22 Aug 17 | media freedom featured

Smears about the media made by US President Donald Trump have obscured a wider problem with press freedom in the United States: namely widespread and low-level animosity that feeds into the everyday working lives of the nation’s journalists, bloggers and media professionals.

Index on Censorship published a report on media freedom in the US, documenting violations, limitations and threats to journalists from across the country in the six months leading up to the presidential inauguration and the months after. The research indicates that American media workers face pressure on a daily basis. Hannah Machlin, the project manager of Mapping Media Freedom, discusses how threats to US press freedom go well beyond the Oval Office.

Margaret Flynn Sapia spoke to Mapping Media Freedom Project Manager Hannah Machlin.

What is Mapping Media Freedom and how does it work? How does it relate to US Press Freedom Tracker?

Machlin: Mapping Media Freedom is a platform which documents all threats, violence and limitations to press freedom in Europe. The platform follows a strict two step Reuters-style verification system. For each reported incident, we require two to three independent sources which verify the location, subject matter and details of the censorship or confrontation. We gather this information by reviewing police statements, court documents and local news stories along with speaking to regional journalists. After the details have been verified, the report is edited for grammatical accuracy and clarity and is reviewed a final time by the project’s manager. The US Press Freedom Tracker also aims to track and analyse violations that are occurring in the United States.

What type of incidents does Mapping Media Freedom and the US press freedom tracker project cover?

Machlin: We report on a wide range of threats that affect journalists from doing their jobs such as violence, intimidation tactics and imprisonment. This also includes legislation and legal charges. Media professionals face dozens of hazards on a daily basis, so we do our best to cover any and all risks and retaliation they confront.

Do you include journalist related incidents even when they appear to be unrelated to the journalist’s work?

Machlin: If we can prove an incident is unrelated to a journalist’s work, it is not a fit for Mapping Media Freedom or the US press freedom tracker. However, journalists frequently face trumped up charges intended to silence or discredit them – like Canadian journalist Ed Ou who was detained at the US border without lawful reason on his way to cover a protest. Subsequently, we take extra care to review all of our reports on a case by case basis.

What are the most common difficulties you encounter in monitoring violations to press freedom?

Machlin: It’s difficult to depict an accurate image of the increasingly wide range of intimidation tactics used against journalists. For example, in the US, we documented that journalists have frequently been prevented from doing their job by government officials who have blocked reporting on President Trump’s campaign and various White House briefings. In addition to the onslaught of governmental targeting, the intimidation and attacks on media freedom are increasingly carried out by private individuals – either in person or online.

What most surprised you in Index’s report on US media freedom?

Machlin: The deterioration of press freedom in the US is nothing new. Under the Obama administration, a record number of whistleblowers were prosecuted and detained for their reporting. Moreover, we’ve seen rising levels of intimidation tactics used against journalists while reporting on demonstrations, including the Dakota Access Pipeline and the Black Lives Matter protests. Most recently, as the US Press Freedom Tracker reported, journalists were subjected to violence while covering protests in Charlottesville. Overall, threats to press freedom in the US are increasingly disturbing, and the US Press Freedom Tracker project’s goal is to continue shedding light on this increasingly disturbing trend and provide data for advocacy organisations.

Which findings of Index’s US media report do you think are most important?

Machlin: It doesn’t matter whether you are an independent reporter or an established news organisation – all American media workers face significant and undue risks on a daily basis. While freelancers traditionally lack the protection of established media outlets and thereby face a greater degree of risk, even large media organisations can be driven out of business if they rival the rich and powerful. This report has demonstrated that the threats to free media are deeply rooted.

18 Aug 17 | News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship has recruited a new youth advisory board to sit until December 2017. The group is made up of young students, journalists and researchers from four continents.

Each month, board members meet online to discuss freedom of expression issues around the world and complete an assignment that grows from that discussion. For their first task the board were asked to write a short post about a pressing freedom of expression issue from their countries of residence.

Sean Eriksen – Brisbane, Australia

Eriksen is a 21-year-old Arts/Law student majoring in history and international relations

Notwithstanding the aphorism that ‘if free expression is to mean anything then it must protect unpopular opinions’, censorship is most tolerable at the fringes; and it is a mark of social progress that bigotry is considered so unpopular that many countries have tried to legislate it out of existence. But the suggestion that hate speech laws represent a positive cultural development does not endear them to those who believe free expression is inherently sacrosanct.

Section 18C(1)(a) of Australia’s federal Racial Discrimination Act 1975 prohibits acts that are reasonably likely to ‘offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or group of people’ based on their race, colour, or national or ethnic origin. This allows administrative review and ultimately litigation, giving judges a wide capacity to make rulings on acceptable public discourse.

Defenders of the law claim that sufficient legislative exemptions protecting artists, commentators and academics exist elsewhere in the legislation, but in practice the standard for offence has not been particularly high. Most famously in Eatock v Bolt, articles by a conservative columnist were prohibited from further publication because he had suggested that many people were identifying as indigenous solely because it had become trendy to do so. This is perhaps a crass point to make, but not one that adults cannot reasonably be exposed to.

Though it may be meant well, the censorship of ugly or even disturbing speech is still censorship. Bad ideas do exist and the only harm is in hiding them.

Adam Rossi, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Adam Rossi – Vancouver, Canada

Rossi is a Canadian student pursuing an MA in International Relations. He recently spent a year teaching English in Barcelona, Spain

Seven years after Catalonia’s government outlawed bullfighting in the autonomous region, its officials now find themselves back in the ring. They’ve been thrown in with a great bull, the Spanish government, which has been trying to skewer any Catalan public figure expressing pro-independence views as if they were matadors clad in red.

They have already suspended, fined, and barred from office the former Catalan prime minister, some of his cabinet members, and city councillors for organising a mock referendum back in 2014 and for continually speaking publicly about their belief in the need for real independence. Joan Coma, a leftist city councillor of the Catalan CUP party, now faces an eight-year prison sentence with his passport confiscated for saying, “To make an omelet, you must break some eggs,” in a discussion on independence. Spanish authorities claim that this was a call for political violence. Meanwhile, Spanish President Manuel Rajoy has even threatened to use force to stop the referendum. Not allowing the vote to happen would be undemocratic, essentially ignoring the voice of the people. In addition, these targeted shots at individual citizens such as Joan Coma only serve to drag Spain back to a dark past of civil oppression. They are even using the Francoist penal code to charge Coma. However, these acts only seem to be fuelling the hearts of Catalans, as street demonstrations and “si” vote flags begin to fly proudly outside people’s homes. The current Catalan president, Carles Puigdemont, says the vote will happen regardless, and that the Catalan government will be prepared for immediate separation if the result is a “yes.”

Huw Roberts, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Huw Roberts – Hampshire, UK

Roberts graduated from Durham University in June 2017 with a BA in Politics. He has been granted a scholarship to study Public Administration at Shanghai Jiao Tong University

In May 2016 major social media firms, including Facebook and Twitter, signed up to a voluntary code of conduct aimed at combating illegal hate speech. This agreement, in partnership with the European Commission, required the signees to remove hate speech posted on their platform within a twenty-four hour period. Since this deal, the pressure placed on these companies to remove hate speech has been increasing, with proposals forwarded by European Union member states for binding legislation and punitive fines. Undoubtedly, the scope for the facilitation and proliferation of hate speech on these platforms requires a response, however, the current demands being placed on social media firms are fostering policies which often lack refinement and curtail legitimate free speech.

Leaked documents from earlier this year revealing Facebook’s hate speech policies typify the problems censorious practices can raise for free expression. The leading headline from these documents was that white men (as a group) were considered a protected category, yet, black children were not. As such, under Facebook guidelines attacks directed against white men were required to be removed, whilst those targeted at black children were permissible. This policy would not only seem discriminatory towards those most vulnerable within society, but has also proven detrimental to discourse. For example, campaigners from social justice groups such as Black Lives Matter have found their accounts blocked due to criticising structural privileges held by white men. Without an overhaul of the current guidelines in place and a more nuanced approach to censoring hate speech, those most marginalised within society risk having a vital outlet for raising debate and challenging inequalities shut down.

Madara Melnika, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Madara Melnika – Riga, Latvia

Madara is a law student at University of Latvia. She has also studied in Salzburg and Berlin

At the beginning of July 2017 one of the most popular sports commentators in Latvia, Armands Puče, was dismissed from covering the Latvian Kontinental Hockey League club Dinamo Riga’s games. Although he was dismissed by the private media enterprise MTG TV Latvia, this case is noteworthy as the journalist claims that the decision on his dismissal was taken after the company received an ultimatum from the KHL bureau in Moscow, threatening to end the KHL’s broadcasting agreement with MTG TV unless Puče was removed.

His colleagues hinted that “just like in Soviet times”, all of the articles written by Puče in his parallel work as a journalist, in which he criticised the political ideology of the KHL and its impact on Dinamo Riga, had been translated into Russian and sent to the KHL main bureau in Moscow. It is important to stress that the mentioned articles were not connected to his hockey broadcasts.

After some time, the media enterprise claimed that its cooperation with Puče was ended due to plans for a new show concept, which would include also changing the anchor of the broadcast. Thus Puče, who had led the Hockey studio ever since the first season of the renewed hockey club Dinamo Riga, had to be let go.

Of course, the commentator is connected to his media employer and represents it. However, can the fate and work opportunities of a sports commentator absolutely depend on his ideology and activities done outside work – and will the teams suddenly play better, if their games are covered by loyal commentators?

Daniel Penev, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Daniel Penev – Kyustendil, Bulgaria

Penev is a Bulgarian freelance journalist and a member of the Association of European Journalists

Valentin Todorov is a journalist from Novi Iskar, a town in western Bulgaria, who owns the local news website www.noviiskar.bg. He registered the website under this name in 2010. In June, Todorov learned that Daniela Raycheva, the mayor of the district since 2011, had challenged his right to use this domain. According to the general terms set out by Register BG Ltd., which administrates web domains in Bulgaria, the names of municipalities and regions are reserved for domains registered by the respective administrations. However, when the name is already in use, the parties wanting to use it must either choose another name or wait until it becomes vacant. Here comes the gist of the struggle: when he registered his website, Todorov secured a declaration in which Valentin Kotov, then mayor of Novi Iskar, explicitly states that he will not claim the name while it is active.

“There arises the question as to whether the public administration may, whenever it wishes, make claims in relation to something it has given away and which a citizen owns and has invested in for years,” the Association of European Journalists – Bulgaria wrote in July. “Trust is a media outlet’s greatest capital and it is inseparably connected to its name.”

Todorov suspects that the district mayor resorted to such actions because of the website’s more critical reporting on the various problems in the district. Notably, the mayor only decided to challenge his use of the domain six years after she took office. The administration also already has its own website, www.novi-iskar.bg. Todorov is optimistic about the outcome of the dispute, due by the end August, but if the Register BG commission rules in favour of the mayor, this will set worrying a precedent for all media outlets in Bulgaria.

Sophie Baggott, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Sophie Baggott – London, UK

Baggott is a journalist focused on promoting human rights

Another resounding voice has blasted proposed changes to the regime protecting official information in the UK, which would deem anyone who communicates information seen ‘to prejudice the United Kingdom’s safety or interests’ or anyone who ‘obtains or gathers’ such information as having committed an offence, potentially resulting in a jail sentence of up to 14 years. To what extent will our government listen to the outcry?

“The proposals threatened would be ‘both retrograde and repressive’”, said the News Media Association (NMA) in a 20-page document released at the end of July. The NMA, which speaks for national and regional UK news media, has highlighted the industry’s concerns about consultative proposals for changes to the Official Secrets Acts and the Data Protection Act, as well as to other unauthorised disclosure offences.

The proposed reforms would lead to ‘damaging and dangerous inroads into press freedom by making whistle-blowers, journalists and media organisations prime targets for state surveillance and criminal prosecution’, the NMA warned. The association said the changes would ‘extend and then entrench official secrecy’, adding: ‘It would be conducive to official cover up. It would deter, prevent and punish investigation and disclosure of wrongdoing and matters of legitimate public interest’.

Investigative journalism could endure a ‘chilling effect’, said the NMA, from how the changes would make it easier for the government to prosecute anyone involved in obtaining, gathering and disclosing information, even if no damage were caused, and irrespective of the public interest. The proposed reforms might also precipitate a more widespread use of state surveillance powers against the media under the guise of suspected media involvement in offences. This would pose a threat to confidential sources and whistle-blowers, the NMA noted.

Is the government going to reconsider or restrict? Either way, the media industry will certainly have to remain on high alert for the foreseeable future.

Dan Bateyko, youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Dan Bateyko – Sarasota, Florida

Bateyko is an internet rights researcher from Sarasota, Florida. He is currently travelling on a Watson Fellowship, a one-year purposeful grant for global independent study

U.S. Twitter users blocked by their twit president might have a remedy. On July 11, the Knight First Amendment Institute filed a lawsuit arguing that US President Donald Trump violated the First Amendment rights of dissenting citizens when he blocked them from reading his tweets and contributing their own. Speaking to Index, Katie Fallow, senior staff attorney at Knight Institute, distilled the issue:

“The president may be using social media in a new way, but the First Amendment principles at stake are longstanding. When the government sets up a public forum, whether on Twitter in a town hall, it can’t exclude people just because it doesn’t like what they have to say.”

But whether Trump’s Twitter account can be considered a public forum is a point of contention. As the Knight Institute argues, Trump’s account has all the hallmarks of a public forum; the account tweets news on policy and provides a platform for public debate. However, in a recent statement, the justice department rejoined that Trump’s editorial control over who to follow and block on his private account is not a constitutional issue.

I chose to highlight this case in my first blog post as a member of Index’s youth advisory board because social media is an incredible tool for giving citizens a voice, granting them a platform to exchange views and petition their public officials. But where and how free speech rights extend online is still far from clear—as Lyrissa Lidksy, dean of Missouri’ School of Law, writes, determining whether comment removal on government-sponsored pages is constitutional “requires close examination of the U.S. Supreme Court’s public forum and government speech doctrines, both of which are lacking in coherence – to put it mildly.” With clarity, public officials once reticent to tackle the thorny issue of public accounts could feel comfortable with more online civic engagement. And by establishing further precedent, the Knight Institute’s defense of Twitter users will hopefully protect people’s hard-fought rights to free expression online.

Isabela Vrba Neves youth advisory board, July-December 2017

Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm, Sweden

Vrba Neves is a journalist and writer based in Sweden, and a graduate from Kingston University London

Sweden is known for having a good track record when it comes to freedom of expression, and is regarded as being an example in democracy and equality. However, the Nordic country has recently been faced by a wave of threats by far-right groups attacking journalists and media organisations. In February 2017 journalist Evelyn Schreiber received hundreds of death threats and threats of sexual violence after questioning a Facebook post by Peter Springare, a police officer who heavily criticised immigrants for violent crimes.

Springare received support by far-right groups who went after Schreiber with messages and phone calls. In a radio interview Schreiber explained how she believed the threats were “organised” as she would receive a large amount of messages every time a far-right group shared her article on Facebook.

She also described how at first the groups mostly criticised her article, but then progressed to personal vulgar and sexist attacks towards her. The newspaper, Nerikes Allehanda, which published her article, reported the threats to the police.

An issue that Schreiber brings up with these kinds of incidents is that journalists may self-censor for their own safety, which in turn can threaten freedom of expression. To combat this, the Swedish government announced in July 2017 an action plan which aims to strengthen the preventative work towards hate and threats against journalists, artists and elected representatives.

The Swedish Victim Support and the Swedish Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority have been commissioned to develop material that will provide knowledge and support to those who have been under threat for participating in public conversations, in order to strengthen free speech and freedom of expression.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”More from the youth advisory board” category_id=”6514″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Aug 17 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Back Row from left: Adam Rajab, Malak Rajab and Nabeel Rajab. Front Row from left: Sumaya Rajab and Zainab Alkhawaja. (Photo: Adam Rajab)

Human rights defenders often confront obstacles that make their work difficult. This is especially true in Bahrain, where the Sunni monarchy and government have been bent on silencing all opposition ever since the Arab Spring when tens of thousands of Bahraini citizens protested for democratic reform.

In recent months, the nation’s only independent news outlet, Al Wasat, was shuttered and prominent human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was sentenced to two years in prison for “spreading fake news”.

The families of activists suffer along with their loved ones and are often targeted with official harassment: detention, loss of employment, beatings and harassment. Each case is an individual story of a struggle for freedom.

A result of actions

Members of Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei’s family have been harassed and detained due to his ongoing campaigning for democracy and human rights in Bahrain. Most recently his mother-in-law and brother-in-law were detained while Alwadaei attended the United Nations Human Rights Council in March.

Alwadaei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, is no stranger to detention: he was arrested twice in 2011 and served a six-month sentence in a Bahraini jail. He found asylum in the UK in July 2012. In February 2015, Alwadaei was among 72 Bahraini citizens to be stripped of their citizenship.

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei with his son Yousif (Photo: Moosa Satrawi)

In October 2016, Alwadaei’s wife and infant son Yousif also faced official harassment as they tried to leave Bahrain to join Alwadaei in the UK. His wife was arrested at the airport and held overnight, during which time she was ill-treated. It was not until a few months later that she and her son were able to leave the country.

Other members Alwadaei’s family, including his sister, have also faced interrogations.

When asked how he continues campaigning under these circumstances, Alwadaei told index: “We can only get through this by sticking together and staying strong. It’s important to have a supportive family. The potential for arrest and torture is something they know and have to be willing to sacrifice.”

He added that he is balancing his efforts to get his mother-in-law out of prison while continuing his work in activism. “It’s hard but this is the right thing to do.”

“The oppression or torture aims to do one thing: to break your will because you’re not ready for the consequences,” Alwadaei said. “This is the state they want to leave you in. They want you to be broken and this is why we keep going.”

A life-long struggle

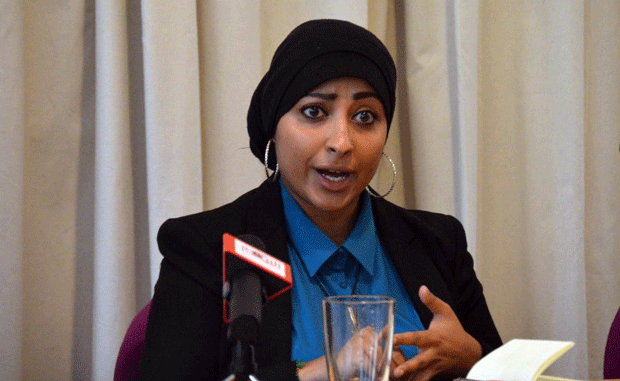

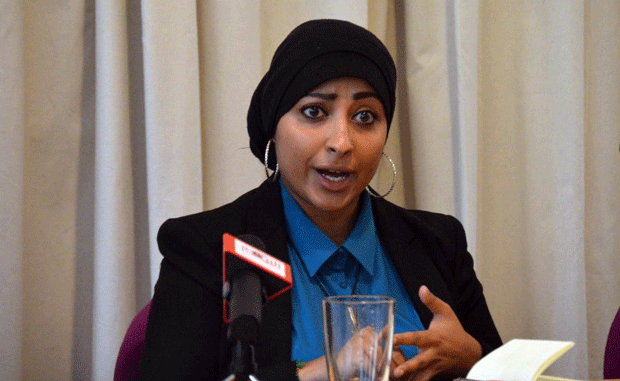

Maryam Al-Khawaja has been preparing for and participating in the struggle for human rights her entire life.

As a young child growing up in Denmark, she and her three sisters attended an English-speaking school, but the Al-Khawaja family knew they were only in the country temporarily. Her mother and father had been exiled for speaking out in Bahrain.

At a very young age, she remembers her parents asking her and her siblings before bed: “What have you done today to make the world a better place?” She told Index that her father wouldn’t help them answer the question because he wanted them to think about how the world could be. She remembers dinner conversations alive with politics and philosophical discussion about whether having false hope or no hope was better.

Around the 7th or 8th grade, Al-Khawaja knew wanted to be like her father when she grew up; she wanted to be an activist.

Maryam Al-Khawaja (Photo: David Coscia for Index on Censorship)

Al-Khawaja was 14 when her family returned to Bahrain in 2001. She recalls thinking her family was ready to take on the challenges and that the people of Bahrain would be ready to fight with them. But that was not the case. The country was tired of conflict and believed that the king’s promised reforms would be implemented. At the same time, activists were not popular among ordinary Bahrainis.

At college she said she was criticised by her classmates for speaking her mind about the state of their country, which caused her to lose interest in her father’s reform work. At the time, she asked him: “Why are you trying to change a situation for people who don’t want to change it for themselves?” His response was simple: “Someday you will understand.”

It wasn’t until 2011 during the Arab Spring protests that she developed a newfound respect for her father and was ashamed of herself for ever doubting him. She admits growing up in Denmark made her think fighting for human rights would be easy. When her father, along with 12 other leaders of the uprising, was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment, she found that a life of campaigning isn’t so effortless.

During our conversation, Al-Khawaja jumped off the phone for a few minutes to take a call from her father. She had not heard from him in over three weeks and said their phone calls are always random and typically short as it is normal for the line to be cut if anything about the Bahrain government or any activist’s work is mentioned.

Until recently, her mother and sisters in Bahrain had not seen her father since February as their requests to visit have continually been denied. Al-Khawaja has not seen her father since 2014 as there are multiple fabricated charges against her that would mean imprisonment if she returned to the country.

Since her father’s imprisonment, Al-Khawaja and her older sister Zainab have been active in the push for human rights and freedom of speech in Bahrain. She says her father has two main characteristics as an activist: a fierce advocate and a fiery speaker. She explained that she and Zainab are the two parts to that whole: Al-Khawaja as the advocate and Zainab as the speaker.

Al-Khawaja said the work of her father and her sister Zainab has been tough for her two younger sisters. One sister had the highest scores in nursing school in Bahrain and graduation seemed to promise a job. But the paperwork from the government granting her access to work never came. She’s been waiting nearly eight years without a job. Al-Khawaja said it’s difficult for her family members when they’re in jail as they have to “take care of us when we cannot take care of ourselves”.

Her mother also felt the effects of the family member’s work when she was fired from her private school teaching job where she was the head of guidance.

A cause for celebrity status never wanted

Adam Rajab realised when he was young that his father Nabeel wasn’t like other dads. “I was so confused ‘why does my father work all day, while other fathers have certain working hours?,’” he told Index.

During a holiday he asked his father to take a break for a day. His father answered: “My colleagues are in prison. I can’t stop my work because they are suffering behind bars.”

In 2006, when Rajab was nine years old, he vividly recalls seeing his father come home bleeding from his head with a swollen and bruised back. “I was shocked and terrified but my father continued protesting like nothing had happened,” he said. “This was terrifying to me but the determination and fearlessness I saw in him really inspired me.”

In 2011 Nabeel Rajab’s work became well known. He appeared on TV and was the first activist to use social media to support the revolution then sweeping Bahrain. “Wherever we went, people would stop him and start taking pictures,” Adam said, adding that the strange situation was a shock to the family. “It started to become difficult because we couldn’t enjoy a private life like we used to.”

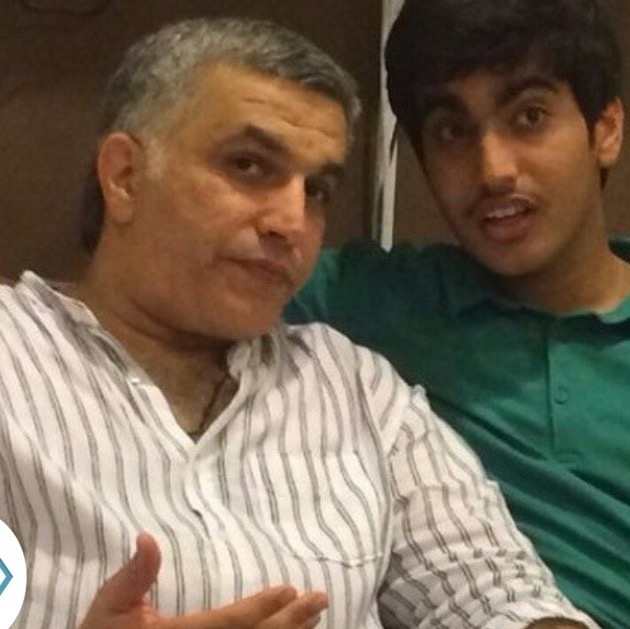

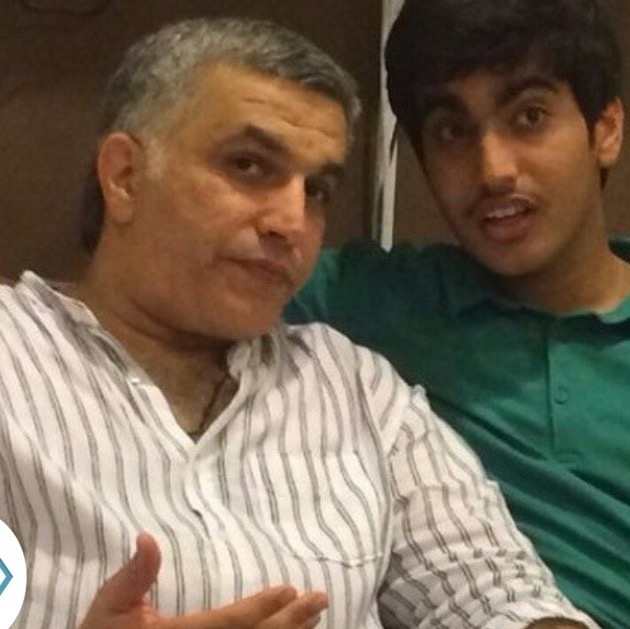

Nabeel Rajab with his son Adam Rajab

As a leader of the movement, Rajab’s father has become a face leaders around the world recognise but do little about. For years he has been in and out of jail. On 10 July 2017 he was sentenced to two years in prison for “broadcasting fake news”.

Although no one in the family has been arrested, his mother was harassed at her government job and then fired. Rajab and his sister have also faced harassment in school.

Rajab and his father have a very close relationship so the imprisonment has not been easy. “I haven’t seen him for more than a year now and he faces more charges which probably means more prison sentences,” Rajab said. “I find it difficult to enjoy anything while he is locked up in a cell and deprived of life, but as he taught me, the spirit is always up.”

Rajab wants his father to free and for them to live like any other ordinary family, but this does not take away from how proud he is or the strength of his belief in his father’s cause.

An open ended sentence

It’s difficult to imagine the emotions these activists and their families go through on a daily basis. A psychologist from the Refer Self Counselling Psychology Practice explained to Index that having a family member with a sentence with a sure release date is one case but when trials or release dates are postponed time and time again as they are in Bahrain, it is much more difficult. “We are rational problem solvers but not good with the unpredictable.”

The psychologist explained the situation in Bahrain is unlike what most with family members behind bars will ever experience. False hope puts an even greater emotional strain on loved ones.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1503052292764-bb1a6c59-5e91-2″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Aug 17 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 46.02 Summer 2017

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Yemeni journalist Abdulaziz Muhammad al-Sabri wears a sling after he was shot by a sniper in 2015

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Yemeni journalist Abdulaziz Muhammad al-Sabri details the dangers of reporting in his country. Interview by Laura Silvia Battaglia”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Abdulaziz Muhammad al-Sabri is smiling, despite everything. But he cannot fail to feel depressed when he sees the photos taken a few months ago, in which he is holding a telephoto lens or setting up a video camera on a tripod: “The Houthis confiscated these from me. They confiscated all my equipment. Even if I wanted to continue working, I wouldn’t be able to.”

Al-Sabri is a Yemeni journalist, filmmaker and cameraman, and a native of Taiz, the city that was briefly the bloodiest frontline in the country’s civil war. He has worked in the worst hotspots, supplying original material to international media like Reuters and Sky News. “I have always liked working in the field,” he said, “and I was really doing good work from the start of the 2011 revolution.”

But since the beginning of the war, the working environment for Yemeni journalists has progressively deteriorated. In the most recent case, veteran journalist Yahia Abdulraqeeb al-Jubaihi faced a trial behind closed doors and was sentenced to death after he published stories critical of Yemen’s Houthi rebels. Many journalists have disappeared or been detained, and media outlets closed, in the past few years.

“The media industry and those who work in Yemen are coming up against a war machine which slams every door in our faces, and which controls all the local and international media bureaus. Attacks and assaults against us have affected 80% of the people employed in these professions, without counting the journalists who have already been killed, and there have been around 160 cases of assaults, attacks and kidnappings. Many journalists have had to leave the country to save their lives. Like my very dear friend Hamdan al-Bukari, who was working for Al-Jazeera in Taiz.”

Al-Sabri wanted to tell his story to Index on Censorship without leaving out details “because there is nothing left for us to do here except to denounce what is going on, even if nobody is listening to us”. He spoke of systematic intimidation by the Houthi militias in his area against journalists in general, and in particular against those who work for the international media: “In Taiz they have even used us as human shields. Many colleagues have been taken to arms depots, which are under attack from the [Saudi-led, government-allied] coalition, so that once the military target has been hit, the coalition can be accused of killing journalists.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”In Taiz they have even used us as human shields” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This sort of intimidation is one of the reasons why researching and reporting on the conflict is very difficult. “In Taiz and in the north, apart from those working for al-Masirah, the Houthis’ TV station, and the pro-Iranian channels, al-Manar and al-Alam, only a few other journalists are able to work from here, and those few, local and international, are putting their necks on the line,” said al-Sabri.

“You’re lucky if you can make it, otherwise you fall victim to a bullet from the militias, attacks, kidnappings. Foreigners are unable even to obtain visas because of the limitations imposed by [Abdrabbuh Mansour] Hadi’s government and the coalition. The official excuse is that the government ‘fears’ for their lives, since if they were kidnapped, imprisoned or died in a coalition bombardment, it would be the Yemeni government’s responsibility.”

Al-Sabri has personal experience of the violence against journalists in Yemen. In December 2015, he was wounded in the shoulder by a sniper who was aiming at his head. On another occasion, he was kidnapped, held at a secret location for 15 days, blindfolded, threatened with death and tortured.

The full article by Laura Silvia Battaglia is available with a print or online subscription.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Award-winning journalist Laura Silvia Battaglia reports regularly from Yemen. Translated by Sue Copeland.

This article is published in full in the Summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Print copies of the magazine are available on Amazon, or you can find information about print or digital subscriptions here. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), and Home (Manchester). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80562″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422014550963″][vc_custom_heading text=”The future of Yemeni journalists” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422014550963|||”][vc_column_text]September 2014

The Yemeni government should not be the ones judging the objectivity of reporting, but there is hope for more freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80569″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422016657007″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalists face increasing threats” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422016657007|||”][vc_column_text]June 2016

Rachael Jolley explains why journalists around the world, especially near the Middle East, are facing increasing threats.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80562″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422014548392″][vc_custom_heading text=”Journalists should ignore technology” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422014548392|||”][vc_column_text]September 2014

Journalists in war zones may need to ignore technology and go back to old ways to avoiding surveillance, says Iona Craig.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”100 Years On” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2017%2F06%2F100-years-on%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the consequences of the 1917 Russian Revolution still affect freedoms today, in Russia and around the world.

With: Andrei Arkhangelsky, BG Muhn, Nina Khrushcheva[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2017/06/100-years-on/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Aug 17 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2017, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”89311″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award-winner Ildar Dadin has returned to activism since his release from prison in February when his conviction was overturned by Russia’s constitutional and supreme courts.

Dadin was sentenced to three years in prison in December 2015 under a 2014 public assembly law. His crime was staging one-man pickets, often holding a billboard, in public. In November 2016, a letter from Dadin to his wife was published, exposing torture he experienced in prison. In April 2017, Dadin was prevented from attending the Index Freedom of Expression Awards in London.

When asked about the international attention his imprisonment received, Dadin expressed that he feels Russian civil society is part of a global society, rather than a totally isolated group. He believes that pressure from civil society both in Russia and abroad were partially responsible for his release. The ultimate goal of his activism shares this global view. He hopes for “justice for all people, not just Russians, humans”.

In June, Dadin was awarded the Boris Nemtsov Prize, which honours individuals who are “particularly committed to fighting for the freedom of expression and helping those who are persecuted on political, racial or religious grounds.” Dadin previously referenced Nemtsov as an example of a Russian opposition leader killed for his activism and beliefs in his Index Awards acceptance speech . Without proper travel documents, Dadin was unable to attend the awards ceremony.

A Russian court ordered the Russian Ministry of Finance to pay Dadin a compensation of 2.2 million rubles for unlawful criminal prosecution in May. He originally demanded five million rubles, and in June filed an appeal to increase the compensation.

Previous prosecution for his activism has not stopped Dadin from continuing to push for freedom of expression in Russia. In June, he read aloud from the Russian constitution on Red Square. He was fined 20,000 rubles ($350) for holding a public gathering without permission.

Moving forward, Index is helping Ildar with his transition to life outside of prison and prioritizing his health.

Additional reporting by Claire Kopsky[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502705474532-50095286-2580-2″ taxonomies=”9013″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Aug 17 | Index in the Press, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”95179″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]This column originally appeared in the Evening Standard.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]”Part of building an open, inclusive environment means fostering a culture in which those with alternative views…feel safe sharing their opinions.” Hear, hear. This is a view that so chimes with my beliefs as a free-speech campaigner that I could have written it myself. In fact, those are the words of Danielle Brown, Google’s vice-president of diversity, integrity and governance, in response to the furore over the so-called Google manifesto — the 10-page document in which Google software engineer James Damore outlined his views on why women don’t reach the top roles in certain jobs, arguing why the company’s diversity pushes were misplaced. Google so cherishes diversity it sacked a man for expressing an opinion it didn’t agree with… Spot a problem here?

In all the furore surrounding Damore’s memo, most of the focus has been on critiquing the views he expressed on the differences between men and women, but far less attention has been paid to the broader point he was trying to make: that unpopular views, views that did not accord with the mainstream ideology in the company, could not be expressed. And that this in turn could lead to a monotheistic culture that is not good for business.

“When it comes to diversity and inclusion, Google’s Left bias has created a politically correct monoculture that maintains its hold by shaming dissenters into silence,” Damore wrote. By sacking him, Google made Damore’s point for him.

Damore expressed a viewpoint that did not accord with the mainstream and he was sacked. I have read plenty of articles arguing he was dismissed not for expressing his opinion but because the expressing of that opinion made colleagues feel unsafe or uncomfortable (more on that later), or justifying the sacking because an employer has the right to discipline employees where their behaviour brings the company into disrepute. But actually, what those who defend Damore’s sacking are really doing is reinforcing something that is increasingly prevalent in our societies: a kind of liberal intolerance.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Ideas are not challenged by silencing them.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]I heard it a lot in the wake of the killings at French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo: “I believe in free speech, but…” and after that “but” came all kinds of things that the supposed defenders of free speech were in favour of censoring because they felt such censorship would better protect marginalised communities. The argument seemed to be that by banning certain kinds of speech we would somehow miraculously eradicate the dangerous, insidious and hateful viewpoints that underlie it.

This “it is OK to censor certain opinions” line is one most clearly articulated in universities — something Damore alluded to in his own manifesto. Views that are considered offensive are dubbed harmful, and speakers are drummed off campus — in some cases physically. In one incident earlier this year, Dr Charles Murray — a political scientist labelled a “white nationalist” for his book linking race and intelligence — was attacked by students after he tried to give a talk at Middlebury College in Vermont.

Ideas are not challenged by silencing them. Indeed, the video of Murray being shouted down by a group of students denying his right to speak demonstrates how an event that could have been an opportune moment to challenge ideas with which the students disagreed simply became an exercise in controlling the narrative. Imagine if the opposite had happened. Imagine if a Black Lives Matter activist had been shut down on campus by a ranting white supremacist mob. There would have been an international uproar.

And that’s the point. Free speech — genuine free speech that tolerates the ideas we find most offensive — must apply equally. It must apply to the ideas we hate as much as to the ideas we champion. What protects Damore’s right to opine that women are “more co-operative and agreeable than men” (Seriously? Has Damore met any actual women?) is also what protects my right to say his views are a laughable load of bollocks. What gives my views the right to be protected and his not?

Those in favour of constraining what others say often do so in the belief that it’s easy to identify, and agree on, good and bad speech. But consider the example of Iranian political activist and human-rights campaigner Maryam Namazie who, in 2015, was repeatedly heckled at an event on blasphemy at Goldsmiths college by members of the Islamic Society and accused of Islamophobia. In one of the great ironies created by the growing “safe space” movement, in which offensive ideas are dubbed so harmful they must be silenced, the Feminist Society at Goldsmiths said it stood in solidarity with the Islamic Society.

This equation of offensive speech with harm lies at the heart of the Google manifesto row, and much of the de facto censorship in operation in companies, online and on campus. Focusing on speech as harm is an easy fix. Don’t like what someone says? Ban them and, lo, we will be safer. (Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is a current good example of this in practice but the UK government’s repeated attempts to deal with “extremist” speech also risk going down this road). This is an easy fix because dealing with the problems underlying the words are so much harder: discrimination based on race, gender, sexuality, religion.

But homing in on speech is a false and dangerous fix. Banning ideas does not make those ideas go away — all too often the banning of an idea gives it more attention — and silencing those with whom we disagree is not the way to the more tolerant and diverse society Google envisages. Far better to let our opponents speak and then challenge them, openly, vocally. And work harder to address the structural problems that persistently marginalise certain groups and so give them a greater voice.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502698304215-3aa8abeb-3e1e-8″ taxonomies=”6323″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Aug 17 | Index in the Press

Journalism is in a delicate state in the world. The time at the turn of the century when it seemed to be secure in freedom, is gone. As June Jodie Ginsberg, the CEO of Index on Censorship, has observed “it does seem as if the world is more authoritarian now.” Read the full article

11 Aug 17 | Awards, News and features, Syria

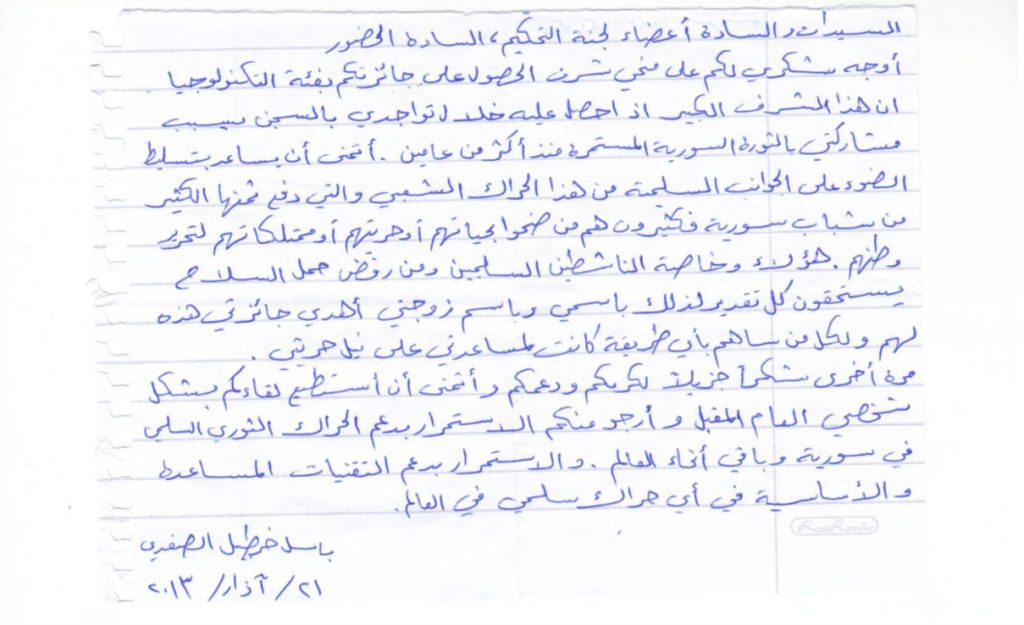

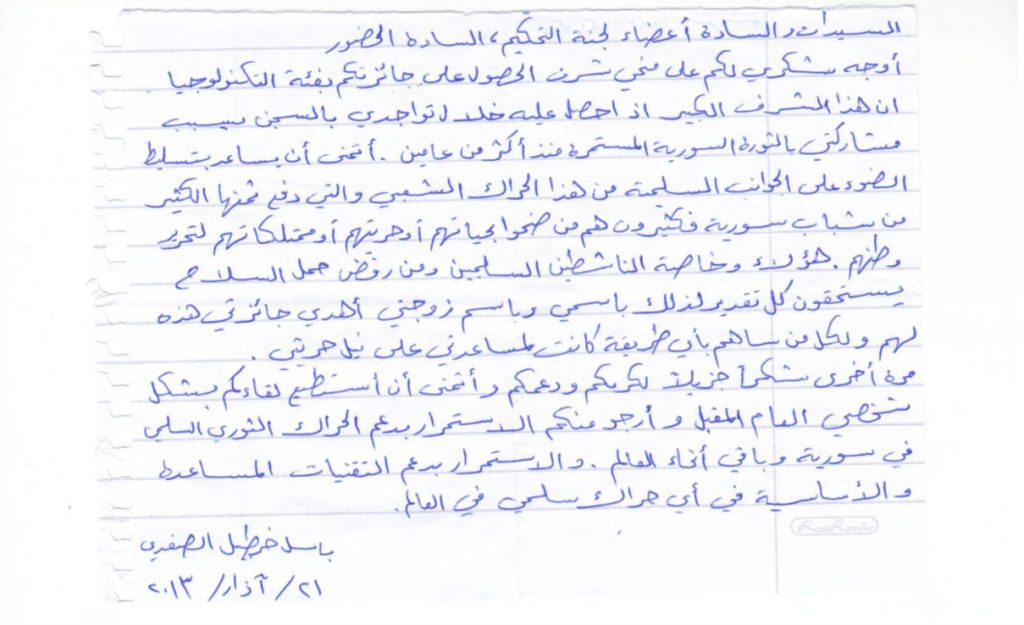

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”95161″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/GUWv8_bOXgg”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]2013 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award-winning Bassel Khartabil, a Syrian-born Palestinian digital activist, worked to build a career in software and web development. Before his arrest in 2012, he used his technical expertise to help advance freedom of speech and access to information in Syria via the internet. His execution by the Syrian government in 2015 was announced by his wife, Noura Ghazi Safadi, on Tuesday 1 August 2017.

The following speech was delivered at the 2013 Freedom of Expression Awards by his friend and colleague Dana Trometer.

Dear Prize Jury Committee Members, Dear Madams and Sirs,

I would like to thank you for this award. I am truly honoured to receive it.

I hope, this great honour, that I receive while I am still in prison for participating in the Syrian Revolution that has been going two years, will shed a light on the nonviolent sides of this popular movement that has claimed the lives of many young Syrian men and women.

Many are those who have lost their possessions, faced imprisonment or sacrificed their souls for freedom in Syria. Those, especially nonviolent activists, who refused to carry arms, deserve all the credit and respect.

Therefore in my name and the name of my wife, I dedicate this award to them, and to all those who are helping me win my freedom back.

I would like to thank you again for your support and for your generosity and I hope I will be able to meet you in person next year, and I urge you to support nonviolent activism and to continue to provide nonviolent movements with the essential technical support in Syria and around the world.

Bassel Khartabil Al Safadi

In prison when he received the 2013 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award, Bassel Khartabil wrote his speech to be delivered by a colleague in the UK.

Bassel Khartabil, winner of the 2013 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award, was in prison when he won the award. His friends accepted the award on his behalf. From left: Jon Phillips, Dana Trometer and then-chair of Index on Censorship Jonathan Dimbleby.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502980043124-10539406-bf4f-4″ taxonomies=”5407″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Aug 17 | Ireland, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”95135″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]There’s considerable disagreement about how to tackle Ireland’s lack of plurality of media ownership. At the same time, there’s a growing pessimism that anything will change in the short term.

“There is no doubt we have a high concentration of media ownership in Ireland…that 45 to 50 percent of weekly newspapers – daily titles, plus weekends – are owned by one media organisation is unusual by any standards. Few other democracies exhibit this degree of concentration,” Dr Roderick Flynn, who focuses on media plurality at Dublin City University told Mapping Media Freedom.

Broadcasting in Ireland is dominated by the semi-state body, RTE. Its radio station, RTE Radio One, holds a clear majority of the most-listened-to shows. Its main TV station, RTE One, is equally dominant. The station also has a very significant presence online, and in addition, owns the Irish language station TG4. RTE received a license fee worth €178.9 million in 2015 but, significantly, the company also competes for advertising on all of its media platforms. However, it posted a €20 million loss last year.

In the commercial sector, the businessman Denis O’Brien plays a very significant role in the broadcasting and publishing landscape. He wholly owns Ireland’s largest commercial news radio stations – Newstalk and Today FM – through his Communicorp group. In addition, the company owns music radio stations such as Spin FM. O’Brien is also the largest shareholder in the Independent News and Media group. INM has full ownership of titles such as the Irish Independent, Sunday Independent, Herald, and Sunday World as well as holding a 50% stake in the Irish Daily Star. It also owns regional newspapers such as The Kerryman and The Sligo Champion. O’Brien’s stake in INM stands at 29.9%.

The National Union of Journalists has campaigned for decades for successive governments to legislate to ensure that media ownership in the country does not remain overly concentrated. However, the NUJ has little optimism that things are about to change. Acting general secretary Seamus Dooley summed-up the mood when he told MMF: “Irish politicians have shown cowardice in tackling issues of media ownership, so we would not be confident of reform in this area.”

This situation has had an impact on Ireland’s reputation. A 2017 report from Reporters Without Borders described media ownership in Ireland as “highly concentrated” and asserted that this posed “a major threat to press freedom.” Ireland has fallen from 9th to 14th place in the RWB standings.

A prominent member of the Irish parliament, Catherine Murphy, who is the co-founder of the Social Democrats party, told MMF: “I think the risks are considerable. The media needs to provide the public with a critical analysis on the major issues. When media ownership is concentrated in too few hands, then there is a danger of ‘group-think’ emerging. A practical example would have been the media coverage in advance of Ireland’s property crash.”

Earlier this year, Murphy introduced a private members bill on media ownership, however it was opposed by the coalition government. She is reserving her judgement on indications by the communications minister, Denis Naughten, that the issue will be tackled.

“I think there were some commitments given, and fine words too, but I would want to see the heads of a bill, or a memo going to cabinet, before I would take those commitments and words seriously. There is a laissez-faire approach often adopted by government. I’m afraid that it could all be lip-service”, Murphy said.

During the debate in parliament, Naughten, said: “I believe a strong and pluralistic media is at the heart of a free and open democracy.” However, he then said that the government would be opposing Murphy’s bill, partly on the basis that he believed that “… the current regime to assess media mergers is working well.”

Naughten also asserted that he was precluded by legislation from taking retrospective action because parliament “… has not provided for powers to retrospectively examine, review or intervene in past media mergers.” He argued that this could raise “significant constitutional issues” because it would be required to be balanced with the right to private property.

Ireland’s capacity to examine media mergers was due to be tested this year when Independent News and Media proposed acquiring Celtic Media – a move which would have increased the number of INM’s regional newspaper titles from 13 to 20. Under cross-media ownership regulations, the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (BAI) was charged with conducting a review, after which the minister for communications would take a decision. However, the €4 million deal was called-off at the last minute – something welcomed by the NUJ which argued that such a merger would have “further undermined media diversity in Ireland.”

Dooley said that the government needs to take a holistic approach, given the plethora of problems facing Irish media – including the flight of advertising to online: “The NUJ has called for a commission on the future of the media in Ireland. This would look at the future of print, broadcasting and digital media. The issue of ownership would form part of the terms of reference. Yes – the industry faces challenges. And the impact of Facebook and Google cannot be understated.”

Other players in the Irish print media include The Irish Times, which is owned and controlled by a trust. Landmark Media controls another national newspaper, The Irish Examiner, as well as a number of regional titles and local radio stations. Landmark is owned by the Crosbie family. The news media giant, News Corp, owns the Irish edition of the Sunday Times, The Irish Sun, and the print-online The Times of Ireland. News Corp also owns several regional radio stations. The Irish Daily Mail is a division of the UK parent company.

The newest broadcasting entrant to the Irish market is the communications giant Liberty Global, which purchased the independent television network TV3. Subsequently, Liberty absorbed the ill-fated station, UTV Ireland, and its financial power has seen TV3 outbid RTE for sports rights.

Given the current situation, the NUJ is very concerned about the capacity of the public to access quality journalism on the major issues of the day. Seamus Dooley told MMF: “Owners seldom directly intervene to influence content. But corporate policies shape news, content and help influence views. So if the emphasis is on maximising profit, at the expense of editorial investment, then that has a significant impact.”

Flynn of DCU has conducted considerable research into this issue. In 2016, he wrote the report Media Pluralism Monitor Ireland and presented the data at a conference in Dublin in 2017 organised by the European Centre for Peace and Media Freedom. He told MMF: “A point that goes slightly under the radar is that as well as owning the two biggest independent radio stations in the country – Newstalk and Today FM – Denis O’Brien’s Communicorp group also owns the Dublin stations 98FM and Spin 103.8. While RTE still accounts for 43% of the County Dublin market as a whole, this drops to 11.2% amongst the 15-24 year olds. By contrast, JNLR listenership figures released in July 2017 suggest that Communicorp-owned stations accounted for more than 52% of the market share in Dublin.”

According to Flynn, the problem is not limited to Dublin. “Newstalk’s so-called ‘rip-and-read’ news service is now used for national and international news bulletins by all regional radio stations in Ireland. That’s another example of the concentration of media ownership here,” he said.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1517486798990-b483150f-f681-9″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

09 Aug 17 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Hamza Yalçın (Photo: Odak magazine)

The arrest of Turkish-Swedish journalist Hamza Yalçın by Spanish authorities is a gross abuse of the Interpol international arrest warrant system and a brazen attempt to stifle press freedom by Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Index on Censorship calls on Spanish authorities to allow Yalçın to return to Sweden.

Yalçın was detained at Barcelona’s El Prat airport on 3 August following an international arrest warrant through Interpol initiated by Turkey.

A day later he was arrested by Spanish police on charges of “insulting the Turkish president” and “terror propaganda” related to an article he wrote for Odak magazine. Yalçın was the chief columnist for Odak and the coordinator for its Training and Solidarity Movement. On 18 March, Turkish prosecutors launched an investigation into Doğan Baran, Odak’s managing editor, and Yalçın for his article entitled The Latest Developments in the Military and the Revolutionary Struggle. Both Baran and Yalçın face charges for “insulting the president” and “denigrating the military.”

“This is a clear abuse of the Interpol system because it is a direct violation of Article 2 of its constitution, which requires respect for fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals. It is extremely concerning that an exiled journalist can be arrested for exercising their right to freedom of expression,” said Hannah Machlin, project manager for Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project monitoring press freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area countries.

The Spanish authorities now have 40 days to decide whether to extradite Yalçın back to Turkey.

“Index demands Spain free Hamza Yalçın and allow him to return to his home in Sweden,” Machlin added.

Yalçın was arrested in 1979 on charges of being linked to the People’s Liberation Party-Front of Turkey (THKP-C) Third Way organization. Odak reported that Yalçın was given two consecutive life sentences by the military junta, which was then in control of the Turkish government, for his “revolutionary activities.” He was granted asylum by Sweden and has lived there since 1984.

Odak magazine, which is campaigning for his release, said in a statement that Yalçın “has been made into a target many times for his articles and values.”

The Council of Europe’s parliamentary assembly published Resolution 2161 in April 2017 on the abuse of the Interpol system. The resolution underlined that “in a number of cases in recent years, however, Interpol and its Red Notice system have been abused by some member States in the pursuit of political objectives, in order to repress freedom of expression.” [/vc_column_text][vc_separator][vc_custom_heading text=”Media freedom is under threat worldwide. Journalists are threatened, jailed and even killed simply for doing their job.” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fcampaigns%2Fpress-regulation%2F|||”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors press freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area nations.

As of 9/8/2017, there were 503 verified incidents associated with Turkey in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship campaigns against laws that stifle journalists’ work. We also publish an award-winning magazine featuring work by and about censored journalists. Support our work today.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502284900540-fbb3abe9-4651-4″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

09 Aug 17 | Index in the Press

Google has fired an employee who wrote a controversial memo opposed to diversity programmes and hiring practices. The company’s chief executive said the “offensive” text advanced “harmful gender stereotypes”. Did Google do the right thing? Read the full article

09 Aug 17 | Awards, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Thailand

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”95084″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Thai journalist Pravit Rojanaphruk, a 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards finalist, has been charged with two counts of sedition for posts made on Facebook. One charge stems from posts in which he criticised a military-drafted constitution — later enacted after a national referendum — and the repeated delays for new elections. The second charge stems from posts that Rojanaphruk wrote addressing the criminal negligence trial of the country’s former prime minister, Yingluck Shinawatra, who was ousted after a military-led coup; the handling of recent floods by the current prime minister, Prayuth Chan-ocha; and a soldier who threatened to confiscate the equipment of a local TV reporter.

“The ongoing judicial harassment of Pravit for performing his professional duties must end. The Thai junta has continuously stifled press freedom and targeted critical voices in the country. We call on the Thai authorities to end its campaign of suppression and drop all charges against Pravit,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said.

Rojanaphruk, a reporter for Bangkok-based news site Khaosod English, must report to police on 18 August. He posted on Twitter that he faces a maximum 14 years in prison if found guilty in both sedition cases.

The Thai junta has targeted Rojanaphruk since seizing power from the country’s democratically elected government in May 2014. [/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”82697″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2016/04/indexawards2016-pravit-rojanaphruk-targeted-speaking-thailands-military-rule/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

On social media Thai journalist Pravit Rojanaphruk’s amused disobedience to his military-assigned “attitude adjusters” serves to make them look outdated and slightly ridiculous. But in reality the ex-senior reporter of The Nation has faced a systematic harassment that would silence most others.

Rojanaphruk is an outspoken critic of Thailand’s lèse majesté law, which bans any criticism of the monarchy, and one of the few voices still speaking against the military rule which has presided over Thailand since 2014.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502267170862-ff1283e8-6776-0″ taxonomies=”164, 8204″][/vc_column][/vc_row]