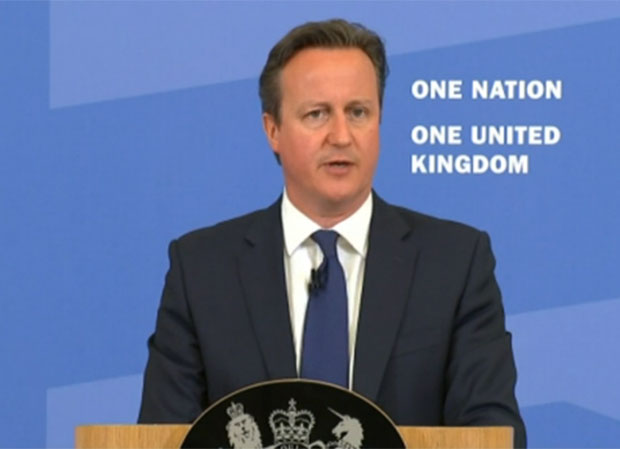

21 Jul 15 | Art and the Law Case Studies, Artistic Freedom Case Studies

Installation image from Xenofon Kavvadias: The law is no less conceptual than fine art at 10 Vyner Street. With permission of the artist.

“The law is no less conceptual than fine art”

Exhibition of Illegal Books by Xenofon Kavvadias

10 Vyner Street London E8

5th May – 17th June 2011

Description of the work

In this show books that are or can be considered illegal under contemporary UK anti-terrorist legislation were displayed as an art installation. The books represented the full spectrum of ideologies and beliefs that can be considered illegal in the UK.

The books were uniformly hard-bound without titles, accompanied by text describing the content and context in which it was published. Background information, correspondence and records of interviews were displayed in the gallery.

The gallery was well lit and the viewer was encouraged to take time to read the books and accompanying information. Each week of the six-week exhibition, one book that could not exist outside the specific conditions that were created in the gallery was burned and the ashes were displayed in specially made glass vases. By the end of the exhibition, all such books were burned.

In the installation Kavvadias explicitly stated that the documents neither expressed his views nor had his endorsement.

Background

Kavvadias started the project in 2005 believing that the new anti-terrorist legislation was highly problematic and represented an erosion of civil liberties – a hypothesis that he wanted to test as an artist, from the standpoint of an individual, independent investigator who has unique access through exhibition to the public, the media, the law and the policy maker.

I am not a lawyer, in fact when I started out I wasn’t sure what I was. The choices seemed to be: journalist, activist, artist. I chose the latter.”

The legislation

As the Report of the Eminent Jurists’ Panel on Terrorism, Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights 2009 noted:

Many participants at the U.K. hearing raised concerns that the breadth and the ambiguity, of the offence of ‘glorification’ create a risk of arbitrary and discriminatory application. The risk of such abuse is exacerbated by the fact that the offence applies also to past acts of terrorism and to terrorist acts occurring in other countries. Witnesses expressed concern that such wide-ranging laws reduce legitimate political debate, particularly within immigrant or minority communities.”

Aware of the grey areas the legislation created, Kavvadias’ show was an attempt to plot the margins of legality with regard to counter terrorism legislation – what can be seen, said or thought.

The methodology

Kavvadias identified the steps he needed to take to be able to demonstrate, in court if necessary, that his motivation was as an artist. The artwork was both his presentation of texts and objects in a carefully curated space, and the evidence for his defence.

Here is a brief summary of his interactions with the police, lawyers and a member of the House of Lords, who helped him to answer the underlying questions his project raised.

The Police

Having first secured support for this project from Leeds Metropolitan University where he was studying at the time, Kavvadias approached the police and had an hour-long interview with the Counter Terrorism Special Branch in Leeds. He made a record of the interview during which he went through a list of the materials he thought he could not present. He asked the police to respond to these materials during the interview. He was asking for advice, not permission.

The police tried to advise Kavvadias on what — in their view, following available guidance — he could and couldn’t collect and discussed examples of material that had been used by the police to secure convictions.

The police always had a feeling of a line – ‘if you cross the line it will be illegal and we will have to arrest you’. This is a preventative measure from the police – they want to present a line, they don’t want to give you the grey area, so that you stay safely within the legal side. Even if later the court might say – ‘no there is no case’. The police have an interpretation of the law and this understanding is later modified by a court.”

The State Machinery

Kavvadias wrote to the Press & Broadcasting Advisory Committee (DPBAC) at the Ministry of Defence (MoD) asking if he could display restricted MoD documents that he found on Wikileaks. He received the following reply:

“I have no objections from Defense Advisory Notice standpoint to your displaying the first and second pages of the subject document as part of your project.”

With this letter to support him, Kavvadias displayed the first and second page of a document, leaked by Wikileaks, that gives an idea of the level of surveillance capabilities of the UK.

The Lawyers

The first legal opinion Kavvadias sought was from Liberty and he got a very detailed letter back, explaining how the legislation can be applied, where he needed to be extremely careful and how he should position himself. “It was very illuminating and very useful and it was one point of view,” Kavvadias said.

Kavvadias then approached Gareth Pearce, a British solicitor and human rights activist, who connected him with Alastair Lyon one of her team, and subsequently talked to Matrix Chambers’ Matthew Ryder QC in detail about his project. All the lawyers he approached supported the project and thought it was an important piece of work. While they disagreed about what was the greatest specific risk, the lawyers agreed that extreme care should be taken on how the whole show would be staged.

All agreed that at the entrance of the gallery there should be a very clear public disclaimer that the artist and gallery do not advocate violence and to distance themselves from the content. It should be made absolutely clear that the exhibits were to be seen and discussed, but not recorded — no photography, no note taking — to minimise dissemination. No part of the installation should be available on the internet.

The biggest challenge was the contradictory advice – ultimately you have to make up your mind – Liberty, MR, Lord Carlile – all liked the project. No-one took an absolute position so it was my decision. I felt I had the information – the facts were in front of me and I had to make up my mind to stick with it.”

The Law Lord

Encouraged by the support from the lawyers, Kavvadias went on to one of the highest authorities in the land – Lord Carlile of Beriew, Independent reviewer of terrorism legislation UK 2011– a Law Lord. He wrote to Carlile and received the following reply:

Thank you for your letter of February 25th.

I was interested by your MA project and am sure that there is a visual art context into which counter-terrorism legislation can be put.

Artists sometimes take risks with the Law to achieve full expression, however the Law will not be suspended for such projects. When people take a close interest in terrorism websites, or sites containing material that might prove of interest to terrorists, the authorities would be negligent if they did not take an interest in such activities, if aware of them. I am sure that you are exactly as you describe, an artist acting in good faith, but the police and others will not necessarily take that at face value and understandably so.

The authorities are under no obligation to advise whether proposals made by a citizen will lead to prosecution, and there is case law to say they need not do so. Indeed the giving of such advice would be a departure from normal practice by both the police and the Crown Prosecution Service. In the event of prosecution being considered the CPS would certainly take into account Zafar1 in assessing whether there was enough evidence or whether or prosecution was in the public interest.

The best and short answer to your question is that you are unlikely to be prosecuted and if prosecuted, not convicted, if you do not break sections 57 or 58 of the Terrorism Act 2000. The responsibility for what you do is yours: I am sure you are conscious of this, and in following your studies, document what you do and why by notes.

I am sure that your course supervisors will advise you on boundaries with the advantage of knowing your work. Central St Martins is an excellent and celebrated art school and the staff there possess well-honed judgement about the boundaries between conceptual art and politics and the Law.

I am sorry that I cannot answer your question more directly, but I am afraid that the Law is no less conceptual than fine art.

Best wishes

Yours sincerely

Signed –

Alex Carlile.

1. R v Zafar & others [2007] Imran Khan and Partners represented Aitzaz Zafar when in 2007 he, together with Irfan Raja, Awaab Iqbal, Usman Malik and Akbar Butt were jailed for between two and three years each by the Old Bailey for downloading and sharing extremist terrorism-related material, in what was one of the first cases of its kind. The prosecution alleged that they had collected extremist material for the purposes of terrorism. The men argued that they had no real terrorism links and were driven by intellectual curiosity. Four of the men were students at the University of Bradford. Following their convictions, the men appealed and on the 13/02/2008 the Court of Appeal overturned their convictions. In their ruling, the three Appeal Court judges said the trial jury should have been told to decide whether there was a connection between the extremist literature and a clear terrorist plan. http://www.ikandp.co.uk/ViewCaseStudy.asp?CaseID=76

Having managed to engage a high level politician and lawyer, Kavvadias felt that it would be extremely hard for the police to characterise him as someone who was acting recklessly.

The Gallery

10 Vyner Street gallery owner Peter Gallagher-Witham was interested in freedom of speech and felt it was worth investing in and thought it was a good work of art. He also felt that it was controversial and would attract attention. Despite the gallery owner’s belief in the work, he had a lot of reservations; he was worried that the police would come to the gallery and he would be accused of dissemination of terrorism.

He really wanted some sort of reassurance, but there is not an absolute reassurance. There are steps that can minimize risk. I never expected a public gallery to take this work because of the nature of the work being too contentious.

This was the last exhibition in 10 Vyner Street, which closed at the end of Kavvadias’s show.

The Reaction

Like most artists, Kavvadias wanted publicity for his work, but in this case, it was not just the exposure for the work that he was looking for. The press was interested because Lord Carlile, a senior law lord, had responded to an artist; this was newsworthy. The Guardian wrote an article which took the project into the public domain, opening it to scrutiny by an infinitely wider group, including the police. During the exhibition, Sir Allan George Moses, a former Court of Appeal judge, visited the gallery and left a positive comment. The police did not openly visit the gallery.

There were no legal repercussions for Kavvadias as a result of the exhibition.

21 Jul 15 | Art and the Law Case Studies, Artistic Freedom Case Studies

Exhibit B (Photo: © Sofie Knijff / Barbican)

This is an account of the policing of the demonstration organised by Boycott the Human Zoo Campaign on the opening night of Brett Bailey’s theatrical installation Exhibit B presented by the Barbican at the Vaults Waterloo. Written by Julia Farrington, associate arts producer, Index on Censorship, it is part of Index’s short series of case studies looking into policing of arts events in the UK.

The case studies have been written to accompany Index on Censorship’s information packs on the legal framework underpinning artistic freedom of expression in this country. In this case the report relates to the pack on Public Order which addresses the rights, responsibilities, roles and rules around policing of public order incidents in response to artistic expression.

The production was closed on the advice of the police to the organisers of Exhibit B: to cancel the opening night 23 September 2014, and all subsequent performances 24–27 September. Immediately prior to the Barbican dates, the work was shown as part of the Edinburgh Festival. A 2012 production of Exhibit B drew condemnation in Berlin.

Interviewees

Louise Jeffreys, director of arts Barbican Centre

Lorna Gemmell, head of communications, Barbican Centre

Kieron Vanstone, director, The Vaults

Sara Myers, journalist, who started the Boycott the Human Zoo campaign

Lee Jasper, policing director for London 2000-2008 Mayor of London office, who liaised with the police on behalf of the Boycott the Human Zoo campaign.

Julia Farrington also approached the British Transport Police (BTP) and the Metropolitan Police (The Met). Farrington received written answers from Assistant Chief Constable Stephen Thomas (BTP) and applied for answers via Freedom of Information requests as recommended by The Met. (The answers from FoI are outstanding, though in the main the same ground is covered by BTP.)

Background

The Barbican’s publicity material described Exhibit B as: “a human installation that charts the colonial histories of various European countries during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when scientists formulated pseudo-scientific racial theories that continue to warp perceptions with horrific consequences.”

Boycott the Human Zoo is a coalition of anti-racism activists, trade unions, artists, arts organisations and community groups. The campaign, which was formed in response to Exhibit B, objected to the work on the following grounds:

“The human zoo is an ugly stain on European history. The recreation of viewing Africans as caged exhibits is a pastime society long lost the stomach for. On 23rd Sept 2014 artist Brett Bailey and the Barbican, are set to resurrect this unjustifiable practice. Despite the condemnation of race campaigners, they [the Barbican] remain insistent that this piece is ‘challenging racism and cultural ‘othering”.”

Online petition with change.org

Boycott the Human Zoo set up an online petition on change.org calling on the Barbican to decommission the work and withdraw it from their programme. The key objections named in the petition were:

“[It] is deeply offensive to recreate ‘the Maafa – great suffering’ of African People’s ancestors for a social experiment/process.

Offers no tangible positive social outcome to challenge racism and oppression.

Reinforces the negative imagery of African Peoples

Is not a piece for African Peoples, it is about African Peoples, however it was created with no consultation with African Peoples”

The petition was signed by over 22,000 people.

The Barbican response

On 22 September, the Barbican issued a response to Boycott the Human Zoo’s online petition, which concluded:

“[We] accept that the presentation of Exhibit B has raised significant issues and undertake to explore these further. But we cannot accept that the views expressed, however strongly felt, should be a reason to cancel the performances. We have an undertaking to our committed performers and to our audiences who wish to explore these difficult subjects. We state categorically that the Barbican is not neutral on the subject of racism; we are totally opposed to it and could not present a work that supported it.

“Finally, we fully accept your right to peaceful protest if you disagree with this conclusion; in return we would ask that you fully respect our performers’ right to perform and our audiences’ right to attend.”

Dialogue

Boycott the Human Zoo campaigners were in communication with senior management at the Barbican from the launch of the campaign about their intended actions. Campaigners also contacted the police about planned picketing. On 11 September, Barbican senior staff and board members met with Boycott leaders to discuss their campaign and their opposition to Exhibit B.

The night before the opening of Exhibit B, Nitrobeat, the black theatre company who had been responsible for casting the show, organised a public debate at Theatre Royal Stratford East in response to the boycott. Louise Jeffreys spoke on the six person panel in support of Exhibit B; Sara Myers spoke for the Boycott the Human Zoo Campaign. About 150 people attended.

Police involvement in the lead up to the opening of Exhibit B

The Boycott the Human Zoo campaign went live on 19 August. As soon as he was made aware of it, Kieron Vanstone, director of The Vaults, anticipated the possible need for additional security. He met with the Barbican’s head of security to discuss and contacted British Transport Police (BTP). Kieron Vanstone said the police were slow to respond to his requests.

Louise Jeffreys commented that: “Considerable effort was put in by Kieron and Nigel Walker (head of security at the Barbican) to make sure that the police were aware of … what might happen there. It wasn’t that they weren’t informed, they absolutely were.”

Three different police forces were involved in policing the installation:

British Transport Police

The Vaults is directly under Waterloo station, and falls under the jurisdiction of BTP. It is a large space built into the railway arches approached by a tunnel. Assistant Chief Constable Steve Thomas of the BTP, who responded to Index’s questions relating to the policing of the event, said that “this case was dealt with as a low level event by our ‘B’ Division Operations Unit and their Neighbourhood Policing Unit at Waterloo”.

Regarding the planning of police resources for the opening night, the following is an extract from the e-mail written to Kieron Vanstone on 19 September: “My Operations department are in contact with the Metropolitan Police planning team and I have not been informed regarding extra resources for the event as yet. I have 2 PCs [Police Constables] and 4 PCSOs [Police Community Support Officers] on duty on Tuesday plus 1 Sergeant. I can’t promise all personnel to be there but there will be a police presence.”

Metropolitan Police

While BTP has jurisdiction over the Vaults, as ACC Thomas explained: “the roadway and areas where protestors were expected to gather are within the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police Service.” On 22 September, Lee Jasper of the Boycott met with Sgt Tom Cornish of The Met and Kieron Vanstone to agree to a plan for the picketing. The three visited the venue together and decided where the barriers should be placed. Kieron Vanstone noted that the meeting was very affable and everyone was in agreement. At the time, Lee Jasper said that he thought the venue was going to be problematic.

City of London Police

The Barbican Centre itself comes under the jurisdiction of the City of London Police. Police attended two protests at the Barbican, both of which went ahead without incident. On 14 September, the City of London Police attended a Boycott the Human Zoo campaign protest of about 165 people outside the Barbican when campaign leaders attempted to deliver a hard copy of the petition before the production opened. The Barbican directed the campaigners to hand it in to the head of security. This was rejected by the boycott organisers. It was the campaigners’ understanding that they would hand it to a member of the Barbican board, who was present on that occasion but did not come down to receive the petition, they said. The Barbican told Index that there was no board member present at the time. Boycott the Human Zoo returned to the Barbican on 16 September with about 50 people and delivered a hard copy of the petition to Barbican Managing Director Sir Nicholas Kenyon. There was a low level police presence on both occasions. The City of London Police also sent a unit of officers to the Barbican Centre on the opening night, in case there was protest at that location.

ACC Thomas, commenting on the allocation of policing on the night, said: “Like BTP, the Metropolitan Police Service decided to police the event with their Waterloo Neighbourhood Policing Team – a decision based upon the information and intelligence known to them at the time and upon their discussions with the organiser of the protest. Once requests were made by the officers at the event for assistance, more Metropolitan Police Service and BTP officers attended to deal with the protesters. Often when an event happens and there is a shared event footprint, there is an agreement to place all officers involved under the command of one of the Police Forces involved. This was not done on this occasion as both Forces anticipated a low level peaceful protest that did not necessitate this approach.”

Policing on the night

Allocation of officers

On the opening night of the installation, just one of the two BTP PCs, allocated to the picket, attended. ACC Thomas stated: “The Sergeant, two Constables and four PCSOs mentioned in the e-mail (see above) were the entire shift on duty at Waterloo Station that evening. Obviously, the shift had other operational duties to perform and there were calls from the public to deal with. As such, it was never the intention for the entire shift to be posted to the event. In the planning for the event and on the night, an operational decision was made to post one Constable and two PCSOs to the event.”

At the entrance to the venue

There were problems from the start of the demonstration with implementing the plan agreed by everyone the previous day. Accounts differ as to why this broke down. According to Lee Jasper, the barriers were not configured as agreed; Kieron Vanstone, director of The Vaults, says the plans were followed, but the protesters breached the barriers. But the result was the demonstration was right up against the doors to the venue. There is CCTV footage of the protesters up against the doors of The Vaults, and the organisers were concerned that they were trying to force their way into the building.

“We were never interested in what was happening inside. We didn’t want to get in. We wanted to stay on the outside and stop people going in,” said Sara Myers.

Seven security guards were caught between the doors and the protesters. At this point, it became clear to Kieron Vanstone that the scene at the entrance had “descended into chaos.” At around 6:30pm, just when the first performance was scheduled to begin, he decided to evacuate the building: performers, audience and senior Barbican staff, including Louise Jeffreys and Nigel Walker, head of security.

Call for additional police

The PC on duty called for backup officers. ACC Thomas reported “that ‘about’ 12 BTP officers and 50 Metropolitan Police Service Officers attended the event in response to the ‘calls for assistance’ from the officers dealing with the protesters. However, it is not possible to confirm exactly how many officers … actually attended this event … because the radios of both Forces do not work in the tunnel and so exact numbers may not have been recorded.”

When Lee Jasper of the Boycott saw the additional police arriving at the end of the tunnel, he went to meet them. The police, who had brought dogs with them, were preparing to clear the tunnel. “I spoke to Tom Cornish [of The Met] and made it clear that I thought that would be the biggest mistake. The tunnel amplified the sound of the drums and the whistles, there were a lot of people in a small space, feelings were running high and the situation could escalate. I repeated my view that the event should be closed down,” Lee Jasper said.

Inspector Nick Brandon, the senior officer in charge from BTP, went to speak to the campaign organisers. Sara Myers told Index: “[Brandon] didn’t know anything about the show or what had happened over the past month, so I told him about the boycott. He asked me what we wanted and I said we wanted the show to be closed down. And that if it wasn’t closed down, we would come back every evening to picket the show. He told me that they hadn’t got the resources to police this every day. He said ‘we need to be out fighting crime. This is much ado about nothing, and we haven’t got the resources to police it’.”

Police advice

After evacuating the building, Kieron Vanstone returned to the main entrance to find that backup officers had arrived. He described the scene as: “Fifty police, riot dogs, helicopters overhead – just a huge police presence. I was in real shock. The BTP inspector asked me what I would like to do… I couldn’t see a way that we could avoid the protest [continuing], so then he recommends that he doesn’t think we should continue the show for the rest of the duration”.

Kieron Vanstone called the Barbican’s senior management team, who had returned to the Barbican Centre, and passed on the recommendation of the police to discontinue the show for the whole run. The team asked his opinion, and Vanstone said he couldn’t see a way to continue the show.

“That was definitely influenced by the amount of fear that had been put into me as well as that I couldn’t physically see a way to get people into the building in a safe way,” Vanstone said. “I kind of know as well that the police used me to make that decision to get the protesters to disperse.”

ACC Thomas reported that Kieron Vanstone asked Inspector Brandon’s advice and he was told “that the production should cease at that location and another location should be considered.” ACC Thomas added:

“Of course, this was ‘police advice’ and the final decision (as it always is) to continue or cancel an event lies with the event organiser. On 23rd September the event organiser appears to have decided to cancel the event that night and on all subsequent nights, based upon the advice of Inspector Brandon.”

As the senior management team travelled back to the Barbican, as yet unaware of the police advice, they had been determined to open the show the next night. Louise Jeffreys said: “We need[ed] to get the police behind this again and it was important that we went back and tried again [the following night].”

But when Kieron Vanstone got in contact to tell them of the recommendation, the senior management team agreed to follow the police advice.

When asked about the police advice to cancel all five performances, ACC Thomas explained that Inspector Brandon who attended the Vaults during the protest, based his opinion on “his assessment of the venue entrance in a narrow arch of some 50 foot wide and 400 foot long, with very poor lighting and no available police radio communications (due to the tunnel roof), the difficulty of ticket holders passing through the protesters, the difficulty of ‘controlling’ the 150 or so protesters in that environment and the large number of police officers it would have required.”

Request for a written guarantee from the venue

Sara Myers said that one of the Boycott partner organisations requested written confirmation that the event would be closed for all subsequent planned performances, adding that they would not disperse until this confirmation had been produced.

Five police officers entered the Vaults to talk to Kieron Vanstone. He commented: “They made me do a written letter, and go back out to the protesters, [which is online at Youtube], and present the written letter to say we were not going to continue the show. I didn’t actually do the letter straight away. I went out there and spoke to [the protesters] first, then came back in…They [the police] came back to me and go ‘No, we need to write the letter’. So very forceful about that, [they] very much need to use me.”

Assessment of the police decision

The Barbican felt that the policing had been inadequate and disorganised. Louise Jeffreys said: “Our [risk assessment] never had anything ‘What if the police don’t turn up?’…. It didn’t even cross our minds that that would be something we would have to deal with, so of course … we weren’t really prepared. So it happens in a second and then because it’s happened you could change it [the decision to accept the police’s recommendation], but changing it is a huge, huge thing.”

Sara Myers of the Boycott the Human Zoo campaign was pleased that they had gotten the result that they wanted and felt well supported by the police.

Sara Myers commented: “It gave us a victory with the police – it showed the police supporting black people’s right to protest, and it gave us hope then we might get another victory another time. The negative portrayal came from the media, never from the police. I had a long conversation with the police on the night. They had been called to investigate an alleged assault, but no arrests were made, no damage to property, but we were portrayed as this violent mob [in the media].”

The Barbican senior management team met with Kieron Vanstone the following day to consider their options, including whether they could mount the exhibition elsewhere, but it was agreed that it wasn’t feasible. They also questioned the consequences of going against police advice.

The Barbican’s Head of Communications Lorna Gemmell said: “I think the question is ‘How does any arts organisation take the decision to go against police advice in the scenario where there is actual risk to public safety?’. That’s what we were discussing the next day.”

The Barbican decided to stand by the decision reached the previous night, rather than contest it. They were told the next day that the police were investigating violent disorder associated with the protests. They were constrained about what they could say publicly because of the investigation.

Louise Jeffreys commented:

“Knowing that made it even harder to try and get the decision overturned and it also made us believe that it [had been] unsafe. Because why would you be pursuing violent disorder if it was safe?”

The Barbican issued a statement:

“Last night as Exhibit B was opening at the Vaults it became impossible for us to continue with the show because of the extreme nature of the protest and the serious threat to the safety of performers, audiences and staff. Given that protests are scheduled for future performances of Exhibit B we have had no choice but to cancel all performances of the piece.”

In retrospect, Louise Jeffreys thinks that “the case should have been escalated with the police”, but Barbican’s senior management felt constrained and, to an extent, reassured that action was being taken by the police. “We felt it was being handled because of the investigation into violent disorder,” Jeffreys said. Statements by the security guards on duty on the night were subsequently withdrawn. The police inquiry was dropped.

The Boycott campaign also issued a statement on the closure of the installation:

“#boycottthehumanzoo would like to make it clear that at no point during the protest was anyone hurt or threatened. Police attended the scene after reports of violence, but seeing that the blockade remained peaceful, made no arrests.”

Complaint from an audience member

There was an investigation into a complaint by a member of the public to the police about the policing on the night. In response to an Index question about this, ACC Thomas wrote:

“The complainant had purchased a ticket for the event on 23rd September 2014. When it was cancelled, they complained that: ‘Police failed to ensure the legal right of freedom of expression by those persons who had wished to see the play.’ The complaint was made to the Metropolitan Police Service and passed onto BTP. The complaint was investigated ‘locally’ on B Division of BTP and the complaint was found to be ‘partially upheld’. The complainant was informed of this and provided with a copy of the Investigating Officer’s report. The complainant appears to have been satisfied with this.”

The Barbican asked for a written statement from the police, confirming their recommendation, which they did not receive.

21 Jul 15 | Art and the Law Case Studies, Artistic Freedom Case Studies

A scene from Can We Talk About This? (Photo: Matt Nettheim for DV8)

As part of our work on art, offence and the law, Julia Farrington, associate arts producer, Index on Censorship, interviewed Eva Pepper, DV8’s executive producer about how she prepared for potential hostility that the show Can We Talk About This? might provoke as it went on tour around the world in 2011-12.

Background

Can We Talk About This?, created by DV8’s Artistic Director Lloyd Newson, deals with freedom of speech, censorship and Islam. The production premiered in August 2011 at Sydney Opera House, followed by an international tour of 15 countries — Sweden, Australia, Hong Kong, France, Italy, Austria, Germany, Greece, Slovenia, Hungry, Spain, Norway, Taiwan and Korea and the UK between August 2011 and June 2012 — and was seen by a 60,000 people.

Extract from publicity of the show:

“From the 1989 book burnings of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, to the murder of filmmaker Theo Van Gogh and the controversy of the ‘Muhammad cartoons’ in 2005, DV8’s production examined how these events have reflected and influenced multicultural policies, press freedom and artistic censorship. In the follow up to the critically acclaimed To Be Straight With You, this documentary-style dance-theatre production used real-life interviews and archive footage. Contributors include a number of high profile writers, campaigners and politicians.”

Q&A

Farrington: How did you set about working with the police for this tour?

Pepper: We focused on the UK with policing; I didn’t speak to any police forces in other countries at all, just in the UK cities we toured to: West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds; Warwick Arts Centre; Brighton Corn Exchange; The Lowry in Manchester and the National Theatre in London. But we did have a risk assessment and risk protocol that we shared with every venue we went to. We let them know the subject matter and the potential risks: security, safety of the audiences, media storms, safety of the people who were working on the show. They dealt either with their in-house security, or, in the UK, they would often alert the police as well.

Farrington: How did your preparations with police vary around the UK?

Pepper: We started with the Metropolitan Police, about six months before and told them our plans and that we would also contact other police forces. The National Theatre had their own contacts with the police who were already on standby. We still kept the MET events unit informed, but they [National Theatre] dealt with the police themselves. They were much more clued up, they had a head of security whom I briefed; we talked quite a lot. I made sure that he was copied in when anything a bit weird came up on the internet.

Our first venue was Leeds and we approached them about six weeks before the UK premiere. There was a bit of nervousness around Leeds, because of the larger Muslim population in the area. But we were only just beginning our liaison with the police and it took a little time to get a response. In the end we approached senior officers, but they often didn’t engage personally, just put us in touch with the appropriate unit to deal with.

Farrington: They didn’t see it as that important?

Pepper: They liked to be alerted that something might happen and they assured us that they were preparing. The venues also had their own police liaison; sometimes there was a bit of conflict if they had their own. I probably ruffled a few feathers when I went to a more senior officer.

Our starting point to the police was a very carefully worded letter which set out who we were. We didn’t ask permission to put it on we just alerted them that we might need police involvement. I did have some calls and a couple of meetings with officers, where they reiterated what is often said, which is that the police’s mandate is to keep the peace. It was made clear that they have as much of a duty to those people who want to protest or potentially might want to protest, as they have to allow us to exercise our freedom of expression. In Leeds nothing happened but there was a certain amount of nervousness around it.

Farrington: Where – at the venue?

Pepper: I think we were probably a bit nervous, and the police took it seriously enough. We had contact numbers to call. They were very much in the loop of the risk assessment.

Farrington: Was there a police presence on the night?

Pepper: I don’t remember seeing anybody. There was security of the venue of course, but regional venues only go so far with security. With some venues we were a little insistent that they get somebody upstairs and downstairs for example.

Farrington: And search bags, that kind of thing?

Pepper: We insisted people check in bags. The risk protocols weren’t invented for Can We Talk About This? They were really invented for To Be Straight With You [DV8’s previous show] and just tightened up for Can We Talk About This?. The risk protocols are just bullet points to get people thinking through scenarios.

Farrington: In general how would you describe your dealings with the police?

Pepper: I think generally supportive but we came to alert them that we might need them – there wasn’t a crisis. They said ‘thanks for letting us know let us deal with it.’ We would have quite liked to go through their risk assessments, but that didn’t happen. I think we were a little bit on their radar. They offered to send round liaison people to discuss practicalities around the office – stuff we hadn’t really thought about. It was a little bit tricky to get their attention.

The things we asked them to look out for were internet activity, if there was something brewing; sounds terribly paranoid. If there were issues around our London office or tour venues like hate mail, suspicious packages and then protests. So protest was just one thing our board was concerned about.

Farrington: Did you do anything else with the venue to prepare them for a possible hostile response from the media or a member of the public?

Pepper: I asked every venue artistic director or chief executive to prepare a statement. Lloyd would have been the main spokesperson for us if anything went wrong, but for a regional venue it is important that you are ready with a response and they all did that.

Farrington: What kind of thing did they say?

Pepper: We have supported this artist for the last 20 years. Lloyd has always been challenging in one way or another. This time he is challenging about this and we are going with him.

Farrington: Did you have any contact with lawyers?

Pepper: We looked carefully at the contents of the show. We had used interviews with real people and we wanted to be sure that nothing said was libellous or factually incorrect. So we had things looked at. The lawyer would say have you thought about that, did you get a release for this, are you using this from the BBC, do you have permission, have you spoken to this person, does he know you are doing it? And sometimes it is yes and sometimes it was a no.

Farrington: They pointed out some bases you hadn’t covered?

Pepper: Maybe one. We were really good and a bit obsessive. Sometimes we thought we didn’t have to ask because the information was in the public domain anyway, based on an interview that has been online for ten years for example. And the lawyer would or wouldn’t agree with that. It was good for peace of mind. That’s the thing with legal advice it doesn’t mean that nobody comes after you, because the law isn’t black and white.

Farrington: Were there some venues that you took the show to that didn’t think it was necessary to make special preparations?

Pepper: We always made them aware and we let them handle it. There are certain things that we always did. We asked them to consider security, and certainly PR. I was quite concerned that it would be a big PR story and then out of the PR story, as we saw with Exhibit B, comes the police. The protests don’t come from nowhere usually, somebody comes and stirs things up.

Farrington: Did you prepare the venue press departments?

Pepper: Yes we did, and we quite consciously had interviews, preview pieces before hand, where Lloyd could give candid interviews about the show. Almost to take the wind out of people’s sails, to put it out in the open so nobody could say they were surprised.

Farrington: How did you prepare with the performers for potential hostility?

Pepper: We talked through the risk procedure with them. We also got some advice from a security specialist, about being more vigilant than usual, noticing things that are out of the ordinary; if somebody picks a fight in the bar after the show, find a way to alert the others. So yes, the security specialist had a meeting with us here in the office, but also came up to Leeds to talk to the performers.

Farrington: Did it create a difficult atmosphere?

Pepper: It did yes, it got a bit edgy. Next time I would not do it around the UK premiere. It took a long time to set all of this up. To find the right people, to get people to take it seriously, to have meetings scheduled.

Farrington: It took time to find the right kind of security specialist?

Pepper: It also took a little while to get straight what we needed. We probably tried to figure it out for ourselves for a long time. And then got somebody in after all, just as maybe we, or the board got a bit more nervous. When you talk about protests you always worry about the general public, but as an employer there are the people who you send on tour who have to defend the show in the bar afterwards, potentially they are the targets.

Farrington: But they were behind the show?

Pepper: Yes, undoubtedly. But it’s an uncomfortable debate. There were so many voices in that show and you didn’t agree with every voice and it was never really said what really is Lloyd’s or DV8’s line. I would say that all the dancers were fine, but sometimes if somebody corners you in a bar it gets squirmy. No one is comfortable with everything.

Farrington: Can you summarise the response to the show?

Pepper: We had everything from 1 to 5 stars. We had people that loved the dance and hated the politics, who loved the politics and hated the dance. Occasionally somebody liked both. Occasionally somebody hated both. The show was discussed in the dance pages, in the theatre pages and in the comments pages. So in terms of the breadth and depth of the discussion we couldn’t have been more thrilled. Then we had dozens of blogs written about the show. For us Twitter really started with Can We Talk About This? and it was a great instrument for us. Social media was largely positive, though some people were picking a fight on Facebook at some point. It was very, very broad and very widely discussed.

Farrington: And did you interact with Twitter or did you let it roll?

Pepper: Mostly we let it roll. As part of the risk strategy we had a prepared statement from Lloyd which was very similar to the forward in the programme and anybody who had any beef would be redirected to the statement.

Farrington: Did the venues take this performance as an opportunity to have post show discussion and debate?

Pepper: Lloyd prefers preshow talks because he doesn’t like people to tell him what they thought of the shows. Quite often there is a quick Q&A before. In UK, we had one in Brighton [organised by Index] and one at the National. We had fantastic ones in Norway after the Breivik killings. In Norway they weren’t sure it was relevant and then the killings happened and then I got the call to say now we need to talk about it.

But having pre-show talks is certainly how we decided to deal with it. There is a conflict with having a white middle-aged atheist put on a show about Islam. But the majority of voices in the show were Muslim voices of all shades of opinion. It wasn’t fiction. It was based on his research and based on people’s stories – writers, intellectuals, journalists, politicians and who had a personal story to tell

Farrington: How did you prepare work with the board regarding potential controversies?

Pepper: Really the work with the board started with the previous show To Be Straight With You that already dealt with homosexuality and religion and culture; how different communities and religious groups make the life of gay people quite unbearable, internationally and in this country. And even then, we started to say, ‘can we say this? are we allowed to criticise these people like this?’ and out of that grew the ‘yes, I do want to talk about this’ because if we don’t a chill develops. Can We Talk About This? was a history about people who had spoken out about aspects of Islam that they were uncomfortable with or against and what happened to them.

Farrington: What kind of board do you need if you are going to be an organisation that explores taboos like this?

Pepper: We have got a fantastic board; it is incredibly responsible and so is Lloyd. There is a very strong element of trust in Lloyd’s work. They wouldn’t be on the board if they didn’t support him. But, as employers, they are aware of their responsibilities to everyone who works for us. As a company we have to be prepared in the eventuality that there is a PR or security disaster. What we were really trying to do was avoid that eventuality. We will never know. Maybe nothing bad would have happened. I think that Lloyd now wishes more people had seen it, that a film had been made, that it was more accessible to study by those who want to. He thinks that maybe we were a bit too careful. But as an organisation, as DV8, as an employer I think that we did the right thing by looking after people.

Farrington: What advice could you give to prepare the ground for doing work that you know will divide opinion and you know could provoke hostility?

Pepper:

E: If you can anticipate this you already have an advantage, but it’s not always possible to second-guess who might find what offensive. But if you know, I would suggest you ask yourself what buttons you are likely to push; you have to be confident why you are pushing them – usually in order to make an important point. It’s a good idea to articulate this reasoning very well in your head and on paper. Then you have got to be brave and get on with your project. Strong partners are invaluable, so try to get support. But in the end it is about standing up and being able to defend what you do.

Farrington: So you think you could have gone a bit further?

Pepper: I think if you prepare well you could go a bit further. I don’t think there is a law in this country that would stop you from being more offensive than we were. Every artist has to decide for themselves what they want to say and why they are saying it, and if they can justify it they can go for it.

21 Jul 15 | Art and the Law Case Studies, Artistic Freedom Case Studies

From Behud – Beyond Belief by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti

By Julia Farrington

July 2015

In the early stages of Index on Censorship’s programme looking into art, law and offence, we wrote a case study about Coventry’s Belgrade Theatre, which premiered the production of Behud – Beyond Belief, 2010. The play is Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s artistic response to the experience of Behzti – Shameless, her previous play, being cancelled by Birmingham Rep in the face of protests.

Superintendent Ron Winch of Coventry Police was the officer in charge of policing the Behud premiere. Julia Farrington, associate arts producer, Index on Censorship, talked to Winch about working with the community and the theatre to ensure that Behud went ahead without incident. Winch provided interesting insights into how the police view the right to artistic freedom, particularly in comparison to the right to freely express political views.

Winch: The role of the police is to maintain law and order, to prevent crime and disorder. But the police have a wider democratic responsibility both to facilitate freedom of expression and at the same time to understand that it may cause offence to others. The community is looking to the police to prevent the play from going ahead because they believe it’s offensive. It could be blasphemous. And the theatre is saying to the police that the playwright has a right to express her views. The fact that Behud wasn’t as controversial a play as Behzti was probably due to the work that we did going into the community and reassuring people. It was successful from our perspective; there were no public safety concerns and the play went ahead.

Farrington: So you were weighing up the right of freedom of expression against other potentially conflicting calls on your time and your resources?

Winch: For me it was about understanding what policing is in a liberal democracy. We police by consent. That is not about police preventing freedom of expression, as long as it is lawful. If I didn’t believe in freedom of speech I wouldn’t be in this profession. And yet I am acutely aware of how sensitive some sections of the community are, especially when they see their faith being questioned, highlighted and in their view, blasphemed.

Farrington: Do you think that freedom of expression in this country is endangered if it requires this degree of negotiation and investment of time and resources on everybody’s part?

Winch: My professional view and my personal view are different. My personal view is that individuals have the power to press the off button. There are all sorts of things, especially in the media, with 24-hour news and the internet, that people would prefer not to see and it is hard for the state to control. And you have to ask whether censorship is something that the state should be concerned with. The state is always trying to legislate against things that it sees as harmful, either to the political establishment or the economic or social well-being of the community at large. But with diverse communities, all of whom have different views of what is acceptable, it is going to be very difficult for the state to create laws that they then expect the police to enforce.

Farrington: You could say that it is not the role of the state to legislate for people’s sensibilities – the idea that people believe that they have a right not to be offended. In a way that is what you were balancing in the case of Behud.

Winch: It might be surprising to you coming from Index on Censorship – you wouldn’t expect a police officer to be making these kind of decisions around a play.

Farrington: I would have expected them to be taken by someone in the council. But when I spoke to Clive Towndend of (Coventry City Council) Events Committee he emphasized that this was a policing issue.

Winch: As I said earlier, my decision was very clear. I faced a situation where if I didn’t do the consultation I might have had to react in an emergency – which is so much harder and more challenging than when you have had time to prepare.

Farrington: So you had police officers at the back of the theatre?

Winch: We had sufficient number of police officers on duty to manage the risk as we perceived it. But those officers were in a very low profile kind of mode.

Farrington: In the last few days before the production opened there was a communication between your colleagues in Birmingham and yourselves suggesting the threat of violence.

Winch: The threat was always there. If a group of people wanted to disrupt an event, especially a controversial event, then if they have the support they could probably do that, whether or not it was justified.

Farrington: I’d like to talk about the question of fees to cover the cost of guaranteeing the safety of the theatre. As I understand it, the bill was £10,000 a night for the cost of policing.

Winch: It wasn’t that much. In fact the theatre was not charged for the policing.

Farrington: But initially you assessed that it would cost £10,000 a night in policing and you wanted to pass that cost onto the theatre. The theatre argued that, as a not-for-profit rather than a commercial organisation, such a charge would make it impossible for the play to go ahead [and an act of de-facto censorship on financial grounds]. The fee was reduced to £5,000 and eventually as I understand it, the fee was waived altogether.

Winch: My police constable in charge of planning our operations works in other areas – for example football matches – took the view that if we were being asked to police a private event there might be costs. I think that is legitimate. Some of the community might say whilst I have got police officers enabling, or being seen to enable, a controversial play, that means that officers are not dealing with other matters. However, as things moved on, as the risks changed because of the dialogue and the meetings with the safety advisory group, I took the decision that we wouldn’t charge for policing. But what it categorically wasn’t about was the police being seen to incur costs on an organisation or theatre to prevent putting on a play.

Farrington: If you have a political protest that is planned for Saturday afternoon going through the centre of town, could you charge that political party for policing?

Winch: No, that would be very different. It is entirely fair that a profit-making private enterprise that needs to use public resources to enable their business interests to go ahead – for example in the case of a football match – be charged for the privilege. On the other hand, in the case of a political party that is not making any profit, then it is entirely appropriate that the resources of the state enable it. There is a distinction.

Farrington: But many theatres are not-for-profit charities and are perhaps more comparable to a political party. They promote and facilitate artistic expression, just as political parties promote and facilitate political expression. Both have to raise funds. Is there a category within your assessment for charitable not-for-profit arts organisations?

Winch: Ultimately it comes down to professional judgement, based on threat and risk around events. And the risk initially with this play was high, though the threat really did recede as we did the work.

Farrington: But it was a discretionary judgement.

Winch: But then so much of policing is.

Farrington: It could have gone the other way – Behud could have been pulled. Whereas in the case of a political party, even if the politics are horrible and you don’t agree with them, you don’t interfere. There seems to be an imbalance.

Winch: I don’t know about imbalance. But how would you define what type of event should be supported by the public purse? We have had enough difficulty trying to define when football clubs, multi-million pound enterprises, should pay for policing. If we open it out to all walks of public life it is just going to be too complicated. This is where we rely on discretionary judgement of professionals; society expects them to make those rational informed judgments, as I did in this situation.

Farrington: But you wouldn’t exercise the same discretionary judgment about a political party?

Winch: You could if the political party wanted to march; there is legislation around that because there are public safety considerations. If a political party wants to make a static protest there is very little you can do to prevent it from happening in terms of the law.

Farrington: But is a static protest of political expression that different from a static protest of artistic expression – in other words a play. There seems to be more structure, more acceptance and more clarity around political expression than around artistic expression, which leaves theatre vulnerable to professional discretion preventing it from going ahead.

Winch: I would not welcome legislation defining when and where we should be involved in artistic expression. I don’t think that is the right area for the state to be looking at.

Farrington: But what if it is about protecting the right to artistic expression?

Winch: But it’s about the evolution of what is considered inappropriate, and that changes. I think freedom of expression is protected – it has a natural element of protection around it and a natural censorship as well.

Farrington: And that is your consensual policing. You police by consent. You have antennae and connections tuned in.

Winch: Absolutely. My accountability in the Behud case was to the community in the widest possible sense. I had very little accountability in terms of legislation. It would just be too difficult in today’s society.

Farrington: After the G20 there was a big shift, wasn’t there, in terms of the right to protest was more thoroughly supported?

Winch: You have to look at what the law says about when and where you need to intervene. The G20 was a different set of circumstances to what we are facing locally. We live in a changing world and we have to respond to those changes.

Farrington: Nowadays we are more aware of hurt to people’s feelings and sensibilities and that’s where it becomes complicated.

Winch: It’s a very difficult area for professionals to negotiate.

Farrington: Nonetheless this play wasn’t like a football match and charging for policing would certainly have stopped the play from going ahead. The question for me is what happens when there are more constraints on resources? The decision might not go that way and the play might not go on.

Winch: I can only really speak about this specific case, because if an event like this doesn’t go well then potentially I would have to put more police officers onto the streets to maintain the security of the theatre. I think what happened with Behud was a wake up call for the theatre to recognise that actually the police are not the enemy, out to prevent freedom of speech, but very much helping to facilitate it – from a very balanced perspective. I think the wider question is: what do we want our police to do in a liberal democracy? I think policing needs to reflect the changing norms in society. Things that wouldn’t have been acceptable 20 years ago, especially around questions of morality, are now acceptable.

21 Jul 15 | Art and the Law, Art and the Law Guides, Campaigns, Index Reports

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This guide is also available as a PDF.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Preface

Freedom of expression is essential to the arts. But the laws and practices that protect and nurture free expression are often poorly understood both by practitioners and by those enforcing the law. The law itself is often contradictory, and even the rights that underpin the laws are fraught with qualifications that can potentially undermine artistic free expression.

As indicated in these packs, and illustrated by the online case studies – available at indexoncensorship.org/artandoffence – there is scope to develop greater understanding of the ways in which artists and arts organisations can navigate the complexity of the law, and when and how to work with the police. We aim to put into context the constraints implicit in the European Convention on Human Rights and so address unnecessary censorship and self-censorship.

Censorship of the arts in the UK results from a wide range of competing interests – public safety and public order, religious sensibilities and corporate interests. All too often these constraints are imposed without clear guidance or legal basis.

These law packs are the result of an earlier study by Index, Taking the Offensive, which showed how self-censorship manifests itself in arts organisations and institutions. The causes of self-censorship ranged from the fear of causing offence, losing financial support, hostile public reaction or media storm, police intervention, prejudice, managing diversity and the impact of risk aversion. Many participants in our study said that a lack of knowledge around legal limits contributed to self-censorship.

These packs are intended to tackle that lack of knowledge. We intend them as “living” documents, to be enhanced and developed in partnership with

arts groups so that artistic freedom is nurtured and nourished.

Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive, Index on Censorship

Foreword by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti

There is art that soothes, pleases and comforts and there is art that prods, pokes and disturbs. Both kinds can be magical and they both need to

be available to audiences. I have always been attracted to taboo subjects and I have a visceral desire to question and understand that part of the human condition which is abhorrent and difficult. Ignoring the creative impulses within me would be akin to gagging a child in a playground.

What is provocative is not always easy to behold and is bound to offend at times. Art tests our boundaries and our limits and artists must be allowed and encouraged to investigate the most unbearable corners of existence because it is only by entering the shadow that we have awareness of

light.

We live within a culture of anxiety, increasingly dominated by a corrosive fear of adverse reaction. Safety and security seem to be worshipped at all costs. It is this unspoken fear of discomfort and unease which kills creativity, whereas tiny moments of faith – a single word, a brush stroke, the germ of an idea – are what help it to flourish.

Every artist has an impetus to tell a story, to impart something. We are explorers and truth tellers. However, in order for what is created to connect with an audience we need the machinery of institutions to support and navigate the work.

Our institutions need to leap in with artists, be brave enough to put on complex work they believe in and then use their imaginations if they have cause to defend it. Surely the best kick in the face for austerity is to encourage artists to take risks and pursue a path of provocation and interrogation.

I hope leaders in the arts can employ dynamism and courage as they fight for freedom of expression and if necessary shout loudly about why it has to be at the core of our cultural fabric in order for the arts in Britain to thrive and be truly diverse.

Let’s not forget that institutions also need support from wider society so it is heartening to know that politicians, lawmakers and the police are finally committing to this conversation and there is the chance to move forward and learn from past mistakes.

Making important artwork isn’t necessarily easy and the end product may not be palatable. But if the work is deemed excellent enough by institutions

to be put on in the first place, then it should not be taken off under any circumstance. Art’s function, after all, is not to maintain the status quo but to change the world. And some people are never going to want that to happen.

Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti is a playwright. Her play Behzti (Dishonour) was cancelled by the Birmingham Repertory Theatre following protests against the play.

Freedom of expression

Freedom of expression is a UK common law right, and a right enshrined and protected in UK law by the Human Rights Act*, which incorporates the

European Convention on Human Rights into UK law.

*(At the time of writing (June 2015), the government is considering abolishing the Human Rights Act and introducing a British Bill of Rights. Free expression rights remain protected by UK common law, but it is unclear to what extent more recent developments in the law based on Article 10 would still apply.)

The most important of the Convention’s protections in this context is Article 10.

| ARTICLE 10, EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers. This article shall not prevent states from requiring the licensing of broadcasting, television or cinema enterprises.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial

integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary. |

It is worth noting that freedom of expression, as outlined in Article 10, is a qualified right, meaning the right must be balanced against other rights.

Where an artistic work presents ideas that are controversial or shocking, the courts have made it clear that freedom of expression protections still apply.

As Sir Stephen Sedley, a former Court of Appeal judge, explained: “Free speech includes not only the inoffensive but the irritating, the contentious, the eccentric, the heretical, the unwelcome and the provocative provided it does not tend to provoke violence. Freedom only to speak inoffensively is not worth having.” (Redmond-Bate v Director of Public Prosecutions, 1999).

Thus to a certain extent, artists and galleries can rely on their right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights: the right to receive and impart opinions, information and ideas, including those which shock, disturb and offend.

As is seen above, freedom of expression is not an absolute right and can be limited by other rights and considerations.

Artists and artistic organisations including galleries, theatres and museums may also draw protection from other protected rights, such as freedom of assembly, which is covered by Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights and in turn the Human Rights Act. Article 11 states:

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of association with others.

2. No restrictions shall be placed on the exercise of these rights other than such as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. This article shall not prevent the imposition of lawful restrictions on the exercise of these rights by members of the armed forces, of the police or of the administration of the State.”

The following sections look at one element area of the law that may be used to have the effect of curtailing free expression: the Public Order Act – the law dealing with issues of public order.

It is worth noting at the outset that artists are rarely charged with public order offences under the act. For an arts organisation it is far more likely that a public order problem arises because of the reactions of third parties to the work of art. For example, a particular group may feel seriously offended, and there may be a risk of violent protest or disorder. Often, protestors may use the threat of potential violence that could result from a provocative work to argue it should be shut down.

Public order law will therefore more often impact artistic works where the police form the view that the reaction it triggers is serious enough to justify closing the work to maintain order. Such a case presents the problem of an otherwise lawful action that causes, results in, provokes or (more neutrally) precedes a breach or threatened breach of the peace, entailing violent action, such that the police require the otherwise lawful act to cease. This will be discussed in greater detail below.

Public order offences explained

The guidance generally applies if you are considering exhibiting or otherwise presenting works that might, after consideration of public response, raise issues of public order.

An artistic performance or exhibition may present material or themes that cause offence to members of the public or members of different social groups. This is by far the most likely way that any public order issue might arise in relation to an artistic work.

Public order law is complicated and its application to any particular case will be fact-specific. It should be borne in mind that much of this area of law – in particular breach of the peace – is governed by the common law. Common law, also referred to as case law, is made by judges and developed in the cases that come before the court over time. This is in contrast to statutory law, which is written law passed by the legislature – the body within government empowered to pass laws. This means that for these areas there is no specific, relevant extract of written legislation.

Two types of laws should be considered when considering potential public order offences:

• Laws that create criminal offences, leading to arrest, prosecution and punishment.

• The powers of the police to deal with a breach of the peace (considered in the next section).

Laws that create criminal offences include:

• The Public Order Act 1986 (POA) http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/64

• Theatres Act 1968 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1968/54

The Public Order Act creates several offences, particularly:

• Riot (Section 1)

• Violent disorder (Section 2)

• Affray (Section 3)

• Fear or provocation of violence (Section 4)

• Intentionally causing harassment, alarm or distress (Section 4a)

• Harassment, alarm or distress (Section 5)

It seems unlikely that Sections 1-4a will apply to most artistic performances. The use of violence in artistic performances is exceptional. It would be rare for an artistic performance to be performed with the intention of provoking violence and most artists, even when dealing with controversial material, would maintain that their intention is not to harass, alarm or distress another person, which would be an offence under Section 4a.

However, where a performance or other form of artistic expression does (exceptionally) involve violent acts, or could be seen as being done with the intent of provoking violence, or of harassing, alarming or distressing a person, then one or more of these provisions may apply. The artist should, in those cases, consider taking the steps explained later in this pack, particularly those that may assist in clarifying the artistic purposes and intentions of a work, as well as taking professional advice.

Section 5 of the Public Order Act differs from the others as it does not require the use or threat of violence, or a specific intention. It applies when a person uses words, behaviour, writings or visual representations that are threatening or abusive, or uses disorderly behaviour, within the hearing or sight of another person who is likely to be alarmed, harassed or distressed. The offence does not apply if the person had no reason to believe that there was any person in sight who could be caused harassment, alarm or distress, or was otherwise acting unreasonably.

Section 5 is therefore broader than the other offences, particularly Section 4a, as it can apply where the person is aware of the potential for their conduct to be threatening or abusive, even without intending this result.

As with the other provisions of the Public Order Act, artists whose work may fall into Section 5 should consider some of the ways of reducing the risk of prosecution discussed elsewhere in this pack. If a person commits an offence against the Public Order Act that is racially or religiously motivated, that person will also commit an offence under race and religious hatred legislation, and be liable to further punishment. This is discussed in detail in the information pack on Race and Religion that forms part of this series of guides.

The Public Order Act itself also has additional rules applying to conduct intending to stir up racial or religious hatred, or hatred on the grounds of sexual orientation.

Parts III and IIIA of the act create offences against writings, plays, recordings or broadcasts where these are intended to stir up racial hatred (in Part III) or religious hatred or hatred on grounds of sexual orientation (Part IIIA).

However, Part IIIA specifically contains protections for free speech where religion is involved. This protection significantly narrows the scope of

Part IIIA.

| PEN AMENDMENT

Section 29J of Part IIIA (the so-called ‘PEN amendment’) states that the rules on public order must not be applied “in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system”. |

The Theatres Act 1968 provides a specific offence in Section 6 of using threatening, abusive or insulting words if these are used with intent to provoke a breach of the peace, or the performance as a whole is likely to occasion a breach of the peace. The concept of a breach of the peace is explained in the following section.

A defence is available where the performance is justified in the “public good”, on the ground that the performance was in the interests of drama, literature or any other kind of art or learning.

The Theatres Act specifically states that a decision to prosecute under Section 6 may also only be taken by the attorney general. The requirement for the attorney general’s permission means that a decision to prosecute is likely to be considered particularly carefully. As the attorney general has a higher profile than an ordinary prosecutor, one would expect his or her decision to be subject to greater public scrutiny.

If arrests have been made by the police, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) will consider whether, based on the evidence supplied by the police, there is a realistic prospect of conviction. This will include whether the work will meet the test of provoking public disorder and whether there is any defence that is likely to succeed. If there is enough evidence, the Crown Prosecution Service will consider whether it is in the public interest to prosecute, taking into consideration the competing rights of the artist, theatre, museum or gallery and others.

The powers of the police and prosecuting authorities

The police have statutory and common law powers to deal with disorder and to prevent anticipated disorder. They can do so by making arrests for various offences, and, importantly, by making arrests or giving directions to persons to prevent a breach of the peace.

In exercising these powers, the police also have duties to give protection to the freedom of speech of all groups and individuals, and any other relevant freedoms, including the right to protest and to manifest a religion. The role of the police naturally shifts with changes in culture and the law. The current position is that the police, as a public authority, have an obligation to ensure law and order and an additional obligation to preserve, and in some cases to promote, fundamental rights such as the right to protest and the right to freedom of expression protected by Articles 10 and 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights, currently incorporated into the UK’s domestic law.

The result is that the police conduct a pragmatic balancing act between the different parties. However, where public order issues arise, the

policing of artistic expression is very much part of the police’s core duties and, as a public body, the police must act within their powers and discharge duties to which they are subject.

At present, there is limited relevant guidance available on the policing of artistic events and therefore policy practice in this area may lack

consistency. This is an area that could potentially be subject to challenge by way of judicial review.

| JUDICIAL REVIEW

Actions by the police and the authorities are subject to review by the courts. Convictions can only be imposed by a court, and may in turn be appealed. Police actions to detain or direct people on the grounds of preventing a breach of the peace may also be reviewed. In general terms, the test on such a review is whether, in light of what the police officer knew at the time, the court is satisfied that it was reasonable to fear an imminent breach of the peace. The information made available to the police by an artistic organisation or artist before an incident may occur is therefore critical to the officer’s, and the court’s, assessment. https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/judicial-review/ |

In addition to laws creating offences, the concept of a breach of the peace also gives the police preventive powers to arrest a person to prevent a

breach of the peace. Causing a breach of the peace is not in itself a crime. However, the police may arrest a person to prevent a breach of the peace, and may require the person to undertake to keep the peace as a condition of release.

BREACH OF THE PEACECourts (not parliament) have defined the concept of a breach of the peace. At its essence, it involves violence or threatened violence, that is:

“whenever harm is actually done or is likely to be done to a person or in his presence to his person, or a person is in fear of being so harmed through an assault, an affray, a riot, unlawful assembly or other disturbance”. A police officer may arrest a person threatening to breach the peace, or give the person directions to prevent a breach, where the breach is imminent.The powers of the police may only be exercised where the breach is in fact imminent. The powers must also be exercised in a manner consistent with human rights protections, including freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Judicial Review proceedings may be brought against the police where their actions contravene these requirements. |