11 Sep 15 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

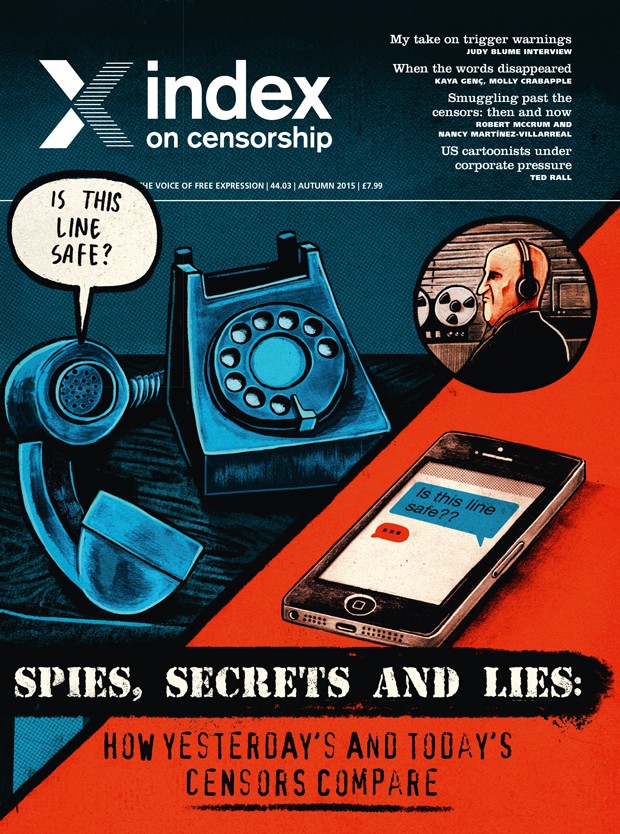

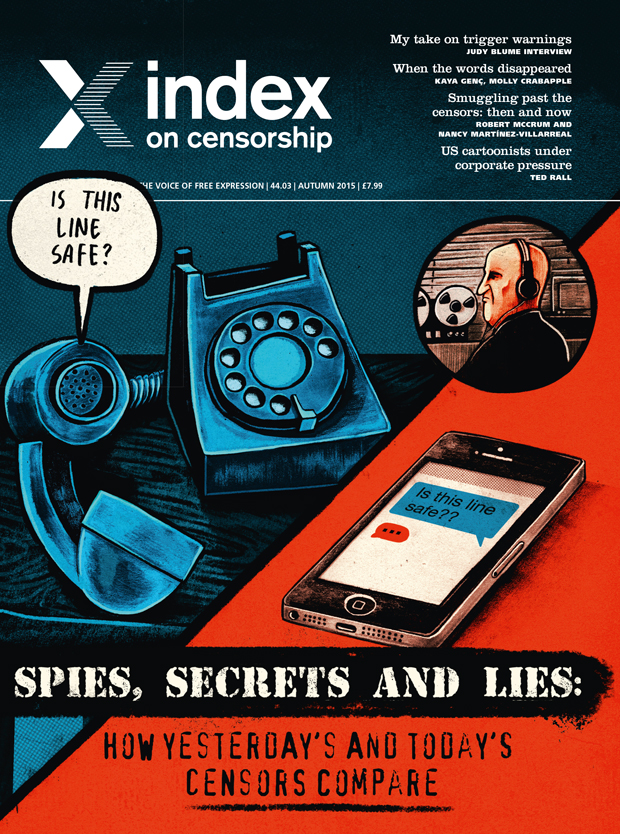

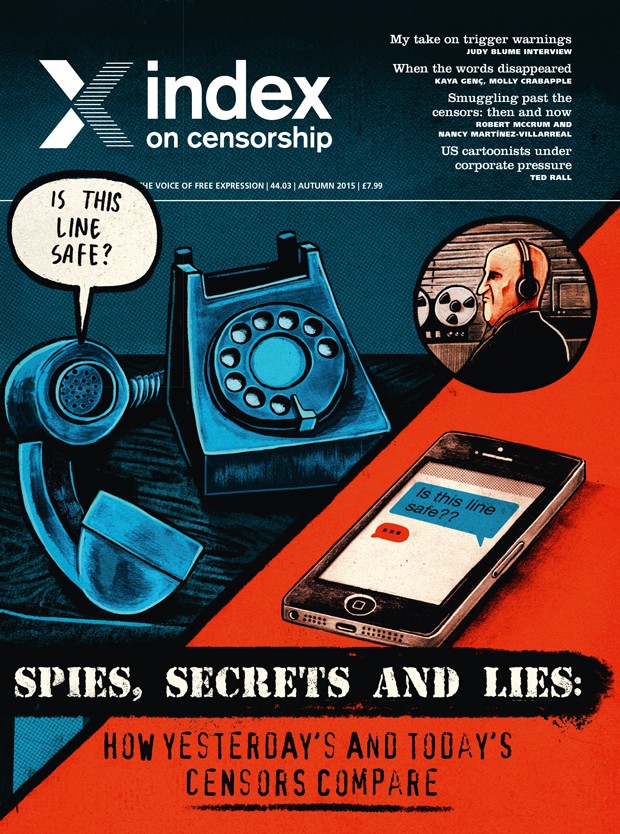

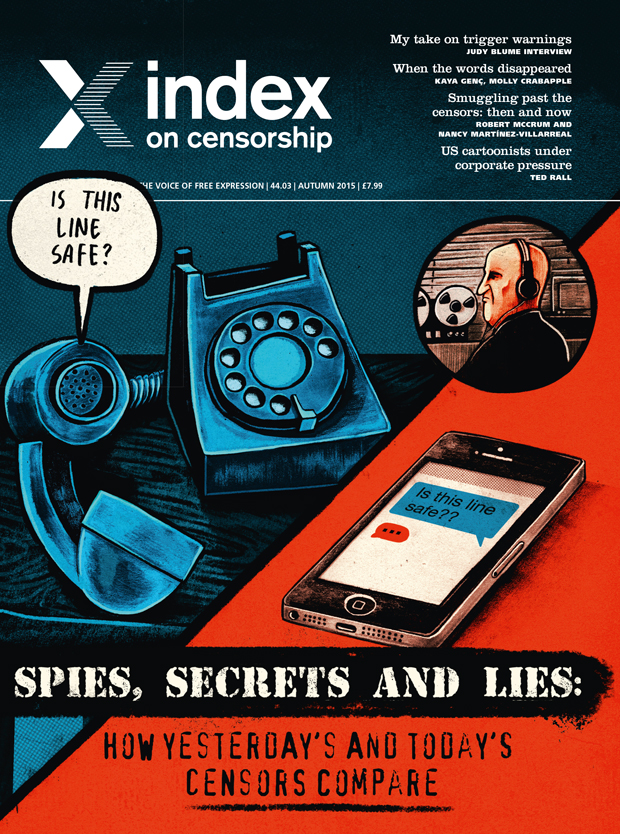

The autumn 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine focuses on comparisons between yesterday’s and today’s censors and will be available from 14 September.

In the latest issue on Index on Censorship magazine Spies, secrets and lies: How yesterday’s and today’s censors compare, we look at nations around the world, from South Korea to Argentina, and discuss if the worst excesses of censorship have passed or whether new techniques and technology make it even more difficult for the public to attain information.

Smuggling documents and writing out of restricted countries has helped get the news out, and into Index on Censorship magazine over the years. In this issue, you can hear three stories of how writing and ideas were smuggled into or out of countries. Robert McCrum swapped bananas for smuggled documents in Communist Czechoslovakia; Nancy Martínez-Villarreal used lipstick containers to hide notes in Pinochet’s Chile and Kim Joon Young tells of how flash drives hidden in car tyres take information into North Korea.

Also in this issue, an interview with Judy Blume on over-protective parents’ stopping children from reading, Molly Crapabble illustrates a new short story from Turkish novelist Kaya Genç, Jamie Bartlett on crypto wars and Iranian satirist Hadi Khorsandi on how writers are muzzled and threatened in Iran. Don’t miss Mark Frary mythbusting the technological tricks that can and can’t protect your privacy from corporations and censors.

There’s also a cartoon strip by award-winning artist Martin Rowson, newly translated Russian poetry and a long extract of a Brazilian play that has never before been translated into English.

CONTENTS: Issue 44, 3

Spies, secrets and lies: How yesterdays and today’s censors compare?

SPECIAL REPORT

New dog, old tricks – Jemimah Steinfeld compares life and censorship in 1980s China with that of today

Smugglers’ tales – Three people who’ve smuggled documents from around the world discuss their experiences

Stripsearch cartoon – Martin Rowson’s regular cartoon is a challenge from Chairman Miaow

From murder to bureaucratic mayhem – Andrew Graham-Yooll assesses what happened to Argentina’s journalists after the country’s dictatorship crumbled

Words of warning – Raymond Joseph, a young reporter during apartheid, compares press freedom in South Africa then and now

South Korea’s smartphone spies– Steven Borowiec reports on a new law in South Korea embedding a surveillance tool on teenagers’ phones

“We lost journalism in Russia” – Andrei Aliaksandrau examines the evolution of censorship in Russia from the Soviet era to today

Indian films on the cutting-room floor – Suhrith Parthasarathy discusses the likes and dislikes of India’s film boards over the decades

The books that nobody reads – Iranian satirist Hadi Khorsandi reports on how it is harder than ever for writers in his homeland to evade censorship

Lessons from McCarthyism – Judith Shapiro looks at the impact of the McCarthyite accusations and fasts forward to address the challenges to free speech in the US today

Doxxed – When prominent women express their views online, they can face misogynist abuse. Video game developer Brianna Wu, who was targeted during the Gamergate scandal, gives her view

Reporting rights? – Milana Knezevic looks at threats to journalism in the former Yugoslavia since the Balkan wars

My life on the blacklist – Uzbek writer Mamadali Makhmudov tells Index how his works continue to be suppressed having already served 14 years on bogus jail charges

Global view – F0r her regular column, Index’s CEO Jodie Ginsberg writes about libraries; how they are vital communities and why censorship should be left at their doors

IN FOCUS

Battle of the bans – US author Judy Blume talks to Index’s deputy editor Vicky Baker about trigger warnings, book bannings and children’s literature today

Drawing down – Ted Rall discusses why US cartoonists are being forced to play it safe to keep their shrinking pay cheques

Under the radar – Jamie Bartlett explores how people keep security agencies in check

Mythbusters – Mark Frary debunks some widely held misconceptions and discusses which devices, programs and apps you can trust

Clearing the air: investigating Weibo censorship in China – Academics Matthew Auer and King-Wa Fu discuss new research that reveals the censorship of microbloggers who spoke out after a documentary on air pollution was shown in China

NGOs: under fire, under surveillance – Natasha Joseph looks at how some of South Africa’s civil rights organisations are fearing for the future

“Some words are more powerful than guns” – Alan Leo interviews Nobel Peace Prize nominee Gene Sharp

Taking back the web – Jason DaPonte takes a look at the technology companies putting free speech first

CULTURE

New world (dis)order – A short story by Kaya Genç about words disappearing from the Turkish language, featuring illustrations by Molly Crabapple

Send in the clowns – A darkly comic play by Miraci Deretti, lost during Brazil’s dictatorship, translated into English for the first time

Poetic portraits – Russian poet Marina Boroditskaya introduces a Lev Ozerov poem, never before published in English, translated by Robert Chandler

Index around the world – Max Goldbart rounds up Index’s work and events in the last three months

A matter of facts – For her regular Endnote column, Vicky Baker looks at the rise of fact-checking organisations being used to combat misinformation

Take out a digital annual magazine subscription (4 issues) from anywhere in the world, £18.

Have four stunning print copies delivered to your doorstep (US and UK), £32.

11 Sep 15 | Campaigns, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Press Releases

Index on Censorship, the European Federation of Journalists and Reporters Without Borders are delighted to announce the expansion and redesign of Mapping Media Freedom, which records threats to journalists across Europe, and which will now also cover Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

First launched in May 2014, the map documents media freedom violations throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries including the Balkans and Turkey.

More than 700 reports were logged on the map in its first year, lifting the lid on the everyday threats to media freedom that have previously gone largely unreported or undocumented.

“Mapping Media Freedom has highlighted the kinds of threats faced by media organisations and their staff everyday throughout Europe — from low-level intimidation to threats of violence, imprisonment, and even murder. Having a detailed database of these incidents – most of which previously went unreported — helps us and others to take action against the culprits,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

The relaunched online platform will make it easier for policy makers and activists to identify trends in media freedom and to respond efficiently with immediate assistance or to campaign on specific issues. It also provides support such as legal advice and digital security training to journalists at risk. Anyone can submit their own reports to the site for verification by project officers.

“At a time when freedom of information is facing threats not seen since the times of the Soviet Union, supporting journalists and bloggers is crucial. While part of the continent is sinking in an authoritarian drift, online surveillance has become a common challenge”, said RSF Programme Director Lucie Morillon.

Following renewed funding from the European Commission earlier this year, the crowd-sourced map incorporates new features including country filters and an improved search facility. The project also aims to forge new alliances among journalists across the continent, especially young media practitioners who will find useful resources and in depth coverage on a dedicated “Free Our Media!” page.

In reaction to new draconian measures and violence in the region, the new design coincides with an expansion into Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. All new reports from this area will be available in English and the regional language.

“The enlargement of the monitoring process to Ukraine, Russia and Belarus is good news for journalists and media workers in the region. Journalists are usually at the heart of violent demonstrations, clashes and armed conflicts where they may be shot, assaulted, kidnapped, arrested, abused and killed. They are facing difficult professional challenges between extremists or propaganda agents. Thanks to its affiliates, the EFJ will continue to document all media violations and raise awareness to end impunity when violations occur”, said Mogens Blicher Bjerregård, EFJ President.

Partners, country correspondents and affiliates to the project — including Human Rights House Ukraine, Media Legal Defence Initiative and European Youth Press — will work together to ensure the growing threats to media freedom in the region are highlighted, and tackled.

For further information please contact Hannah Machlin, project officer,hannah@indexoncensorship.org, +44 (0)207 260 2671

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

10 Sep 15 | mobile, News and features, South Africa

Back in the days when the ruling National Party and their thought police ruled South Africa with an iron fist, one of the most powerful bodies tasked with enforcing Apartheid’s staunch Calvinistic values was the Film and Publications Board (FPB). A group of conservative, mainly Afrikaans men and women, it was their job to scrutinise and censor publications: books, movies and music.

Anything depicting even a hint of a mixing of races resulted in either an outright ban or, in the case of movies, ordered to make jarring cuts that often edited out key parts of the story. Suggestions of sex – between people of different colours – was verboten. Anything of a perceived political nature that didn’t fit in with ruling party’s narrow views was instantly banned.

The power to ban publications lay with the minister of the interior under the Publications and Entertainments Act of 1963. An entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica explains its purpose: “Under the act a publication could be banned if it was found to be ‘undesirable’ for any of many reasons, including obscenity, moral harmfulness, blasphemy, causing harm to relations between sections of the population, or being prejudicial to the safety, general.”

The result was that literally thousands of books, newspapers and other publications and movies were banned in South Africa – and possession of them was a criminal offence.

It led to some truly bizarre rulings, like the banning of Anna Sewell’s classic book Black Beauty because the censors, who clearly didn’t bother to read it, thought it was about a black woman.

I still have clear memories of returning from visits to multiracial Swaziland with banned publications hidden under carpets, slipped behind the dashboard or under spare wheels. That was how I got hold of a copy of murdered Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko’s I Write What Like and exiled South African editor Donald Woods’ Cry Freedom, about the life and death of Biko.

I still remember clearly how my heart skipped a beat when border guards checking through my car got uncomfortably close to uncovering my contraband literature. It was a huge risk because, had it been discovered, it would have meant prosecution and a criminal record for possession of banned literature.

Even having a copy of Playboy was a criminal offence and more than one South African found himself with a criminal record after a copy of the magazine was found stashed in his luggage on his return to South Africa from an overseas trip.

But when South Africa’s new, post-Apartheid constitution came into effect in 1996, it brought new freedoms for South Africans: books and movies banned by the Apartheid government were unbanned. Sex also came out into the open and, for those so inclined, pornography became freely available in the ubiquitous sex shops that opened their doors on high streets and side streets all over the country.

Then, the world wide web was in its infancy in South Africa, available only to the academics and privileged few who could afford it. But now, almost two decades later in a move that has raised fears of a new wave of censorship, the South African government last month approved a bill that has been widely criticised for seeking to curb internet freedoms. Informed by a draft policy drawn up by the FPB it seeks to amend the Film and Publications Act of 1996 – which had itself, replaced the Apartheid-era version of the Act – by adapting it for 21st century technological advances.

The amendments “provide for technological advances, especially online and social-media platforms, in order to protect children from being exposed to disturbing and harmful media content in all platforms (physical and online)”, according to a recent cabinet statement.

“The bill strengthens the duties imposed on mobile networks and internet service providers to protect the public and children during usage of their services,” it said, adding that the regulatory authority would not “issue licences or renewals without confirmation from the Film and Publication Board of full compliance with its legislation.”

The draft policy covers several areas including preventing children from viewing pornography online, hate speech and racist content.

But it also led to fear that it could be used to impose pre-publication censorship. These fears were allayed to some extent when a compromise was reached exempting content published by media registered with the Press Council of South Africa, which recently revised its press code to include regulation of online content exempted from the bill. But this is cold comfort for media who are not members, leaving them and bloggers, social media commentators and ordinary citizens vulnerable.

As it now stands anyone uploading content to the internet or posting content to social media would need to register with the FPB and submit their content before publishing anything. The proposed changes to the law would severely limit South Africa’s hard-earned, constitutional right to free speech, warn critics, who believe it would not pass constitutional muster.

This is reinforced by a legal opinion prepared for the Right to Know Campaign (R2K), which believes that the proposed bill is unconstitutional in several areas and also “unjustifiably limits the right to freedom of expression”. Opponents have made it clear that if it passes into law they will take it to the Constitutional Court.

There is no doubt that the battle lines have been drawn. Already 32,000 people opposing the bill have signed an Avaaz petition, while another 9,000 people have signed an R2K petition.

But the real issue is whether the FPB would be able to enforce it and whether trying to police the internet is just as bizarre as their predecessor’s banning of Black Beauty.

This column was posted on 10 Septemeber 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

09 Sep 15 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

Post-Soviet Union, after the fall of the Berlin wall, after the Bosnian war of the 1990s, and after South Africa’s apartheid, the world’s mood was positive. Censorship was out, and freedom was in.

But in the world of the new censors, governments continue to try to keep their critics in check, applying pressure in all its varied forms. Threatening, cajoling and propaganda are on one side of the corridor, while spying and censorship are on the other side at the Ministry of Silence. Old tactics, new techniques.

While advances in technology – the arrival and growth of email, the wider spread of the web, and access to computers – have aided individuals trying to avoid censorship, they have also offered more power to the authorities.

There are some clear examples to suggest that governments are making sure technology is on their side. The Chinese government has just introduced a new national security law to aid closer control of internet use. Virtual private networks have been used by citizens for years as tunnels through the Chinese government’s Great Firewall for years. So it is no wonder that China wanted to close them down, to keep information under control. In the last few months more people in China are finding their VPN is not working.

Meanwhile in South Korea, new legislation means telecommunication companies are forced to put software inside teenagers’ mobile phones to monitor and restrict their access to the internet.

Both these examples suggest that technological advances are giving all the winning censorship cards to the overlords.

But it is not as clear cut as that. People continually find new ways of tunnelling through firewalls, and getting messages out and in. As new apps are designed, other opportunities arise. For example, Telegram is an app, that allows the user to put a timer on each message, after which it detonates and disappears. New auto-encrypted email services, such as Mailpile, look set to take off. Now geeks among you may argue that they’ll be a record somewhere, but each advance is a way of making it more difficult to be intercepted. With more than six billion people now using mobile phones around the world, it should be easier than ever before to get the word out in some form, in some way.

When Writers and Scholars International, the parent group to Index, was formed in 1972, its founding committee wrote that it was paradoxical that “attempts to nullify the artist’s vision and to thwart the communication of ideas, appear to increase proportionally with the improvement in the media of communication”.

And so it continues.

When we cast our eyes back to the Soviet Union, when suppression of freedom was part of government normality, we see how it drove its vicious idealism through using subversion acts, sedition acts, and allegations of anti-patriotism, backed up with imprisonment, hard labour, internal deportation and enforced poverty. One of those thousands who suffered was the satirical writer Mikhail Zoshchenko, who was a Russian WWI hero who was later denounced in the Zhdanov decree of 1946. This condemned all artists whose work didn’t slavishly follow government lines. We publish a poetic tribute to Zoshchenko written by Lev Ozerov in this issue. The poem echoes some of the issues faced by writers in Russia today.

And so to Azerbaijan in 2015, a member of the Council of Europe (a body described by one of its founders as “the conscience of Europe”), where writers, artists, thinkers and campaigners are being imprisoned for having the temerity to advocate more freedom, or to articulate ideas that are different from those of their government. And where does Russia sit now? Journalists Helen Womack and Andrei Aliaksandrau write in this issue of new propaganda techniques and their fears that society no longer wants “true” journalism.

Plus ça change

When you compare one period with another, you find it is not as simple as it was bad then, or it is worse now. Methods are different, but the intention is the same. Both old censors and new censors operate in the hope that they can bring more silence. In Soviet times there was a bureau that gave newspapers a stamp of approval. Now in Russia journalists report that self-censorship is one of the greatest threats to the free flow of ideas and information. Others say the public’s appetite for investigative journalism that challenges the authorities has disappeared. Meanwhile Vladimir Putin’s government has introduced bills banning “propaganda” of homosexuality and promoting “extremism” or “harm to children”, which can be applied far and wide to censor articles or art that the government doesn’t like. So far, so familiar.

Censorship and threats to freedom of expression still come in many forms as they did in 1972. Murder and physical violence, as with the killings of bloggers in Bangladesh, tries to frighten other writers, scholars, artists and thinkers into silence, or exile. Imprisonment (for example, the six year and three month sentence of democracy campaigner Rasul Jafarov in Azerbaijan) attempts to enforces silence too. Instilling fear by breaking into individuals’ computers and tracking their movement (as one African writer reports to Index) leaves a frightening signal that the government knows what you do and who you speak with.

Also in this issue, veteran journalist Andrew Graham-Yool looks back at Argentina’s dictatorship of four decades ago, he argues that vicious attacks on journalists’ reputations are becoming more widespread and he identifies numerous threats on the horizon, from corporate control of journalistic stories to the power of the president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, to identify journalists as enemies of the state.

Old censors and new censors have more in common than might divide them. Their intentions are the same, they just choose different weapons. Comparisons should make it clear, it remains ever vital to be vigilant for attacks on free expression, because they come from all angles.

Despite this, there is hope. In this issue of the magazine Jamie Bartlett writes of his optimism that when governments push their powers too far, the public pushes back hard, and gains ground once more. Another of our writers Jason DaPonte identifies innovators whose aim is to improve freedom of expression, bringing open-access software and encryption tools to the global public.

Don’t miss our excellent new creative writing, published for the first time in English, including Russian poetry, an extract of a Brazilian play, and a short story from Turkey.

As always the magazine brings you brilliant new writers and writing from around the world. Read on.

© Rachael Jolley

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.

08 Sep 15 | Academic Freedom, Magazine, mobile, Student Reading Lists

Today, technology is being used frequently as a censorship tool as well as a way of getting around censorship. The technology and censorship reading list combines a number of articles released over a twenty-year period on the interference technology can have on free expression and the technological advances meaning censors are being more easily evaded. Includes Bibi van der Zee on the impact of Twitter in driving global political change.

Students and academics can browse the Index magazine archive in thousands of university libraries via Sage Journals.

Technology and censorship articles

Time travel to the web of the past and future: Internet predictions revisited, two decades on by Mike Godwin

Mike Godwin, December 2014; vol. 43, 4: pp. 106-109

Twenty years on, Mike Godwin revisits his article on the arrival of the online world and assesses what he got right, and what challenges remain today

Technology Bytes Back: Censorship and the new communication order by Nan Levinson

Nan Levinson, February 1993; vol. 22, 2: pp. 4

In the early days of the internet, Nan Levinson discusses new technologies and their use in the fight against censorship

Cyber Wars by Ron Deibert and Rafal Rohozinski

Ron Deibert and Rafal Rohizinski, March 2010; vol. 39, 1: pp. 79-90

A look at the battle for online space

Virtually Free by Brian Winston and Paul Walton

Brian Winston and Paul Walton, January 1996; vol. 25, 1: pp. 78-83

One director and one fellow from Cardiff University’s school of journalism discuss the suppression of new technology

Global View: the power of noise in the fight against censorship by Jodie Ginsberg

Jodie Ginsberg, December 2014; vol. 43, 4: pp. 51-52

In her quarterly column, Index on Censorship’s chief executive looks at people power and the power of noise

Twitter Triumphs by Bibi van der Zee

Bibi van der Zee, November 2009; vol. 38, 4: pp. 97-102

Journalist and author Bibi van der Zee assesses the impact of Twitter on political change

Future Web: The N-Generation by Don Tapscott

Don Tapscott, November 2007; vol. 36, 4: pp. 51

Don Tapscott looks optimistically at the web’s potential for opening up global information-sharing

Going Mobile by Danica Radovanovic

Danica Radovanovic, December 2012; vol. 41, 4: pp 112-116

Danica Radovanovic on the new role phones are playing in spreading news and information

The reading list for technology and censorship can be found here

08 Sep 15 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Index on Censorship welcomes the latest statement from the National Youth Theatre (NYT) clarifying why it cancelled the production of Homegrown, a play which explored Islamic radicalisation among young people in the United Kingdom.

The production was two weeks into rehearsals when the cancellation was announced. The show, which had been in development for six months, was the product of workshops with British young people aged between 16 and 25. The production team and some of the cast released separate statements in response to the latest comments from the National Theatre.

Index remains deeply concerned that an arts project exploring an important subject, which young people of all ethnicities need to be able to discuss and debate, was closed down.

“We are worried that, without even a line of legislation being debated, the government has created an atmosphere whereby arts organisations are increasingly nervous of putting on any play that touches controversial subjects, and specifically the question of Islamic extremism,” said Index on Censorship chief executive Jodie Ginsberg.

“We recognise that arts organisations have a duty to protect staff and audiences, but worry that a fear of offence is preventing them from fulfilling their duties to protect free expression. Arts groups need more support from the authorities – such as local police and councils – to ensure controversial work can be staged.”

Art and the Law: Guides to the legal framework and its impact on artistic freedom of expression

|

Child Protection: PDF | web

Counter Terrorism: PDF | web

Public Order: PDF | web

Obscene Publications (available autumn 2015)

Race and Religion (available autumn 2015)

Art and the Law main page for access to the guides, case studies and resources.

|

08 Sep 15 | United Kingdom

The National Youth Theatre’s decision to commission Homegrown was born out of a proven track record of commissioning and producing work with young people, some as young as 14, that tackles challenging subjects and pushes artistic boundaries.

Our unique commitment as an organisation is to the creative and personal development of young people through theatre. That stated aim is what differentiates us and informs the work we do and the decisions made by our executive body. The NYT has never shied away from tackling controversial subjects. If this play was to provide those opportunities for the cast, we required the potentially controversial subject matter to be handled sensitively and with editorial balance and justification.

The decision to commission Homegrown was taken in view of those commitments and aims, and the decision to cancel it was taken according to the same criteria.

Despite a lengthy and willingly collaborative process, the co-creators were not able to reassure us that the content of Homegrown satisfied these understandable and important criteria. Our position was further compromised by the creative team’s inability to deliver a completed script at any time, therefore we could have no certainty that the play would either be ready for the planned opening night, or that if completed it would meet our aims and responsibilities as a youth arts charity. Complaints and concerns expressed by members of the production team, the cast and parents compounded the issue and rendered our position completely untenable.

Clearly our commitment to our members goes beyond an editorial one, and their safety and wellbeing is of paramount importance at all times. The subject matter of this play, its immersive form and its staging in a school required us to go beyond even our usual stringent safeguarding procedures to ensure the security of the venue and safety of cast members. However, we can categorically state that no external parties had any involvement in the decision to cancel the public presentation of Homegrown. It was a decision taken solely by the executive of the NYT and one that we sadly felt compelled to make.

We had hoped to address these differences out of the public gaze and directly with the creative team. However, we recognise the wider interest that the decision to cancel the production has attracted, and with the release of information today from the Arts Council it is only appropriate that we address this publicly and fully.

We do not regret commissioning Homegrown and wholeheartedly agree with those that have stated that the issues raised by the creeping radicalisation of the young should be addressed by the arts. We set out to do so but on this occasion were not successful.

We acknowledge that our view of the readiness of the play as an NYT production does not chime with that of the creative team. However we can only base our decisions on the facts, and on the unique criteria upon which the NYT is proudly founded.

We are releasing the rights in Homegrown to Omar El-Khairy and wish him and Nadia Latif well in securing another outlet for their show, when it is completed.

— Paul Roseby, artistic director of the National Youth Theatre

08 Sep 15 | United Kingdom

This statement is in response to an email sent by Paul Roseby, Artistic Director of The National Youth Theatre (NYT) to The Arts Council of England (ACE), in which our play, Homegrown, and its creative team were labelled as “extremist”. The creative team did not have an “extremist agenda”, they had one of support and allowance to a cast of over 100 artists who developed a response to pressing issues such as radicalisation.

We want to clarify that as a company working on this production we have the utmost respect and adoration for work that NYT do. The many members of NYT are not only our friends and colleagues, but they are also the people that will ultimately inspire the world as artists. We will continue to be staunch defenders of NYT and will work hard to be as involved as possible, because no other outlet for youthful creativity exists on the same playing field.

On the 31st July, Paul Roseby came before us as a company and explained that Homegrown was being cancelled. The afternoon before, Roseby and other significant figures within the organisation came to see Act 2, which is just a single act in a five-act play; and purposely the most controversial section of the play. As Roseby never viewed previous devised sections of the production we believe he was unaware of the play’s structure. This structure was carefully orchestrated in order to challenge every prospective audience member on a personal level, asking them to reassess their current views and received-opinions, whatever they may be. The message we are presenting with Homegrown is a well-rounded and intelligent discussion of a matter that needs to be dealt with in a direct and unmediated manner.

Claims were made within a statement by NYT that their position to continue forward with the play was “further compromised by the creative team’s inability to deliver a completed script at any time”. This is thoroughly incorrect as several attempts were offered by the creative team and the script was able to be read at any given time. Within the email that was sent to ACE they called for an overall “intelligent character arc,” as if dismissing the majority of individual, shorter character nuance already depicted within the piece. There is no overall intelligent arc on the issue of radicalisation. It is a difficult and multi-faceted discussion, which Homegrown looks to explore in as much of its entirety as possible.

With the inevitably delicate nature of coming into a creative process with such controversial topics, we sometimes felt like we treaded a fine line as a company. However, the overwhelming support from the entire creative team, specifically Nadia and Omar, assured us that we always had a heightened level of trust and safety. Every day as we peeled back yet more layers of the complex and nebulous issues surrounding radicalisation and Islamophobia, we became more aware of what was happening in the world around us. Our views were always treated with the utmost care and we were always given the option to refrain from participating in aspects we might initially feel uncomfortable with.

The issue of censorship undermines the very nature of art and, in this instance, has become an undeniable signpost of the state of our nation as one still rife with phobia. It is a genuine worry on behalf of the freedom of speech promised to creatives in this country and we do feel silenced as artists. The irony being that this is one of the poignant elements which runs through our play, Homegrown.

Signed by the following members of the Homegrown cast:

Charlotte Elvin

Shakeel Haakim

Gemima Hull

Daisy Fairclough

Megan Foran

Noah Burdett

Patrick Riley

Matthew Rawcliffe

Karim Benotmane

Saul Barrett

Rhys Stephenson

Grace Cooper Milton

Daniel Rainford

Anshula Mauree-Bain

Donna Banya

Aled Williams

Joshua Levy

Vanessa Dos Santos

Yohanna Ephrem

Amara Okereke

Cayvan Coates

Molly Rolfe

Yemurai Zvaraya

Qasim Mahmood

Sam Rees Baylis

Corey Mylchreest

Sam Johnson

Charlie O’Conor

Mohammed B. Mansaray

Zion Washington

Ellis Bloom

Mani Sidhu

Chance Perdomo

Michelle Jamieson

Anna Chedham-Cooper

Kai Kwasi Thorne

Julia Masli

08 Sep 15 | United Kingdom

At the beginning of this year the National Youth Theatre approached us with an idea for a show – to create a large-scale, site-specific, immersive piece looking a the radicalisation of young British Muslims. The original commission was intended to use the Trojan Horse affair as its lens, although very early in our process that angle was abandoned in favour of something more nuanced. Homegrown was intended to be an exploration of radicalisation, the stories behind the headlines and the perceptions and realities of Islam and Muslim communities in Britain today. It’s important to state, however, that we had a number of reservations about making a play about ‘British Muslims going to join ISIS’. Throughout our careers, we have resisted playing to the logic of the entertainment industries and their particularly crude game of identity politics. Homegrown wasn’t to be FUBU – For Us By Us. We weren’t force-feeding our views to mindless young people, but exposing an astute and thoughtful young cast to the full spectrum of voices who are currently having that very conversation about radicalisation. We were giving them certain tools – a language, really – and then allowing them to work their way through it all. Over six months of assembling our enormous cast and workshopping ideas, we were very clear about exactly what we were making, and that the drive behind this was to create a piece of theatre which unsettled all the preconceived ideas people would come with to this subject matter.

Given our assumed closeness to the material, many would have expected us to have some kind of insider perspective to the constant barrage of questions and curiosities in today’s relentless conversation around Islam and it perceived modern day hang ups. We’re told to give serious attention to culture. It’s now said that culture is a matter of life and death – where being able to tell apart the Good Muslim and the Bad Muslim has become a central tenant of this warped, militarised worldview. Homegrown had no answers or solutions, no agenda or mission statement. It didn’t seek to educate, repair or improve people – but something in you would have shifted, we hope. If anything, we wanted to turn this kind of culture talk on its head.

Trouble was first encountered when the day after announcing the show to the press, our original venue of Raine’s Academy in Bethnal Green withdrew, after pressure from Tower Hamlets council. We were asked to be silent on the council’s pressure, so that a new venue could be secured with no problem – the official party line would be “logistical issues”. The show then had to be signed off by Camden Council in order to secure us our eventual venue of UCL Academy. We went into rehearsals with 70% of the show scripted (and signed off by NYT), and the remaining 30% to be devised with the cast during rehearsals. In a production meeting in the first week we were told that a meeting between the NYT and the police had taken place. We do not know who instigated that meeting, as we were not made aware of it until it had happened. The police wanted to read the final script, attend the first three shows, plant plain clothes policemen in the audience and sweep with the bomb squad. When we protested these measures, we were told the police held no power of ultimatum, and the issue was never raised again.

Rehearsals were brilliant, on schedule, and exceeded all our expectations. We were filled with nothing but admiration and deep respect for our amazing brave cast – who were really taking the material and running with it. We were then exactly halfway through rehearsals when we received an email late at night from NYT to tell us that Homegrown was cancelled. We would have done our first full run of the show two days after that. There was no warning, no consultation and no explanation. All our attempts at meetings with the NYT since then have been delayed and then cancelled.

In terms of the current discussions around censorship and artistic freedoms, it’s important to us to clarify that the cancellation of Homegrown doesn’t fall into the same categories as Bezhti, Exhibit B or The City. The tendency to conflate all these cases does a disservice to the nuances of each – and in some instances banalises the legitimate anger they have created. There’s qualitative differences between a show pulled due to pressure exerted by particular groups or communities and Homegrown, which came under the watchful gaze of both formal institutions and arms of the state. There’s no question that had the show been cancelled due to Muslim rage, then we would be celebrated as contemporary Salman Rushdies – courageous bastions of free speech fighting off conservative or reactionary forces within our imagined communities rather than as either incompetent artists or unrefined agitators. We jump to support artists struggling to make work in the regimes of the East, but here in our haven of Western liberal democracy, we hesitate to stand behind those pushing against some of that very same, more insidious, authoritarianism. We’re all making art in a particular political climate – which includes Prevent and Channel. These are programmes which, although intended to stop people getting drawn towards violent extremism, are creating an environment in which certain forms of questioning of the given narrative pertaining to radicalisation or extremism can be closed down. If the acceptable parameters of this discussion are to remain that of inarticulate, mad mullahs in one corner, self-hating Ayaan Hirsi Alis in the other, all refereed by think tank dwellers such as Maajid Nawaaz – then this vital conversation will continue to go nowhere.

Signed, Nadia Latif (director and co-creator), Omar El-Khairy (writer and co-creator)

07 Sep 15 | Campaigns, mobile, Turkey

Prosecutors filed a case against Today’s Zaman columnist Yavuz Baydar on Saturday for “insulting” the president in two recent columns.

“This is the latest in a number of cases of journalists being targeted and charged for insulting the president, which in turn forms part of a wider crackdown on a free and independent media in Turkey,” said Index chief executive Jodie Ginsberg.

“The international community needs to do more to halt this rapidly deteriorating situation.”

Last week Turkey freed two British journalists working for Vice, an online news organisation, who had been charged with “aiding a terrorist organisation”, but their colleague Mohammed Ismael Rasool remains in jail.

“We, those trying to perform their jobs in the media, are using our rights to provide information and criticise the government based on rights granted to us by the Constitution, the laws and international treaties we are a party of,” Baydar said in an interview, published on BGNNews.com. “Being critical, questioning and warning is our professional responsibility. We shall continue to criticise. Just like many other colleagues who are investigated [on the same charge], there is no intention to insult in these columns but the right to criticise was used. I am saddened. I am concerned for our country and the media.”

In July it was announced that Baydar was being awarded Italy’s prestigious Caravella Meditterraneo/Mare Nostrum prize for his work on press freedom and media independence in Turkey.

07 Sep 15 | Magazine, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

07 Sep 15 | Magazine, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

[vc_row disable_element=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1495011859122{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column css=”.vc_custom_1474781640064{margin: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477669802842{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;}”]CONTRIBUTORS[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1495011867203{margin-top: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781919494{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Karim Miské” title=”Novelist” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89017″]Karim Miské is a documentary maker and novelist who lives in Paris. His debut novel is Arab Jazz, which won Grand Prix de Littérature Policière in 2015, a prestigious award for crime fiction in French, and the Prix du Goéland Masqué. He previously directed a three-part historical series for Al-Jazeera entitled Muslims of France. He tweets @karimmiske[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781952845{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Roger Law” title=”Caricaturist ” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89217″]Roger Law is a caricaturist from the UK, who is most famous for creating the hit TV show Spitting Image, which ran from 1984 until 1996. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Observer, The Sunday Times and Der Spiegel. Photo credit: Steve Pyke[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781958364{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Canan Coşkun” title=”Journalist” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”89018″]Canan Coşkun is a legal reporter at Cumhuriyet, one of the main national newspapers in Turkey, which has been repeatedly raided by police and attacked by opponents. She currently faces more than 23 years in prison, charged with defaming Turkishness, the Republic of Turkey and the state’s bodies and institutions in her articles.[/staff][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”top” css=”.vc_custom_1474815243644{margin-top: 30px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 30px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1474619182234{background-color: #455560 !important;}”][vc_column_text el_class=”text_white”]Editorial

In the world of the new censors, governments continue to try to keep their critics in check, applying pressure in all its varied forms. Threatening, cajoling and propaganda are on one side of the corridor, while spying and censorship are on the other side at the Ministry of Silence. Old tactics, new techniques.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720631074{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495012422692{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ben-jennings-autumn2015-cover-2.jpg?id=69604) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner css=”.vc_custom_1474716958003{margin: 0px !important;border-width: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495012396487{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Contents

A look at what’s inside the autumn 2015 issue[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720637924{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495012543978{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/magazine-spies-frontline-sp.jpg?id=70437) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner css=”.vc_custom_1474716958003{margin: 0px !important;border-width: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495013266065{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Magazine Launch Event

Who are modern technological advances really empowering?[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1491994247427{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493814833226{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495012849211{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/bosnia-jan22015.jpg?id=62738) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495012904051{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Reporting rights?

In a series of interviews with journalists in the former Yugoslavia, Milana Knezevic reports on the new elites in control, death threats, and the legacy of the post-war period of the early 2000s.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493815095611{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495012978309{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/judy-blume-creditElenaSeibert-620.jpg?id=69405) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495013035840{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Magazine Extra: Interview

US author Judy Blume talks to Vicky Baker about parents’ and teachers’ overly protective attitudes to young people’s feelings, and how she has spent the last 45 years tackling bans and censorship.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1493815155369{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1495013212207{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/kirchner.jpg?id=46296) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner 0=””][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1495013160893{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]After Argentina’s dictatorship

Former editor of Index on Censorship Andrew Graham-Yooll assess what happened after the regime crumbled, and looks at the new means of controlling the message.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”90659″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://shop.exacteditions.com/gb/index-on-censorship”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine on your Apple, Android or desktop device for just £17.99 a year. You’ll get access to the latest thought-provoking and award-winning issues of the magazine PLUS ten years of archived issues, including Spies, secrets and lies.

Subscribe now.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.