16 Aug 16 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

Index strongly condemns the indefinite closure of newspaper Özgür Gündem by a Turkish court.

The silencing — even temporarily — of one of Turkey’s last independent papers underscores the severe erosion of freedom of expression in the country. This crackdown on critical voices has accelerated since the attempt to overthrow the country’s democratically elected and increasingly autocratic president Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

|

The silencing — even temporarily — of one of Turkey’s last independent papers underscores the severe erosion of freedom of expression in the country.

|

|

“Waves of arrests rippling across the country have swept up journalists, academics and even artists and are rightly raising concerns around the world. This latest attack on media freedom sends a clear signal that president Erdogan is intent on playing politics with the public’s right to information and journalists’ right to report,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

Özgür Gündem, a paper that gives voice to the country’s Kurdish minority, has — along with other outlets — been the target of restrictive government policies. In May, officials used a paper-sponsored solidarity campaign to target journalists and editors that participated to stifle any criticism of the government’s renewed fight with armed factions affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The resulting investigation saw journalists interrogated and detained for articles that the government said were spreading “terrorist propaganda”.

As part of its post-coup purge, the government has targeted at least 70,000 people, who are accused of ties to the Gulenist movement that President Erdogan says is behind the failed assault. In addition, 151 media outlets have been closed and at least 77 journalists have been detained, making Turkey the largest jailer of reporters in the world.

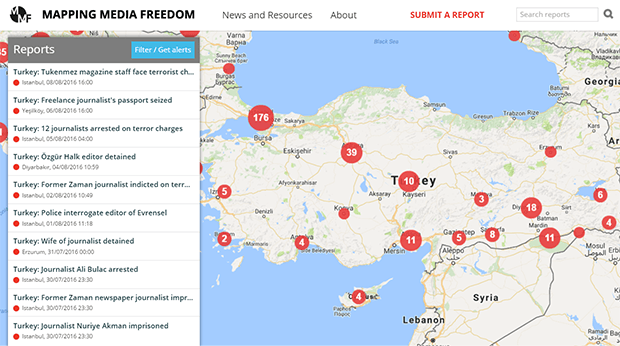

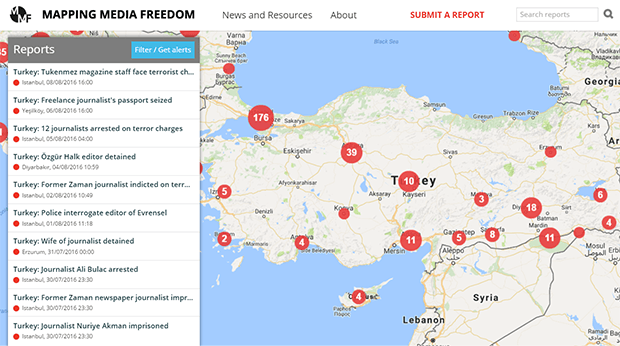

“Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project has been monitoring the grim toll the post-coup purge is having on Turkey’s media freedom. In the month since the failed coup, there have been 61 verified and serious threats to press freedom. In contrast, the other 41 counties monitored by the project accounted for 51 reports,” Hannah Machlin, Mapping Media Freedom project officer said.

16 Aug 16 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Azadliq journalist Seymur Hezi was arrested in August 2014. He was subsequently convicted of aggravated hooliganism and sentenced to five years in prison.

Azerbaijan has never had a strong record on press freedom. Since independence, the country’s journalists have been mistreated, while independent and opposition newspapers faced constant libel charges and other harassment from local law enforcement or criminal elements.

Journalists and outlets that support government policies are left alone to fill their pages with praise, while those who take a more critical approach are punished. Official court documents detail how journalists have been sent to prison on trumped-up charges of hooliganism, extortion, trafficking, and instigating mass protests and violence.

In practice, however, targeted journalists reported on official corruption, criticised extravagant government spending or documented illegal evictions. While the country’s leaders and key decision makers pay lip service to media freedom, the government continues to hunt down journalists, activists and human rights defenders.

Periodic waves of arrests have created a sense of fear that has suffocated the country’s journalists. Independent media — like Index award-winning Azadliq — have been pushed into bankruptcy through the withholding of funds and spurious libel litigation. Even media organisations based outside the country — like meydan.tv — have been subject to harassment and punitive investigations. Azerbaijan’s small but remaining mass of independent voices is shrinking.

The timeline, beginning in 2003, includes journalists and bloggers who have been arrested and sentenced on bogus charges.

TimelineJS Embed

15 Aug 16 | Americas, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

We the undersigned organisations defending freedom of the press and access to information are deeply concerned by the cybercrime law adopted today in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Several provisions of this bill pose a serious threat to freedom of the press, the free flow of online information, and public debate.

Defamation in print, written and broadcast media is punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment under Saint Vincent’s penal code, pre-dating the adoption of the Cybercrime Law, but the new legislation extends criminal defamation to online content.

In addition to broadening criminal defamation to include online expression, the law also introduces worryingly vague and subjective definitions of cyber-harassment and cyber-bullying, both of which are punishable by imprisonment.

The negative value and chilling effect that criminal defamation places on freedom of expression and of the press have been well noted at the local, regional and international level, and states have been repeatedly called on to abolish criminal defamation laws. The issue of criminal defamation has particular importance in the Caribbean, where a similar law was adopted in Grenada in 2013 and subsequently amended after international outcry. Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana are currently considering similar legislation now under critical review by national, regional, and international stakeholders.

The steps taken today in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines to strengthen criminal defamation laws and stifle online dissent and discussion could reverse the positive legislative trend in the Caribbean and serve as a negative example for Saint Vincent’s regional neighbors. It is therefore our view that the law as adopted today must be revised and criminal defamation must be abolished, and we urge the government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines to do so as soon as possible.

Signed,

Association of Caribbean Media Workers

Committee to Protect Journalists

International Press Institute

Reporters Without Borders

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Independent Journalism – Romania

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Freedom Forum

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Human Rights Network for Journalists – Uganda

Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

Index on Censorship

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Rights Agenda

Media Watch

Pacific Freedom Forum

Pacific Islands News Association

Pakistan Press Foundation

Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

PEN International

Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

15 Aug 16 | Bahrain, Bahrain Letters, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile, Statements

Rt Hon Boris Johnson

Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

King Charles Street Whitehall

London SW1A 2AH

15 August 2016

Dear Mr Johnson,

First, may we congratulate you on your recent appointment as Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs.

We write to raise our deep concern over the current ambassador from the Kingdom of Bahrain to the UK, Sheikh Fawaz bin Mohammad Al Khalifa, on his recent statements and record on press freedom, and urge you to raise the concerns set out below to the Government of Bahrain.

Last month, on 20 July, the Bahrain embassy in the UK released a statement in support of the actions of the Information Affairs Authority (IAA), which brought a case against Bahraini journalist Nazeeha Saeed. Ms. Saeed has worked as correspondent for France24 for seven years, and for Radio Monte Carlo Doualiya for 12 years. She was charged with working for international media outlets without a license. Her case is just the latest in a series of regressive actions targeting critical journalists, creating an environment where a free fourth estate cannot function.

The Bahrain embassy’s statement reported that the IAA had lodged a legal complaint against Ms. Saeed for illegally working as a foreign correspondent, that Ms. Saeed’s foreign correspondence license expired ‘over 150 days’ ago, and that she was warned of legal action.1 None of this is true. The undersigned NGOs have seen a letter by the IAA from June 2016 denying her license renewal, which she had applied for at the end of March 2016 (some 110 days earlier to the embassy’s statement, not 150). The IAA did not in fact warn her of legal action in the letter.

It is not innocuous that Sheikh Fawaz, as ambassador to the United Kingdom, had the embassy publish this statement in support of the IAA and we see this statement as a reflection of Bahrain’s antipathy towards a free press, and as Sheikh Fawaz’s direct role in antagonising the press.

The IAA is the government body that regulates the press, issues journalist licenses, and operates Bahrain News Agency and the state-run Bahrain TV. Sheikh Fawaz Al Khalifa, prior to becoming ambassador, was the first president of the IAA between 2010 and 2012, overseeing the institution during the Arab Spring. In that time, the government systematically cracked down on political and civil freedoms. The IAA was responsible for suspending the only independent newspaper, aiding in the censorship of the press and the deportation of foreign-national journalists, and in spreading hate speech through IAA-controlled TV stations.

Journalists interviewed by the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy have told us that press relations were calmer before Sheikh Fawaz’s 2010-2012 presidency of the IAA. Sheikh Fawaz’s appointment as media chief in July 2010 coincided with the arrest and torture of opposition politicians and activists in the lead-up to Bahrain’s November 2010 General Elections, actions which precipitated the Arab Spring protests. Journalists state that government censorship of the press increased substantially with the formation of the IAA under Sheikh Fawaz.

In May 2011, Ms. Saeed was summoned to a police station in connection to the police killing of a protester she had witnessed. There, police detained her and tortured her into signing a confession, as reported by Human Rights Watch.2 To date Ms. Saeed has been denied justice by Bahrain’s courts.3 The IAA, despite its responsibilities to protect journalists, did not support her. Soon after Ms. Saeed’s detention, BBC Arabic interviewed Sheikh Fawaz, then-IAA president, asking him: “Why is a journalist who has come to report these events treated in this way?” He replied: “She does not have any license to report for the French news agency.”4 In fact, Ms. Saeed had a license at that time, and has done throughout her career, until the IAA’s refusal of her latest renewal in April 2016. Sheikh Fawaz not only failed to protect a vulnerable journalist, he intentionally spread falsehoods justifying her mistreatment.

Ms. Saeed’s case is not the only one in which Sheikh Fawaz has played a role. The Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry, the accepted record of rights violations during 2011, notes (para. 1611) how Sheikh Fawaz’s Deputy Assistant at the IAA summoned an Iraqi journalist working for the only independent newspaper, Al Wasat, for a meeting in April 2011 during an imposed State of Emergency. When the journalist arrived at the IAA offices, police arrested, beat and threatened him, then deported him that same evening.5

Al Wasat newspaper was subjected to a smear campaign led by the IAA itself. On 2 April 2011, the IAA-operated Bahrain TV broadcast a two-hour live show antagonising Al Wasat and immediately afterwards, the IAA suspended the newspaper, only allowing it to resume publication after the resignation of its senior editorial staff.6 The newspaper was not alone suffering this crackdown on free expression: Bahrain TV broadcast programmes identified and vilified celebrity protestors throughout the Arab Spring period. Athletes, including national football team players, who called on live broadcasts to defend their appearance at protests, were arrested and subjected to torture within days of doing so.7 The IAA-run Bahrain TV, which we reiterate would have been executing policy set by the president, Sheikh Fawaz, has never been held to account for its role inciting hatred against legitimate political protest and the targeting of specific persons.

Journalism as a whole was under threat during Sheikh Fawaz’s leadership of the IAA. The repression of independent journalists and media under his watch was on a scale similar to that seen in countries like Turkey and Egypt, which are known for state censorship of the press.

A sure indicator of this is in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index, which ranks each country on press freedom, with the 1st country having the freest press. Bahrain’s ranking, which stood at 119th in 2009, the year before Sheikh Fawaz’s IAA presidency, fell by 46 rungs to 165th by 2012, the year his presidency ended. This was the greatest fall in rankings Bahrain ever saw.

Bahrain’s ranking currently sits at 162 (with this latter rise in rank due mainly to the addition of countries ranked below Bahrain). As a point of comparison, the 2016 Press Freedom Index 2016 respectively ranked Turkey and Egypt at 151 and 159. The rankings reflect Sheikh Fawaz’s devastating leadership of the state media body and the long shadow left on press freedom.

It was for these reasons that the community of press freedom activists, rights defenders and NGOs greeted Sheikh Fawaz’s appointment as ambassador to the United Kingdom with alarm. His embassy’s latest statements on the case of Ms. Nazeeha Saeed, for which the history extends back to his IAA presidency in 2011, calls back his direct role in repressing Bahrain’s press and journalists. His role in allowing the incitement of hatred against pro-democracy protesters on his watch, and his continued public attempts to mislead on the cases of journalists like Ms. Saeed, are indications that neither he nor the country he represents share the key British values of the right to free speech and individual liberty, nor in the universally recognised right to freedom of expression, as protected under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Kingdom of Bahrain’s choice of a person with a key role in repressing freedom of speech as their ambassador to the United Kingdom reflects Bahrain’s unchanged, poor attitudes towards freedom of speech and human rights more generally.

We therefore urge you to address this promptly and raise these issues surrounding Sheikh Fawaz’s past and current involvement in the violations of press freedom with the Government of Bahrain.

Yours sincerely,

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy

Index on Censorship

Reporters Without Boarders

1 Bahrain Embassy in London, Press Release: Information Affairs Authority Clarifies Regulation for Foreign Correspondents Related to Nazeeha Saeed, 20 July 2016, http://us12.campaign- archive1.com/?u=adae2d71fee280549ad890919&id=79fd8c6d53.

2 Human Rights Watch, Criminalizing Dissent, Entrenching Impunity: Persistent Failures of the Bahraini Justice System Since the BICI Report, 28 May 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/05/28/criminalizing-dissent- entrenching-impunity/persistent-failures-bahraini-justice.

3 Reporters Without Borders, RSF Demands Justice for Bahraini Journalists Tortured in 2011, 20 November 2015, https://rsf.org/en/news/rsf-demands-justice-bahraini-journalist-tortured-2011.

4 Bahrain TV on Youtube, IAA President Interview on BBC Arabic – 27 May 2011, 27 May 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDlClo2AIuE.

5 Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI), Report of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry, November 2011, para. 1611, http://www.bici.org.bh/BICIreportEN.pdf.

6 BICI, Report of the BICI, para. 1592.

7 ESPN (mirror), ESPN E:60: Athletes of Bahrain, 8 November 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wfhPWwhWlJU.

12 Aug 16 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured

We, the undersigned civil society groups located worldwide, write to you to once more condemn the ongoing harassment of human rights defenders in Bahrain and call on you to drop all charges against Sheikh Maytham Al-Salman.

Sheikh Maytham Al-Salman has been called for interrogation at Ministry of Interior on Sunday 14 August 2016 due to exercising his right in defending religious freedom and exposing human rights violations in Bahrain. This latest reprisal is part of a disturbing trend of crackdowns by the Bahraini government against human rights defenders and civil society organizations.

Sheikh Maytham is an internationally respected interfaith leader and human rights advocate. His work focuses on defending religious freedom and countering violent extremism while supporting the right to freedom of expression in accordance with international human rights standards. In October of 2015, Sheikh Maytham was honoured for his work with the Interfaith Communities for Justice and Peace “Advocate for Peace” award.

Bahraini authorities have harassed Sheikh Maytham on numerous occasions in the past, including two separate incidents in 2015 when he was detained for his human rights activities. He was also summoned in connection to the content of a speech he gave on 27 December, the anniversary of the arrest of prisoner of conscience Sheikh Ali Salman, in which he drew attention to the violations of international fair trial standards that took place.

This harassment is in violation of Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Bahrain has been a signatory to since 2006. It also contradicts the obligations of the state to protect human rights defenders, as derived from their obligation to protect all human rights under Article 2 of the ICCPR.

Rather than ensure their protection, Bahrain has made a habit out of persecuting dissidents and activists. Sheikh Maytham joins other high-profile individuals like BCHR President Nabeel Rajab, activist Zainab al-Khawaja and human rights defender Naji Fateel that have been targeted for their work and denied their right to freedom of opinion and expression.

The undersigned call on the Government of Bahrain to allow the important work of Sheikh Maytham and others who bring human rights violations to light to be conducted unimpeded, as provided for under the ICCPR and other relevant international human rights standards by taking the following steps:

- Drop all charges pending against Sheikh Maytham al-Salman for exercising his right to freedom of speech;

- Release all prisoners who have been convicted for their political opinions; and

- Fully comply with the recommendations of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI); particularly those that ensure the right to freedom of expression, opinion and assembly are respected.

12 Aug 16 | Belarus, Germany, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Netherlands, News and features, Romania, Turkey

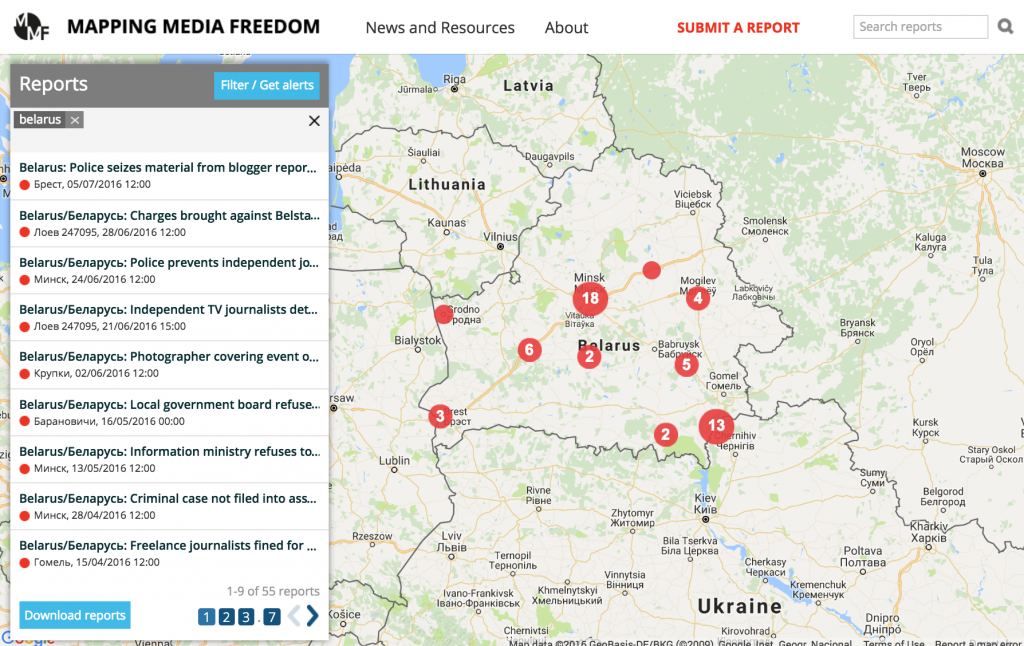

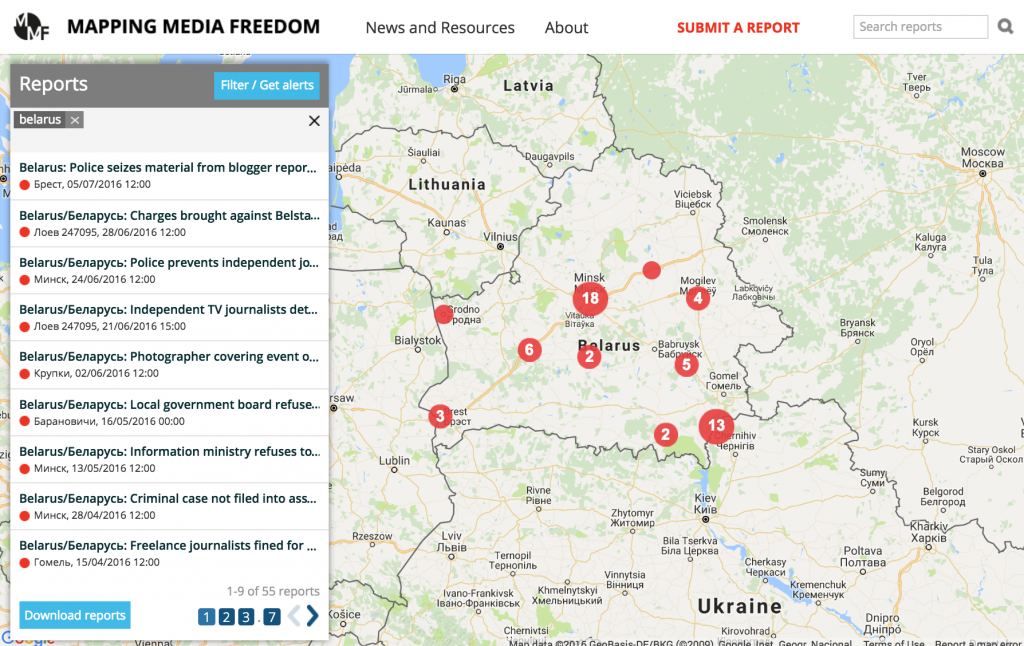

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

5 August, 2016 – Twelve journalists were arrested on terror charges following a court order, independent press agency Bianet reported.

According to Bianet: “The court on duty has ruled to arrest Alaattin Güner, Şeref Yılmaz, Ahmet Metin Sekizkardeş, Faruk Akkan, Mehmet Özdemir, Fevzi Yazıcı, Zafer Özsoy, Cuma Kaya and Hakan Taşdelen on charges of “being a member of an armed terrorist organisation” and Mümtazer Türköne, columnist of the now closed Zaman Daily on charges of “serving the purposes of FETÖ (Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation)” and Hüseyin Turan and Murat Avcıoğlu on charges of “aiding a [terrorist] organization as non-member”.

Warrants for the detainment of all 13 Zaman newspaper journalists were issued on 27 July 2016 by Turkish authorities.

Also read: 200 Turkish journalists blacklisted from parliament

4 August, 2016 – Monica Gubernat, a member and chairperson of the National Audiovisual Council of Romania, cut off the live transmission of a council debate, news agency Mediafax reported.

An ordinance says that all meetings of the council must be broadcasted live on its website.

The institution has recently purchased equipment to broadcast debates, which was set to go live on 4 August, 2016. A member of the council, Valentin Jucan, even issued a press statement about the live broadcast.

The chairperson, Monica Gubernat was opposed to it, saying that she was not informed about the broadcast, and asked for a written notification about the transmission.

ActiveWatch and the Centre for Independent Journalism announced they would inform the supervisory bodies of the National Audiovisual Council of Romania and the culture committees of the Parliament about the “abusive behavior of a member of the council” and asked for increased transparency within this institution.

The National Audiovisual Council of Romania is the only regulator of the audiovisual sector in Romania. Their job is to ensure that Romania’s TV channels and radio stations operate in an environment of free speech, responsibility and competitiveness. In practice, the council’s activity is often criticised for its lack of transparency and their politicised rulings.

2 August, 2016 – British blogger Graham Phillips and freelance journalist Billy Six, forcibly entered the offices of non-profit investigative journalism outlet Correctiv, filmed without permission and accused staff of spreading lies, the outlet reported on its Facebook page on Wednesday 3 August.

According to Correctiv’s statement, Phillips had been seeking to confront Marcus Bensmann, the author of a Correctiv article which claimed that Russian officers had shot down the passenger airplane crossing over Ukraine in July 2014.

Phillips maintains the Ukrainian military is responsible for the crash.

2 August, 2016 – Police officers prevented freelance journalist Dzmitry Karenka from filming near the Central Election Commission office located in the Belarusian Government House in Minsk, the Belarusian Association of Journalists reported.

The journalist reported intended to film a video on the last day when candidates for the House of Representatives, Belarusian lower chamber, could register.

At 6am he was approached by police officers who told him that administrative buildings in Belarus can be filmed “only for the news” and asked him to show his press credentials which he didn’t have as he is a freelance journalist.

Karenka told the Belarusian Association of Journalists that he spoke with the police for over an hour before he was released and advised not to film administrative buildings.

Also read: Belarus: Government uses accreditation to silence independent press

1 August, 2016 – The website of the Dutch edition of Turkish newspaper Zaman Today was hit by a DDoS attack, broadcaster RTL Nieuws reported.

The website, known to be critical of the Erdogan government, was offline for about an hour.

An Erdogan supporter reportedly announced an attack on the website earlier via Facebook. Zaman Today said it will be pressing charges against him.

Also read: Turkey’s media crackdown has reached the Netherlands

11 Aug 16 | Asia and Pacific, mobile, News and features, Pakistan

Farieha Aziz, director of 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award winner Bolo Bhi (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Pakistan’s National Assembly passed a controversial Prevention of Electronics Crimes Bill on Thursday 11 August. The bill will permit the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority to manage, remove or block content on the internet.

Many critics say the bill is too overarching and punishments too severe. It also leaves children as young as 10 liable for punishment.

Farieha Aziz, director of Index-award winning Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit fighting for internet freedom, has been campaigning against the bill for over a year. Last month, Aziz told Index: “It’s part of a regressive trend we are seeing the world over: there is shrinking space for openness, a lot of privacy intrusion and limits to free speech.”

Last week, Aziz was selected by the Young Parliamentarians Forum – a bi-partisan forum with representation from all political parties – as one of the 10 Youth Champions of Pakistan. Yesterday – the day before the bill passed – each recipient was given three minutes to speak to the speaker of the National Assembly, Sardar Ayaz Sadiq, and other parliamentarians.

Yesterday, Aziz used her three minutes to criticise the bill based on the below letter to members of YPF. She emailed a similar letter to Ayaz Sadiq, who left before she gave her speech.

Dear Members of YPF,

Thank you for nominating and selecting me as one of the 10 youth champions of Pakistan.

I stand before you today apparently in recognition of efforts made to secure the rights of Internet users. I regret though that this is no moment for personal recognition or glory, not when the future of the youth of Pakistan stands threatened. What is that threat? The Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill, which is on today’s orders of the day of the National Assembly, set to receive the approval of parliament and become law.

For over a year, not just I, but many citizens and professionals fought long and hard to fix this bill. We engaged with the government and opposition. Provided input to make the law better. We never said there shouldn’t be a law but that the law needed to respect fundamental rights and due process. While we found many allies among you – parliamentarians without whose efforts it would have been an even more difficult struggle – there were many part of the same system who labelled us as agents and propagandists.

On one occasion, the doors of parliament house were shut upon us. Stack loads of written input was disregarded and we were told we were just noise-makers who’d given nothing at all.

How I wish the certificate awarded today was actually a significantly amended version of the bill. A bill that did not trample on the rights of citizens. A bill that factored in the input we’d provided. I have come here today not for the certificate, but to ask you, if you will commit to the youth of this country beyond certificates?

The youth of this country is losing hope. I come to ask you if you will do all that is in your power to do, to restore it. If you want to give the youth of this country hope, then do not dismiss them. Do not stick labels. Do not isolate them. They don’t need certificates to give them hope. They need to see that things will be done differently – that their input will be considered and that you will constructively engage with them. That you will enter questions, and motions and resolutions on vital issues that concern citizens. That you will wage a struggle within your parties to make them see differently on issues. And that you will use your vote when it counts, and block legislation that seeks to take away our constitutionally guaranteed freedoms and rights.

If the bill is passed today, in its current form, the message that will go out to the youth of Pakistan is that there is no room or tolerance for thinking minds and dissenting voices. Should the youth inquire and raise questions, a harsh fine and long jail term awaits them. Is this the future you want to give the youth of Pakistan? If not, then when you go to the National Assembly today at 3pm, stop the bill from becoming law. Allow time to fix it.

Show the youth of this country that not only will you recognize efforts outside parliament; but that you will also honour these efforts by casting your vote to protect their rights inside parliament too. If you do this, that would be true recognition.

Thank you.

Farieha Aziz

Concerned citizen, digital rights activist and journalist

11 Aug 16 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

The number of threats to media freedom in Turkey have surged since the failed coup on 15 July.

One of the most vital duties of a journalist — in any democracy — is to report on the day-to-day operations of a country’s parliament. Journalism schools devote much time to teaching the deciphering budgets and legal language, and how to report fairly on political divides and debates.

I recalled these studies when I read an email Wednesday morning from an Ankara-based colleague. I smiled bitterly. The message included a link to an article published in the Gazete Duvar, which informed that 200 journalists had been barred from entering the home of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. Security controls at the two entrances of the failed-coup-damaged building had been intensified and journalists were checked against a list as they tried to enter.

The reason for the bans? Most of those who were blocked worked for shuttered or seized outlets alleged to be affiliated with the Gülenist movement.

Parliament, though severely damaged by bombing during the night of the coup attempt, is still open. For any professional colleague, these sanctions mean only one thing: journalism is now at the absolute mercy of the authorities who will define its limits and content.

Many pro-government journalists do not think the increasingly severe controls are alarming. “It is democracy that matters,” they argue on the social media. “Only the accomplices of the putschists in the media will be affected, not the rest.”

If only that were true. Reality proves the opposite. Along with the closures of more than 100 media outlets, a wide-scale clampdown on Kurdish and leftist media is underway. Outlets deemed too critical of government policies have come under post-coup pressure.

Late Tuesday, pro-Kurdish IMC TV reported that the official twitter accounts of three major pro-Kurdish news sources — the daily newspaper Özgür Gündem and news agencies DIHA and ANF — were banned. Some Kurdish colleagues interpret the sanctions as part of an upcoming security operation in the southeastern provinces of Diyarbakır and Şırnak.

What I see is a new pattern: in the past three-to-four days, many Twitter accounts of critical outlets and individual journalists have been silenced. An “agreement” appears to have been reached between Ankara and Twitter, but no explanation has yet been given.

For days now, many people have been kept wondering about the case of Hacer Korucu. Her husband, Bülent Korucu, former chief editor of weekly Aksiyon and daily Yarına Bakış, is sought by police after an arrest order issued on him about “aiding and abetting terror organisation”, among other accusations. She was arrested nine days ago as police had told the family that “she would be kept until the husband shows up”.

The Platform for Independent Journalism provided more insight on Hacer Korucu’s detention and subsequent arrest. The motive? She had taken part in the activities of the schools affiliated with Gülen Movement and attended the Turkish Language Olympiade.

Hacer Korucu’s case, without a doubt, shows how arbitrary law enforcement has become in Turkey. As a result no citizen can feel safe any longer.

“She is a mother of five,” was the outcry of Rebecca Harms, German MEP. “A crime to be married to a journalist?”

How do we now expect an honest Turkish or Kurdish journalist to answer this question? By any measure of decency, the snapshot of Turkey in the post-putsch days leaves little suspicion: emergency rule gives a free reign to authorities who feel empowered to block journalists from covering the epicenter of any democratic activity — parliament — and let relatives of journalists suffer.

Meanwhile, we are told on a daily basis that democracy was saved from catastrophe on that dreadful July evening and it needs to be cherished.

But, like this? How?

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

10 Aug 16 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Despite repeated calls by international organisations for reform, Belarus’ regime for press accreditation continues to help the government maintain its monopoly on information in one of the world’s most restrictive environments for media freedom.

The government of president Aleksandr Lukashenko uses the Law on Mass Media to control who reports and on what in an arbitrary procedure that is open to manipulation. While Article 35 sets out journalists’ rights to accreditation, Article 1 of the law defines the process as: “The confirmation of the right of a mass medium’s journalists to cover events organised by state bodies, political parties, other public associations, other legal persons as well as other events taking place in the territory of the Republic of Belarus and outside it.”

By outlining credentialing as a system providing privileges for journalists, Belarus’ accreditation structure is contrary to international standards. The law allows public authorities to choose who covers them by approving or refusing accreditation. It also denies accreditation to journalists who do not work for recognised media outlets. Even journalists who report for foreign outlets must be full-time employees to be able to be accredited by the Belarusian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In practice, the law blocks freelance journalists or independent media outlets from covering the activities of the government and makes accreditation a requisite for a career in journalism. Only journalists who work for state-run outlets are accredited to report on state ministries, parliament or local governments.

Though refusing accreditation does not mean a total ban on a journalist’s professional activities, it creates obstacles to access to information. This discriminatory structure is especially acute for freelance journalists and those who work for independent media outlets.

In May 2016, the local government of Baranavichy district, in the Brest region, refused to accredit Julia Ivashka, a reporter for independent newspaper Intex-press. An official letter said the local government does not intend to expand the list of media outlets which are permitted to cover its sessions. The three currently accredited are state-run.

Under the mass media law, freelance journalists who do not have a contract with an outlet have no legal right to ask for accreditation. At the same time these independent reporters do not enjoy the same rights as journalists who work for accredited media outlets, they can also be targeted by the police, who use the lack of accreditation as a pretext to block freelancers from exercising their professional duties.

On 24 June 2016, police officers prevented independent journalists Yuliya Labanava and Ales Lyubyanchuk from filming a public discussion on the planned construction of a new Minsk shopping mall. Police officers then threatened to remove them from the room altogether if they asked any questions.

On 13 May 2016, the ministry of information refused to accredit а correspondent and cameraperson working for BelaPAN – the main independent news agency in the country – at the XI Belarusian International Media Forum in Minsk. This decision prevented BelaPAN from covering the event. The Ministry of Information did not comment on the reasons for the rejection.

Since April 2015, when Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project began monitoring threats to media freedom in the country, there have been 28 verified incidents involving blocked access that took place in Belarus. Most of these reports involved freelance or full-time journalists working for independent news outlets, who lack accreditation.

“Belarus’ strictly controlled media environment is part of the government’s overall control of the press and information. The number of reported incidents seems low until you consider that Belarus is one of the most restricted countries in Europe, as it’s considered the continent’s ‘last dictatorship’. This arbitrary and capricious accreditation system must be reformed,” Hannah Machlin, Mapping Media Freedom project officer at Index, said.

In 2014 OSCE representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović called on Belarusian authorities to repeal accreditation requirements for foreign and national journalists. “Accreditation should not be a license to work and the lack of it should not restrict journalists in their ability to work and express themselves freely,” Mijatović said.

In the same year the UN Human Rights Committee considered the case of Maryna Koktysh, a journalist working for the independent newspaper Narodnaya Volya. Koktysh was denied accreditation to the House of Representatives of the National Assembly, the lower chamber of the Belarusian parliament. The UN concluded that by creating obstacles to obtaining information, the government violated Koktysh’s right to free expression and recommended a review of Belarusian legislation to prevent similar violations in the future.

10 Aug 16 | Academic Freedom, Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

The stream may be small right now, a trickle, but it is unmistakable. Turkey’s academics and secular elite are quietly and slowly making their way for the exits.

Some months ago, in the age before Turkey’s post-coup crushing of academia, a respected university lecturer told me she was seeking happiness outside Turkey. She was teaching economics at one of Istanbul’s major universities, but neither her nor her husband, who is also in the financial sector, had a desire to remain in the country any longer. They simply packed up and left for Canada.

The growing unease about the future is now accelerating among the academics and mainly secular elite in the country. This well-educated section of society is feeling the pressure more than any other, and as the instability mounts the urge to join the “brain drain” will only increase.

Some of them, particularly those academics who have been fired and those who now face judicial charges for signing a petition calling for a return to peace negotiations with the Kurdish PKK, no longer see a future for their careers. With the government further empowered by emergency rule decrees, the space for debate and unfettered learning is shrinking.

One of the petition’s signatories, the outspoken sociologist Dr Nil Mutluer, has already moved to a role at the well-respected Humboldt University in Berlin to teach in a programme devoted to scholars at risk.

You only have to look at the numbers to realise why more are likely to follow in the footsteps of those who have already left Turkey. In the days after the failed coup that struck at the country’s imperfect democracy, the government of president Recep Tayyip Erdogan swept 1,577 university deans from their posts. Academics who were travelling abroad were ordered to return to the country, while others were told they could not travel to conferences for the foreseeable future. Some foreign students have even been sent home. The pre-university educational system has been hit particularly hard: the education ministry axed 20,000 employees and 21,000 teachers working at private schools had their teaching licenses revoked.

Anyone with even the whiff of a connection to FETO — the Erdogan administration’s stalking horse for the parallel government supposedly backed by the Gulenist movement — is in the crosshairs. Journalists, professors, poets and independent thinkers who dare question the prevailing narrative dictated by the Justice and Development Party will hear a knock at the door.

It appears that the casualty of the coup will be the ability to debate, interrogate and speak about competing ideas. That’s the heart of academic freedom. The coup and the president’s reaction to it have ripped it from Turkey’s chest.

But it’s not just the academics who are starting to go. The secular elite and people of Kurdish descent that are also likely to vote with their feet.

Signs are, that those who are exposed to, or perceive, pressure, are already doing this. Scandinavian countries have noted an increase in the exodus of the Turkish citizens. Deutsche Welle’s Turkish news site reported that 1719 people sought asylum in Germany in the first half of this year. This number already equals the total of Turkish asylum seekers who registered during the whole of 2015. Not surprisingly, 1510 of applications in 2016 came from Kurds, who are under acute pressure from the government.

The secular (upper) middle class is also showing signs of moving out. The economic daily Dünya reported on Monday that the number of inquiries into purchasing homes abroad grew four-to-five times the pre-coup level. Many real estate agencies, the paper reported, are expanding their staff to meet the demand. Murat Uzun, representing Proje Beyaz firm, told Dünya:

“The demand is growing since July 15 by every day. Emergency rule has also pushed up the trend. These people are trying to buy a life abroad. Ten to twelve people visit our office every day….Many ask about the citizenship issues.”

Adnan Bozbey, of Coldwell Banker, told the paper that people were asking him: “Is Turkey becoming a Middle Eastern country?”

According to Dünya, the USA, Ireland, Portugal, Greece, Malta and Baltic countries are popular among those who want to seek life prospects elsewhere.

In short, the unrest is spreading. Unless the dust settles and the immense political maneuvering about the course Turkey is on reverses, it would be realistic to presume that a significant demographic shift will take place in the near future.

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

10 Aug 16 | Bangladesh, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

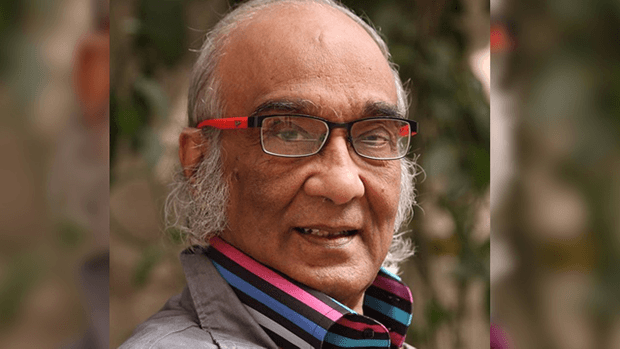

Shafik Rehman (Photo: Reprieve)

Anisul Huq

Minister for Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs

Government of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Secretariat, Building No. 4 (7th Floor) Dhaka-100

4 August 2016

Dear Mr Huq,

We are writing to you as international press freedom, freedom of expression and media advocacy groups about the ongoing detention of Shafik Rehman, an elderly journalist in custody in Dhaka, to set out several serious concerns about his treatment.

We were pleased to note that on Sunday 17 July 2016 the Supreme Court granted Mr Rehman’s request for leave to appeal his detention.

Detention without charge

Mr Rehman was arrested on 16 April 2016 and denied bail by the High Court on 7 June 2016. After more than three months in detention, he has still not been charged with any crime.

He is being investigated by the Bangladesh Detective Branch, who entered his house without a warrant, inexplicably posing as a camera crew, on the day of his arrest.

The detectives missed a deadline on 16 June 2016 to submit a report to Metropolitan Magistrate SM Masud Zaman in Dhaka outlining the alleged case against Mr Rehman. The court extended the deadline until 26 July 2016, despite the fact that the First Information Report in this case was initially filed in August 2015 and the investigation period in the case has expired. On 26 July 2016, the police once again missed the deadline to submit their investigation report and a further deadline has now been set for 30 August 2016 – more than 100 days after his arrest.

Under international law, the Bangladesh authorities have a duty to promptly inform Mr Rehman of the nature of the case against him and either charge or release him. The delays in this case suggest that there is no evidence against Mr Rehman, and that he should be released.

Journalistic career

Mr Rehman is a professional journalist who has spent a lifetime working for freedom of expression. We are concerned that his arrest represents an attack on press freedoms and forms part of a worrying trend in Bangladesh. At the time of his arrest, Mr Rehman was editor of the popular monthly magazine Mouchake Dhil, with experience as a TV host and producer. Previously, he has worked for the BBC and edited Jai Jai Din, a mass- circulation Bengali daily.

The arrest of journalists like Mr Rehman raises concerns about the state of press freedoms in Bangladesh, where several prominent editors have been arrested in recent years.

Denied bail

Mr Rehman is an elderly man in poor health. He spent the first weeks of detention in solitary confinement, without a bed. His health deteriorated and he was rushed to hospital.

His family are seriously concerned about his health failing in prison, and he has missed important medical appointments while on remand.

There are therefore strong compassionate grounds for releasing Mr Rehman on bail, while any evidence (if there is any at all) can be gathered without jeopardising his health.

We hope that Mr Rehman’s appeal will be an opportunity for the Court to take stock of the serious concerns about the case against Mr Rehman and about his health and well-being while he remains in custody.

We appreciate you hearing our concerns and are grateful for swift action to guarantee Mr Rehman’s prompt release.

Yours sincerely,

Reprieve | Index on Censorship | International Federation of Journalists | Reporters Without Borders | Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech | Afghanistan Journalists Center | Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain | Bahrain Center for Human Rights | Canadian Journalists for Free Expression | Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility | Foro de Periodismo Argentino | Free Media Movement | Independent Journalism Center – Moldova | Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information | International Press Institute | Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance | Media Foundation for West Africa | National Union of Somali Journalists | Norwegian PEN | Pacific Freedom Forum | Pacific Islands News Association | Pakistan Press Foundation | Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA | PEN American Center | Public Association “Journalists” | Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

Via post to:

High Commission for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh

28 Queen’s Gate

London

SW7 5JA

09 Aug 16 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Selina Doğan

“Turkish police have cancelled all the journalists’ passports since July 15.”

This tweet landed in my timeline on Monday morning. The author was Selina Doğan, an opposition deputy and a lawyer.

Doğan, who belongs to Istanbul’s Armenian community, tweeted a follow-up on the case of my colleague, Hayko Bağdat, whose passport was seized at the border as he returned to Turkey.

I spoke to Doğan about the situation. She and her husband, lawyer Erdal Doğan, had insisted on knowing what really is going on with what they see as arbitrary restrictions on freedom of movement. She told me that “as a precaution” an unknown number of journalists’ passports were “cancelled”. A police officer told her that according to a government decree the police had to seize travel documents before sorting out who is under legal inquiry. Anyone “suspected” would have their travel documents taken away. “It is even more bizarre now,” she told me. “Each and every person is a priori suspect, and has to prove their innocence, instead of vice versa.”

Soon after my chat, another tweet: this time it was Eren Keskin, a well-known Kurdish columnist and lawyer, who is also co-editor in chief of pro-Kurdish daily, Özgür Gündem. “Everybody under the legal inquiry under Anti-Terror Law should check,” she wrote. “Thousands of passes cancelled. I had already a ban on travel abroad, now my pass cancelled. Thanks Turkey, I am a fan of your democracy :).”

What about a journalist who is now charged with lifetime imprisonment stemming from a single news report? Şermin Soydan, a Kurdish reporter, is just such a case. Soydan, who is with the pro-Kurdish DIHA news agency, was arrested 14 May for a story she wrote titled The Secret Document on Operation to Gever, which details the security operations in Yüksekova, in Hakkari province. The 21-page indictment, calling her story “so-called news”, now accuses her of “obtaining state secrets on security”, “jeopardising security forces’ abilities to combat”, “membership of a terrorist organisation” and “aiding and abetting a terror group”.

Out of 77 journalists affiliated with DİHA in total, 13 are in jail.

Meanwhile, the discontent of the opposition parties with the government’s emergency rule decrees is growing. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has issued three very restrictive decrees and, according to the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), is blocking debates in parliament. The Turkish constitution spells out that under emergency rule decrees must be debated by parliament within 30 days of the issue. Some sources from the CHP told daily Cumhuriyet that they see clear signs from the AKP that it will call for a long recess of parliament, and, at best, a debate will take place in early October.

Given the militant language used by the AKP in Sunday’s mass rally in Istanbul and the growing concerns over the legislative body being paralysed, there is strong reason to remain skeptical about the sequences of events in Turkey.

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.