01 Dec 22 | Belarus, Campaigns, China, Equatorial Guinea, Iran, Mexico, News and features, Nicaragua, North Korea, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”120029″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]

At the end of every year, Index on Censorship launches a campaign to focus attention on human rights defenders, dissidents, artists and journalists who have been in the news headlines because their freedom of expression has been suppressed during the past twelve months. As well as this we focus on the authoritarian leaders who have been silencing their opponents.

Last year, we asked for your help in identifying 2021’s Tyrant of the Year and you responded in your thousands. The 2021 winner, way ahead of a crowded field, was Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, followed by China’s Xi Jinping and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad .

The polls are now open for the title of 2022 Tyrant of the Year and we are focusing on 12 leaders from around the globe who have done more during the past 12 months than other despots to win this dubious accolade.

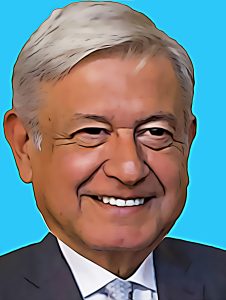

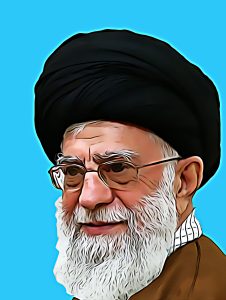

Click on those in our rogues’ gallery below to find out why the Index on Censorship team believe each one should be named Tyrant of the Year and then click on the form at the bottom of those pages to cast your vote. The closing date is Monday 9 January 2023.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120042″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-abdel-fattah-el-sisi-egypt/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Egypt” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-abdel-fattah-el-sisi-egypt%2F”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120032″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-ali-khamenei-iran/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Ali Khamenei, Iran” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-ali-khamenei-iran%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Ali%20Khamenei%2C%20Iran”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120034″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-alyaksandr-lukashenka-belarus/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Alyaksandr Lukashenka, Belarus” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-alyaksandr-lukashenka-belarus%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Alyaksandr%20Lukashenka%2C%20Belarus”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120038″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-andres-manuel-lopez-obrador-mexico/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-andres-manuel-lopez-obrador-mexico%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Andr%C3%A9s%20Manuel%20L%C3%B3pez%20Obrador%2C%20Mexico”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120039″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-daniel-ortega-nicaragua/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Daniel Ortega, Nicaragua” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-daniel-ortega-nicaragua%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Daniel%20Ortega%2C%20Nicaragua”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120033″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-kim-jong-un-north-korea/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Kim Jong-un, North Korea” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-kim-jong-un-north-korea%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Kim%20Jong-un%2C%20North%20Korea”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120036″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-min-aung-hlaing-myanmar/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Min Aung Hlaing, Myanmar” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-min-aung-hlaing-myanmar%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Andr%C3%A9s%20Manuel%20L%C3%B3pez%20Obrador%2C%20Mexico”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120035″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-mohammad-bin-salman-saudi-arabia/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Mohammad bin Salman, Saudi Arabia” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-mohammad-bin-salman-saudi-arabia%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Daniel%20Ortega%2C%20Nicaragua”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120043″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-hamad-al-thani-qatar/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, Qatar” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-hamad-al-thani-qatar%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Kim%20Jong-un%2C%20North%20Korea”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120037″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-teodoro-obiang-nguema-mbasogo-equatorial-guinea/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-teodoro-obiang-nguema-mbasogo-equatorial-guinea%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Andr%C3%A9s%20Manuel%20L%C3%B3pez%20Obrador%2C%20Mexico”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120041″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-vladimir-putin-russia/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Vladimir Putin, Russia” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-vladimir-putin-russia%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Daniel%20Ortega%2C%20Nicaragua”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”120044″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2022/12/tyrant-of-the-year-2022-xi-jinping-china/”][vc_custom_heading text=”Xi Jinping, China” font_container=”tag:h4|text_align:center” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2022%2F12%2Ftyrant-of-the-year-2022-xi-jinping-china%2F|title:Tyrant%20of%20the%20year%202022%3A%20Kim%20Jong-un%2C%20North%20Korea”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][ays_poll id=6][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

01 Dec 22 | China, Hong Kong

Xi Jinping has excelled with his tyrant credentials this year. Earlier this year, a controversial United Nations‘ report said that “serious human rights violations” have been committed in Xinjiang while Xi’s government is behind moves to repress Uyghurs living in Europe.

Xi Jinping has excelled with his tyrant credentials this year. Earlier this year, a controversial United Nations‘ report said that “serious human rights violations” have been committed in Xinjiang while Xi’s government is behind moves to repress Uyghurs living in Europe.

Xi has also now started a third term in power, after a 2018 change to the country’s laws to end the previous two-term limit. Tyrants just love to rip up the rule book when it comes to clinging to power.

“My nomination for Tyrant of the Year 2022 goes to the man who somehow made us all feel sorry for Hu Jintao when he snubbed the former Chinese Communist Party leader back in October, a remarkable feat given that Hu isn’t exactly an ally when it comes to human rights and free speech,” says Index on Censorship’s editor-in-chief Jemimah Steinfeld.

Xi’s policies are increasingly being called into question.

“His Zero Covid policy is as barmy as it is draconian. It’s led to the deaths of many who have not been able to get urgent medical treatment, been locked in their apartments when they’ve caught fire, have taken their own lives out of desperation,” says Steinfeld.

The protests against his policy (and indeed his legitimacy) showed a kink in Xi’s armour but he responded in true autocratic style – arrests, arrests and more arrests (plus a raft of other silencing measures).

“The CCP’s unofficial promise to make people’s lives materially better in exchange for fewer political freedoms has been broken,” says Steinfeld. “Unemployment is high and people are miserable and yet his merciless reign shows no signs of getting easier.”

01 Dec 22 | Russia

Vladmir Vladimirovich Putin is the tyrant’s tyrant in more ways than one. Over the two decades he has dominated Russian politics as president and prime minister, he has set a new standard in the brutal oppression of opponents at home and abroad. His illegal invasion of Ukraine on 24 February has had a devastating effect on the global economy and turned Russia into a global pariah. But he has also been a consistent champion of other tyrants, whether it is Ayatollah Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran, President Assad of Syria or his closest ally in the region, President Lukashenska of Belarus.

Vladmir Vladimirovich Putin is the tyrant’s tyrant in more ways than one. Over the two decades he has dominated Russian politics as president and prime minister, he has set a new standard in the brutal oppression of opponents at home and abroad. His illegal invasion of Ukraine on 24 February has had a devastating effect on the global economy and turned Russia into a global pariah. But he has also been a consistent champion of other tyrants, whether it is Ayatollah Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran, President Assad of Syria or his closest ally in the region, President Lukashenska of Belarus.

The horrors perpetrated by the army sent to Ukraine in 2022 by Putin are too many to catalogue here. But they include torture and summary execution, as evidenced from the mass graves of Bucha, the forced deportations of citizens of occupied territories in the east of the country, indiscriminate attacks on civilian targets such as the maternity hospital in Mariupol and sexual violence used as a weapon of war. As winter sets in his forces have targeted power facilities, leaving many Ukrainians without light, heat and water in freezing conditions.

Meanwhile, in Russia itself the independent media has been crushed, with many journalists silenced or forced into exile. New legislation has turned protesters into traitors. Even calling Russia’s intervention in Ukraine a war has been deemed a crime, with anyone convicted of spreading “false information” facing a 15-year prison sentence.

“Most tyrants only brutalise their own people or the countries they invade. But Putin is a truly global tyrant who has made the whole world a poorer place by strangling the supply of Russian oil and gas and Ukrainian grain. And he has made it a more dangerous place by bringing the threat of nuclear war to Europe. Tyrant of the year? More like tyrant of the century,” says Index’s editor-at-large Martin Bright.

01 Dec 22 | Equatorial Guinea

Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo may not be an obvious choice for our 2022 ‘Tyrant of the Year’, but he certainly wins awards for many aspects of his dictatorial reign. Gaining power before three of his fellow inductees on this list were even born, he’s now entered his sixth decade as the leader of Equatorial Guinea and is currently the longest serving president in the world.

Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo may not be an obvious choice for our 2022 ‘Tyrant of the Year’, but he certainly wins awards for many aspects of his dictatorial reign. Gaining power before three of his fellow inductees on this list were even born, he’s now entered his sixth decade as the leader of Equatorial Guinea and is currently the longest serving president in the world.

“Anybody looking at Obiang’s 95% share of the recent national elections vote may think he’s an electoral powerhouse. However, with little political opposition and a heavily controlled press, it’s far from a free democratic choice for most,” says Francis Clarke, editorial assistant at Index on Censorship.

While elections are regular, the one held in November 2022 ‘returned’ Obiang to his sixth term in office. While opposition is nominally allowed alongside a multi-party system, he has near total control of the West African nation. Before the 2017 legislative election, it was reported that opposition party supporters were arrested, polling stations closed earlier than advertised and people were limited from reaching distant polling stations.

In September, a human rights campaigner was arrested by police and held for at least 18 days for assisting opposition activists in the country. Anacleto Micha Nlang, co-founder of the banned rights group Guinea is Also Ours, was delivering food to families held under siege in the offices of the outlawed Citizens for Innovation (CI) party. In 2021, an exiled investigative journalist was the subject of threats following the publication of an article alleging corruption at the highest level in his home country.

An oil-rich state, the elite of the country are thought to have plundered the proceeds from this natural resource. In 2017 Obiang’s eldest son, vice-president of the country at the time, was convicted of embezzling millions of dollars from his government and laundering the money through France. He was handed a three-year suspended prison sentence and a $35 million fine.

“With the President’s reign likely to continue, and then passed on to his son, there is currently no sign of a name other than Obiang to be installed as the leader of the nation,” says Clarke.

01 Dec 22 | Qatar

The atrocious worker conditions and contempt for basic human rights in Qatar have certainly been on our minds over the last year. However, relatively little attention has been paid to the man pulling the strings.

The atrocious worker conditions and contempt for basic human rights in Qatar have certainly been on our minds over the last year. However, relatively little attention has been paid to the man pulling the strings.

“Al Thani holds a relatively lower profile than his counterparts in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, but his dedication to censorship is no less concerning. From concealing thousands of workers’ deaths due to poor working conditions to arresting both local and international journalists, Al Thani remains committed to curtailing freedom of expression at every level,” says Emma Sandvik Ling, partnerships and fundraising manager at Index on Censorship.

Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani became emir in Qatar in 2013. Since then, he has demonstrated a commitment to censoring dissident voices. Qatar boasts widespread censorship in the press, academia, and civil society. Blatant cases of censorship are certainly not hard to come by: In 2021, blogger Malcolm Bidali was arrested and spent 28 days in solitary confinement for writing critically about the Qatari royal family. Indigenous groups are excluded from participating in Shura Council elections. In November, two Norwegian journalists were arrested hours before a scheduled interview with Abdullah Ibhais, the former communications director for Qatar’s 2022 World Cup.

Like his regional counterparts, Al Thani has invested in soft power strategies to appease international critics. Index editor-in-chief Jemimah Steinfeld reflected on the 2022 World Cup in Qatar in the autumn edition of the Index on Censorship magazine: “Here’s a nation that prohibits homosexuality, has no free press, forbids protest, restricts free speech. It has stadiums built using migrant labour with little to no workers’ rights. And yet come November these stadiums will open to the world, international dignitaries will be wined and dined and Qatar will revel in the glory associated with hosting a World Cup.”

Global attention will likely move on to new issues and challenges after the World Cup final on 18 December. Still, Al-Thani’s oppressive regime will remain.

01 Dec 22 | Saudi Arabia

“Mohammed bin Salman should be awarded the title of ‘tyrant of the year’ not only because of his track record of censorship and suppression, but also because of the potential for violent tyranny to come” says Emma Sandvik Ling, partnerships and fundraising manager at Index on Censorship.

“Mohammed bin Salman should be awarded the title of ‘tyrant of the year’ not only because of his track record of censorship and suppression, but also because of the potential for violent tyranny to come” says Emma Sandvik Ling, partnerships and fundraising manager at Index on Censorship.

At only 37 years old, Mohammed bin Salman, colloquially referred to as MBS, is the youngest of the tyrants on our list. He therefore has the potential to offer a suppressive regime for decades to come.

In 2022, MBS celebrated his appointment as prime minister. The crown prince and de facto ruler has held various political positions since he became minister of defence in 2015, though his father King Salman bin Abdulaziz, 86, still holds the throne.

While Saudi Arabia is committed to a more liberal, globalist image, those calling for freedom of expression still face harsh punishments. In October, three members of the Al-Huwaiti tribe were sentenced to death for resisting eviction caused by the $500 billion NEOM development. Meanwhile, the University of Leeds student Salma al-Shehab has been sentenced to 34 years in prison for retweeting Saudi activists. On 12 March, 81 men were executed for “terrorism and holding deviant beliefs” including 41 who were believed to be minority Shia Muslims who took part in anti-govenrment demonstrations in 2011. Women, minority groups, activists, and journalists alike face severe consequences for speaking out against the regime.

Adding insult to injury, Bin Salman’s behaviour appears to be tolerated – if not accepted – internationally. In November 2022 the US State department granted the crown prince diplomatic immunity from prosecution over the brutal assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. This is despite President Biden’s repeated assurance that he would hold MBS accountable for his involvement. Due to Saudi-Arabia’s important financial and strategic ties, MBS looks poised to rule for years to come.

“As the world watches on, bin Salman continues to exert power in horrific ways. His rule will likely continue to restrict basic freedoms in Saudi Arabia and beyond,” says Sandvik Ling.

01 Dec 22 | Burma

“As a child Aung San Suu Kyi was a celebrated heroine in my family home and Myanmar, an authoritarian regime determined to squash democracy. For a few years there was hope, although not for the Rohinghya community (thanks to Min Aung Hlaing), until the military coup of 2021,” says Index on Censorship CEO Ruth Anderson.

“As a child Aung San Suu Kyi was a celebrated heroine in my family home and Myanmar, an authoritarian regime determined to squash democracy. For a few years there was hope, although not for the Rohinghya community (thanks to Min Aung Hlaing), until the military coup of 2021,” says Index on Censorship CEO Ruth Anderson.

In February 2021 Min Aung Hlaing seized power – declaring himself commander-in-chief of Myanmar and consolidating all political power into the State Administration Council – a body which he also chairs. He has since sought to quash all dissent. Challenge is not tolerated, politicians have been arrested and imprisoned on spurious charges. Since the coup 2,530 civilians have been killed by the military, 13,000 people remain in detention and 128 political prisoners have been sentenced to death, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

In a series of court cases since the military coup, former leader Aung Sun Suu Kyi has now been sentenced to 26 years’ imprisonment.

“These acts alone would warrant his crown as Tyrant of the Year but when you also consider his personal treatment of the Rohingya community then it’s difficult to see how anyone else qualifies for the title,” says Anderson. “Even before the coup Min Aung Hlaing was accused of acts of genocide against the Rohinghya minority – over one million Rohingya have been forced to flee Myanmar, and available data suggests that over 24,000 Rohingya have been systematically murdered by the state, over 18,000 women and girls raped and 36,000 thrown into fires. All by direct order of Min Aung Hlaing. The UN has declared that he should be tried for war crimes at the Hague. This man is a tyrant by every definition.”

01 Dec 22 | North Korea

“As far as freedoms go, there is no landscape so bleak as North Korea,” says Index assistant editor Katie Dancey-Downs. “Under Kim Jong-un’s totalitarian regime, citizens are fed propaganda in lieu of actual food. And as for elections? The ballot paper has only one option.”

“As far as freedoms go, there is no landscape so bleak as North Korea,” says Index assistant editor Katie Dancey-Downs. “Under Kim Jong-un’s totalitarian regime, citizens are fed propaganda in lieu of actual food. And as for elections? The ballot paper has only one option.”

Kim Jong-un continues to rule as the supreme leader of North Korea, keeping alive the brutal legacy of the Kim dynasty. He makes a grand show of nuclear weapons on the global stage (including recently firing more than 20 missiles across the sea border with South Korea) while much of the country lives in extreme poverty and under close surveillance. One of Kim’s most recent photo opportunities was alongside what is believed to be an intercontinental ballistic missile – he watched as the test was launched.

Criticism of the regime is not tolerated. Dissent is punished severely. Executions and prison camps drive fear under this totalitarian regime, while lavish displays of affection are demanded by its leader.

“North Koreans are nothing short of modern-day slaves who have been deprived of freedom of expression and movement,” says Jihyun Park, a UK-based activist who escaped from North Korea – twice. “North Korea is a place where I lived like a machine and remained silent.”

North Korea lands in last place in the Reporters Without Borders’ press freedom index, out of 180 countries. Only official government news sources are permitted, which are packed with propaganda. No outside information gets in, and what the rest of the world gets to see is controlled with the tightest of grips. Some tyrants might overreach on internet clampdowns, but for Kim it’s all or nothing. North Koreans only have access to a localised intranet, with absolutely no view of the world wide web in any form.

With Kim Jong-un the third generation in the dynasty, and talks of his eventual successor hotting up, Dancey-Downs comments: “Perhaps beyond simply Tyrant of the Year, Kim should be up for a lifetime achievement award.”

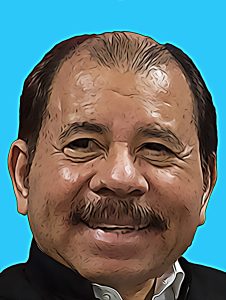

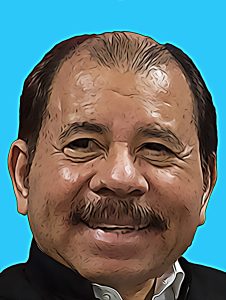

01 Dec 22 | Nicaragua

There is nothing more disappointing (or predictable) than a revolutionary hero turned tyrant. In the great tradition of Lenin and Castro, Ortega promised a new dawn as the leader of the rebel Sandinista National Liberation Front which opposed the Somoza family dictatorship in the late 1970s.

There is nothing more disappointing (or predictable) than a revolutionary hero turned tyrant. In the great tradition of Lenin and Castro, Ortega promised a new dawn as the leader of the rebel Sandinista National Liberation Front which opposed the Somoza family dictatorship in the late 1970s.

Ortega first took power in 1979 after the overthrow of the regime and served until 1990, first as the head of the Junta of National Reconstruction and then as President. After an absence of 17 years, he was re-elected in 2007 and has remained in office ever since. His rule has become increasingly brutal with crackdowns on his former political allies and opponents to his autocratic methods.

Protests against his regime began in 2014 over plans to grant a concession to a Chinese businessman to build the Nicaragua Canal. Protests were led by local campesinos whose faced the expropriation of their land. Further protests by indigenous people who blamed the government for forest fires flared in 2018 and compounded by opposition to tax increases and benefit reductions.

According to Human Rights Watch, Ortega has dismantled nearly all institutional checks on his presidential power. Opposition parties were banned in advance of the 2021 presidential elections and opponents imprisoned. Civil society has been neutered and an estimated 2,000 NGOs closed down with organisations receiving funding from international sources labelled as foreign agents. Over 100 journalists have been forced into exile in Costa Rica along with an estimated 80,000 asylum seekers.

In elections held in November 2022, the Sandinista Liberation Front announced it had won control of all 153 municipalities in the country. The result was inevitable after the banning of all opposition parties.

“For his critics, the Nicaraguan president has recreated a family dictatorship on the lines of the hated Somozas. His vice-president Rosario Murillo would disagree. She described the recent elections as ‘an exemplary, marvellous formidable day in which we confirm our calling for people.’ But then she is Ortega’s wife,” says Index’s editor-at-large Martin Bright.

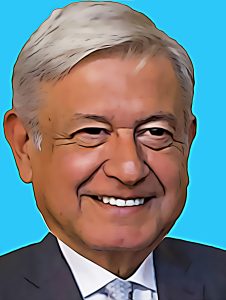

01 Dec 22 | Mexico

“He who has nothing to hide, has nothing to fear”. These were the words uttered by the Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador in a February 2022 press conference held the day after Heber López Vásquez, founder and director of the digital news outlets NoticiasWeb and RCP Noticias, was shot and killed. However this was not a call for greater transparency and action to respond to the ever-climbing rate of journalist murders in Mexico. He was publishing what he alleged were the confidential financial details of leading journalist, Carlos Loret de Mola, in response to the journalist’s reporting.

“He who has nothing to hide, has nothing to fear”. These were the words uttered by the Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador in a February 2022 press conference held the day after Heber López Vásquez, founder and director of the digital news outlets NoticiasWeb and RCP Noticias, was shot and killed. However this was not a call for greater transparency and action to respond to the ever-climbing rate of journalist murders in Mexico. He was publishing what he alleged were the confidential financial details of leading journalist, Carlos Loret de Mola, in response to the journalist’s reporting.

“This act of intimidation and the abuse of the presidential office would be egregious in any circumstance. However In Mexico, against a backdrop of rampant impunity and one of the worst track records for the safety of journalists, it is far worse than that,” says Index’s policy and campaigns officer Nik Williams. “According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 151 journalists and press workers have been killed in Mexico since 1992. The causes of these murders are complex; but a messy tangle of narco-politics, organised crime, corrupt police and state officials and runaway impunity has made Mexico one of the most dangerous locations to be a journalist outside a warzone. In fact, so far in 2022, Mexico is second only to Ukraine for the number of journalists killed.

Since Obrador only came to power in 2018, it would be overly-simplistic to lay this solely at his feet. However, according to Article 19, attacks on the press have increased by 85% since he took power, with every single Mexican state witnessing such incidents for the first time in 2021.

When there is a culture of impunity and the devaluing of journalists, the scene is set for violence. It is this erosion of the civic fabric that makes Article 19’s director for Mexico and Central America: “His [Obrador’s] speech causes other political actors to replicate his attacks. These actors feel empowered and allowed to attack in the face of a narrative that presents the press as an adversary. We are in a war speech, where the enemy must be annihilated.”

After publicly leaking Carlos Loret de Mola’s alleged salary and potentially violating Article 16 of the Mexican Constitution in the process, Obrador labelled journalists who are critical of him as “thugs, mercenaries, sellouts” and “the real mafia.” This framing establishes a false and dangerous parallel between the free press and criminal enterprises, further emboldening threats that can soon escalate to violence.

Impunity, the like of which is found in Mexico, requires significant and proactive action to address. It is not something that will just right itself when no one is looking. It requires a commitment to the value of free expression. It requires action. According to Human Rights Watch, “[o]f the 105 investigations into killings of journalists conducted by the federal Special Prosecutor for Crimes Against Freedom of Expression (Feadle), since its creation in 2010, just six have led to homicide convictions.” What good is a dedicated prosecutor if the rate of convictions is so low? Not only is this a failure to the family, friends and colleagues of the murdered journalists whose killings are being investigated by Feadle, this is a signal to those seeking to silence critical reporting: you can continue uninterrupted and undisturbed. This weakening of the mechanisms by which journalists can be protected is also seen in the 2020 decision of the Mexican Congress and supported by Obrador, to eliminate the independent funding that supported the Federal Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists. Now the mechanism is dependent on the Interior Ministry to pay for protection measures, but funds have been consistently cut. Leading media freedom organisations and 14 members of US Congress have raised concerns about this, seemingly to no avail.

Williams says: “What Obrador sees as a war against the elites, we see as a war against journalists, and ultimately free expression. Without Obrador stepping forward and addressing the ingrained climate of fear and impunity, instead of fixating on those who report on uncomfortable facts, Mexican journalists will remain stuck in the crosshairs of those seeking their silence.”

01 Dec 22 | Belarus

“You can usually tell the quality of a tyrant’s credentials by the number of people he has thrown in jail on spurious grounds and Europe’s last dictator, Alyanksandr Lukashenka, is no exception,” says Index associate editor Mark Frary.

“You can usually tell the quality of a tyrant’s credentials by the number of people he has thrown in jail on spurious grounds and Europe’s last dictator, Alyanksandr Lukashenka, is no exception,” says Index associate editor Mark Frary.

Lukashenka started his fifth term as president in August 2020, following an election that most credible observers believe was neither fair nor free.

According to the human rights organisation Viasna, the list of political prisoners has now grown to 1,442 people. “This includes our former Index colleague Andrei Aliaksandrau and his wife Irina Zlobina, who were sentenced to 14 years and nine years respectively in early October for ‘establishing an extremist formation’,” says Frary.

It seems that even the slightest hint of opposition to Lukashenka can see you head off to the country’s infamous prisons. In November, 69-year-old teacher Ema Stsepulyonak was given a two-year sentence for supposedly insulting the Belarusian leader following a police shoot-out at a Minsk apartment that left two people dead.

Lukashenka is clearly worried by such “extremists”. His government has started a growing list of people who are considered as such and anyone appearing on it are not allowed to hold public office, teach, publish writing or participate in military service. On one day at the end of October, Lukashenka’s regime added a frankly ridiculous 625 extremists to the list. “Belarus must be so dangerous with this many extremists, right?” asks Inna Kavalionak of Politzek.me in the winter 2022 edition of Index on Censorship magazine.

“Lukashenka’s fate is closely tied with that of his friend and neighbour Vladimir Putin,” says Frary. “In the illegal war in Ukraine, Lukashenka has allowed Belarus to be used as a launchpad for Russia’s soldiers into the country’s northern flank. He has also promised that ‘Europe will tremble’ if Belarus is attacked.”

By aligning himself with Putin, Lukashenka is firmly planting himself on the wrong side of history.

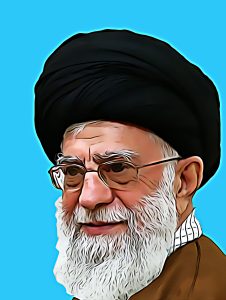

01 Dec 22 | Iran

If you were in the Iranian capital Tehran on Friday 23 September, you would be forgiven for thinking that Ali Khamenei was a popular and misunderstood leader. That day, thousands of Iranians marched through the city waving Iranian flags and holding high photos of Khamenei and his predecessor Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

If you were in the Iranian capital Tehran on Friday 23 September, you would be forgiven for thinking that Ali Khamenei was a popular and misunderstood leader. That day, thousands of Iranians marched through the city waving Iranian flags and holding high photos of Khamenei and his predecessor Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

“This is a classic from the authoritarian playbook,” says Index’s associate editor Mark Frary. “How often do you see such pro-government rallies in truly free countries? You have to wonder what pressure they bring to bear on the people present to agree to take part in events which are clearly designed to drown out true protests.”

The September rallies were a largely unsuccessful attempt, at least outside Iran, to distract attention from widespread protests in the country following the death in custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, detained by Iran’s notorious Gasht-e Ershad.

“These so-called ‘morality police’ uphold respect for Islamic morals, including detaining women who they see as being improperly dressed, such as wearing revealing or tight-fitting clothing or not wearing the required hijab,” says Frary.

Since then the country has been wracked by protests, which have been violently subdued. Oslo-based NGO Iran Human Rights say that a minimum of 448 people, including 60 children, have been killed in the protests. Many of those paying the ultimate price for protest have been women.

The Iranian authorities have been trying to keep a lid on the news by shutting down the internet in the country. Iran’s parliament has also been working on a draft bill that seeks to impose further restrictions on internet access for people in Iran, including criminalising the use of virtual private networks.