13 Jan 16 | Magazine, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

Kunle Olulode, director of Voice for Change England

The opportunity to re-introduce Astrid Lindgren’s children’s literary figure Pippi Longstocking to a new Swedish generation in 2014 should have been a fairly innocuous affair. However, the decision to edit out parts of the programme, which originally aired in 1969, on anti-racist grounds caused a major furore. Two scenes in particular, Pippi’s reference to her father as King of the Negroes and secondly her slit-eyed impersonation of someone from China, were removed, provoking national and international debates about the rights and wrongs of the re-edit.

Critics rounded on the Swedish broadcaster SVT, accusing it of imposing adult PC values on a beloved fictional figure. But this situation is not unique to Sweden. The people who run television programming throughout western Europe are acting in the same way. The programme could be seen as simply part of work reflecting attitudes of a particular period. I fear there is a danger we lose the contextual understanding of the work and an understanding of the period by editing it in this way.

Mark Twain’s classic novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been at the centre of a similar debate in the United States, but the book was always intended to be controversial. Critics rounded on it when it was first published in 1885. The Committee of the Concord Public Library in Massachusetts, publicly declared the book “couched in the language of a rough, ignorant dialect” and that “all through its pages there is a systematic use of bad grammar and an employment of inelegant expressions”.

The enterprising publisher saw this as a “rattling tip-top puff” and used the library ban and …

You can read the full article in the latest Index on Censorship magazine. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

12 Jan 16 | Americas, Cuba, mobile, News and features

August 2015: opening of the Cuban Film Posters exhibition Soy Cuba as part of World Cinema Amsterdam. Credit: Shutterstock / Cloud Mine Amsterdam

“[T]he fault of many of our intellectuals and artists is to be found in their ‘original sin’: they are not authentically revolutionary.”

— Che Guevara, Man and Socialism in Cuba, 1965

Last year was a good one for Cuban artists. With renewed diplomatic relations with the US, a boom in Latin American art and Cuba’s exceptional artistic talent — fostered through institutions such as the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana — works by prominent Cuban artists fetched top dollar at international auctions, and the Cuban film industry was firmly in the international spotlight.

While the end of the embargo brought with it hope for political liberalisation on the island, as with previous periods of promise in Cuban history cases of repression and censorship of dissident artists were rife in 2015.

So let’s begin again: Last year was a good one for Cuban artists who adhere to the country’s long-established revolutionary narrative and don’t embarrass the regime.

The fear of censorship for art that is critical of the government has been fostered through decades of laws and repression that limit freedom of expression. This can mean stigmatisation, the loss of employment and even imprisonment. Charges such as “social dangerousness” and insulting national symbols are so vague they make convictions very easy.

“Artists are among the most privileged people in Cuban society — they make money in hard currency, travel, have frequent interaction with foreigners and they don’t have boring jobs,” explains Coco Fusco, a Cuban-American artist, 2016 Index Freedom of Expression Awards nominee and author of Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba. “Artists function as a window display in Cuba; proof of the success of the system.”

But if an artist engages in political confrontations, they can draw unwanted attention, says Fusco.

One artist accused of doing just that is critically-acclaimed Cuban director and fellow nominee for this year’s Index Awards Juan Carlos Cremata. In 2015, he staged a production of Eugene Ionesco’s Exit the King, about an ageing ruler who refuses to give up power. The play lasted two performances before being shut down by the National Council of Theatre Arts and the Centre for Theatre in Havana.

“Exit the King was banned because according to the minister of culture and the secret police we were mocking Fidel Castro,” Cremata told Index on Censorship. “This wasn’t really true; what they fear is real revolutionary speech in theatre.”

When he spoke out against the move, Cuban authorities terminated his theatre contract, effectively dissolving his company, El Ingenio.

Cremata, whose career spans three decades, confesses the shutting down of Exit the King took him by surprise. “We are living in the 21st century, and according to the official propaganda, Cuba is changing and people can talk about anything,” he says. “This, as it turns out, is a big lie by people who are still dreaming of the revolution.”

“With their censorship, they show how stupid, retrograde and archaic their politics are,” he says.

As so much funding for artists comes from the state, non-conformist artists often find themselves in difficult financial situations. “I’ve had to reinvent my life,” Cremata says. “I’m trying to receive some help from friends who offer to work with me for free, but this will not be eternal, as they have families.”

Cremata himself has an adopted daughter and has her future to think about. “I truly believe life will change and better times will come with or without their approval, but it is very, very hard.”

Art has always been at the centre of Cuban culture, but under Fidel Castro it became a tool for spreading socialist ideas and censorship a tool for tackling dissent. Evidently, Cuba isn’t entirely post-Fidel, explains Fusco. “Fidel is still alive, his brother is in charge and his dynasty is firmly ensconced in the power, with sons, nieces and nephews in key positions,” she says. “Although I don’t think anyone over the age of 10 in Cuba believes the rhetoric anymore.”

Very few may believe the rhetoric, but going against it can still land you in prison, as was the case with Index Awards nominee Danilo Maldonado, the graffiti artist also known as El Sexto. Maldonado organised a performance called Animal Farm for Christmas 2014, where he intended to release two pigs with the names of Raúl and Fidel Castro painted on them. He was arrested on his way to carry out the performance and spent 10 months in prison without trial.

International human rights organisations condemned his imprisonment — during which he was on a month-long hunger strike — as an attack on freedom of expression.

The prospect for improving political freedoms doesn’t look good, and anyone who expected any different due to Cuba’s normalisation of relations with the US is naive, says Fusco.

“Washington is not promoting policy changes to improve human rights,” she says. “Washington is promoting policy changes to 1. develop better ways to exert political influence in Cuba; 2. to revise immigration policies and control the steep increase in Cuban illegal migration to the US; 3. to give US businesses and investment opportunity that they need (particularly agribusiness); 4. to avoid a tumultuous transition at the end of Raul Castro’s term in power that would produce more regional instability (i.e. the US does not want another Iraq, Libya or Syria).”

Even within Cuba there is an absence of discussion about civil liberties, strong voices of criticism of state controls and collective artist-based efforts to promote liberalisation.

“Artists are generally afraid to mingle with dissidents,” says Fusco. “There are a few bloggers who post stories about confrontations with police and political prisoners, a few older human rights activists who collect information about detentions and prison conditions, a handful of opposition groups who advocate for political reforms, but they have virtually no influence on the government.”

In the past, Cuban authorities used the US embargo as an excuse to justify restrictions on freedom of expression. Now that the excuses are running out, it is time for the Cuban government allow its dissidents the same freedoms as its conformists.

Ryan McChrystal is the assistant editor, online at Index on Censorship

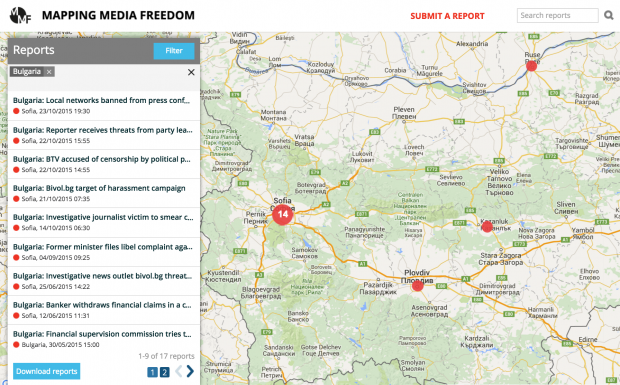

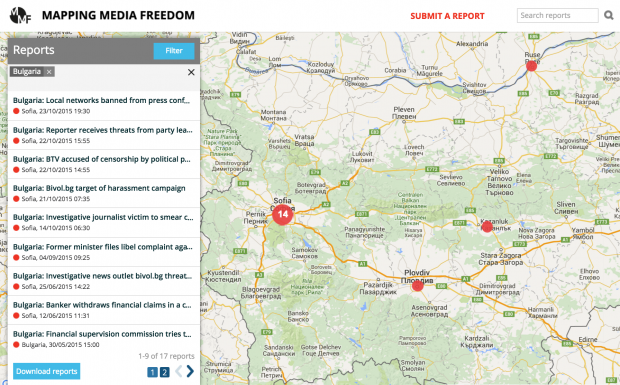

11 Jan 16 | Bulgaria, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Journalists of the Bulgarian investigative news website Bivol.bg are facing an orchestrated smear campaign that’s unusual even for Bulgaria, the worst-ranking EU member in the 2015 Reporters Without Borders press freedom index.

The attacks can be linked to mainstream media outlets controlled by the Bulgarian media mogul and lawmaker Delyan Peevski, and seem to be a response to a number of investigations published recently by Bivol.bg, all involving Peevski in one way or another.

“Even if it is not like in the beginning, the smear campaign did not end,” Bivol’s editor-in-chief, Atanas Chobanov, told Index on Censorship in December 2015.

During the autumn, articles denigrating Chobanov and Assen Yordanov — Bivol’s founder, co-owner and director — began appearing in media outlets such as the Bulgarian weekly Politika, the Telegraph, Monitor and Trud dailies, as well as the news website Blitz, which are controlled either directly or through proxies by Delyan Peevski, an MP from the parliamentary group of the Turkish minority party, Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF).

According to a summary published by OCCRP, the articles allege that Yordanov uses Bivol.bg to publish fake stories to blackmail politicians and business people. The attack pieces allege that Bivol.bg publishes stories about environmental issues to serving the interests of fake eco-activists who pose as people concerned about the environment to extract cash from firms that want to build in the Bulgarian mountains and on the Black Sea coast.

There are allegations saying that Atanas Chobanov is a former Komsomol activist (the youth division of the Bulgarian Communist Party), aspired to a political career, and has links to a businessman whose media strongly oppose Peevski. Some articles insinuate that Chobanov works for foreign intelligence services; and that he lives a luxurious life in Paris where he milks the social welfare system. (The latter allegation is interesting because in 2013, it was Chobanov who uncovered that former planning and investment minister Ivan Danov was collecting €1,800 per month in unemployment benefits in France while working two jobs in Bulgaria.)

The pieces give a thoroughly negative depiction of Chobanov, saying that he is greedy, aggressive, mentally unstable, narcissistic, disliked and unwanted.

The campaign culminated on 10 October, when a crew of the Bulgarian TV Channel 3, a television where Peevski is a co-owner, showed up at the rented apartment in Paris where Chobanov and his family lives.

“I was at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Lillehammer, Norway,” Chobanov said, adding that the crew did not try to contact him by phone, e-mail or by any other means in advance. The journalist believes they must have known that he was away because he made a public announcement about his upcoming trip and he was tweeting from Lillehammer.

Although Bivol.bg was the target of similar articles in the past, the ongoing campaign started when the investigative news site published proof that Peevski is a shareholder at the Bulgarian cigarette maker Bulgartabac, a former state-owned company that underwent a controversial privatization process in 2011.

Then the journalists started publishing a story about the disappearance of €26 million ($28.3 million) from an EU food aid program for the poor, where the majority shareholders of Bulgaria’s First Investment Bank (FIB) were implicated. “After the Bulgarian bank crash, Peevski moved his assets, his credits and deposits to this bank, so this investigation also hurts Peevski’s interests,” Chobanov said.

Next, Bivol.bg broke “Yaneva Gate”, a series of stories based on leaked phone conversations between former Sofia City Court president Vladimira Yaneva and fellow judge Roumyana Chenalova over unlawful surveillance warrants that Yaneva had signed.

In those conversations, the judges mentioned Peevski by his first name, Delyan. “The Prosecutor General, one of the men of Peevski, is also involved,” Chobanov pointed out, adding that the story provoked an earthquake in Bulgarian politics, causing justice minister Hristo Ivanov to resign.

“It is a judicial battle now. We are turning to courts to stop the smear campaign, and we are also defending ourselves from legal complaints filed for the investigations we did in the past,” Chobanov said.

Reporters Without Borders expressed support and sympathy for Chobanov, condemning the smear campaign directed against him. “We can only condemn what are clearly attempts to intimidate Bivol’s journalists,” said Alexandra Geneste, the head of the Reporters Without Borders EU/Balkans desk. “Their investigative work is perfectly legitimate and we express our most sincere support and sympathy for them.”

The smear campaign orchestrated by the media outlets controlled by Peevski took an unexpected turn when they accused Xavier Lapeyre de Cabanes, the French Ambassador to Bulgaria with unacceptable meddling in Bulgaria’s affairs after he shared on Twitter a link to the press release by Reporters Without Borders with the comment: “Press freedom has no borders.”

The Bulgarian Association Network for Free Speech also issued a position saying that “the integrity of Bivol’s investigations and publications has not been and is not challenged in any way, despite repeated attempts to pressure our colleagues. (…) We have no reason to doubt the good faith of our colleagues, the journalist from Bivol (…).”

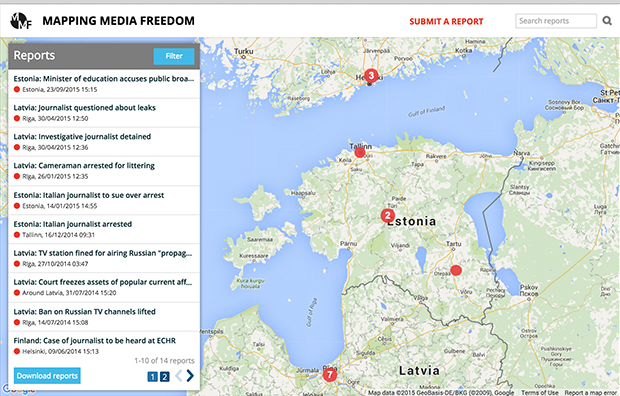

08 Jan 16 | Belarus, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Turkey

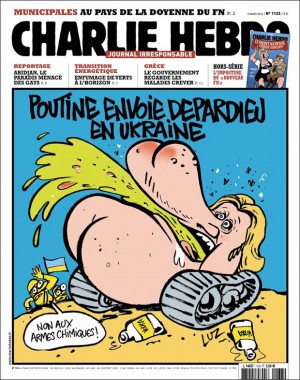

The attacks on the offices of satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris in January set the tone for conditions for media professionals in 2015. Throughout the year, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom correspondents verified a total of 745 violations of media freedom across Europe.

From the murders of journalists in Russia, Poland and Turkey to the growing threat posed by far-right extremists in Germany and government interference in Hungary — right down to the increasingly harsh legal measures imposed on reporters right across the continent — Mapping Media Freedom exposed many difficulties media workers face in simply doing their jobs.

“Last year was a tumultuous one for press freedom; from the attacks at Charlie Hebdo to the refugee crisis-related aggressions, Index observed many threats to the media across Europe,” said Hannah Machlin, Index on Censorship’s project officer for the Mapping Media Freedom project. “To highlight the important cases and trends of the year, we’ve asked our correspondents, who have been carefully monitoring the region, to discuss one violation each that stood out to them.”

Belarus / 19 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

Journalist blocked from shooting entrance to polling station

“It demonstrates the Belarusian authorities’ attitude to media as well as ‘transparency’ of the presidential election – the most important event in the current year.” — Ольга К.-Сехович

Greece / 15 verified reports in 2015

Four journalists detained and blocked from covering refugee operation

“This is important because it is typical ‘attempt to limit press freedom’, as the Union wrote in a statement and it is not very hopeful for the future. The way refugees and migrants are treated is very sensitive and media should not be prevented from covering this issue.” — Christina Vasilaki

Hungary / 57 verified reports in 2015

Serbian camera crew beaten by border police

“These physical attacks, the harsh treatment and detention of journalists are striking because the Hungarian government usually uses ‘soft censorship’ to control media and journalists, they rarely use brute force.” — Zoltan Sipos

Italy / 72 verified reports in 2015

Italian journalists face up to eight years in prison for corruption investigation

“I chose it because this case is really serious: the journalists Emiliano Fittipaldi and Gianluigi Nuzzi are facing up to eight years in prison for publishing books on corruption in the Vatican. This case could have a chilling effect on press freedom. It is really important that journalists investigate and they must be free to do that.” — Rossella Ricchiuti

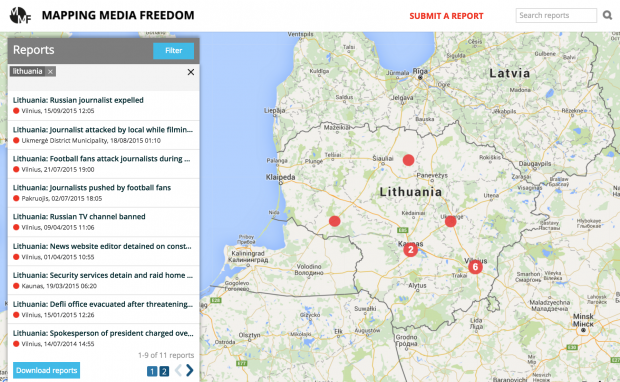

Lithuania / 9 verified reports in 2015

Journalist repeatedly harassed and pushed out of local area

“I chose it because I found it relevant to my personal experience and the fellow journalist has been the only one to have responded to my hundreds of e-mails — including requests to fellow Lithuanian journalists to share their personal experience on media freedom.” — Linas Jegelevicius

Macedonia / 27 verified reports in 2015

Journalist publicly assaults another journalist

“I have chosen this incident because it best describes the recent trend not only in Macedonia and my other three designated countries, Croatia, Bosnia and Montenegro, but also in the whole region. And that is polarization among journalists, more and more verbal and, like in this unique case, physical assaults among colleagues. It best describes the ongoing trend where journalists are not united in safeguarding public interest but are nothing more than a tool in the hands of political and financial elites. It describes the division between pro-opposition and pro-government journalists. It is a clear example of absolute deviation from the journalistic ethic.” — Ilcho Cvetanoski

Poland / 11 verified reports in 2015

Law on public service broadcasting removes independence guarantees

“The new media law, which was passed through Poland`s two-chamber parliament in the last week of December, constitutes a severe threat to pluralism of opinions in Poland, as it is aimed at streamlining public media along the lines of the PiS party that holds the overall majority. The law is currently only awaiting president Duda’s signature, who is a close PiS ally.” — Martha Otwinowski

Portugal / 9 verified reports in 2015

Two-thirds of newspaper employees will be laid off

“It’s a clear picture of the media in Portugal, which depends on investors who show no interest in a healthy, well-informed democracy, but rather in how owning a newspaper can help them achieve their goals — and when these are not met they don’t hesitate to jump boat, leaving hundreds unemployed.” — João de Almeida Dias

Russia / 37 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

Media freedom NGO recognised as foreign agent, faces closure

“The most important trend of the 2015 in Russia is the continuing pressure over the civil society. More than 100 Russian civil rights advocacy NGOs were recognized as organisations acting as foreign agents which leads to double control and reporting, to intimidation and insulting of activists, e.g., by the state-owned media. Many of them faced large fines and were forced to closure.” — Andrey Kalikh

Russia / 37 verified reports between May-Dec 2015

TV2 loses counter claim to renew broadcasting license Roskomnadzor

“It illustrates the crackdown on independent local media, which can not fight against the state officials even if they have support from the audience and professional community.” — Ekaterina Buchneva

Serbia / 41 verified reports in 2015

Investigative journalist severely beaten with metal bars

“It’s a disgrace and a flash-back to Serbia’s dark past that a journalist, who’s well known for investigating high-level corruption, get’s beaten up with metal bars late at night by ‘unknown men’.” — Mitra Nazar

Turkey / 97 verified reports in 2015

Police storm offices of Koza İpek, interrupting broadcast

“The raid on Bugün and Kanaltürk’s offices just days ahead of parliamentary elections was a drastic example — broadcasts were cut by police and around 100 journalists ended up losing their jobs over the next month — of how the current Turkish government tries to strong-arm media organisations.” — Catherine Stupp

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

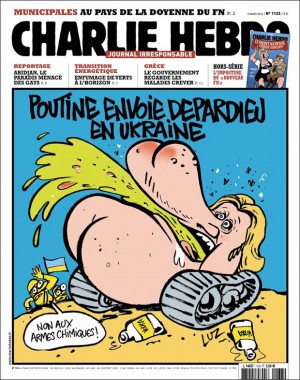

07 Jan 16 | Campaigns, Europe and Central Asia, France, mobile, Statements

On the anniversary of the brutal attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to the defence of the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that some may consider offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack, which left 11 dead and 12 wounded, was a horrific reminder of the violence to which journalists, artists and other critical voices are subjected in a global atmosphere marked by increasing intolerance of dissent. The killings inaugurated a year that has proved especially challenging for proponents of freedom of opinion.

Non-state actors perpetrated violence against their critics largely with impunity, including the brutal murders of four secular bloggers in Bangladesh by Islamist extremists, and the killing of an academic, M M Kalburgi, who wrote critically against Hindu fundamentalism in India.

Despite the turnout of world leaders on the streets of Paris in an unprecedented display of solidarity with free expression following the Charlie Hebdo murders, artists and writers faced intense repression from governments throughout the year. In Malaysia, cartoonist Zunar is facing a possible 43-year prison sentence for alleged ‘sedition’; in Iran, cartoonist Atena Fardaghani is serving a 12-year sentence for a political cartoon; and in Saudi Arabia, Palestinian poet Ashraf Fayadh was sentenced to death for the views he expressed in his poetry.

Perhaps the most far-reaching threats to freedom of expression in 2015 came from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries including France, Britain and Germany issued a statement in which they called on Internet service providers to identify and remove online content ‘that aims to incite hatred and terror.’ In July, the French Senate passed a controversial law giving sweeping new powers to the intelligence agencies to spy on citizens, which the UN Human Rights Committee categorised as “excessively broad”.

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the State. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On the anniversary of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, we, the undersigned, call on all Governments to:

- Uphold their international obligations to protect the rights of freedom of expression and information for all, and especially for journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders to publish, write and speak freely;

- Promote a safe and enabling environment for those who exercise their right to freedom of expression, and ensure that journalists, artists and human rights defenders may perform their work without interference;

- Combat impunity for threats and violations aimed at journalists and others exercising their right to freedom of expression, and ensure impartial, timely and thorough investigations that bring the executors and masterminds behind such crimes to justice. Also ensure victims and their families have expedient access to appropriate remedies;

- Repeal legislation which restricts the right to legitimate freedom of expression, especially vague and overbroad national security, sedition, obscenity, blasphemy and criminal defamation laws, and other legislation used to imprison, harass and silence critical voices, including on social media and online;

- Ensure that respect for human rights is at the heart of communication surveillance policy. Laws and legal standards governing communication surveillance must therefore be updated, strengthened and brought under legislative and judicial control. Any interference can only be justified if it is clearly defined by law, pursues a legitimate aim and is strictly necessary to the aim pursued.

PEN International

ActiveWatch – Media Monitoring Agency

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian Association of Journalists

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Bytes for All

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Independent Journalism – Romania

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Comité por la Libre Expresión – C-Libre

Committee to Protect Journalists

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Foundation for Press Freedom – FLIP

Freedom Forum

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression – Turkey

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

Instituto de Prensa y Libertad de Expresión – IPLEX

Instituto Prensa y Sociedad de Venezuela

International Federation of Journalists

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Journaliste en danger

Maharat Foundation

MARCH

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Foundation for West Africa

National Union of Somali Journalists

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

Reporters Without Borders

South East European Network for Professionalization of Media

Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters – AMARC

PEN Mali

PEN Kenya

PEN Nigeria

PEN South Africa

PEN Eritrea in Exile

PEN Zambia

PEN Afrikaans

PEN Ethiopia

PEN Lebanon

Palestinian PEN

Turkish PEN

PEN Quebec

PEN Colombia

PEN Peru

PEN Bolivia

PEN San Miguel

PEN USA

English PEN

Icelandic PEN

PEN Norway

Portuguese PEN

PEN Bosnia

PEN Croatia

Danish PEN

PEN Netherlands

German PEN

Finnish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

Slovenian PEN

PEN Suisse Romand

Flanders PEN

PEN Trieste

Russian PEN

PEN Japan

07 Jan 16 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Statements, United Kingdom

When I started working at Index on Censorship, some friends (including some journalists) asked why an organisation defending free expression was needed in the 21st century. “We’ve won the battle,” was a phrase I heard often. “We have free speech.”

There was another group who recognised that there are many places in the world where speech is curbed (North Korea was mentioned a lot), but most refused to accept that any threat existed in modern, liberal democracies.

After the killing of 12 people at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, that argument died away. The threats that Index sees every day – in Bangladesh, in Iran, in Mexico, the threats to poets, playwrights, singers, journalists and artists – had come to Paris. And so, by extension, to all of us.

Those to whom I had struggled to explain the creeping forms of censorship that are increasingly restraining our freedom to express ourselves – a freedom which for me forms the bedrock of all other liberties and which is essential for a tolerant, progressive society – found their voice. Suddenly, everyone was “Charlie”, declaring their support for a value whose worth they had, in the preceding months, seemingly barely understood, and certainly saw no reason to defend.

The heartfelt response to the brutal murders at Charlie Hebdo was strong and felt like it came from a united voice. If one good thing could come out of such killings, I thought, it would be that people would start to take more seriously what it means to believe that everyone should have the right to speak freely. Perhaps more attention would fall on those whose speech is being curbed on a daily basis elsewhere in the world: the murders of atheist bloggers in Bangladesh, the detention of journalists in Azerbaijan, the crackdown on media in Turkey. Perhaps this new-found interest in free expression – and its value – would also help to reignite debate in the UK, France and other democracies about the growing curbs on free speech: the banning of speakers on university campuses, the laws being drafted that are meant to stop terrorism but which can catch anyone with whom the government disagrees, the individuals jailed for making jokes.

And, in a way, this did happen. At least, free expression was “in vogue” for much of 2015. University debating societies wanted to discuss its limits, plays were written about censorship and the arts, funds raised to keep Charlie Hebdo going in defiance against those who would use the “assassin’s veto” to stop them. It was also a tense year. Events discussing hate speech or cartooning for which six months previously we might have struggled to get an audience were now being held to full houses. But they were also marked by the presence of police, security guards and patrol cars. I attended one seminar at which a participant was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards. Newspapers and magazines across London conducted security reviews.

But after the dust settled, after the initial rush of apparent solidarity, it became clear that very few people were actually for free speech in the way we understand it at Index. The “buts” crept quickly in – no one would condone violence to deal with troublesome speech, but many were ready to defend a raft of curbs on speech deemed to be offensive, or found they could only defend certain kinds of speech. The PEN American Center, which defends the freedom to write and read, discovered this in May when it awarded Charlie Hebdo a courage award and a number of novelists withdrew from the gala ceremony. Many said they felt uncomfortable giving an award to a publication that drew crude caricatures and mocked religion.

Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom recorded 745 violations against media freedom across Europe in 2015.

The problem with the reaction of the PEN novelists is that it sends the same message as that used by the violent fundamentalists: that only some kinds of speech are worth defending. But if free speech is to mean anything at all, then we must extend the same privileges to speech we dislike as to that of which we approve. We cannot qualify this freedom with caveats about the quality of the art, or the acceptability of the views. Because once you start down that route, all speech is fair game for censorship – including your own.

As Neil Gaiman, the writer who stepped in to host one of the tables at the ceremony after others pulled out, once said: “…if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

Index believes that speech and expression should be curbed only when it incites violence. Defending this position is not easy. It means you find yourself having to defend the speech rights of religious bigots, racists, misogynists and a whole panoply of people with unpalatable views. But if we don’t do that, why should the rights of those who speak out against such people be defended?

In 2016, if we are to defend free expression we need to do a few things. Firstly, we need to stop banning stuff. Sometimes when I look around at the barrage of calls for various people to be silenced (Donald Trump, Germaine Greer, Maryam Namazie) I feel like I’m in that scene from the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels where a bunch of gangsters keep firing at each other by accident and one finally shouts: “Could everyone stop getting shot?” Instead of demanding that people be prevented from speaking on campus, debate them, argue back, expose the holes in their rhetoric and the flaws in their logic.

Secondly, we need to give people the tools for that fight. If you believe as I do that the free flow of ideas and opinions – as opposed to banning things – is ultimately what builds a more tolerant society, then everyone needs to be able to express themselves. One of the arguments used often in the wake of Charlie Hebdo to potentially excuse, or at least explain, what the gunmen did is that the Muslim community in France lacks a voice in mainstream media. Into this vacuum, poisonous and misrepresentative ideas that perpetuate stereotypes and exacerbate hatreds can flourish. The person with the microphone, the pen or the printing press has power over those without.

It is important not to dismiss these arguments but it is vital that the response is not to censor the speaker, the writer or the publisher. Ideas are not challenged by hiding them away and minds not changed by silence. Efforts that encourage diversity in media coverage, representation and decision-making are a good place to start.

Finally, as the reaction to the killings in Paris in November showed, solidarity makes a difference: we need to stand up to the bullies together. When Index called for republication of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons shortly after the attacks, we wanted to show that publishers and free expression groups were united not by a political philosophy, but by an unwillingness to be cowed by bullies. Fear isolates the brave – and it makes the courageous targets for attack. We saw this clearly in the days after Charlie Hebdo when British newspapers and broadcasters shied away from publishing any of the cartoons featuring the Prophet Mohammed. We need to act together in speaking out against those who would use violence to silence us.

As we see this week, threats against freedom of expression in Europe come in all shapes and sizes. The Polish government’s plans to appoint the heads of public broadcasters has drawn complaints to the Council of Europe from journalism bodies, including Index, who argue that the changes would be “wholly unacceptable in a genuine democracy”.

In the UK, plans are afoot to curb speech in the name of protecting us from terror but which are likely to have far-reaching repercussions for all. Index, along with colleagues at English PEN, the National Secular Society and the Christian Institute will be working to ensure that doesn’t happen. This year, as every year, defending free speech will begin at home.

07 Jan 16 | mobile, News and features, South Africa

Jacob Zuma (Photo: Jordi Matas / Demotix)

With the new year comes a new battle in South Africa as critics hit back at the proposed “draconian” Cybercrimes and Cybersecurity Bill they say doesn’t differentiate “between espionage and an act of journalism”.

The bill comes against the backdrop of ongoing government hostility towards the media. Exposés by journalists of corruption and cronyism within the ranks of the governing African National Congress (ANC) have led to accusations by the party that the media casts it in a “negative light” and acts in opposition to it.

On the face of it, the legislation is a ham-fisted attempt to push through by stealth key aspects of the stalled and deeply flawed Protection of State Information Bill, which was first introduced in parliament in March 2010.

Dubbed the Secrecy Bill, it has reached the penultimate step in the legislative process, requiring only that President Jacob Zuma sign it into law. But, in the face of stiff opposition and threats of a Constitutional Court challenge, it has been gathering dust on the president’s desk for over two years, unsigned.

“Whole sections of the [Cybercrimes] Bill are copy-and-paste from the Secrecy Bill,” says Murray Hunter, a spokesman for the freedom of expression Right2Know (R2K) campaign. A draft version of the bill was published in August last year, with two months allowed for comments.

In a preliminary submission, R2K says some provisions of the Cybercrimes Bill go way beyond those contained in the Secrecy Bill and include “harsh, draconian penalties that would muzzle journalists, whistleblowers and data activists”.

The bill makes it an offence to “unlawfully and intentionally” hold, communicate, deliver, make available or receive data “which is in possession of the state and which is classified”. Penalties range from five to 15 years in jail and, worryingly, there is no public interest defence or whistleblower protection.

R2K has also highlighted some of its key objections to the bill in a document entitled What’s Wrong With the Cybercrimes Bill: The Seven Deadly Sins.

Hunter concedes that while policies that promote the online security of ordinary citizens are necessary, the bill is part of a raft of new “cybercrime laws popping up across the world that threaten internet freedom”.

“The policy debates in the US and UK are examples of a renewed appetite for backdoor access to privately-owned networks,” he says. “The idea is usually that governments say they want to users to have greater security against ‘outside’ threats, but still want government agencies to be able to penetrate that security.”

The bill effectively hands over the keys of the internet to South Africa’s Ministry of State Security and would dramatically increase the state’s power to snoop on users and wrests governance away from civilian bodies.

“Remember that security means protecting people’s information not only from ‘cybercriminals’, but also from state surveillance,” says Hunter.

Put another way, it’s a bit like having a really great lock on your front door, but leaving the spare key under the mat; either a system is secure against all threats or it is vulnerable to all threats.

Another big concern is that the bill, in its current form would potentially criminalise digital security analysts.

“One of the major protections for internet users’ security is a global community of security analysts and researchers who test the systems, apps and websites as a civic duty, in order to point out and fix security flaws that put the general public at risk,” says Hunter. “Basically, they are online activists who are constantly trying to find security weaknesses in other people’s systems [often belonging to governments and private companies] in order to point them out and get them fixed.”

But the bill would make these practices a criminal offence unless it was “authorised”, and in doing so would potentially make ordinary users less safe.

All of these moves contain uncomfortable historical echoes — it’s only been 22 years since South Africa became a democracy, and surveillance against citizens was among the apartheid government’s notorious specialties.

So the idea of a democratically-elected government, backed up by laws that legitimise intercepting its private citizens’ information, is especially fraught.

As temperatures soar and an “epic drought” tightens its grip on the country, all indications are that it’s going to be a long, hot summer in more ways than one, as activists and journalists prepare to fend off yet another attempt to curb South Africa’s hard-won freedom.

06 Jan 16 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Serbia

It was a Wednesday morning in early November when investigative journalist Slobodan Georgijev opened Informer, one of Serbia’s notorious tabloids. He had just arrived at his office, the newsroom of Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), one of Serbia’s few independent media outlets. When he turned the page he was shocked by what he saw; a picture of his own face amongst two others, in an article calling three media outlets known for critical reporting of the Serbian government, including BIRN, “foreign spies”.

“It was funny and unpleasant at the same time,” Georgijev recalled, speaking to Index on Censorship. “Funny because I knew that this is just a campaign by Informer to undermine the credibility of independent journalists.” More importantly, he had begun worry about his own safety. “It’s also unpleasant because you never know how people will interpret such defamations.”

Several independent media houses — including BIRN, as well as Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK) and Center for Investigative Journalism Serbia (CINS) — have alleged that pro-government tabloids like Informer are running a smear campaign against them.

The first major incident followed the publication of a story about the cancellation of Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic’s vacation in August 2015. Informer published an article saying that Vucic was forced to cancel his two day vacation in Serbia due to reporters from BIRN and CINS allegedly booking a room next to his.

The same newspaper also wrote that BIRN and CINS were meeting with European Union representatives on a weekly basis to plan to bring down the government.

“We are basically accused of being financed by the EU to work against our government,” Branko Cecen, director of CINS, told Index on Censorship. Cecen, like Georgiev, was also pictured and called a foreign spy in Informer. “Expressions like ‘foreign mercenaries’ and ‘joint criminal activity against their own state’ have been used.”

Informer newspaper is openly affiliated with the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) of prime minister Aleksandar Vucic and has frequently been accused of political bias in favour of the party and the prime minister.

CINS, KRIK and BIRN have long reported on what they see as a slew of regular negative articles about themselves in tabloid newspapers with close ties to the government. There is no doubt that the three news outlets are targets because of their critical reporting on the government.

One of BIRN’s stories revealed a contract the Serbian government had signed with the national carrier of United Arab Emirates, Etihad Airways, to take over it’s state-owned counterpart Air Serbia. The deal had been financially damaging for Serbia, which was kept from the public until BIRN obtained and published the contract.

Another story investigated alleged corruption concerning a project for pumping out a flooded coal mine. BIRN found out that Serbia’s state-owned power company had awarded a contract to dewater the mine to a company who’s director is a close friend of the prime minister.

The coal mine revelations led to an angry speech about BIRN by Vucic on national television saying: “Tell those liars that they have lied again(.”

He also attacked the EU delegation in Serbia for being involved in discrediting the government by financing BIRN. “They got the money from Davenport and the EU to speak against the Serbian government,” the prime minister said, naming Michael Davenport, the head of the EU delegation in Belgrade.

BIRN’s editor-in-chief Gordana Igric told Index on Censorship she sees a resemblance to Serbia’s difficult nineties. “This reminds me of the regime of Slobodan Milosevic, a time when the prime minister also had a prominent role and critical journalists and NGOs were marked as foreign mercenaries,” she said. “What’s happening in Serbia today makes you feel sad and confused.”

Independent journalists find the path that the prime minister is taking alarming. Some compare him with the Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan or the Russia’s Vladimir Putin. According to Cecen, the level of freedom of expression is at the lowest level since the time of strongman Milosevic. “There is an aggressive campaign against anybody and anything criticising the prime minister and his policies”, he said. “The prime minister has taken over most media in Serbia, especially national TV networks, but also local ones. His small army of social media commentators is terrorising the internet. It is quite bleak and frustrating.”

Regardless of Vucic’s verbal attacks towards the EU delegation, Serbia has opened the first two chapters in its EU membership negotiation in December 2015. This represents a big step towards eventual membership of the European Union. But the latest progress report on Serbia (November 2015) says the country needs to do much more in terms of fighting corruption, the independence of the judiciary and ensuring media freedom.

“The concern over freedom of expression is always expressed in these reports,” Cecen said. “But we see no influence of such reports since situation with media and freedom of expression is deteriorating daily.” Cecen is disappointed in the European Union’s support for independent media in Serbia and finds that EU officials show too much support for the Serbian government and the prime minister.

After he had seen his own face in the paper, Georgiev picked up the phone and called up Informer’s editor-in-chief Dragan Vučićević to ask for a better picture in the next paper. Georgiev jokes about it and clearly doesn’t let accusations and threats hold him back. “People around me are making jokes”, he said. “They call me a foreign mercenary, an enemy of the state.”

Georgiev pressed charges for defamation against Informer. “We are living in a state of constant emergency,” he continued, concerned about the state of press freedom in his country. “Serbia is not like Turkey. But it goes very fast in that direction.”

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

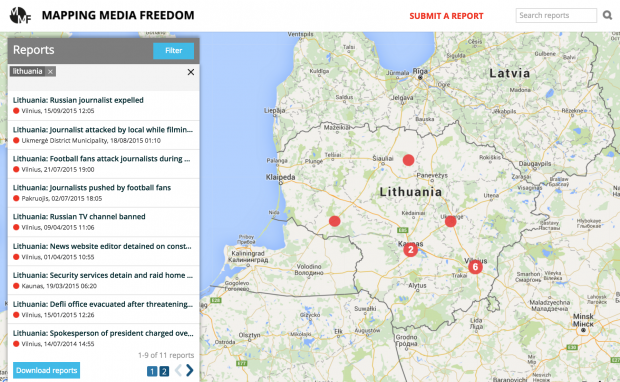

05 Jan 16 | Lithuania, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

RTR Planeta, a Russian language channel broadcasting in Lithuania, has repeatedly run into conflict with the country’s television regulator.

In December, the Lithuanian Radio and Television Commission ordered RTR Planeta to be moved to paid TV packages after it broadcast material that the agency said instigated racial hatred and warfare. The programme in question was the 29 November episode of Sunday Evening with Vladimir Solovyov, which discussed the downing of a Russian plane by the Turkish airforce.

Russian MP Vladimir Zhirinovsky, who was a guest on the programme, said Turkish people were “a nation of wild barbarians,” and said that Turkey should be “brought to its knees” through military attacks.

“We need an air raid on any part of Turkey (…), the Turkish army must be destroyed,” said Zhirinovsky.

This is the second time the programme has prompted the regulator to take action. In April 2015, RTR Planeta was blocked from broadcasting for three months for allegedly “inciting discord and warmongering” over the conflict in Ukraine.

The content in question included a tirade against the Baltic countries by ultra-nationalist Russian politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky on the Sunday Evening With Vladimir Solovjev programme. Zhirinovsky said that Poland and the Baltic states would be “wiped out” should a war break out between Russia and NATO.

Although Lithuanian politicians and media experts agreed on the inflammatory nature of RTR Planeta content, especially the comments made by Zhirinovsky, some media pundits have expressed doubt over the decision to shut the channel down for three months. It resumed broadcasting on 13 July 2015.

In April, Audris Matonis, news service director at Lithuania’s national LRT broadcaster, rejected criticism that the ban was excessive and amounted to censorship. He insisted that “all should realise that what they’re advocating is non-compliance with Lithuanian law”.

But Gintautas Mazeikis, director of the Political Theory Department at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, took issue when speaking to Delfi.lt. “Do we want and seek diplomatic and other means to influence Russian channels, or are we only trying to co-operate with cable TV service providers so they change their packages and broadcast more Polish or Ukrainian TV?” he said. “Do we want to explain and encourage critical thinking among speakers of Ukrainian, Belarusian, Russian and Polish who live in Lithuania?”

Aidas Puklevičius, a journalist and author, insisted that the broadcast ban may not have been the best decision and reasoned that the situation should improve once the generation of people who speak only Russian as a foreign language gives way to one which is more fluent in English.

“Russia will then lose its only vehicle for exporting soft power, something it has very little of,” Puklevičius said to Delfi.it. “Russia did not invent Pepsi Cola, nor jeans, nor Hollywood. Russia’s only strength is its ability to play on Soviet nostalgia.”

Media professionals in Lithuania have increasingly found themselves taking sides in the Ukraine conflict.

“Unfortunately, Russia-Ukraine warfare has become part of journalism in Lithuania and not surprisingly, all the Lithuanian news, except for some reports on the State Lithuanian TV, are concerned with the same issue: how atrocious the Kremlin-backed Russian insurgents are and how courageous the Ukrainians are,” a Lithuanian journalist, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity, told Index on Censorship. “Why is it happening? In any warfare, you’d expect analysis and different points of view, but none of it could be found on Lithuanian TV.”

The journalist said he had stopped watching Lithuanian TV news and has switched to German TV channels which air many different views on the conflict.

In January 2015, Dainius Radzevicius, the chairman of Lithuania’s Union of Journalists, wrote a commentary piece in which he said “polarisation of the media is something we all have to admit is happening, and it has been very palpable for the last couple of years not only in the Lithuanian media but elsewhere too”.

Radzevicius said the problem began as a result of economic conditions, but it is fueled by the geopolitical situation, including the conflict in Ukraine.

“Against this backdrop, we may now have less of a variety of opinions on the radio waves, the TV screens or the newspaper pages; but it is necessary to resist the powerful and obtrusive propaganda coming from the East, therefore, what I call our ‘white propaganda’ is necessary during the times,” he said in the piece.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

04 Jan 16 | Campaigns, Mapping Media Freedom, Poland

Update: President Andrzej Duda of Poland signed the new law into effect on 7 January, 2016.

The undersigned press freedom and media organisations – European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), European Broadcasting Union (EBU), Association of European Journalists (AEJ), Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and Index on Censorship – are outraged by the proposed bill, hastily introduced by the majority party in Poland on 29 December 2015 for immediate adoption, without any consultation, abolishing the existing safeguards for pluralism and independence of public service media governance in Poland.

The introduction of a system whereby a government minister can appoint and dismiss at its own discretion the supervisory and management boards goes against basic principles and established standards of public service media governance throughout Europe. If the Polish Parliament passes these measures, Poland will create a regressive regime which will be without precedent in any other EU country.

We consider that the proposed measures will represent a retrograde step making more political, and thus less independent, the appointment of those in charge of the governance of public service media in Poland.

We urge the Polish authorities to resist any temptation to strengthen political control over the media.

To date, Poland can boast an excellent track record in terms of freedom of the media, which ranks in the top category in the Reporters without Borders World Press Freedom Index 2015 as well as in the 2015 Freedom House report on political rights and civil liberties.

TVP reaches more than 90% of the Polish population every week and had about 30% of the TV broadcasting market in Poland in 2014, which is higher than in the case of most public TV channels in Central and Eastern Europe.

Signatories

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

European Broadcasting Union (EBU)

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Index on Censorship

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

04 Jan 16 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, Netherlands, News and features

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Credit: Shutterstock / Littleaom

Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum is in the process of removing terms visitors may find offensive, including “negro”, “dwarf” and “Indian”, from digitised titles and descriptions of around 220,000 pieces of artwork, replacing them with less racially-charged terminology.

The titles of 8,000 pieces of art on display were updated in time for the museum’s reopening in 2013 after a decade-long renovation, and the museum has now begun work to remove “offensive” language from the museum’s digitised collections.

This includes a 1900 painting by Dutch artist Simon Maris originally called “Young Negro-Girl” which will now be called “Young Girl Holding a Fan”.

The head of the Rijksmuseum Martine Gosselink, who initiated the project said: “The point is not to use names given by whites to others.”

“We Dutch are called kaas kops, or cheeseheads, sometimes, and we wouldn’t like it if we went to a museum in another country and saw descriptions of images of us as ‘kaas kop woman with kaas kop child’,” she added: “And that’s exactly the same as what’s happening here.”

Other words to be removed from the collections include Mohammedan, an old word for Muslim; and Hottentot, a name given to Dutch people by the Khoi people of South Africa, meaning stutterer.

In the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, which tackles taboos and the breaking down of social barriers, Kunle Olulode discusses the problems with editing out racist language from books and films. “Should we not accept that films and TV programmes set in the past will include some stereotypical images of minorities?”, he writes. However uncomfortable these words may seem, they should not be censored as they provide vital insights into history.

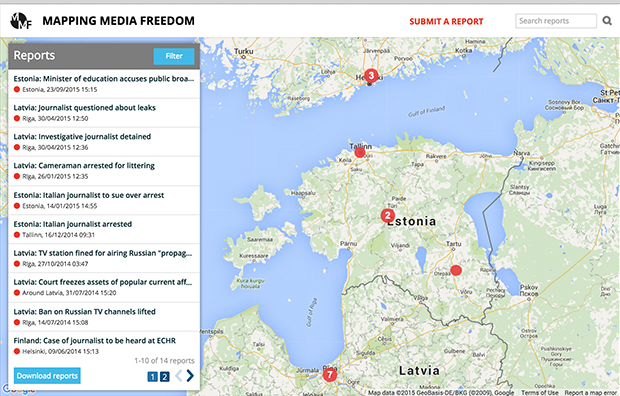

04 Jan 16 | Estonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

In late November 2014, Estonia’s parliament made a historic decision to launch a Russian-language TV-channel as part of ERR, Estonia’s public broadcaster. A year later the channel is a reality: ETV+, ERR’s third channel debuted on 28 September.

The launch passed quite quietly, compared to the reaction that greeted the decision to create the channel. There were discussions about what the opening of a Russian-language channel in Estonia would mean. Would it be a tool of government propaganda or a knitting together of Estonia’s two communities, Estonian and Russian speakers into one community? From Russia there were clear expectations of a counter-weight to Russian media, which is widely followed by Estonia’s Russian speakers.

Speaking at a media conference hosted by ERR in June 2015, the ETV+ chief editor Darja Saar — a Russian project manager with no media experience — described the goals of the new channel: “We gave up the classical media rules from the very beginning, when we decided that we are not going to tell people what is right or wrong. Instead, we will follow people’s wishes – they are tired of just words and want deeds.”

The new TV channel aims not only to be an informer, educator and entertainer in the mould of a classical public service broadcasting channel but a leader in society and a hands-on problem solver.

In its two months on air, though, ETV+ has operated mostly as a traditional TV-channel offering morning programmes, debates, films and news. As required by law, all programmes are subtitled in Estonian. While geared toward Estonia’s Russian speakers, the station’s audience is mostly ethnic Estonians. In its debut week, ETV+ attracted 294,000 viewers. Ethnic Estonians accounted for 217,000 of the total and the other 77,000 were other ethnicities. On an average day during its first week 97,000 watched ETV+. On 28 September, its first day, 120,000 tuned in to sample the new station’s offerings.

ERR board member Ainar Ruussaar pointed out that ETV+ is a long-term project to improve Estonian society and was not about ratings. Yet the failure to draw a larger share of the Russian-speaking audience in the country may put that mission in jeopardy.

ERR has a fraught history with Russian-language programming. Promotion of Estonian language and culture has always been one of its core values. This served it well while it was under the Soviet system. Later, it countered Russian propaganda. But while times changed, ERR did not sufficiently move away from its core. In the early 2000s, the broadcaster, then under budgetary pressures, cut its slate of offerings in Russian. For years after its sole Russian-language production was a little-watched news programme.

In 2007, there was a serious discussion about launching a new Russian-language station after the 27 April violence sparked by the removal of the Bronze Soldier, a World War II memorial in Tallinn’s city centre. Then the political decision in favour of the Russian-language channel in Estonian Television was only one step away and there was readiness in the Russian-speaking audience to watch it. But as the riots faded, funding to get the project off the ground faltered and the opportunity to tie Russian speakers into ERR was missed. The country’s then prime minister Andrus Ansip said it was too difficult to compete with Russian TV channels so ERR’s Russian-language offerings would be limited to radio.

ETV+ is dancing on the razor’s edge. If it covers politics too much it will raise the ire of politicians who could cut its funding. Too much pro-government propaganda could turn off the Russian-speaking audience. Lurking in the background are ratings challenges that could force it to air infotainment and entertainment programmes.

As ETV+ turns two months old, it remains to be seen how it will develop. But connecting with Estonia’s Russian-speaking citizens must be its first goal.

This article was originally posted at indexoncensorship.org

This article was updated on 5/1/16 to clarify ETV+’s viewership numbers.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|