23 Dec 14 | Africa, Awards, News and features

Daniel Bergner is an author and journalist who writes for New York Times Magazine; in 2005 he won an Index award for his book Soldiers of Light, which told the stories from inside war-torn Sierra Leone.

West Africa, and Sierra Leone in particular, has been receiving extensive media coverage due to the Ebola outbreak affecting the region. Bergner says that although he has been back to West Africa since writing the book, a story he was hoping to cover in Sierra Leone is “very unlikely to succeed” because of the outbreak.

Bergner’s latest book, What Do Women Want?: Adventures in the Science of Female Desire, was published in 2013 and has been translated into 15 languages.

Explore the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards

This article was posted on 23 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Dec 14 | Europe and Central Asia, Magazine, News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

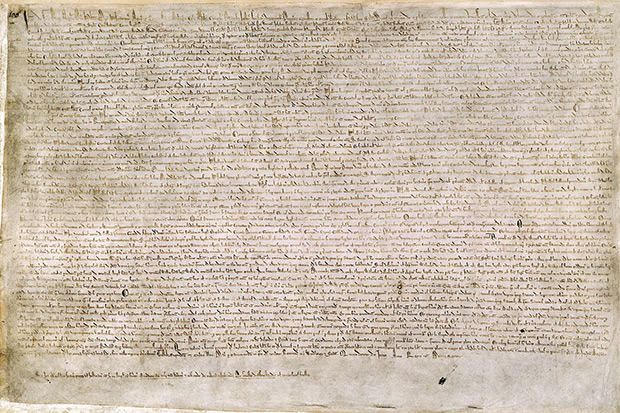

2015 marks the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta. Index on Censorship magazine’s winter issue has a special report that examines all ways in which the document affected modern freedoms. Here John Crace kicks us off with a tongue-in-cheek trip through history

Call it a free for all. Call it an innate sense of fair play. Call it what you will, but the English had always had a way of making their feelings known to a monarch who got a bit above himself by hitting the country for too much money in taxes or losing overseas military campaigns or both. They rebelled. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t but it was the closest medieval England had to due process. Then came John, a king every bit as unloved – if not more so – as any of his predecessors; a ruler who had gone back on many of his promises and was doing his best to lose all England’s French possessions and all of a sudden the barons had a problem. There wasn’t any obvious candidate to replace him.

So instead of deposing him, they took him on by limiting his powers.

Kings never have much liked being told what to do and John was no exception. If he could have got out of cutting a deal with the barons he would have done. But even he understood that impoverishing the people he relied on to keep him in power hadn’t been the cleverest of moves, and so he reluctantly agreed to take part in the negotiations that led to the sealing of The articles of the Barons – later known as Magna Carta – at Runnymede on 15 June 1215. Which isn’t to say he didn’t kick and scream his way through them before agreeing to the 61 demands which were the bare minimum for his remaining in power. He did, though, keep his fingers cunningly crossed when the seal was being applied. As soon as the barons had left London, King John announced — with the Pope’s blessing — that he was having no more to do with it. The barons were outraged and went into open rebellion, though dysentery got to King John before they did and he died the following year. Don’t shit with the people, or the people shit with you. Or something like that.

With the original Magna Carta having lasted barely three months, there were some who reckoned they could have saved themselves a lot of time and effort by topping King John rather than negotiating with him. But wiser – or perhaps, more peaceful – counsel prevailed and its spirit has endured through various subsequent mutations – most notably the 1216 Charter, The Great Charter of 1225 and the Confirmation of Charters of 1297 and has widely come to be seen as the foundation stone of constitutional law, both in England and many countries around the world. It was the first time limitations had been formally placed on a monarch’s power and the rights of citizens to the due process of law and trial by jury had been affirmed. Well, not quite all citizens. When the various charters talked of the rights of Freemen, it didn’t mean everyone; far from it. Freemen just meant that small class of people, below the barons, who weren’t tied to land as serfs. The Brits have never liked to rush things. They like their revolutions to be orderly. The underclass would just have to wait.

Magna Carta and its derivative charters were never quite the symbols of enlightened noblesse oblige they are often held to be. The noblemen didn’t sit around earnestly thinking about how they could turn England into a communal paradise. What was the point of having fought and back-stabbed your way to the top only to give power away to the undeserving? The charters were matters of political expedience. The nobles needed the Freemen on their side in their face-off with the king and an extension of their rights was the bargaining chip to secure it. Benevolence never really entered the equation. Nor was Magna Carta ever really a legal constitutional framework. Even if King John hadn’t decided to ignore it within months, it would still have been virtually unenforceable as it had no statutory authority. It was more wish-list than law.

Ironically, though, it is Magna Carta’s weaknesses that have turned out to have guaranteed its survival. Over the centuries, Magna Carta has become the symbol of freedom rather than its guarantor as different generations have cherry-picked its clauses and interpreted them in their own way. While wars and poverty might have been the prime catalyst for the Peasant’s Revolt against King Richard II in 1381, it was Magna Carta to which the rebellion looked for its intellectual legitimacy. The Freemen were now seen to be free men; constitutional rights were no longer seen as residing in the few. The King and his court were outraged that the peasants had made such an elementary mistake as to mistake the implied capital F in Freemen for a small f and the leaders were executed for their illiteracy as much as their impudence.

Bit by bit, starting in 1829 with the section dealing with offences against a person, the clauses of Magna Carta were repealed such that by 1960 only three still survived. Some, such as those concerning “scutage” — a tax that allowed knights to buy out of military service — and fish weirs, had become outdated; others had already been superseded by later statutes. Two of those that remained related to the privileges of both the Church of England and the City of London — a telling insight into the priorities of the establishment. Those who still wonder, following the global financial collapse of 2008, why the bankers were allowed to get away with making up the rules to suit themselves need look no further than Magna Carta. The bankers had been used to getting away with it for the best of 800 years. You win some you lose some.

The survival of clause 39 of the original Magna Carta has been rather more significant for the rest of us. “No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.” Or in layman’s terms, due process: the legal requirement of the state to recognise and respect all the legal rights of the individual. The guarantee of justice, fairness and liberty that not only underpins – well, most of the time – the UK’s constitutional framework, but those of many other countries as well.

Britain has no written constitution. Not because parliament has been too lazy to get round to drawing one up, but because one is already assumed to be in the lifeblood of every one living in Britain. Queen Mary may have had “Calais” written on her heart, but the rest of us all have “Magna Carta” inscribed there. It can be found on the inside of the left ventricle, for those of you who are interested in detail. Other countries haven’t been so trusting in the genetic inheritance of feudal England and have insisted on getting their constitutions down in non-fugitive ink.

That Magna Carta has also been the lodestone for the constitutions of so many other countries, most notably the USA, is less a sign of the global reach of democratic principles – much as that might resonate with romantic ideals of justice — than of the spread of British people and British imperial power. After the Mayflower arrived in what became the USA from Plymouth in 1620, the first settlers’ only reference point for the establishment of civil society was Magna Carta. The settlers had a lot of other things on their minds in the early years — most notably their own survival and the share price of British American Tobacco — and they hadn’t got time to dream up their own bespoke constitution. If they had, they might have come up with something that abolished slavery and gave equal rights to black people sometime before the 1960s. So they settled for an off-thepeg version of Magna Carta, with various US amendments. And some poor spelling. In 1687 William Penn published the first version of Magna Carta to be printed in America. By the time the fifth amendment — part of the bill of rights – was ratified four years after the original US constitution in 1791, Magna Carta had been enshrined in American law with “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.”

The fact that the American idea of Magna Carta was not one that would necessarily have been recognised in Britain was neither here nor there. For the Americans, the notion of the rights of a people to govern themselves was more than something that had been fought for over many centuries – a gradual taking back of power from an absolute ruler — that had been ratified on paper. They were fundamental rights that pre-existed any country and transcended national borders. And even if there was no one left alive on Earth, these rights would remain. They might as well have been handed down by God, though it’s probably just as well Adam hadn’t read the sections on the right to defend himself and bear arms. If he had shot the serpent, the whole history of the world might have been very different. As it is, when the Americans took on the British in the War of Independence, they weren’t fighting against a colonial overlord so much as for their basic rights to freedom.

The distinction is a subtle but important one. For though the more recent constitutions of former British colonies, such as Australia, India, Canada and New Zealand, more closely reflected the way Magna Carta was understood back in the mothership, those interpretations of it were still very much a product of their time. As a historical document, Magna Carta remains fixed in the 13th century: a practical solution to the problem of an iffy king. But as a concept it is a shifting, timeless expression of the democratic ideal. It can mean and explain anything. Up to and including that Britain always knows best.

Yet the appeal of Magna Carta endures and it remains the gold standard for democracy in any debate. Whatever side of it you happen to be on. British eurosceptics argue that the UK’s continuing membership of the European Union threatens the very parchment on which it was written; that Britain is being turned into a serf by a European despot. Pro Europeans argue that the EU does more than just enshrine the ideals of Magna Carta, it turns the most threatened elements of it into law.

Eight hundred years on, Magna Carta remains a moving target. Something to be aspired to but never truly attained. A highly combustible compound of idealism and pragmatism. Somehow, though, you can’t help feeling that King John and the feudal barons would have understood that. And approved.

This article is from the Winter 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine as 1215 and all that.

This article was originally posted on Dec 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Dec 14 | Belarus, Digital Freedom, News and features

Belarusian authorities attempt to hide a financial crisis by silencing critical voices in a new clampdown on media.

Several independent news sites were blocked in Belarus on 20 December. They include Naviny.by, Charter97.org, belaruspartizan.org, UDF.by, gazetaby.com, onliner.by and the website of BelaPAN, the only independent news agency in the country. No official explanations have been provided so far.

“It is still unknown who did that and for what reason. However, it is clear that the decision to block the ID addresses could only be made by authorities as in Belarus the government has monopoly on providing IP addresses,” the statement of BelaPAN Information Company reads.

These actions coincided with the decision of the government to introduce a 30% fee for purchasing of foreign currency as expectations of devaluation grew among the population of Belarus. On Saturday, Liliya Ananich, the Information Minister, gathered editors of leading non-state media and advised them “not to escalate the panic in the Belarusian society”. According to the minister, the coverage of the financial crisis in independent media “contravenes the interests of the state”.

“In times like these all media, both state and non-state, must work for the country,” Ananich told the editors, and warned that those who do not get the message might face sanctions.

Just three days before that, on 17 December, the parliament of Belarus adopted amendments to the Media Law that provides for official status of mass media for online news publications. Thus, online media might face the same restrictions, warnings and even closure for infringements of the Media Law as offline. The Law was adopted urgently without any discussions with civil society and independent professional community. It comes into force from 1 January 2015 – but, as it turns out, the authorities do not need any legal provisions to block news sites.

The special services of Belarus have a significant arsenal of means of blocking content online that they have used before. As it was revealed in Index’s Belarus: Pulling the plug policy paper, there are different ways the state authorities restrict freedom of expression online, including a repressive legal framework, online surveillance, website blocking and filtering, and cyber-attacks against independent websites and content manipulation.

The recent developments show the authorities of Belarus have no intention to stop its restrictive practices towards free speech. Internet has remained the last relatively free domain of freedom of expression in Belarus. As the country is moving into 2015, the year of the next presidential election, this space looks set to be shrinking further.

This article was posted on 22 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Dec 14 | Bulgaria, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society

Murky ownership, a whole array of censorship practices as well as corruption are plaguing Bulgarian media, according to a survey from the Bulgarian Reporter Foundation.

The report, Influence on the Media: Owners, Politicians and Advertisers, is based on surveys with 40 media outlets carried out between January and September 2014. One hundred journalists and 20 media owners were questioned about their perception of censorship in the Bulgarian media.

The report found that journalists, senior editorial staff and owners are offered bribes by politicians and corporations. While these allegations are very difficult to prove, there is a widespread assumption among people working in the media that reporters in certain sectors receive regular payments from large companies to present them in favorable light.

“It is very hard to prove the (existence of) bribes”, said Dr. Orlin Spassov, one of the authors of the report, who is an associate professor in media and communication studies at Sofia University and executive director of Media Democracy Foundation.

There are no court cases related to the bribes, Spassov told Index. “We collect the information using anonymous interviews. In other circumstances, journalists would hardly share such statements. Even under conditions of anonymity guaranteed, some of them were afraid to speak.”

Bribes can come in many different forms, the report found. From low-interest rates offered by certain banks to luxury trips, expensive presents or even as little as the payment of a phone bill.

Corruption among editors-in-chief is also considered a widespread phenomenon. The report mentions an editor-in-chief who received a record-high amount of 5 million Leva (EUR 2,5 million GBP 2 million) for changing the orientation of a media outlet to support a political party.

Media owners are also seen as corrupt. A leaked document, which was posted online, showed that a football club transferred five-digit amounts to a sports daily for its “favorable attitude”. According to journalists, media outlets sometimes blackmail companies or local authorities by threatening negative coverage unless the target buys advertising in the publication.

According to the report, the lack of media ownership transparency is one of the biggest problems. There are a number of media outlets owned by off-shore companies, anonymous joint stock companies or bogus owners. Even if the owners are known, it is sometimes difficult to see their interests and their finances. Public registers show that in Bulgaria the majority of media outlets are making losses. The fact that a number of prestigious foreign media companies have withdrawn from the Bulgarian market in recent years made things even fuzzier.

Documents that emerged after the Corporate Commercial Bank crisis showed that politics, mass media and finances are entangled in an unhealthy knot. This marks the relationship between journalists and media owners, the report points out.

There is no clear border between the owners and the senior editors. Thirty-five per cent of the surveyed senior editors say that the owner interferes with their work. Moreover, 20 per cent stated that they are sanctioned if they refuse to follow the owner’s instructions. Thirty-six per cent of the journalists consider that there are things they cannot tell the public through their media and 16 per cent confess that they are not convinced on everything their publication publishes.

A number of media owners see their media outlets as a tool for helping or protecting their other business interests. In May 2014, an internal document was published containing instructions given by one of the owners of an influential media group to the journalists of his papers and website on how to cover an issue about the withdrawal of licenses of electricity distribution companies.

The broader the audience a media outlet has, the stronger the pressure it faces from politicians. In Bulgaria, it is a common practice that MPs or members of the government call or send SMS messages to owners, senior editors or even journalists if they are not happy with their coverage.

If a media outlet does not comply with their demands, politicians often deprive “unfriendly” media of information. Their reporters would not be invited to certain events or do not receive information which their competitors are given access to. If politicians are reluctant about a certain topic, they would refuse to participate in the talk programs. Because journalists are obliged to present all points of view, they need to drop the topic from the agenda.

Sometimes authorities also misuse the Access to Public Information Act to obstruct the access to certain media outlets. When journalists request information from ministries and other departments, they are asked to file a freedom of information request that are replied only after 14 days, the period mandated by law.

The main leverage of central and local authorities over the media is the publication of paid announcements. This is an important source of revenue for Bulgarian media, especially because advertising has strongly declined due to the economic crisis. The report cites an editor-in-chief saying that the biggest advertiser is the state. Openly there are no conditions posed to obtain advertisements, but there is an assumption that critical media outlets will not receive contracts.

Commercial advertisers also have a strong influence on the editorial output of Bulgarian media. Companies routinely ask for materials that present them in a positive light as a condition of buying advertising. Sometimes they ask outlets to play down or ignore customer complaints or run critical coverage of their competitors. Many times there is no clear differentiation between the sponsored and editorial content, the report found.

Intra-editorial censorship is also widepsread in the Bulgarian media. Easily controllable, loyal journalists are promoted into responsible positions. They make sure political positions and orders are given a professional justification, this way reporters do not feel the political pressure from their peers. Sometimes negative comments are erased from the internet.

Personal blogs are seen as a way to circumvent editorial influence, with more or less result. In one case a journalist had to close his blog after he came under pressure from the senior editorial staff. In some media outlets, journalists are forbidden to have personal blogs, other owners allow them only by written authorization.

The survey and report were completed with the support of the Sofia office of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and its Media Program South East Europe.

For more on media violations in Bulgaria, visit mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

This article was posted on 22 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Dec 14 | India, News and features

The state of free speech in India remains a cause for concern judging by the rise in recorded attacks on the media and the increasing use of defamation suits — the most marked trends in 2014.

The figure for attacks on the media rose sharply with better data collection. There were at least 85 attacks this year. For the first time, since January 2014, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) has begun collecting data on attacks on the media as a separate category.

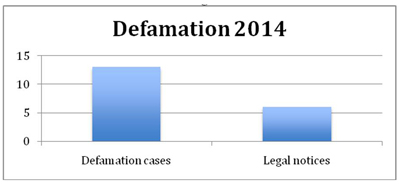

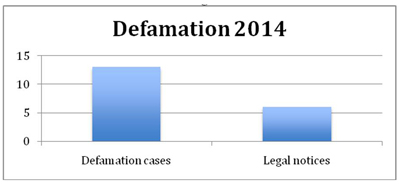

Reported cases of defamation and legal notices alleging defamation totaled 21 in 2014 (till December 15). Of the eleven new cases recorded, seven were filed against media, two against college publications, and 3 against individual politicians. Two were court orders against publishers, a total of 14. Those against the media included the cases filed by Justice Swatanter Kumar and Indian captain M.S. Dhoni; politician Gurudas Kamat, and the Sahara Group.

In addition, one defamation conviction was upheld in a case filed earlier, against Vir Sanghvi when he was at the Hindustan Times.

Seven legal notices were served during the year — five to media houses, one to a marketing federation for the advertisement they ran, and one to journalist-authors. The last was sent by Mukesh Ambani-led Reliance Industries Ltd to Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and other authors of the book Gas Wars: Crony capitalism and the Ambanis. A Rs 100 crore notice was sent by industrialist Sai Rama Krishna Karuturi, Managing Director of Karuturi Global Ltd, to environmental journalist Keya Acharya. Infosys, and a former police commissioner in Pune also served legal notices on the media in the year gone by.

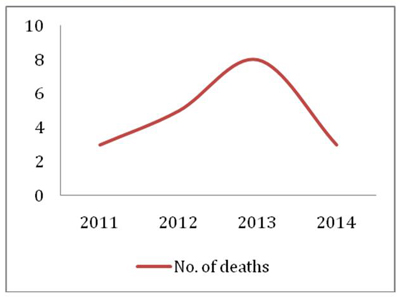

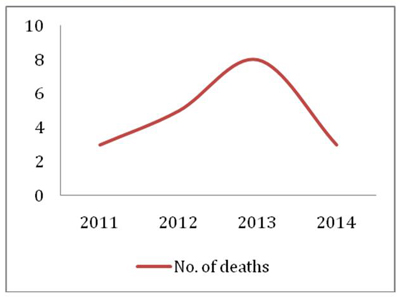

There was a drop in the deaths of journalists from eight in 2013 to two this year. However, a hate crime was recorded in the death of a software engineer in Pune, underlining the spike in hate speech cases. Apart from censorship across media and of books, theatre and film, there were at least 85 cases of attacks on journalists, 62 of which were from Uttar Pradesh alone.

These and other instances form part of the reported cases in the Free Speech Tracker of the Free Speech Hub till December 15, 2014. A project of the media watch site The Hoot the Free Speech Hub has been monitoring freedom of expression in India since 2010 and this is its fifth annual report. The tracker looks at a range of issues, including journalists’ deaths, attacks on journalists and on citizens, threats and arrests arising out of free speech issues, censorship, defamation, privacy, contempt, surveillance, and hate speech.

Seven defamation notices, and six legal notices were against media houses or journalists. In addition police complaints alleging defamation were also filed. The defamation cases also resulted in gag orders against the media, drawing criticism from the Editors Guild of India but to no avail. A defamation case filed by former President of the BJP, Nitin Gadkari also resulted in the arrest of Aam Aadmi Party leader Arvind Kejriwal in May, for calling the former corrupt. Kejriwal refused to furnish a bail bond and was remanded to judicial custody. The latest case, a Delhi police directive to radio stations to stop broadcasting a jingle from the Aam Aadmi Party on the grounds of defamation, only served to illustrate the extreme sensitivity of the powers that be to any criticism.

Clearly, defamation cases act as a pressure and silencing tool. Congress spokesperson and former minister Manish Tiwari faced arrest in a criminal defamation case filed by former BJP President Nitin Gadkari for alleging that the latter held a ‘benami’ flat in the Adarsh housing society. But after a summons was issued for his arrest, Tiwari submitted an unconditional apology and the case was withdrawn.

In another case, the Sahara media group filed a defamation case against Mint editor Tamal Bandopadhyay and the Kolkata High Court stayed the release of his book, Sahara: The Untold Story but a disclaimer and a settlement followed and the case was withdrawn.

Hate speech remains on the fault lines of free speech and, given the unabashed use of hate propaganda during the campaign for the 16th Lok Sabha elections, there was a sharp spike in the number of hate speech cases to 20 this year, double the 2013 figure.

The arrest of people for Facebook posts continued, despite clear guidelines issued on cases related to Section 66 (A) of the Information Technology Act in the wake of the arrest of two students from Palghar in 2012 and a pending case challenging the provisions before the Supreme Court of India. Sedition cases also cropped up; a student was arrested in Kerala for sedition for remaining seated while the national anthem was being played in a cinema.

Apart from the ignominious cave in by book publishers to the demands of Hindutva organisations, as in the case of the Wendy Doniger book The Hindus, other attacks on the media and civil society activists and violence by vigilante groups bent on imposing a regressive moral agenda, added to the potent brew for free speech violations in 2014.

Highlights

Deaths : Two journalists and a victim of a hate crime

There has been a drop in the deaths of journalists from eight in 2013 to two this year. Tarun Acharya in Odisha and M.N.V. Shankar in Andhra Pradesh were brutally killed days after reporting on malpractices by local business people.

The third death, of 24-year old Mohsin Shaikh, a software engineer in Pune, was triggered by a Facebook post allegedly defamatory to 17th century Maratha ruler Shivaji and the late Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray. The engineer had no connection with the Facebook post but was targeted because his beard indicated his identity as a Muslim. Police arrested the founder of the Hindu Rashtra Sena, Dhananjay Desai, for a hate crime.

In 2013, eight journalists died, including Sai Reddy who was killed by Maoist groups in Chhattisgarh. In April 2014, these groups admitted that killing Reddy was a mistake. There were five deaths in 2012 and three in 2011.

Defamation cases and legal notices increase to 21

Defamation cases and legal notices threatening defamation had a chilling effect on freedom of expression with 21 instances being recorded through the year, an increase from the two cases in 2012 and seven in 2013. From politicians to business houses, lawyers, former judges and media houses, defamation notices were sent against book publishers, advertisers, other media houses and journalists.

Arrest of 13 persons, including a journalist under NSA, a student for sedition and three persons for Facebook-related content

In Kerala, nine students were arrested for a crossword clue in a college magazine allegedly unfavourable to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Other arrests included a journalist from Assam, allegedly due to links with insurgency groups and a student from Kerala on charges of sedition for remaining seated while the national anthem was being played in a cinema and three others for Facebook-related content.

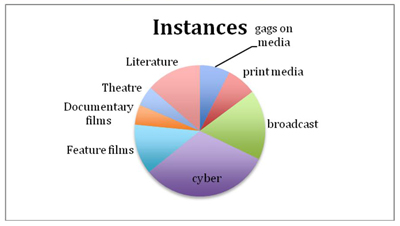

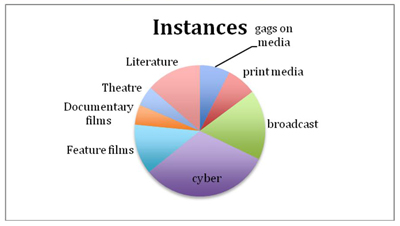

Censorship: 85 instances

The number of instances of censorship this year fell to 86 from 99 in 2013 and 74 in 2012. Internet-related censorship fell marginally from 32 in 2013 to 27 this year. Ten of these instances were related to Facebook posts that attracted cases and triggered violence in at least three instances. There were 25 instances of censorship in print and the broadcast media, including five gag orders on media reportage and one on radio broadcasts of an advertisement.

Censorship showed an overall decrease from 99 instances last year to 85 this year. However, censorship in the broadcast media saw an increase to 14 instances, besides five instances of gags on media coverage of sensitive issues being obtained by a range of people, including former judges charged with sexual harassment and sports bodies and educational institutions.

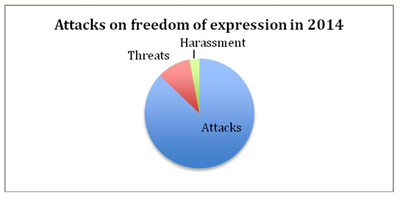

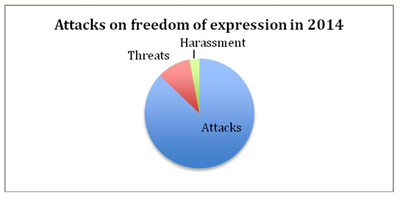

Attacks, threats and harassment: 101 instances

Direct physical attacks on the media and on citizens for freedom of expression issues remained high, with at least 85 cases of attacks recorded by the media alone in 2014. In addition, there were three attacks on other citizens, ten cases of threats and three of harassment.

For the first time, the National Crime Records Bureau has begun collecting data on attacks on the media as a separate category from January this year. In a written reply to a question in the Lok Sabha, the Minister of State for Information and Broadcasting Rajyavardhan Rathore said that, up to June, 62 of these cases occurred in Uttar Pradesh.

According to the Minister’s reply, up to August 8, there were six cases each in Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, with no arrests in Bihar but eight in Madhya Pradesh. Cases of attacks on the media were also registered in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Assam and Meghalaya and seven people were arrested in connection with the cases in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Meghalaya.

While more details are awaited on these attacks and on how many were related to professional work, the Hoot’s Free Speech Tracker has details of 18 instances of attacks and 12 instances of threats recorded this year. Of these, 15 attacks and nine threats were directed at the media, including a police assault on journalists covering news events, the sand mafia attacking an environmental journalist, separate instances of a petrol bomb and gunshots fired on the homes of journalists and reports of journalists being used as ‘human shields’ in Kashmir.

Sharp spike in hate speeches

This year saw the sharpest rise in hate speeches from two in 2012 and ten in 2013 to 22, peaking in the run-up to what was billed as the most divisive general election in India’s history. Apart from riots that broke out due to the circulation of videos or inflammatory messages, instances of hate propaganda and riots marked the increase in hate speeches in the country and, given the scheduled elections to various state assemblies, shows no signs of abating till the end of the year — witness the reports of the hate speech made by BJP Minister Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti in December 2014.

Snapshot of the last three years

| Categories |

2014 |

2013 |

2012 |

Deaths of journalists

Death due to hate crimeTotal |

02

0103 |

08

|

05 |

Attacks on the media

Attacks on citizens

Threats

Harassment

Arrests/detentionsTotal |

85

03

10

03

04105 |

20

04

0225 |

39

|

| Censorship :

Gags on all media

Print

Electronic media

Internet

Feature films

Documentary films

Theatre

Art

Music

Literature and educational curriculum

Total |

06

06

14

26

10

04

04

–

0511

86 |

15

11

32

21

02

02

03

06

07

99 |

08

04

41

14

07

74 |

| Privacy & Surveillance |

08 |

13 |

05 |

Defamation cases

Legal notices

Court order Total |

12

07

0221 |

07 |

02 |

Hate speech

Hate propagandaCourt cases on hate speech restrictions |

20

0202 |

10 |

02 |

| Policy, regulation |

02 |

07 |

03 |

Sedition (including three withdrawals)

Contempt

Legislative privileges |

05

03 |

02

02

01 |

|

The year in review

Free speech violations in 2014 included the death of two journalists for their investigative stories on malpractices in local businesses, the killing of a young software engineer in Pune for what police termed a ‘hate crime’, an increase in defamation cases and legal notices to curb reportage of a range of issues, increasing attacks on the media and civil society activists, violence by vigilante groups and a spike in hate speech cases during various election campaigns.

While the number of deaths of journalists for their work may have fallen from the eight of the preceding year to two this year — Tarun Acharya and M.N.V. Shankar – they underline the extreme vulnerability of journalists working in small towns, particularly on unearthing crimes.

Acharya, 29, was a stringer for Kanak TV in Odisha and was killed on May 27 in Khallikote town of Ganjam district. He had done an investigative story on the alleged employment of children in a cashew processing plant owned by one S. Prusty. Shankar, 52, a senior correspondent with Andhra Prabha newspaper, was killed in Chilakaluripet town of Guntur district on May 26, a few days after his newspaper published his report on the kerosene oil mafia. While the police arrested two persons in connection with Acharya’s murder, Shankar’s killers have yet to be found.

Attacks, arrests

This year saw an increase in attacks on the media, as officially recorded by the National Crimes Bureau for the first time, an increase in threats to journalists as well as the arrests of journalists for alleged involvement with insurgency groups and the arrest of citizens for posts on social media.

Of the eight cases linked to Facebook posts, one person was arrested for a post allegedly against West Bengal Chief Minister Mamta Banerjee; an Aam Aadmi Party activist was arrested for forwarding an allegedly anti-Modi text in Karnataka; a student was arrested for allegedly mocking the national anthem in Kumta, Karnataka; and in Kerala, a student was arrested for sedition for allegedly insulting the national anthem by remaining seated while it was being played in a local theatre.

Defamation

The intimidating effect of a possible defamation suit was clearly on the rise as 2014 recorded 21 instances of defamation against individuals and the media. These included 13 cases of defamation and six legal notices, besides one court order.

In May, Aam Aadmi Party leader Arvind Kejriwal was arrested in a defamation case filed by former president of the BJP, Nitin Gadkari, for calling the latter corrupt. He refused to furnish a bail bond and was remanded to judicial custody.

Former Supreme Court judge and National Green Tribunal Chairperson Justice Swatanter Kumar filed a defamation case against two English television channels and a leading English newspaper as well as a law intern who had filed a complaint of sexual harassment against him. He also managed to get a gag order on media reportage of the case.

In another case, India cricket captain M.S. Dhoni filed a Rs 100 crore defamation case in the Madras High Court against media houses Zee Media Corporation and News Nation Network over allegations of his involvement in match-fixing.

Clearly, defamation cases serve to silence people. Congress spokesperson and former minister Manish Tiwari faced arrest in a criminal defamation case filed by former BJP President Nitin Gadkari for alleging that the latter held a ‘benami’ flat in the Adarsh housing society. But after a summons was issued for his arrest, Tiwari submitted an unconditional apology and the case was withdrawn.

In another case, the Sahara media group filed a defamation case against Mint editor Tamal Bandopadhyay and the Kolkata High Court stayed the release of his book, Sahara: The Untold Story, but a disclaimer and a settlement followed and the case was withdrawn. Given that decriminalizing defamation has been a long-standing demand of journalists’ organisations, it is ironical that a media group such as Sahara should resort to defamation notices.

It was not the only one. India TV sent a defamation notice to aggrieved employee Tanu Sharma who had alleged sexual harassment and had attempted suicide outside the company’s office. It also sent a defamation notice to media watch site Newslaundry which carried a report on the incident.

Among the other cases, Infosys sent notices of Rs 2000 crore each to three publications owned by Bennett, Coleman and Co. Ltd and The Indian Express Ltd. Other multi-crore defamation notices included separate notices sent by Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries Ltd and Anil Ambani-led Reliance Natural Resources Ltd to journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, author of Gas Wars: Crony Capitalism and the Ambanis. The notices were an attempt to remove the self-published book from the website promoting it.

An Inter Press Service story by environmental journalist Keya Acharya on the legal, financial, tax, labour and land problems of the Ramakrishna Karuturi-owned Karuturi Global Limited in Kenya and Ethiopia attracted a Rs 100 crore defamation notice.

Censorship

Censorship showed an overall decrease from 99 instances last year to 86 instances this year. However, censorship in the broadcast media saw an increase to 14 instances, besides five instances of gags on media coverage of sensitive issues being obtained by a range of people, including former judges charged with sexual harassment and sports bodies and educational institutions. A gag on radio jingles by Delhi police was the latest attempt at censorship.

An increase in censorship was also recorded in the arena of literature and non-fiction books, including in academia. In February 2014, Penguin, the publishers of The Hindus: An Alternative Histor, by the well-known Indologist Wendy Doniger, decided to pulp all remaining copies of the book in an out-of-court settlement with Shiksha Bachao Andolan (SBA), which had filed a civil suit against the publishers in 2011.

The organization, headed by Dinanath Batra, targeted other publishers and Orient Blackswan followed suit to withdraw ‘Communalism and Sexual Violence: Ahmedabad since 1969’ by Dr Megha Kumar. The same publisher also put under review Sekhar Bandyopadhyay’s book From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India.

In 2008, SBA was instrumental in filing a complaint before the Delhi High Court seeking the withdrawal of A. K. Ramanujam’s essay, Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translations, from Delhi University’s history syllabus. In July 2014, following the election victory of the BJP, six of Batra’s books were prescribed as compulsory reading as supplementary literature in the Gujarat state curriculum.

Hate speech

Over the last few years, hate speech and hate propaganda have tested the limits to free speech. The Free Speech Tracker has recorded two instances of hate speech in 2012 and ten in 2013. By 2014, the number of hate speech cases doubled, with an additional complaint of hate campaigning.

The death of an innocent software techie, Mohsin Sadiq Shaikh, 24, at the hands of members of a Hindu fundamentalist group, the Hindu Rashtra Sena in Pune on June 4, was a chilling reminder of the violent consequences of hate propaganda. A Facebook post with allegedly derogatory photographs of 17th century Maratha ruler Shivaji and the late Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray had triggered violence in Pune and a mob chanced upon Shaikh and his friend, returning home after offering namaz. Shaikh, who was identified as a Muslim by the skull cap he wore, was beaten to death. Later, seven members of the organization, including its leader, Dhananjay Desai, were arrested and charged with his murder.

Other hate speech cases were recorded throughout the year, beginning with the general election campaign and continuing to the end of the year with a lawyer from Mumbai being charged with posting allegedly inflammatory content on Facebook and BJP MP Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti making offensive remarks on December 3.

Prominent leaders of political parties, including BJP President Amit Shah, were booked for hate speech. Other political leaders charged with hate speech included Pravin Togadia (VHP), Ramdas Kadam (Shiv Sena), Giriraj Singh, Baba Ramdev, Tapas Pal (Trinamool Congress), Azam Khan (Samajwadi Party), Pramod Mutalik (Sri Ram Sene), Imran Masood and Amaresh Mishra (Congress-I).

Contempt, privacy and surveillance

Contempt cases continued to come up and three instances were recorded, including one case that cited the archaic provision of ‘scandalising the court.

Instances of privacy also continued to figure on the Free Speech Tracker as business people and social activists cited privacy concerns to stall books and films based on their lives. In the latter category, Gulabi Gang founder Sampat Pal sought a stay on a Bollywood feature film based on her life on the grounds of privacy and copyright but settled out of court. And the Bombay High Court directed the makers of a film based on the Khairlanji massacre to apply for a fresh certificate from the Central Board of Film Certification.

Surveillance, a growing issue both globally and nationally, remained a concern as the new government reiterated its plans to go ahead with the UPA’s controversial UID scheme even as it quietly continued the roll out of the surveillance programmes of the previous regime.

For a detailed list of the instances from the Free Speech Tracker, please click here.

This article was originally posted on 16 Dec 2014 at thehoot.org and is posted here with permission.

18 Dec 14 | Campaigns, Statements

Sony’s decision to pull U.S. film The Interview from distribution after threats underlines the continuing trend of failure to protect artistic freedom of expression.

“Clearly this sets an example for other anonymous groups to put a curb on artistic expression through threats. This opens the door for anyone to level a threat against artistic works that they don’t agree with or find distasteful,” Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine said.

Sony’s decision to postpone the film on the basis of public safety follows what the company calls an “unprecedented” assault by hackers on its business and employees. The film’s derailing comes as the main North American theatre chains halted plans to show the release amid hackers’ warnings to the public to stay away.

“Sony should take steps to stand up for the free expression of its filmmakers by reconsidering its decision or releasing the film online,” Jolley said.

18 Dec 14 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

A makeshift shrine remembers the Ukrainians killed during protests on Maidan Nezalezhnosti. (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

“There is no civil war in Ukraine. It is a war between Russia and Ukraine, and it is inspired by heavy Russian propaganda,” says Volodymyr Parasyuk as we sit in a café on the main square of the regional capital Lviv in western Ukraine.

This year Parasyuk became a national hero in his country. Some say he changed history when he made a passionate speech on Maidan Nezalezhnosti in Kiev on 21 February 2014, after the police killed about 100 protesters. Parasyuk, head of a sotnia, a unit of 100 men, and part of the protesters’ defence force, demanded President Yanukovich resign and said otherwise protesters would launch an armed attack. The next day the head of state fled the country, and there was a new government formed in Ukraine.

Parasyuk knows what he is saying about war. He joined a voluntary battalion of Ukrainian forces and fought separatists in the east of his country during the summer and autumn. He was wounded and spent a couple of days in detention, but managed to escape.

“This is direct aggression by the Kremlin against my country. This war is completely directed from Russia. We do not have internal reasons to fight each other, the conflict is provoked by lies and propaganda that come from the east,” says Parasyuk.

Statues near Maidan Nezalezhnosti celebrate the friendship between Russia and the Ukraine. (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

To read the full article, subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine or download the app, get 25% off print orders until 31 Dec 2014.

This excerpt was posted on 18 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

18 Dec 14 | News and features, Turkey

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Photo: Philip Janek / Demotix)

What’s wrong with Turkey? Or, more to the point what is wrong with Turkey’s president that makes him so determined to fight, like a two a.m. drunk vowing to take on all comers?

In the past week alone, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his allies have launched attacks on his former ally Fethullah Gülen and his followers, novelists Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak, and even supporters of Istanbul soccer club Besiktas. It would be foolish to attempt to rank these attacks in terms of importance or urgency, but the attack on the Gülenites is the most interesting.

The Gülen movement was almost unknown to anyone outside Turkey and the Turkish diaspora until 2008, when Fethullah Gülen topped an online poll run jointly by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines. The poll was almost certainly hijacked by members of the movement, which its leader modestly claims doesn’t really exist (“[S]ome people may regard my views well and show respect to me, and I hope they have not deceived themselves in doing so,” Gülen conceded in an interview with Foreign Policy. “Some people think that I am a leader of a movement. Some think that there is a central organization responsible for all the institutions they wrongly think affiliated with me. They ignore the zeal of many to serve humanity and to gain God’s good pleasure in doing so.”)

The movement, known to some as “Hizmet”, is seen as bearing great power in Turkey. In a country well used to conspiracy theories about secret organisations — such as the perceived ultra-nationalist, ultra-secular Ergenekon — it is unsurprising that the Gülenists attract suspicion. Their cultishness does little to allay that sentiment.

Among the many weapons at the disposal of the movement are its newspapers, the Turkish Zaman and English-language Today’s Zaman. It was journalists from Zaman, among others perceived as Gülenites, who were arrested over the weekend, as reported by Index.

The move by Erdoğan against Gülenists is widely seen as part of Erdoğan’s defence against allegations of corruption within his party — allegations he believes are led by Gülenists within the police and other agencies.

With their journalists arrested, the Gülenists now find themselves facing the kind of censorship they themselves espoused not so long ago.

In 2011, journalist Ahmet Sik was working on a book called Army of the Imam, which was sought to expose the Gülenists’ connections with the police. The manuscript was seized by authorities. When Andrew Finkel, then a columnist with Today’s Zaman (and occasional Index contributor), submitted an article suggesting that the Gülen movement should not support such censorship, he was sacked by the paper. (The column subsequently appeared in rival English-language newspaper Hurriyet Daily News)

It’s tempting amid all this to wish for a plague on all their houses. But as one Turkey watcher pointed out to me, it’s inevitable that some innocents will get caught in the crossfire between the former allies in Erdoğan’s Islamist AK party and the Gülen movement.

Meanwhile, in keeping with the paranoid style of Turkish politics, pro-Erdoğan newspaper Takvim identified an external enemy in the shape of an “international literature lobby”.

The agents of that lobby, which is clearly anti-Turkish rather than pro-free speech, were identified as Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak. It is, in its own way, true that Shafak and Pamuk are part of the international literature lobby: London-based Shafak can often be seen at English PEN events, and Pamuk has long been identified as a literary and free speech hero around the world. But it is an enormous stretch to imagine that the novelists of the world are gathering in smoke-filled rooms plotting the overthrow of the Turkish state, rather than just hoping that Turkish people should be allowed write and read books in peace. Takvim went as far as to imagine that the authors were paid agents of the “literature lobby”, which is to make the terrible mistake of imagining there’s money in free speech. No matter: paranoia excels at inventing its own truths.

Amidst all this, less glamorous than Pamuk and Shafak, less powerful than Gülen and Erdoğan, fans of Besiktas football club too face persecution. The “Çarşı” group are claimed to have attempted a coup against the government after playing a prominent role in the Gezi park protests. Supporters of the tough working class Istanbul club, known as the Black Eagles, have a reputation for anti-authoritarianism and political activism. According to Euronews’ Bora Bayraktar: “While the court’s verdict is uncertain, what is known is that the Çarşı fans – often proud to be ahead of their rivals – have become the first football supporters’ group to be accused of an attempted coup.”

A source in Istanbul tells Index that when asked how he answered to the charge of fomenting a coup, one accused supporter replied: “If we’re that strong we would make Beşiktaş the champions!”, a prospect as unlikely for the underdog club as a dull but functioning liberal democracy seems for Turkey.

This article was posted on 18 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

17 Dec 14 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Packed inside this issue, are; an interview with fantasy writer Neil Gaiman; new cartoons from South America drawn especially for this magazine by Bonil and Rayma; new poetry from Australia; and the first ever English translation of Hanoch Levin’s Diary of a Censor; plus articles from Turkey, South Africa, South Korea, Russia and Ukraine.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Also in this issue, authors from around the world including The Observer’s Robert McCrum, Turkish novelist Elif Shafak, and Nobel nominee Rita El Khayat consider which clauses they would draft into a 21st century version of the Magna Carta. This collaboration kicks off a special report Drafting Freedom To Last: The Magna Carta’s Past and Present Influences.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”62427″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Also inside: from Mexico a review of its constitution and its flawed justice system and Turkish novelist Kaya Genç looks at recent intimidation of women writers in Turkey.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: DRAFTING FREEDOM TO LAST” css=”.vc_custom_1483550985652{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The Magna Carta’s past and present influences

1215 and all that – John Crace writes a digested Magna Carta

Stripsearch cartoon – Martin Rowson imagines a shock twist for King John

Battle royal – Mark Fenn on Thailand’s harsh crackdown on critics of the monarchy

Land and freedom? – Ritu Menon writes about Indian women gaining power through property

Give me liberty – Peter Kellner on democracy’s debt to the Magna Carta

Constitutionally challenged – Duncan Tucker reports on Mexico’s struggle with state power

Courting disapproval – Shahira Amin on Egypt’s declining justice as the anniversary of the military takeover approaches

Digging into the power system – Sue Branford reports on the growth of indigenous movements in Ecuador and Bolivia

Critical role – Natasha Joseph on how South African justice deals with witchcraft claims

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Brave new war – Andrei Aliaksandrau reports on the information war between Russia and Ukraine

Propaganda war obscures Russian soldiers’ deaths – Helen Womack writes about reports of secret burials

Azeri attack – Rebecca Vincent reports on how writers and artists face prison in Azerbaijan

The political is personal – Arzu Geybullayeva, Azerbaijani journalist, speaks out on the pressures

Really good omens – Martin Rowson interviews fantasy writer Neil Gaiman, listen to our podcast

Police (in)action – Simon Callow argues that authorities should protect staging of controversial plays

Drawing fire – Rayma and Bonil, South American cartoonists’ battle with censorship

Thoughts policed – Max Wind-Cowie writes about a climate where politicians fear to speak their mind

Media under siege or a freer press? – Vicky Baker interviews Argentina’s media defender

Turkey’s “treacherous” women journalists – Kaya Genç writes about dangerous times for female reporters, watch a short video interview

Dark arts – Nargis Tashpulatova talks to three Uzbek artists who speak out on state constraints

Talk is cheap – Steven Borowiec on state control of South Korea’s instant messaging app

Fear of faith – Jemimah Steinfeld looks at a year of persecution for China’s Christians

Time travel to web of the past and future – Mike Godwin’s internet predictions revisited, two decades on

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Language lessons – Chen Xiwo writes about how Chinese authors worldwide must not ignore readers at home

Spirit unleashed – Diane Fahey, poetry inspired by an asylum seeker’s tragedy

Diary unlocked – Hanoch Levin’s short story is translated into English for the first time

Oz on trial – John Kinsella, poems on Australia’s “new era of censorship”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Jodie Ginsberg writes about the power of noise in the fight against censorship

Index around the world – Aimée Hamilton gives an update on Index on Censorship’s work

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Humour on record – Vicky Baker on why parody videos need to be protected

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Dec 14 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

“An attack on women journalists is an attack on freedom,” says novelist Kaya Genç, in a short video interview ahead of the publication of his article on the intimidation of women journalists in Turkey in the latest Index on Censorship magazine.

Genç’s comments come as the country has been gripped by a crackdown on opposition and members of the media.

Genç, a Turkish novelist based in Istanbul, is a contributing editor to Index on Censorship magazine.

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine by Dec 31, 2014 for 25% off a print subscription.

This article was posted on 17 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Dec 14 | About Index, Campaigns, Statements

Index on Censorship joins the net neutrality coalition, a global coalition of organisations and users who believe that the open internet has enabled countless advances in technology, health, education and business, and that it must remain open for all.

Today, the open internet is endangered by powerful service providers seeking to become gatekeepers who decide how users can access part of the internet.

We believe that we have to enshrine net neutrality into law so that the internet remains a platform for free expression and innovation.

“A free and open internet is vital for free expression,” said Index Chief Executive Jodie Ginsberg. “We must defend net neutrality to ensure everyone has equal access to the channels that have become crucial to so much of modern information exchange.”

Join us and find out more at http://www.thisisnetneutrality.org/

Watch the video below on how net neutrality works:

15 Dec 14 | Awards, News and features, Turkey

Şanar Yurdatapan is a songwriter and composer who campaigns for freedom of expression, particularly against the prosecution of publishers in his home country, Turkey.

Yurdatapan won the 2002 Index award for Circumvention of Censorship, to his amusement this was the same year former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi won the award for Services to Censorship.

In 2013, Yurdatapan and Index met at the IFEX General Meeting and Strategy Conference, which he attended on behalf of Initiative for Freedom of Expression; he talked to Index about the Gezi Park protests which were going on at the time. Now, Yurdatapan speaks about the positive effects of international recognition.

Explore the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards

This article was posted on 15 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org