17 Sep 14 | Bahrain, United Kingdom

Nabeel Rajab, president of the 2012 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Advocacy award winning Bahrain Center for Human Rights, discusses the human rights situation in his country during a meeting.

Sept 6, 2014. Protesters outside 10 Downing Street called for the release of Bahraini human rights defenders from detention. Sayed Ahmed Al Wadaei called on the UK to break its silence on the detention of Maryam al-Khawaja, a Danish citizen, in Bahrain.

17 Sep 14 | Artistic Freedom, Index Arts, News and features, Religion and Culture, Turkey

Meltem Arikan is a Turkish playwright living in the United Kingdom.

“Oh, but of course,

you women have the right to speak!

Oh, but of course,

you have the right to laugh!

Oh, but of course,

you have a say over your bodies…

Oh, but of course,

freedom of expression!”

So they say, but in Turkey,

silence grows daily ever heavier

as the culture of fear expands.

If I shout ‘enough’,

will anyone hear my voice?

My voice…

a woman’s voice…

Aren’t women’s voices equivalent to muteness in Turkey?

As women begin to step outside the frames of their lives,

as modern tools for communication enlighten them about the world beyond,

the more curious they become

the more they inquire

the more they change

the more they demand more from their lives.

They dare to say no,

And they become those dangerous women

who are attempting to break the order…

Women, forced into passivity

scared to be counted as trouble makers,

they must be content to accept

the scraps thrown from men’s tables.

The traditional culture engenders fear

the fear of failure:

failing to satisfy the expanding demands of women

men lose self confidence,

when their constructed masculinity is perceived to be at risk,

they will stoop to violence and kill women and children.

So there are men

who feel that their manhood is under threat,

who take issue with their wives’ increasing demands,

who applaud this authoritarian system of government

as an example of how to deal with these problems.

Authority approves violence towards women,

the young and lesbian,

gay, bisexual and transgender people

by extending clemency to perpetrators of violence

instead of punishing them with the severity they deserve.

So there are men

Who are afraid facing up to their fear and pain.

Recoiling from pain and embarrassment of what has happened to them, rebound towards leaders

who apportion them so called high ideals.

So these men have become as dishonorable as the ones

who govern the country through fear and oppression.

Leaving aside, for the moment,

their antagonism towards organized resistance and protest,

just think: they can’t bear you,

the individual woman,

expressing your feelings

beyond the limitations they’ve decreed.

They can’t control their desire to destroy those

who raise their voices

who show resistance to their flawed dominance.

They’re always on the look-out for

the ‘other’,

an individual

or a group:

a race,

a sect

or a religion

on whom to project their hatred

and take revenge.

To mitigate their pain,

they target women,

the young:

anyone

or anything

that reminds them of their own inadequacies

and limitations.

Oppression first manifests in discourse…

Women are should have three children…

Women unveiled are like houses without curtains,

for rent or sale…

Women confirm that women who are raped

are at fault for wearing low cut dress.

It must be true: it’s reported in the press.

Women should not laugh in public.

Girls and boys must be educated separate.

No matter how much they want,

women can no longer shout out loud.

Enough is enough?

They cannot do it.

Shouting? Forget it!

Any female expression results in accusations,

exclusion and irreversible judgments.

If despite this

a woman insists on speaking her thoughts,

she will get a violent response

or at its extreme,

homicidal.

Perpetrate a greater violence

by politicking over women bodies

A genuine course of action against violence

would entail taking

their hands,

their politics

their ideas off women.

If I shout ‘enough’,

will anyone hear my voice?

My voice…

a woman’s voice…

Aren’t women’s voices equivalent to muteness in Turkey?

This poem was published on Wednesday Sept 17 at indexoncensorship.org

17 Sep 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News

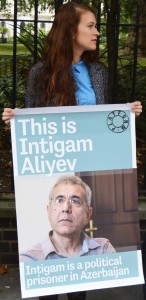

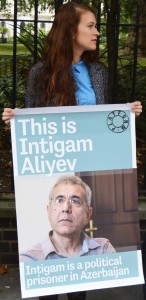

Protest outside BP HQ in London (Photo: Dave Coscia)

Protesters called on global oil giant BP to reassess its connections with the regime in Azerbaijan at a gathering outside the company’s London headquarters.

This week marks the anniversary of the signing of the Contract of the Century, when BP began its 20 year relationship with the Aliyev family. The protesters argue that BP’s role in Azerbaijan has provided the former president, Heydar Aliyev, and the current president, his son Ilham, with considerable power and money, facilitating the country’s repressive regime and hampering democracy.

Claire James – Campaign against Climate Change (Photo: Dave Coscia)

There are currently 98 political prisoners being held in Azerbaijan and the threat of arrest others is also high. Recently, prominent activists Leyla and Arif Yunus and Rasul Jafarov have been jailed, as well as human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev.

Ramute Remezaite, a human rights lawyer who worked in Azerbaijan, told Index on Censorship: “It’s very important to tell BP that it is totally intolerable to cooperate with the government of Azerbaijan, it’s repressing its own people and putting them to prison for reasons such as exercising their fundamental human rights.

Ramute Remezaite – Human rights lawyer (Photo: Dave Coscia)

“Another reason why it’s very important to be here and to hold this action, is as solidarity with our colleagues in Baku because such an action is impossible these days in Azerbaijan — people standing in front of the BP office in Baku would be immediately arrested and sentenced to one, two, three weeks in prison.”

A group of Azerbaijani civil society organisations plan to send a letter to Bob Dudley, group chief executive of BP, demanding that the company call on the Aliyev government to release all political prisoners, and ensure that other prominent human rights defenders, such as Emin Huseynov, will not face arrest.

Emma Hughes from Platform London, who organised today’s protest, told Index: “We’re here today in solidarity with Azerbaijani civil society who are calling on BP to raise the case of the 98 political prisoners in Azerbaijan and also to drop their sponsorship of the 2015 Baku European Olympic Games.”

Also attending the protest, alongside Platform London and Index on Censorship, were representatives from Campaign Against Climate Change, Article 19 and BP or not BP.

Emma Hughes – Platform London (Photo: Dave Coscia)

Claire James, from Campaign Against Climate Change, told Index: “I’m here partly in solidarity with political prisoners but also because our world’s addiction to fossil fuels is overcoming any common sense about what we’re doing to the planet and it should not also be overcoming human rights.”

In conclusion to the letter, Azerbaijani civil society asks that BP ceases its activities in the country until such times as a “democratic and accountable government is in power”.

This article was posted on 17 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Sep 14 | Magazine, Volume 43.03 Autumn 2014

Index on Censorship autumn magazine

In the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine, don’t miss: Burmese-born author Wendy Law-Yone on the challenges the Burma’s media face in the run-up to the next election; TV journalist Samira Ahmed on how television channels should respond to viewers’ complaints; award-winning foreign correspondent Iona Craig reports from Yemen on threats to journalism in conflict zones; plus a brand new short story from playwright and author Ariel Dorfman.

While debates on the future of the media tend to focus solely on new technology and downward financial pressures, we ask: will the public end up knowing more or less? Will citizen journalists bring us in-depth investigations? Will crowd fact-checking take over from journalists doing research? Who will hold power to account? The subject is tackled from all angles, from our writers from across the globe.

Also writing for this issue are Australia’s race commissioner Tim Soutphommasane; human rights lawyer Tamsin Allen on defamation; and novelist Kaya Genc. From South Korea Steven Borowiec talks to controversial artist Lee Ha, and in London political editor Ian Dunt walks the corridors of political power in the UK’s Houses of Parliament and asks if journalists there get too close to government.

Other articles include:

- African digital journalism by Ray Joseph

- Generation why by Ian Hargreaves

- Funding news freedom by Glenda Nevill

You can buy the print version magazine or subscribe for £31 per year here, or download a digital version for your iPad for just £1.79. All subscriptions help fund Index’s work, protecting freedom of expression worldwide.

Read about our magazine launch at the Frontline Club on 22 October.

FULL CONTENTS: ISSUE 43, 3 – The future of journalism

Back to the future: Iona Craig on journalists trying to stay safe in war zones

Digital detectives: Ray Joseph on the new technology helping Africa’s journalists investigate

Re-writing the future: Five young journalists talk on their hopes and fears for the profession – from Yemen, India, South Africa, Germany and the Czech Republic

Attack on ambition: Dina Meza on a Honduran generation ground down by fear

Stripsearch cartoon: Martin Rowson envisages an investigative reporter meeting Deep Throat

Generation why: Ian Hargreaves asks on how the powerful may or may not be held to account in the future

Making waves: Helen Womack reports from Russia on the radio station standing up for free media

Switched on and off: US journalist Debora Halpern Wenger on TV’s power shift from news producers to news consumers

TV news will reinvent itself (again): Taylor Walker interviews a veteran TV reporter on the changes ahead

Right to reply: Samira Ahmed on how the BBC tackles viewers’ criticism

Readers as editors: Stephen Pritchard on how news ombundsmen create transparency

Lobby matters: Political reporter Ian Dunt on the push/pull of journalists and politicians inside Britain’s corridors of power

Funding news freedom: Glenda Nevill looks at innovative ways to pay for reporting

Print running: Will Gore on how newspapers innovate for new audiences

Paper chase: Luis Carlos Díaz on overcoming Venezuela’s newsprint shortage

IN FOCUS

Free thinking? Australia’s race commissioner Tim Soutphommasane on bigotry

Guarding the guards: Jemimiah Steinfeld on China’s human rights lawyers becoming targets

Taking down the critics: Irene Caselli investigates allegations that Ecuador’s government is silencing social media users

Maid equal in Brazil: Claire Rigby on the Twitter feed giving voice to abuse of domestic workers in Brazil

Home truths in the Gulf: Georgia Lewis on how UAE maids fear speaking out on maltreatment

Text messaging: Indian school books are getting “Hinduised”, reports Siddarth Narrain from India

We have to fight for what we want: our editor, Rachael Jolley, interviews the OSCE’s Dunja Mijatovic on 20 years championing free speech

Decoding defamation: Lesley Phippen’s need-to-know guide for journalists

A hard act to follow: Tamsin Allen gives a lawyer’s take on Britain’s libel reforms

Walls divide: Jemimah Steinfeld speaks to Chinese author Xiaolu Guo about a life of censorship

Taking a pop: Steven Borowiec profiles controversial South Korean artist Lee Ha

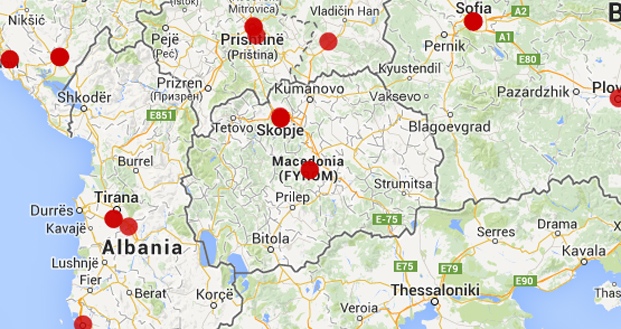

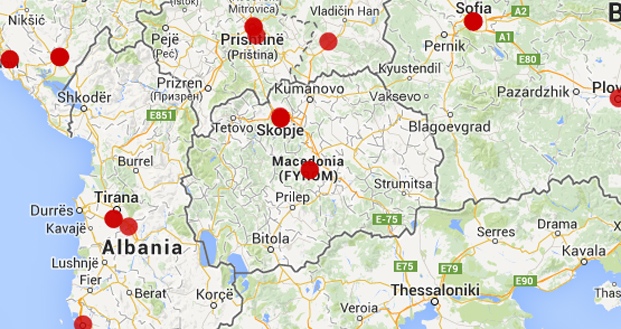

Mapping media threats: Melody Patry and Milana Knezevic look at rising attacks on journalists in the Balkans

Holed up in Harare: Index’s contributing editor Natasha Joseph reports from southern Africa on the dangers of reporting in Zimbabwe

Burma’s “new” media face threats and attack: Burma-born author Wendy Law-Yone looks at news in the run up to the impending elections

Head to head: Sascha Feuchert and Charlotte Knobloch debate whether Mein Kampf should be published

CULTURE

Political framing: Kaya Genç interviews radical Turkish artist, Kutlug Ataman

Action drama: Julia Farrington on Belarus Free Theatre and the upcoming Belarus election

Casting away: Ariel Dorfman, a new short story by the acclaimed human rights writer

ALSO

Index around the world: Alice Kirkland gives a news update on Index’s global projects

From the factory floor: Vicky Baker on listening to the world’s garment workers via new technology

16 Sep 14 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Netherlands, News and features

Journalist Richeron Balentien woke up one night to find his car had been torched (Photo: Richeron Balentien)

It’s a Wednesday morning in May 2014, around 3am and still dark outside. Radio journalist Richeron Balentien, his girlfriend and their 2-year-old daughter are sound asleep until the smell of fire wakes them up. When they look out of the window they see Balentien’s car burning in the yard in front of the house. He immediately knows what is going on.

“It was a clear threat,” Balentien told Index on Censorship over the phone. “It was a warning, to shut me up.” The police confirmed the car was purposely set alight. The perpetrator has not been brought to justice.

The Netherlands is always found near the top of press freedom rankings, this year second only to Finland in the Reporters Without Border’s Press Freedom Index. But rarely taken into account, however, are the Dutch islands in the Caribbean sea. The largest of these, Curacao, became a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 2010.

If Curacao was included in the Netherlands’ press freedom score, it might not place so high on the list. Journalists like Balentien face threats and attacks, as they fight a lonely and dangerous battle to get the truth about corruption and organised crime on the island out.

The attack on Balentien’s car happened just a few hours after Gerrit Schotte, the first prime minister of an autonomous Curacao, was arrested on allegations of money laundering and forgery during his time on power. He was released after a week in custody, but the investigation is ongoing.

Balentien aired the news on his radio station Radio Direct, while many other media outlets kept silent. “This is a small island,” he said. “Everybody knows each other. Most journalists don’t investigate. They don’t want to get into trouble”.

According to a recently published Unesco report, Curacao’s media are “not able to fulfil their role as watchdog of authorities and other powerful stakeholders in society”. It also highlights issues around journalist safety, stating that “some recent cases of harassment of journalists have caused public debate on the issue of safety and are reason for concern”.

The report concludes that social and political pressures lead to self censorship among the press, as “dependency on good relationships with sources of information on one hand and protection of relatives on the other hand is very much a threat”.

In May 2013 the island was shocked by a political murder. Helmin Wiels, a popular politician determined to rid the island of high level corruption, was shot dead by an assassin in broad daylight.

The atmosphere on the island has been tense ever since, Balentien said. “Nobody thought it was possible that someone of that calibre could get killed. It shocked the entire island,” he explained. “The atmosphere changed. Everyone is afraid.”

Two men were sentenced to life in prison for killing Wiels, but it’s still unclear who gave the orders. Many believe they came from high up. There has been speculation that former Prime Minister Schotte knew about the plan, said Balentien — something Schotte himself denies. Wiels had accused the state telecommunications company of involvement in illegal sales of lottery tickets.

The Wiels case is one of Balentien’s ongoing investigations. “I feel everything is being done to keep the truth about this murder behind closed doors,” he said. “We need to know who gave the orders.”

A 2013 Transparency International study shows “a general lack of trust in key institutions” in Curacao. The anti-corruption watchdog labels this “a major obstacle” which will “limit the success of any programme addressing corruption and promoting good governance”. As for the media, the report highlights the lack of trained journalists, with content open to influence by the private financiers and advertisers on which “many media companies are heavily dependent”. Few requirements to ensure the integrity of media employees also “undermines the independence and accountability of the media,” according to the group.

Balentien is sure that former prime minister Schotte gave the order to attack his car. “Sources told me that it was discussed within the party to set my car alight to frighten me,” he said. “I have never been afraid to talk about Schotte, his party or the corruption.”

Dick Drayer, the Curacao correspondent for the Dutch national broadcaster NOS, also believes there was a political motive behind the attack. “Schotte’s party is behind this, everybody knows that,” he told Index on Censorship.

Drayer has been working as a journalist on the island for nearly ten years. “I see is an increase of intimidation towards journalists. Journalists here are taught not to ask questions. There is verbal and physical violence. When you dig in dirty business in Curacao, you know you can get into trouble. That leads to self censorship,” he said. “In Netherlands the media controls the power, in Curacao it’s the other way around.”

While the island has had its own government since 2010, ties with the Netherlands are still strong. Corruption and organised crime in Curacao are occasionally discussed in Dutch parliament and the Dutch police is involved in the Wiels murder investigation.

But “the relationship is disturbed,” according to Dryer. “The Netherlands is careful to intervene when things are going the wrong way on the islands, because they’re afraid to be seen as the coloniser.” He thinks his country could be more involved when it comes to corruption and organised crime. “They should speak up more. The Netherlands worries about human rights in China, but when it comes to Curacao they say it’s an internal matter.”

After the car incident, Balentien’s station Radio Direct continued to receive anonymous phone threats. “I am aware,” he said. “I look around. I turn to see who’s driving behind me. I check my house before I enter.”

Despite this, he maintains he will keep up his investigative reporting on high level corruption and the Wiels murder case.”Because I don’t want this island to be ruined by these people anymore”.

More reports from The Netherlands via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Bloemendaal municipality accused of censoring local newspaper

Journalists attacked during anti-ISIS protest in The Hague

Journalist on trial for defamation

Photographer assaulted by housing corporation employee

Restrictions on filming inside parliament building

This article was posted on 16 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Sep 14 | Germany, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society

Vandals attacked the Lausitzer Rundschaufor the second time in a week.

On the night of September 4-5, the daily newspaper Lausitzer Rundschau became victim to a crime by now familiar to its employees: neo-nazis vandalised the outside of one of its office buildings in the eastern German city of Spremberg, covering it with anti-Semitic graffiti. Less than a week later, on the night of September 8-9, another Lausitzer Rundschau office in the nearby city of Lübbenau faced a similar attack.

The incidents were covered by national and local media in Brandenburg, the state surrounding Berlin. Right-wing extremism has been a sensitive topic for the Lausitzer Rundschau—only two years ago, the newspaper’s Spremberg office was also vandalized by neo-Nazis who left graffiti and an animal carcass outside the building. Shortly before the 2012 attack, the newspaper had reported critically about a right-wing extremist march in Spremberg.

Klaus Minhardt, president of the German Journalists’ Association’s local Berlin-Brandenburg chapter, sees offences like the ones against Lausitzer Rundschau as motivated by a small group of individuals lashing out against specific media reports.

“People like to make journalists their victims and to take revenge out on them. Usually, somebody does something bad and the journalist who uncovers that becomes the face of the issue,” Minhardt said.

A few days before the September 4 attack, Lausitzer Rundschau ran a report on a trial in the nearby city of Cottbus, where police testified that right-wing extremist paraphernalia was found on an alleged assailant’s body. Johannes M. Fischer, editor in chief of Lausitzer Rundschau, says the newspaper’s reporting on the trial is one reason for the recent vandalism. Another, says Fischer, is the upcoming Brandenburg state elections on September 14. Election posters in the area surrounding Lausitzer Rundschau’s offices were also covered in anti-Semitic graffiti after both of the new incidents.

This past week’s attacks on the newspaper were shocking because they were repeated in quick succession. According to Fischer, the kind of vandalisation was also more brutal than the previous incident in 2012.

“The quality is different. It has a horrible quality. The sayings are more violent. ‘Jews, Jews out, gas Jews,’ which was abbreviated as VE.G.,” Fischer said.

Because of the proximity between the two offices in Lübbenau and Spremberg, police have said that the same people are likely responsible for both of the September attacks on Lausitzer Rundschau. Fischer is also convinced that a only a few dozen people are behind the vandalisation, and he stresses that the Lausitz region is tolerant, while locals have expressed support for the newspaper after the attacks.

Lausitzer Rundschau has become well known for its aggressive reporting on neo-nazi activity in the region, which covers parts of the eastern German states of Brandenburg and Saxony. In 2013, two of the newspaper’s reporters won national prizes for their work on right-wing extremists in the area.

The “tough staff,” Fischer says, is not intimidated by the attacks on their offices and is determined to continue covering neo-nazi groups there. Fischer still refers to the vandalisation as a threat, and says he has offered reporters various options if they feel uncomfortable working after the attacks.

“They could switch to a different beat. And we also said, ‘You don’t have to write about this topic,’” Fischer said.

None of the Lausitzer Rundschau journalists took Fischer up on that offer. He adds, “They say, ‘Now we really have to do this.’”

More reports from Germany via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com:

Deutsche Welle accused of censorship

Public broadcaster fires blogger

Photographer arrested at protest

ECHR rules court decision to stop publication about Chancellor Schröder was illegal

Head of state chancellery intimidates journalists with legal warning

This article was published on Monday Sept 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Sep 14 | European Union, News and features, United Kingdom

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) filed an application on Friday with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg challenging current UK legislation on mass surveillance and its threat to journalism.

Lawyers Gavin Millar QC at Doughty Street Chambers, Conor McCarthy at Monckton Chambers and Rosa Curling at Leigh Day solicitors have been assisting the BIJ with its investigation. The group argues that UK legislation imposes constraints on journalistic free expression and does not offer enough protection for journalists’ sources, therefore it is in breach of Articles 8 and 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR).

Information uncovered by American whistleblower Edward Snowden appears to highlight how developments in mass surveillance could pose a major threat to the process of journalism. Rules for the interception of data are set out in the Regulation of Investigative Powers Act (RIPA), however, this act does not offer enough controls or checks for external communications. Therefore, any information exchanged through services such as Gmail, Google Docs and Dropbox may not offer the level of confidentiality expected, the group wrote in their application to the ECHR.

It is not only communications which may be scrutinised by the government or secret services; they also have access to metadata, which is the data generated as you use technology. It includes information such as the date and time of phone calls and where emails are sent from. Metadata can be linked to sophisticated computer programs which can enable the user to collate masses of information, building an intricate picture of an individual or organisation’s movements, contacts, sources and lines of enquiry.

According to BIJ, the main implication of unregulated mass surveillance is that journalists can no longer offer anonymity to their sources, or assume that their work is confidential until publication.

This is further compounded by the number of the situations where it is deemed appropriate for surveillance techniques to be enlisted are vaguely defined within the law. It states that data can be intercepted where it is believed that the security or economic interests of the state are involved, meaning investigative journalists especially have to be cautious when covering topics which may be of interest to the government and the intelligence services.

Currently, the BIJ believes the only way in which journalists can be sure they are protected against mass surveillance is to do all of their communications in person, without the use of electronic devices – something which is often impossible, especially if sources are based outside of the UK.

However, under the ECHR journalists should be able to expect protection, the BIJ asserts. At the very least, the group said, this application will spark high-level debate within the government about how journalism and freedom of expression can be protected when governments are using advanced surveillance.

The BIJ says: “In the long term we would like to see proper regulatory control and scrutiny of how the intelligence services use mass surveillance to ensure these techniques and technologies are not being used to hamper legitimate journalistic investigation and inquiry.”

This article was posted on Sept 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Sep 14 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Russia

(Photo: Okras/Wikimedia Commons)

Pity poor Dmitry Dayneko. The Belarusian teen recently completed the ice-bucket challenge, as millions like him have before, and posted the video of himself being drenched in cold water on social media. So far, so hilarious/tedious (depending on your view of the challenge), but, ultimately, quite harmless.

Except apparently it wasn’t. Dmitry and the friends who poured cold water over his head say they were summoned by local authorities and given a stern warning to behave themselves, apparently on the orders of the KGB in Minsk. The reason? Not the icy water itself, but Dmitry’s temerity in nominating Belarus’ president, Alexander Lukashenko, to do the challenge next.

Lukashenko, one feels, is not a man who does lighthearted fun. One cannot imagine him posting a selfie of himself holding a cocktail with an umbrella in it, hashtagged #YOLO. One cannot even begin to think what he’d wear on fancy dress day at Bestival. He’s probably weirdly competitive at bowling. He does not do Wii.

This does not make him an exceptional dictator. In the history of autocrats, I can’t think of a single one who was mainly in it for the laughs, unless it was fun of the crushing your enemies, seeing them driven before you, and hearing the lamentations of their women variety.

In journalist Ben Judah’s recent, acclaimed essay on the court of Vladimir Putin, he describes a lonesome, rigid emotionless figure, whose only apparent joy is ice hockey, which Judah says, Putin finds “graceful and manly and fun”. This is quite normal for a man of his age and geographical situation (Lukashenko has the same love for ice hockey). But there is a difference between “fun” and “funny”; playing sport is fun. It may even be more fun if your opponents are scared of you. What it is not, though, is funny.

Because dictatorships don’t — can’t — do funny. People can make great jokes about authoritarian regimes, certainly. Ben Lewis’s Hammer And Tickle details the jokes that got people through Soviet communism between 1917 and 1989, most of which revel in the jarring, depressing juxtaposition between Soviet promises of milk and honey and everyday reality (“What is the definition of capitalism?” “The exploitation of man by man” “And what is the definition of communism?” “The exact opposite”.)

But those within the regime, within The Party, never, ever find themselves funny, which is why the generals end up with such large hats.

A couple of years ago, a viral video spread of Belarusian soldiers putting on a display on the country’s Independence Day. It was synchronised, controlled, disciplined, and one the campest things I have ever seen — the Red Army choreographed by Busby Berkeley. But this would not for one moment have occurred to anyone in charge.

Funny doesn’t work for dictatorships because funny usually involves humanity, and vulnerability. This is the appeal of the viral ice bucket challenge video: not admiring the superhuman feat of standing still while freezing water cascades over you, but laughing at the apprehension beforehand, and the hopping and shouting and screaming in the moments afterwards.

In the hands of the likes of Putin or Lukashenko and their apparatchiks, the challenge would have to become a real feat of strength and endurance: somehow Vladimir Putin would invent colder iced water than everyone else did, and then have more of it poured on him than anyone thought possible. And it would be boring because he would not flinch. And then he would not nominate anyone else, because, well, where do you go after Vladimir Putin or Alexander Lukashenko? What man could equal such a task?

Andy Warhol once pointed out that in America, an odd consumer egalitarianism existed: “You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola,” the artist said, “and you know that the president drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking.”

The same is true of viral phenomena like the ice bucket challenge, or the Harlem Shake before it (that meme aggravated the Azerbaijaini authorities so much that people were arrested for allegedly taking part in it). There’s no way of making throwing water over someone’s head much more than it is. The Harlem Shake effectively died when people started trying to make slicker or (shudder) sexier versions.

In spite of near-ubiquitous celebrity participation, an ice bucket challenge is an ice bucket challenge is an ice bucket challenge.

In spite of its claim to oversee a “social state” that works “for the sake of the people”, the Soviet nostalgist regime of Lukashenko cannot bear such egalitarianism.

This article was posted on 11 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Sep 14 | Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society

Index on Censorship and Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso are joining forces to map the state of media freedom in Europe. With your participation, we are mapping the violations, threats and limitations that European media professionals, bloggers and citizen journalists face everyday. We are also collecting feedback on what would support journalists in such situations. Help protect media freedom and democracy by contributing to this crowd-sourcing effort.

Journalists have raised concerns over a new round of amendments to Macedonia’s Law on Audio and Audiovisual Media Services (LAAMS).

According to the Association of Journalists of Macedonia, the changes increase the role of the director of the Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services in disciplining media. The government can now also subsidise up to 50% of domestic film production costs for private media.

“We find this problematic because it brings risk that the government will influence even more national media by using public funds to cause certain content to be produced and broadcast. In our opinion this should be banned. Obligatory domestic production should be reduced taking into account its financial implication on the media,” Dragan Sekulovski, executive director of the Association told Index on Censorship.

For its part, the agency claims that the law’s aim is to promote media freedom.

“The suspicion for censorship is ill-founded, since, according to the constitution of the Republic of Macedonia, censorship is forbidden,” Maja Damevska, spokesperson for the agency, told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. “The regulatory body takes care only of proper implementation of the media legislation and therefore has never undertaken a measure or an action that can be considered censorship.”

More reports from Macedonia via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Macedonian Court does not recognise violation of the right to freedom of expression

Macedonian contributor attacked over contribution to Freedom House report

Police officer infringes journalist’s phone data privacy

Telma TV under government pressure

Police pressure journalists during protests in Skopje

This article was posted on Sept 12, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Sep 14 | Draw the Line, Youth Board

Free expression and policing can have an antagonistic relationship. Recent events in Ferguson are demonstrative of the issues that arise as the demands for protest clash with those for civil safety.

The police are naturally drawn to the forefront of such a debate as they become the physical manifestation of a state’s commitment to free expression and the right to protest. Thus, as the Obama administration launches a federal investigation into whether the Missouri police systematically violated the civil rights of protesters, it is prescient to ask whether one can demand more of the police to protect free expression.

Undoubtedly, enforcement agencies across the world play a tricky role in facilitating expression while protecting the legitimate safety concerns of the local community. Between 2009 and 2013, police in England spent £10 million on security arrangements for EDL marches. There can also be a huge social cost to galvanic protest and the director of Faith Matters, Fiyaz Mughal, has called for a ban on such marches, claiming that “[We] know there is a corrosive impact on communities, it creates tensions and anti-Muslim prejudice in areas. I think enough is enough. I think a banning order is necessary with the EDL”.

What the recent altercations in Ferguson illustrates is that the role of the police in safeguarding free expression must not be overlooked. More importantly, this is a global issue and as six activists being retried for breaching Egypt’s protest law have started an open-ended sit-in and hunger strike it must be remembered that this debate truly gets to the heart of the basic demands of any civic society.

As scenes from Ferguson have at times resembled the images of police crackdowns in Cairo it is clear that complacency about such issues can prove disastrous. It therefore seems vital to drawn certain lines as to where we feel the police should stand when it comes to creating the basis of a safe but also free society.

This article was posted on 11 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Sep 14 | Academic Freedom, Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

In May 2014, Egyptian security forces entered a student housing area of Al-Azhar University, during clashes with student protesters in Cairo. (Photo: Ahmed Hendawy /Demotix)

With just a few weeks to go before Egyptian universities open their gates to students for the start of the new academic year, the Egyptian authorities are feeling jittery — and rightly so.

The previous academic year saw an unprecedented wave of violence at universities across the country with clashes between “anti-coup” student-protesters and security forces on an almost daily occurrence that forced the repeated postponement of exams. At least 14 students were killed in the violence, hundreds of others were detained and hundreds more were expelled for organising or taking part in protests, according to Al Ahram.

Ahead of the new academic year, the authorities have taken some new, stringent measures to ensure the past year’s scenario is not repeated. They have also issued stern warnings to students that they will adopt a “zero tolerance approach” towards dissent. Any student who criticises President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi or any “symbol of the state” face repercussions. According to warnings issued last week by two major state universities –Ain Shams and Bani Suef — students who violate university regulations by “defaming public officials” will be subject to an internal disciplinary investigation and risk expulsion.

The announcement drew angry outcries from students and rights advocates who expressed their concern on social media. Critics fear the new regulation would curb the rights to free speech and expression. Since the 3 July ouster of Islamist President Mohamed Morsi by military-backed protests, the Egyptian authorities have imposed sweeping restrictions on freedom of expression. The massive security crackdown on dissent has targeted Islamists, liberal activists , journalists and academics.

A draconian law passed last November bans protests without prior permission from the authorities. Scores of liberal opposition activists including several prominent figures in the January 2011 mass uprising have been imprisoned for protesting against the repressive legislation. Hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters also languish behind bars for staging “anti-coup” protests following the overthrow of Morsi.

In February, an Egyptian court approved the stationing of police forces at universities, overturning a 2010 verdict banning police presence at educational institutions. The Ministry of Interior hailed the latest court decision, saying the police deployment was “necessary” to quell opposition protests led by supporters of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood (designated by Egypt as a terrorist organisation following Morsi’s ouster). The beefed-up security presence at universities has resulted in the arrests of hundreds of students and the deaths and injuries of dozens of others over the course of the past year. Many of the detained students have been sentenced to between 3 and 17 years in jail on charges of staging unauthorised protests, having links to a terror group and inciting violence.

Meanwhile, Minister of Endowments Mokhtar Gomaa has called for a purge of Islamist-leaning deans, staff and faculty members from state universities. The independent Mada Masr quoted Minister Gomaa as saying that universities should be “cleansed of academics sympathetic to the banned terrorist group”. He has also demanded that firm action be taken against the so-called “Academics Against the Coup” — an Islamist partisan group of scholars whose members are purportedly connected Al-Azhar University’s board of directors.

In another restrictive move, Cairo University Head Gaber Nassar has called for the dissolution of student groups or organisations of any political affiliation at all universities. According to Al Youm El Sabe’ newspaper, new students enrolling at universities will now be requested to sign a document pledging not to engage in any political activities on campus.

While the government insists the new measures are part of its ongoing war against terrorism and claims that the upsurge in violence at universities is “an extension of the nationwide Muslim Brotherhood insurgency”, a security source told Index that the ban on student protests goes beyond suppressing the Muslim Brotherhood rebellion. Speaking on condition of anonymity, he said that “the ban is not just aimed at restoring stability”.

“The government wants to spread a culture of submission and fear similar to that which prevailed under Hosni Mubarak. It is trying to instil the idea that the opposition is evil and must be crushed,” he added, warning that “students engaging in political activities will be accused by both the authorities and ‘patriotic’ government supporters of being affiliated to the terrorist group.”

The latest restrictions are a far cry from the period between the 1930s and the 1970s when Egyptian state universities were a hotbed for political activism and the student movement was an instrumental political force in Egyptian society. That ended, however, with amendments introduced to the student charter by late President Anwar Sadat in 1979. The changes “essentially were intended to undermine the power and activism of students on campus by dissolving the representative student bodies,” author Hisham Adawi wrote in his book In Pursuit of Legitimacy published in 2004. While Hosni Mubarak, the authoritarian leader toppled by the 2011 protests, was relatively more tolerant of political expression and dissent than his predecessors Gamal Abdel Nasser and Sadat (at least during the early years of his rule), he too cited fears that “the university’s faculties were becoming strong recruiting points for militants”. Using this as a pretext, he again altered the charter to allow further administrative and security intervention in student activities. Mubarak’s amendments drew criticism from rights advocates who sarcastically called it “the State Security Charter” (in reference to the autocratic leader’s detested security apparatus). Despite sporadic periods of heightened tensions — particularly at Al Azhar and Cairo University — there has since been no true revival of the student movement as an influential political force in society.

Despite the recent warnings by the authorities, angry students staged a small rally outside Cairo University last Wednesday to protest the new measures. The protesters denounced the restrictions, chanted anti-government slogans and demanded the release of their detained colleagues and academics. No fewer than 160 faculty members and staff have been arrested and detained since the July 2013 overthrow of President Morsi, according to an April 2014 report compiled by Egyptian academic rights groups and posted on the Al Jazeera Arabic website. Several academics charged with “supporting the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood” remain at large and have either fled the country or gone into hiding.

Dr. Emad Shahin — an internationally renowned scholar of political Islam who has taught at Harvard, Notre Dame and the American University in Cairo — was charged with espionage in January. He is listed as one of the defendants in a criminal case against several Muslim Brotherhood leaders (including the deposed President Morsi) and stands accused of “conspiring with foreign organisations to undermine Egypt’s national security”. An outspoken critic of the bloody crackdown on Morsi’s supporters after the military takeover, Shahin learnt of the arrest warrant against him while on a visit to Washington nine months ago. He has since remained in the United States and has denied the charges in an email to the New York Times. “The accusations against me are baseless, politically motivated and beyond preposterous,” he said.

Amr Hamzawy, a liberal political scientist and former lawmaker and senior associate at the Carnegie Middle East Centre in Beirut, has also been charged with “insulting the judiciary”. In January, a lawsuit was filed against him by a lawyer after he questioned (on Twitter) a verdict against a group of foreign non-governmental organisations. Hamzawy was released after being investigated for several hours by the public prosecutor.

In a new case that has fuelled concern among rights advocates, Dr. Mohamed Tarek, an adjunct professor at the faculty of science at Alexandria University, was arrested, detained and allegedly tortured last week. He was arrested on 29 August from a street near his home in Alexandria, and has been held in custody since. Police later raided his home and confiscated his laptop and other personal belongings. There have been conflicting reports of his arrest: Interior Ministry sources claim they arrested him during a protest march in Moharram Beik district in Alexandria. Rights groups meanwhile, insist he was detained for giving his testimony of last year’s Raba’a massacre to Human Rights Watch. Tarek was injured in clashes with security forces during the forced dispersal of a sit-in staged by supporters of Morsi outside Raba’a El Adaweya Mosque in the Cairo neighbourhood of Nasr City in August 2013. His chilling account of the forced evacuation featured in a damning report released by Human Rights Watch last month.

According to the 195-page report titled All According to Plan, Egyptian police and the army used “grossly disproportionate and premeditated lethal force against overwhelmingly peaceful opposition protesters” resulting in the killings and injuries of hundreds of them in a single day of violence. The report describes the Raba’a deaths as “likely crimes against humanity” and calls for those responsible to be brought to justice. The Egyptian government has dismissed the report as “politicised” and “biased”. Days after the release of the report, Cairo Airport authorities prevented Human Rights Watch staff members from entering the country, saying the organisation “has no legal status that would allow it to operate in the country”. Human Rights Watch said the move was “an attempt by the Egyptian authorities to gag critics”.

While Egyptian authorities are hoping the new proposed measures will help end violence at state universities, sceptics warn the clampdown on freedoms can only further fuel the unrest. With the new academic year scheduled to begin on October 11 (instead of in late September as originally planned), many worry about a fresh eruption of unrest that may well result in even more bloodshed.

This article was posted on 10 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Sep 14 | Leveson Inquiry, News and features, United Kingdom

“The greatest threat to freedom of the press in our country is our libel law. Why do we have this weird defamation law, where the idea is that if we get something wrong about someone, we have to pay a pile of money? We should correct it with equal prominence. Take money and costs out of the picture. Because, on the whole, only the rich can afford it,” investigative journalist Nick Davies told an audience at the Frontline Club last night.

Davies, who unveiled the extent of the phone-hacking scandal and has just published his book Hack Attack, was in conversation with author and former ITN chief Stewart Purvis (above), talking about hacking, press regulation and this week’s launch of the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso).

Below are some highlights.

On his hacking investigation:

“The crimes weren’t serious enough to spend seven years of your life working on it. What makes it interesting is it’s about power. The thing that Murdoch generates – aside from money and circulation figures – is fear. Once a media mogul has established this kind of fear – he doesn’t have to tell the government, the police or the PCC what to do. They will all try and placate him. That’s really what this book is about and if there is any justification for doing this much work on one story, it’s that.”

On Ipso – which he describes as a “phoney regulator”:

“If Ipso turns out to be subject to the same influences of the big news organisations as its predecessor the PCC, then it is very worrying because Ipso has considerably more power. It has the power to investigate; it has the power to levy fines. You imagine what would have happened if that had been in place when we were investigating phone hacking. They could have killed that story off.”

On the greatest threat to freedom of the press:

“The greatest threat to freedom of the press in our country is our libel law. Why do we have this weird defamation law, where the idea is that if we get something wrong about someone, we have to pay a pile of money? We should correct it with equal prominence. Take money and costs out of the picture. Because, on the whole, only the rich can afford it.”

On whether the truth has caught up with Murdoch, as the book’s subheading suggests:

“There was a moment when the truth caught up with Murdoch – that day in Parliament with his son – but slowly the power comes back. Now he is meeting Nigel Farage [Ukip leader] as if this Australian with American citizenship has any sort of influence at all about what happens in our next election. What is wrong with our system that he is allowed to display such arrogance? We are the voters. It will be interesting to see if in the run up to the 2015 elections he and his newspapers throw their weight around as usual. I fear we will see a familiar pattern, as the bully in the playground.”

On the future of journalism:

“The biggest best hope for journalism is that it continues to attract energetic, bright, idealistic young people. But then you see them being fed into this mincing machine. The key to our revival is fixing the broken business model. We need to find a solution to this problem.”

On the internet:

“[With internet news], you end up with fragmentation. The communist produces news for communists, the racist produces news for racists. Nobody is factchecking, nobody is accountable. It’s much worse, potentially, than the mainstream news organisations that come in for such a kicking. The internet is potentially a very destructive force. I’m not necessarily saying it will go this way, but it could rank up there with nuclear weapons, where you say, ‘Christ, that was clever of us to invent that, but we potentially wish we hadn’t done it’. I just don’t know where it is going to go.”

On citizen journalism:

“In an ideal world, we should have professional journalists. There are too many people on the left whose knee-jerk reaction is to assume that all journalists working for big corporations are corrupt and unable to tell the truth. To dismiss journalists from these organisations going to Syria and Iraq and risking their lives as corporate puppets is really disgusting. There is a belief that if the profession of journalism dies out, we’ll be better off with citizen journalists. Do you want citizen doctors too?”

On who he’d like to play him in the film version of his book (the rights to Hack Attack having just been bought by George Clooney):

Colin Firth

Join us to debate the future of journalism and whether it might lead to democratic deficit at the Frontline Club on October 22, or subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine to read our special report on the future of journalism and whether the public will end up with more knowledge or less.

This article was posted on 10 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org