29 Jul 16 | mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Arda Akin (Hürriyet)

The latest journalist arrested in Turkey is Arda Akın, a young reporter with the Hürriyet daily, part of the “mainstream” Doğan Media Group. Arda was in the “first” arrest list, issued on Monday, which mainly consisted of investigative reporters. In May, he was among those who won the European Union Investigative Journalism Award 2016, a prestigious prize delivered every year in six Balkan countries and Turkey. In his award-winning article, Akın told of corruption related to ruling Justice and Development Party figures.

Akın now joins 40 journalists taken into custody since the night of the bloody 15 July coup attempt. The arrests, in particular well-known veteran journalists such as Nazlı Ilıcak and Prof Şahin Alpay, adds to the profound concerns for press freedom in Turkey, where emergency rule gives the authorities power to extend arrest periods up to 30 days.

Former Swedish foreign minister Carl Bildt, who has known Alpay for many years, tweeted on Wednesday:

Meanwhile, a series of sanctions launched by the government ratchets up the worries to new levels. In an emergency decree, a large number of media outlets were shut down; their assets are to be expropriated by the government.

It’s a long list, encompassing 45 newspapers, 16 TV channels, 15 radio stations, three news agencies, 15 periodicals and 29 publishing houses. Some of these outlets were raided and allowed to continue under a trusteeship regime, but it seems apparent that they will be discontinued, with a large number of journalists joining the unemployed. In this context, we are witnessing the ruin of the Turkish media. Emergency rule means massive self-censorship within the existing conglomerate media with a block on critical reporting.

The mass closure targets those outlets allegedly affiliated with the Gülenists. But two questions arise immediately …

Why does the government not completely focus on the culprits who were part of the coup attempt and instead give priority to targeting journalists? We all know that, as long as it is not preaching violence or becoming part of it, journalism is not a crime. If there are journalists who are actively involved in plotting and execution of a coup — a very serious crime — they should, of course, be put on trial. Silencing a large bulk of the media simply places a frosted glass on this aspect, awakening fears that the other segments of the media — for example the Kurdish press — could be next.

Second, with less room for reporting and analysis, it will be more and more difficult to inform the public about the truth behind the coup attempt and the delicate situation Turkey is in. As expected, everything is now open to disinformation and the manipulation of facts.

In general terms, the decree curbing the media, as well as dismissing almost half of the top military brass, has very restrictive aspects. It is about the enhanced authority given to judges and prosecutors. It gives them powers to execute searches in houses and offices. The most serious part is that even defence lawyers’ offices will not be immune from raids and searches. For wiretapping, a ruling from the judge will not be necessary; it will all be up to the jurisdiction of the prosecutors.

With the decrees coming in, Turkey now enters an even more precarious period. Much will depend on whether or not the democratically elected opposition will act in unison, and manage to push for a return to normalisation. Tough times are ahead.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

29 Jul 16 | Bosnia, Europe and Central Asia, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Poland, Turkey, United Kingdom

Click on the dots for more information on the incidents.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Turkey: Warrants issued for arrest of 89 journalists

Turkish authorities have issued two lists of journalists to be arrested since the 15 July failed military coup attempt in the country. Firstly, on 25 July, authorities issued the names of 42 journalists as part of an inquiry into the coup attempt. Well-known commentator and former parliamentarian Nazli Ilicak was among those for whom a warrant was issued, as was Ercan Gun, the head of news department at Fox TV in Turkey.

Two days later, 27 July, authorities issued warrants for the detention of 47 former executives or senior journalists of the newspaper Zaman. The arrests were part of a large-scale crackdown on suspected supporters of US-based Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen, accused by Ankara of masterminding the failed coup. The authorities shut down Zaman in March. At least one journalist, former Zaman columnist Şahin Alpay, was detained at his home early on Wednesday.

26 July, 2016 – Media Print Macedonia, the publisher of several daily and weekly newspapers, announced that it would dismiss 20 staff members, mostly experienced journalists and former editors from the daily Vest.

Layoffs are also to include employees from daily Utrinski Vesnik, Dnevnik, Makedonski Sport and weekly magazine Tea Moderna.

MPM stated layoffs were prompted by bad results and that the decision on who to dismiss would be based on the company’s internal procedures. Employees who lose heir jobs are to be compensated from one up to five average salaries, TV Nova reported.

24 July, 2016 – Emir Talirevic, a doctor who owns Moja Klinika, a private healthcare institution in Sarajevo, used Facebook to insult Selma Ucanbarlic, a journalist for the Centre for Investigative Journalism, following her articles about Moja Klinika, regional TV outlet N1 reported.

On 24 July Talirevic wrote on Facebook, among other things, that “judging by her psycho-physical attributes [the journalist] should never be allowed to do more complex work than grilling a barbecue”. He alleged hers were “imbecilic findings”, adding that “her work requires higher IQ than 65”.

In a second post, published on 27 July, Talirevic wrote that “as the toilet tank is taking away my associations on Selma and her CIN(ical) website I am thinking about the oldest profession in the world – prostitution”. He also wrote: “CIN is financed by gifts, like prostitutes”, and “after today’s article at least we know for whom Selma Ucanbarlic and her CIN colleagues are spreading their legs”.

22 July, 2016 – Masza Makarowa, a former journalist for the Russian language division of national broadcaster Polskie Radio, left the station due to a repressive climate and censorship, she claimed on her Facebook page.

An “atmosphere of scare tactics and paranoia” was prevalent at the broadcaster, Makarowa said. She also claimed that the station management instructed staff on which sources to consider for publication to Russian-speaking audiences, approving right-leaning, pro-governmental websites while explicitly prohibiting liberal sources like Gazeta Wyborcza for being opinionated. Certain updates, furthermore, were removed from the website.

22 June, 2016 – Jeff Howell, who had been writing a home maintenance advice column for The Telegraph for 17 years, was allegedly dismissed and removed from the Telegraph website after comments he made to his property section editor, Anna White.

According to Private Eye, the column, which was initially published both on the website and online, was removed from the website after he made a joke to property section editor White about correcting the Telegraph’s editing errors following a typo in January. Much of the column’s online archive was deleted following the incident.

Howell’s page on the Telegraph website used to get up to 10,000 hits daily but the removal of most of his columns from the website “made it easy to justify his dismissal by saying he didn’t produce any online traffic”.

29 Jul 16 | Academic Freedom, Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Turkey

People gather in solidarity with the press outside Zaman newspaper in Istanbul in March 2016

By Ianka Bhatia and Sean Vannata

The spotlight has been on Turkey following the attempted coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the government’s ensuing crackdown on journalists, teachers, judges and soldiers. How did it come to this? Here are five key articles on Turkey from Index on Censorship showing the escalation of threats to freedom of expression prior to July’s failed coup.

1. Silence on campus

Early in 2015, an academic at Ankara University’s political sciences department spent an evening writing questions for an exam. He never for one minute suspected that one of those questions might lead to death threats. Index’s Turkey editor Kaya Genç reported on the struggle for academic freedom in Turkey’s election year for the summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

2. “Judicial coup” sends clear warning to Turkey’s remaining independent journalists

“Nothing could illustrate the course of developments in Turkey better than the case of prosecutor Murat Aydın,” Yavuz Baydar wrote for Index on 8 June 2016. “In what was described as a ‘judicial coup’ in critical media, Aydin was one of 3,746 judges and prosecutors, who were reassigned in recent days, an unprecedented move that has shaken the basis of the justice system. Some were demoted by being sent into internal “exile”, some were promoted.”

3. Turkey war on journalists rages on

The ongoing deterioration in Turkey’s press freedom has been well documented by Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project since its launch in 2014. Back in March 2015, Index’s assistant online editor Ryan McChrystal looked at how, with journalists being killed, detained and prevented from working, the crackdown on Turkey’s media only appears to be getting worse.

4. Interviews with Turkey’s struggling investigative reporters

Kaya Genç interviews writers from the acclaimed independent newspaper Radikal about its closure and the shape of Turkish investigative journalism today for the summer 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

5. Turkey’s film festivals face a narrowing space for expression

The Siyah Bant initiative, which carries out research on censorship of the arts in Turkey, has given much coverage to obstacles to freedom of expression in the cinematic field in research published in recent years. In June 2016, Index published a report on cases of censorship at Turkish film festivals.

28 Jul 16 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

Nazeeha Saeed has been arbitrarily curtailed by Bahrain’s Information Affairs Authority.

We, the undersigned, express our deep concern with the Bahraini Public Prosecution’s decision to charge Nazeeha Saeed, correspondent for Radio Monte Carlo Doualiya and France24, with unlawfully working for international media. We consider this an undue reprisal against her as a journalist and call on Bahrain’s authorities to respect fully the right of journalists to practice their profession freely.

Nazeeha Saeed is an award-winning journalist and correspondent for Radio Monte Carlo Doualiya and France24. She has previously reported on the protest movement in 2011, and has reported on the mounting dissent against the Bahraini government for the last several years.

On Sunday 17 July 2016, the Public Prosecution summoned Nazeeha Saeed for interrogation based on a legal complaint from the Information Affairs Authority (IAA). The prosecution charged her under article 88 of Law 47/2002, which regulates the press, printing and publication. Article 88 states that no Bahraini can work for foreign media outlets without first obtaining a license from the Information Affairs Authority (IAA), which must be renewed annually.

Prior to the expiration of her license, Nazeeha Saeed applied for a new one at the end of March 2016, at which point, the IAA refused a renewal. This is the first time she has received such a rejection. Following this, Saeed continued to work as a correspondent for France24 and Radio Monte Carlo Doualiya. She now faces trial in the civil courts and a fine of up to 1000 Bahraini Dinars (USD $2650) if found guilty.

This is not the first time Nazeeha Saeed has been subjected to harassment by the Bahraini authorities. In May 2011, during a state of emergency imposed in response to Arab Spring protests, police summoned Saeed to the station and detained her there. For her coverage of events in Bahrain – Nazeeha Saeed witnessed police killing a man at a protest and rejected the government narrative of events – police allegedly subjected her to hours of torture, ill-treatment and humiliation, which only ended when she signed a document placed before her. She was not allowed to read it. Despite complaining to the Ministry of Interior and the new Special Investigations Unit, the body under the Public Prosecution charged with investigating claims of torture and abuse, in November 2015 the authorities decided against prosecuting the responsible officers on the basis of there being insufficient evidence.

In June 2016, Bahrain’s authorities placed Nazeeha Saeed on a travel ban, preventing her from leaving the country. The ban was applied without informing Saeed, who only discovered it after she was refused boarding on her flight. The police officer at the airport was unable to explain the reason for this travel ban, and officials from the immigration department, the public prosecution and the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), told the journalist that they were not even aware of its existence. Saeed is one of approximately twenty individuals known to have been banned from travel in Bahrain since the beginning of June 2016. Other journalists working for international media face similar threats and have also reported facing increased pressure from the government in the last year, making their work difficult. RSF and the Committee to Protect Journalists both list Bahrain as one of the leading jailers of journalists in the world. One of them, Sayed Ahmed Al-Mousawi, was stripped of his citizenship by a court in November 2015.

As organisations concerned with the right to freedom of expression, we call on the Government of Bahrain to end the reprisals against Nazeeha Saeed, lift her travel ban and drop the charges against her. We also call on the authorities to stop arbitrarily withholding license renewals and to allow journalists to report with full freedom of expression as protected under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Signed,

Adil Soz, International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

ACAT

Albanian Media Institute

Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy

Bahrain Press Association

Bytes for All

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Cartoonists Rights Network International

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Committee to Protect Journalists

Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

English PEN

European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

Freedom Forum

Freedom House

Free Media Movement

Front Line Defenders

Gulf Centre for Human Rights

Hisham Al Miraat, Founder, Moroccan Digital Rights Association

Human Rights Network for Journalists – Uganda

Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

Index on Censorship

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

Instituto de Prensa y Libertad de Expresión – IPLEX

International Press Institute

Justice Human Rights Organization

Maharat Foundation

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Watch

Norwegian PEN

Pacific Islands News Association

Pakistan Press Foundation

Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders

Social Media Exchange – SMEX

Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

28 Jul 16 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Şahin Alpay is a columnist for multiple newspapers, including Yarina Bakis, which was forced to suspend its print edition after the coup.

It was 6am when Professor Şahin Alpay and his wife heard the knock at the door. It was the police. They had come to take him into custody.

The 72-year-old journalist’s flat was searched for two hours. As he was led away, Alpay said: “I do not know why I am being taken away. I am not in a position to say anything.”

Alpay was only one of 47 journalists who were subject to arrest under warrants issued on Wednesday. The list included the names of columnists, editors and reporters who formerly had been employed in Zaman daily, which was seized by the security forces last March. It and its journalists now stand accused of being the so-called media leg of Fethullah Gülen terror organisation.

Alpay has been one of the most consistent and powerful socially liberal voices in Turkey for decades. He is very well known in European political circles, particularly in Sweden where he had completed his doctorate. He is respected within Germany’s social democratic, liberal and green movements. For years, he had been part of democracy projects conducted by the Ebert and Naumann foundations. Until very recently he had taught political science at Bahçeşehir University and continued to write columns in multiple newspapers.

The list also includes names such as Hilmi Yavuz, an 80-year-old poet, philosopher and literary critic, who is also well known abroad. Other names on the list wereP rofessor İhsan Dağı, a brilliant liberal scholar, and theologue Ali Bulaç.

Then there are journalists: Lale Kemal, an outstanding analyst of defence issues for Jane’s Defence Weekly; Nuriye Akman, who is well known for her long interviews; Bülent Keneş, former editor-in-chief of Today’s Zaman, which is now controlled by trustees appointed by the government. The list goes on and on.

On Monday, a list of arrest warrants issued against 42 journalists. On Wednesday there were 47 more names. With this second wave of arrests, there seems no doubt that the clampdown on critical and independent journalism will continue in stages. The first wave targeted reporters regardless of the publications they were affiliated with. The second wave was aimed at Zaman. The message shared on social media: there is more to come.

Turkey’s situation cannot be any more serious. The aftermath of the completely unacceptable and bloody coup is marked by an incomprehensible priority to target dissenting intellectuals. This is reminiscent of the pattern the generals set down after the military coup in 1980. The targets were communists then, now it’s Gülenists that are the subject of the massive witch hunt.

The accusation directed at Nazlı Ilıcak, a 71-year-old veteran journalist on the centre right-liberal flank, is rather telling. The lawyers say that she is to be charged with “establishing the media leg of FETO terror organisation”, meaning a lifetime imprisonment if the charge sticks.

This was the overall picture as of the past 24 hours. It is, then, completely appropriate that, now that the witch hunt is openly targeting liberals on the right and left in Turkey, the rules of the emergency rule paves the way for a counter-putsch or, as the veteran journalist, Hasan Cemal, a close friend of Alpay and Ilıcak, labelled as “civilian coup”.

Indeed, Wednesday morning Human Rights Watch was swift in issuing an SOS warning to the world about the emergency rule, which now allows the authorities to keep people in custody up to 30 days.

“It is an unvarnished move for an arbitrary, mass, and permanent purge of the civil service, prosecutors, and judges, and to close down private institutions and associations without evidence, justification, or due process,” HRW said.

“The wording of the decree is vague and open-ended, permitting the firing of any public official conveniently alleged to be ‘in contact’ with members of ‘terrorist organizations’, but with no need for an investigation to offer any evidence in support of it,” Emma Sinclair-Webb said. “The decree can be used to target any opponent – perceived or real – beyond those in the Gülen movement.”

This is the list of 47 journalists targeted for arrest:

Osman Nuri Öztürk, Ali Akbulut, Bülent Keneş, Mehmet Kamış, Hüseyin Döğme, Süleyman Sargın, Veysel Ayhan, Şeref Yılmaz, Mehmet Akif Afşar, Ahmet Metin Sekizkardeş, Alaattin Güner, Faruk Kardıç, Metin Tamer Gökçeoğlu, Faruk Akkan, Mümtaz’er Türköne, Şahin Alpay, Sevgi Akarçeşme, Ali Ünal, Mustafa Ünal, Zeki Önal, Hilmi Yavuz, Ahmet Turan Alkan, Lalezar Sarıibrahimoğlu (Lale Kemal), Ali Bulaç, Bülent Korucu, İhsan Duran Dağı, Nuriye Ural (Akman), Hamit Çiçek, Adil Gülçek, Hamit Bilici, Şenol Kahraman, Melih Kılıç, Nevzat Güner, Mehmet Özdemir, Fevzi Yazıcı, Sedat Yetişkin, Oktay Vızvız, Abdullah Katırcıoğlu, Behçet Akyar, Murat Avcıoğlu, Yüksel Durgut, Zafer Özsoy, Cuma Kaya, Hakan Taşdelen, Osman Nuri Arslan, Ömer Karakaş.

A version of this article was originally posted to Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is published here with permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

28 Jul 16 | mobile, News and features, Turkey

Büşra Erdal, one of 89 journalists subject to arrest, surrendered in Manisa and was taken to police headquarters in handcuffs.

Media freedom must be treated for what it really is: a strong test of democracy. And any response to a crisis requires a cautious approach if basic civil liberties, the building blocks of any free society, are to be protected. Make no mistake about it, in the case of Turkey, we are faced with a situation where authorities are violating the basic human right of Turkish citizens to engage in free media.

Just consider the following media freedom issues that have taken place after the attempted coup in Turkey on 15 July.

- The authorities have ordered the closure of 45 newspapers, 15 magazines, 16 television channels, 23 radio stations, 3 news agencies, and 29 publishers;

- Arrest warrants have been issued against 89 journalists, accusing them of supporting terrorism; seven of them have already been detained;

- 370 journalists at the state broadcaster TRT have been suspended;

- Press accreditations for 34 journalists from eight other Turkish media outlets have been revoked;

- 60 staff members with Cihan News Agency have been fired;

- The Radio and Television Supreme Council of Turkey (RTÜK) has cancelled the licenses of more than 20 radio and television stations;

- The Telecommunications Authority (TIB) has blocked more than 20 news websites.

These issues must also be put in the context of the general, sharply deteriorating media freedom situation in Turkey in the past few years. An anti-terror law in Turkey, in effect since 1991, is being used to round up terrorists but also many others, including those who it is my job to lobby for – journalists and media.

Today there are dozens of journalists in jail in Turkey, prosecuted and convicted mostly under a law designed to fight terrorism and protect people. The number of journalists jailed in Turkey is without precedent in the OSCE region. Under the anti-terror law, merely reporting on controversial topics could land a journalist in court.

The latest case in a string of the recent crackdown activities on media in Turkey is the detention of seven journalists in the last two days, while arrest warrants were issued against several dozens more, accusing them of supporting terrorism. To say that dissenting voices, although still present and persisting, are under duress in Turkey is a severe understatement.

The authorities’ systematic abuse of media and its players, done with the intention of guaranteeing control of the media landscape, is nothing short of a clear and present threat to democracy in the country.

Media-freedom advocates like myself, must and will continue to raise our voices and provide the defenses necessary for free expression and free media to flourish in Turkey.

I will raise the issue of the rights of media and of journalists before national legislatures. I will engage in public awareness campaigns on behalf of free media. I will continue to do everything in my power to protect and safeguard the independent and pluralistic voices that are the cornerstones of any society. And I will call on elected officials to spend the resources, including political capital, essential to build environments conducive to free expression.

I believe that a society that respects human rights is working towards the common good of its people and that limiting and breaching fundamental democratic and civil liberties negatively affects the common good. I also believe that the role of elected officials is to write good laws and appoint good law enforcement authorities, including police, prosecutors and judges to interpret those laws in a manner that will make free expression possible.

All democratically elected governments must adhere to the underlying rules of their society – free markets, universal suffrage, access to government information and other basic civil liberties, including a free and pluralistic media environment.

Freedom of expression is a universal and basic human right; it does not stop at views deemed appropriate by the authorities. It remains the role of journalists to inform people of public issues, including highly sensitive issues. And it remains the role of the authorities to ensure that journalists, no matter how critical or provocative, can do so freely and safely. Turkey fails on this account.

More commentary from Dunja Mijatović

Why quality public service media has not caught on in transition societies

Chronicling infringements on internet freedom is a necessary task

Propaganda is ugly scar on face of modern journalism

More about Turkey

Yavuz Baydar: Erdogan is ruling Turkey by decree

Can Dündar: Turkey is “the biggest prison for journalists in the world”

Turkey’s film festivals face a narrowing space for expression

27 Jul 16 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Büşra Erdal, who surrendered in Manisa, taken to police headquarters in handcuffs.

“It was very, very close,” according to a source who followed the case of columnist and human rights lawyer Orhan Kemal Cengiz. By a hair he had avoided detention. While Cengiz has now been released, he is unable to travel abroad.

During the interrogation, Cengiz had repeatedly been asked about critical tweets he had posted about a year ago. “Those who led the interrogation were utterly hostile, seemingly set for finding a pretext to hold him in custody,” my source said. Cengiz’s friends believe that his impeccable international reputation and his work for the European Court of Human Rights, where he has defended Kurds and even, in a couple of cases, Turkish Islamists against the state, may have saved him from a jail cell.

However, there is nothing to suggest the easing this post-coup witch hunt. Yesterday, the veteran journalist Nazlı Ilıcak was arrested at a police checkpoint in Bodrum and taken into custody. Judicial affairs journalist Büşra Erdal surrendered after she tweeted that she was being punished for her work. Sadly the powerful Doğan Media Group outlets, of which both honourable journalists are affiliated, remained silent. Not a word of support was seen in any of the group’s newspapers.

The only support came from the Enis Berberoğlu, former chief editor at Hürriyet and now MP and deputy of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), who tweeted: “As their superior once, I was mainly responsible for the stories and the sections that Bülent Mumay and Arda Akın wrote and worked for. I vouch and stand for them.”

Against the backdrop of the authorities’ search for 42 journalists, pro-government media was busy on Tuesday inciting hatred for the columnists and asking for their imprisonment, including the daily Akşam. The pro-Justice and Development Party (AKP) daily Sabah added to the flames by accusing columnists such as Hasan Cemal, Kadri Gürsel, Cengiz Çandar, Perihan Mağden, Mehmet Altan and others of provoking the coup. These journalists and columnists are no longer allowed to express themselves in any media outlet.

Perhaps more than anything else, it was a crucial legal appointment that worried Turkey’s dissident figures in media and academia. In a hasty move, the government named İrfan Fidan as the chief prosecutor for Istanbul. Until Monday, Fidan was a deputy attorney in Istanbul’s Anti-Terror and Organised Crime Unit. What’s most notable, however, is that Fidan was the prosecutor who sentenced Cumhuriyet editors Erdem Gül and Can Dündar to five years and five years and ten months, respectively, in prison. The pair had covered the alleged supply of arms to Syrian jihadist groups by the Turkish secret service.

Academic Esra Mungan and three others who had signed the peace petition for the Kurds clashed were also detained due to his efforts. In another example, Fidan had taken over the case that implicated high-ranking AKP ministers and president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s family members in corruption. He dismissed all charges.

Many fear, therefore, that his appointment to such a powerful post may come to mean a steep escalation against journalists and scholars in the coming weeks.

All other signs, too, indicate harder times.

On Monday night, in the midst of turmoil, Erdogan ratified the law which, in practice, subordinates the high judiciary to the political executive and immediately after the Board of Judges and Prosecutors, led by the Justice Ministry, implemented a long series of appointments and removals in the Court of Cassation and Council of State.

Erdogan met with two opposition party leaders. CHP and Nationalist Movement Party leaders were invited, but not the third largest elected one, the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party. It was a deliberate choice, raising eyebrows on how serious the ruling AKP is about rebuilding democracy. In addition, Erdogan spoke for a possible extension of emergency rule for an additional three months.

Meanwhile, Turkey will be run by decrees and everybody knows what that means.

A version of this article was originally posted to Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is published here with permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

26 Jul 16 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Ukraine

Pavel Sheremet (Photo: Ukrainska Pravda)

The death of Pavel Sheremet on Wednesday 20 July is the latest and most egregious example of violence against journalists in Ukraine, according to verified incidents reported to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project.

Sheremet was killed when the car he was driving exploded on the morning of 20 July in Kyiv. In a statement, Ukrainian police said that an explosive device detonated at 7.45am as Sheremet was driving to host a morning programme on Radio Vesti, where he had been working since 2015.

The car belonged to Sheremet’s partner, journalist Olena Prytula, who co-founded Ukrainska Pravda with murdered journalist Georgiy Gongadze.

Sheremet had been imprisoned by Belarusian authorities in 1997 for three months before being deported to Russia. Though stripped of his citizenship in 2010, he continued to report on Belarus on his personal website. He moved to the Ukrainian capital in 2011 to work for the newspaper Ukrainska Pravda.

A review of Mapping Media Freedom data from 1 January to 20 July found 41 attacks on journalists — including physical violence, injuries and seizure or damage to equipment and property of journalists — have taken place in Ukraine since the beginning of the year. The largest number of incidents – about one-third – occurred in Kyiv. More than half of these journalists were attacked by unknown assailants, while the names of perpetrators in a third of these incidents are known. In about one in three cases, the attacks were committed by representatives of local authorities.

While impunity remains a key issue in Ukraine contributing to violence against journalists, the situation is slowly beginning to change for the better compared to previous years. According to the Institute of Mass Information, a positive trend has been spotted since the beginning of the year: There has been a slight increase in the number of cases involving violation of the journalists’ rights submitted to courts. In particular, there were 11 such cases in 2015. Meanwhile, 12 such cases were submitted to court for the first quarter of 2016 alone.

Despite the improvement in prosecutions, journalists are continuing to be subject to violence and intimidation.

In June, a series of incidents occurred in Berdiansk in the Zaporizhzhia region.

On 10 June Volodymyr Holovaty, a journalist working for Yuh TV, and his cameraman, Anatoliy Kyrylenko, were physically assaulted at a recreation center in Berdiansk Spit. A group of people in camouflage set upon them without warning. The attackers swore, demanded that filming stop, took the camera, stole a data storage device and struck the journalist and the cameraman, who were taken to a hospital.

On 7 June, during a rally at the Berdiansk courthouse, an unknown person harassed cameraman Bohdan Ivanuschenko and journalist Volodymyr Dyominof, who both work for Yuh TV. In that incident the individual interfered with their filming of a report with obscene language and threatened the media professionals with physical violence.

In response, journalists staged a rally on 13 June to bring attention to the recent threats and assaults in the town and demand a stronger police response. The journalists wrote an open letter demanding prosecutors help protect the rights of media workers in the town.

In May physical attacks took place in Kherson, Kyiv, Mariupol, Mykolayiv, Kharkiv, Marhanet, Zaporizhzhia and Zirne.

In the Kyiv incident, photographer and cameraman Serhiy Morhunov, who covers the conflict in eastern Ukraine, was assaulted on 22 May by unknown assailants. The journalist suffered serious head injuries including a brain haemorrhage, fractured lower jaw and partial memory loss. The doctors described his condition as serious. Morhunov was not robbed during the attack.

In Zaporizhzhia Anatoliy Ostapenko, a journalist working for Hromadske TV, who reported on corruption allegedly involving regional officials, was assaulted by masked individuals on 24 May. The journalist was walking to work when he was cut off by a car with tinted windows and lacking a license plate. Three masked men exited the car, knocked Ostapenko to the ground and physically assaulted him. Ostapenko suffered numerous bruises.

On 25 May, in Kherson, Taras Burda, the husband of a member of the Suvorivsky district council, attacked Serhiy Nikitenko, a journalist for Most media and the representative of NGO Institute of Mass Information in the region, with a tablet computer during an altercation. Burda told IMI that the journalist had attacked him first.

Many attacks have been directed at the property or equipment of journalists. In the village of Lebedivka in the Odesa region, poachers threatened the crew of the Channel 7 investigative programme Normal. The individuals pierced the tires of the journalists’ car by laying spike strips and threw eggs at the vehicles. The incident occurred when the crew was filming a TV report about the activities of poachers in the Tuzla Coastal Lakes national reserve.

On 1 April, in the town of Konotop in the Sumy region, unknown persons threw Molotov cocktails at local TV studio. A similar incident occurred in Kyiv on April 22 when 15 unidentified people attacked the office of the Ukraine TV channel. They poured red paint in the channel’s lobby and left a print out reading “Blood will be spilled!”

In April, several assaults on journalists took place in Kyiv (journalists of 1+1 TV channel were attacked), and in the village of Lymanske in Odesa region.

Only one attack on journalists was recorded in February. However, it was a flagrant incident in the context of physical violence. In Kharkiv, representatives of the Hromadska Varta organisation attacked Stanislav Kolotilov and Lesya Kocherzhuk, journalists for the Kharkiv News portal. Kolotilov suffered a concussion and spinal injury. Kocherzhuk was burned on the hand with a cigarette. The journalists were investigating allegations of illegal construction connected to the Hromadska Varta.

Also in February, representatives of the Azov civil corps blocked the premises of the Inter TV channel. The blockade participants tried to enter the office, threw debris at it and painted the doors black.

In January, journalistic activity was obstructed in Zhytomyr during a conflict involving the Zhytomyrski Lasoshchi confectionery factory. Guards prevented reporters from Channel 5 and UA1 local online media outlet from filming. A microphone was snatched from Channel 5 journalist and a camera was damaged.

Also in January, assaults on journalists, as well as attacks on journalists’ property occurred in Ternopil, Kyiv, Mykolayiv and Odesa, as well as in the village of Dovzhanka in the Ternopil region and the town of Karlivka in the Poltava region.

On 11 January 2016, the windows of a car belonging to journalist Svitlana Kriukova were smashed by unknown perpetrators but nothing was stolen from the vehicle. Kriukova was writing a book on Hennadiy Korban, a politician and businessman said to be close to oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskiy. Korban was under investigation for alleged criminal offences including kidnapping and theft. The incident occurred when the Kriukova was visiting Korban at the hospital and she believes the damages are linked to her professional activities.

25 Jul 16 | mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Nazlı Ilıcak

A “ping” woke me in early hours of Monday morning. It was a message from a colleague reading: “Signs of a crackdown. Arrest warrant for Nazlı Ilıcak is issued, she is being searched.”

This was the witch hunt that many critical journalists who belong to the shrinking independent media dreaded for days.

Ilıcak is a 72-year-old veteran journalist. A fiercely defiant figure who belongs to the centre-right and liberal flank of the media, she had just lost her column in the liberal daily, Özgür Düşünce, which was forced to close last week under immense legal and financial pressure.

I rushed out of bed to contact lawyers pursuing the cases, like the one about Orhan Kemal Cengiz, an internationally respected columnist, lawyer and human rights activist, who was conditionally released on Sunday with a ban on travelling abroad.

Soon we had been informed about a list of 42 journalists who have all been targeted with arrest orders on the basis of being part of the “media leg of terrorist organisation FETO” and by implication part of the Gülen Movement.

Reminiscent of Thomas Hobbes’s aphorism, “homo homini lupus” (“man is wolf to man”), some well-placed journalists were busy – like a certain popular columnist with Hürriyet daily – joining the chorus in support for their arrest.

The manhunt was unleashed early and at the time of writing, at least 19 of them were either seized or had surrendered. Ilıcak’s whereabouts were unknown. Eleven of the journalists on the list are believed to be abroad.

The list is a curious one. For us veteran journalists it contains a blend of good colleagues and bold reporters, who were busy breaking story after story on corruption, abuses of power and the deterioration of Turkey’s democratic order.

Büşra Erdal, who wrote for the now-closed Zaman Daily, was one of the best reporters covering the judiciary and court cases; Cihan Acar was known for relentlessly scrutinising stories in the now shuttered Bugün daily and later in Özgür Düşünce. They were long targeted as Gülen sympathisers but what mattered for journalism was their contribution to it.

Another, Bülent Mumay, was recently fired from Hürriyet. Staunchly secular, he ran the internet edition of the large daily, and it was his endless questioning of the government via Twitter that, he says, led to his unemployment. Perhaps not so surprisingly, he was quick to post a photo of his press card on Facebook, issued by Turkish Journalists’ Association (TGC), saying: “This is the only organisation I belong to. I know of no other; I know of no other profession. I shall now go the prosecutor’s office to tell this.”

Another one was Fatih Yağmur, a brilliant young reporter who was the first to break the story in March 2014 of the Turkish Secret Service lorries that allegedly carried weaponry to Syrian jihadists months before daily the Cumhuriyet, whose editor Can Dündar was sentenced to five years and ten months in prison.

Yağmur was soon after fired from Radikal daily, a part of Doğan Media Group, without any specific explanation.

The Platform for Independent Journalism (P24), of which I am a co-founder, has awarded Yağmur with the European Union Investigative Journalism Award last year. He was proud to be recognised after the humiliation of being left unemployed for doing his job properly.

Soon after the manhunt began, Fatih tweeted: “I hear that arrest order was issued on me. It was obviously not enough to punish me with unemployment. I am now shutting down my telephone etc. I shall not surrender until the Emergency Rule is over.”

We also found out that Ercan Gün, news editor of Rupert Murdoch-owned Fox TV, was on the list. His friends said he was on his way to Istanbul to surrender. Gün tweeted: “I trust the law, even if under Emergency Rule.”

With the traffic of those hunted, it was apparent that they believed a certain motive behind the arrests. Ufuk Şanlı, who had earlier worked with Zaman and after (the now a staunch pro-AKP daily) Sabah, tweeted: “I understand that the arrests were issued about journalists who covered and commented about the graft probes (about Erdoğan and the AKP top echelons) in 17-25 December. Thus, my name too.”

He added: “I’ve been a journalist for 15 years, and unemployed for 10 months. I want everybody to know that I have not been in anything but journalism all this time. I believe in democracy, and please pay attention to anything else [said].”

Indeed, the curious mix about the list is telling: instead of a core of columnists, keen reporters, which is the backbone of journalism, stand out. So, informing part of our profession is automatically dealt another severe blow.

This is now the time to raise the SOS flag to all our good colleagues in democratic countries. Unless given clearly articulated assurances about media freedom, the ongoing crackdown will remain a fact. The entire journalist community and international organisations should be acting with a maximum focus on the developments.

All the independent journalists of Turkey who fear the worst, I’m afraid, are justified to do so.

The 42 journalists targetted with arrest orders are: Abdullah Abdulkadiroğlu, Abdullah Kılıç, Ahmet Dönmez, Ali Akkuş, Arda Akın, Nazlı Ilıcak, Bayram Kaya, Bilal Şahin, Bülent Ceyhan, Bülent Mumay, Bünyamin Köseli, Cemal Azmi Kalyoncu, Cevheri Güven, Cihan Acar, Cuma Ulus, Emre Soncan, Ercan Gün, Erkan Akkuş, Ertuğrul Erbaş, Fatih Akalan, Fatih Yağmur, Habib Güler, Hanım Büşra Erdal, Haşim Söylemez, Hüseyin Aydın, İbrahim Balta, Kamil Maman, Kerim Gün, Levent Kenes, Mahmut Hazar, Mehmet Gündem, Metin Yıkar, Muhammet Fatih Uğur, Mustafa Erkan Acar, Mürsel Genç, Selahattin Sevi, Seyit Kılıç, Turan Görüryılmaz, Ufuk Şanlı, Ufuk Emin Köroğlu, Yakup Sağlam, Yakup Çetin.

But it was not just the press that have reason to fear the aftermath of the coup.

The number of arrests nationawide has approached 15,000 while 70,000 people have been purged within the state apparatus and academia. According to Erdogan’s statement late Saturday night, out of 125 generals arrested, 119 have been detained. The number of lower ranked officers and soldiers rounded up stands at 8,363.

Out of the 2,101 judges and prosecutors arrested, 1,559 are in detention as well as 1,485 police officers and 52 top local governors. Fifteen universities, 35 hospitals, 104 foundations, 1,125 NGOs and 19 trade unions have been shut down, based on the allegations that they all belong to a “parallel structure”, namely the Gülen Movement.

The largest union of judges and prosecutors, YARSAV, whose inclination is left and secular, has been shut down indefinitely. The country’s largest charity group, Kimse Yok Mu, which has a vast network of hospitals and orphanages across Africa and Asia, has also been closed.

All this official data speaks for itself, exposing the magnitude of the “counter wave”.

It raises huge questions for any decent journalist. We would be led to believe that Turkey’s arrested generals – a third of the country’s 347 – are Gülenists. But this doesn’t look at all convincing among political circles in the US capital, according to Hürriyet’s Washington correspondent Tolga Tanış.

What’s perhaps more worrisome is that given the coup attempt, the arrests and the incredible implosion, Turkey’s defence system is in huge crisis, leaving the country very vulnerable to hostile activity, in particular by IS units.

Then, of course, there is the widespread confusion over key institutions such as schools and hospitals being shut down. There is no clarity about the fate of the students and patients.

The emergency rule has sent chills deep into the intellectual and traditionally dissenting elite of Turkey. So far, there has been absolutely no assurance from Erdogan or prime minister Binali Yıldırım that the freedom and rights of those in the media, academia, civil society organisations and political opposition groups will be respected.

On the contrary, an arrest order was issued for 19 local journalists in Ankara. A young reporter with ETHA news agency, Ezgi Özer, was arrested in Dersim province. The rector of Dicle University in Diyarbakır, Ayşegül Jale Saraç was detained as well.

Not so surprisingly, then, there is a widespread mistrust and fear spreading now into the intellectual community in Turkey about what they see as an indiscriminate crackdown.

As my colleague Can Dündar put it in the Guardian on Friday: “‘Fine, we are rid of a military coup, but who is to shelter us from a police state? Fine, we sent the military back to their barracks, but how are we to save a politics lodged in the mosques?”

“And the question goes to a Europe preoccupied with its own troubles: will you turn a blind eye yet again and co-operate because ‘Erdogan holds the keys to the refugees’? Or will you be ashamed of the outcome of your support, and stand with modern Turkey?” Dündar added.

I agree with him and let me add a key point: if this oppressive trend continues with full force members of the media, academia, and civil society, as well as the young and secular who feel victimised and desperate due to the vicious cultural struggle that has been going on for years, will have no choice but emigrate. Europe and the West should brace themselves for this scenario.

Turkey is cracking under its incurable divisions.

A version of this article was originally posted to Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is published here with permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

25 Jul 16 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile

Bahraini human rights defender Nabeel Rajab (Photo: The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy)

This is the tweet that Index on Censorship shared on 14 March 2015 when Nabeel Rajab, the Bahraini human rights campaigner, was challenging a six-month suspended sentence for “denigrating government institutions” for comments about the role of prisons as incubators of extremism. It is also one of the tweets now being used in evidence against Nabeel in a new case the government has brought against him. The latest case charges Nabeel, president of the award-winning Bahrain Center for Human Rights, with “publishing and broadcasting false news that undermines the prestige of the state”.

Nabeel’s attempts to assert his right and the rights of others to free expression are being systematically – and brutally – thwarted by a government that acts with the continued support of allies such as the UK. The King of Bahrain sat next to Queen Elizabeth at her 90th birthday party in March: how much clearer indication could the UK possibly give of its support for a country that continues to torture citizens who disagree with the regime? A country that this weekend ordered the 15-day detention of a poet, and which last year stripped 72 people of their citizenship – including journalists and bloggers – for simply voicing their criticism of the current regime. A country that uses a retweet of solidarity from a UK-based organisation as evidence that Nabeel broadcasts “false news and articles”.

It is not false to suggest Nabeel – and many others – are subjected to continued judicial harassment. Nabeel spent two years in jail between 2012 and 2014 on spurious charges including writing offensive tweets and taking part in illegal protests. He left the country shortly afterwards to raise international awareness of the country’s plight and days after his return was again arrested. Though charged and later pardoned, he remained subject to a travel ban and now faces jail once more.

I met Nabeel during his visit to the UK in August 2014. I had been in my job for just two months and was keen to know how organisations like ours could support individuals like Nabeel, who was awarded the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award in 2012. The meeting remains one of the defining moments of my time at Index: one that has helped to guide my thinking over the past 24 months. “Be there,” was Nabeel’s message. Be there not just when high-profile cases flare up and the eye of the media flickers over a country. Be there when a person fades from the world’s gaze. Be there to remind others that the person still matters.

Nabeel’s comments informed our decision last year to redevelop our Freedom of Expression Awards as a fellowship – offering more sustained support to winners and reaffirming our commitment to be there for the long haul. In recognition of this influence, Nabeel was one of our judges for this year’s awards. Because of the travel ban, imposed after last year’s conviction, he could not join us in person, but he was very much present.

Nabeel is due to stand trial on 5 September — after yet another delay announced on 2 August — over his twitter comments (and, by extension, ours). The kind of comments made every day in the United Kingdom, United States, France, Germany and elsewhere to hold governments to account or simply to vent anger: tweets about conditions in jail, about judicial processes, about the state of the country. In these countries, such comments are – and should be – considered part of the democratic process. In Bahrain, a country that the UK government repeatedly insists is on the “right path” to democracy, such comments land you in jail, solitary confinement, threatened with violence.

And when Bahrain starts using the support of international organisations like ours as evidence with which to condemn human rights activists, it is incumbent on governments like the UK to speak publicly. These governments need to be there, not just for the regimes they support, but in defence of the human rights they themselves claim to uphold and also for the people whose rights are being denied.

25 Jul 16 | Africa, Asia and Pacific, Burkina Faso, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Pakistan, Syria, Yemen

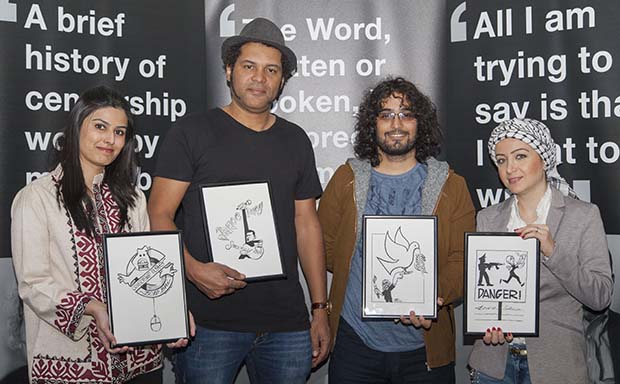

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship

In the short three months since the Index on Censorship Awards, the 2016 fellows have been busy doing important work in their respective fields to further their cause and for stronger freedom of expression around the world.

GreatFire / Digital activism

GreatFire, the anonymous group of individuals who work towards circumventing China’s Great Firewall, has just launched a groundbreaking new site to test virtual private networks within the country.

“Stable circumvention is a difficult thing to find in China so this new site a way for people to see what’s working and what’s not working,” said co-founder Charlie Smith.

But why are VPNs needed in China in the first place? “The list is very long: the firewall harms innovation while scholars in China have criticised the government for their internet controls, saying it’s harming their scholarly work, which is absolutely true,” said Smith. “Foreign companies are also complaining that internet censorship is hurting their day-to-day business, which means less investment in China, which means less jobs for Chinese people.”

Even recent Chinese history is skewed by the firewall. The anniversary of Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 last month went mostly unnoticed. “There was nothing to be seen about it on the internet in China,” Smith said. “This is a major event in Chinese history that’s basically been erased.”

Going forward, Smith is optimistic for growth within GreatFire, and has hopes the new VPN service will reach 100 million Chinese people. “However, we always feel that foreign businesses and governments could do more,” he said. “We don’t see this as a long game or diplomacy; we want change now and so I feel positive about what we are doing but we have less optimism when it comes to efforts outside of our organisation.”

Winning the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Digital Activism has certainly helped morale. “With the way we operate in anonymity, sometimes we feel a little lonely, so it’s nice to know that there are people out there paying attention,” Smith said.

Murad Subay / Arts

During his time in London for the Index awards, Yemeni artist Murad Subay painted a mural in Hoxton, which was the first time he had worked outside of his home country. “It was a great opportunity to tell people what’s going on in Yemen, because the world isn’t paying attention,” he explained to Index.

Since going home, Subay has continued to work with Ruins, his campaign with other artists to paint the walls of Yemen. “We launched in 2011, and have continued to paint ever since.”

Last month, artists from Ruins, including Subay, painted a number of murals in front of the Central Bank of Yemen to represent the country’s economic collapse.

In his acceptance speech at the Index Awards, Subay dedicated his award to the “unknown” people of Yemen, “who struggle to survive”. There has been little change in the situation since in the subsequent months as Yemenis continue to suffer war, oppression, destruction, thirst and — with increasing food prices — hunger.

“The war will continue for a long time and I believe it may even be a decade for the turmoil in Yemen to subside,” Subay says. “Yemen has always been poor, but the situation has gotten significantly worse in the last few years.”

Subay considers himself to be one of the lucky ones as he has access to water and electricity. “But there are many millions of people without these things and they need humanitarian assistance,” he says. “They are sick of what is going on in Yemen, but I do have hope — you have to have hope here.”

The Index award has also helped Subay maintain this hope. As has the inclusion of his work in university courses around the world, from John Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA, and King Juan Carlos University in Madrid, Spain.

Subay’s wife has this month travelled to America to study at Stanford University. He hopes to join her and study fine art. “Since 2001 I have not had any education, and this is not enough,” he explains. “I have ideas in my head that I can’t put into practice because i don’t have the knowledge but a course would help with this.”

Zaina Erhaim / Journalism

Syrian journalist and documentary filmmaker Zaina Erhaim has been based in Turkey since leaving London after the Index Awards in April as travelling back to Syria isn’t currently possible. “We don’t have permission to cross back and forth from the Turkish authorities,” she told Index. “The border is completely closed.”

Erhaim is with her daughter in Turkey, while her husband Mahmoud remains in Aleppo.

“The situation in Aleppo is very bad,” she said. “A recent Channel 4 report by a friend of mine shows that the bombing has intensified, and the number of killings is in the tens per day, which hasn’t been the case for some weeks; it’s terrible.”

The main hospital in Aleppo was bombed twice in June. “Sadly this is becoming such a common thing that we don’t talk about it anymore,” Erhaim added.

She has largely given up on following coverage of the war in Syria through US or UK-based media outlets. “It is such a wasted effort and it’s so disappointing,” she explained. “I follow a couple of journalists based in the region who are actually trying to report human-side stories, but since I was in London for the awards, I haven’t followed the mainstream western media.”

Erhaim has put her own documentary making on hold for now while she launches a new project with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting this month to teach activists filmmaking skills. “We are going to be helping five citizen journalists to do their own short films, which we will then help them publicise,” she said.

Documentary filmmaking is something she would like to return to in future, “but at the moment it is not feasible with the situation in Syria and the projects we are now working on”.

Bolo Bhi / Campaigning

The last time Index spoke to Farieha Aziz, director of Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit, all-female NGO fighting for internet access, digital security and privacy, the country’s lower legislative chamber had just passed the cyber crimes bill.

The danger of the bill is that it would permit the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority to manage, remove or block content on the internet. “It’s part of a regressive trend we are seeing the world over: there is shrinking space for openness, a lot of privacy intrusion and limits to free speech,” Aziz told Index.

Thankfully, when the bill went to the Pakistani senate — which is the upper house — it was rejected as it stood. “Before this, we had approached senators to again get an affirmation as they’d given earlier saying that they were not going to pass it in its current form,” Aziz added.

Bolo Bhi’s advice to Pakistani politicians largely pointed back to analysis the group had published online, which went through various sections of the bill and highlighting what was problematic and what needed to be done.

This further encouraged those senators who were against the bill to get the word out to their parties to attend the session to ensure it didn’t pass. “It’s a good thing to see they’ve felt a sense of urgency, which we’ve desperately needed,” Aziz said.

“The strength of the campaign throughout has actually been that we’ve been able to band together, whether as civil society organisations, human rights organisations, industry organisations, but also those in the legislature,” Aziz added. “We’ve been together at different forums, we’ve been constantly engaging, sharing ideas and essentially that’s how we want policy making in general, not just on one bill, to take place.”

The campaign to defeat the bill goes on. A recent public petition (18 July) set up by Bolo Bhi to the senate’s Standing Committee on IT and Telecom requested the body to “hold more consultations until all sections of the bill have been thoroughly discussed and reviewed, and also hold a public hearing where technical and legal experts, as well as other concerned citizens, can present their point of view, so that the final version of the bill is one that is effective in curbing crime and also protects existing rights as guaranteed under the Constitution of Pakistan”.

A vote on an amended version of the bill is due to take place this week in the senate.

Smockey / Music in Exile Fellow

Burkinabe rapper and activist Smockey became the inaugural Music in Exile Fellow at the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards, and last month his campaigning group Le Balai Citoyen (The Citizen’s Broom) won an Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award.

“This was was given to us for our efforts in the promotion of human rights and democracy in our country,” said Smockey. The award was also given to Y en a marre (Senegal) and Et Lucha (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

“We are trying to create a kind of synergy between all social-movements in Africa because we are living in the same continent and so anything that affects the others will affect us also,” Smockey added.

Le Balai Citoyen has recently been working on programmes for young people and women. “We will also meet the new mayor of the capital to understand all the problems of urbanism,” Smockey added.

While his activism has been getting international recognition, he remains focused on making music with upcoming concerts in Belgium, Switzerland and Germany, and he is currently writing the music for an upcoming album. A major setback has seen Smockey’s acclaimed Studio Abazon destroyed by a fire early in the morning of 19 July. According to press reports the studio is a complete loss. The cause is under investigation.

Despite this, Smockey is still planning to organise a new music festival in Burkina Faso. “We want to create a festival of free expression in arts,” Smockey said. “And we are confident that it will change a lot of things here.”

He is thankful for the exposure the Index Awards have given him over the last number of months. “It was a great honour to receive this award, especially because it came from an English country,” he said. “My people are proud of this award.”

23 Jul 16 | Academic Freedom, Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

It was at the early hours of Friday that a journalist sent a note to her colleagues.

It was at the early hours of Friday that a journalist sent a note to her colleagues.

“We are told by the management that our publication is discontinued with immediate effect,” she said. “We are told to pack our belongings and leave the office. You can’t imagine how sad I am.”

The weekly news magazine Nokta, which had been launched in the aftermath of a military coup in 1980s, is no more.

Lately, under a new management, Nokta belonged to the critical mass of what remained of independent journalism in Turkey, with long reads and popular, bright commentators such as Perihan Mağden and Gükhan Özgün.

My colleague went on to say that the management internal communique cited the loss of a printing house as the reason for the closure. Given the waves of restriction over basic freedoms in the wake of Emergency Rule declared in 81 provinces of Turkey, this explanation came as no surprise.

Commenting on the closure, a Kurdish colleague who has extensively covered the operations in Cizre and Diyarbakır, added: “It’s a disaster to have the media outlets shut down, but it’s even worse to see media professionals left without a job.”

In another incident, Paolo Brera, a well-known reporter with La Repubblica, was held by the police officers at Sultanahmet Square yesterday while interviewing tourists, and taken to police headquarters. At first his whereabouts were unknown, and Italy had to intervene at the highest level to have him released after four hours.

As of Friday afternoon the situation of the columnist and human rights lawyer Orhan Kemal Cengiz was unclear. Cengiz is an international figure and close friend of the Kurdish lawyer Tahir Elçi who was assassinated in Diyarbakır last summer. Among other assignments, Cengiz followed the case of Christian missionaries slain in Malatya in 2007. He attended the UN’s Human Rights Summit in Geneva some months ago, commemorating by explaining the situation to a larger audience. His colleagues are on standby, knowing that he is held at the Anti-Terror Unit in Istanbul. His wife, also a lawyer, had been told that the detention was related to a case from 2014, but nobody has any further details.

The Emergency Rule means that no lawyers other than those appointed by the bar associations are now allowed to have access to all the cases. What is also known is that those who are arrested are held in cells at police headquarters.

Justice Minister Bekir Bozdağ said in an interview yesterday that in “crimes related to terrorist activities” individuals can be detained for at least seven-to-eight days. “Our staff is working on the possibilities of even extending that time,” he said, adding that he shares the concern that it will be very difficult to distinguish innocents from criminals.

The overall situation continues to be opaque, with scarce information, and experienced journalists caution each other to compare what’s being officially stated with what’s really being done. The measures so far leave little doubt that the media and the academia are under severe pressure, and the growing concern is there is an escalation of a clampdown, without much explanation of what the media and academic freedom had to do with the very coup attempt itself.

A version of this article was originally posted to Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is published here with permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

It was at the early hours of Friday that a journalist sent a note to her colleagues.

It was at the early hours of Friday that a journalist sent a note to her colleagues.