot allow attempts to respond to this pandemic to be used as justification for compromising people’s digital safety.

5. Any use of digital surveillance technologies in responding to Covid-19, including big data and artificial intelligence systems, must address the risk that these tools will facilitate discrimination and other rights abuses against racial minorities, people living in poverty, and other marginalised populations, whose needs and lived realities may be obscured or misrepresented in large datasets. We cannot allow the Covid-19 pandemic to further increase the gap in the enjoyment of human rights between different groups in society.

6. If governments enter into data sharing agreements with other public or private sector entities, they must be based on law, and the existence of these agreements and information necessary to assess their impact on privacy and human rights must be publicly disclosed – in writing, with sunset clauses, public oversight and other safeguards by default. Businesses involved in efforts by governments to tackle Covid-19 must undertake due diligence to ensure they respect human rights, and ensure any intervention is firewalled from other business and commercial interests. We cannot allow the Covid-19 pandemic to serve as an excuse for keeping people in the dark about what information their governments are gathering and sharing with third parties.

7. Any response must incorporate accountability protections and safeguards against abuse. Increased surveillance efforts related to Covid-19 should not fall under the domain of security or intelligence agencies and must be subject to effective oversight by appropriate independent bodies. Further, individuals must be given the opportunity to know about and challenge any Covid-19 related measures to collect, aggregate, and retain, and use data. Individuals who have been subjected to surveillance must have access to effective remedies.

8. Covid-19 related responses that include data collection efforts should include means for free, active, and meaningful participation of relevant stakeholders, in particular experts in the public health sector and the most marginalized population groups.

Signatories:

7amleh – Arab Center for Social Media Advancement

Access Now

African Declaration on Internet Rights and Freedoms Coalition

AI Now

Algorithm Watch

Alternatif Bilisim

Amnesty International

ApTI

ARTICLE 19

Asociación para una Ciudadanía Participativa, ACI Participa

Association for Progressive Communications (APC)

ASUTIC, Senegal

Athan – Freedom of Expression Activist Organization

Barracón Digital

Big Brother Watch

Bits of Freedom

Center for Advancement of Rights and Democracy (CARD)

Center for Digital Democracy

Center for Economic Justice

Centro De Estudios Constitucionales y de Derechos Humanos de Rosario

Chaos Computer Club – CCC

Citizen D / Državljan D

Civil Liberties Union for Europe

CódigoSur

Coding Rights

Coletivo Brasil de Comunicação Social

Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA)

Comité por la Libre Expresión (C-Libre)

Committee to Protect Journalists

Consumer Action

Consumer Federation of America

Cooperativa Tierra Común

Creative Commons Uruguay

D3 – Defesa dos Direitos Digitais

Data Privacy Brasil

Democratic Transition and Human Rights Support Center “DAAM”

Derechos Digitales

Digital Rights Lawyers Initiative (DRLI)

Digital Security Lab Ukraine

Digitalcourage

EPIC

epicenter.works

European Digital Rights – EDRi

Fitug

Foundation for Information Policy Research

Foundation for Media Alternatives

Fundación Acceso (Centroamérica)

Fundación Ciudadanía y Desarrollo, Ecuador

Fundación Datos Protegidos

Fundación Internet Bolivia

Fundación Taigüey, República Dominicana

Fundación Vía Libre

Hermes Center

Hiperderecho

Homo Digitalis

Human Rights Watch

Hungarian Civil Liberties Union

ImpACT International for Human Rights Policies

Index on Censorship

Initiative für Netzfreiheit

Innovation for Change – Middle East and North Africa

International Commission of Jurists

International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

Intervozes – Coletivo Brasil de Comunicação Social

Ipandetec

IPPF

Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL)

IT-Political Association of Denmark

Iuridicum Remedium z.s. (IURE)

Karisma

La Quadrature du Net

Liberia Information Technology Student Union

Liberty

Luchadoras

Majal.org

Masaar “Community for Technology and Law”

Media Rights Agenda (Nigeria)

MENA Rights Group

Metamorphosis Foundation

New America’s Open Technology Institute

Observacom

Open Data Institute

Open Rights Group

OpenMedia

OutRight Action International

Pangea

Panoptykon Foundation

Paradigm Initiative (PIN)

PEN International

Privacy International

Public Citizen

Public Knowledge

R3D: Red en Defensa de los Derechos Digitales

RedesAyuda

SHARE Foundation

Skyline International for Human Rights

Sursiendo

Swedish Consumers’ Association

Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP)

Tech Inquiry

TechHerNG

TEDIC

The Bachchao Project

Unwanted Witness, Uganda

WITNESS

World Wide Web Foundation

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

31 Mar 20 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”60471″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]As coronavirus spreads across Europe so too do issues surrounding the transparency and accuracy of information on it. This is deeply troubling given the importance of reliable information about the pandemic. So what exactly are the main roadblocks to accurate facts? Here are the key trends when it comes to coronavirus and free expression in Europe.

Scapegoating

Scapegoating, an unhelpful habit historically used by Russian propagandists to foist blame onto their Cold War opponents, is now being used to suggest that coronavirus may have been brewed in a lab by the Americans in order to cripple the Chinese economy. This is one of many bizarre theories that were spread among the Russian population in a bid to confuse and distract.

Another form of scapegoating has reared its head in France, in particular, in the form of racism against people with Asian heritage. There have been reports of French-Asians suffering racist abuse on the streets, public transport and in school. This has also been an issue in the USA, where President Donald Trump angered Chinese authorities by referring to coronavirus as the “Chinese Virus”.

Criminalisation of “fake news”

In the USA, the term “fake news” can easily be used to discredit accurate reporting that Trump doesn’t like, which is why the criminalisation of news designated as “fake” by world leaders generally is so dangerous. Hungary’s parliament has passed a law to let Prime Minister Viktor Orban rule by decree for an indefinite period of time, and the state has the power to imprison people considered to have spread false information – aka “fake news” – about coronavirus.

This trend is present elsewhere in Europe as governments attempt to control information on coronavirus. Patrick Sensburg, a member of the ruling party in Germany, said in an interview that the government should consider “ratcheting up statutory offenses” to penalise those spreading news considered fake by the state.

Republika Srpska, one of the two entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, has also introduced fines for publishing false news and allegations that “cause panic and fear among citizens” in the mainstream press and social media.

Opaque about the figures

While high numbers of recorded cases and deaths from coronavirus are something every country would rather avoid, transparency is key to members of the public being fully informed and understanding the risks. According to the Financial Times, Kim Jong Un has publicly denied any cases in North Korea while at the same time quietly soliciting aid from abroad. In Europe, Turkey has displayed signs of being unwilling to disclose accurate figures. On 23 March, after data showed fewer and fewer people were being tested over successive days, possibly to reduce the number of cases on record, the Turkish Medical Association urged the Turkish government to test more people. They believe the government figures may be propaganda, designed to flatter the state’s control of the situation, which a doctor, speaking anonymously, claimed was in fact “out of control”.

Ill-informed leaders

At a time of a global pandemic, world leaders would serve their citizens best by bowing to the greater wisdom of medical experts. Unfortunately, some European leaders have appointed themselves as “experts” in the field of cures for coronavirus, an unfortunate echo of leaders who made false claims about cures for Aids when it swept through Africa. Speaking on state television for instance, President Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus claimed that people in the countryside should continue working: “The tractor will heal everyone. The fields heal everyone”. Serbia’s president, Aleksandar Vucic, said he had found a reason to have an extra drink every day, after he claimed health specialists had told him that coronavirus “doesn’t grow wherever you put alcohol”. Please note: there is no scientific evidence to suggest that drinking alcohol has any effect on coronavirus.

We have previously reported on how censorship in China was impacting the way news about coronavirus was being reported, and vital information being distributed. We are also mapping all of the attacks on the media right now, which are growing sharply by the day. This represents one of the most worrying attacks on free speech in Europe right now.

The incidents on the map are collated by our staff, contributors and readers as well as our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation and verified by our team before pubication. Please check out the map here and do notify us via the map of any attacks we might have missed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Mar 20 | Magazine, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Ak Welsapar, Julian Baggini, Alison Flood, Jean-Paul Marthoz and Victoria Pavlova”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

In our In Focus section, we sit down with different generations of people from Turkey and China and discuss with them what they can and cannot talk about today compared to the past. We also look at how as world demand for cocaine grows, journalists in Colombia are increasingly under threat. Finally, is internet browsing biased against LBGTQ stories? A special Index investigation.

Our culture section contains an exclusive short story from Libyan writer Najwa Bin Shatwan about an author changing her story to people please, as well as stories from Argentina and Bangladesh.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Willingly watched by Noelle Mateer: Chinese people are installing their own video cameras as they believe losing privacy is a price they are willing to pay for enhanced safety

The big deal by Jean-Paul Marthoz: French journalists past and present have felt pressure to conform to the view of the tribe in their reporting

Don’t let them call the tune by Jeffrey Wasserstrom: A professor debates the moral questions about speaking at events sponsored by an organisation with links to the Chinese government

Chipping away at our privacy by Nathalie Rothschild: Swedes are having microchips inserted under their skin. What does that mean for their privacy?

There’s nothing wrong with being scared by Kirsten Han: As a journalist from Singapore grows up, her views on those who have self-censored change

How to ruin a good dinner party by Jemimah Steinfeld: We’re told not to discuss sex, politics and religion at the dinner table, but what happens to our free speech when we give in to that rule?

Sshh… No speaking out by Alison Flood: Historians Tom Holland, Mary Fulbrook, Serhii Plokhy and Daniel Beer discuss the people from the past who were guilty of complicity

Making foes out of friends by Steven Borowiec: North Korea’s grave human rights record is off the negotiation table in talks with South Korea. Why?

Nothing in life is free by Mark Frary: An investigation into how much information and privacy we are giving away on our phones

Not my turf by Jemimah Steinfeld: Helen Lewis argues that vitriol around the trans debate means only extreme voices are being heard

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: You’ve just signed away your freedom to dream in private

Driven towards the exit by Victoria Pavlova: As Bulgarian media is bought up by those with ties to the government, journalists are being forced out of the industry

Shadowing the golden age of Soviet censorship by Ak Welsapar: The Turkmen author discusses those who got in bed with the old regime, and what’s happening now

Silent majority by Stefano Pozzebon: A culture of fear has taken over Venezuela, where people are facing prison for being critical

Academically challenged by Kaya Genç: A Turkish academic who worried about publicly criticising the government hit a tipping point once her name was faked on a petition

Unhealthy market by Charlotte Middlehurst: As coronavirus affects China’s economy, will a weaker market mean international companies have more power to stand up for freedom of expression?

When silence is not enough by Julian Baggini: The philosopher ponders the dilemma of when you have to speak out and when it is OK not to[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Generations apart by Kaya Genç and Karoline Kan: We sat down with Turkish and Chinese families to hear whether things really are that different between the generations when it comes to free speech

Crossing the line by Stephen Woodman: Cartels trading in cocaine are taking violent action to stop journalists reporting on them

A slap in the face by Alessio Perrone: Meet the Italian journalist who has had to fight over 126 lawsuits all aimed at silencing her

Con (census) by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Turns out national censuses are controversial, especially in the countries where information is most tightly controlled

The documentary Bolsonaro doesn’t want made by Rachael Jolley: Brazil’s president has pulled the plug on funding for the TV series Transversais. Why? We speak to the director and publish extracts from its pitch

Queer erasure by Andy Lee Roth and April Anderson: Internet browsing can be biased against LGBTQ people, new exclusive research shows[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Up in smoke by Félix Bruzzone: A semi-autobiographical story from the son of two of Argentina’s disappeared

Between the gavel and the anvil by Najwa Bin Shatwan: A new short story about a Libyan author who starts changing her story to please neighbours

We could all disappear by Neamat Imam: The Bangladesh novelist on why his next book is about a famous writer who disappeared in the 1970s[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]Demand points of view by Orna Herr: A new Index initiative has allowed people to debate about all of the issues we’re otherwise avoiding[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Ticking the boxes by Jemimah Steinfeld: Voter turnout has never felt more important and has led to many new organisations setting out to encourage this. But they face many obstacles[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Mar 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”112844″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]When the political scientist and historian Benedict Anderson wrote about nations in his 1983 book Imagined Communities, he said that belonging to them was particularly felt at certain moments. Reading the daily newspaper for one; watching those 11 men representing your country on the football field another. If Anderson were alive today, he might add “getting a government text message” to the list. Last Tuesday people throughout the UK all shared in this experience. Following Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s announcement the night before that we must all stay in, with few exceptions, the nation’s phones pinged to the alert “New rules in force now: you must stay at home. More info and exemptions at gov.uk/coronavirus Stay at home. Protect the NHS. Save lives.” It was a first. The government had never before used the UK’s mobile networks to send out a message on mass.

By “force” the message meant exactly that. Police now have the power to fine those who flout the new rules. Quickly videos have emerged of officers approaching people on the streets, such as one showing sunbathers in Shepherd’s Bush being told to leave, and photos of a 25-person strong karaoke party that was dispersed this weekend. Almost overnight we went from being a nation where most people could come and go as they pleased to one in which we can barely leave our front door.

State-of-emergency measures are necessary in a real crisis, which is where we land today. Hospital beds are filling up fast, the death toll is rising, the threat of contagion is real and high. Few would argue that something drastic didn’t need to be done. But that does not mean we should blindly accept all that is happening in the name of our health. Proportionality – whether the measures are a justified or over-reaching response to the current danger – and implication – how they could be used in other aspects – are questions we should and must ask.

The new rules of UK life have been enshrined in the Coronavirus Bill. The bill, a complex and lengthy affair, gives the government a lot of power. Take for example the rules that allow authorities to isolate or detain individuals who are judged to be a risk to containing the spread of Covid-19. What exactly does a risk mean? Would it be the journalist Kaka Touda Mamane Goni from Niger, who last week was arrested because he spoke of a hospital that had a coronavirus case and was quickly branded a threat to public order? Or how about Blaž Zgaga, a Slovenian journalist who contacted Index several weeks back to say he had been added to a list of those who have the disease (something he denies) and must be detained? This followed him calling up the government on their own coronavirus tactics. He’s currently terrified for his life.

It’s easy to dismiss these examples as ones that are happening elsewhere and not here, until one day we wake up and that’s no longer the case.

And while many of us might be far away from authoritarian nations like China, whose government is tracking people’s movements through a combination of monitoring people’s smartphones, utilising now ubiquitous video surveillance and insisting people report their current medical condition, it might only be a matter of time before we catch up.

Singapore, another country with a state that has a tight grip on its population, has already offered to make the app they’re currently using to track exposure to the virus available to developers worldwide. The offer is free but at what other costs? The Singaporean government has been working hard to allay privacy concerns and yet some linger. Will people invite this new technology in their lives? Amid the panic that coronavirus has created, it’s not hard to imagine a scenario in which such tools are imported, embraced and normalised. As Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harrari writes in the FT:

“A big battle has been raging in recent years over our privacy. The coronavirus crisis could be the battle’s tipping point. For when people are given a choice between privacy and health, they will usually choose health.”

The coronavirus bill was meant to come with an expiry date, a “sunset clause” of two years, at which stage all former laws fall back into place. The sunset clause has since been removed, and instead in its place is a clause stating the legislation will be reviewed every six months. Politicians have also sought assurances that the measures will only apply to fighting the virus, to which they have been told yes they will only be used “when strictly necessary” and will remain in force only for as long as required. All positive and stuff we should welcome. And yet how often do politicians say one thing and do another? We must be watchful and hold them to their word.

This is particularly important with the clause that enables authorities to close down, cancel or restrict an event or venue if it poses a threat to public health, a clause that has bad implications for the ability to protest. Of course in the digital age there are many ways beyond going out on to the streets to make your voice heard. And even without the internet, we’ve seen several creative forms of protest from inside the home, such as the Brazilians who have shouted “get out” and bashed kitchenware at the window as a way to voice anger at President Jair Bolsonaro.

Marching on the streets in huge numbers is, however, amongst the most effective, hence its endurance. If in six months’ time the virus is under control and social distancing is no longer essential, this clause should at point-of-review be removed. And if it isn’t, we need to fight really hard until it is. Protest is one of the key foundations of a robust civil society. It’s not a right we want to see disappear.

The great British philosopher John Stuart Mill argued in On Liberty that “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

The coronavirus crisis passes Mill’s liberty test. It is causing harm to a great number of people. It’s therefore important to take it seriously and to provide the state with adequate powers to fight the pandemic, even if that means losing some of our freedoms in the here and now. At the same time we must make sure politicians do not use this moment to tighten their grip in ways that, as stated, are disproportionate and easily manipulated. And once this is all over we expect the bill to expire too, and any apps that might no longer be necessary. Our freedoms, so hard fought for, can be easily squandered. Let’s not lose liberties on top of lives.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Mar 20 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”112806″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Journalists beaten by batons in India; Brazil’s president lashing out at the media; a reporter arrested in Niger, all three stories tied together by a common thread – they dared to report on the coronavirus crisis.

As the world’s attention turns to fighting the pandemic, many of the world’s leaders want to fight the media at the same time. If anything, they’re taking this opportunity with the world being distracted to ramp up efforts to silence journalists.

This is why Index has launched a map in which we document what is going on around the world. The map is a partnership with Justice for Journalists Foundation who, together with our expertise running other mapping projects, will contribute by expanding cooperation with their existing regional partners in central Asia.

While we are aware some restrictions to movement and assembly are necessary at present and that these will invariably effect how journalists to do their jobs, we expect all restrictions to be lifted once the epidemic is under control, and are tracking those restrictions and attacks to media that go far beyond what could be considered reasonable and justified.

Already the response has been incredible, though deeply unsettling too. We’ve had alerts from across the globe, from the USA through to Brazil, from countries with poor records on freedom of expression to ones with higher standards. In one day alone we mapped nine new incidents. Nine. A sad reality of the world we live in today is that media violations are far from rare, but nine in a day is pretty astonishing.

At present China leads in terms of media attacks, which isn’t surprising given the duel facts of it being the country of coronavirus origin and one of the most censored media environments in the world. China’s bid to control news of the outbreak has seen a ramping up of media censorship, as Index reported at the time. Perhaps the most troubling of all stories to emerge was last month when three Wall Street Journal reporters were kicked out of the country following the newspaper publishing an opinion piece in which China was referred to as the sick man of Asia. Foreign media presence has been drained further since then. Last week China expelled more than 13 journalists from the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post and the New York Times and banned them from working in Hong Kong and Macau too.

If that wasn’t bad enough the Chinese government is expecting other countries to sing to their tune. When Dutch cartoonist Maarten Wolterink posted a cartoon showing a Chinese plane with a coronavirus clinging to its tailplane on 24 January, the Chinese ambassador in The Netherlands voiced his disapproval and an expectation that Dutch cartoonists would be censured if they “insulted” China. Similarly, in Denmark on 27 January a cartoon by Niels Bo Bojesen appeared in Jyllands-Posten that portrayed coronavirus particles taking the place of the stars on China’s national flag. The Chinese embassy in Copenhagen demanded a public apology. Fortunately, Danish politicians didn’t capitulate. They were vocal in their defence of the paper and the general principle of free expression.

But it’s not just China that is censoring information on the outbreak and kicking journalists out. Just yesterday news emerged that Egyptian authorities have forced Guardian journalist and former Index employee Ruth Michaelson to leave the country after she reported on a scientific study saying Egypt likely has more coronavirus cases than the official numbers. Michaelson, who has lived in and reported from Egypt since 2014, has now come to the end of the road for reporting in the country, all because of something she wrote about coronavirus.

Perhaps most alarming are the violations happening in countries that until now we have regarded as relatively free. In South Africa, for example, the government has stopped epidemiologists, virologists, infectious disease specialists and other experts from commenting on Covid-19. All requests for comment must be directed to the National Institute for Communicable Diseases. At a time when knowledge is crucial, when the internet is being flooded with disinformation, blocking access to those who are experts in the field is dangerous to say the least.

Similarly, in Slovenia the investigative journalist Blaž Zgaga has been subject to death threats and a smear campaign since submitting a request for information to the government about its management of the coronavirus crisis. Zgaga is now living in a state of fear. This in a country that ranked 34 out of 180 countries in the RSF world press freedom index 2019. Is Slovenia about to turn its back on media freedom?

All of these examples show why the map is critical. We need to let it be known to people and politicians that we are watching and that we are documenting. We need to increase awareness around the world about the current state of press freedom during the coronavirus crisis, as well as to raise awareness more broadly about the importance of media freedom and the challenges that journalists face. We need to rally behind and help journalists as much as we can during this incredibly difficult period. And, moving forward, we need to improve media freedom globally. After all, the tools used against journalists right now didn’t just emerge overnight – they’ve been finessed, tailored and expanded over the years.

These are unprecedented times and in moments of crisis our freedoms have a tendency to slide away from us. But these are also times when good, honest, trusty-worthy journalism is more important than ever. We intend to hold those in power to account and to aid those at the forefront of reporting on the coronavirus crisis.

For more information on the map and/or to report an attack, please click here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Mar 20 | News and features, Press Releases, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship and Justice for Journalists Foundation (JFJ) announce a joint global initiative to monitor attacks and violations against the media, specific to the current coronavirus-related crisis.

According to Rachael Jolley, Editor-in-Chief, Index of Censorship: “In times of extraordinary crisis, governments often take the opportunity to roll back on personal freedoms and media freedom. The public’s right to know can be severely reduced with the little democratic process. Index is already being alerted to attacks and violations against the media in the current coronavirus related crisis, as well as other alarming news pertaining to privacy and freedoms”.

“In our daily work in the post-Soviet region, Justice for Journalists Foundation experts and partners come across grave violations of media freedom and media workers’ human rights. Today, we are witnessing how the corrupt governments and businessmen in many of the regional autocracies are abusing the current limitations of public scrutiny. This major decrease in civil liberties makes pursuing their interests easier and even less transparent, whereas media workers striving to unveil murky practices are facing more risks than ever before”, said Maria Ordzhonikidze, JFJ’s Director.

Index draws on its experience running other mapping projects to enable easy comparisons of media violations in each country, and also so data can be collated and discussed when the global crisis is over.

Justice for Journalists Foundation will contribute to this monitoring effort by expanding cooperation with its existing regional partners who provide data and analysis for the series of Media Threats and Attacks Reports in Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

The overall goal of the project is threefold: to increase awareness about the importance of media freedom and the existing state of press freedom at this particular point in history, to support journalists whose work is being impeded, by highlighting the challenges they face to an international audience and to continue to improve media freedom globally in the long run.

Anyone interested to learn more about or contribute to this initiative by providing information on incidents and/or translation, publicity and ideas, please get in touch:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Mar 20 | Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Media freedom is more essential than ever during the current coronavirus pandemic. An independent media is a trustworthy source of information at a time when misinformation and disinformation is rife and a way to hold those in power to account. Nonetheless journalists are being threatened, attacked and censored in the name of the pandemic.

Index on Censorship, alongside eight other media freedom organisations, is calling on European leaders to protect the free flow of information and to ensure that governments do not take advantage of the pandemic to suppress the media.

Please see our joint statement below:

Ursula Von der Leyen, President of the European Commission

Charles Michel, President of the European Council and David Sassoli

President of the European Parliament

25 March 2020

Re: Call for Europe’s leaders to protect free flow of information to tackle COVID-19

Dear Presidents of the European Commission, the European Council and the European Parliament,

We, the undersigned press freedom and freedom of expression organisations, are writing to express our profound concerns about the dangers of governments taking advantage of the Covid-19 pandemic to punish independent and critical media and to introduce restrictions on the access of media to government decision making and action.

The free flow of independent news is more essential than ever, both for informing the public on vital measures to contain the virus as well as in maintaining public scrutiny and debate on the adequacy of those measures.

In this respect we support the joint statement put out by the three global and regional special rapporteurs for freedom of expression, David Kaye (U.N.), Harlem Désir (OSCE) and Edison Lanza (OAS), that the “right to freedom of expression, ……, applies to everyone, everywhere, and may only be subject to narrow restrictions”.

While we appreciate that certain emergency measures are needed to combat the pandemic, all such measures must be necessary, proportionate, temporary, strictly time-limited and subject to regular scrutiny, in order to solve the immediate health crisis. Unfortunately, numerous governments around the world are already using the pandemic to claim excessive powers that can undermine democratic institutions, including the free press. These dangerous developments could easily outlive the current health crisis unless we act urgently to stop them.

This week, the Hungarian government is demanding an indefinite extension of the state of emergency and the power to impose prison sentences of up to five years on journalists and others for promoting false information related to COVID-19.

Our organizations are acutely aware of the dangers of disinformation and how it is used by unscrupulous groups to spread panic and division. However, this does not justify draconian powers that risk being used against journalists whose work is indispensable in protecting public health and ensuring accountability.

It is little surprise that Hungary, with its record of undermining media freedom, should be the first EU member state to make such an extreme and opportunistic power grab. The few remaining independent media outlets in the country are regularly attacked and accused of spreading “fake news” for raising simple questions about the government’s preparedness and strategy for tackling the pandemic. If approved, this new law would grant the Hungarian government a convenient tool to threaten journalists and intimidate them into self-censorship. We fear this is a step toward the complete repression of media freedom in Hungary that could outlive the pandemic.

Were this law to pass it would set a fearful precedent for other European Union member states tempted to follow Hungary’s example – troubling signs exist in other states as well – and do untold damage to fundamental rights and democracy as well as undermining efforts to end the pandemic.

Secondly, our organizations are also concerned about the proliferation of enhanced surveillance measures introduced to monitor the spread of the virus. While we understand the potential benefits, the use of surveillance must have proper oversight and be clearly limited to tackling the pandemic. Unchecked surveillance endangers privacy and data rights, while journalists’ ability to protect sources is undermined and self-censorship rises.

Thirdly, our organizations are concerned about media access to government officials, decision makers, medical experts and those on the front line of the pandemic. Many countries have introduced restrictions on freedom of movement which we insist must not be used to prevent media from bearing witness to the crisis.

At the same time many governments are restricting access to officials by reducing the physical presence of journalists to press conferences. Slovenia and the Czech Republic for example announced ending them altogether. Such measures must not be allowed to restrict media scrutiny of government.

We are in the early stages of the pandemic where, for the most part, governments and media are cooperating closely as they struggle to respond to this unprecedented threat to public health. They both have a duty to ensure the public are fully informed and the response to the pandemic is as effective as possible.

However, we are acutely aware that as the crisis persists, the death toll mounts and as widespread job losses and a certain global recession loom, the actions and decisions of government will come under intense examination. The temptation for some governments to abuse new found emergency powers to stifle criticism will, in some cases, be overwhelming. This must not be allowed to happen.

In a period when our citizens’ fundamental rights are being suspended around Europe, the need for media scrutiny to ensure no abuse of these new powers are stronger than ever.

We therefore call on you to use the power of your offices to ensure that fundamental human rights and press freedom will be guaranteed as the European Union strives to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic.

In particular we ask you to

- Robustly oppose the measures currently before the Hungarian parliament and make it clear that the European Union will not accept the application of Emergency legislation that undermines fundamental human rights and media freedoms

- Demand that governments ensure full access for media professionals to decision makers and actors on the front line of the health crisis as well as the broader workings of government,

- Declare journalism and the free flow of information as essential to Europe’s efforts to contain the COVID-19 pandemic

Kind Regards,

ARTICLE 19

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

European Federation of Journalists

Free Press Unlimited (FPU)

Index on Censorship

International Federation of Journalists

International Press Institute (IPI)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Index on Censorship has created a monitoring map to track media violations during the coronavirus crisis. If you know of an attack on media freedom during this crisis, please use this form to report it.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Mar 20 | News and features, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Spanish journalist Silvia Nortes reports on the trend amongst Spanish journalists of self-censoring in the face of job losses and a divided society, a special piece as part of the 2020 spring edition of Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_single_image image=”112712″ img_size=”large” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Paulino Ros, a journalist with 35 years’ experience in radio, admits he self-censors. It’s understandable – after all, he lost a job because of his reporting of a corruption case.

“The case was confirmed two months later and charges were laid by the Court of Instruction and the police made arrests. Even so, my crime of publishing ended up costing me my job and, even worse, my health,” he said. Ros censors himself “almost every day, so as not to displease my superiors. I stick to the editorial line”.

He is not alone. The co-founder of major Spanish newspaper El País, Juan Luis Cebrián, said recently that plenty of journalists were tailoring what they wrote or said because there was “no free debate, because people think it is better not to mess with that because of social rejection”.

Unlike Ros, most are reluctant to admit to this on record, but the idea that self-censorship is rife is backed up by statistics. The 2016 Annual Report of Journalism by the Madrid Press Association recorded alarming data, for example: 75% of journalists yield to pressure, and more than half acknowledge they usually censor themselves.

And it’s getting worse as certain issues within society are becoming more divisive. In Spain, social movements are strong engines of heated debates. The controversy they generate can pose a danger to journalistic independence, due to the temptation to follow a majority view.

The tension is obvious when reporting on Catalonia, where the resurgence of the independence movement has given rise to a silencing form of nationalism. Journalists working in Catalonia for national media, such as television channels Antena 3 and La Sexta, are branded as “manipulators” by pro-independence social movements. Reporters Without Borders has recorded a series of attacks on journalists in Catalonia since 2017. As the organisation notes, covering quarrels and demonstrations in Barcelona “has become a high-risk task for reporters”. It adds that insults, the throwing of objects, shoving and all kinds of physical and verbal aggression have become routine, especially during live television broadcasts.

The women’s movement can cause the bravest of reporters to duck into a corner. In May 2019, feminist magazine Pikara made a podcast with a midwife, Ascensión Gómez López, about childbirth. June Fernández, founder of Pikara, tweeted a quote from the midwife to promote the podcast: “The epidural turns childbirth into a silent act, disconnected from the body. In childbirth we groan, as with orgasms. But silence is more comfortable in an aseptic environment.”

Two days later, the tweet received more than 1,200 replies, mostly from outraged women, as well as comments from magazine contributors. “Idiots”, “Irresponsible” and “You contribute to worsening the women’s situation” were some of the responses. It was a week in which Pikara was preparing a crowdfunding campaign. “What if lots of people decide not to support us?” Fernández wrote in an article. She told how staff had discussed whether they should have self-censored, as journalists who do not self-censor face the prospect of losing support. But she argued that self-censorship was not a route they wanted to go down.

That was not Pikara’s first controversy. A previous one came when it interviewed a porn star, Amarna Miller. Following much criticism, the magazine issued a letter to readers to justify the decision, and lost a subscriber. The publication also became embroiled in a debate after publishing an opinion piece arguing against breastfeeding.

Pikara’s experience illustrates the power that an audience’s opinion has over editorial decisions. Even feeling the need to state openly that it will not self-censor says a lot.

Andrea Momoitio, a journalist with Pikara, told Index about the intense “agitation around certain movements” and worried that the “media are heading towards niche journalism”. She added: “The more specialised the public is, the more we know their interests, the harder it is to do independent journalism.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” size=”xl”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalists working in Catalonia for national media, such as television channels Antena 3 and La Sexta, are branded as “manipulators” by pro-independence social movements” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As editor-in-chief of local newspaper La Opinión in Murcia, Lola García selects content every day.

“Sometimes journalists cannot detach themselves from what surrounds them, so it is easy to get carried away. We need to be more alert than ever,” said García.

“Everything is polarised and, on many occasions, it is necessary to take sides. The key is to do it with truthful and fact-checked information.”

Indeed, the polarisation of Spanish politics, which became evident with extreme right-wing party Vox getting 52 seats in parliament last November, has been reflected in the media. Outlets show marked ideologies and provoke opposing and radical opinions.

In certain cases, this exaltation of ideology turns journalists into advocates for one side or the other. “The role of journalists as analysts is being left aside,” Momoitio said.

This also happens when pitching ideas for pieces or investigations.

Investigative journalist Paula Guisado, who works for national newspaper El Mundo, thinks the difference between self-censorship and a simple choice of content is “very subtle”.

“In my case, it’s a matter of knowing what the media outlet I work for prefers to publish. I invest my time in pitching topics I know will be better received. In corruption scandals, for instance, we all know El Mundo prefers to talk about PSOE [the left-wing party now in power] and El País would rather investigate [the right-wing] PP.”

Rather than seeing this as self-censorship, Guisado says it is “taking advantage of the environment you are working in”.

But García said: “When decisions are made based on non-journalistic criteria, it is self-censorship. When media business, ideology or other interests come into play, the pressure on journalists is intense.”

Job insecurity lies at the heart of this issue. The aforementioned 2016 Annual Report of the Journalistic Profession noted this pressure comes mostly from “people related to ownership or management of the media outlet”, especially when it comes to freelancers. In addition, failing to give in to the pressure can lead to consequences including, in many cases, being dismissed.

Luis Palacio Llanos, who oversees these reports, sees a possible relationship between the precariousness of the industry and self-censorship. “Between 2012 and 2018, and probably before that, unemployment and job insecurity was the main professional concern for Spanish journalists, according to our annual surveys. In 2019, this fell to second place, surpassed by bad pay, another sign of a precarious industry. In addition, journalists always rated their independence when carrying out their job below 5 on a scale of 0 to 10. Over the past few years, less than a quarter of journalists stated they had never been pressured to change significant parts of their pieces.”

The financial crisis that began in 2008 had a lot to do with the rise of self-censorship among journalists. The fall in advertising caused thousands of layoffs and the closure of hundreds of media operations. By 2012, more than 6,200 journalists had lost their jobs, according to the Spanish Federation of Journalist Associations. By 2014, 11,145 journalists had been fired and 100 media outlets had closed.

Momoitio believes the crisis and self-censoring go hand in hand. “The audience demands a very compassionate journalism, which does not take you out of your comfort zone. Journalism is going through such a long crisis that it has to adapt to these requests.”

Palacio added: “Surely the crisis and the deterioration in working conditions have been the main factors in the increase in self-censorship. This has been superimposed on a structural crisis that began at the end of the 20th century alongside the expansion of digitalisation.”

Digital is, of course, another aspect. Social media was central to the Pikara episode. In a time when information reaches millions of people in a matter of seconds, the reaction of a large digital audience can make journalists more vulnerable – and cautious.

“Social media greatly promotes self-censorship,” said Momoitio. The audience “follows you because you tell the stories they want to hear, from their perspective. That is very dangerous and irresponsible”.

García added: “Social media is a double-edged sword. There is greater projection, but it can trigger uncontrolled reactions.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Silvia Nortes is a freelance journalist based in Murcia, Spain

Index on Censorship’s spring 2020 issue is entitled Complicity: Why and when we chose to censor ourselves and give away our privacy

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Why and when we chose to censor ourselves and give away our privacy” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_column_text]The spring 2020 Index on Censorship magazine looks at how we are sometimes complicit in our own censorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”112723″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2020/03/magazine-complicity/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]