02 Dec 15 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”What can’t people talk about? The latest magazine looks at taboos around the world”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

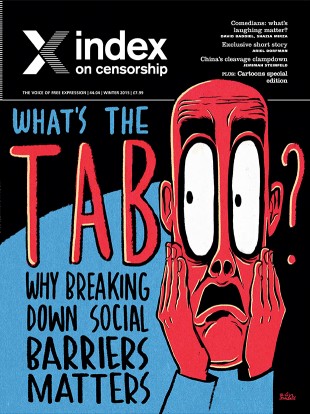

What’s taboo today? It might depend where you live, your culture, your religion, or who you’re talking to. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores worldwide taboos in all their guises, and why they matter. Comedians Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel look at tackling tricky subjects for laughs; Alastair Campbell explains why we can’t be silent on mental health; and Saudi Arabia’s first female feature-film director Haifaa Al Mansour speaks out on breaking boundaries with conservative audiences.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”60px”][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Plus a crackdown on porn and showing your cleavage in China; growing up in Germany with the ghosts of WW2; what you can and can’t say in Israel and Palestine; and the argument for not editing racism out of old films. As the anniversary of Charlie Hebdo murders approaches, we also have a special section of cartoonists from around the world who have drawn taboos from their homelands – from nudity, atheism and death to domestic violence and necrophilia.

Also in this issue, Mark Frary explores the secret algorithms controlling the news we see, Natasha Joseph interviews the Swaziland editor who took on the king and ended up in prison, and Duncan Tucker speaks to radio journalists who lost their jobs after investigating presidential property deals in Mexico.

And in our culture section, Chilean author Ariel Dorfman looks at the power of music as resistance in an exclusive short story, which is finally seeing the light after 50 years in the pipeline. We have fiction from young writers in Burma tackling changing rules in times of transition, and there’s newly translated poetry written from behind bars in Egypt, amid the continuing crackdown on peaceful protest.

Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: WHAT’S THE TABOO? ” css=”.vc_custom_1483453507335{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Why breaking down social barriers matters

Stand up to taboos – Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel on how comedy tackles the no-go subjects

The reel world – Nikki Baughan interviews female film directors Susanne Bier and Haifaa Al Mansour, from Denmark and Saudi Arabia

Not just hot air – Kaya Genç goes inside Turkey’s right-wing satire magazine Püff

Slam session – Péter Molnár speaks to fellow Hungarian slam poets about what they can and can’t say

Whereof we cannot speak – Regula Venske on growing up in Germany after WWII

China’s XXX factor – Jemimah Steinfeld investigates a crackdown on porn and cleavage

Pregnant, in danger and scared to speak – Nina Lakhani and Goretti Horgan on abortion laws and social stigma in El Salvador and Ireland

Airbrushing racism – Kunle Olulode explores the problems of erasing racist words from books and films

Why are we whispering? – Alastair Campbell on why discussing mental illness still makes some people uncomfortable

Shouting about sex (workers) – Ian Dunt looks at the debate where everyone wants to silence each other

The history man – Professor Mohammed Dajani Daoudi explains how he has no regrets, despite causing outrage after taking Palestinian students to Auschwitz

Provoking Putin – Oleg Kashin on how new laws are silencing Russians

Quiet zone: a global cartoon special – Featuring taboo-busting illustrations from Bonil, Dave Brown, Osama Eid Hajjaj, Fiestoforo, Ben Jennings, Khalil Rhaman, Martin Rowson, Brian John Spencer, Padrag Srbljanin, Toad and Vilma Vargas

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Reining in power – Natasha Joseph talks to the Swaziland editor who took on the king

Whose world are you watching? – Mark Frary explores the secret algorithms controlling the news we see

Bloggers behind bars – Ismail Einashe interviews Ethiopia’s Zone 9 bloggers

Mexican airwaves – Duncan Tucker speaks to radio journalists who were shut down after investigating presidential property deals

Head to head – Bassey Etim and Tom Slater debate whether website moderators are the new censors

Off the map – Irene Caselli on how some of the poorest people in Buenos Aires fought back against Argentina’s mainstream media

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The rocky road to transition – Ellen Wiles introduces new fiction by young Burmese writers Myay Hmone Lwin and Pandora

Sounds of solidarity – Chilean author Ariel Dorfman presents his short story on the power of music as resistance

Poetry from a prisoner – Omar Hazek shares his verses written in an Egyptian jail and translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Index on Censorship’s CEO, Jodie Ginsberg, on the pull between extremism legislation, free speech and terrorism

Index around the world – Josie Timms presents Index’s latest work and events

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

02 Dec 15 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015 Extras

Are there things that you just aren’t allowed to talk about at family gatherings over the holiday period? The forthcoming Winter 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine is exploring the subject of taboos and we want to hear what are the biggest taboos for discussion among your family and friends. Please fill in our international survey=.

In the magazine we’ve heard from writers all over the world: Jemimah Steinfeld investigates China’s crackdown on porn and cleavage; comedians Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel look at tackling tricky subjects in comedy; Kunle Olulode writes why he thinks racism shouldn’t be airbrushed from films; Alastair Campbell explains why we can’t be silent on mental health. Plus global cartoonists, including Osama Eid Hajjaj, Bonil, Martin Rowson and Dave Brown, illustrate a range of taboos, from domestic violence to nudity and death.

All these forbidden topics got the magazine team thinking — what are the subjects that we’ll be biting our tongues about at holiday gatherings? Don’t mention migrants around Uncle Seamus? Or equal rights around Uncle Jack? Will Auntie Mary be offended by your mentioning that you think that the royal family should pay tax? Or is no one allowed to mention that story about the cousin who ran away to join the circus?

Tell us your personal taboos.

Interested in global taboos? Order your copy of the magazine here, or take out a digital Christmas gift subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

[gravityform id=”16″ title=”false” description=”false”]

01 Dec 15 | Campaigns, Mapping Media Freedom, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

First as prime minister and now as president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been waging a methodical crackdown on the media in Turkey for years. Erdogan is persecuting journalists of all colours in an increasingly ferocious manner in the name of combatting terrorism and defending state security. The Erdogan regime’s arrests, threats and intimidation are unworthy of a democracy.

Can Dündar, the editor-in-chief of the Turkish daily Cumhuriyet, and his Ankara bureau chief, Erdem Gül, have been held since the evening of 26 November. They are charged with spying and terrorism because last May they published evidence of arms deliveries by the Turkish intelligence services to Islamist groups in Syria. Both are exemplars of journalism, the search for truth and the defence of freedoms. President Erdogan publicly said that Dündar “will pay for this.” But Cumhuriyet’s journalists just did their job, publishing information that was in the public interest.

At a time when international terrorism is at the centre of everyone’s concerns, it is unacceptable that political prosecutions are used to suppress investigative reporting and exposés. The arrest of these two journalists is the latest extreme to which political use of the Turkish judicial system has been taken. Many journalists have been detained on spurious charges of terrorist propaganda and insulting President Erdogan. The regime has also been using economic levers to put growing pressure on the media, while draconian laws have been passed.

We, public figures, media freedom NGOs and unions, reject the blatant erosion of media freedom in Turkey. The country is ranked 149th out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders press freedom index. Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project has recorded 178 verified reports of media violations since May 2014.

We appeal to the Turkish authorities to free Can Dündar and Erdem Gül without delay, to drop all charges against them, and to free all other journalists who are currently detained in connection with their journalism or the opinions they have expressed.

We also urge the institutions and governments of democratic countries to face up to their responsibilities to respond to President Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian excesses.

SIGNATORIES

Public figures

Günter Wallraff, journalist, Germany

Noam Chomsky, linguist, USA

Edgar Morin, sociologist, France

Carl Bernstein, journalist, USA

Zülfü Livaneli, writer, Turkey

Ali Dilem, cartoonist, Algeria

Thomas Piketty, economist, France

Claudia Roth, politician, Germany

Paul Steiger, journalist, United States

Kamel Labidi, journalist, Tunisia

John R McArthur, media executive, USA

Fazil Say, pianist, Turkey

Peter Price, media executive, USA

Edwy Plenel, media executive, France

Jim Hoagland, journalist, USA

Ahmet İnsel, political analyst, Turkey

Eric Chol, newspaper editor, France

Nedim Gürsel, writer, Turkey

Cem Özdemir, Green Party copresident, Germany

Hakan Günday, writer, Turkey

Mikis Theodorakis, composer, Greece

Per Westberg, writer, Sweden

Louise Belfrage, journalist, Sweden

Ali Anouzla, journalist, Morocco

Omar Bellouchet, journalist, Algeria

Jack Lang, former government minister, France

Omar Brouksy, journalist, Morocco

Pierre Haski, journalist, France

Jay Weissberg, cinema critic, USA

NGOs

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Committee to Project Journalists, (CPJ)

PEN International

International Press Institute (IPI)

World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WANIFRA)

Index on Censorship

World Press Freedom Committee (WPFC)

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Ethical Journalism Network (EJN)

Global Editors Network (GEN)

Turkish Association of Journalists (TGC)

Turkish Union of Journalists (TGS)

DISK Basinİş

Take action: Support the appeal by signing the petition in English, Turkish or French

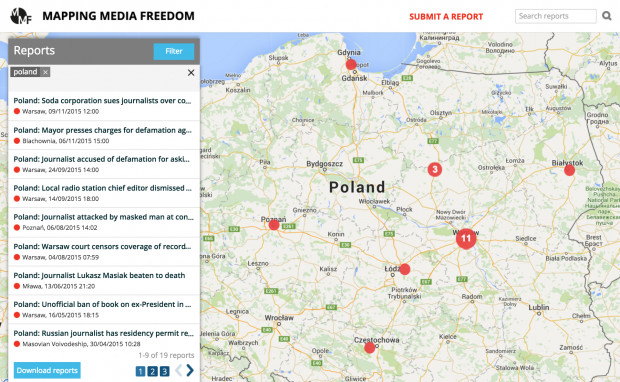

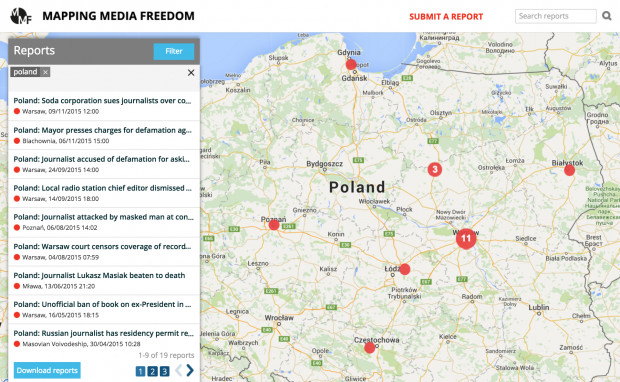

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

01 Dec 15 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Poland

Fact-checking is crucial for any piece of journalism. This was what the investigative journalist Jaroslaw Jakimczyk set out to do when he wrote an email to the press office at IT and technology company Qumak S.A. requesting authentication of information he had.

The company, which is based in Warsaw, provides information and communication services to well-known clients, such as the major Polish bank Pekao. Jakimczyk’s questions pertained to discs of private client data that, according to his information, there was proof of a transaction of sale between the two parties. When Jakimczyk received a response from Qumak’s press office in late September, the denial of any wrongdoing on their part was followed swiftly by something rather unexpected: Qumak was now pressing charges against Jakimczyk for defamation under article 212 of the Polish penal code.

Under article 212 of the Polish penal code, defamation is when one person defames another individual, group, company or association, over such characteristics “that might lower it in the public opinion or contribute to the loss of trust which is required for the office executed by it”. Defamation can be subject to up to a year’s imprisonment if “done through means of mass communication” under paragraph 2; without mass communication, one might just get away with a fine or, rather vaguely “limitations to freedom”. Until amendments were made to the law in 2010, imprisonment was a general possibility. A public apology is usually also a popular demand with any article 212 claim.

Defamation charges appear to have been keeping Polish judges increasingly busy over the years: The Helsinki Foundation of Human Rights, in its publication on article 212, points out that while 43 article 212 claims were put forward in 2000, by 2011, this figure had risen to 232. At times, the entire Polish judicial system is exhausted. This happened to Andrzej Marek in 2004, who had accused a local politician of corruption in an article, and Marian Maciejewski, who had written articles critical of judicial inaccuracies in the city of Wroclaw.

In both instances, defamation charges were pressed, and both cases took years to reach the European Court of Human Rights to be ruled breaches of article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which deals with free expression. The court ordered compensation payments for the journalists. Five more very similar cases were rejected by European Convention in the same way. But article 212 claims continue to dog journalists.

A part in the explanation for the increase of claims lies, for multiple reasons, with the internet. As Dorota Glowacka, an expert on 212 at the Helsinki Human Rights Foundation, told Index on Censorship, the fact that information is online might instill a heightened sense of urgency in potential claimants, as “the statements would be perceived as more harmful to their reputation, due to them remaining ‘online forever’”. Paradoxically, the accessibility of information through the web, according to Jakimczyk, might also work against them: “Many representatives of local oligarchies who read and analyse online publications on the subject have come to the somewhat correct conclusion that there are means to silence uncomfortable journalists.”

A review of cases of journalists charged with article 212 shows that local authorities are often involved. Earlier this month, the mayor of the small municipality in south-east Poland, Blachownia, decided to press charges against the editor-in-chief of a critical independent local news portal. As Jakimczyk noted, “previously, many of those based in Polish provinces had not heard of such a possibility or did not have enough courage to go ahead with them”, but the “amplification of cases charged with article 212 might have encouraged them to take up the same”.

In fact, council authorities sometimes press charges under 212 on behalf of a criticised local politician, arguing that such criticism “hits the good reputation of the whole council”, as Glowacka said. Such cases are rather comfortable arrangements for the politicians, as it involves no expenditures or extra efforts of their own: they can make use of the council’s legal services, and any costs relating to the case will be paid for.

Glowacka said that the cases reaching the attention of the Helsinki Human Rights Foundation have still largely been those of journalists and political activists. Increasingly, though, even the average citizen leaving a negative product or brand review, might get sued for defamation. And if comments are left anonymously, then article 212, as part of the criminal code, guarantees police support in subject identification; if one were to consider taking up the alternative route through the civilian code that also protects personal goods and good reputation, this possibility does not exist.

Attempts to strike the article from the criminal code have come from many angles over the years: between 2007 and 2012, the OSCE, the Council of Europe, as well as freedom of speech and human rights delegates of the UN openly criticised the article for curtailing freedom of speech. The diplomat Irina Lipowicz had challenged the possibility of imprisonment for defamation before the Polish Constitutional court three years ago, but that only pointed to its 2006-ruling, when it was decided article 212 did not infringe upon freedom of speech.

In 2011, the Polish citizen Mariusz S. filed a petition to remove 212 from the Polish criminal code, but the voting did not bring about a clear majority and the provision remained in place. The Helsinki Human Rights Foundation, in the run-up to the 2011 national parliamentary elections, promoted a large-scale campaign to ‘Erase article 212’. At the time, 140 Polish MPs declared they would support a move to drop the defamation clause.

It appears, though, that there is a lack of substantial, genuine political will, and that, too often, it presents itself as a handy “whip” or looming “sword of Damocles”, Glowacka and Jakimczyk said. The former points to an illustrative example of the Polish People’s Party [org.: Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe], which officially backed the Erase initiative in 2011, only for its vice chair Eugeniusz Grzeszczak to put forward claims against journalists in his constituency a year later, when he disagreed with their revealing his payments to a favourable publisher. For Polish politicians to truly find interest in removing the provision, “an incident would be needed of accusations on article 212 pressed against a representative of this very class, which appears to consider itself as a club of untouchables”, Jakimczyck commented.

The journalist underscored another, deeper issue that the threat of defamation charges makes possible. The ties between business and media publishers are close to the extent that they lead to “the introduction of unwritten rules, limiting or excluding publication of critical material on certain companies, corporations or public institutions, which have a large advertising budget to their disposal.” It does not seem a coincidence that critical material has been increasingly held back, especially since the financial crisis in 2008, he said.

In Jakimczyck’s experience, this has pertained to any reports on firms which the state treasury has shares in, including major names such as the largest Polish insurance firm PZU, the copper and silver production company KGHM Polska Miedz, the Polish oil refiner and retailer Orlen, as well as the Polish Energy Group. Every time an article remained unpublished, “never did those responsible [at the paper in question] provide a satisfactory justification as to why publication was denied”. The incident with Qumak’s charges, tied budget-wise to the largest Polish bank, is no longer an isolated incident so much as “the further logical consequence of the new phenomenon that is preventive censorship”. Worryingly, these are not publicly accountable institutions but rather in the hand of “private capital that is not subject to societal checks and balances”.

Jakimczyk’s case, in the meantime, appears resolved: in a court ruling earlier this month, judges found that to qualify for defamation, the content in question has to have at least been shared with one other person; judges have also raised the crucial point that a journalist’s main role is to ask questions, i.e.: the journalist was just doing his job. Qumak S.A. will now have to cover any resulting fees for courts.

Although the company is legally entitled to claim revision, for the sake of the state of journalism in Poland, it is hoped that this case will remain at that, and set an ultimate example what worrying direction alleged defamation charges should stop going to in Poland.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

30 Nov 15 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

Index on Censorship condemns the killing of Turkish human rights lawyer Tahir Elci, who was shot during a press conference on Saturday.

Elci, was briefly detained and questioned last month for saying during a live news program that the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, is not a terrorist organisation. According to The Guardian newspaper, he was charged soon after with making terrorist propaganda and was facing more than seven years in prison.

The human rights defender was the lawyer for Mohammed Rasool, a journalist with Vice News, who remains in prison awaiting trial on charges of aiding a terrorist organisation.

The shooting comes amid a rapid deterioration for free expression in Turkey. Index on Censorship was part of a delegation to the country last month that met officials and journalists including Can Dundar, editor-in-chief of Turkish daily newspaper Cumhuriyet.

Can Dundar and Erdem Gul, the newspaper’s Ankara bureau chief, were both arrested and charged last week with aiding an armed terrorist organisation.

“Index condemns the murder of Tahir Elci and urges the Turkish authorities to fulfil its democratic obligations to protect the legal and media professions. We also ask the European Union to do more to hold Turkey, which seeks membership of the EU, to account,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

Turkey’s deterioration has been documented by Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project, which monitors media violations across Europe. There have been 177 verified reports in the country since the map was launched in May 2014.

30 Nov 15 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns, Statements

Intigam Aliyev

Intigam Aliyev, a human rights defender and a lawyer who specialised in defending the rights of Azerbaijani citizens before the European Court of Human Rights, is spending his second birthday in prison.

“All our thoughts are with Intigam as he spends yet another birthday in jail,” Index on Censorship senior advocacy officer Melody Patry said.

In April 2015, Aliyev was sentenced to 7.5 years imprisonment for illegal business activities, tax evasion and abuse of power. The case was widely condemned as being politically motivated by Azerbaijan’s government.

Aliyev, who ran the Azerbaijan-base Legal Research Institute, was one of a score of prominent human rights activists and journalists who were arrested and subjected to show trials in 2014 and 2015. A new report details the judicial harassment that Azerbaijan’s civil society has been subjected to.

Take action: Send your birthday wishes to Intigam Aliyev

27 Nov 15 | Campaigns, Middle East and North Africa, mobile, Palestine, Statements

We, the undersigned organisations, all dedicated to the value of creative freedom, are writing to express our grave concern that Ashraf Fayadh has been sentenced to death for apostasy.

Ashraf Fayadh, a poet, artist, curator, and member of British-Saudi art organisation Edge of Arabia, was first detained in August 2013 in relation to his collection of poems Instructions Within following the submission of a complaint to the Saudi Committee for the Promotion of Virtue. He was released on bail but rearrested in January 2014.

According to court documents, in May 2014 the General Court of Abha found proof that Fayadh had committed apostasy (ridda) but had repented for it. The charge of apostasy was dropped, but he was nevertheless sentenced to four years in prison and 800 lashes in relation to numerous charges related to blasphemy.

At Ashraf Fayadh’s retrial in November 2015 the judge reversed the previous ruling, declaring that repentance was not enough to avoid the death penalty. We believe that all charges against him should have been dropped entirely, and are appalled that Fayadh has instead been sentenced to death for apostasy, simply for exercising his rights to freedom of expression and freedom of belief.

As a member of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), the pre-eminent intergovernmental body tasked with protecting and promoting human rights, and the Chair of the HRC’s Consultative Group, Saudi Arabia purports to uphold and respect the highest standards of human rights. However, the decision of the court is a clear violation of the internationally recognised rights to freedom of conscience and expression. Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) states that, “[e]veryone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief”. Furthermore, under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”. Saudi Arabia is therefore in absolute contravention of the rights that as a member of the UN HRC it has committed to protect.

There are also widespread concerns over an apparent lack of due process in the trial: Fayadh was denied legal representation, reportedly as a result of his ID having been confiscated following his arrest in January 2014. It is our understanding that Fayadh has 30 days to appeal this latest ruling, and we urge the authorities to allow him access to the lawyer of his choice.

We call on the Saudi authorities to release Ashraf Fayadh and others detained in Saudi Arabia in violation of their right to freedom of expression immediately and unconditionally.

List of signatories:

AICA (International Association of Art Critics)

Algerian PEN

All-India PEN

Amnesty International UK

Arterial Network

ARTICLE 19

Artists for Palestine UK

Austrian PEN

Banipal

Bangladesh PEN

Bread and Roses TV

British Humanist Association

Bulgarian PEN

Centre for Secular Space

CIMAM (International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art)

Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain

Croatian PEN

Crossway Foundation

Danish PEN

English PEN

Ethiopian PEN-in-Exile

FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights)

Five Leaves Publications

Freemuse

German PEN

Haitian PEN

Human Rights Watch

Index on Censorship

International Humanist and Ethical Union

Iranian PEN in Exile

Jimmy Wales Foundation

Lebanese PEN

Ledbury Poetry Festival

Lithuanian PEN

Modern Poetry in Translation

National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC)

Norwegian PEN

One Darnley Road

One Law for All

Palestinian PEN

PEN American Center

PEN Canada

PEN International

PEN South Africa

Peruvian PEN

Peter Tatchell Foundation

Portuguese PEN

Québec PEN

Russian PEN

San Miguel PEN

Scottish PEN

Slovene PEN

Society of Authors

South African PEN

Split This Rock

Suisse Romand PEN

School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing, University of East Anglia

The Voice Project

Trieste PEN

Turkish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

27 Nov 15 | Europe and Central Asia, France, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Editorial Credit: Frederic Legrand – COMEO / Shutterstock.com

Even before the attacks on Paris on 13 November were over, French President Francois Hollande declared a nationwide state of emergency giving authorities additional powers in the name of protecting citizens and combatting terrorism. But since the attacks, concerns have been raised for press freedom prompted by the cancellation of a regular radio segment by journalist Thomas Guénolé.

A few days after the events of 13 November, Guénolé devoted his daily morning commentary piece on RMC radio to what he perceived as the failings of the French security services and police. On the same day, the Interior Ministry called Philippe Antoine, RMC managing editor, to demand the radio station air a corrective to points Guénolé discussed during his segment, which the ministry would pen. “Interestingly, the corrective was not going to appear as a corrective emanating from the Interior Ministry but as the correction of an inaccurate information emanating from RMC,” Guénolé told me.

The proposed corrections were in relation to Guénolé’s discussion of claims reported by various news outlets, including that France had known since August 2015 that IS planned to attack a rock concert in France and that Turkish authorities had warned France twice this year about Omar Ismaïl Mostefaï, one of the assailants of the Bataclan massacre.

Guénolé called for a parliamentary investigation which should, if these claims were true, prompt the resignation of the highest ranking French officials, including Bernard Cazeneuve, France’s Minister of the Interior.

Guénolé also repeated information published by La Lettre A, which claimed only three out of 50 members of the Parisian Brigade de recherche et d’intervention (an anti-gang unit, which is to intervene in hostage situations) had been on duty after 8pm on the night of the attacks. On 19 November, the special adviser to France’s interior minister, Marie-Emmanuelle Assidon, took to Twitter to say the information contained in La Lettre A was false but recognised she had not read the article. “[N]o one but Thomas Guénolé trusts your info,” she added in her tweet.

“I have repeatedly asked Place Beauvau for a denial,” Marion Deye, editor at La Lettre A, told me. “I haven’t had one.” Neither have Le Monde or the AFP, also quoted by Guénolé.

“We published a very factual piece of news on the Monday following the attacks, at a time when any type of criticism was not welcome,” Daye said. “However, what we published was not a criticism, just a report. The most absurd thing in this whole story is that no one knows what Place Beauvau denied when they spoke to RMC. I think what was really problematic for some was that Guénolé brought up the resignation of Cazeneuve.”

On Friday 20 November, Guénolé was informed that his daily column was cancelled. In an email, the RMC managing editor wrote: “The Interior Ministry and all the police services invited on air have refused to appear on RMC because of inaccuracies in your column. Most sources of our police specialists have gone silent since Tuesday, putting in jeopardy the work that our editorial team does to find and verify information.”

Guénolé described the actions against him as both a “boycott” and an “embargo”.

“One would expect a media outlet to back up its journalist and not to have too strong a dependency vis-à-vis institutions,” he said. “My particular case doesn’t matter so much. What is unacceptable is that the Interior Ministry seems to have pressured RMC because they were displeased with what a journalist said on air in the context of the state of emergency.”

The firing of Guénolé happened on the on the same day the Assemblée Nationale voted to extend the state of emergency from 12 days to three months. Measures to control the press were initially proposed by 20 socialist MPs led by Sandrine Mazetier on the basis that the coverage of the January 2015 attacks in Paris – especially by news channel BFM-TV – had endangered the life of hostages who were hiding in a Hyper Casher supermarket. Such a measure would be highly problematic. As Mathieu Magnaudeix, a journalist with the investigative website Mediapart, put it to me: “If we were to end up with an authoritarian power, which by now doesn’t seem to be out of the question, what could they do with a law that allows the control of the press?”

Thankfully, the press control measures were later dismissed and it was made clear that even Hollande was strongly opposed. Regardless, it is apparent journalists still aren’t safe.

The proposed law does, however, extend and harden house arrests that are allowed under a state of emergency, enables members of the police force to carry their weapons while off duty, gives stronger powers to the authorities to carry police searches that are not approved by a judge. While these cannot be carried out in the workplace, police searches can take place at the house of an MP, lawyer, a judge or a journalist.

This kind of anti-terror legislation, as we have seen in the UK, could have further negative consequences for journalists covering terrorism.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

26 Nov 15 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

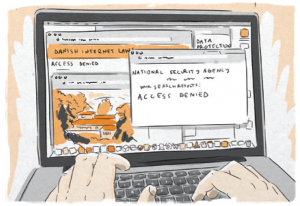

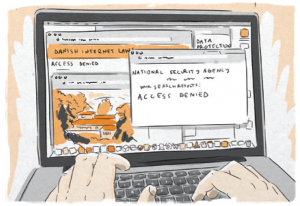

A new graphic novel exploring challenges to press freedom across Europe and the impact of limitations on journalists has been released by the European Youth Press.

A new graphic novel exploring challenges to press freedom across Europe and the impact of limitations on journalists has been released by the European Youth Press.

Free Our Media is the result of a collaborative effort over the course of several months by a team of young journalists and illustrators assembled from all over Europe by European Youth Press, and contains 14 comics, each story centred on the state of media freedom in a different country. The project was funded by the Council of Europe.

Planning for Free Our Media started in autumn of 2014, when the European Youth Press team began outlining which media advocacy issues the organisation would focus on in 2015. Press freedom was high on the list of priorities, given its recent deterioration in the EU and neighbouring countries, and the organisation’s resolve to tackle this particular issue was only heightened by the violent attacks on satirical French newspaper Charlie Hebdo in January 2015. The visual medium of the graphic novel was chosen in order to make the content more universal across borders and language barriers.

“A written article would get shared by an audience that is already familiar with the topic of press freedom,” said European Youth Press board member and Free Our Media project coordinator Anna Saraste. “In the comic book, we communicate the topic with a visual medium that appeals to a broader public.”

“A written article would get shared by an audience that is already familiar with the topic of press freedom,” said European Youth Press board member and Free Our Media project coordinator Anna Saraste. “In the comic book, we communicate the topic with a visual medium that appeals to a broader public.”

Creating the graphic novel was a challenge from start to finish, not least because of the distance between the participants. The journalists, who are aged between 18 and 35 and collectively dubbed Media Freedom Ambassadors, met twice before the final workshop. During these events, the group developed tools for actively addressing limitations to press freedom. They also had the opportunity to organise events within their own communities, which allowed them to gather input from other journalists and young media makers about press freedom and its value in society.

Months of work culminated in Berlin in July 2015. During a five-day workshop led by artists Yorgos Konstantinou and Marcos Mazzoni, the group of journalists met with the cartoonists and, in pairs, planned the storylines for each comic. Following the end of the workshop, the group worked on their pieces separately, and kept each other updated on their progress via Facebook and Skype, said Jo Breese, a British illustrator and Sunday Times graphic artist who was selected as one of the cartoonists for Free Our Media.

“You can draw silly cartoons about serious matters, and it helps, and it gets the message across,” Breese said. “And I think that was important for a lot of the people who were there, whose countries don’t have very good press freedom. It gave them a platform to say what they wanted to say.”

The book’s varied stories and illustration styles made the creation of a cohesive graphic novel another significant challenge. The solution devised by the team was a common color scheme throughout, comprised of various shades of white, black, and orange.

The completed graphic novel was officially released at the European Youth Media Days that took place in the European Parliament in Brussels from 20-22 October. Because the European Youth Press is a non-profit organisation, they must rely on donations to print, but soon hope to be able to start selling copies of the book online. While the book itself is a valuable tool for combating limitations on press freedom in Europe, Saraste is quick to emphasise that the real agents of change are young media makers.

“I wouldn’t focus so much on the book. I think what will be impacted for a long time are the ambassadors,” she said. “I think a lot has changed for them in terms of how they see their role as young media makers. Something in their attitude changed. They will have an impact on other people, wherever they go and wherever they decide to practice this profession.”

Following the completion of Free Our Media, the Media Freedom Ambassadors are continuing their activism by blogging for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project, to which they will contribute reports about their own countries and act as references for the site.

You can preview the graphic novel here.

This article was published on 26 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Nov 15 | mobile, News and features, South Africa

The media does not care about us, they never report things relevant to us and papers are only interested if there is bad news about us, the elderly, gap-toothed man says.

The digital revolution is also passing his community by, he adds. His deeply lined face and brow offer testimony to his day-to-day battle to eke out a life in the “temporary relocation area” of Blikkiesdorp, where many of Cape Town’s disenfranchised have washed up.

“Internet is expensive and doesn’t work well there, and there’s nothing in the papers that talks to us and about our struggle and lives. It’s like we don’t exist.”

The man is an “ordinary citizen” who took part in last weekend’s Cape Town leg of a countrywide series of Media Transformation and Right to Communicate summits organised by the Right2Know Campaign.

“As inequality deepens and social cohesion falters, South Africa needs a media that can offer expression to the full range of voices and facilitate the substantive and complex debates about the social and economic future of the country,” says Mark Weinberg, national coordinator of R2K.

Issues on the agenda include the need for a free and diverse press, the concentration of ownership of South Africa’s media in the hands of four dominant players and the ongoing political interference in the affairs of the SABC, as the ANC tightens its control of the state broadcaster. Participants also voiced concerns at the slow pace of South Africa’s transition to digital terrestrial TV, which will free up bandwidth for high-speed internet and new independent radio and TV stations.

During one session, a community journalist from one of Cape Town’s poorest townships angrily berated the big media houses and called on his “comrades” to march on their offices to “force” them to fund smaller, struggling independent media. Around the room, I noted many others nodding in agreement.

The anger at a perceived lack of transformation in the country’s media is fueled by the fact that the print media is still largely dominated by a handful of powerful companies, even though the landscape has shifted since the birth of a new, democratic South Africa in 1994. The anger was not only aimed at big media houses which stand accused of using predatory pricing tactics to force smaller, less well-resourced outlets out of business.

Participants also had their sights firmly set on government and its failure to support independent community print and radio. Often the main source of income for some small media is paid-for government advertorial, another participant pointed out. The result is that recipients of this revenue are reluctant to rock the boat and report critical stories about government for fear of losing this vital income.

The summits come against the backdrop of a new push by the government to introduce a Media Appeals Tribunal amidst ongoing reporting by South African media on corruption and the squandering of taxpayer money as the economy contracts, raising fears of recession.

William Bird, the head of Media Monitoring Africa says the Media Appeals Tribunal “is bad because, aside from the potential limitations to freedom of expression, it simply won’t address the core concerns over the quality of news content, diversity, transformation and what some perceive as overly negative coverage”.

As a journalist, I was often taken aback during the course of the summit at the depth of anger and isolation felt by ordinary people, especially those from poor communities who felt the media serves the rich and that they are denied a voice.

Nevertheless, I left the summit feeling hopeful. The passion of the man from Blikkiesdorp and others like him and their determination to take the fight to big media and government help remind me that while South Africa may have problems, our democracy remains strong and robust.

This column was posted on 26 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Nov 15 | Asia and Pacific, Malaysia, mobile, News and features

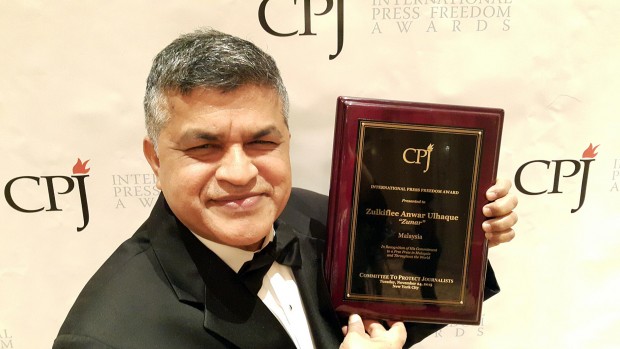

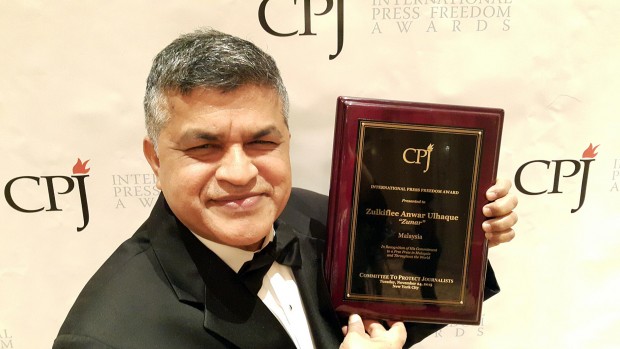

Zunar with his International Press Freedom Award

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar has won the International Press Freedom Award 2015 from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

The political cartoonist, who uses his work to expose abuses of power and corruption in Malaysia, was presented the award yesterday evening at a gala dinner at The Waldorf Astoria, New York.

In his acceptance speech, Zunar dedicated the award to “the Malaysians who have equally pushed for reform”. He also took the opportunity to criticise the Malaysian government: “It is both my responsibility and my right as a citizen to expose corruption, wrong-doing and injustices. Laws like the Sedition Act mean that drawing cartoons is a crime.”

“The government of Malaysia is a cartoon government; a government of the cartoon, by the cartoon, for the cartoon — sorry Abraham Lincoln,” Zunar joked. “For asking people to laugh at the government, I was handcuffed, detained, thrown into the lock-up. But I kept laughing and encouraging people to laugh with me. Why? Because laughter is the best form of protest.”

Zunar currently faces 43 years in prison on nine separate charges of sedition for tweets he wrote criticising Malaysia’s judiciary over the incarceration of a Malaysian opposition leader. His court case was due to begin on 6 November. However, the cartoonist and his lawyers applied to have the case referred to the High Court, delaying proceedings. The application is set for a hearing on 8 December.

The threat of imprisonment obviously hasn’t deterred him from continuing with his work. “My mission is to fight through cartoons,” Zunar said. “Why pinch when you can punch? People need to know the truth and I will continue to fight through my cartoons. I want to give a clear message to the aggressors — they can ban my cartoons, they can ban my books, but they cannot ban my mind.”

Four of Zunar’s most celebrated cartoons are on display at London’s Cartoon Museum until January.

This article was posted on 25 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Nov 15 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Photographer Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi

Award-winning photographer Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi was sentenced on Monday, 23 November 2015, to 10 years in prison and had his nationality revoked, along with 12 others, after covering a series of demonstrations in early 2014. Security forces detained Al-Mousawi for over a year without trial or official charges, accused him of being a part of a terrorist cell and subjected him to torture. The undersigned NGOs condemn the government’s continued attacks on independent journalism, policy of media censorship and severe restrictions on freedom of expression in Bahrain.

Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi, a winner of 127 international photography awards, has been incarcerated since his arrest on 10 February 2014, when security forces raided his home in Duraz village. According to al-Mousawi’s father, a group of plainclothes masked policemen arrested Sayed Ahmed and his brother. The police provided no arrest warrant and confiscated al-Mousawi’s cameras and electronic devices. Al-Mousawi alleges that he was tortured during his detention and interrogation.

Al-Mousawi’s torture follows a pattern of abuse Human Rights Watch documented in a new report released on 24 November on the ongoing use of torture in Bahraini police detention and prison. Police disappeared and tortured al-Mousawi for five days, subjecting him to severe beatings on his genitals, electrocution and hanging from a door. For the duration of his disappearance, he was stripped naked and forced to stand for long periods of time. Officers did not allow a lawyer to accompany al-Mousawi when they transferred him to the Public Prosecutor. Courts renewed al-Mousawi’s pre-trial detention six times, and he spent over a year in prison without formal charges.

“Sayed al-Mousawi’s torture took place at a time when the UK has been increasing its spending on a ‘reform programme’ for Bahrain to bolster its institutions,” said Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy at BIRD. “It is becoming increasingly clear that this programme has failed. Torture is still systematic and unrelenting and the government has broken all promises of reform.”

During his extended detention, al-Mousawi continued to win international awards for his photography. In spite of this, the government accused him of giving SIM cards to “terrorist” demonstrators and taking photos of anti-government protests. As a result, Bahrain tried al-Mousawi under Bahrain’s vague anti-terrorism legislation. A judge later accused him and his brother of membership in a terrorist cell, which al-Mousawi continues to deny.

“Al-Mousawi’s case exposes Bahrain’s continued misapplication of its counterterrorism law to hide evidence of its human rights abuses,” said Husain Abdulla the Executive Director of ADHRB. “Taking photos of peaceful protestors is not a crime and Bahrain’s overreaction shows just how fearful the Bahraini government is of its own people.”

Bahrain’s continued arrest of journalists and photographers, who expose human rights violations, reflects a systematic campaign by the authorities to quell freedom of expression and the press. Bahrain is ranked 163 out of 180 in the 2015 World Press Freedom Index according to Reporters Without Borders. Last year, a Bahraini court also convicted another renowned photojournalist, Ahmed al-Humaidan to 10 years in prison under similar charges. Bahrain has revoked the citizenship of more than 130 individuals since 2012.

“Yet again the Bahraini government has wielded citizenship as a weapon of censorship against journalists,” said CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa program coordinator, Sherif Mansour. “We call on the Bahraini judiciary to overturn this disturbing sentence, recognize al-Mousawi’s citizenship, and free him immediately.”

We, the undersigned NGOs, call for the immediate release of Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi, and on Bahrain to end the criminalization of free speech and press. We also call on the UK government to suspend its spending on technical assistance to Bahrain, and on the US government to reinstate the ban on arms sales to the country, until systematic torture has been eradicated and restrictions on the enjoyment of internationally-codified human rights are lifted.

Sincerely,

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Index on Censorship

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

A new graphic novel exploring challenges to press freedom across Europe and the impact of limitations on journalists has been released by the

A new graphic novel exploring challenges to press freedom across Europe and the impact of limitations on journalists has been released by the  “A written article would get shared by an audience that is already familiar with the topic of press freedom,” said European Youth Press board member and Free Our Media project coordinator Anna Saraste. “In the comic book, we communicate the topic with a visual medium that appeals to a broader public.”

“A written article would get shared by an audience that is already familiar with the topic of press freedom,” said European Youth Press board member and Free Our Media project coordinator Anna Saraste. “In the comic book, we communicate the topic with a visual medium that appeals to a broader public.”