26 Jan 15 | News and features, Politics and Society, Sri Lanka

Any nation’s media would be hard pressed keeping track of a landslide of political change, environmental crises, imminent constitutional reform and a general election, all while keeping safe from a generation of assassins used to impunity.

When the media itself needs reform too, the problems might seem overwhelming. This is why Sri Lanka needs a constitutionally recognised national commission to oversee that reform and ensure freedom of expression is properly defended.

Maithripala Sirisena’s unexpected and virtually peaceful election win over incumbent President Mahinda Rajapaksa was quickly painted as a game changer for the country’s media.

He and new Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe began well by lifting blocks on independent news websites banned by the old regime. Exiled journalists were urged to return. Sirisena also promised to use his new authority to investigate the 2009 murder of combative political journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge, whose killers are still free.

But the early offers soon began to look token. There was no matching commitment to identify the killers of cartoonist Prageeth Eknelygoda, who went missing five years ago, or the men behind the notorious “white van” abductions of peaceful activists. In fact Sirisena’s commitment to media freedom looks somewhat qualified.

A series of special expert commissions will be established to oversee an independent review of the judiciary, police, public services, elections, human rights and anti-corruption measures, written into authority by a 19th amendment to the constitution. Pointedly perhaps, the list does not include a commission on the media.

Plans for an independent media commission are not new, and were excluded from what was eventually enacted as the 17th amendment to Sri Lanka’s Constitution in 2001. Media rights groups should steel themselves for a fight to ensure that the much-needed body is not excluded again.

Uvindu Kurukulasuriya, editor of the once banned Colombo Telegraph, thinks it unfortunate that the new government will not establish a media commission, but thinks it was deliberate. “They are not willing to transform state media into (independent) public service broadcasters, and they don’t want to broad-base (collectivise) the state owned Lake House newspaper group.”

The journalist and legal scholar Asanga Welikala calls for the founding of an independent media commission on the recommendation of the constitutional council and representing working journalists, academics, proprietors and new media.

“The commission once constituted would have overall oversight of public service media and would be answerable to parliament,” he argued for the online political journal Groundviews. “Its primary role would be to oversee the public service media institutions, but may include other powers and functions, including the regulation of the (new and traditional) media marketplace, and to promote the freedom of expression in all its forms including through new technology.”

Kurukulasuriya urges action to break the grip of the political appointees heading the country’s major public and private media companies. The co-option of the owners was the subtler side of the old regime’s system of media control, he says. “The previous Rajapaksa regime changed the ownerships of several media institutions through intimidation.”

Self-censorship drove the majority; more deadly means of censorship were reserved for the small cadres of independent journalists who could not be bought or fired, says Kurukulasuriya. Will the government go on reading “media freedom” as owners’ rights, not journalists’ rights?

Reforming the Sri Lankan media is a vast task. The counter-intuitively named Independent Television Network needs privatisation and the nominally public Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC), and the Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation (SLRC), need a proper public service broadcast mandate and an end to political interference. A constitutionally mandated media commission could appoint and “audit” the works of a new independent broadcasting authority founded to oversee their works.

There is justice still to be found too. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Sri Lanka has the fourth worst record on its 2014 Impunity Index, which spotlights countries where journalists are murdered and the killers remain free.

In an open letter to Rajapaksa on the eve of elections, Wickrematunge’s widow Sonali Samarasinghe wrote: “At no time in the history of our country has the freedom of expression so brutally been repressed as it is now. Such media as do operate in the country, have been transformed either into propaganda mouthpieces for you and your brothers, or bullied into submission.”

The state media’s job is to “reflect the line of whatever government is in power,” admitted Rajpal Abeynayake, the editor of the state-run Daily News in a memorable post-election quote to The Guardian’s Amantha Perera. “If the government changes, so does the newspaper. It’s as simple as that. If they want to change that practice they could, but so far no government has done it.”

That Sirisena is showing little inclination to substantively change matters. Bandula Padmakumara — the chairman of the Lake House newspaper group, morning news show anchor and well documented supporter of the Rajapakse family — went just a few hours after the election results came in. But few others have followed.

The new president may have to rely on established partners in self-censorship to help shore up his “fragile, sprawling and diverse” coalition, as the New York Times described it. With parliamentary elections set for late April under Sirisena’s 100 day schedule, the campaign may see old favours be called in and the media expected to help paper over the coalition’s cracks.

Without greater independence the Sri Lankan media will not be able to fairly and accurately report the campaign. International and regional media rights groups need to heap pressure of their own on Sirisena’s new media ministry secretary, Karunarathna Paranawithana, who describes himself on his Facebook page as a “diplomat, journalist (and) political activist”.

The appointment of a constitutionally recognised commission for the media next month would not do much to change the situation in time for the election, but it would send a clear message to embattled journalists that change was on the agenda and risks were worth taking.

According to Sirisena’s own strict timetable, his administration will establish the independent commissions on Wednesday 18 February. There’s still time to add one on media to the list.

This article was posted on 26 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Jan 15 | News and features

Bahrain

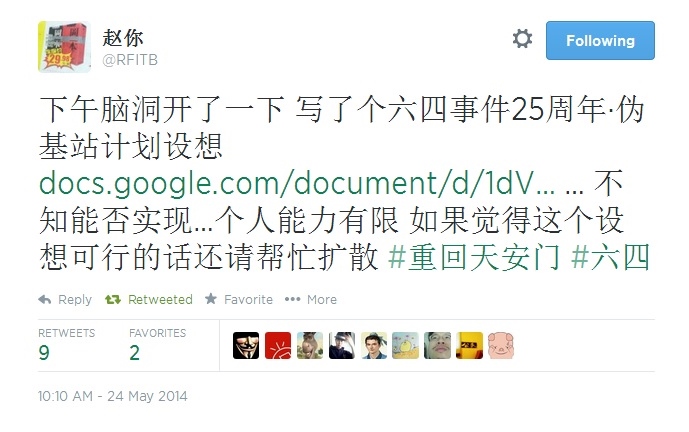

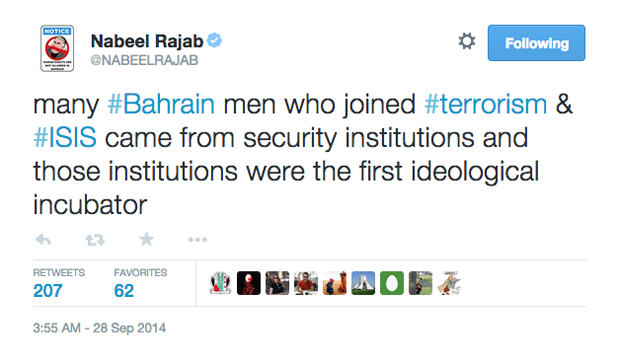

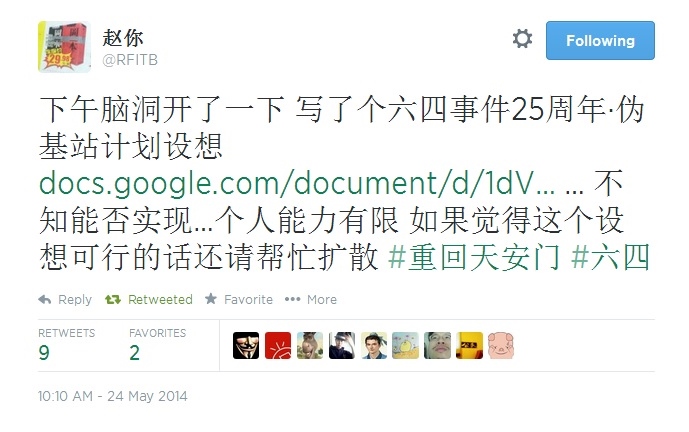

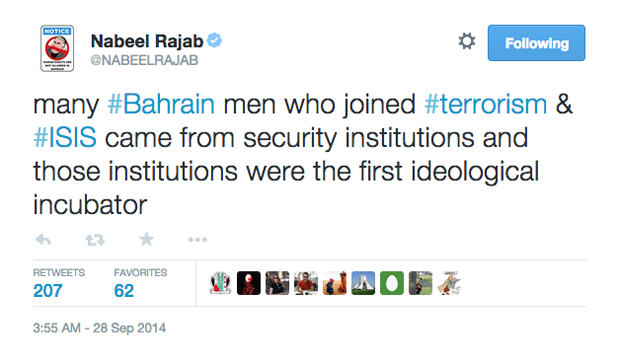

This week, prominent Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was handed down a six month suspended sentence over a tweet in which both the country’s ministry of interior and ministry of defence allege that he “denigrated government institutions”. Rajab was only released last May after two years in prison, over charges that included sending offensive tweets. His experience is not unique in Bahrain. In May 2013, five men were arrested for “insulting the king” via Twitter.

Turkey

A former Miss Turkey was recently arrested for sharing a satirical poem criticising the country’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on her Instagram account. She is set to go on trial later this year. Turkey has a chequered relationship with social media, temporarily banning both Twitter and YouTube in the wake of the Gezi Park protests, in large part organised and reported through social media. In 2013, authorities arrested 25 individuals for spreading “untrue information” on social media.

Saudi Arabia

(Photo: Gulf Centre for Human Rights)

In late 2014, women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets. The charges against her include “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”, according to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights.

France

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)

(Photo: Réseau Voltaire [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Following the series of terrorist attacks in Paris in early January, at least 54 people have been detained by police for “defending or glorifying terrorism”. A number of the cases, including against comedian Dieudonne M’bala M’bala, are believe to be connected to social media comments.

Britain

A 22 year old man was arrested in for “malicious communication” following Facebook messages made in response to the murder of soldier Lee Rigby, and another user was arrested after taunting Olympic diver Tom Daly about his dead father. More recently, police arrested a 19-year-old man over an “offensive” tweet about a bin lorry crash in Glasgow that killed six people. TV personality Katie Hopkins, known for her controversial tweets, was also reported to Scottish police following some tasteless tweets about about Scots. The incident prompted Scottish police the to post their now infamous tweet declaring they would continue to “monitor comments on social media“.

China

Online activist Cheng Jianping was arrested on her wedding day in 2010 for “disturbing social order” by retweeting a joke by her fiance. She was sentenced to one year of “re-education through labour”. Twitter is officially banned in China, and microblogging site Weibo is a popular alternative. In 2013, four Weibo users were arrested for spreading rumours about a deceased soldier labelled a hero and used in propaganda posters. The four were said to have “incited dissatisfaction with the government”, according to the BBC.

Australia

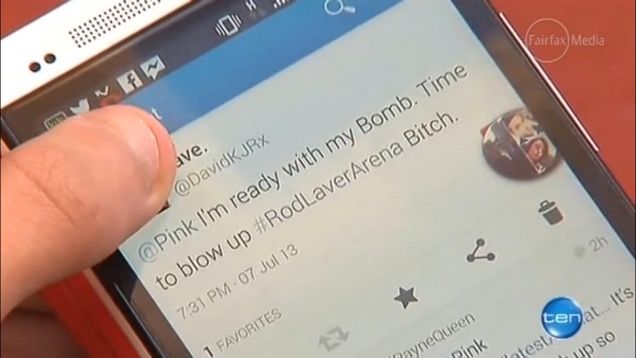

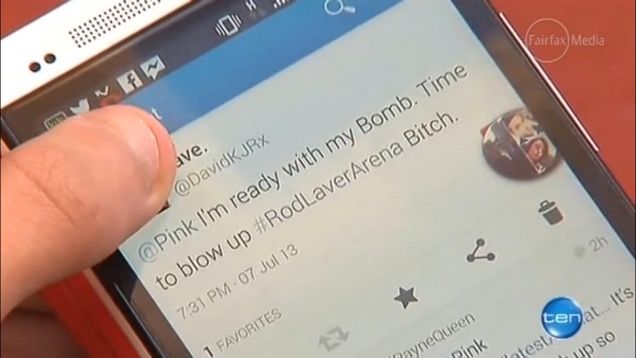

A teen was arrested prior to attending a Pink concert in Melbourne for tweeting: “I’m ready with my Bomb. Time to blow up #RodLaverArena. Bitch.” The tweet referenced lyrics from the American popstar’s song Timebomb.

India

An Indian medical student was arrested in 2012 over a Facebook post questioning why her city of Mumbai should come to a standstill to mark the death of a prominent politician. Her friend was arrested for liking the post. Both were charged with engaging in speech that was offensive and hateful.

United States

Back in 2009, a New York man was arrested, had his home searched and was placed under £19,000 bail for tweeting police movements to help G20 protesters in Pittsburgh avoid the officers. According to Global Voices, it is unclear whether his actions were actually illegal at the time.

Guatemala

A man was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing all their money from banks.

This article was posted on 23 January, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Jan 15 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

Does The Sun’s Page 3 still exist? The paper’s pagination remains, humble but resolute: the very best in British pagination. As surely as curry follows beer on this sceptered isle, the nation’s favourite newspaper will have a third page, facing the second page, on the reverse of the fourth. And despite what those who would disparage our way of life would want, it will always be page three.

Briefly, this week though, it seemed the tradition (est 1970), of putting a picture of a topless young woman on page three — the “Page 3 girl” — had ended. And then it came back. What’s going on? Is there a Page 3 or isn’t there? Or are we witnessing Shroedinger’s glamour shot?

The Page 3 girl was a typical product of the British sexual revolution. What started, with the availability of contraception to women in the 1960s, as a liberation, quickly became another way to reduce them. Freed from the terror of unwanted pregnancy, women and girls were now expected to be in a permanent state of up-for-it-ness. The popular films of the late 60s and early 70s, the On The Buses, the Carry Ons, the Confessions…, portrayed British society as a parade of priapic middle-aged men, always attempting to escape their middle-aged, old-fashioned wives, in pursuit of seemingly countless, always available, young women.

It was fun, it was cheeky, it was vampiric — depending on how you wanted to look at it.

Page 3 was part of this culture; this idea that sweet-natured young women with absolutely no qualms about sex were out there, just needing a wink and a Sid James cackle to persuade them into a bit of slap and tickle. Slap and tickle, though, is not the same as sex, or at least not sex as we might hope to understand it. The slap and tickle of the British imagination owes more to the pre-pill “sort of bargaining” described by Philip Larkin. In spite of the poet’s hopes, sexual intercourse hadn’t really begun in 1963.

Page 3 models were (are? Who knows?) very rarely erotic creatures. They were “healthy” and “fun”, perhaps a little “naughty”; always girls and never women.

The phenomenon survived the attentions of feminist campaigns of varying strengths. Page 3 perhaps peaked in the 80s, when it was possible to move beyond the tabloids to become an actual star, even with clothes on (80s Page 3 icon Sam Fox is still, apparently, in demand as a singer in eastern Europe). This, ironically, coincided with an era of politically correct criticism of Page 3 led by senior Labour MP Clare Short.

In the 90s, new laddism, spearheaded by James Brown’s Loaded magazine, somewhat rehabilitated the Page 3 girl, or, more accurately, made looking at topless models seem respectable to men who would never buy the Sun (“men who should know better” as Loaded’s tagline went).

As the post-Loaded rush for young men’s money descended into boasting of nipple counts, the focus of feminist campaigning switched to the weekly Nuts and Zoo magazines. The Sun’s Page 3 carried on, outliving the rise and fall of Nuts (somehow, Zoo is still going), but is now taking a severe battering from the No More Page 3 campaign, led by young feminists. The very fact that there is uncertainty over the future of the feature is testament to that campaign’s success.

It would be easy to look for a free speech angle on this and come up with “killjoy feminists” versus, decent honest yeomen of England.

But it would be false. In truth, what we have here is an example of how free speech works. The No More Page 3 campaign, as it has pointed out, has a right to call for an end to something they don’t like. They make the argument, they are criticised, and that’s absolutely fine. No one gets hurt, no one goes to court, no one tries to pass a prohibitive law (yet).

Meanwhile, there are some half-hearted defences floating around, mostly attempting to claim that Page 3 is a PROUD BRITISH INSTITUTION, like ugly dogs or barely suppressed tears.

“Tradition!”, the defenders shout, like a legion of leery, thigh-rubbing Topols. The Daily Star, which runs pictures of topless women on its own Page 3, but has escaped the ire of campaigners for the fundamental reason that no one really cares what’s in the Daily Star, proclaimed: “Page 3 is as British as roast beef and Yorkshire pud, fish and chips and seaside postcards. The Daily Star is about fun and cheering people up. And that will definitely continue!”. But really, it all seems a bit half-hearted.

Fundamentally, this week’s wind-up aside, The Sun’s topless Page 3 will cease to exist because people don’t really want it to exist, and no one can really think of a good reason for it to exist.

It’s not censorship, or prudishness, that will eventually kill Page 3. We’ve moved on, regardless of what the editors of The Sun do or say. It’s not them; it’s us.

This article was posted on 22 January, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org.

21 Jan 15 | News and features, United Kingdom

Cressida Brown is the artistic director of Offstage Theatre. The views presented in this guest post are the author’s own.

I have been asked to write about why I decided to initiate Walking the Tightrope, and explain why I think a project exploring how politics and art interact is important and urgent now.

The answers to both those questions lie in the very experience I have had in putting on this festival of strongly opinionated plays which touch on art censorship, cultural boycott, offensive art, and accusations of racism. Throughout I have genuinely felt as if I am walking a tightrope. And now, in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, this feels more so than ever.

Nerve racking questions have stayed unanswered; Should I censor a play about art censorship if it is offensive? Might it offend people? How can I make sure we get a balanced sense of opinions? Is it possible to be neutral hosting these explosive plays? How can I get a debate going but avoid a backlash? How do I make sure I don’t get anyone in trouble, including myself?

The fact freedom of expression seems so complicated to negotiate at the moment is exactly why I think we should raise it.

Last summer I did not feel so cautious when I posted the question “How can this be seen as anti-Semitic?” on to my Facebook timeline. I was referring about the Tricycle Theatre offering to replace Israeli funding of the Jewish Film Festival. I assumed that everyone I was friends with, especially those who were in the arts, would agree with me.

A couple of hours later my page had exploded in over 60 warring comments about the Tricycle but also about the Underbelly decision to cancel an Israeli government funded show.

And then I did something that triggered my eventual decision to initiate this festival. I deleted the entire 60 strong thread from my wall. I had worried how my opinions might be regarded by others. Or whether my politics were going to affect my relationships in the art community. I had self-censored.

Hot on the heels of the Tricycle came the Exhibit B affair. It suddenly started to seem very unwise to post a political view online about what an art venue should or shouldn’t do.

Why was I so worried about others seeing my opinions? Shouldn’t this be what art is about, passionately asserting an opinion? Why had I never found out what my peers opinions were on these topics before? How had I never realised what a thorny and perhaps paradoxical thing Freedom of Expression can be? Why was it that it took 3 controversies hot on the heels of one another for me to begin to ask these questions to myself? Why should it only be in the heat of the moment that I debate these issues with my peers? Why did that debate initiate online and not in person?

I am well aware how explosive this subject can be, and also that it may explode in a very bad way directly back onto me. However I have dedicated my life to this industry, I need to unpack what happened. I can’t have this debate by myself. Now, with some distance from the events of last year, I have decided to do this the only way I know how: theatre.

During this event’s shared experience, the audience responses are just as important as the artists’ vigorous plays. The post show discussions are geared towards replacing a fury of warring tweets with facilitated conversation on Freedom of Expression. The plays are meant to offer a springboard for the post show discussions to leap from. By the end of these festivals I want all of the audience to have listened and experienced greater understanding of their opponents, and considered positions they had never perhaps done before.

Several months have passed since those particular triggering events. I had wondered at times whether the conversation would still be relevant at the beginning of 2015, which seems now like a ridiculous concern. As I write the Charlie Hebdo attack has created solidarity across the world in the defense of free expression and society is left with a mine field of explosive commentary and grief. In other recent news American director Ari Roth has been fired for ‘insubordination’, BP have been told to reveal their funding of the Tate, and Sajid Javid announced his opposition to cultural boycott.

Who knows how these other controversies will have unfolded by the time we are actually performing these plays in front of you…

My hope however is, is that we will continue to meet these controversies with a renaissance in political theatre, discussing liberty through live, tangible art and conversation.

This guest posted was published on 21 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Jan 15 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Letters, Campaigns, Germany, Statements

Chancellor Angela Merkel

Bundeskanzleramt

Willy-Brandt-Straße 1

10557 Berlin

Madam Chancellor,

As members of the international NGO coalition ‘Sport for Rights’ we are appealing to you to make human rights a central subject in your meeting next Wednesday, 21 January 2015, with president Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan.

In recent years, space for political activity and for civil society and journalism in Azerbaijan has gradually been curtailed, and the last six months in particular have witnessed a severe and unprecedented crackdown, with dozens of civil society activists and journalists serving or awaiting sentencing. The country’s most prominent investigative journalist and a number of leading human rights defenders are in prison, punished for their criticism of government policies. Sham charges such as ‘tax evasion’ are used to justify the criminalization of fundamental rights and freedoms.

The ‘Sport for Rights’ coalition has been established to raise this issue in the context of the forthcoming international sporting events to be hosted by Azerbaijan. Against a backdrop of systematic state-sponsored repression, these events will fail to reflect the spirit in which they were established. The next major sporting event is the Baku European Games, designed and regulated by the European Olympic Committees, scheduled for June 2015. A policy shift by the Azerbaijan towards an open society is urgently required if these Games are to be a success. Human rights defenders and journalists must be released, and we urge you to emphasize this point in your conversations with President Aliyev.

This issue is all the more important given that Azerbaijan is a member of the European community of nations: the country is a member of the Council of Europe (CoE), and part of the EU’s Eastern Partnership Initiative. By ratifying the European Human Rights Convention, Azerbaijan has made a commitment under international law to respect the fundamental freedoms contained therein. CoE officials have repeatedly called attention to Azerbaijan’s failure to uphold these freedoms for its citizens. In his retrospective on 2014, Nils Muiznieks, the CoE Human Rights Commissioner, declared:

One of the most difficult situations I have observed is in Azerbaijan, where the authorities are engaging in a systematic crackdown on human rights defenders, media professionals and civil society partners of the Council of Europe. The number of those in detention there or in exile continues to grow.

President Aliyev may point to token releases that take place from time to time – but please remember that not only are these rare, they are issued only after innocent people have served time in prison, losing months and years of their lives for exercising their basic rights to freedom of expression and association.

Among those unjustly arrested or convicted in 2014 are:

- Anar Mammadli and Bashir Suleymanli, co-founders of the Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Centre – Mammadli and Suleymanli were arrested on 16 December 2013 and then sentenced to 5.5 and 3.5 years respectively in May 2014, following outspoken criticism of Azerbaijan’s presidential elections in October 2013. On 29 September 2014, Mammadli was awarded the Václav Havel Award for Human Rights by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.

- Leyla Yunus, Director of the Azerbaijan Institute of Peace and Democracy – Yunus was arrested on 30 July2014, and has remained in pre-trial detention since then, despite serious concerns about her health. She was awardedthe 2013 Theodore Hecker Award in Esslingen-am-Neckar “for her self-sacrificing contribution to the protection of human rights and civil freedoms in Azerbaijan.” Her husband Arif Yunus, Head of the Department of Conflict and Migration Institute of Peace and Democracy in Azerbaijan, Ph.D., a historian specializing in conflict studies, was arrested on 6 August 2014.

- Rasul Jafarov, one of the initiators and coordinators of the “Sing for Democracy” (2012) and “Art for Democracy” (2013) campaigns – Jafarov was arrested on 2 August2014 and has remained in detention since. His trial began on 15 January 2015.

- Intigam Aliyev, human rights defender and lawyer – Aliyev was has been in detention since his arrest 8 August 2014. In his capacity as a lawyer he has specialized in defending rights of citizens in the European Court of Human Rights. At the time of his arrest, he was dealing with over 100 cases pending before the Court.

- Khadija Ismayilova, investigative journalist; radio host for Radio Free Europe/Radio LibertyAzerbaijani service; member of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project – Ismayilova was arrested on 5 December 2014.

We ask you to unequivocally remind Azerbaijan of its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights. Azerbaijan’s partners should insist that this terrible stainon the country’s human rights record is removed before Baku plays host to the European Games, and that these people be released immediately and unconditionally. Full execution of European Court of Human Rights should also be requested from Azerbaijan in this regard, aiming at amending legislation criminalising human rights defenders in line also with recommendations of the CoE Venice Commission.

We sincerely hope that we can count on your principled leadership on this urgentmatter. We thank you for your attention to the concerns set forth herein.

NGO coalition “Sport for Rights”, including:

- Centre for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

- Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (Poland)

- Index on Censorship (Great Britain)

- International Partnership for Human Rights (Belgium)

- Netherlands Helsinki Committee (The Netherlands)

- Norwegian Helsinki Committee (Norway)

- People in Need (Czech Republic)

- Platform (Great Britain)

- Youaid Foundation (Poland)

- A group of civil society activists from Azerbaijan who wish to remain anonymous out

of concern for the security of their family members

20 Jan 15 | Bahrain, Campaigns, News and features, Statements

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

Human rights campaigner Nabeel Rajab was sentenced to six months, which would be suspended pending a fine, Rajab’s lawyer told the BBC.

Rajab has been granted bail while he appeals the verdict in his case.

In October a court ruled that Rajab would face criminal charges stemming from a single tweet in which both the ministry of interior and the ministry of defence allege that he “denigrated government institutions”. Rajab could have faced up to six years in prison.

“Nabeel Rajab has been sentenced for doing nothing more than exercising his right to express an opinion. We condemn the actions of the Bahraini authorities – whose foreign minister marched in Paris to defend freedoms that Bahrain denies the people in its own country. We urge the UK and other allies of Bahrain to join us in calling for this sentence to be overturned,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

In a visit to the Index on Censorship offices in September, Rajab campaigned on behalf of then-detained Maryam Al-Khawaja and spoke about the human rights situation in Bahrain.

19 Jan 15 | Events

Presenting the world premiere of a collection of 12 explosive political five minute plays by writers including Mark Ravenhill, Neil LaBute and Caryl Churchill.

Arising from events and decisions relating to The Underbelly and Incubator Theatre’s The City, Exhibit B and the Barbican, and The Tricycle Theatre.

Each performance will include all twelve five minute plays and a lively post-show discussion exploring freedom of expression in UK arts today. Engage in discussion with the commissioned writers and a range of free expression advocates .

The post-show debate on on Friday 30th January will feature Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

WHERE: Theatre Delicatessen, London, EC1R 3ER

WHEN: Monday 26th – Saturday 31st January, 7:30pm & Sat Matinee

TICKETS: £15 / £12 – available here

This event is produced by Offstage Theatre, in association with Theatre Uncut, and supported by Index on Censorship and Free Word.

19 Jan 15 | Iraq, News and features, United Kingdom

Despite his repeated assertions that it is nothing to do with him, it is now clear that British Prime Minister David Cameron not only has the power to hold back the long-awaited Chilcot Inquiry into the UK’s involvement in the Iraq war until after the election – but may actually do so. The prime minister who championed free speech but wants to duck out of TV election debates seems prepared to suppress the report of the Iraq inquiry on an equally flimsy pretext. If he does he will again find himself on the wrong side of the argument, perhaps with only opposition leader Ed Miliband for company.

The inquiry has been in the headlines a lot lately, with politicians calling for the report to be published before the election and speculative stories about whether this is or isn’t possible. Having significantly compromised to extricate itself from a long-running dispute over which documents it can disclose in support of its findings, the inquiry, launched in 2009, is now undertaking the “Maxwellisation” process of notifying people that it intends to criticise and inviting their responses.

But publication before the election in May will depend not only on when Sir John Chilcot delivers the report to Cameron but what cut-off date is applied. Two weeks ago Cabinet Office minister Lord Wallace re-iterated that the government will hold back the report if it is not completed by the end of February. This is a month before parliament is dissolved on 30 March and pre-election “purdah” officially begins. Wallace justified this early deadline on the grounds that:

part of the previous Government’s commitment was that there would be time allowed for substantial consultation on and debate of this enormous report when it is published.

There was, in fact, no promise of “substantial consultation” from the previous government. It appears to have been invented to lengthen the process and justify interfering with an inquiry whose independence Cameron has repeatedly emphasized. Last month he said: “I am not in control of when this report is published. It is an independent report, it is very important in our system that these sort of reports are not controlled or timed by the government.”

A day after Wallace’s statement, Cameron repeated the error at Prime Minister’s Questions: “…it is up to Sir John Chilcot when he publishes his report. He will make the decision, not me.

A further day later Number 10 issued a “clarification”. According to the Telegraph, the prime minister’s deputy official spokesman said that in fact Cameron would have the final say on the timing the publication once has received the report. She said: “The point the Prime Minister has made is the timing of the report and its completion is a matter for the inquiry. “In terms of publication, the government would seek to publish it as swiftly as possible while ensuring parliament had the right time and opportunity to debate and look at it.”

This looks very much as if Cameron is prepared to suppress the report on the same grounds as Wallace gave – that MPs need a lot of time to study it. But Downing Street clearly knows that if Cameron expressly signed up to the February deadline he would completely contradict his own promise not to control the timing of the report. When I asked one of Cameron’s spokespeople whether he agrees with the deadline, he returned to the pre-clarification position of denial: “as the PM has said in the House of Commons, it is up to the Inquiry, not him”.

Meanwhile Labour leader Ed Miliband has kept very quiet on the issue and, having spoken to Labour’s media people, it is clear that they don’t want to talk about it either.But neither leader can fudge the issue much longer as a cross-party coalition of MPs, including Plaid Cymru, pushes for publication and challenges the government’s deadline. They have now secured a half day parliamentary debate on 29 January. The Lib Dems have challenged the government to publish the report within a week of receiving it, even during the election campaign. Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon called for politicians to unite on the issue, prompting Scottish Labour’s leader Jim Murphy to demand “the earliest possible publication”. Whether that is a rejection of the February deadline is unclear.

Looking further ahead, it seems unlikely that Cameron would really have the nerve to sit on the report, for as long as two months before the election. Even if you accept the official position that it needs to be put before parliament and cannot therefore be published during the election campaign, could he realistically refuse to publish it while parliament is sitting? With MPs treading water during March, to claim that there is not time to debate it would be entirely untenable.

We should never expect too much from an establishment inquiry, particularly without the key evidence. But the government’s argument for stalling the report is effectively that the desire of the political class for the perfect time and space to discuss it trumps voters’ right to be informed. After the massive loss in public trust that the Iraq war caused, surely Cameron wouldn’t dare.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

This article was posted on January 19, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org.

19 Jan 15 | Awards, Campaigns, News and features, Statements

Digital rights champion Martha Lane Fox and bestselling Turkish author Elif Shafak were named today as judges for this year’s Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards.

The awards, presented annually by Index on Censorship, have honoured some of the world’s most remarkable free expression heroes – from conductor Daniel Barenboim to cartoonist Ali Farzat to education activist Malala Yousafzai.

The awards shine a spotlight on individuals fighting to speak out in the most dangerous and difficult of conditions, many of whom are unknown and unsung outside their own countries.

In Azerbaijan, telling the truth can cost a journalist their life… For the sake of this right we accept that our lives are in danger, as are the lives of our families. But the goal is worth it, since the right to truth is worth more than a life without.

— Idrak Abbasov, award winner 2012

Index received more than 2,200 nominations for over 400 individuals and groups from around the world, for the 2015 awards, which are offered in four categories: campaigning (sponsored by Doughty Street Chambers); digital activism (sponsored by Google); journalism (sponsored by The Guardian), and arts.

This year’s judging panel reflects the international scope of the awards. The four judges include award-winning journalist and campaigner Mariane Pearl; bestselling Turkish author, columnist, speaker and academic Elif Shafak; human rights lawyer Keir Starmer, the former UK Director of Public Prosecutions; as well as digital rights campaigner and philanthropist Martha Lane Fox.

The shortlist for the awards will be announced on 27 January and the winners unveiled at a gala ceremony on 18 March at The Barbican, London.

For more information, contact: davidh@indexoncensorship.org

16 Jan 15 | Europe and Central Asia, Guest Post, News and features

World leaders march in Paris following the recent attacks in France (Photo: European Council)

Jacob Mchangama is the founder and executive director of Justitia, a Copenhagen-based think tank focusing on human rights and the rule of law. He has written and commented on human rights in international media including Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, The Economist, BBC World, Wall Street Journal Europe, MSNBC, and The Times. He has written and narrated the short documentary film “Collision! Free Speech and Religion”. He tweets @jmchangama

The brutal attack against Charlie Hebdo has seen European leaders rally round the fundamental value of freedom of expression.

French President Francois Hollande led the way by stating: “Today it is the Republic as a whole that has been attacked. The Republic equals freedom of expression.” Prime Minister David Cameron vowed that Britain will “never give up” the values of freedom of speech, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel called the events in Paris “an attack on freedom of expression and the press — a key component of our free democratic culture.” European Union President Donald Tusk stressed that “the European Union stands side by side with France after this terrible act. It is a brutal attack against our fundamental values, against freedom of expression which is a pillar of our democracy.”

This unified commitment to freedom of expression is both admirable and crucial in the aftermath of the killing of cartoonists armed with nothing more than ink, humour and courage. It is also true that freedom of expression is a fundamental European value and that (Western) Europe allows for a much freer debate than most other places in the world. However, European governments and institutions have long compromised this freedom through statements and laws that narrow the limits on permissible speech. Ironically some of these statements and laws target the very kind of offence that Charlie Hebdo excelled in.

Donald Tusk’s principled defence of freedom of expression stands in stark contrast to a 2012 joint statement issued by then EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton, as well as the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League that “condemn[ed] any advocacy of religious hatred … While fully recognising freedom of expression, we believe in the importance of respecting all prophets”. The statement followed the furore over the crude anti-Islamic film “The Innocence of Muslims”, and suggests that mocking prophets is tantamount to religious hatred prohibited under international human rights law and thus exempted from the protection of freedom of expression.

The controversy over The Innocence of Muslims prompted none other than Charlie Hebdo to print its own depictions of Mohammed, including one showing Islam’s prophet naked. That decision drew stern condemnations from the French government. Then Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius remarked that “in the present context, given this absurd video that has been aired, strong emotions have been awakened in many Muslim countries. Is it really sensible or intelligent to pour oil on the fire?”

While Charlie Hebdo has won a number of lawsuits other French figures have been convicted or censored under French law. Last year comedian Dieudonné M’bala M’bala was banned from performing his comedy shows publicly, due to their anti-semitic content. And France is not alone. Swedish shock artist Dan Park was sentenced to six months imprisonment in 2014, over a number of purportedly racist posters deemed “gratuitously offensive” to minority groups by a Swedish court. The owner of the gallery that had displayed the cartoons was also convicted and the posters ordered destroyed.

In 2011, a prominent Austrian Islam-critic was convicted of “denigration of religious beliefs” for stating that the prophet Mohammed “had a thing for little girls”. An elderly Austrian man was found guilty of the same offence for yodelling while his Muslim neighbour was praying. In the United Kingdom, an atheist who left caricatures of the Pope, Mohammed and Jesus in a prayer room in John Lennon Airport was similarly convicted and sentenced to six months imprisonment, though the sentence was suspended. A TV personality’s disparaging social media comments about Scotland and Scots recently prompted Scottish police to tweet that it would “thoroughly investigate any reports of offensive or criminal behaviour online and anyone found to be responsible will be robustly dealt with”.

France and numerous other European countries also have bans against Holocaust denial. In 2010, a Muslim group claiming to expose free speech double standards in the aftermath of the Danish cartoon controversy was convicted after publishing a cartoon suggesting that Jews have made up the Holocaust.

When it comes to countering terrorism, European states increasingly target not only expression that incites terrorism but also expression that may constitute “glorification”. Exactly a week after the attack against Charlie Hebdo, Dieudonné once again ran afoul of the law and was detained over a Facebook post. According to Le Monde at least 50 other cases of terror apology have been opened against people in France since the attack. In Denmark, a number of Islamists have been prosecuted for glorifying terrorism following Facebook postings that seemingly approved of terrorism, including the assault on Charlie Hebdo. Recently British Home Secretary Theresa May unveiled plans that would ban “non-violent extremists” from using television and social media to spread their ideology.

While Europe has a sophisticated and elaborate regional system for the protection of human rights, these institutions have frequently sided with the censors over citizens. In 2008 the EU adopted a framework decision obliging all member states to criminalise certain forms of hate speech. The European Court of Human Rights has found the confiscation of a “blasphemous” film, the conviction of a French cartoonist mocking the victims of 9/11, and the banning of religious fundamentalist group Hizb-ut-Tahrir compatible with freedom of expression. The Council of Europe’s current High Commissioner for Human Rights Nils Muižnieks, has called for all 47 member states to enact bans against Holocaust denial and gender based hate speech.

These non-exhaustive examples demonstrate that contemporary Europe’s approach to freedom of expression is far more complicated and far less principled than the statements made by its leading politicians in recent days suggest. It is an approach to freedom of expression based on the premise that social peace in increasingly multicultural societies requires restrictions on freedom of expression in order to avoid offending ethnic and religious groups. Thus in 2004, when Dutch film maker Theo Van Gogh was murdered by an Islamist offended by Van Gogh’s controversial and anti-Islamic film “Submission”, the Dutch minister of justice proposed to revive the country’s blasphemy law which had been disused since 1968. He argued that “if opinions have a potentially damaging effect on society, the government must act … It is not about religion specifically, but any harmful comments in general.”

Such sentiments might appeal to pragmatists in the wake of the tragedy in France. But there is little reason to think that restricting freedom of expression fosters tolerance and social cohesion across a Europe increasingly divided along ethnic and religious lines, and where anti-semitism and other forms of intolerance is on the rise. In fact such laws seem to fuel the feeling of separateness of modern Europe by legally protecting group identities against offence rather than fostering an identity rooted in common citizenship. While minorities may be offended by disparaging comments, insisting that freedom of expression be limited to protect them from racism and offence, is a very dangerous game at a time where far-right movements with questionable commitment to liberal democracy are on the rise. In this context it should not be forgotten that Dutch politician Geert Wilders once proposed banning the Quran and that the leader of Front National Marine Le Pen wants to ban religious head wear, including the Jewish kippah. The freedoms that (sometimes) allow bigots to bait minorities are also the very freedoms that allow Muslims and Jews to practice their faiths freely. By further eroding these freedoms, no one is more than a political majority away from being the target rather than the beneficiary of laws against hatred and offence. Only by reaffirming a genuine and principled defence of freedom of thought, expression and religion can Europe hope to create a society built on real tolerance and respect for diversity, and where cartoonists neither have to fear gunmen nor jail, but only the moral judgment of their fellow citizens.

This guest post was published on 16 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Jan 15 | Mapping Media Freedom, Turkey

Çağatay Gürtürk, owner of the collaborative dictionary website ITÜ Sözlük, was detained while trying to enter Turkey on the night of January 14. Authorities were investigating a posting on the site that allegedly “humiliating” to the Prophet Mohammed.

Gürtürk was released shortly after and published an open letter to the press on ITÜ Sözlük’s website saying that the website has been involved in lawsuits over the last ten years.

Gürtürk also wrote on the website, “The freedom to disseminate thought is a universal and constitutional right and people’s websites have become the most valuable tools in the world to use this freedom.”

This article was posted on January 16, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Jan 15 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Letters, News and features

Journalist Seymur Hezi, who works for Index award-winning Azadliq newspaper, is in prison awaiting trial. Hezi was arrested on trumped-up charges of hooliganism on 29 August 2014. The journalist denies the charges, says they are politically motivated and are linked to his work.

Hezi has shared a letter with Meydan TV:

I feel good in the prison. I have no complaints in regard to my health and general mood. There is nothing different besides that I miss my friends and relatives. I think about what is going around and read much. I wouldn’t like to waste my time. I don’t know how much time I’ll spend here, so I don’t want to lose this period. My advice to the youth in freedom is that, wasting time for nothing is unacceptable, whatever the conditions are.

Sometimes I get some newspapers. Recently, I’ve read in one of them the letter Khadija Ismail wrote from the prison and I was impressed. Maybe, the very first reason is that we are very close here from the viewpoint of distance. Here, in Kurdakhany, the distance between us may be some 100 feet, only. Maybe, even less. The author of the letter is kept some 100 feet away me.

I possess strange feelings after reading her letter. The letter full of will and determination has been written by a woman. An Azerbaijani woman. You know that we had many of such determined and strong-willed women in our history. But such determination and will of struggle in a woman in prison… It is a true historical event. It is the history of our will, determination and decisiveness. Particularly, of our women…

Khadija Ismail is one of the greatest examples of righteousness truthfulness and the direct expression of true words. For her, there is only truth and nothing else and it is right, whatever the arguments are. It is right despite of all obstacles in front of her. She is being tested for it every single day.

I don’t know whether we owe it to extreme patriarchal state of our society or something else, expressing the power, endeavor and bravery of a woman, our fathers have always said: “Sheis a woman like a man”. Today, observing a woman like Khadija, we can change this saying. For expressing the manhood and will of a man, I would say: “He is a man like the Azerbaijani woman” or more correctly: “He is a man just like Khadija”.

My greetings to my friends and relatives. I kiss and hug all of you. Wish to reach beautiful days of freedom. Earlier or later, we will meet soon. I love you.

Your friend,

Seymur Hezi

01/13/2015

This article was originally posted on 14 January 2015 at meydan.tv. It is reposted here with permission.

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)