13 Oct 15 | Events, mobile

Structured around and spurred on by the spirit of interrogation, Question Everything is an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia.

Are we in a drought of new options? Start imagining the world anew with a series of dissident provocateurs asking challenging questions and interrogating the opinions we trust, the systems which govern us and the things we take for granted.

Dissent encouraged. Be prepared not to agree.

With dissenters including:

• Brett Scott (author of The Heretic’s Guide to Global Finance).

• Ellen Quigley (University of Cambridge Ethical Investment Working Group).

• Francesca Martinez (comedian).

• Gary Anderson & Lena Simic (artists, The Institute for the Art and Practice of Dissent at Home)

• Hamid Ismailov (Uzbek journalist and writer).

• Heydon Prowse (satirist, The Revolution Will Be Televised)

• Mel Evans (author of Artwash: Big Oil and The Arts, activist Platform London & Liberate Tate).

• Noemi Lakmaier (artist).

• Peter Tatchell (activist).

• Tassos Stevens (artist, Coney).

• Priyamvada Gopal (Faculty of English, Cambridge).

• Thomas Jeffrey Miley (Department of Sociology, Cambridge).

Compered by Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship.

When: Sunday 25 October, 1:00pm – 6:00pm

Where: Cambridge Junction, Clifton Way, CB1 7GX (Map)

Tickets: £5 from Cambridge Junction

Question Everything is a highlight of the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, which has the theme of ‘power and resistance’. This event is a co-production by Index on Censorship, the Junction Cambridge and Cambridge Festival of Ideas.

12 Oct 15 | mobile, News and features, United States

|

Battle of Ideas 2015

A weekend of thought-provoking public debate taking place on 17 & 18 October at the Barbican Centre. Join the main debates or satellite events.

The Birth of a Nation: more than racism on film?

What we do we make of the film today? Does the current reaction to it mirror contemporary controversies about free speech and the arts? Dr Graham Barnfield, Jenny Barrett, Nadia Denton, Kunle Olulode and Dr Melvyn Stokes with chair Nathalie Rothschild. Battle of Ideas festival.

When: 17 October, 2-3:30pm

Where: Cinema 2, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas

• Full details

After Ferguson: policing and race in America

Kunle Olulode will also be part of a panel chaired by Jean Smith with Dr James Campbell, Dr Anna Hartnell, Dr Kevin Yuill at Battle of Ideas festival.

When: 17 October, 10-11:30am

Where: Pit Theatre, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas

• Full details

Artistic expression: where should we draw the line?

Join Manick Govinda, Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg, Cressida Brown, Nadia Latif, Nikola Matisic with chair Claire Fox at the Battle of Ideas festival.

When: 17 October, 4-5:15pm

Where: Cinema 2, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas

• Full details |

“Why censor the motion picture — the labouring man’s university? Fortunes are spent every year in our country teaching the truths of history, that we may learn from the mistakes of the past a better way for the present and future. The truths of history today are restricted to the limited few attending our colleges and universities; the motion picture can carry these truths to the entire world, without cost, while at the same time bringing diversion to the masses. As tolerance would then be compelled to give way before knowledge and the deadly monotomy of the cheerless existence of millions would be brightened by this new art, two of the chief causes making war possible would be removed.”

So wrote DW Griffiths in 1916 in the aftermath of his epic film Birth of a Nation. Fine words, loaded with twisted assumptions that rankle, irritate and anger anti-racists even a century on.

Birth of a Nation is no ordinary film. Inspired by Reverend Thomas Dixon’s novel and play The Clansman, it was engulfed in controversy: its central theme championed the post-civil war reformation of the Klu Klux Klan and blatantly suggested that American society only functioned effectively through the subjection of its black population. Worse still, its depiction of the defeated white slave-owning class as honourable victims of corrupt northern unionists and ‘carpet baggers’ contrasted against newly-liberated former slaves as feral, lustful, illiterates drunk with power and indulging in legally-sanctioned excess and wanton violence mainly to force white women into sexual relations.

Not surprisingly, on its release it was attacked by black journalists, political campaigners, trade unions, local government and filmmakers. The then newly-formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People lead a national campaign against it. In total, the film was banned in five states and 19 cities. Even as late as 1946, the Museum of Modern Art in New York refused to screen it.

Protests and audience reaction to the film, for and against, led to violent and, in some cases, fatal clashes. This continued right up to the 1950s when rumours of a talking re-make of the film swept Hollywood, reactivating the muted echo of labour union protests from earlier years.

In the 1980s, film historian Donald Bogle put forward the theses that film effectively shaped the images of black characters in Hollywood by consolidating five stereotypes: the Uncle Tom, the Comical Coon, the Tragic Mulatto, the Sexless Mammy and the over-sexed and violent Big Buck. These are ideas that would later be taken up by Robert Townsend in his comedic Hollywood Shuffle and more recently in Spike Lee’s polemic Bamboozled.

Nevertheless, Birth of a Nation was both a commercial and artistic success. Superbly directed by Griffiths, it altered the entire course of filmmaking, utilising innovative filming techniques such as close-ups, track shots and cross-cutting action sequences. The film initially made the relatively huge sum of $100,000 and earned over $18 million by 1931. It was only superseded by Gone With the Wind, another slavery epic that took its cue directly from Griffiths’ work. By the time of World War II, it had been seen by over 200 million people worldwide.

But that still doesn’t fully explain why the scope of Griffith’s work continues to trouble critics, filmmakers and fans alike. One of the best responses to this dilemma came from Richard Brody when he wrote in the New Yorker that, “the movie’s fabricated events shouldn’t lead any viewer to deny the historical facts of slavery and Reconstruction. But they also shouldn’t lead to a denial of the peculiar, disturbingly exalted beauty of Birth of a Nation, even in its depiction of immoral actions and its realisation of blatant propaganda.”

But the denial he seeks to avoid has already happened. The fact that the 100th anniversary of the film this year has been so studiously avoided by Hollywood and the Golden Globes Awards speaks volumes of its enduring power to shock, and the discomfort of both the film world and America more generally with confronting its troubled past when it comes to race and prejudice.

Attempting to understand and explore the social context in which racist ideas come from appears — in the 21st century — to have become a more difficult and exceptional task. Sadly, it seems that many would prefer airbrushing them away: deciding it’s better that people, in particular black people and those white masses ‘susceptible’ to racist ideas, avoid being exposed to the uncomfortable realities of the past.

However, we also have the examples of unheralded but important black filmmakers such as Oscar Micheaux who didn’t back off from these challenges, but set about confronting the issues that agitated black and white audiences by telling alternative stories. In 1920, he created and produced Within Our Gates, a direct rebuttal to Griffiths’ propaganda. Micheaux’s emergence represents the first radical black voice in American film.

Kunle Olulode is director of Voice4Change England and film historian. He is speaking on Birth Of A Nation: more than racism on film? at the Battle of Ideas festival at the Barbican on 17 October. Index on Censorship’s director Jodie Ginsberg is also speaking on a session entitled Artistic expression: where should we draw the line?. Index are media partners of the festival.

09 Oct 15 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Russia

The return of Vladimir Putin as president of the Russian Federation in 2012, after a wave of protests, was followed by the implementation of a new law that required non-governmental organisations receiving foreign support — in the form of funding or material aid — and engaged in “political activity” to register as “foreign agents” with the Ministry of Justice.

There are currently eight organisations advocating for media freedom and journalists’ rights included on a black list of 86 NGOs. Among them are organisations fighting for access to information (Freedom of Information Foundation), providing legal support to journalists (Rights of the Media Defence Centre and Media Support Foundation (Sreda)), organising education for regional reporters (Press Development Institute – Sibir in Novosibirsk and Regional Press Institute), an information agency (Memo.ru) and others.

Foreign agents have additional responsibilities and duties, including having to report twice as often and providing more information to the Ministry of Justice than other NGOs. A notice reading “Published by an NGO – foreign agent” must mark everything they publish, although some refuse to comply. In the Russian language, “foreign agent” has strong negative connotations associated with Joseph Stalin’s Soviet-era political repression. Some would say the term implies that NGOs are spies or traitors.

Only one organisation in Russia had voluntarily identified itself as a foreign agent before July 2014 when new rules allowed the Ministry of Justice to put NGOs on the list as it sees fit.

Some of the media freedom organisations are in the process of shutting down, including Sreda and Freedom of Information Foundation, while others, such as the Regional Press Institute (RPI) in St Petersburg, continue their activities but are forced to pay large fines.

Anna Sharogradskaya, the director of RPI, says she would never register the NGO voluntarily. “Article 51 of the Russian constitution says that nobody is obliged to give incriminating evidence against himself or herself and labeling the RPI would be not only incriminating evidence, it would be slander on our donors,” Sharogradskaya says. “So why should I break the law?”

Since 1993, RPI has provided seminars for journalists from Russia’s northwest region, offered its facilities as a venue for independent press conferences and meetings, and organised discussions on topical issues.

The organisation has come under increasing state pressure. In June 2014, customs officers at the Pulkovo International Airport in St Petersburg detained Sharogradskaya and searched her luggage. She missed her flight to the USA where she had been visiting scholar at Indiana University. Her notebook, memory stick and other gadgets were confiscated without explanation. For more than 10 months, Sharogradskaya was suspected of terrorism and extremism, after which she was cleared of all charges and her belongings were returned — although not in working order.

In November 2014, Putin promised that the St Petersburg regional Ombudsman Alexander Shishlov would look into the RPI case. “And he did: some days after this meeting, the Ministry of Justice put my organisation on the list of foreign agents,” says Sharogradskaya.

A court in St Petersburg fined RPI 400,000 rubles ($6,150) for refusing of add itself to the list voluntary. Half of the amount was paid by Russian and international journalists around the world, and the rest was added from Sharogradskaya’s personal savings.

Despite the pressure, RPI continues acting as an independent help desk for journalists, giving the region’s media, bloggers, initiative groups, democratic opposition leaders, and activists an opportunity to raise their voice at press conferences, and advocating for those who are in trouble with the authorities.

Many, including Sharogradskaya, believe that Russian civil society, including the media, faces increasing pressure. NGOs advocating for the freedom of the press must now spend more time and efforts protecting themselves instead of protecting journalists and other parts of the media.

Sharogradskaya says that above everything else, the lack of solidarity among journalists is a major concern. “Our work is to raise this solidarity. This is the only way to withstand the time of repressions.”

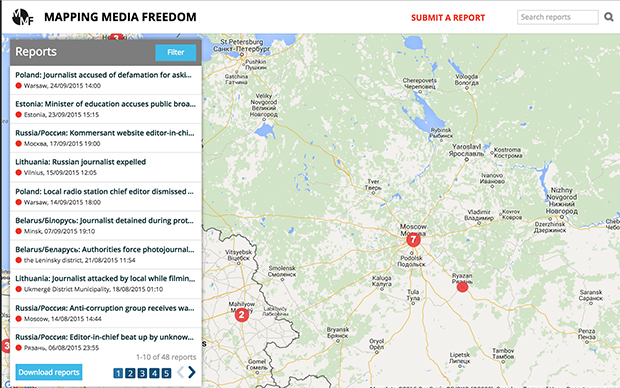

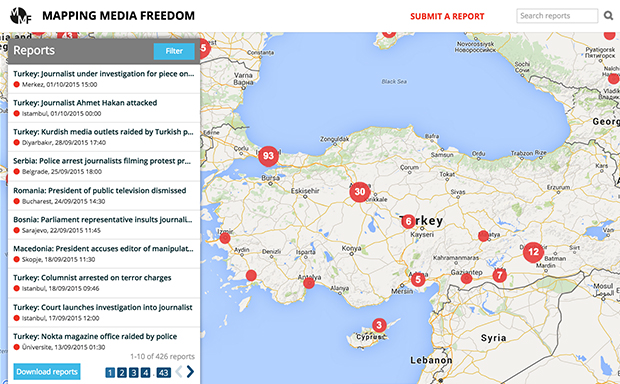

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

08 Oct 15 | Campaigns, Mali, Press Releases

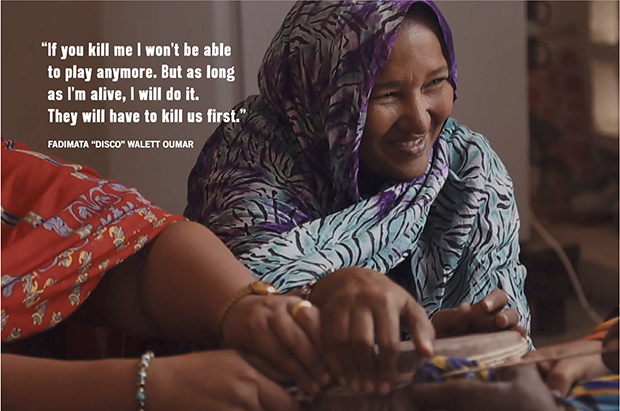

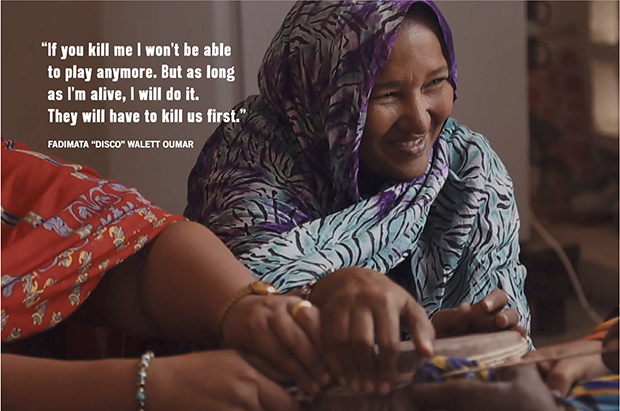

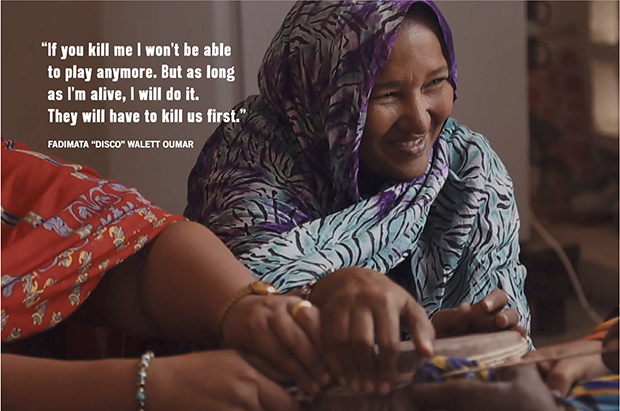

Fadimata “Disco” Walett Oumar, as featured in They Will Have To Kill Us First

Freedom of expression campaigners Index on Censorship and the producers of award-winning documentary They Will Have To Kill Us First are delighted to announce the launch of a new fund to support musicians facing censorship globally.

The Music in Exile Fund will be launched at the European premiere of They Will Have To Kill Us First: Malian Music In Exile – a feature-length documentary that follows musicians in Mali in the wake of a jihadist takeover and subsequent banning of music – at the London Film Festival on 13 October.

In its first year, the Music In Exile Fund will contribute towards Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship, which is a year-long structured assistance programme to support those facing censorship. The funds will be used to support at least one musician or group nominated in the arts category of the awards. This will include attendance at the awards’ fellowship week in April 2016 – an intensive week-long programme to support career development for the artists. This also brings training in advocacy, fundraising, networking and digital security – all crucial for sustaining a career in the arts when under the pressure of censorship. The fellow will also receive continued support during their fellowship year.

Songhoy Blues, who feature in They Will Have To Kill Us First, were nominated for the arts category of the Index Freedom of Expression Awards in 2015. Index’s current arts award fellow is Mouad Belghouat, a Moroccan rapper who releases music as El Haqed. His music publicises widespread poverty and rails against endemic government corruption in Morocco, where he is banned from performing publicly.

Johanna Schwartz, director of They Will Have To Kill Us First, said: “For the two years that followed the ban on music in Mali, I filmed with musicians on the ground, witnessing their struggles and learning what they needed in order to survive as artists. The idea for this fund has grown directly out of those experiences. When faced with censorship, musicians across the world need our support. We are thrilled to be partnering with our long-time collaborators Index on Censorship to launch this fund.”

Our ambition is to widen support as the fund grows to support more musicians in need.

You can donate to the Music In Exile Fund here.

For more details, please contact:

Index on Censorship: Helen Galliano – Helen@indexoncensorship.org

Mojo Musique: Sarah Mosses or Johanna Schwartz – donate@TogetherFilms.org

08 Oct 15 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Turkey

The top of Frederike Geerdink’s blog, Kurdish Matters, still reads: ‘The only foreign journalist based in Diyarbakir’. The Dutch reporter was the only foreign journalist in Turkish Kurdistan until 9 September 2015 when she was deported from the country she lived and worked for nine years.

“There I went in a military convoy, first from Yüksekova to Hakkari, then from Hakkari to Van,” Geerdink wrote a few days later. “As the soldiers were playing loud, rousing nationalist music, I realised that I had turned into a PKK target, being transported on a dark mountainous Kurdistan road in a military vehicle with windows too small to see the starry sky.”

From Van, she’d fly to Istanbul where she’d be forced on a plane back to her The Netherlands. A couple of days earlier she had been arrested while traveling with and reporting on the activities of a group of Kurdish activists who call themselves the Human Shield Group. She was accused of illegally entering a restricted zone and engaging “in an act that helped a terrorist organisation”.

After nine years in Turkey, three of which were in Kurdistan, Geerdink had lost her second home. “I left my heart in Kurdistan,” she posted on Facebook after she’d landed at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport. “I don’t know when, but I will return.”

In the same week when Geerdink was deported, the English version of her book, The Boys are Dead, about the Roboski massacre and the Kurdish question in Turkey, was launched. “A coincidence,” she told Index on Censorship. “I don’t think the Turkish government had planned to help me promote my book.”

A few weeks after her ordeal, she was living a nomadic life in The Netherlands, moving from place to place, staying with friends or family, not really feeling at home anywhere. “I don’t want to be here,” she said. “Don’t get me wrong, everyone is really kind, but I don’t belong here anymore. I want to be there.”

Turkey has one of the world’s worst records on media freedom. Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project has so far recorded 160 reports of violations against journalists in the country since May 2014. Reporters Without Borders has ranked Turkey 154th out of 180 countries on press freedom, and according to Freedom House, Turkey’s status declined from Partly Free to Not Free in 2013.

Reporting on the position of Kurds in Turkey is exceptionally difficult. Prominent journalists have been fired over their coverage of negotiations between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Kurdish and Turkish journalists are often targeted by the police and courts, although it is rare for a foreign journalist to be singled out.

Back in January 2015, Geerdink was arrested by the Turkish authorities for the first time. Her house was searched, she was briefly detained and faced up to five years in prison for ‘terrorist propaganda’. Her detention was condemned worldwide and she was acquitted of the charges in April. Her deportation just a few months later came as a big shock.

Now that even foreign journalists are being targeted, Geerdink said, shows just how bad things are for the position of Kurds in Turkey. “I was the only journalist based there and now there’s one less witness on the ground. And the fewer the witnesses, the more the state has a free hand.”

She added that her treatment should be a warning to others. “They are saying: ‘watch where you go or we’ll kick you out’.” On the other hand, she thinks her deportation brings a lot of negative publicity onto the Turkish government and how they treat journalists, which can be used to put more pressure on the authorities.

In September, two UK-based reporters for VICE were arrested while reporting in Diyarbakir. Although they were released, their Iraqi colleague remains in jail. Seven local journalists are currently detained in the country, many of whom are Kurds. Being a foreigner, Geerdink said the spotlight is on her, but there are many Kurds in prison who nobody knows about, and they deserve the same amount of publicity. “For them it is a matter of life and death.”

Geerdink hopes to return to Turkish Kurdistan as soon as she’s allowed back in. Her lawyers are working hard to appeal the verdict on her deportation. Meanwhile, she is focussing on Syrian Kurdistan, Iraqi Kurdistan and Kurds in Europe.

“I will still be Kurdistan correspondent no matter where I am based.”

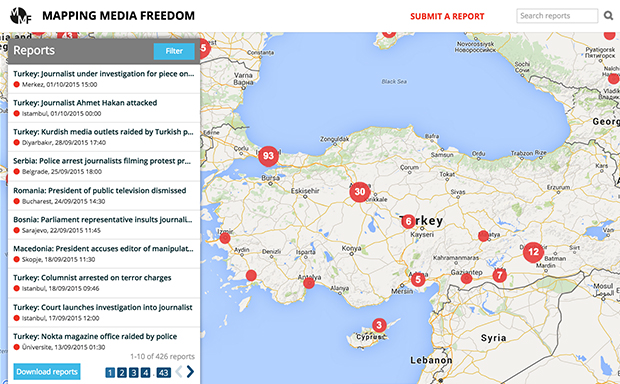

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

08 Oct 15 | About Index, Awards, Mali, mobile, News and features

Index is joining forces with the producers of a new feature-length documentary featuring Mali’s persecuted musicians to launch a fund that will offer support to musicians facing threats, violence, exile and criminal prosecution around the world.

In 2012, Muslim extremist groups captured northern Mali, implemented sharia law and banned all music. Radio stations were destroyed, instruments burned and Mali’s musicians faced torture, even death. They Will Have To Kill Us First: Malian Music In Exile tells the stories of the Malian musicians who fought back and refused to have their music taken away.

The Music In Exile Fund springs directly from witnessing the struggles of musicians featured in the film. The fund will contribute to Index on Censorship’s year-long Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship Programme, supporting at least one nominated musician or group by giving access to bespoke training and assist them to create, perform and share their work in a safe environment.

Songhoy Blues, who feature in They Will Have To Kill Us First, were nominated for the Index Arts award in 2015. The current Arts award fellow is Mouad Belghouat, a Moroccan rapper who releases music as ‘El Haqed’. His music publicises widespread poverty and rails against endemic government corruption in Morocco, where he is banned from performing publicly.

“For the two years that followed the ban on music in Mali, I filmed with musicians on the ground, witnessing their struggles and learning what they needed in order to survive as artists,” said Johanna Schwartz, director of They Will Have To Kill Us First. “The idea for this fund has grown directly out of those experiences. When faced with censorship, musicians across the world need our support. We are thrilled to be partnering with our long-time collaborators Index on Censorship to launch this fund.”

The fund will be launched at the film’s UK premiere at the British Film Institute on October 13.

“When we initiated the Awards Fellowship earlier this year, we wanted to help maximise the impact that our awards could have,” said Jodie Ginsberg, Index on Censorship chief executive. “We hope that this fund will allow us to do even more to assist those facing censorship so that can focus on what they do best: create.”

The funds will be used to support at least one musician or group nominated in the Arts award category. This will include attendance at the Awards Fellowship week in April 2016 – an intensive week-long programme to support career development for the artists. This includes training on advocacy, fundraising, networking and digital security – all crucial for sustaining a career in the arts under the pressure of censorship. The fellow will also receive continued support during their fellowship year.

Our ambition is to widen support as the fund grows to support more musicians in need.

You can donate to the campaign here.

07 Oct 15 | Africa, Angola, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

The resolution calls for the release of all political prisoners and human rights defenders and highlights the case of José Marcos Mavungo, at that time on trial in Cabinda province for the crime of rebellion. Mr. Mavungo was organising a peaceful protest, but the government alleges he was involved with the handling of explosives and leaflets along with other individuals. Despite providing no evidence at trial to connect him with the persons or explosives, and that these men with explosives whom Mr. Mavungo is accused of associating with were not brought to trial, he was convicted and sentenced to six years in prison and to the payment of 50 000 Kwanzas legal fees (approx. US$400) on 14 September. Amnesty International considers him to be a prisoner of conscience.

The resolution further notes the increasing shrinking space for freedoms of expression, assembly and association through arrests, instrumentalisation of the judiciary system to repress dissent by criminally prosecuting individuals for exercising these rights, and the use of violence by security forces to repress peaceful public gatherings. All of these concerns have been documented many times by human rights, civil society and other organisations from within Angola and elsewhere in Africa as well as internationally.

The EP resolution also calls for action from the European Union (EU) and its member states to deliver on their commitments to support and protect human rights defenders worldwide through concrete and visible measures.

In a vote of 550 in favor, with 14 opposed and 60 abstentions, a strong statement regarding these escalations became part of the official parliamentary record.

We, the undersigned national and international organisations, strongly support the resolution by the European Parliament on the Human Rights Situation in Angola. We believe that this resolution underlines the urgent need for action in response to the escalating human rights violations in Angola.

It will be crucial for the EU, its member states and other international actors to provide timely political and material support to Angolan human rights defenders, their lawyers and families and to engage the Angolan authorities on human rights at all levels of relations, including all political, trade and development relations.

We urge the Angolan government to fully implement the measures called for in the resolution including by ending continuing human rights violations, immediately releasing all detained political prisoners, respecting the rights of citizens to enjoy their rights to freedom of expression and assembly, and engaging positively in dialogue with the European Parliament about the very serious human rights issues detailed in the resolution.

The organisations are (in alphabetical order):

Amnesty International

Angola-Roundtable of German Non-Governmental Organizations

Front Line Defenders

Index on Censorship

International Press Institute

International Service for Human Rights

Liberdade Já

OMUNGA

Organização Humanitária Internacional

PEN American Center

Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights

Southern Africa Litigation Centre

Transparência e Integridade, Associação Cívica

Transparency International

World Organisation Against Torture

07 Oct 15 | Malaysia, mobile, News and features

Malaysia’s decision to dismiss a challenge to the colonial-era Sedition Act has limited the country’s freedom of expression.

The Federal Court’s ruling is a setback to persecuted Malaysian cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Haque, aka Zunar, who is facing nine simultaneous charges under the law and will appear court on 6 November.

“The ‘approval’ of the Sedition Act by the Federal Court is totally disappointing, unacceptable and undemocratic,” Zunar said in a statement.

The court, challenged by law professor Azmi Sharom, ruled on 6 October that the Sedition Act 1948 remains constitutional and a valid piece of legislation. Azmi had argued that the Sedition Act 1948 is not a valid law as it was not enacted by parliament and contradicted with the Article 10 of Malaysia’s constitution.

Article 10 of the constitution states, that “(a) every citizen has the right to freedom of speech and expression; (b) all citizens have the right to assemble peaceably and without arms.”

Zunar said: “The decision by the court simply mocked the Constitution and [is] politically motivated.”

The cartoonist said the Sedition Act has been used as political weapon by the government to constrain and curtail freedom of expression since it was introduced in 1948. More than 200 activists – students, lecturers, lawyers, writers, religious activists, opposition leaders and cartoonist – have either been arrested, detained, investigated or charged since last year.

“I am now being slapped with nine charges under the draconian act and facing a possible 43 years of jail term,” he added. “The hope to get justice from the court is just fairy tale.”

Last week, an online sales assistant working for Zunar was told to attend a meeting with police related to the sales of the cartoonist’s books.

07 Oct 15 | About Index, Campaigns, Statements

“We condemn the decision to summons Bahar Moustafa to court. Media reported on October 6 that Mustafa — who once wrote a tweet with the hashtag #KillAllWhiteMen — had received a court summons for malicious communications. Although we do not have the full details for this summons, it is clear that this particular remark by Mustafa posed no direct and imminent danger to anyone – and this is the only test that must be applied when considering limits to free expression. The charges demonstrate once again the problems with this piece of legislation, and others that criminalise free speech, and the way in which these laws are interpreted,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship said.

Mustafa, an employee of the independent students’ union at Goldsmiths, University of London, has been ordered to appear at Bromley Magistrates’ Court on 5 November related to sending a threatening message between 10 November 2014 and 31 May this year, and one of sending a menacing or offensive message via a public network, between the same dates.

07 Oct 15 | Middle East and North Africa, mobile, Morocco, News and features

Index on Censorship Arts award winner 2015: Mouad ‘El Haqed’ Belghouat

Generally speaking, Arabic hip hop comes in two categories. There are rappers in the Gulf who like to brag about how great it is to be really, really rich. Then there are artists in places like Palestine and Algeria who use their work to talk about the endemic problems they face in their communities: disenfranchisement, discrimination, destitution and violence.

Index on Censorship Arts award winner Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat falls under the latter category. Hailing from Morocco, where the youth have been keen consumers of hip hop for many years, El Haqed has had a lot of attention since the Arab Spring. Rapping about poverty, police corruption and oppression in the country, the 24-year old has been felt the full force of the law. Arrested for the first time in 2011, he spent two years in prison before being arrested twice more because of his music.

Index spoke with El Haqed in June when he had just returned to Morocco in high spirits following a tour of Norway, Sweden and Denmark, and was looking forward to performing for the first time in his hometown of Casablanca. Unfortunately, the Moroccan state went to extraordinary lengths — blocking off roads and ordering an electricity company to shut off power — to ensure the concert didn’t go ahead. He is effectively banned from performing live or appearing on TV or radio.

Asked why the Moroccan government wants to silence him so badly, El Haqed said: “Because I continue to speak out against them and fight for freedom of expression.” On several occasions, the authorities have asked El Haqed to renounce his views. “They want me to say that we live in a democracy and that everything is OK, but I have always refused.”

An all too frequent but often unavoidable fact of life as an artist under siege is that there will be times when keeping a low profile seems necessary. While El Haqed is still writing and recording music, he isn’t currently posting to YouTube as he was before. “Publishing music at the minute would only cause more problems,” he explains. He adds, however, that this is only a temporary setback, and publishing on YouTube and to his tens of thousands of social media followers is very much a part of his future plans.

One area of extreme difficulty has been finding the right people — including a producer — to work with. El Haqed used to write music with other artists in Morocco, but this has become an inconvenience. “Musicians were told by the authorities to stop working with me, or they would be made to,” he says.

One area of extreme difficulty has been finding the right people — including a producer — to work with. El Haqed used to write music with other artists in Morocco, but this has become an inconvenience. “Musicians were told by the authorities to stop working with me, or they would be made to,” he says.

Although in the past El Haqed pushed the authorities to give him permission to perform in Morocco, he is resigned to the fact this may never happen. But there is hope. Visa applications pending, he has been invited to spend a week in Florence, Italy, in October for an exchange with Italian musicians, a debate on the music of the new generation and to perform in concert. A major focus of this visit will be to facilitate artistic collaboration.

He has also been invited to perform in Belgium in October by at the 25th anniversary of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights due to his being a “committed musician and human rights defender”.

Like one in five people his age in Morocco, El Haqed doesn’t currently have a job and relies heavily on family and friends for support. While it may be easier if he left Morocco to pursue a career in music, he has no intention of relocating.

“I love my country, and while I want to perform abroad, I will always come back to Morocco,” he says.

Index on Censorship demands Moroccan authorities end their harassment of El Haqed and allow him, and others like him, to perform in the country.

Nominations for the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards are currently open. Act now.

07 Oct 15 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, mobile

Today marks the 200th day of Bahraini prisoner of conscience Dr Abduljalil al-Singace’s protest. Since 21 March, Dr al-Singace has boycotted all solid food in protest of the treatment of inmates at the Central Jau Prison.

We, the undersigned NGOs, call for Dr al-Singace’s immediate and unconditional release, and the release of all political prisoners detained in Bahrain. We voice our solidarity with Dr al-Singace’s continued protest and call on the United Kingdom and all European Union member states, the United States and the United Nations to raise his case, and the cases of all prisoners of conscience, with Bahrain, both publicly and privately.

Dr al-Singace is a former Professor of Engineering at the University of Bahrain, an academic and a blogger. He is a 2007 Draper Hills Fellow at Stanford University’s Center on Democracy Development, and the Rule of Law. He has long campaigned for an end to torture and political reform, writing on these and other subjects on his blog, Al-Faseela. Bahraini Internet Service Providers continue to ban access to the blog and Dr al-Singace has suffered arbitrary detention and torture on multiple occasions. In June 2011, a military court sentenced Dr al-Singace to life imprisonment alongside other prominent protest leaders, collectively known as the ‘Bahrain 13’. He is considered a prisoner of conscience.

Dr al-Singace’s current protest began in response to the violent response of the Ministry of Interior to a riot that took place in the Central Jau Prison on 10 March 2015. Though only a minority of inmates participated in the riot, police collectively punished all detainees, subjecting them to beatings and other humiliating and degrading acts; depriving them of sleep and food; and denying them access to sanitation facilities. Dr al-Singace objects to the humiliating treatment and arbitrary detention to which prison authorities subject him and other prisoners of conscience. Additionally, Dr al-Singace rejects being labelled a criminal, as the government convicted him in 2011 on grounds relating to his peaceful exercise of his freedoms of speech and assembly.

Since Dr al-Singace began his protest, the international community has expressed concerns over the treatment of inmates at Bahrain’s largest prison complex and the condition of Dr al-Singace in particular. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights raised the issue of torture in Bahrain’s prisons in June. In July, the European Parliament passed a resolution on Bahrain calling for the unconditional release of prisoners of conscience, naming Dr al-Singace. The United States clarified its concerns regarding Dr al-Singace in August. The United Kingdom has also expressed its concerns over Bahrain.

In June 2015, NGOs launched a social media campaign for Dr al-Singace – #singacehungerstrike – alongside the University College Union. Since then, NGOs also organised protests outside the Bahrain Embassy, London, and the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office. On 27 August, the 160th day of Dr al-Singace’s protest, 41 NGOs issued an urgent appeal for the release of Dr al-Singace.

For over six months, Dr al-Singace has subsisted on water, fluids and IV injections for sustenance. He is currently interred at the prison clinic. Prison authorities seem to have finally begun to take notice of the international attention his case is attracting, as Dr al-Singace recently received treatment for a nose injury he suffered during his torture in 2011. He had waited over four years to receive such treatment. He also suffered damage to his ear as a result of torture, but has not received adequate medical attention for this injury.

According to Dr al-Singace’s family, the prison authorities will only transfer him to a civilian hospital for treatment if he agrees to wear a prisoner’s uniform, which he refuses to do on the grounds that he is a prisoner of conscience and not a criminal. Since the beginning of his protest, Dr al-Singace has lost 20 kilograms in weight. He is often dizzy and his hair is falling out. He survives on nutritional drinks, oral rehydration salts, glucose, water and an IV drip, and his family states that he is “on the verge of collapse.”

In the prison clinic, Dr al-Singace is not allowed to leave the building and is effectively held in solitary confinement. Though the clinic staff tends to him, he is not allowed to interact with other prison inmates and his visitation times are irregular. Authorities have now lifted an unofficial ban on Dr al-Singace receiving writing and reading materials, but access is still limited: prison staff have now given him a pen, but have still not allowed him access to any paper. The government has also denied Dr al-Singace permission to receive magazines sent to him in an English PEN-led campaign, despite promising to allow him to do so. He has no ready access to television, radio or print media.

We demand Dr Abduljalil al-Singace’s immediate release, and urge the international community to raise his case with Bahrain.

Signatories:

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute of Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

English Pen

European – Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights (EBOHR)

Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR)

Index on Censorship

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Lawyer’s Rights Watch Canada (LRWC)

No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ)

PEN Canada

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Scholars at Risk Network (SAR)

Sentinel Human Rights Defenders

The Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

The European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

The Nonviolent Radical Party Transnational and Transparty (NRPTT)

For more and background information, read the previous statement here.

07 Oct 15 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements, Syria

Syria’s authorities should immediately reveal the whereabouts of Bassel Khartabil, a software developer and defender of freedom of expression, 31 organizations said today. Syrian authorities transferred Khartabil, who has been detained since 2012, from Adra central prison to an undisclosed location on October 3, 2015.

Khartabil managed to inform his family on October 3 that security officers had ordered him to pack but did not reveal his destination. His family has not received any official information but believe based on unconfirmed information they received that he may have been transferred to the military-run field court inside the Military Police base in Qaboun.

“There are real fears that Khartabil has been transferred back to the torture-rife facilities run by Syria’s security forces,” a spokesperson for the groups said. “Khartabil should be on his way out of jail rather than being disappeared again.”

The organizations repeated their call for the immediate release of Khartabil who is facing field court proceedings for his peaceful activities in support of freedom of information.

International law defines a disappearance action by state authorities to deprive a person of their liberty and then refuse to provide information regarding the person’s fate or whereabouts.

Military Intelligence detained Khartabil on March 15, 2012 and he has remained in detention since. He was initially held incommunicado in the Military Intelligence Detention facility in Kafr Souseh for eight months and later in the military jail in Sednaya, where prison personnel tortured him for three weeks, he later told his family. Officials provided Khartabil’s family with no information about where or why he was in custody until December 24, 2012, when authorities moved him to Adra central prison, where Khartabil was eventually allowed visits from his family.

A Syrian of Palestinian parents, Khartabil is a 34-year old computer engineer who worked to build a career in software and web development. Before his arrest, he used his technical expertise to help advance freedom of speech and access to information via the Internet. Among other projects, he founded Creative Commons Syria, a nonprofit organization that enables people to share artistic and other work using free legal tools.

Khartabil has received a number of awards including the 2013 Index on Censorship Digital Freedom Award for using technology to promote an open and free Internet. Foreign Policy magazine named Khartabil one of its Top 100 Global Thinkers of 2012, “for insisting, against all odds, on a peaceful Syrian revolution.”

Military Field courts in Syria are exceptional courts that have secret closed-door proceedings and do not allow for the right to defense. According to accounts of released detainees who appeared before them, the proceedings of these courts were perfunctory, lasting minutes, and in absolute disregard of international standards of minimum fairness. During a field court proceeding on December 9, 2012, a military judge interrogated Khartabil, for a few minutes but he had heard nothing about his legal case since then.

“Bassel has always been a leading advocate for more transparency in Syria and the authorities should immediately reveal his whereabouts and reunite him with his family,” the spokesperson for the groups said.

List of signatories:

- Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture (ACAT)

- Amnesty International

- Arab Foundation for Development and Citizenship

- Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

- Association for Progressive Communications

- Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

- Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

- Euromed Rights (EMHRN)

- FIDH (International Federation for Human Rights), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

- Front Line Defenders

- Global Voices Advox

- Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR)

- Humanist Institute for Cooperation with Developing Countries (HIVOS)

- Human Rights Watch (HRW)

- Index on Censorship

- Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR)

- International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

- Lawyers Rights Watch Canada (LRWC)

- No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ)

- One world foundation for development

- Pax for Peace – Netherland

- Pen International

- RAW in WAR (Reach All Women in WAR)

- Reporters without Borders (RSF)

- Sisters Arab Forum for Human Rights (SAF)

- SKeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedom

- Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR)

- The Day After

- Violations Documentation Center in Syria (VDC)

- Vivarta

- World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders