26 Aug 16 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Ukraine

The armed conflict between the Russian Federation and Ukraine, the occupation of Crimea and Russian support for separatists in Donbas have lead to a large-scale media war, Mapping Media Freedom correspondent Tetiana Pechonchyk writes.

Faced with Russian propaganda, which attempts to stir up hatred, Ukraine imposed a number of restrictions in the media to protect its national security and territorial integrity against its aggressive neighbor. Those restrictions have manifested themselves at different levels and in different ways and touched not only on the Russian media and journalists but also Ukrainian media workers and bloggers who have been accused of being too sympathetic to Russia. In some cases the restrictions have been disproportionate, they have narrowed the space for criticism in Ukraine amid an armed conflict that began in 2014.

The most well-known example is the case of Ruslan Kotsaba, a Ukrainian journalist and blogger, who was arrested in February 2015 for posting a video criticising the country’s military recruitment campaign and called on Ukrainians to boycott it. A month later, on 31 March, Kotsaba was accused of “treason” and obstructing “the legitimate activities of the armed forces of Ukraine”.

After nearly a year and a half in detention — during which Amnesty International named him a “prisoner of conscience” — Kotsaba was acquitted of the charges by the Ivano-Frankivsk court of appeal.

In a second case, Olena Drubych a journalist working for municipally owned Kharkovskie Izvestiya, was fired in March 2016 for republishing material from the Russian website Expert Online, which reported “the Russians celebrated the second anniversary of Crimea returning to the Russian Federation”.

Two reports to MMF involved Russian TV news crews, who tried to work in Ukraine covering events.

In September 2015, Katerina Voronina, a journalist for Russian TV channel NTV was detained along with her driver by representatives of the Right Sector, a far-right Ukrainian nationalist political party, near the administrative border between occupied Crimea. NTV said that the journalist was reporting about a blockade on goods going into Crimea, and was on Ukrainian territory legally. According to the Right Sector website, Voronina, who was questioned for three hours, was filming Ukrainian soldiers. Voronina was then transferred to the Ukrainian State Security Service where she was interrogated for six more hours before being released the following morning.

In April 2016 a film crew from Russian TV channel Mir-24 was denied entry to Ukraine at the Belarusian border by Vystupovychi crossing point border guards. The journalists were planning to visit the abandoned city of Pripyat to report on the anniversary of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. According to border guards, the four correspondents, who were Belarusian citizens, did not have any permits or other documents confirming the objective of their visit.

As Index on Censorship reported in May, the Ukrainian website Myrotvorets, which publishes the personal data of those it believes to support separatism in eastern Ukraine, posted the identities of over 4,000 journalists accredited by the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic. Among those named were correspondents working for the BBC, Reuters, AFP, The Independent, Ceska televize, CNN, Al Jazeera, Liberation, ITAR-Tass and RT. Following the release, the site was criticised and announced it was shutting down, but was back online by 19 May.

Ukrainian authorities launched a criminal investigation but observers have little hope of an objective investigation. The website is openly supported by Ukraine’s interior minister, Arsen Avakov and his advisor MP Anton Herashchenko.

Following the initial post on 7 May, Myrotvorets released a second, larger list on 20 May, which contained 5,412 names including 2,082 Russian and 1,816 international journalists. The site has subsequently registered with Ukrainian authorities as a media outlet.

In 2016, Ukraine’s ranking in Reporters Without Borders press freedom index climbed 22 places to 107th out of 180 countries. According to Freedom House’s world press freedom index, Ukraine is a partially free country, up 11 places over 2015.

This article was updated on 2 September 2016 to provide context and clarification to the nature of the media environment between Russia and Ukraine.

26 Aug 16 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Russia, Ukraine

The conflict over Crimea and the fighting in eastern Ukraine has resulted in a media war, which has left both Russian and Ukrainian journalists struggling to report accurately on the situation, writes Mapping Media Freedom correspondent Andrey Kalikh.

In Russia, the partisan media environment has been driven by state-backed broadcasters. Federally financed TV channels — Russia 1 and RT — toe the government line on events in eastern Ukraine and Crimea. In 2015, the government boosted its funding of media to 72 billion rubles ($1.2 billion).

Mapping Media Freedom is monitoring the situation with Ukrainian media and journalists working in Russia. These are some of the cases filed by MMF Russian correspondents.

Reporting teams working for Ukrainian television outlets were barred from attending the March 2016 trial of Nadezhda Savchenko, a pilot captured by pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine and handed over to Russian military forces. Savchenko was accused of having directed artillery fire that killed two Russian journalists.

Former Los Angeles Times correspondent Sergei Loiko, a Russian, has been repeatedly harassed in Moscow, where he is based, following the publication of articles on the conflict and his book The Airport, a novel set amid the battle for Donetsk airport in eastern Ukraine. In October 2015 he received a threatening phone call, followed in April 2016 by an incident during which four unknown perpetrators approached him as he was entering independent TV Dozhd’s studio to participate in a live programme.

Some journalists have been barred from entering Russia altogether. In one case, Sergei Supinsky, an AFP photographer based in Ukraine, was stopped from traveling to Moscow from Minsk. Supinsky was told he could not board his flight. No reason was given for the ban.

Russian journalists and activists have also become targets for pressure if they are perceived as supporting Ukraine or objecting to Russian involvement in the conflict.

In April 2016, Mikhail Afanasyev, an independent Novaya Gazeta correspondent based in the Republic of Khakassia posted a photo on Facebook of Kiev’s Maidan Square, where he had recently visited. He was immediately targeted with threats and insults by people referring to themselves as “patriots”.

In December 2015, a blogger from the Siberian city of Tomsk received a five-year sentence for “extremist” videos published on his YouTube page. In one of his videos, later removed, Vadim Tyumentsev referred to refugees from eastern Ukraine “who come and stay in Tomsk, although there are enough other problems in the city”. He accused officials of providing more help to the newcomers than the local population.

This article was updated on 6 September 2016 to provide more context and clarification.

24 Aug 16 | mobile, News and features, Youth Board

Index recently appointed a new youth advisory board cohort. The eight young students and professionals, from countries including Hungary, Germany, India and the US, will hold their seats on the board until December.

Each month, board members meet online to discuss freedom of expression issues occurring around the world and complete an assignment that grows from that discussion. For their first task the board were asked to write a short bio and take a photo of themselves holding a quote that reflects their belief in free speech.

Sophia Smith-Galer

I’m half English, half Italian, and was born and raised in London. I have just graduated from Durham University with a degree in Spanish and Arabic and will be studying for a Master’s in broadcast journalism at City University next year.

I have just returned from a trip to New York after winning a multilingual world essay prize which included speaking at the United Nations’ General Assembly. I was in the group of Arabic language winners and our speeches were about tackling climate change, which is one of the UN’s sustainable development goals for 2030. Now that I am embarking on a career in journalism I’m looking forward to continue supporting these goals in my work.

Freedom of expression is particularly important to me as several countries that speak both of the languages I have dedicated years of study to continue to be plagued by tyrants and censors. I’m particularly interested addressing censorship in Latin America and the Middle East, especially with regard to the arts, as I’m also a classical singer and keen art historian.

Shruti Venkatraman

Originally from Mumbai, I am currently a first year undergraduate studying law at the University of Edinburgh. As a law student, I am interested in advocacy in general, but I am particularly interested in advocating for fundamental human rights.

In today’s socio-political context, the phrase “freedom of expression” has gained importance and expanded in its meaning from it’s original intent to prevent minority persecution. Having lived in India and South Africa, I was able to grasp the importance of free speech in the context of regional history, and I learnt how human rights appeals have had local and global impacts and are inherently tied with social development. Index on Censorship’s admirable work to promote and defend freedom of expression highlights how important this cause is in our quest for social progress, justice and equality and how repression of these rights result in societal backwardness.

Niharika Pandit

I am currently a master’s candidate at the Centre for Gender Studies at SOAS, University of London with South Asia as my focus area of gender research. I became interested in issues of censorship during my undergraduate studies in mass media with a specialisation in journalism from Bombay.

As a journalist and an active social media user in India, I was witness to numerous instances of online abuse, trolling and silencing of women politicians, journalists and activists who voiced opinions on political and social issues. As a response to the barrage of abuse in the online space, otherwise a liberating space to hear diversified opinions, I wrote a piece on Twitter trolls in India and the use of sexist abuse as a tool to muzzle women for Index on Censorship’s Young Writers’ Programme.

Within censorship, I am particularly interested in working on the intersections of social media, gender along with looking at censorship in militarised zones and its growing legitimacy in contemporary political ethos as part of my research.

Layli Foroudi

It was studying literary works from the Soviet period during my undergraduate degree that highlighted the issue of censorship for me initially. Clearly this issue has outlived (and predates) the Soviet Union and is still of pressing concern in Russia today and globally. After graduating, I worked as a journalist on issues of freedom of expression and belief in Iran, and then in Russia at the Moscow Times. By pushing a state-sponsored version of the truth and punishing those at variance with it, these countries and others marginalise people and stifle innovation and creativity.

Freedom of expression and public debate underpin what society consists of and being denied this freedom is being denied the right to participation in society, as Hannah Arendt wrote: the polis is “the organisation of people as it arises out of acting and speaking together”. Historically, many have been denied the right to “act and speak”, based on ethnicity, gender, belief, immigration status, etc, and continue to be. I am interested in encouraging a diversity voices in the public sphere, something I have enjoyed exploring more this past year while undertaking an MPhil in race, ethnicity, and conflict at Trinity College Dublin and as a member of the youth advisory board since January.

Ian Morse

I’m a student and journalist at Lafayette College in the US, but I have studied in Germany, Turkey and the UK. I really started studying news media when I lived in Turkey 18 months ago, because even then (much more so now) journalists and bloggers had a very tough time gathering and publishing good information. Since then, I’ve been a journalist in Turkey, the UK and Greece. I study history and mathematics-economics, but almost every project I do is focused on news media.

I’ve encountered freedom of expression violations in many fashions, from student pressures against speakers to petty government retaliation to Twitter blocking. There is quite a bit of nuance that is overlooked in many cases, but that nuance is needed to understand where the line needs to be drawn. Words have a lot of power in society – but it is often difficult to get the truth out when lies are louder or gags are stronger. I hope with Index that we can find ways to fix this.

Anna Gumbau

I am a journalist living between Barcelona and Brussels. I am passionate about youth work, having volunteered for five years as member of AEGEE-Europe / European Students’ Forum, including a year as member of its international board. I have taken part in, and often led projects, run by students for other students all over Europe, on topics such as pluralism of media, election observation and media literacy. I am also involved in the field of internet governance, participating in the last two editions of the EuroDIG and joining the Youth Observatory of the Internet Society.

As a young media-maker who grew up listening to the stories of censorship in the times of the Spanish dictatorship, I believe strongly in free speech, a free press and media pluralism as essential pillars for democracy. I am fascinated by the power of words and freedom of expression to empower citizens and stand up to what they believe in. I also envision free media as a crucial element for better informed societies and, in extension, for more responsible individual citizens to participate in the public space.

Constantin Eckner

I am originally from Germany. I graduated from University of St Andrews with a master’s degree in modern history. Currently, I am a Ph.D. candidate specialising in human rights, asylum policy and the history of migration. Moreover, I have worked as a writer and journalist since I was 17 years old, covering a variety of topics over the years. Longer stays in cities like Budapest and Istanbul have raised my awareness for pressures exerted upon freedom of expression.

In a perfect world journalists, as well as every citizen, would live without fear of state censorship and potentially facing repercussions for the words they write or speak, for the pictures they draw, for the photos they shoot or for music they play.

Freedom of expression and access to information are cornerstones of an enlightened society. Unfortunately, in 2016 the world is still challenged by undemocratic regimes and powers that intend to quash people, which is an oppressive situation that has to change. It is up to us to help those who cannot raise their voice fearlessly.

Fruzsina Katona

Fruzsina Katona

I was born and raised in Hungary, although I spent my pre-university years in a small town in eastern Hungary. Today I am a freelance journalist.

I always knew I wanted to be a journalist, since I was always interested in literally everything that surrounded me. The urge to publish became stronger at the age of 17, after I returned from Japan, where I spent a school year. That one year made me realise, that my home country is really far from the image I had of it. And the only way I can fight against corruption, abuses and narrow-mindedness – apart from voting – is to educate and inform the public. I took an internship at Hungary’s leading investigative journalism center, and 2015 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression award-winner, Atlatszo.hu. I have worked for them as a freelancer ever since, and I enjoy my work pretty much.

I recently received a graduate degree in communication and media studies, and supplemented my “official” studies with training, workshops and conferences across Europe.

In the future I would like to be a post-conflict reporter or a human rights journalist, specialising in freedom of expression and the press.

23 Aug 16 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Media Freedom, Statements

Index on Censorship welcomes the delay in the Royal Charter recognition of Impress by the Press Regulation Panel and hopes it provides an opportunity for further consultation. We are extremely concerned that recognition of Impress has the potential to introduce punitive measures for small publishers and to stifle investigative journalism. We are also concerned that about the transparency of its funding. These are factors that threaten freedom of the press.

We hope the decision today gives an opportunity for a rethink.

Index remains concerned that, aside from the Royal Charter, other elements of legislation introduced in the wake of the Leveson Report represent a threat to media freedom. One of the most worrying of these is Section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013, which sets out that an organisation which does not join a recognised regulator but falls under its remit (through being considered a “relevant publisher”) will potentially become subject to exemplary damages should they end up in court, and could also be forced to pay the costs of their opponents.

|

Such measures could be especially punitive for small publishers and news organisations with limited financial means.

|

|

There are two principles here that threaten a free press. Firstly, that in effect joining a regulator becomes less than voluntary if you have the threat of punitive damages hanging over your head. Secondly, that those who do not join and therefore feel under threat of exemplary damages will skirt away from controversial subjects and investigative journalism, and opt instead for “safe” stories.

Such measures could be especially punitive for small publishers and news organisations with limited financial means. This has a damaging effect on free expression. Supporters of this aspect of the act argue that exemplary damages would only apply to “reckless” action by journalists, but it is possible that a court could find that a breach of Article 8 rights to privacy and reputation was by definition “reckless” even when a journalist was pursuing an investigative news story in the public interest.”

Impress said in January it would accept donations of £3.8 million to cover the first four years of expenditure, which have been reported as coming almost exclusively from The Alexander Mosley Charitable Trust. The organisation’s own website provides only scant information about its current funding.

Although Impress has said it would not “be beholden to anyone” and that a charity would act as “buffer” between any donor from which it receives funds, the idea that a single wealthy individual should control the purse strings for a supposedly independent regulator should strike fear into the hearts of those who believe in a free press.

Index, a small publisher since 1972, has not signed up to a regulator.

21 October 2016: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that section 42 (3) of the Crime and Courts Act sets out that an organisation under its remit could be subject to damages if it does not join a recognised regulator.

23 Aug 16 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

In an extract from her new book, Turkey: the Insane and the Melancholy, journalist and author Ece Temelkuran discusses the role of the Turkish ministry of culture in censoring theatre productions. Temelkuran will be speaking at Waterstones Trafalgar Square on 20 Sept.

In an extract from her new book, Turkey: the Insane and the Melancholy, journalist and author Ece Temelkuran discusses the role of the Turkish ministry of culture in censoring theatre productions. Temelkuran will be speaking at Waterstones Trafalgar Square on 20 Sept.

In 2013, the Ministry of Culture began to evaluate its subsidies to private theatres under the criterion of being “suitable with regard to public decency”. This enforcement arose as part of the Turkey Art Association (TÜSAK), which was put forward in a bill advocating the audition and support of art associations affiliated with the state. In this way, the legal foundation for state-imposed censorship was laid.

For the evaluation of private theatre companies’ grant requests to the Ministry of Culture, submission of the play’s script was made obligatory. Shakespeare’s Macbeth was removed from the State Theatre repertoire in 2014.

In December 2014, Sevket Demirkaya, who had previously held positions such as wrestling referee and municipal police chief, was appointed Director of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Theatre Company. In 2013, the Ministry of Culture cut off its funding to the company of Genco Erkal, one of the most acclaimed stage personalities in Turkey, for supporting the Gezi protests. The Directorate General of State Opera and Ballet prohibited the wearing of certain garments, including leggings, in October 2014.

Theatre wasn’t the only thing Erdogan had a beef with, naturally. He was also passionate about sculpture. On 8 January 2011, during election preparations in Kars – a place the whole world is familiar with thanks to Orhan Pamuk’s novel Snow – he was once again yelling, “Freak show!”

The freak show in question was an enormous statue. The mayor, a member of his own party, was having a peace statue built in the city bordering Armenia, a statue that could be seen from Erivan. The work, by one of Turkey’s most renowned sculptors, Mehmet Aksoy, had just been completed when it turned out that it didn’t suit Erdogan’s tastes. A few months after Erdogan appraised the sculpture as a “freak show”, it was demolished in spite of every court ruling, and at quite a high cost. The worst part about it all was the cry of “the people” as they set about its destruction:

“Allahu akbar!”

I suppose that the intellectuals who were irked when I suggested that sometimes Turkey was like Afghanistan with a nicer shop window, who thought it “elitist and Jacobin”, probably shared my apprehensions on the day they witnessed that savage and wanton destruction.

Erdogan was also interested in music. That was why the work of Fazıl Say, a world-renowned composer and pianist who was critical of the AKP administration, was immediately removed from the repertoire of the Presidential Symphony Orchestra.

Perhaps the eeriest of these persecutions over the years came in December 2011, from the Minister of Internal Affairs. The Minister said: “The backyard of terrorism, walking around the back, and by backyard this could be Istanbul, could be Izmir, Bursa, Vienna, Germany, London, wherever – it could be a podium at the university, an association, a non-governmental organisation … They look like they’re just singing but they say something to the audience in between three songs, squeeze in a few lovely words. Whatever you take from it, however you understand it. They’re making art on that stage. What can you do? We are not against art, but we have to weed these out with the meticulousness of a surgeon.”

I wish the best of luck to the translator who has to translate these words. I hope readers, too, will manage to keep their wits intact after so much of the government’s poor self-expression.

In the wake of these declarations that signalled a new onslaught of custody and persecution, artists came up with a parody petition:

“Ban art! Put art within the scope of terrorist activity!”

This is an extract from Turkey: the Insane and the Melancholy (Zed Books, 2016) by Ece Temelkuran, which is available now.

Ece Temelkuran will be participating in two upcoming events:

15 Sep: The State of Turkey with Kaya Genç, Ece Temelkuran and Daniel Trilling

Join Index on Censorship magazine’s contributing editor Kaya Genç and fellow Turkish writer Ece Temelkuran for a discussion about the state of Turkey in the aftermath of the failed military coup.

20 Sep: Author Ece Temelkuran on the struggles that have shaped Turkey

Join Index on Censorship’s CEO Jodie Ginsberg as she presents an evening with award-winning journalist and novelist Ece Temelkuran to discuss her latest book Turkey: The Insane and the Melancholy.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

22 Aug 16 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

The awards were presented at a ceremony on Thursday 18 August. (Photo: TGC)

The Journalists Association of Turkey (TGC) on Thursday gave a 2016 Press Freedom Award to a coalition of international organisations, including Index on Censorship, that have worked in concert since last year to support journalists in the country and fight an ongoing deterioration in the state of press freedom.

“Press freedom cannot be taken for granted in any country and requires us to be constantly vigilant. As the post-coup crackdown continues, Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom is registering threats to the media, as well as publishing work from censored journalists, to help bring international attention to the issues. Index is grateful to be recognised for its work on behalf of the journalists of Turkey,” Rachael Jolley, deputy chief executive of Index on Censorship said.

The TGC award recognised the group of press freedom and free expression defenders, which came together as pressure on media increased ahead of the country’s second parliamentary election in 2015, for its collective efforts to bring awareness of press freedom violations in Turkey to the world at large and for supporting journalists of Turkey.

The group was assembled by the International Press Institute, which organised a press freedom mission to Turkey in October 2015.

IPI Executive Board Member Kadri Gürsel, chair of IPI’s Turkey National Committee, accepted the award on behalf of coalition members.

Noting the importance of international solidarity in support of Turkey’s journalists, he said that collective action is increasingly key, as pressure on independent media continues to increase under emergency rule declared in the wake of the failed July 15 coup.

The full text of Gürsel’s remarks appear below.

Honourable Chair,

Esteemed Jury members,

Fellow members of Journalists Association of Turkey,

Dear Guests,

Last year, Turkey provoked the creation of something that was the first of its kind in the world.

Almost all international press freedom organisations came together in order to form a coalition to defend the right of journalists in this country to perform their profession freely; a reaction to the political power having increased its repression of the freedom of the press to unprecedented levels in between the two elections.

The highly representative joint emergency press freedom mission of eight international organisations to Turkey on 19 to 21 October 2015 was the first of its kind in the world.

The mission was comprised of international and local representatives from the International Press Institute (IPI), the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Reporters Without Borders (RSF), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), Index on Censorship, ARTICLE 19 and the Ethical Journalism Network.

IPI’s Turkish National Committee and the Union of Journalists of Turkey, a member of the EFJ, endorsed the mission.

Showing solidarity with journalists in Turkey and underlining the fact in Turkey and abroad that growing pressure on independent media would jeopardise free and fair elections in the country – and of course demanding an immediate end to this pressure – were among the objectives of the mission.

The mission met with representatives of 20 media outlets in Istanbul and Ankara. It met with the representatives of opposition parties. It was impossible to get an appointment from the ruling party and from the office of President Erdogan.

The facts collected on the state of the freedom of the press in Turkey were shared with the world in a mission report published on Oct. 31, 2015. Suggestions were also made to make the situation better.

Despite its ad-hoc character, the coalition of international press freedom organisations for Turkey continued its activities with the participation of additional organisations.

The coalition coordinated the call of 50 leading editors around the world who on Oct. 30, 2015 urged President Erdogan to protect press freedom in Turkey.

It made a joint statement for the release of Cumhuriyet journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül, on Dec. 1, 2015.

The coalition made a joint statement to support a mission by RSF to Istanbul with the same purpose.

Representatives of organisations forming the coalition on Jan. 26, 2016 repeated their call for the release of Can Dündar and Erdem Gül at the gates of Silivri prison in Istanbul where the two journalists were held.

The coalition called on Turkey to drop all charges against the Cumhuriyet journalists on March 24, a day before their politically motivated trial.

Coalition members have also been active in submitting alerts to the Council of Europe’s platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists.

I’m standing here today on behalf of the coalition of international press freedom organisations for Turkey to receive this year’s Press Freedom Award of the Journalists Association of Turkey on the category of Institutions, given to the coalition.

On this occasion, I would like to mention names of member organisations of the coalition:

ARTICLE 19

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

The Ethical Journalism Network (EJN)

The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

Index on Censorship

PEN International

The International Press Institute (IPI)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

The World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA)

On behalf of the member organisations, I extend our sincerest gratitude and thanks to the Journalists Association of Turkey for their decision to grant this year’s press freedom award to the coalition.

This award is very meaningful for us because it shows that the international solidarity made for the freedom and future of journalism is fairly evaluated and appreciated.

As facts have shown, the international solidarity of journalists has always been effective and a deterrent to repressive regimes that put media under pressure in order to prevent the public from being informed freely and objectively.

International solidarity is becoming more important these days; the repression of journalists and the media is gaining a destructive character with the unlawfulness of the emergency rule, insofar as the failed coup of July 15 has been used as a pretext for its implementation.

In consciousness of this fact, we are very thankful to the honourable jury members for granting us this award.

Full details of the awards are available are here.

Index will be exploring the situation in Turkey in a series of upcoming events:

12 Sept: Turkey beyond the headlines

Acclaimed writer Kaya Genç will talk to Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine, about his forthcoming book Under the Shadow: Rage and Revolution in Modern Turkey.

15 Sept: The State of Turkey with Kaya Genç, Ece Temelkuran and Daniel Trilling

Join Index on Censorship magazine’s contributing editor Kaya Genç and fellow Turkish writer Ece Temelkuran for a discussion about the state of Turkey in the aftermath of the failed military coup.

20 Sept: Author Ece Temelkuran on the struggles that have shaped Turkey

Join Index on Censorship’s CEO Jodie Ginsberg as she presents an evening with award-winning journalist and novelist Ece Temelkuran to discuss her latest book Turkey: The Insane and the Melancholy.

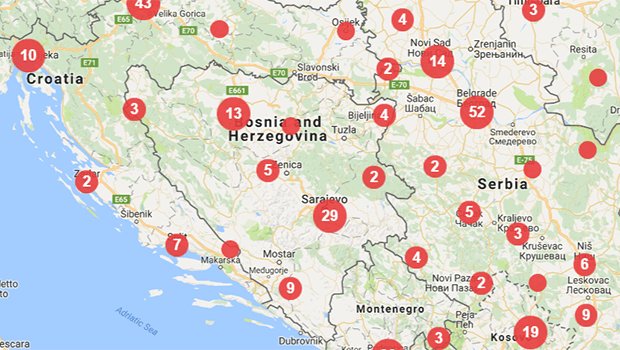

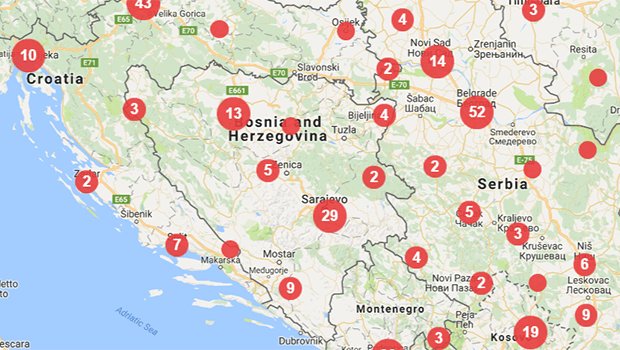

22 Aug 16 | Bosnia, mobile, News and features

University professors, poets and artists signed an open letter in support of three media workers who were targeted with death threats and hate speech. The letter, which was published in the Sarajevo daily Oslobodjenje on 21 July, said that the journalists are “targeted just because they expressed their view which is different from the majority’s”.

“Regardless of whether one agrees or not with the above-mentioned views, instigation of death threats and public lynching through creating a modern day Bosnian Index Librorum Prohibitorum is unacceptable,” the letter said.

The cases were reported to Mapping Media Freedom over three days in July.

In the first incident, Vuk Bacanovic, a journalist for the Radio-Television of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, was fired for allegedly violating the internal rules and the ethical code of the television network. In a Facebook post on his personal page he criticised a public art installation that depicted the federal entity of Republika Srpska as a mass grave and concentration camp. Bacanovic wrote that he “hates the assholes from Sarajevo” who were “talking crap” by saying the city has a multi-ethnic spirit. After articles about the post were published, Bacanovic received numerous death threats via Facebook, regional TV outlet N1 reported.

Nenad Velickovic, editor-in-chief of educational career-oriented magazine Skolegijum, was then verbally harassed and threatened as a result of three articles written by Filip Mursel Begovic, editor-in-chief of the weekly Stav, which were published in June and July. Begovic described Velickovic as a “man with a hidden and dangerous agenda”, “a falsifier” and a “Serbian nationalist” while describing the magazine Skolegijum as “extended arm of Serbian chauvinism”, Analiziraj.ba reported.

The letter was also written in support of the secretary general of BH Journalists’ Association Borka Rudic, who was subjected to verbal harassment by unidentified men after a high-ranking member of the Party of Democratic Action, an ethnic Bosniak political party, described her, amongst other things, as a “lobbyist for Fethullah Gulen”, website media.ba, reports.

The three incidents reflect the ethnic divisions and stereotypes that were re-enforced by the 1992-1995 war in Bosnia. The post-conflict society is governed through a complex political system established by the 1995 Dayton Peace Accords. The power-sharing constitution recognises each of the three major ethnic groups – Bosniaks (Muslims), Serbs (Orthodox) and Croats (Catholics) – as the constituent peoples of Bosnia. In practice, the recognition means that anyone not identified as belonging to one of the three groups could not be elected to hold a public office, despite a 2009 European Court of Human Rights ruling ordering the constitution to be revised.

Following the formula set out in the Dayton Accords, Bosnia and Herzegovina is divided into two entities – the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with majority ethnic Bosniak and ethnic Croatian inhabitants, and the Republika Srpska, with majority ethnic Serbian population. Additionally there is the district of Brcko, which is separate enclave jointly administered by both.

The three groups also differ on the future of Bosnia. Some Bosniaks advocate for a more unitary state, while some Serbs want a more confederate arrangement or even dissolution of the state. At the same time there are Croats that want a separate ethnic entity. The competing visions of Bosnia’s future are heavily influenced by historic and recent incidents including charges of genocide, crimes against humanity and other atrocities that occurred during the 1992-95.

The Centre for Security Governance says that the governing structure “has discouraged inter-group cooperation and reconciliation. Political elites have pandered to ethnic fears, resulting in the electoral victories of ethnonational parties via the phenomenon of ‘ethnic outbidding’.”

Some politicians use friendly media to advocate for further strengthening of ethnic politics, while journalists and intellectuals that argue for strengthening civic identities and bridging ethnic hatred are usually vilified as traitors if they are from the same ethnic background, or enemies, if they are from another ethnicity. All of the cases addressed in the open letter originated in Bosniak nationalist media and were targeted at either another ethnicity or individuals who prefer civic above ethnic identity. Velickovic was described as a “man with a hidden and dangerous agenda” by a Bosniak journalist because he was advocating for non-nationalistic school curriculum.

“The importance of maintaining strong journalistic ethics cannot be underscored enough, especially given the country’s recent history. Members of the media profession must strive to be balanced, refrain from inflaming already tense inter-ethnic relations and guard against being used for political ends,” Hannah Machlin, project officer for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, said.

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, in an open letter also noted that the latest events open a very worrying chapter on the safety of journalists.

“People engaged in investigative reporting and expressing different opinions, even provocative ones, should play a legitimate part in a healthy debate and their voices should not be restricted,” Mijatovic said.

In the current climate, the open letter in support of and signed by people of different ethnicities is a small step forward. Signatory Asim Mujkic, a professor at the faculty of political sciences at the University of Sarajevo, said the cases were a call to action.

“My initial motive was to protest against the mainstream hegemonic ideological view that aggressively imposes itself upon independent and free-thinking intellectuals and public workers that, in the context of Bosnia and Herzegovina, usually targets vulnerable ethnicities for the purpose of its political mobilization,” Mujkic told Index on Censorship.“We need to fire back, especially in such circumstances.”

19 Aug 16 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

The manner in which Gawker — love it or loathe it — has been shuttered is a significant blow to media freedom. The US site will close down after being forced into bankruptcy through a lawsuit funded by billionaire Peter Thiel.

“No one should be able to shut down a news provider simply by using the power of their wealth. That is why Index on Censorship fought so hard to reform libel laws in the UK. A free and pluralistic press is essential to democracy,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said.

19 Aug 16 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Russia, Serbia, Turkey

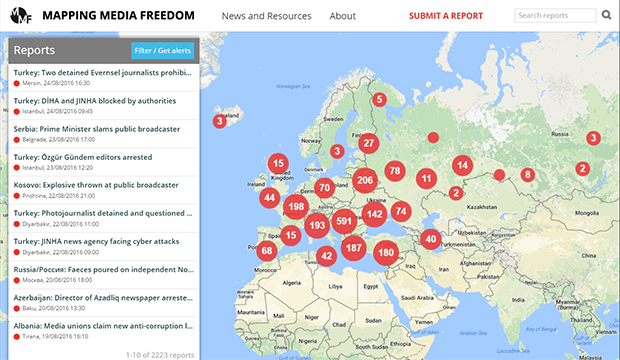

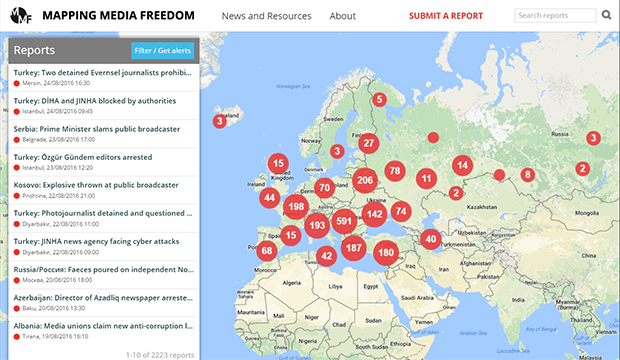

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

16 August, 2016 – IMC TV reporter Gulfem Karatas and cameraman Gokhan Cetin were assaulted and detained while covering the police raid on the daily Ozgur Gundem. Footage of the attack was shared via IMC TV Twitter account, showing police grabbing the camera and physically assaulting the reporter, who is heard screaming in the footage.

Karatas and Cetin were detained along with journalists Günay Aslan, Reyhan Hacıoğlu, Ender Öndeş, Doğan Güzel, Ersin Çaksu, Kemal Bozkurt, Sinan Balık, Önder Elaldı, Davut Uçar, Zana Kaya, Fırat Yeşilçınar and Mesut Karnak.

In an official statement IMC TV said: “During the live broadcast, the police prevented Gulfem Karatas and Gokhan Cetin from reporting and detained them violently along with at least 21 Ozgur Gundem employees. We condemn this unacceptable treatment to our colleagues who were on duty and ask for their immediate release.”

16 August, 2016 – Journalist Vladimir Zivanovic and photographer Boris Mirko, who work for the daily Serbian Telegraph were threatened and insulted while reporting on the illegal construction of an aqua park in the capital Belgrade.

The journalists were in an area of the city where former professional football player Nikola Mijailovic is building the controversial aqua park. Mijailovic approached the journalists and shouted a series of insults about them and their families. He reportedly told them that they should be put in a gas chamber together.

Mijailovic also reportedly tried to bribe them. The journalists have reported the threats to the police and Serbia’s Independent Association of Journalists has condemned the incident.

15 August, 2016 – A court in Baku ruled to uphold a travel ban against investigative reporter Khadija Ismayilova. “Binagadi Court told me because I have no husband, kids or property, I might not be able to return if I leave the country,” Ismayilova said following the hearing in Baku.

Ismayilova was released from prison on 25 May on a suspended three-and-a-half-year sentence.

Also read: Azerbaijan’s long assault on media freedom

16 August, 2016 – The eighth administrative court in Istanbul ordered the closure of the newspaper Ozgur Gundem on the grounds of “producing terrorist propaganda”.

The court order described the closure as “temporary” although no duration appears to be specified in the text of the decision.

Later that day, Ozgur Gundem’s offices were raided by the police.

According to P24, the 23 members of staff were taken into custody. They are: Editor-in-Chief Zana Kaya, journalists Zana Kaya, Günay Aksoy, Kemal Bozkurt, Reyhan Hacıoğlu, Önder Elaldı, Ender Önder, Sinan Balık, Fırat Yeşilçınar, İnan Kızılkaya, Özgür Paksoy (DİHA news agency) , Zeki Erden, Elif Aydoğmuş, Bilir Kaya, Ersin Çaksu, Mesut Kaynar (DİHA), Sevdiye Gürbüz, Amine Demirkıran, Baryram Balcı, Burcu Özkaya, Yılmaz Bozkurt (member of the press office of the Istanbu Medical Chamber), Gülfem Karataş (İMC), Gökhan Çetin (İMC) and Hüseyin Gündüz (Doğu Publishing House).

Also read: Turkey’s continuing crackdown on the press must end

11 August, 2016 – Dmitri Remisov, the Rostov-on-Don regional correspondent for Rosbalt news agency, told the agency that he was repeatedly assaulted by police officers while being questioned at the regional Center for Counteracting Extremism.

According to Remisov, he was asked to come to the CCE to answer questions related to a criminal case “on the preparation of a terrorist act” in Rostov, a city in south-west Russia.

He reported that two police officers asked him whether he knew certain individuals, where most of the people he was asked about were opposition activists.

“Then they asked me if I knew a certain Smyshlayev. I said that I didn’t remember such a person,” Remizov said.“One officer started saying I did know this person in 2009, after which he struck my head three times. Afterwards, he began threatening me, saying he could prosecute me under the criminal law or could have some Nazis punish me.”

After he was questioned another policeman threatened him with physical punishment, saying “we will meet [with you] once again”.

The Rosbalt correspondent received medical care after the questioning. He also filed a complaint against police officers, Rosbalt reported.

18 Aug 16 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile

18 August 2016. Less than six weeks ahead of a constitutional referendum, Azerbaijani authorities have unleashed a new wave of repression to silence critical voices. The undersigned members of the Sport for Rights coalition condemn this renewed crackdown, and call on officials to take immediate steps to improve the human rights situation in the country, starting with the release of political prisoners.

On 12 August, prominent Azerbaijani economist and executive secretary of the opposition Republican Alternative (REAL) movement Natig Jafarli was arrested on charges of illegal entrepreneurship and abuse of power, and sentenced to four months of pre-trial detention. On 17 August, the Court of Appeals rejected the appeal for his release. According to Sport for Rights member the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, Jafarli has been locked up for his “peaceful criticism” of the country’s upcoming constitutional referendum. The charges against Jafarli stem from a criminal case the Prosecutor General’s Office launched against a group of NGOs in 2014. If convicted, Jafarli may face up to eight years of imprisonment.

|

Sport for Rights considers charges against activists to be politically motivated.

|

|

On 13 August, NIDA civic movement activist Elgiz Gahraman was arrested, held incommunicado over the weekend, charged on 15 August with drug possession, and sentenced to four months’ pre-trial detention. Also on 15 August, REAL movement youth activists Elshan Gasimov and Togrul Ismayilov were arrested and sentenced to seven days of administrative detention each on charges of resisting police. Authorities also harassed civic activist and former political prisoner Bakhtiyar Hajiyev, calling him in for questioning and then subjecting him to a court hearing that dragged out over three days, before fining him 100 AZN on charges of “minor hooliganism”.

Sport for Rights considers the charges against Jafarli, Gahraman, and the other activists to be politically motivated, and calls for their immediate and unconditional release, along with the release of all of Azerbaijan’s dozens of political prisoners – including opposition REAL movement leader Ilgar Mammadov, whose release has been ordered by the European Court of Human Rights; journalist Seymur Hezi; and youth activists Ilkin Rustemzade, Giyas Ibrahimov, and Bayram Mammadov.

This spate of repression takes place in the aftermath of Azerbaijan’s latest mega event, the Formula One European Grand Prix, held in Baku in June. It also takes place on the eve of a constitutional referendum set for 26 September, which will decide a series of problematic amendments aimed at further consolidating power in Azerbaijan’s already dominant presidency. The Azerbaijani government’s proposal of these amendments immediately followed July’s coup attempt in Turkey.

Events in Turkey have played a further role in Azerbaijan’s renewed crackdown. On 15 August, the Azerbaijani Prosecutor General’s Office announced it had opened a criminal case against supporters of the Turkish Gulen movement “to prevent illegal actions on the territory of Azerbaijan”. Detained NIDA civic movement activist Elgiz Gahraman was linked to the Gulen movement in an article in the pro-governmental press that also targeted figures of the opposition Popular Front Party and the satellite Azerbaycan Saatı (“Azerbaijan Hour”) programme, signalling possible further pressure to come. On 17 August, the Caucasus University in Baku announced it had fired 50 Turkish instructors for alleged links with the Gulen movement.

Broadcast of Azerbaijan Saatı was stopped on 27 July when Turkish television station Barış TV, which carried the programme, was among the media outlets shut down by a presidential decree in Turkey, alleging their connection to the Gulen movement. The transmission of another rare critical news source on developments in Azerbaijan, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s programme Azadlıq (“Freedom”) A-LIVE, was halted without explanation by Türksat satellite on 8 August. In Azerbaijan, private national television station ANS TV remains off the air following a court order on 29 July to revoke the station’s license in connection with an interview it had planned to broadcast with Fethullah Gulen.

All of this occurs against the backdrop of a dire overall human rights situation in Azerbaijan. The media remains completely dominated by the state, and critical journalists operate in a climate of fear. Excessive restrictions remain on civil society, severely hindering the ability of independent NGOs to operate. Travel bans continue to be used against journalists, activists, and politicians – including journalists Khadija Ismayilova, whose appeal to lift her travel ban was denied on 15 August, and Elchin Mammad, who was detained when trying to cross the Azerbaijani border on 9 August.

The Sport for Rights coalition calls for the Azerbaijani authorities to immediately cease these gross and systemic violations and take steps to improve the human rights situation in the country, starting with the immediate and unconditional release of political prisoners held for their peaceful political activities or exercise of their right to freedom of expression. Sport for Rights further calls for sustained attention to Azerbaijan by the international community, and concrete action to hold the Azerbaijani government accountable for its human rights obligations.

Supporting organisations:

ARTICLE 19

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Civil Rights Defenders

Freedom House

Freedom Now

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights

Human Rights House Foundation

Index on Censorship

Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety

International Media Support

International Partnership for Human Rights

Netherlands Helsinki Committee

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN America

PEN International

People in Need

Reporters Without Borders

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

Related:

Index on Censorship’s Azerbaijan campaign

Azerbaijan’s long assault on media freedom

17 Aug 16 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, United Kingdom

On Tuesday, the UK learned that radical cleric Anjem Choudary had been convicted under Section 12 of the UK’s 2000 Terrorism Act, which makes it a crime to invite “support for a proscribed organisation”. Choudary had long argued that, in advocating his support for the creation of an Islamic state and the imposition of sharia law, he was simply exercising his right to free speech. And this was true. Like any other citizen, Choudary should be allowed to express his political views, no matter how vile or abhorrent.

But there is also no doubt that Choudary trod a very careful and deliberate line. Choudary understands that in a free and democratic society (the kind to which Choudary would like to see a violent end), the only occasions on which free speech should be curtailed is when the speech provokes – or presents a clear and imminent danger of provoking – violence. Beyond that line, no one, including Choudary, should be prevented from expressing their view.

If free speech is to mean anything, then free speech rights must apply equally.

|

The immediate question, then, is whether Choudary was advocating violence? In Index’s view, he was. Choudary was convicted of encouraging followers to join IS, a proscribed terrorist organisation. Although he did not directly incite violence, he was calling on others to join a group whose avowed aims are victory through violence. In this context, the definition of a proscribed group becomes crucial. Proscribed groups should only be ones that directly use and incite violence, not simply political parties whose views do not chime with those of the government or even the majority of the population. This is a vital line.

If free speech is to mean anything, then free speech rights must apply equally: as much to those whose views we abhor as to those whom we support. Choudary deliberately exploited liberal values to advocate wholly illiberal ones. So it is critical that in responding to the likes of Choudary that we do not respond by shifting further towards the kind of illiberal society he favours. The laws which (should) protect Choudary’s right to envisage the imposition of an Islamic state are the same that protect the rights of the rest of us to voice our opposition: the best way to dispute views you disagree with is openly, rather than driving them underground where they can grow.

Index is concerned at the current direction of travel in anti-extremism law and its damaging implications for free speech. New leglisation is currently under consideration that would target those who advocate extremist views but do not directly encourage violence. This could include banning orders that would prevent non-violent extremists from speaking or publishing – a move that risks undermining the democratic judicial process, as David Anderson, the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation told BBC’s Today programme.

This is a dangerous road to go down. The definition of terrorism is already contentious and further defining ‘non-violent’ extremism almost impossible. Indeed, Christian groups have already expressed concern that the proposed new law would, for example, prevent an opponent of gay marriage from expressing such a view. Nor should we use the examples of Choudary’s use of social media to greenlight enforcing social media companies to act as arms of the law, making decisions about content removal that should be made by courts.

Across the world, Index defends the rights of those who express views their government deems ‘extremist’. Choudary is an extremist. His views are repugnant and to be countered at every opportunity, but he should be allowed to express them.

More information about UK law and counter terrorism

17 Aug 16 | Academic Freedom, Bahrain, Campaigns -- Featured, Middle East and North Africa, mobile, News and features

Protesters in London demand the release of Abduljalil al-Singace, July 2015.

One year has passed since Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley sent a copy of the publication – Fired, Threatened, Imprisoned… Is Academic Freedom Being Eroded? – to jailed Bahraini academic, human rights activist and writer Abduljalil al-Singace to mark his 150 days on hunger strike.

Al-Singace’s hunger strike ended on 27 January 2016 after 313 days, but he remains in prison.

In a letter accompanying the magazine, Jolley aired concerns that al-Singace – who had been protesting prison conditions while being held in solitary confinement – had suffered torture and called on the Bahraini authorities to ensure he “had access to the medical treatment he urgently requires”.

Index magazine editor Rachael Jolley pens letter to Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior regarding al-Singace, 17 August 2015.

On 15 March 2011 Bahrain’s king brought in a three-month state of emergency, which included the through establishing of military courts known as National Safety Courts. The aim of the decree was to quell a series of demonstrations that began following a deadly night raid on 17 February 2011 against protesters at the Pearl Roundabout in Manama, when four people were killed and around 300 injured.

Over 300 individuals were subsequently convicted through National Safety Courts, often for speaking out against the government or exercising their right to assemble freely. Many were punished simply for supporting or being part of the country’s opposition movement.

On a midnight raid at his home on 17 March 2011, al-Singace was arrested at gunpoint. During the arrest, he was beaten, verbally abused and his family threatened with rape. Disabled since his youth, al-Singace was forced to stand without his crutches for long periods of time during his arrest. Masked men also kicked him until he collapsed. The Bahraini authorities placed him in solitary confinement for two months. During this time the guards starved him, beat him and sexually abused him.

Al-Singace is part of what is known as the Bahrain 13, a group of peaceful activists and human rights defenders imprisoned in Bahrain in connection with their role in the February 2011 protests.

On 22 June 2011 a military court sentenced all members of the Bahrain 13 to between five years and life in prison, on trumped-up charges of attempting to overthrow the regime, “broadcasting false news and rumours” and “inciting demonstrations”.

Evidence used against them was extracted under torture, but this didn’t prevent their sentences being upheld on appeal in September 2011, at a civilian court in May 2012 and in January 2013 at the Court of Cassation. The Bahrain 13 has now exhausted all domestic remedies and are currently serving their sentences Jau prison, notorious for torture and ill treatment.

During their arrest and detention, the Bahrain 13 were subject to beatings, torture, sexual abuse and threats of violence and rape towards themselves and members of their family by police and prison authorities. Eleven of the 13 remain in prison.

The group consists of:

Al-Singace

Sheikh Abduljalil al-Muqdad, a religious cleric and a co-founder of the al-Wafaa Political Society. During his detention he has been beaten, tortured and told his wife would be raped.

Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, a human rights activist and co-founder of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights. On 8 February 2012, he began a hunger strike to protest his wrongful detention and treatment in prison. He ended his hunger strike after 110 days on 30 May 2012. He went on hunger strike again in April 2015 to protest against the torture of prisoners at Jau.

Salah al-Khawaja, a prominent human rights activist, marriage consultant and the brother of Abdulhadi. The government previously arrested Salah in the 1980’s and 1990’s for engaging in political activity against the government. He was released on 19 March 2016.

Abdulhadi al-Makhdour, a religious cleric and political activist. Authorities prevented him from showering and performing his daily prayers. They spat in his mouth and forced him to swallow. They also denied him access to a lawyer and barred him from contacting his family.

Mohammed Habib al-Muqdad, a religious cleric and the president of the al-Zahraa Society for Orphans. During his time in prison he was sexually assaulted with sticks and forced to gargle his own urine. Security guards also electrocuted him on his body and genitals.

Mohammed Ali Ismael, a prominent political activist in Bahrain. During his imprisonment, he has been beaten and verbally abused.

Abdulwahab Hussain, a life-long political activist and leader of the Al Wafaa political opposition society. He was previously detained for six months in 1995 and for five years between 1996 and 2001. He was diagnosed with multiple peripheral polyradiculoneuropathy, a condition which affects the body’s nerves, in 2005 and suffers from sickle-cell disease and chronic anaemia. His health conditions have worsened as a direct result of the torture and ill-treatment, while medicine and treatment have been denied to him. During his current sentence he has contracted numerous infections.

Mohammed Hassan Jawad, human rights activist who campaigns for the rights of detainees and prisoners who has been jailed a number of times since the 1980s. During his current imprisonment, he was electrocuted and beaten with a hose.

Sheikh Mirza al-Mahroos, a religious cleric, a social worker, and the vice-president of the al-Zahraa Society for Orphans. During his time in prison, Al-Mahroos has been denied medical treatment for severe pain in his legs and stomach. Despite having the proper documentation, he was not permitted to visit his sick wife, who later died in early 2014.

Hassan Mushaima, a political activist and leader of the Al Haq opposition society in Bahrain who has been arrested several times for his pro-democratic activities. He was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2010, which he was successfully treating at the time of his arrest. Medical results have been denied to him in prison.

Sheikh Saeed al-Noori, a religious cleric and member of the al-Wafaa Political Society. During his detention he has been tortured, forced to stand for long periods of time and had shoes stuffed in his mouth.

Ebrahim Sharif, the former president of the National Democratic Action Society. He is a political activist and has campaigned for democratic reform and equal rights. On 19 June 2015, Sharif was released following a royal pardon, only to be rearrested on 12 July 2015. He was charged with “inciting hatred against the regime” for a speech he delivered in commemoration of 16-year-old Hussam al-Haddad, who was shot and killed by police forces in 2012. He was released again in July 2016 and remains out of prison but the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy he is at risk of being arrested again because of an appeal by prosecutors.

Source: The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy.

Also read:

– Bahrain continues to use arbitrary detention as a weapon to silence critics

– Bahrain: critics and dissidents still face twin threat of statelessness and deportation

Fruzsina Katona

Fruzsina Katona

Each week, Index on Censorship’s

Each week, Index on Censorship’s