01 May 15 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

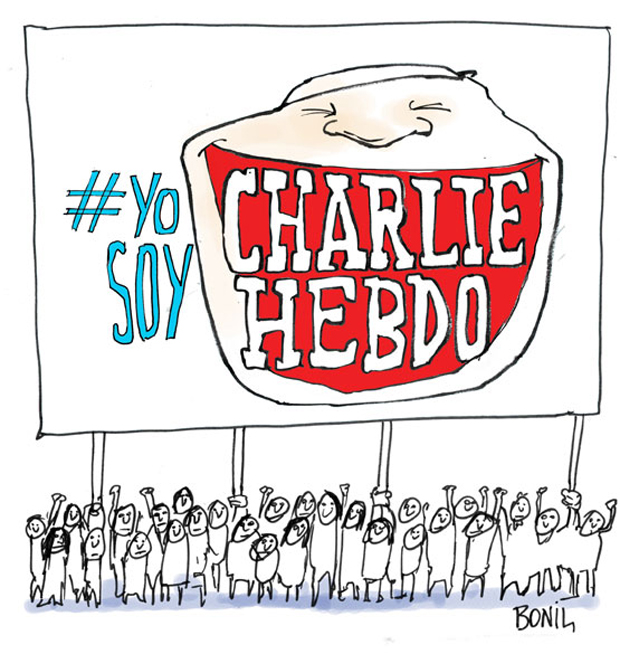

On World Press Freedom Day, 116 days after the attack at the office of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo that left 11 dead and 12 wounded, we, the undersigned, reaffirm our commitment to defending the right to freedom of expression, even when that right is being used to express views that we and others may find difficult, or even offensive.

The Charlie Hebdo attack – a horrific reminder of the violence many journalists around the world face daily in the course of their work – provoked a series of worrying reactions across the globe.

In January, the office of the German daily Hamburger Morgenpost was firebombed following the paper’s publishing of several Charlie Hebdo images. In Turkey, journalists reported receiving death threats following their re-publishing of images taken from Charlie Hebdo. In February, a gunman apparently inspired by the attack in Paris, opened fire at a free expression event in Copenhagen; his target was a controversial Swedish cartoonist who had depicted the prophet Muhammad in his drawings.

A Turkish court blocked web pages that had carried images of Charlie Hebdo’s front cover; Russia’s communications watchdog warned six media outlets that publishing religious-themed cartoons “could be viewed as a violation of the laws on mass media and extremism”; Egypt’s president Abdel Fatah al-Sisi empowered the prime minister to ban any foreign publication deemed offensive to religion; the editor of the Kenyan newspaper The Star was summoned by the government’s media council, asked to explain his “unprofessional conduct” in publishing images of Charlie Hebdo, and his newspaper had to issue a public apology; Senegal banned Charlie Hebdo and other publications that re-printed its images; in India, Mumbai police used laws covering threats to public order and offensive content to block access to websites carrying Charlie Hebdo images. This list is far from exhaustive.

Perhaps the most long-reaching threats to freedom of expression have come from governments ostensibly motivated by security concerns. Following the attack on Charlie Hebdo, 11 interior ministers from European Union countries, including France, Britain and Germany, issued a statement in which they called on internet service providers to identify and remove online content “that aims to incite hatred and terror”. In the UK, despite the already gross intrusion of the British intelligence services into private data, Prime Minister David Cameron suggested that the country should go a step further and ban internet services that did not give the government the ability to monitor all encrypted chats and calls.

This kind of governmental response is chilling because a particularly insidious threat to our right to free expression is self-censorship. In order to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, individuals must be able to communicate without fear of intrusion by the state. Under international law, the right to freedom of expression also protects speech that some may find shocking, offensive or disturbing. Importantly, the right to freedom of expression means that those who feel offended also have the right to challenge others through free debate and open discussion, or through peaceful protest.

On World Press Freedom Day, we, the undersigned, call on all governments to:

• Uphold their international obligations to protect the rights of freedom of expression and information for all, especially journalists, writers, artists and human rights defenders to publish, write and speak freely;

• Promote a safe and enabling environment for those who exercise their right to freedom of expression, especially for journalists, artists and human rights defenders to perform their work without interference;

• Combat impunity for threats and violations aimed at journalists and others threatened for exercising their right to freedom of expression and ensure impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations that bring masterminds behind attacks on journalists to justice, and ensure victims and their families have speedy access to appropriate remedies;

• Repeal legislation which restricts the right to legitimate freedom of expression, especially such as vague and overbroad national security, sedition, blasphemy and criminal defamation laws and other legislation used to imprison, harass and silence journalists and others exercising free expression;

• Promote voluntary self-regulation mechanisms, completely independent of governments, for print media;

• Ensure that the respect of human rights is at the heart of communication surveillance policy. Laws and legal standards governing communication surveillance must therefore be updated, strengthened and brought under legislative and judicial control. Any interference can only be justified if it is clearly defined by law, pursues a legitimate aim and is strictly necessary to the aim pursued.

PEN International

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre

Albanian Media Institute

Article19

Association of European Journalists

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Belarusian PEN

Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

Cambodian Center for Human Rights

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility

Centre for Independent Journalism – Malaysia

Danish PEN

Derechos Digitales

Egyptian Organization for Human Rights

English PEN

Ethical Journalism Initiative

Finnish PEN

Foro de Periodismo Argentino

Fundamedios – Andean Foundation for Media Observation and Study

Globe International Center

Guardian News Media Limited

Icelandic PEN

Index on Censorship

Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information

International Federation of Journalists

International Press Institute

International Publishers Association

Malawi PEN

Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

Media Institute of Southern Africa

Media Rights Agenda

Media Watch

Mexico PEN

Norwegian PEN

Observatorio Latinoamericano para la Libertad de Expresión – OLA

Pacific Islands News Association

PEN Afrikaans

PEN American Center

PEN Catalan

PEN Lithuania

PEN Quebec

Russian PEN

San Miguel Allende PEN

PEN South Africa

Southeast Asian Press Alliance

Swedish PEN

Turkish PEN

Wales PEN Cymru

West African Journalists Association

World Press Freedom Committee

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

01 May 15 | Denmark, European Union, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Macedonia, mobile, News and features, Poland, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom

As we approach World Press Freedom Day, the right to freedom of expression will again be celebrated as an inalienable European value across the continent — by the public, the media and politicians alike. But to many, this will mean little more than engaging in a well trodden mental routine. We hardly consider the difficulties that freedom of expression faces in practice.

In the first part of 2015, more than a third of journalist killings in the word took place in two European countries; France and Ukraine. If it is true that Europe’s reactions to the Charlie Hebdo attack — the majority of them very emotional — were salubrious, they simultaneously gave rise to ambiguous situations. Many of the leaders that will on 3 May reaffirm their commitment free expression, supported the same message by taking part in the historic march in Paris on 11 January.

But upon seeing Angela Merkel, some were also reminded that Germany continues to treat blasphemy as a crime — as do Denmark, Spain, Poland and Greece, among others. Ireland, whose Enda Kenny was also in attendance, has a constitution which specifically mentions blasphemy and in 2010 enacted a new law against it. All these European countries defend themselves by saying that they do not apply their laws against “blasphemers”. That argument does not carry much weight when it comes to opposing those countries — Saudi Arabia, Iran, various Asian countries — that have tried to turn blasphemy into a universal crime recognised by the UN.

Spain’s Mariano Rajoy too marched in solidarity, but his government has taken steps to promote changes in the penal code that would “represent a serious threat to freedom of information, expression and the press”.

And what was Viktor Orban doing in Paris? The Hungarian president has reunified Hungary‘s public media so as to better bind them to his own party. Despite being the leader of an EU country, Orban has followed Vladimir Putin’s example. In this experimental model, the Andrei Sakharov Center and Museum is no longer ordered to close as it was in the old days, but rather fined 300,000 roubles (€5,000) for failing to register as a “foreign agent”. One day brings an announcement of compulsory registration for bloggers in Russia; another day, harassment against Russian and Hungarian NGOs perceived as “unpatriotic”.

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutohlu traveled to Paris, only to later label Charlie Hebdo’s post-attack issue a “provocation”. A reminder: Turkey is an EU candidate country where dozens of journalists have been sentenced to prison, and where various internet sites, including those that dared to reproduce some of Charlie Hebdo’s caricatures, have been blocked.

But also present at the march, were various representatives of European journalists — myself included. Just behind the Charlie Hebdo survivors, we carried a banner with the message “Nous sommes Charlie”.

Walking next to me was Franco Siddi, of the Italian National Press Federation. He talked to me about how imprisonment for defamation is still a possibility in Italy, though the European Court of Human Rights has ruled it a disproportionate punishment.

In my home country Spain too, this possibility of imprisonment remains, even if under Spanish jurisprudence freedom of expression consistently prevails over the demands of plaintiffs. In Italy, the situation is the same, yet my Italian colleagues point out that in 2014 alone, 462 journalists in the country were threatened with legal action for alleged acts of defamation. And while the current proposal for reform being considered foresees eliminating the possibility of jail time, it increases the potential fines.

This is not the only potential legal threat facing European journalists. Long before 9/11, there existed a reflexive habit of passing “urgent” laws under security pretexts, as in the UK during the most difficult years of the Northern Ireland conflict. The current model is the United States’ Patriot Act, which has recently been discussed in France. Meanwhile, in Britain and Spain are debating what free expression activists describe as “gag laws”. In Macedonia, the sentencing of the investigative journalist Tomislav Kezarovski to two years in prison under one of these security inspired laws stands out as a warning sign.

Against this worrying backdrop, across Europe journalists, freedom advocates, campaigners and even politicians are standing up for press freedom. When Gvozden Srecko Flego, member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, recently highlighted the cases of Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and Azerbaijan as particularly problematic, he also suggested a countermeasure. He recommends “organising annual debates […], with the participation of journalists’ organisations and media outlets” in the respective parliaments of each state.

Media concentration, one of the most serious challenges to media pluralism and free expression in Europe, is being tackled. One proposal, which some international bodies have already accepted, would create a “Media Identity Card” requiring owners to publicly identify themselves and thus create an environment of more open and transparent media ownership.

When defending freedom of expression as a European value, we cannot allow ourselves to simply fall in into mental routines. This World Press Freedom Day we need both words and actions.

Paco Audije is a member of the Steering Committee of the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This column was posted on 1 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Apr 15 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

What if your job, your career, was winding up an entire nation?

That’s it. Sure, you have a column in a national newspaper. But what can you really do with it? You can’t really share your thoughts on the common toad, or tell delightful stories about your children misunderstanding foreign words, much less offer some insight into the workings of the modern world. Sure, you can chuck the odd piece of light relief in the sidebar or the basement, but that’s not what people are here for. We’ve come to your column to be thrilled by your outrageous views, and thrilled we will be.

Last time round it was people giving food to, and receiving food from, charity.

“SAY the words food bank” La Dolce ‘Opkina began, “and I am supposed to put on my concerned face and proffer up a can of beans.”

Where’s this going Katie? Where could this possibly be going?

“But all I’ve found in the back of my cupboard is two fingers. And they don’t belong to a Kit Kat.”

BOOM! Gotcha. I mean, it makes no sense. If it’s the fingers at the end of her arm she’s using, why are they in the back of the cupboard? Unless, maybe, she is SO outrageous that she keeps a special V-flipping apparatus in her cupboard, as her doctor has advised her that the constant extension and retraction of her index and middle finger was putting her in serious risk of chronic RSI. But then, if you were using it that much, you wouldn’t keep it in the back of the cupboard. You’d have it on the hall table, perhaps. Or in a little belt-mounted pouch, like a techie’s mobile phone, ready to unleash, cosh-style, upon passing do-gooders, bed-wetters, namby-pambies, oiks, poshos, hippies, liberal elitists, ignorant yokels, EUROCRATS, trendy vicars, Trots, gypsies, useless husbands, trashy wives, “gay rights” activists, lesbo-feminists and everyone else you might bump into at a reasonably-sized community festival in a reasonably-sized town.

It must be exhausting keeping track of this roll call of resentment. It must be wearing to have to be angry every week. How draining to have a public persona dedicated to hating everything and everyone.

And then there is the fact that outrage is a substance which can be addictive, but to which people can also develop a considerable tolerance. In order to keep us interested — and quite possibly to keep herself interested also — Hopkins has to keep upping the dose, until eventually we get to the point where she’s describing poor African people drowning in the sea as cockroaches and everyone suddenly stops and thinks “oh”.

The problem the serial controversialist who has nothing else to trade on faces is that the only way to go is down. The very nature of the job and the stuff you are peddling means you must, inevitably, end up overstepping the mark. In the case of Jeremy Clarkson, a carnival of boorishness ended in violence, where it had to. Hopkins seems to have survived, but she’s Zugzwanged herself: tone down the schtick and she becomes pointless; the only other move available is directly into the abyss. This is the fate of the wind-up merchant.

The exception to this rule is the satirist. The essential difference between the satirist and the controversialist is that the controversialist puts herself forward, from the beginning, as the stoic truthteller, striving alone in a world gone mad. Controversialists tend to be declinists: the world is steadily getting worse. The converse of this is the belief that at some point, usually in the period of the controversialist’s late adolescence, the world was right.

Satirists hold out no such (perverse) hope. The world is awful, the world has always been awful, and the only way to get through it is to laugh and hope we can make some tweaks around the edges. It is curious then, that from Private Eye to Charlie Hebdo, satire is often linked to campaigning journalism in the same publication.

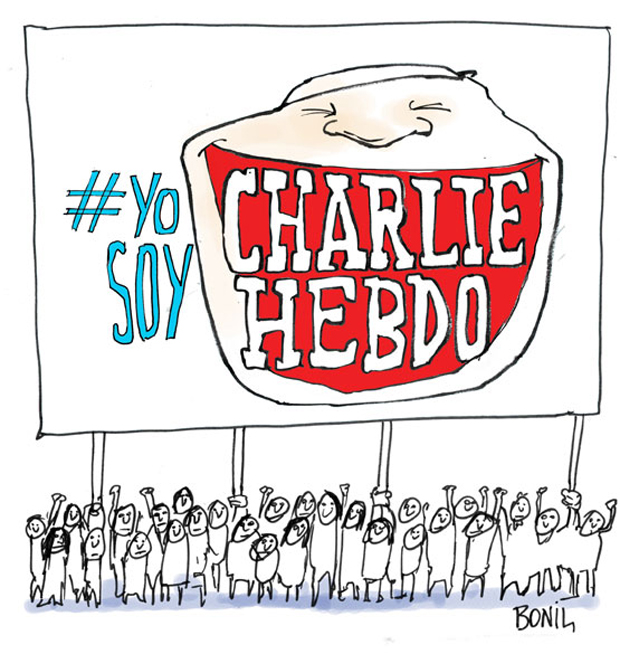

Charlie has once again been in the news after several US-based authors refused to take part in a gala in honour of the magazine hosted by PEN American Center.

The writers’ heckles were raised by what they saw as racist cartoons run by Charlie in the past. Among these were one of a black politician portrayed as a monkey, and Nigeria girl victims of Boko Haram portrayed as “welfare queens”. Of course, at face value, these seem racist (though it is worth noting that it was not racist cartoons that saw Charlie’s staff slain: it was cartoons that refused to obey religious taboo).

What the US critics failed to acknowledge was that all satire is reactive: the cartoons did not simply spring unprompted from the cartoonists’ pens. The case of the ape cartoon was a reaction to far right portrayals of the minister, and the accompanying text very clearly mocked the Front National’s leader Marine Le Pen. As Irish novelist and Charlie columnist Robert McLiam Wilson pointed out:

“Without the snipped-off text underneath, and the knowledge of the lamentable tosh it was lampooning, of course Charlie would seem racist. It would seem racist to me too. But to strip the image of its fundamental components like this is akin to saying the incomparable Jonathan Swift was a baby-eating Nazi and that A Modest Proposal was actually a cookbook.”

Satire must toy with what it sets out to mock: otherwise it is meaningless and unintelligible. Sometimes the controversy of the likes of Hopkins and the irony of Charlie can look, at first glance, identical.

And sometimes not: While Hopkins was describing “cockroaches” drowning in the Mediterranean, Charlie was echoing the refrain of many: “A Titanic every week,” with a cartoon depicting a white woman singing My Heart Will Go On while a despairing migrant begs her to “shut up” (Ta Guelle).

Bracing? Sure. But humanising, too. As satire should be and controversialism never is.

This column was posted on 30 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

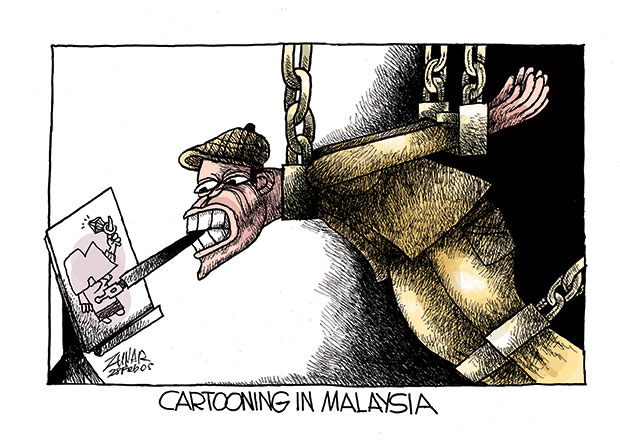

29 Apr 15 | Events, mobile

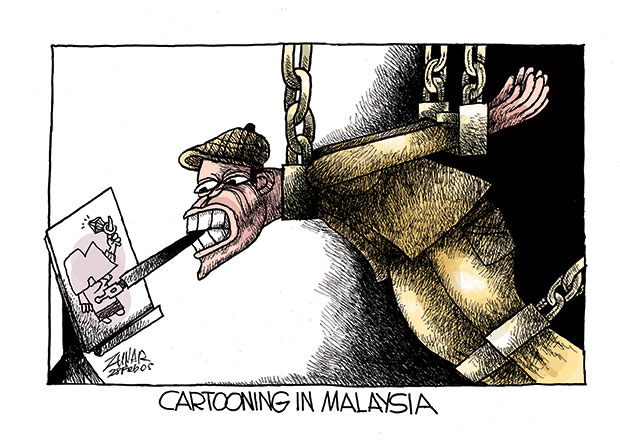

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar is currently facing 9 charges under the country’s sedition act, with a maximum penalty of 43 years imprisonment. Five of his books have already been banned, containing cartoons deemed “detrimental to public order”. Since 2009, his Kuala Lumpur office has repeatedly been raided, thousands of his cartoons confiscated and publishers and bookstores warned off printing or carrying any of his titles.

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar is currently facing 9 charges under the country’s sedition act, with a maximum penalty of 43 years imprisonment. Five of his books have already been banned, containing cartoons deemed “detrimental to public order”. Since 2009, his Kuala Lumpur office has repeatedly been raided, thousands of his cartoons confiscated and publishers and bookstores warned off printing or carrying any of his titles.

In a year when cartoons have rarely been far from the headlines, join us for an evening with an award-winning satirist who says “I will keep drawing until the last drop of my ink”.

One week before his trial in Malaysia, Zunar will be joined by political cartoonist Martin Rowson to share his story through words and pictures.

Where: Free Word Centre, London

When: Thursday 14 May 2015, 7.30pm

Tickets: Limited, booking essential – Book here

Related: Drawing pressure: Cartoons from around the world

Presented in partnership with Article 19 and supported by Free Word

29 Apr 15 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features

OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović, at the Permanent Council in Vienna, 16 January 2014. (Photo: OSCE)

Anniversaries and commemorations are times to reflect, judge and move forward. So it is with World Press Freedom Day, which we note for the 22nd time this year amid worldwide evidence of hostility toward the media.

The date of 3 May was set aside by the UN General Assembly in 1993 to foster free, independent, pluralistic media worldwide.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the largest regional security organisation in the world, just four years later in 1997 created the position I now hold, the Representative on Freedom of the Media. The position was established expressly to help countries that are members of the organisation (which includes all of Europe, the countries of the former Soviet Union and Mongolia, as well as the United States and Canada) implement their promises to uphold the rights to free expression and free media.

It is my job to advocate for these two concepts. It is also my job to help, cajole and sometimes plead with the 57 nations in the organisation to simply live up to their promises to provide the environment in which free expression and free media can flourish.

Over the past 18 years only three people have held the position of Representative. As I enter my sixth and last year in this position, the time has come to reflect on the state of media freedom and to analyse the overall health of free expression across the OSCE region.

To do so, I needed a base from which to judge. I found that by returning to the very first public statement issued by the Representative’s office, then headed by German politician Freimut Duve, on 7 September 1998. It announced, ironically, that Duve had been denied a visa by authorities in Belgrade to visit the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, to lobby the government to change its policy of denying visas to reporters from other countries, some of whom were considered foreign intelligence agents.

The Helsinki Final Act of 1975, the very document that eventually brought the OSCE into existence, expressly called for improving the working conditions for journalists, which included examining “in a favorable spirit and within a suitable and reasonable time scale requests from journalists for visas” and to “grant to permanently accredited journalists…on the basis of arrangements, multiple entry and exit visas for specified periods”.

Duve wrote in the public statement: “Tito himself, as President of the former Yugoslavia, signed in 1975 his country’s acceptance of the principles and commitments of the Conference for Security and Cooperation in Europe.”

Those commitments expressly included the right of journalists to work internationally.

Promises made. Promises not kept.

Have things changed over the years?

The fact that you are reading this posting identifies you as someone well aware of the precarious position journalists and the media find themselves in today. They face a litany of problems, none of which is bigger than the issue of life itself.

The year 2015 hardly had started when eight journalists for the French magazine Charlie Hebdo were murdered in their office in Paris – over the depiction of a religious figure. Two weeks later, a discussion group in Copenhagen convened to talk about the Paris incident came under gunfire with another person killed. So much for free media. So much for free expression.

But we all know that while homicidal violence against journalists is the most drastic form of attack on free media, it is not the only one. Across the OSCE region media is subject to all nature of offences: criminal defamation laws that put reporters in jail for rooting out corruption in public places; cyber-attacks that plague internet media sites; new laws that are being adopted to criminalise free expression in the name of fighting terrorism; and increasing regulation of the internet in an effort by authoritarian governments to squelch media and free expression advocates.

The simple violations of media rights continue, too. In the past 12 months I have written to authorities and issued public statement on at least six occasions condemning the refusal of governments in the OSCE region to grant visas to foreign-based reporters. Have things really changed in 2015 from 1998? Only the countries involved; not the practices.

But even if my judgment on the past 18 years is harsh, media freedom advocates, such as me, must continue to move forward and provide the defenses necessary for free expression and free media to flourish. Complacency is not an option.

Solidarity, however, is.

For example, three rapporteurs on free expression from the United Nations, the Organization of American States and the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights and I annually issue a joint declaration on a topic related to free expression. Those declarations now are seeing their way into decisions of national and international bodies, including judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. This is real progress. Decisions upholding citizens’ rights under Article 10 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms are real results.

And all of us must continue to raise the issue of the rights of media before national legislatures. Public awareness campaigns on behalf of media can be effective tools to prod elected officials to spend the resources, including political capital, necessary to build environments conducive to free expression. Elected officials and their appointed, often nameless and faceless bureaucrats, can be taught and encouraged to write good laws and appoint good law enforcement authorities, including police, prosecutors and judges, to interpret those laws in a fashion that will provide oxygen for those who champion free expression.

It is easy to become disillusioned and depressed by the daily fare of media issues. We should recognise the perilous state of free media and free expression in many spots in the world. But we never should lose our focus. We should take note of this date and make a personal commitment to stand for the basic human rights of free expression and free media – this year and the next and the years after that.

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This column was posted on 29 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Apr 15 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, mobile

Editorial cartoon on the Baku European Games From Meydan TV (Image: Meydan TV)

In six weeks, the inaugural European Olympic Committee (EOC)-backed European Games will start in Azerbaijan’s capital Baku. Meanwhile, concerns about the human rights situation in the country are mounting. The latest chapter in the ongoing crackdown on government critics saw pro-democracy activist Rasul Jafarov and human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev sentenced to 6.5 and 7.5 years in prison, respectively.

Against this backdrop, Index on Censorship, Human Rights Watch and Article 19 on 28 April hosted Give Human Rights a Sporting Chance in Azerbaijan at the Frontline Club in London. The event addressed the question of how journalists can effectively cover the games given the full scope of social and political issues in Azerbaijan.

From left: Emin Milli, Rebecca Vincent and Giorgi Gogia speaking speaking on the crackdown on government critics in Azerbaijan ahead of this summer’s Baku European Games (Photo: Index on Censorship)

On the panel were Emin Milli, a former political prisoner in Azerbaijan, now director of Meydan TV; Rebecca Vincent, coordinator of the Sport for Rights campaign; and Giorgi Gogia, Human Rights Watch’s senior researcher on Azerbaijan who was recently denied entry into the country. These were some of their key points:

1) Azerbaijan’s human rights community has been all but wiped out over the past year

2) In light of the human rights situation in Azerbaijan, the EOC is not free of responsibility…

3) …and neither are European states

4) The Azerbaijani government has invested in an international PR campaign — and it’s working

5) The games are not popular among ordinary Azerbaijanis

6) Sports journalists should report on more than just sports during the games

7) Despite Azerbaijan’s current climate, human rights activism remains important and worthwhile

This article was posted on 29 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

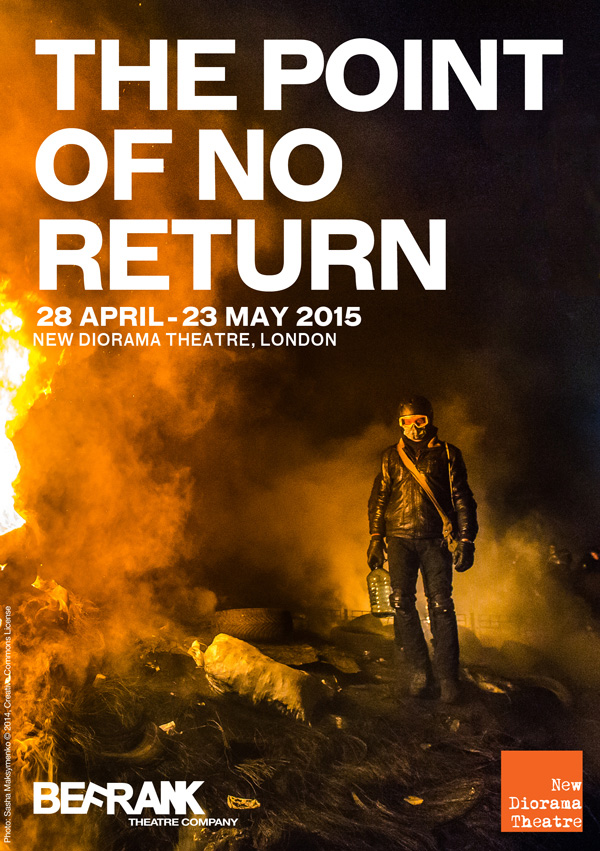

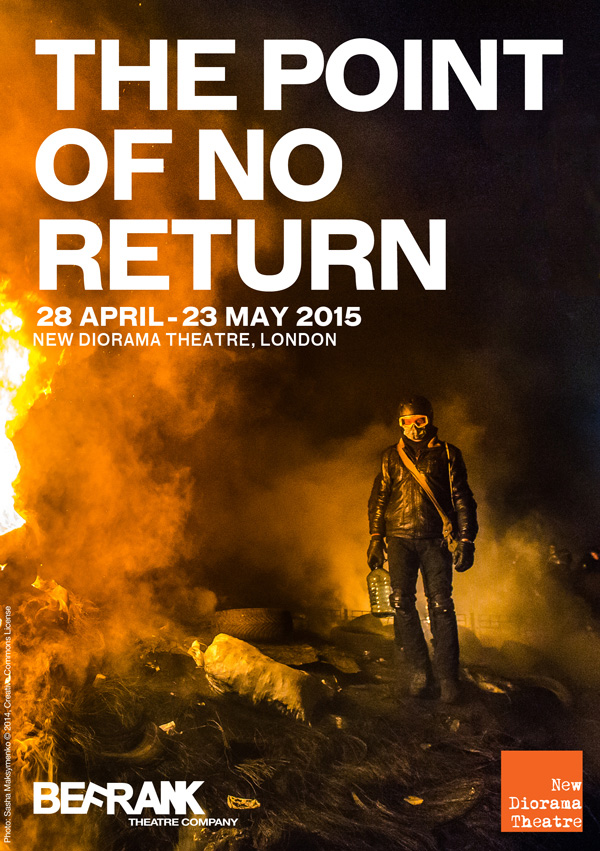

28 Apr 15 | Events, mobile

The Point of No Return, a new play based upon the last four days of Ukraine’s Maidan protests. From personally recorded real-life stories, extensive research and a journey to the heart of Ukraine, this story is based upon the revolution in Kiev in January-February 2014.

The performance on 6 May will be followed by a discussion including Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship:

- How important is freedom of speech to democracy?

- What form did censorship take in the Ukrainian revolution?

- How is censorship happening in the UK today?

Index joins BeFrank Theatre Company for an evening of debate and discussion about the future of free speech in the UK, Ukraine and across the world.

Where: New Diorama Theatre, London (Nearest Tube: Warren St)

When: Wednesday 6 May 2015, 7.30pm

Tickets: £12-£15 / Book here

An earlier version of this event provided the wrong date. It takes place on 6 May.

28 Apr 15 | Campaigns, Events, mobile

Razan Zaitouneh, above, Samira Khalil, Nazem Hamadi and Wa’el Hamada were abducted on 9 December 2013

To mark the 38th birthday (on April 29) of missing human rights defender and lawyer Razan Zaitouneh, head of the Violations Documentation Centre in Syria (VDC), winner of the 2011 Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought and the 2011 Anna Politkovskaya Award of RAW in WAR (Reach All Women In War), the undersigned human rights organizations today reiterate their call for her immediate release, as well as that of her missing colleagues Samira Khalil, Nazem Hamadi and Wa’el Hamada.

On December 9, 2013, the four human rights defenders, collectively known as the “Duma Four”, were abducted during a raid by a group of armed men on the offices of the VDC in Duma, near Damascus. There has been no news of their whereabouts or health since.

The VDC is active in monitoring and reporting on human rights violations in Syria and the undersigned organizations believe that the abduction of the four activists was a direct result of their peaceful human rights work. Their ongoing detention forms part of a wider pattern of threats and harassment by both government forces and non-state actors seeking to prevent human rights defenders exposing abuses.

In the months prior to her abduction Razan Zaitouneh wrote about threats she had been receiving and informed human rights activists outside Syria that they originated from local armed groups in Duma. The most powerful armed group operating in Duma at the time of the abductions is the Army of Islam headed by Zahran Alloush. In April 2014, Razan Zaitouneh’s family issued a statement saying they held Zahran Alloush responsible for her and her colleagues’ wellbeing given the large presence his group maintained in the area.

The undersigned organizations, as well as other activists, have been calling for the release of the “Duma Four” since their abductions. Today they again urge the Army of Islam and other armed groups operating in the area to take immediate steps to release the abducted VDC staff, or investigate their abduction and work for their release. They further urge governments that support these groups, as well as religious leaders and others who may have influence over them, to press for such action, in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 2139, which “strongly condemns” the abduction of civilians and demands and immediate end to this practice.

Razan Zaitouneh has been one of the key lawyers defending political prisoners in Syria since 2001. She has played a key role in efforts to defend the universality of human rights and support independent groups and activists in Syria. Along with a number of other activists, she established the VDC and co-founded the Local Coordination Committees (LCCs), which co-ordinate the work of local committees in various cities and towns across Syria. She also established the Local Development and Small Projects Support Office, which assists non-governmental organizations in besieged Eastern Ghouta.

Samira Khalil has been a long-time political activist in Syria and had been detained on several occasions by the Syrian authorities as a result of her peaceful activism. Before her abduction, she was working to help women in Duma support themselves by initiating small income-generating projects. Wa’el Hamada, an active member of the VDC and co-founder of the LCC network had also been detained by the Syrian authorities. Before his abduction he was working, together with Nazim Hamadi, to provide humanitarian assistance to the residents of besieged Eastern Ghouta.

Signatories:

Alkarama Foundation

Amman Center for Human Rights Studies

Amnesty International

Arab Foundation for Development and Citizenship

Arab Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

Arab Organization for Human Rights in Syria

Badael Foundation

Bahrain Centre for Human Right

Defending prisoners of conscience in Syria Organization

Cairo Center for Development (CCD)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

Centre for Democracy and Civil Rights in Syria

Committees for the Defending Democratic Freedoms and Human Rights in Syria

El-Nadeem Center for Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence

Enmaa Center for Democracy and Human Rights

Fraternity Center for Democracy and civil society

Front Line Defenders (FLDs)

Freedom House

Gulf Center for Human Rights

Human Rights Fist Society , Saudi Arabia

Human Rights Organization in Syria – MAF

Human Rights watch (HRW)

Humanist Institute for Co-operation with Developing Countries (HIVOS)

Hand in Hand Organization , Syria

Monitor for Human Rights in Saudi Arabia

Index on Censorship

International Media Support (IMS)

International Centre for Supporting Rights and Freedoms

International Civil Society Action Network (ICAN)

International Service For Human Rights (ISHR)

The Tunisian Initiative for Freedom of Expression

Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR)

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) under the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Iraqi Women Network

Iraqi Journalists Rights Defense Association(IJRDA)

Iraqi Network for social Media

Kurdish Committee for Human Rights in Syria (observer)

Kurdish Organization for Human Rights in Syria (DAD)

Kvinna till Kvinna Foundation

Lawyers for Lawyers

Lulua Center for Human Rights

Madad NGOs

Maharat Foundation

MENA Media Monitoring group

Metro Centre to Defend Journalists in Iraqi Kurdistan

National Organization for Human Rights in Syria

Nazra for Feminist Studies

No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ)

One World Foundation (OWF)

Omani Observatory for Human Rights

World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) under the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Pax for Peace – Netherland

Pen International

Reach All Women in War (RAW)

Reporters Without Boarders (RSF)

Sentiel Human Rights Defenders

Syrian American Council (SAC)

Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM)

Syrian Center for Legal Researches & Studies

Syrian Journalists Association

Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR)

Syrian League for Citizenship

Violations Documentation Center in Syria (VDC)

Yemeni organization for defending human rights and democratic freedom

28 Apr 15 | Counter Terrorism, Digital Freedom, Germany, mobile, News and features, United Kingdom, United States

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

Wrestling with his fear about Googling the composition of a carbon dioxide bomb after hearing of a failed bombing at LAX, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung journalist, Peter Galison highlights one of the threats of mass surveillance to journalistic practice, “The knowledge that I might be walking into a security word search had been enough to make me hesitate.”

Following Edward Snowden’s leaks outlining the capabilities of intelligence agencies around the world to monitor, track and collate private online communications this moment of hesitation before tackling a story has become a major concern to journalists globally.

Pen International surveyed 772 fiction and non-fiction writers and found out that more than 1 in 3 writers in so-called free countries (34%) said they had avoided writing or speaking on a particular topic following the NSA revelations.

While Ryan Gallagher of The Intercept states “self-censorship is never the only available option” he acknowledges that his practices have changed:

“In the post-Snowden environment I definitely use encryption tools much more to communicate with people, mainly because more of my colleagues and contacts have now adopted these tools. It’s no longer a niche thing…the Snowden revelations were a big wake-up call for people.”

Encryption and anonymity software have emerged as the primary set of tools available to journalists to protect themselves, their stories and their sources. Indeed in the light of the leaked information, they have taken on added significance; the ability to depend on robust communication security may be the difference between coverage and self-censorship.

Jillian York, director for international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation outlines this central anxiety: “I’ve spoken to journalists who, upon realizing the extent of the NSA’s surveillance, have changed their practices. Some have adopted encryption…while others say they are afraid to cover certain topics.”

This tension between technical literacy and forms of self-censorship defines journalism in the mass surveillance age. As Cyrus Farivar of Ars Technica writes: “less tech-literate journalists may not even be aware of the threats that they may or may not face”.

The advent of blogging and social media, as well as the increase of citizen journalism around the world has enabled a diverse range of voices to join the debate around key issues but as Chris Frost, the chair of the ethics council at the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) states, this can expose many more people to the threat of mass surveillance: “Freelance journalists, citizen journalists and bloggers would need to be sure that they have the technical know-how to safeguard their sources and understand the potential risks involved.”

Are key issues being avoided by those unable to guarantee total security in their communications? And if this is the case, what voices are being silenced?

This is not a threat for journalists alone. For Chris Frost and the NUJ, security and anonymity for sources is paramount: “Without the protection of sources, some people will refuse to speak to the media, for fear of being exposed.” As Ryan Gallagher says: “Quite simply, we don’t have a choice. We must protect our sources and we can’t do that if we don’t change the way we operate online.”

The ability of journalists to protect information from the state is also a vital step in protecting themselves when reporting in conflict zones. As Chris Frost writes, “if journalists are perceived as informers to the authorities, or as future witnesses in a trial, they can become a target.” Mass surveillance is a central tool for states to acquire and share information with its intelligence partners around the world. Implicating journalists as the source of the leak further endangers their safety and therefore their willingness to cover certain issues, as Ryan Gallagher articulates: “Some people may find it too daunting and just steer clear.”

The first principle on the International Federation of Journalists’ Declaration of Principles is “Respect for truth and for the right of the public to truth is the first duty of the journalist”, and this highlights the divergent interests of the state and the media. Where truth is withheld by the state, often in the name of “national security”, the role and responsibilities of journalists in informing the public is brought to the fore. Mass surveillance technologies are powerful tools for states to hinder and restrict this process, manipulating the media landscape to benefit their own aims and objectives at the expense of an informed and engaged civil society.

How journalists learn to navigate this landscape will determine their continued willingness and ability to report on sensitive issues, defending journalism in the public interest across the globe.

But, as Ryan Gallagher reminds us, this willingness is not easily defeated: “Thankfully there are a lot of courageous reporters in the world who will work to get out important information to the public no matter what. So fear will never be completely effective at shutting down media coverage.”

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This article was posted on 28 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Apr 15 | Campaigns, France, mobile, News and features, Statements, United Kingdom, United States

The decision by six authors to withdraw from a PEN American Center gala in which Charlie Hebdo will be honoured with an award once again emphasises the dangerous notion that some forms of free expression are more worthy than others of defending.

Charlie Hebdo was offensive to many — but as PEN points out — it was also vigorous in its defence of the importance of free speech, even in the face of those who would seek to silence that view through violence.

“Free speech for all can only be protected by standing up as vigorously – if not more vigorously – for the views you disagree with as those with which you agree,” said Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “If we don’t do that, freedom becomes something only for the favoured and powerful.”

Below Index republishes an article from CEO Jodie Ginsberg written a week after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo that addresses the importance of a defence of free speech in all its forms.

If you said “I believe in free expression, but…” at any point in the past week, then this is for you. If you declared yourself to be “Charlie”, but have ever called for an offensive image to be removed from public viewing, then this is for you. If you “liked” a post this week affirming the importance of free speech, but have ever signed a petition calling for a speaker to be banned, then this is for you.

Because the rush to affirm our belief in free expression in the wake of Charlie Hebdo attacks ignores a simple truth: that free speech is being eroded on all sides, and all sides are responsible. And it needs to stop.

Genuine free expression means being able to articulate thoughts, feelings and ideas without fear of harm. It is vital because without it individuals would be subject to the whim of whichever authority dictated what ideas and opinions – as opposed to actions – are acceptable. And that is always subjective. You need only look at the world leaders at Sunday’s Paris solidarity march to understand that. Attendees included Ali Bongo, President of Gabon, where the government restricts any journalism critical of the authorities; Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, whose country imprisons more journalists in the world than any other; and the UK’s David Cameron, who declared his support for free expression and the right to offend, while his government considers laws that could drive debate about extremism underground.

It is precisely the freedom for others to say what you may find offensive that protects your own right to express your views: to declare, say, your belief in a God whom others deny exists; or to support a political system that others dismiss. It is what enables scientific and academic thought to progess. As soon as we put qualifications around “acceptable” free expression, we erode its value. Yet that is precisely what happened time and again in response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks, with individuals simultaneously declaring their support for free expression while seeming to suggest that the cartoonists and anyone else who deliberately courts offence should choose other ways to express themselves – suggesting that the responsibility for “better” speech always lies with the person deemed to be causing offence rather than the offended.

“The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write and print with freedom…”

French National Assembly, Declaration of the Rights of Man, August 26, 1789

Index believes that the best way to tackle speech with which you disagree, including the offensive, and the hateful, is through more speech, not less. It is not through laws and petitions that restrict the rights of others to speak. Yet, increasingly, we use our own free speech to call for that of others to be limited: for a misogynist UK comedian to be banned from our screens, or for a UK TV personality to be prosecuted by police for tweeting offensive jokes about ebola, or for a former secretary of state to be prevented from giving an address.

A project mapping media freedom in Europe, launched by Index just over six months ago, shows how journalists are increasingly targeted in this region, including – prior to last week’s incidents – 61 violent attacks against the media. Globally, the space for free expression is shrinking. We need to reverse this trend.

If you genuinely believe in the value of free speech – that all ideas and opinions must be heard – then that necessarily extends to the offensive and the vile. You don’t have to agree with someone, or condone what they are saying, or the manner in which it is said, but you do need to allow them to say it. The American Civil Liberties Union got this right in 1978 when they defended the rights of a pro-Nazi group to march in Chicago, arguing that rights to free expression needed apply to all if they were to apply to any. (As did charity EXIT-Germany late last year, when it raised money for an anti-fascism cause by donating money for every metre walked during a neo-Nazi march).

Countering offensive speech is – of course – only possible if you have the means to do so. Many have observed, rightly, that marginalisation and exclusion from mainstream media denies many people the voice that we would so vociferously defend for a free press. That is a valid argument. But this should be addressed – and must be addressed – by tackling this lack of access, not by shutting down the speech of those deemed to wield power and privilege.

Voltaire has been quoted endlessly in support of free expression, and the right to agree to disagree, but British author Neil Gaiman, who discusses satire and offence in the winter Index magazine, also had it right. “If you accept — and I do — that freedom of speech is important,” he once wrote, “then you are going to have to defend the indefensible. That means you are going to be defending the right of people to read, or to write, or to say, what you don’t say or like or want said…. Because if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

This article was originally posted on 12 January 2015 and reposted on 27 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Apr 15 | Bosnia, mobile, News and features

Sara, Nataša, Elma and Lejla (clockwise, from top left) are local correspondents for Balkan Diskurs.

At first glance it’s easy to mistake Bosnia and Herzegovina’s media landscape as one of promise. With a constitution that guarantees freedom of the press, a large number of media outlets, and a financially independent regulatory body, the small Balkan country performs relatively well by Southeast European standards.

But on closer inspection such freedoms are a mere façade, hiding this divided, post-war state’s continued struggle with a highly polarised and politicised media. Despite appearances, many of the fundamental aspects of media freedom face significant challenges and, according to recent reports, the situation is only worsening.

Lejla, Nataša, Sara and Elma live their lives within this decline. All in their early to mid-twenties, they represent a generation that had little to do with the war but that bears the burdens of its legacy nonetheless. All four are full-time students, but in their spare time, they’re working towards a fairer, freer future across Bosnia as local correspondents for Balkan Diskurs – a non-profit platform created and run by a regional network of journalists, artists and activists, dedicated to providing objective news (full disclosure: the author of this article works with Balkan Diskurs).

“The media is in the hands of the government. Certain persons dictate which news to publish, how much, and so on,” explains Nataša, from Bijeljina, the second largest city in predominantly Bosnian Serb Republika Srpska, one of the country’s two constituent entities. Sara, from Jajce, confirms that her impression of media within her entity, the predominantly Bosniak and Bosnian Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is the same: “They should be working for public benefit, [but] they are mostly just an arm of parties and political elites.”

Such criticisms will come as little surprise to those who have been tracking the state of media freedom in Bosnia. Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project, Freedom House and Reporters Without Borders have pointed to mounting levels of political pressure and media partisanship. Such pressure takes a variety of forms, but largely stems from the country’s ongoing ethnic and political cleavages. Many media outlets, including Bosnia’s three public broadcasters, are organised along ethnic lines, while some are either aligned, openly affiliated or funded by specific political parties or figures.

As a consequence, skewed media coverage is commonplace and corruption and crime often goes unreported. As Lejla explains: “Many things happening in Visoko are never reported in media, for reasons unknown to me, and those are not small things either – for example there were multiple shootings last month and very little was written about it.”

Media bias, she added, “is most obvious though when political topics from the Federation and Republika Srpska are compared”.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) is a regular victim of such political bias. Much of the local media coverage of the tribunal is skewed and selective. For example, during the closing days of the case against Radovan Karadžić, the Sarajevo-based Dnevni Avaz focused on the prosecution’s charges against the former Bosnian Serb politician, while Banja Luka-based Nezavisne Novine focused solely on his defense and protestations of innocence. Furthermore, only “a handful” of independent organisations in Republika Srpska are known to report on trials within Bosnia’s local War Crimes Court.

Equally as worrying is the fate of those who resist such political pressures. It is not uncommon for journalists and media outlets in both of Bosnia’s entities to face harassment from political, religious and business leaders. Last December, Republika Srpska’s anti-corruption police raided the Sarajevo headquarters of Klix.ba with the aim of identifying the source of a recording published on the news site. Nor are Bosnia’s regulatory agencies immune, as demonstrated by a spate of unidentified attacks against the country’s press council in 2014.

Political pressure is not the only threat to media in freedom in Bosnia. The country’s deteriorating economic situation also presents serious challenges. “Journalists sell their names for trinkets, I guess due to lack of other options or because they are used to taking the easy way out,” Elma explains. “I have witnessed various manipulations by local ‘wannabe journalists’ who publish every single piece of information that lands in their inbox without checking it, not being aware of the consequences,” she adds.

This thoughtless reproduction of news frequently leads to the rapid spread of false information, as demonstrated by the whirlwind of stories surrounding Bosnia’s protests last spring. This phenomenon is only exacerbated by a strong culture of social media use and low levels of media literacy. “The problem is anyone who has internet access can start their own portal or a Facebook page where they will write whatever they want in anyway they see fit… and many people lack critical thinking,” says Elma.

This sad truth has a silver lining though, and it is one all four women subscribe to through their work with Balkan Diskurs and within their local communities: Bosnia’s citizens also have the potential to change the media landscape. “Thinking with your own head and not being a sponge that soaks up everything that is offered [is important],” claims Elma.

Meanwhile her colleagues underline the promise of independent media in terms of media freedom. “Balkan Diskurs gives my voice an opportunity to be heard, so that stories that others keep quiet about can be told; to present my town in a different, more real light. That opportunity, for me, is priceless,” concludes Lejla.

Balkan Diskurs is a non-profit, multimedia platform created and run by a regional network of journalists, bloggers, multimedia artists, and activists who came together in response to the lack of objective, relevant, invigorating, independent media in the Western Balkans. In partnership with Index on Censorship, the site is supporting efforts to map the state of media freedom in Europe.

World Press Freedom Day 2015

• Media freedom in Europe needs action more than words

• Dunja Mijatović: The good fight must continue

• Mass surveillance: Journalists confront the moment of hesitation

• The women challenging Bosnia’s divided media

• World Press Freedom Day: Call to protect freedom of expression

This article was posted on 27 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Apr 15 | Bahrain, mobile, News and features

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

Index on Censorship condemns the extended detention of Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab, who was arrested in early April for detailing abuses at the country’s Jaw prison. On 26 April, Bahraini authorities prolonged Rajab’s detention for a further 15 days.

Rajab tweeted on April 2 that his house had been surrounded by special forces and that over 20 police cars were sent to his house for the arrest.

Rajab was handed down a six month suspended sentence pending payment of a fine in January for a tweet that both the ministry of interior and the ministry of defence said “denigrated government institutions”.

The tweet in question stated:

Since then, Rajab’s appeal against the verdict has been postponed repeatedly.

Rajab, president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and a member of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East Advisory Board, has continuously been targeted by Bahraini authorities over his human rights campaigning work. He reported on 26 February he had again been summoned by the police.

Rajab, a 2012 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression award winner, was released in May 2014 after spending two years in prison on spurious charges including writing offensive tweets and taking part in illegal protests.

“Bahrain must stop the harrassment of Nabeel Rajab,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said. “The country has committed publicly to respecting human rights, but continues to flout its international commitments by denying its citizens the right to peaceful protest, peaceful assembly, and to free expression.”

Last week, Rajab’s civil society colleagues human rights defender Abdulhadi and political activist Salah Al-Khawaja were prevented from attending the funeral of their eldest brother Abdulaziz, who passed away in Bahrain on April 22. Abdulhadi is serving a life sentence due to his human rights work and Salah is serving five years for his political activism; both are prisoners of conscience and torture survivors.

Earlier this year, Bahrain revoked the citizenship of 72 individuals, including journalists, bloggers, and political and human rights activists, rendering many of them stateless – its latest attempt to crack down on those critical of the government.

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar is currently facing

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar is currently facing