20 Sep 16 | Events, mobile

Join Index on Censorship and English PEN for a vigil outside the Turkish embassy in support of Ayşe Çelik and others currently persecuted for speaking out in Turkey. This vigil is part of a global campaign launched by the Initiative for Freedom of Expression – Turkey.

Çelik, a teacher, will stand trial beginning on Friday, accused of “promoting terrorist organisation propaganda” after she called in to a popular television entertainment show to plead for more media coverage of abuse and killings of civilians in Diyarbakir, south-east Turkey.

Thirty-one people who co-signed Çelik’s statement will also be tried alongside her. They all face more than seven years in prison if found guilty.

Index on Censorship stands with Ayşe Çelik and will not ignore this breach of her basic right to freedom of expression. We denounce the current crackdown undertaken by authorities in Turkey and call for the immediate and unconditional release of imprisoned writers Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan, Asli Erdogan and Necmiye Alpay.

We will be outside the Turkish embassy from 2pm to 3pm.

Here is the full statement that landed Çelik in court:

Are you aware of what’s going on in Southeast Turkey? Unborn children, mothers, people are being killed here. As a performer, as a human being you should not remain silent to what’s happening. You should say stop. I want to say one more thing. There are miserable people who are glad to hear that children are dying. We, more correctly I, cannot say anything to these people, but shame on you. I’m sorry I want to say one more thing. I’m a teacher and I’m asking all teachers (who fled the area): How will they ever go back to these places? How will they look at those innocent children’s faces and into their eyes? I can’t speak really. The things happening here are reflected so differently on TV screens or on the media. Don’t remain silent. As a human being, have a sensitive approach. See, hear and lend a hand to us. It’s a pity, don’t let those people, those children die; don’t let the mothers cry anymore. I can’t even speak over the sounds of the bombs and bullets. People are struggling with starvation and thirst, babies and children too. Don’t remain silent.

When: Friday 23 September 2pm

Where: 43 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8PA (Map)

19 Sep 16 | Magazine, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

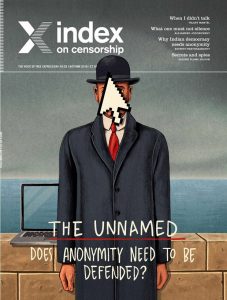

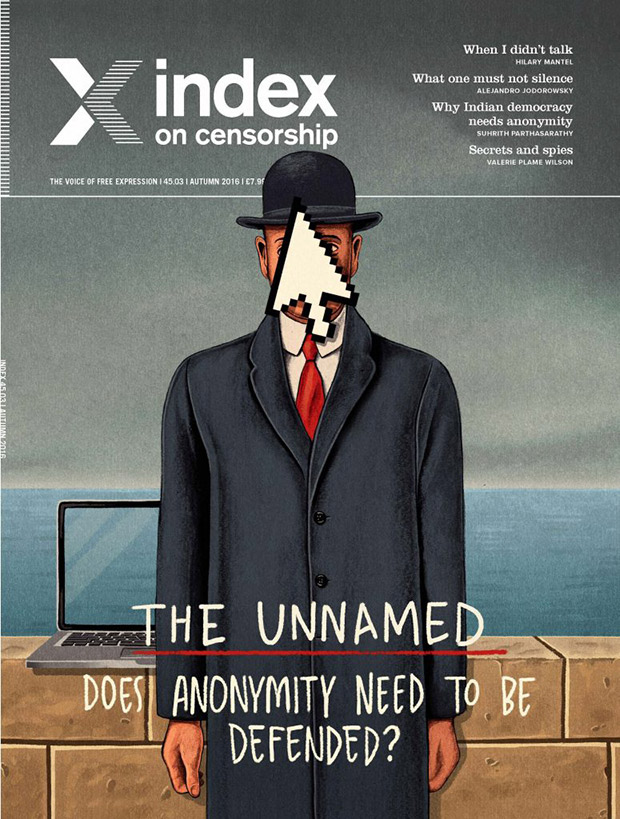

Autumn 2016 magazine cover

Anonymity is out of fashion. There are plenty of critics who want it banned on social media. It’s part of a harmful armoury of abuse, they argue.

Certainly, social media use seems to be doing its best to feed this argument. There are those anonymous trolls who sent vile verbal attacks to writers such as US author Lindy West. She was confronted by someone who actually set up a fake Twitter account under the name of her dead father.

Anonymity has been used in other ways by the unscrupulous. Earlier this year, a free messaging app called Kik was the method two young men used to get in touch with a 13-year-old girl, with whom they made friends online and then invited her to meet. They were later charged with her murder. Participants who use Kik to chat do not have to register their real names or phone numbers, according to a report on the court case in the New York Times, which cited other current cases linked to Kik activity including using it to send child pornography.

So why do we need anonymity? Why does it matter? Why don’t we just ban it or make it illegal if it can be used for all these harmful purposes? Anonymity is an integral part of our freedom of expression. For many people it is a valuable way of allowing them to speak. It protects from danger, and it allows those who wouldn’t be able to speak or write to get the words out.

“If anonymity wasn’t allowed any more, then I wouldn’t use social media,” a 14-year-old told me over the kitchen table a few weeks ago. He uses forums on the website Reddit to have debates about politics and religion, where he wants to express his view “without people underestimating my age”.

Anonymity to this teenager is something that works for him; lets him operate in discussions where he wants to try out his arguments and gain experience in debates. Anonymity means no one judges who he is or his right to join in.

For others, using a fake or pen name adds a different layer of security. Writers for this magazine worry about their personal safety and sometimes ask for their names not to be carried on articles they write. In the current issue, an activist who works helping people find ways around China’s great internet wall is one of our authors who can’t divulge his name because of the work he does.

Throughout history journalists have worked with sources who want to see important information exposed, but do not want their own identity to be made public. Look at the Watergate exposé or the Boston Globe investigation into child sex abuse by priests. Anonymous sources can provide essential evidence that helps keep an investigation on track.

That right, to keep sources private, has been the source of court actions against journalists through the years. And those who choose to work with journalists, often rely on that long held practice.

Pen names, pseudonyms, fake identities have all have been used for admirable and understandable purposes over the centuries: to protect someone’s life; to blow a whistle on a crime; for a woman to get published at a period when only men did so, and on and on. Those who fought for democracy, the right to protest and other rights, often had operate under the wire, out of the searching eyes of those who sought to stop them. Thomas Paine, who wrote the famous pamphlet Common Sense “Addressed to Inhabitants of America”, advocating the independence of the 13 states from Britain, first published his words in 1776 anonymously.

From the early days of Index on Censorship, when writing was being smuggled across borders and out of authoritarian countries, the need for anonymity was paramount.

Over the years it has been argued that anonymity is a vital component in the machinery of freedom of expression. In the USA, the American Civil Liberties Union argues that anonymity is a First Amendment right, given in the Constitution. As far back as 1996, a legal case was taken in Georgia, USA, to restrict users from using pseudonyms on the internet.

Today, in India, the world’s largest democracy, there are discussions about making anonymity unlawful. Our article by lawyer and writer Suhrith Parthasarathy considers why if minister Maneka Gandhi does go ahead with plans to remove anonymity on Twitter it could have ramifications for other forms of writing. As Anja Kovacs of the Internet Democracy Project told Index, “democracy virtually demands anonymity. It’s crucial for both the protection of privacy rights and the right to freedom of expression”.

We must make sure that new systems aimed at tackling crime do not relinquish our right to anonymity. Anonymity matters, let’s remember it has a role to play.

Order your full-colour print copy of our anonymity magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Copies will be available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Carlton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

The full contents of the magazine can be read here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89160″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011400799″][vc_custom_heading text=”Going local” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011400799|||”][vc_column_text]March 2011

If the US’s internet freedom agenda is going to be effective, it must start by supporting grassroots activists on their own terms, says Ivan Sigal.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89073″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422013512242″][vc_custom_heading text=”On the ground” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013512242|||”][vc_column_text]December 2013

Attacked by the government and the populist press alike, political bloggers and Twitter users in Greece struggle to make their voices heard.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89161″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011409641″][vc_custom_heading text=”Meet the trolls” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011409641|||”][vc_column_text]June 2011

Whitney Phillips reports on a loose community of anarchic and anonymous people is testing the limits of free speech on the internet.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The unnamed” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2016 Index on Censorship magazine explores topics on anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world.

With: Valerie Plame Wilson, Ananya Azad, Hilary Mantel[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80570″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2016/11/the-unnamed/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Sep 16 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Does anonymity need to be defended? Contributors include Hilary Mantel, Can Dündar, Valerie Plame Wilson, Julian Baggini, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Maria Stepanova “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2”][vc_column_text]

The latest issue of Index on Censorship explores anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world. The special report looks at the pros and cons of masking identities from the perspective of a variety of players, from online trolls to intelligence agencies, whistleblowers, activists, artists, journalists, bloggers and fixers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”78078″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Former CIA agent Valerie Plame Wilson writes on the damage done when her cover was blown, journalist John Lloyd looks at how terrorist attacks have affected surveillance needs worldwide, Bangladeshi blogger Ananya Azad explains why he was forced into exile after violent attacks on secular writers, philosopher Julian Baggini looks at the power of literary aliases through the ages, Edward Lucas shares The Economist’s perspective on keeping its writers unnamed, John Crace imagines a meeting at Trolls Anonymous, and Caroline Lees looks at how local journalists, or fixers, can be endangered, or even killed, when they are revealed to be working with foreign news companies. There are are also features on how Turkish artists moonlight under pseudonyms to stay safe, how Chinese artists are being forced to exhibit their works in secret, and an interview with Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot.

Outside of the themed report, this issue also has a thoughtful essay by novelist Hilary Mantel, called Blot, Erase, Delete, about the importance of committing to your words, whether you’re a student, an author, or a politician campaigner in the Brexit referendum. Andrey Arkhangelsky looks back at the last 10 years of Russian journalism, in the decade after the murder of investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya. Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov looks at how metaphor has taken over post-Soviet literature and prevented it tackling reality head-on. Plus there is poetry from Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky and Russian writer Maria Stepanova, plus new fiction from Turkey and Egypt, via Kaya Genç and Basma Abdel Aziz.

There is art work from Molly Crabapple, Martin Rowson, Ben Jennings, Rebel Pepper, Eva Bee, Brian John Spencer and Sam Darlow.

You can order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: THE UNNAMED” css=”.vc_custom_1483445324823{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Does anonymity need to be defended?

Anonymity: worth defending, by Rachael Jolley: False names can be used by the unscrupulous but the right to anonymity needs to be defended

Under the wires, by Caroline Lees : A look at local “fixers”, who help foreign correspondents on the ground, can face death threats and accusations of being spies after working for international media

Art attack, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Ai Weiwei and other artists have increased the popularity of Chinese art, but censorship has followed

Naming names, by Suhrith Parthasarathy: India has promised to crack down on online trolls, but the right to anonymity is also threatened

Secrets and spies, by Valerie Plame Wilson: The former CIA officer on why intelligence agents need to operate undercover, and on the damage done when her cover was blown in a Bush administration scandal

Undercover artist, by Jan Fox: Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot explains why his down-and-out murals never carry his real name

A meeting at Trolls Anonymous, by John Crace: A humorous sketch imagining what would happen if vicious online commentators met face to face

Whose name is on the frame? By Kaya Genç: Why artists in Turkey have adopted alter egos to hide their more political and provocative works

Spooks and sceptics, by John Lloyd: After a series of worldwide terrorist attacks, the public must decide what surveillance it is willing to accept

Privacy and encryption, by Bethany Horne: An interview with human rights researcher Jennifer Schulte on how she protects herself in the field

“I have a name”, by Ananya Azad: A Bangladeshi blogger speaks out on why he made his identity known and how this put his life in danger

The smear factor, by Rupert Myers: The power of anonymous allegations to affect democracy, justice and the political system

Stripsearch cartoon, by Martin Rowson: When a whistleblower gets caught …

Signing off, by Julian Baggini: From Kierkegaard to JK Rowling, a look at the history of literary pen names and their impact

The Snowden effect, by Charlie Smith: Three years after Edward Snowden’s mass-surveillance leaks, does the public care how they are watched?

Leave no trace, by Mark Frary: Five ways to increase your privacy when browsing online

Goodbye to the byline, by Edward Lucas: A senior editor at The Economist explains why the publication does not name its writers in print

What’s your emergency? By Jason DaPonte: How online threats can lead to armed police at your door

Yakety yak (don’t hate back), by Sean Vannata: How a social network promising anonymity for users backtracked after being banned on US campuses

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Blot, erase, delete, by Hilary Mantel: How the author found her voice and why all writers should resist the urge to change their past words

Murder in Moscow: Anna’s legacy, by Andrey Arkhangelsky: Ten years after investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya was killed, where is Russian journalism today?

Writing in riddles, by Hamid Ismailov: Too much metaphor has restricted post-Soviet literature

Owners of our own words, by Irene Caselli: Aftermath of a brutal attack on an Argentinian newspaper

Sackings, South Africa and silence, by Natasha Joseph: What is the future for public broadcasting in southern Africa after the sackings of SABC reporters?

“Journalists must not feel alone”, by Can Dündar: An exiled Turkish editor on the need to collaborate internationally so investigations can cross borders

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Bottled-up messages, by Basma Abdel Aziz: A short story from Egypt about a woman feeling trapped. Interview with the author by Charlotte Bailey

Muscovite memories, by Maria Stepanova: A poem inspired by the last decade in Putin’s Russia

Silence is not golden, by Alejandro Jodorowsky: An exclusive translation of the Chilean-French film director’s poem What One Must Not Silence

Write man for the job, by Kaya Genç: A new short story about a failed writer who gets a job policing the words of dissidents in Turkey

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: Europe’s right-to-be-forgotten law pushed to new extremes after a Belgian court rules that individuals can force newspapers to edit archive articles

Index around the world, by

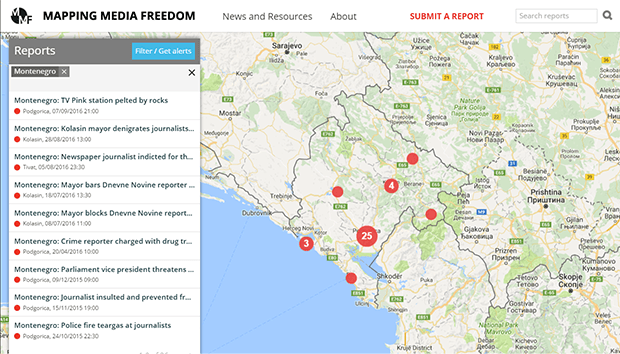

Josie Timms: Rounding up Index’s recent work, from a hip-hop conference to the latest from Mapping Media Freedom

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

What ever happened to Luther Blissett? By Vicky Baker: How Italian activists took the name of an unsuspecting English footballer, and still use it today

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

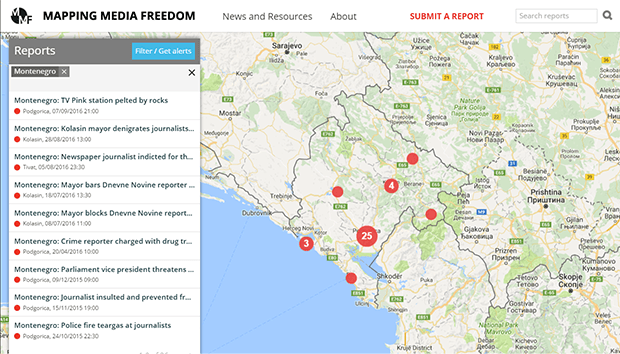

19 Sep 16 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Montenegro, News and features

In the past two months three threats to media freedom involving the mayor of Kolasin, a town in Montenegro, have been reported to Mapping Media Freedom.

Kolasin, which is the centre of a regional municipality of about 10,000 people, has a small media market that includes just one local newspaper named Kolasin and four correspondents working for the national dailies — Pobjeda, Dan, Vijesti and Dnevne Novine. There is no local TV station. The local government is run by a coalition of opposition parties — Democratic Front, the Social Democratic Party of Montenegro (SDP) and the Socialist People’s Party of Montenegro — while the Democratic Party of Socialists is the majority party in the national parliament and it runs the Government.

|

This article is a case study drawn from the issues documented by Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project that monitors threats to press freedom in 42 European and neighbouring countries.

|

|

In two of the cases, the local official, Zeljka Vuksanovic, an opposition politician belonging to SDP, had intentionally not invited Zorica Bulatovic, Kolasin correspondent for the governing party-aligned daily newspaper Dnevne Novine, to press conferences. In the third case, Bulatovic reported that she was verbally harassed.

Bulatovic told MMF that she is being blocked from reporting on Kolasin’s administration as a result of her critical reporting. In a statement to MMF, the mayor said that Bulatovic’s politically motivated reporting is the reason the journalist is not being invited to press conferences. “If you read her articles you will see why I am not communicating with her. You will see that those articles are not articles written by a journalist,” Vuksanovic wrote.

According to CDM, a media outlet owned by the Greek businessman Petros Stathis, who also owns the Dnevne Novine and another daily, Pobjeda, Bulatovic was not invited to an 8 July press session organised by the municipality. The news outlet also reported that Vuksanovic forbid municipality departments from cooperating with or providing information to Bulatovic.

Ten days later, on 18 July, the reporter was the only local journalist not included in a press conference organised after the visit of the national government’s minister for human and minority rights, Suad Numanovic, who called on officials to reverse their decision regarding Bulatovic.

The third incident occurred on 28 August when, in a speech, Vuksanovic said that the local ruling coalition had succeeded in triumphing over “crime, political corruption and media sputum”. Incensed by the speech, the five reporters that were present asked the mayor for an apology and further clarification on her points. The following day, Vuksanovic addressed her reply to four of the journalists, again omitting Bulatovic.

In the response, the mayor said that the term “media sputum” was not directed to the four journalists, but to the “media sputum that is hiding behind journalism as a profession”.

“It’s clear from the incident that the ‘media sputum’ comment was in fact verbal harassment of Zorica Bulatovic,” MMF project officer Hannah Machlin said. “This type of comment only serves to undermine the press as whole.”

Bulatovic told MMF that the negative climate between herself and the mayor has been going on for two years. She said that not only is she facing closed doors at the mayor’s office, but also at the municipal administrations.

The mayor disagrees with Bulatovic’s assertions, saying that the journalist is not barred from attending press conferences. “It is true that I don’t send her invitations for the press conferences, but I have never physically banned her presence at the press center,” Vuksanovic wrote MMF in an email.

Bulatovic maintains that she is barred from entering the press center. She also said that in the five years she has been reporting for Dnevne Novine, she has not had to make any corrections to her articles.

While Bulatovic is facing daily obstacles to her reporting, the four other local journalists are in a slightly better position since they are invited to press conferences. Yet, according to her, all the journalists face a common problem: despite the 2012 freedom of information law local politicians consistently throw up obstacles to documents or sources that would put them in a negative light.

“This whole situation is enormously impacting my work because it’s impossible for me to get an official statement from the local municipality,” Bulatovic said.

(Self)censorship always happens to someone else

Marijana Camovic, a journalist and head of the Trade Union of Media of Montenegro, said that while she was not fully aware of the situation in Kolasin, she did not know of another case where a reporter has been under a constant ban from press conferences. The usual practice for Montenegrin politicians is to publicly denigrate the work of journalists who are putting them and their administrations under scrutiny.

Camovic said the issue journalists in small communities with limited news sources, like Kolasin, most often grapple with is self-censorship.

“I personally think that self-censorship is an even bigger problem than censorship, as in that circumstance journalists know what is expected from them to write,” she said.

In her experience, it is rare for a journalist to be openly censored by their editor. The union recently undertook research, which will be published in October, that amongst other things asked journalists to comment on censorship and self-censorship in Montenegro. Camovic called the preliminary results very interesting.

“Generally, journalists answer that there are self-censorship and censorship in Montenegro. But, when you asked them whether they have personally been censored or succumbed to self-censorship, then only a few of them answer positively. So the conclusion is that there are self-censorship and censorship, but it always happens to someone else, which is paradoxical in itself,” Camovic said.

Her hypothesis is that journalists are probably ashamed to admit that they adjust to the official media policy to keep their jobs. It is not a secret that media outlets are politically engaged, she said.

“They openly support one and criticise the other political option. This is done without consideration of ethics and the role of the media in the democratic society.”

19 Sep 16 | Events

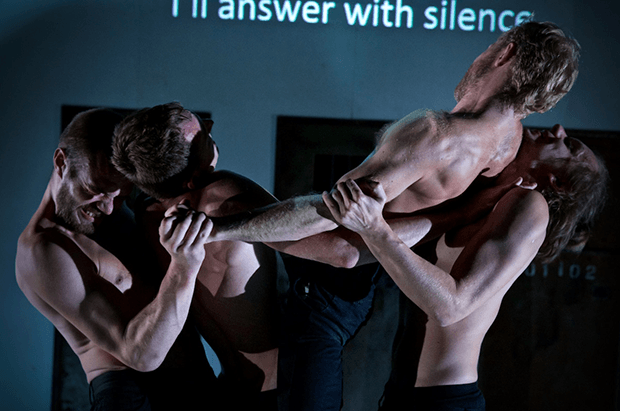

Kiryl Kanstantsinau, Siarhei Kvachonak, Andrei Urazau and Pavel Haradnitski performing in Burning Doors. (Photo by Nicolai Khalezin for Belarus Free Theatre)

Body Politic is Dance Umbrella’s strand of discussions and debates focusing on key cultural issues affecting dance and performance.

How does a climate of censorship affect art? There are different ways of not being allowed to speak. In this discussion, we ask artists how issues of censorship, both public and private, are reflected in their art. How does censorship affect the language of the body? Are there things we cannot say, even when not using language?

This event will be chaired by Julia Farrington, Index on Censorship.

The panel will include Dance Umbrella 2016 (DU16) Festival choreographer Jamila Johnson-Small, Natalia Kaliada, founding co-artistic director of Belarus Free Theatre and Pelin Başaran, an arts curator and producer from Turkey.

This is a Dance Umbrella initiative, presented in partnership with Free Word, Index on Censorship and One Dance UK.

When: 17:15 Wednesday 19 Oct 2016

Where: Free Word Centre, 60 Farringdon Road, London EC1R 3GA (map)

Tickets: £5 from Free Word Centre

16 Sep 16 | Index in the Press

Hilary Mantel has revealed how her childhood was marked by a reluctance to speak, in a provocative essay in which she urges writers that “if you don’t mean your words to breed consequences, don’t write at all”.

Writing in the new issue of Index on Censorship’s magazine, Mantel, who has won the Man Booker prize twice for her historical novels set around the life of Thomas Cromwell, says her muteness was “prolonged … to the point of enquiry: ‘Doesn’t she talk, what’s wrong with her?’”, and that “throughout childhood I felt the attraction of sliding back into muteness”.

Read the full article

16 Sep 16 | Magazine, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

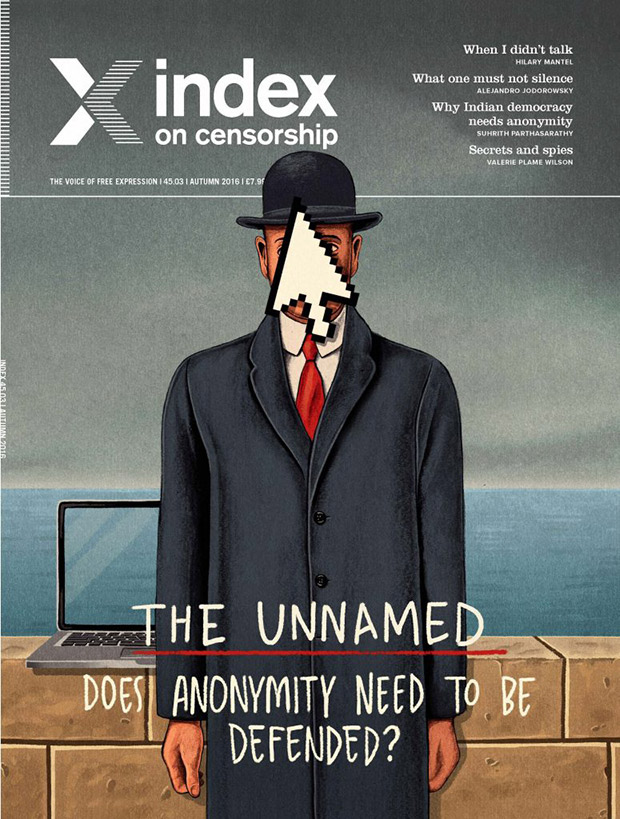

Autumn’s anonymity cover by Ben Jennings

The forthcoming issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world. The special report looks at the pros and cons of masking identities from the perspective of a variety of players, from online trolls to intelligence agencies, whistleblowers, activists, artists, journalists, bloggers and fixers. Contributors include former CIA agent Valerie Plame Wilson, journalist John Lloyd, Bangladeshi blogger Ananya Azad and philosopher Julian Baggini,

Outside of the themed report, this issue also has a thoughtful essay by novelist Hilary Mantel, called Blot, Erase, Delete, illustrated by Molly Crabapple. Andrey Arkhangelsky looks back at the last 10 years of Russian journalism. Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov explores how metaphor has taken over post-Soviet literature and prevented it tackling reality head-on. There is also poetry from Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky and Russian writer Maria Stepanova, plus new fiction from Turkey and Egypt, via Kaya Genç and Basma Abdel Aziz.

You can pre-order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies will be available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Carlton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

16 Sep 16 | Africa, Eritrea, News and features

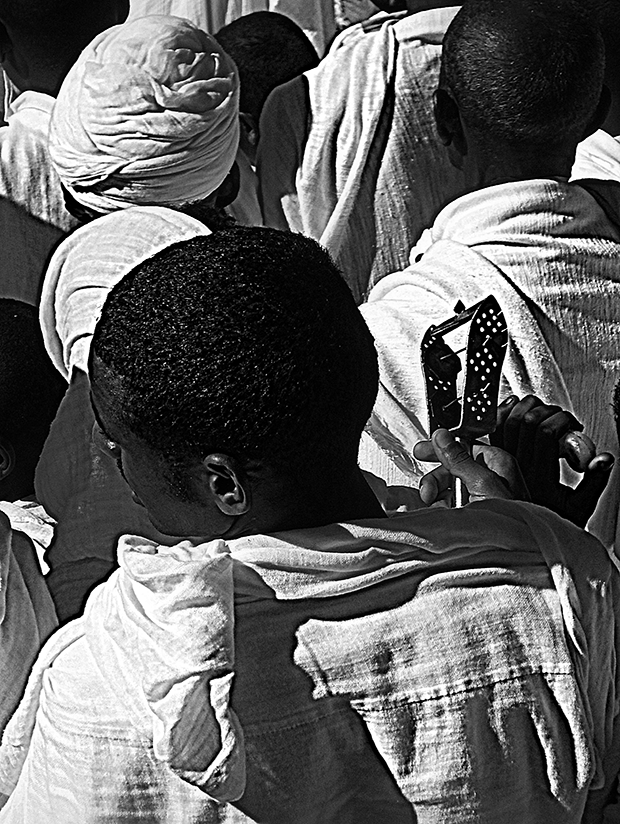

Scenes from Eritrea, photographs by Yonatan Tewelde

It initially sounded like a joke; gradually it got serious and then tragic. A decade and a half later, it is catastrophe.

Fifteen years ago on 18 September, 2001, fellow students of University of Asmara and I were confined in two labour camps, GelAlo and Wi’A, for defying a requirement of unpaid summer work. We were kept in the camps, under harsh, atrocious living conditions and open to the weather that normally reaches 45 C (113 F) for about five weeks. As we were preparing to return home, we learned the government had banned seven private newspapers and imprisoned 11 top government officials.

The day after our homecoming, beaten down and demoralised, I went to meet Amanuel Asrat, chief editor of Zemen newspaper. About 10 days before that, he had received an article, in which I detailed our living conditions, that I had managed to get smuggled out of the prison camp. My piece was published in the last issue of the newspaper.

An atmosphere of fear pervaded Asmara. The environment had changed abruptly from heated and loud political debates to people resigning themselves to whispers and silence.

Unlike our previous meetings when Asrat greeted me with a joke, this time his dejection was obvious.

I do not remember exactly what we talked about, nor do I remember where we met. I assume Asrat must have expressed satisfaction about my safe return (as two students had died in the camp) and perhaps asked about my family. It’s possible we talked about the days before we had been sent to the prison camp. I do not know.

Yet, I remember vividly that we briefly talked about the letter I had sent him from the camp, and him explaining why he had published it anonymously. He didn’t want to incriminate me in its publication. Asrat also assured me that he had destroyed the original letter after publishing it.

What else do I remember from that encounter? Nothing substantial apart from him saying in a resigned tone, “Things are getting worse. It is inevitable we [the journalists] will also follow the political leaders [who had been imprisoned].”

At that point, we went our separate ways, probably hoping to meet some days later.

Before a second meeting with Asrat, I received the news of his and other journalists’ arrests. Even then, no one thought they would be held for more than a few days or weeks.

This is why journalist Dawit Habtemichael showed up at his workplace the next morning — even after security had come to his home the previous day and hadn’t found him. He reasoned that they would arrest him and release him shortly thereafter, a common occurrence at the time. He arrived confidently at his office, prepared to be arrested. He probably felt that fleeing would be an act of betrayal to his colleagues and friends.

Contrary to expectations, both Habtemichael and Asrat have been kept incommunicado in secret prisons with 10 other journalists and 23 political figures for the last 15 years. The Eritrean authorities have never clarified their fates, but some allegedly leaked information by an anonymous whistleblower indicates that only 15 of the total 35 prisoners are alive in the worst living conditions. The journalists who were incarcerated in connection with the press crackdown in 2001 are: Amanuel Asrat, Idris Said Aba’Are, Seyoum Tsehaye, Yousif Mohammed Ali, Said Abdelkadir, Medhanie Haile, Dawit Isaak, Dawit Habtemichael, Matheos Habteab, Fessaha “Joshua” Yohannes, Temesegen Ghebereyesus, and Sahle “Wedi-Itay” Tsegazeab. The leaked source allegedly states only five of the 12 were alive in deteriorating health conditions as of the beginning of this year.

So until the arrested journalists were transferred to an unknown prison outside the capital, many of us – and maybe even those who had been arrested – had high hopes that things would normalise and they would shortly be released from detention. Apart from the architects of repression, nobody guessed that the reign of terror and fear would last for 15 years – and continue to this day.

The culture of fear and hushed whispers gradually pervaded Eritrea until it became the nation’s signature reality. All roads began leading to dead ends. Silence and lack of cooperation became the only means of defiance that would not lead to arrest and imprisonment. The regime’s elimination of all independent media operating in the country conspired with a lack of public forums to effectively zombify Eritreans living inside the country.

Now it has reached a stage where failure to applaud unconditionally all actions taken by the government, no matter how irrational or arbitrary, can be considered as dissidence.

Over the last 15 years Eritreans have been pushed to the edge. Fear has been internalised. Nationals living inside the country are beaten down to docility and respond to orders and requirements without question. The country is plagued with harsh living conditions as a result of shortsighted policies, tattered institutions and a ragged social fabric characterised by mistrust.

Unlike 2001 when I was confident that the journalists would be released after a short time, in January 2015, I celebrated as miraculous the release of Radio Bana journalists after six years in prison without charges. Of course, I had no doubt they were all innocent, and the release of an earlier batch two years before confirmed this fact. Among them was a man who had been imprisoned for four years in place of another man who shared the same first name. In another nonsensical interrogation, related by one of the Radio Bana journalists who were released, authorities showed a print article as evidence of a broadcast allegedly aired by the opposition radio station.

No matter how long the Radio Bana journalists had stayed in prison or the sufferings they had gone through, their release was still big news to celebrate. Any release of political prisoners has been a rare occurrence in Eritrea, which is why many of us called the freed journalists to congratulate them. In a system that follows the perverted logic of “guilty until proven innocent,” it was important to celebrate their freedom because no one can guess the irrational acts the regime repeatedly takes.

With the state media parroting ceaseless propaganda and hate-filled editorials, citizens have mastered a special skill: how to read between the lines. Most Eritreans do not listen to what the president says in his regular, repetitious interviews with the national media. Rather they read his gestures, listen to his tone and scan his appearance to get a feel for the state of the country. Many Eritreans check the media just long enough to determine whether he looks healthy or not.

This accumulation of fear, with a stifled media and ubiquitous censorship, has earned Eritrea the title of “most censored country in the world”, according to Committee to Protect Journalists. It also has placed it as the last country in World Press Freedom Index, as reported by Reporters Without Borders.

More about Eritrea

Letter: Eritrea must free imprisoned journalists

Escape from Eritrea: Ismail Einashe

Scenes from Eritrea, photographs by Yonatan Tewelde

Yonatan Tewelde is an Eritrean photographer and filmmaker who is also working as PEN Eritrea in Exile’s webmaster and graphic designer

16 Sep 16 | Bosnia, Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Italy, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Netherlands, News and features, Serbia

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Members of the Greek far-right Golden Dawn party assaulted a journalist at a protest against the presence of a refugee detention centre on the island of Chios on 14 September.

Editor-in-chief of Astrapari.gr, Ioannis Stevis, was covering the events at the entrance of the camp when a local representative of Golden Dawn, Mattheos Mermigousis, assaulted him and threw his camera on the ground where it broke.

Greek riot police were close by when the assault happened but refused to arrest Mermigkousi despite his request. Stevis has pressed charges against local Golden Dawn representatives.

Ismar Imamovic, an editor at local broadcaster RTV Visoko, was assaulted by a masked individual after he left the TV station on 14 September.

The incident occurred shortly after midnight. As Imamovic told Patria, a few seconds after he had left the building a masked man attacked him from behind. “First he struck me down and then beat me brutally,” Imamovic said.

The incident was reported to the police but so far there is no information regarding the culprits’ identity. Political parties have condemned the attack.

A Dutch-Turkish journalist for the Turkish pro-government newspaper Sabah was arrested in the city of Zaandam while reporting on a police operation on 12 September.

Fatih Ozyar was filming a police raid in an area of Zaandam when he was asked by the police to leave. He told the police that he was a journalist but was arrested with eight other people.

“I was treated roughly by four police officers and brought to a police cell where I was left for 15 hours,” he said. Ozyar was released the following day with a fine for not following police instructions.

The municipality of Amatrice announced on 12 September it plans to sue Charlie Hebdo magazine for a cartoon published about the 24 August earthquake that killed 295 people, Le Figaro reported.

The Amatrice municipal officials announced they were suing for libel.

“This is an unbelievable and senseless macabre insult made to victims of a natural disaster,” the municipality’s lawyer said.

Nedim Sejdinovic, the president of the Independent Journalist Association of Vojvodina, received death threats and threats of violence via Facebook on 12 September.

The threats came after Sejdinovic participated in a roundtable discussion about challenges in modern day Serbia. He compared Serbia in the 90s with the IS today. He also said that he believed Serbia’s ruling party was deeply corrupt and had destroyed society.

The Independent Association of Journalists in Serbia condemned the threats and urged a special prosecutor for cyber crime to identify those who are responsible.

16 Sep 16 | mobile, News and features, Tim Hetherington Fellowship, United Kingdom

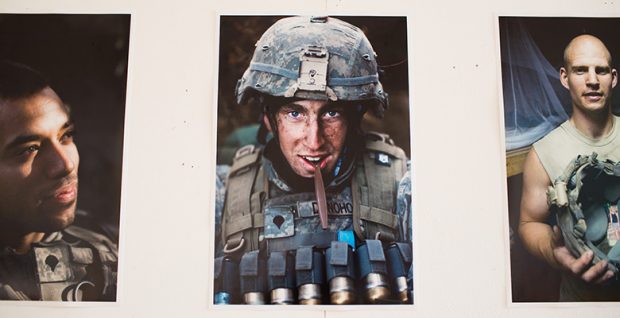

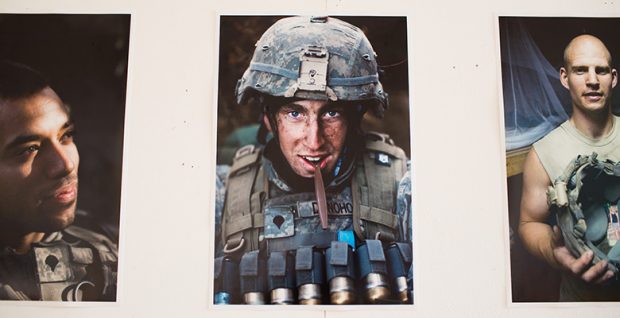

Photo: Liverpool John Moores University

Liverpool John Moores University officially opened its Infidel exhibition, a display of photographs by Tim Hetherington, on Wednesday night. The Liverpool-born photojournalist, who died in Libya under mortar fire in 2011, took the photos during the year he spent embedded with the US Army in Afghanistan’s Korangal Valley while shooting his 2010 Oscar-nominated documentary Restrepo.

Stephen Mayes, a personal friend of Hetherington’s and the director of the Tim Hetherington Trust, spoke at the launch, and highlighted three moments from Hetherington’s short film Diary, which he felt summed up the photographer’s feelings about dividing his time between west London and west Africa. Mayes also recalled a conversation he had with Hetherington around a month before his death, about how photography is great at portraying the “hardware” of war – the guns, the bombs, the carnage – but that Hetherington preferred to work with what he called the “software”, the young men who fight and the people caught in the middle.

The photographs in the Infidel exhibit are a perfect example of what was so impressive about Hetherington’s work. Despite having weathered a year of almost constant combat alongside a platoon of US soldiers, he took striking images that stepped back from the front line. His portraits featured men hugging, relaxing and playing games, highlighting their individual humanity and vulnerability in an environment that treats them as means to an end.

As the new recipient of the Tim Hetherington Fellowship, the result of Index on Censorship’s collaboration with the trust and LJMU (where I graduated in journalism), I’m inspired by the spirit of that work. I’m struck by the bravery and moral fortitude of a man who frequently put himself in harm’s way out of a sense of duty to the people around him. His determination to immerse himself in the lives of his subjects and portray the emotional truth of their experience has reminded me why I always wanted to be a journalist. Journalism is about letting people tell their stories.

Index on Censorship fights for the rights of people to be heard. Hetherington spent his life trying to tell untold stories. It’s an honour to be part of his legacy.

Infidel is open now at the John Lennon Art and Design Building, Duckinfield Street, Liverpool until Friday September 23. Admission is free, 10am to 5pm, Monday to Friday.

15 Sep 16 | Bahrain, Bahrain Letters, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured

Nabeel Rajab, Bahrain Center for Human Rights, – winner of Bindmans Award for Advocacy at the Index Freedom of Expression Awards 2012 with then-Chair of the Index on Censorship board of trustees Jonathan Dimbleby

Rights groups wrote to the governments of 50 states urging them to publicly call for the release of Bahraini human rights defender Nabeel Rajab, who faces up to 15 years’ imprisonment for comments he made on Twitter. Last week, Bahrain brought the new charge of “defaming the state” against him, after an op-ed was published under his name in The New York Times.

The letter from 22 NGOs, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, urges the 50 governments to “speak out on Bahrain’s continued misuse of the judicial system to harass and silence human rights defenders, through charges that violate freedom of expression.”

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy, BIRD: “The Bahraini state is an enemy to the internet and free speech and must be condemned as such by the international community. Bahrain is committing a crime by prosecuting human rights defenders. A strong, clear message can save Nabeel Rajab from a 15 year prison sentence.”

Among those addressed are the governments of France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. While the US State Department called for Nabeel Rajab’s release on 6 September, other governments have not done so. The 50 states addressed in the letter are all previous signatories of statements at the United Nations criticizing Bahrain’s ongoing human rights violations and calling for progress.

The Foreign & Commonwealth Office has

urged “the Bahraini authorities to respect the rights of all its citizens, and call on them to protect the universal rights of freedom of expression.”

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Prince Zeid bin Ra’ad Al-Hussein, used his opening statement at the 33rd Human Rights Council this week to raise concern over Bahrain’s harassing and arresting human rights defenders. He cautioned Bahrain: “The past decade has demonstrated repeatedly and with punishing clarity exactly how disastrous the outcomes can be when a Government attempts to smash the voices of its people, instead of serving them.”

Nabeel Rajab, the President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, has been held in pre-trial detention since 13 June. During this time he has been held largely in solitary confinement, and his health has deteriorated as a result. Since 2011, Nabeel Rajab has faced multiple prosecutions and prison sentences for his vocal activism. He was subjected to a travel ban in 2014 and has been unable to leave the country.

In his current trial, Nabeel Rajab faces charges including “insulting a statutory body”, “insulting a neighbouring country”, and “disseminating false rumours in time of war”. These are in relation to remarks he tweeted and retweeted on Twitter in 2015 relating to torture in Bahrain’s Jaw prison and the role of the Saudi Arabian-led coalition in causing a humanitarian crisis in Yemen.

Most recently, on 5 September Rajab was charged with “deliberate dissemination of false news and spreading tendentious rumours that undermine the prestige of the state and its stature” for an op-ed he wrote to the New York Times. In it, Rajab asked the US authorities: “Is this the kind of ally America wants? The kind that punishes its people for thinking, that prevents its citizens from exercising their basic rights?”

Husain Abdulla, Executive Director, Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain: “This has been another test for Bahrain’s attitude to free expression and it failed it once again. Bahrain has zero respect for free speech. Nabeel Rajab should never have been prosecuted, it is that simple. We want to see the international community take public action against Bahrain’s flagrant disregard of human rights.”

Bahrain was named an Enemy of the Internet by Reporters Without Border in 2014 and is a bottom scorer in Freedom House’s Freedom of the World report. Both RSF and Freedom House are signatories of today’s letter to 50 states.

Nabeel Rajab’s next court session has been set for 6 October, when he is expected to be sentenced.

Background

NGOs and others have been urging action on Nabeel Rajab’s case since he was imprisoned in pre-trial detention in June.

The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy wrote to British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson on 7 September urging public action on Nabeel Rajab.

On 2 September, 34 NGOs wrote a letter to the King of Bahrain calling for Nabeel Rajab’s release.

In August, as part of an initiative organised by Index on Censorship, leading writers wrote a letter to British Prime Minister Theresa May asking the UK government to call on Bahrain, their ally, to release Nabeel Rajab. They included playwright David Hare, author Monica Ali, comedian Shazia Mirza, MP Keir Starmer and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka.

Bahrain: Prominent rights activist charged for New York Times letter

Bahrain delays court date for human rights campaigner for third time

Index award winners and judges call for release of Bahraini campaigner

15 Sep 16 | Tim Hetherington Fellowship

Award-winning photojournalist Tim Hetherington’s ‘Infidel’ exhibition had an emotional opening in Liverpool this week. The exhibition, being held at LJMU’s John Lennon Art and Design building, features moving and intimate images of American soldiers stationed in Afghanistan. Read in full at JMU Journalism.