29 Aug 14 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

Defendants in Egypt’s NGO trial held in cages during proceedings (Image: Al Jazeera English/YouTube)

In an apparent attempt to crackdown on criticism of Egyptian authorities, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the country have been given an extra 45 days (previously, NGOs were given until 2 Sept) to register with the government, or risk being shut down or prosecuted. This action is being taken under the much-criticised Law 84, passed by former president Hosni Mubarak. It allows the government to dissolve organisations, freeze their assets, confiscate their property and block their funding, without judicial review. At the same time a new law concerning NGOs has been proposed, under which activists face 15 years in prison and fines of over £8,000 for activities such as operating without a licence or working with international groups without permission.

Independent groups in Egypt have been targeted by authorities for many years. In 2012, a group of 43 Egyptian and foreign NGO workers were convicted of operating without a licence and receiving foreign funding, in the widely condemned “NGO trial“. Twenty-seven of the defendants were tried in absentia, and have so far avoided serving the five-year sentences handed down to them. But being convicted as an NGO worker in Egypt has consequences far beyond that country’s borders, as Michelle Betz, one of the 27, writes.

—

It was bad enough to learn that I had been indicted by Egypt in the 2012 NGO case but only a short time later my world seemed to collapse around me.

I was in the US Virgin Islands enjoying my first holiday in over a year when I received an unexpected phone call informing me that Egyptian officials had gone to Interpol, the world’s largest international police organisation, asking them to issue red notices on me (and several others) as they considered me a “fugitive” and wanted me to face trial in Cairo; this despite the fact that I had never actually worked in Egypt.

I had no idea what a red notice was or what the implications were, but I quickly learned just how serious this situation was going to be. An email from the head of the NGO for which I had been consulting said: “I just got off the call with the [US] government and I must ask you all to refrain from travel for the time being. Michelle, you are in the US Virgin Islands, so returning home should not be a problem. If you have other travels plans, you need to put them on hold.”

My work in media development and press freedom requires frequent travel around the world. If I couldn’t travel, I couldn’t work. My career came to a screaming halt. I scrambled to find someone to take my place for contracts I was obliged to fill. All the while, I struggled to get my head around the fact that I was “wanted” and considered a “criminal”. The situation soon went from bad to worse. I learned that not only had Egypt requested that Interpol put out a red notice calling for my arrest and extradition from wherever I might be in the world; they also put out a little known, and not frequently discussed, diffusion notice.

Having never been accused of any crimes in my life, I began educating myself on what red notices and diffusions are, the power of Interpol and its member states, and the inability of regular people, such as me, to obtain due process or even receive basic information about their cases.

What I learned shocked me. Member countries of Interpol can unilaterally put out a so-called diffusion notice without any review from Interpol or even the country of citizenship of the alleged criminal. This notice is immediately sent to all subscribers of the Interpol database and puts countries on notice they should hold and seek extradition of the individuals named. I learned that, as in my case, with no review and no due process, this system has reportedly become rife with abuses in harassment of individuals for political crimes.

At that point, my quest to seek answers to legal questions such as extradition, red notices and diffusion became truly farcical. I tried to contact Interpol as the US Justice Department would not answer my questions. Justice said that I had to turn to my “local law enforcement agency” — in this case, Washington, DC Metro Police Department (MPD) — and Interpol does not take calls from individuals. The Interpol website offers no advice or support for those facing difficulties with their system. After speaking to numerous people at MPD, I was finally referred to a nice lady who, although sympathetic, didn’t even know what Interpol was, let alone the who the Interpol liaison at MPD was, if there even was one.

I repeatedly sought clarification from both the US Departments of Justice and State about what would trigger an airport stoppage due to a red notice or diffusion, my rights, who could help me, even on whether getting a new passport would help. I asked if anybody could help me to determine if there were countries I could safety travel to without fear of extradition. These queries were never answered and more than two years later I still await answers.

It is ironic that in a news release dated 23 April 2012, Interpol stated that: “Anyone seeking the truth about Interpol’s involvement, or otherwise, in any matter should contact the organisation directly in order to ascertain the facts, rather than making statements based on ill-founded rumour and speculation.” Of course, the problem is that Interpol will not take calls from individuals (such as myself) to answer questions and ascertain facts.

In the end, apparently some behind the scenes negotiations occurred resulting in a statement by Interpol in which they asked member countries to erase the already issued diffusion notices from their databases. But I have no way of knowing if these notices were removed, how long they might remain active, or even if I am at risk of future diffusions from the Egyptian authorities.

In June 2013, we faced this situation anew as the Egyptian prosecutor publicly stated they will again seek extradition and put out international wanted notices through Interpol after my colleagues and I were given stiff sentences of five years hard labour. This came after being tried in absentia by what many have portrayed as a kangaroo court.

The past two and a half years have been incredibly stressful, mentally exhausting, frustrating and career-destroying in part due to the lack of information available from Interpol concerning my case. There is no accountability of this organisation and its procedures to which the US (and nearly 200 other countries) is a signatory.

Those of us who are being harassed by member states for political purposes, such as in the Egypt NGO case, have no access to due process and there is no transparency. And while our types of case may be a minority of those pursued using the instruments that Interpol provides, our stories need to be heard and the injustice we are facing needs to be addressed. Otherwise Interpol risks being misused as a tool for oppression by authoritarian and corrupt governments.

A version of this article has been published on Fair Trial International.

28 Aug 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features

(Image: Nemanja Cosovic/Shutterstock)

I’m on holiday in Ireland, and taking a break from standing up for people’s rights to misattribute quotes to Voltaire and Orwell. This is what people who normally go on about civil liberties battles do on holiday; we revel in the dark side, and engage in orgies of frightful behaviour. For two weeks in August, defence lawyers who normally fight the good fight lock people in cupboards and throw away the keys; anti-surveillance campaigners retreat to their hides high above the city, and just…watch. Digital rights folks take down physical notes of all your Facebook statuses. I once spent a delightful summer phoning people at random and then telling them to shut up when they answered the phone.

It’s a wonderful release, but for understandable reasons, we don’t talk about it. It’s the prime directive of the League of Sanctimony: what happens in those two weeks in August must remain hidden from the world.

Until now, that is. Having grappled with the crippling irony of concealing the truth from Index on Censorship readers, I have decided that you have a right to know about everything I would have banned without a second thought, if only during the last bit of August. In no particular order, here we go:

Newspaper holiday reading lists. Dear writer/reporter/critic: you’re either lying about all those books you’re going to get through during your delightful few weeks in Tuscany/Cornwall/west Cork/Thorpe Park, or you’re telling the truth and making me feel inadequate.

Rainy holidays: Yes, I know I shouldn’t really complain about going to Ireland and experiencing heavy precipitation. I don’t care. I’m doing it anyway.

People who can’t write (of whom there are many).

People who can write better than I can (of whom there are many).

People who think pointing out split infinitives makes them look clever. It doesn’t. Split infinitives are perfectly fine. Just don’t ask me why.

People who are good at explaining grammar and syntax. See above.

People who are good at explaining grammar and syntax but then end up allowing anything, cheerily proclaiming “The thing is, language is evolving all the time.” For God’s sake, make a commitment, man.

Really terrible internet memes. David Icke, former Coventry City goalkeeper turned conspiracy theory bother no 1, is the master of these. Look at this, for example. It’s just a picture of a man with snarky words written over it. That’s not a meme.

Any article in print or online which sets out to prove that a current conflict proves that the writer was correct in his or her position on a previous conflict. Thanks. Helpful.

LinkedIn. I still don’t understand. Still.

The word “Listicle”. What’s wrong with “list”? Or “article”? I could even be happy with “list article.”

Lists. Hang on…

Defensive articles about why one form of entertainment is EVERY BIT AS VALID as other forms of entertainment. Video games are video games. Comics are comics. Neither are novels. Move on.

Those public service “poems” on the London Underground. They have been sent to torment all right-thinking people. Read this, and despair for all of us.

I could go on, possibly forever. But it wouldn’t matter a damn. No one in their right mind would take me seriously. It’s just the furious venting of a cranky old man, shaking his fists at the clouds. And yet, every day, censors, religious or moral or autocratic, demand to be taken seriously.

They contend that they are uniquely qualified to say what others can and cannot see or hear or read. Worse, they tell us they are censoring for our protection. They can read a blasphemous book, or watch a pornographic film, and decide soberly what effect it will have on society. Whereas if the likes of you and I went near these things, the entire world would be transformed into something resembling Ken Russell’s The Devils in about 15 minutes. They think we’re impressionable. They think we’re gullible. They think we’re children.

As the holidays come to a close and we reluctantly switch our brains back on to face the coming winter, let’s not block out the calls for censorship: that, of course, would be hypocritical. But perhaps we can turn the tables on the cries of the censors, smile politely and continue about our grown-up business.

This article was posted on August 28, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

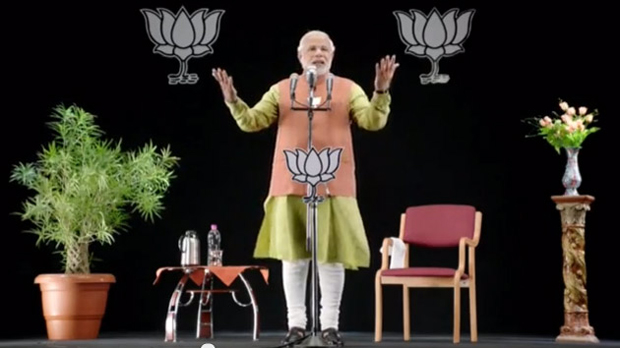

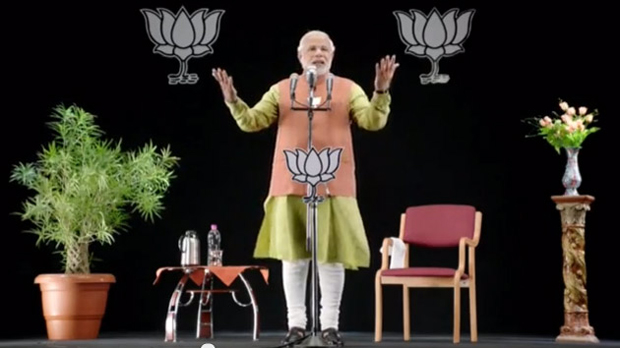

27 Aug 14 | Asia and Pacific, India, News and features

While campaigning to become prime minister, Narendra Modi addressed voters through 3D technology on several occasions (Photo: Narendramodiofficial/Flickr/Creative Commons)

Indians don’t usually take much notice of the prime minister’ speech on independence day in the middle of August. This year was different. This year there was so much discussion on social media that it became a trending topic.

In contrast to the way other prime ministers have handled this moment, new Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), wowed a large section of Indian society not just with what he said, but the way he said it. People are gushing over the fact that he spoke without notes, and did not use the usual bulletproof glass. Others are impressed with the content; he touched upon topics as diverse as rape, sanitation, manufacturing, and nation building, using easily accessible language. Modi is also using social media to get his views across direct to the public, and bypassing the mainstream media.

This straight-talking style only adds to Modi’s brand, but he is also attracting criticism from the mainstream media for not being willing to answer hard questions. His chosen methods of communicating with the public have one common thread: he prefers to address the public directly, plainly, without going through the mainstream media or any reliance on further explanation by them. His social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter have completely changed the way information comes out of the prime minister’s office (PMO). Modi’s tweets, both from his personal and his prime ministerial account, keep citizens updated on his various trips (“PM will travel to Jharkhand tomorrow. Here are the details of his visit”). He also updates on his musings (“I am deeply saddened to know about Yogacharya BKS Iyengar’s demise & offer my condolences to his followers all over the world”) and highlights from speeches made across the country (“when the road network increases the avenues of development increase too”), as well as photographs and videos. Citizens are getting a front row seat at his speeches and thoughts. But not everybody is happy about this — especially not the private mainstream media.

Unlike the previous government, Modi is yet to appoint a press advisor. That person, normally chosen from senior journalists in New Delhi, advises the prime minister on media policy. There isn’t a point person from the PMO for the mainstream media — or the MSM, as it is called — to discuss stories and scoops. He only takes journalists from the public broadcasting arms — radio and TV — on his foreign trips, in contrast to his predecessor, who brought along more than 30 journalists from the public and private channels. In fact, Modi has reportedly instructed his MPs to refrain from speaking to journalists. Indian mainstream media is filled with complaints that Modi is denying journalists the opportunity to engage with complex subjects like governance beyond official statements and limited briefings. Meanwhile, some other publications have scoffed that the mainstream media is only complaining because it will be forced to analyse the news and work towards coherent reporting instead of relying of well honed cosy relationships with people in power.

This apparent rift between the PMO and the private mainstream media has to be viewed through a variety of prisms for it to make any sense. The first is the very volatile relationship between Modi and the MSM which harks back to his time as chief minister of Gujarat, when a brutal communal riot took place. The second is the state of the mainstream media itself, continuously called out for unethical practices by the likes of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

The relationship between Modi and the mainstream media is complex. No court has indicted Modi for any criminal culpability in the Gujarat riots of 2002, but many in the media have held him morally responsibly for the mass killings that carried on over three days, and let their feelings colour reports on him. But right before Modi’s historic sweep of the Indian general elections, this section of the press seemed to have begrudgingly warmed to the man they had long vilified.

One of India’s most respected journals, Economic and Political Weekly, published the article Mainstreaming Modi, deconstructing this new wave of coverage. It argued that the reasons for this change “range from how even the United Kingdom and the European Union have ‘normalised’ relations with him [Modi], that he has been elected thrice in a row to the chief ministership of Gujarat, which surely speaks of his abilities as an ‘efficient’ and ‘able’ administrator, that Gujarat has become corporate India’s favourite investment destination, and most importantly, that he is the guy who can take ‘decisions’ and not keep the nation waiting for action.”

During this year’s election campaign, Modi’s use of the media was innovative. Stump speeches were tailor made for the towns he was campaigning in. Modi’s 3D holograms, deployed in small towns while gave a speech elsewhere, were a spectacle not seen before in India. Though Modi had been speaking to Hindi and other Indian language media, he delayed giving interviews to the English language “elite” media, watched by a small but influential section of the population. He finally consented to doing a one-on-one interview with Arnab Goswami of Times Now, known as one of India’s loudest and most aggressive anchors. People readied themselves for the ultimate combative hour on television, but Modi’s no-nonsense answers, it seemed, won over both the anchor and the audience — especially as they were in sharp contrast to the vague statements put across by Modi’s challenger, Indian National Congress Party candidate Rahul Gandhi.

After the election win, India’s mainstream media has been forced to reassess what it wants from the prime minister. Is it information or is it access? The mainstream media undoubtedly has had a very complicated and close history with the political class. A Congress-led government has been ruling New Delhi for a decade, building up close relationships with senior editors and journalists. Some of these relationships were exposed through leaked conversations between members of the press and corporate lobbyists in a scandal now known as the Radia Tapes. They revealed, among other things, how journalists used their connections to politicians to pass on messages from lobbyists.

In fact, the indictment of improper behaviour by the media is a fairly regular occurrence in India. Just this month, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India released their latest report, which recommends that corporate and political influence over the media can be limited by restricting their direct ownership in the sector. For this reason, the credibility and true affiliation of the media is always under the scanner.

But Modi and his team also need to respond to questions about why they will not deal with some parts of the media. How do they view the role of a combative media? Is only the public broadcaster, which reports the story as the government wants, to be allowed access? Are critical questions being avoided?

Perhaps, the last word can go to Scroll.in, one of India’s newest online magazines: “[T]he rat race for the ego scoop undermines the most important scoop, the thought scoop. We often don’t look at the big picture, don’t take the long view, don’t see the obvious, forget the past, don’t study the boring reports, substitute access journalism for ground reporting, believe the official word. Narendra Modi might just be doing us a favour by keeping us away.”

This article was posted on August 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Aug 14 | Events

YOU CAN NOW WATCH THIS CONVERSATION AND READ A FULL ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT HERE.

Index on Censorship is delighted to announce the second in a series of online conversations about artistic freedom of expression in Wales.

This conversation forms part of our ArtFreedomWales programme looking at how artistic freedom is regarded, debated and promoted across the arts sector in Wales – in the press, by the public, by funders and policy makers.

Artists working in Welsh – opportunities and obstacles to expression?

Online conversation with:

- Mari Emlyn – Chief Executive Officer Galeri

- Arwel Gruffydd – Artistic Director Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru

- Bethan Jones Parry – Broadcaster, Journalist and Writer

- Bethan Marlow – Playwright and Storyteller

- Iwan Williams – Independent Creative Producer and Development Officer for Creadigol Mentrau Iaith Cymru

Where: Catch up with the Google Hangout here

Please note: this conversation will be in Welsh with an English summary at the end.

This is the second of four events on artistic freedom of expression in Wales that we are live-streaming, leading up to a national symposium at Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff (27th November). You will be able to email and tweet questions to the panels during the discussion.

What are the issues in Wales? What are the opportunities? What are the obstacles? What has the right to freedom of expression got to do with Wales’ major cultural debates and policies: bi-lingualism, engaging young people and ethnically diverse voices, tackling poverty, maximising on new cultural infrastructure, having an international voice?

We want to hear from everyone producing and participating in the arts in Wales who has something to say about freedom of expression.

The first online conversation which took place in July featured Tim Price (playwright), Kathryn Gray (poet and writer), Lisa Jen (musician/actor/writer) and Leah Crossley (artist). See it here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pNv1J0_jRQY

Arts Council of Wales supports this programme

22 Aug 14 | About Index, Events, United Kingdom

Mae Index on Censorship yn falch o gyhoeddi yr ail ddigwyddiad mewn cyfres o drafodaethau ar-lein am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru.

Mae Index on Censorship yn falch o gyhoeddi yr ail ddigwyddiad mewn cyfres o drafodaethau ar-lein am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru.

Mae’r trafodaethau yn ran o raglen sydd yn edrych ar sut y mae rhyddid artistig yn cael ei ystyried, ei gefnogi, ei drafod a’i hyrwyddo ar draws y sector gelfyddydol, yn y cyfryngau, gan y cyhoedd, gan ariannwyr ac gan wnaethurwyr polisi yn y DU.

Artistiaid yn gweithio yn y Gymraeg – cyfleon a rhwysterau i fynegiant.

Trafodaeth ar-lein gyda:

- Mari Emlyn – Cyfarwyddwraig Artistig Galeri.

- Arwel Gruffydd – Cyfarwyddwr Artistig Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru.

- Bethan JonesParry – Darlledwraig, Newyddiadurwraig ac Ysgrifennwraig.

- Bethan Marlow – Dramodwraig a Storïwraig.

- Iwan Williams – Cynhyrchydd Creadigol Annibynol a Swyddog Datblygu Creadigol Mentrau Iaith Cymru.

Pan: Awst 26ain 11.30yb

Ble: Google Hangout yma

Sylwer bydd y drafodaeth yn Gymraeg gyda chrynodeb Saesneg ar y diwedd.

Dyma’r ail o bedwar digwyddiad rydym yn eu ffrydio’n fyw yn ystod yr hafa fydd yn arwain at symposiwm am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru yng Nghanolfan Celfyddydau Chapter, Caerdydd (27 Tachwedd). Bydd modd i chi anfon cwestiynnau drwy system holi ac ateb Google Hangout neu drydar y panelwyr yn ystod y drafodaeth.

Beth yw’r materion yng Nghymru? Beth yw’r cyfleon? Beth yw’r rhwystrau? Beth sydd gan ryddid mynegiant artistig i wneud gyda phrif drafodaethau celfyddydol a pholisiau – dwyieithrwydd, denu pobl ifanc a lleisiau ethnig amrywiol, ymdopi â thlodi, manteisio ar rwydweithiau diwylliannol newydd, meddu ar lais rhyngwladol?

Hoffem glywed gan bawb sydd yn cynhyrchu ac yn ymwneud â’r celfyddydau yng Nghymru ac sydd â rhywbeth i’w rannu am ryddid mynegiant. Bydd y trafodaethau hyn yn bwydo agenda y symposiwm yng Nghaerdydd a bydd pob un yn rhoi ffocws ar thema gwahanol y byddwn wedi ei ganfod yn ein hymchwil cychwynnol.

Cafodd y drafodaeth ar-lein gyntaf ei gynal ym mis Gorffennaf. Yn cymeryd rhan roedd y dramodydd Tim Price, y gantores, actores a’r ddramodwraig Lisa Jên, y bardd a’r ysgrifennwraig Kathryn Gray a’r artist gweledol Leah Crossley. Mae modd ei wylio yma https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pNv1J0_jRQY

Arts Council of Wales supports this programme

22 Aug 14 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

Street art from Mohamed Mahmoud Street, Cairo. (Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

Before the January 2011 uprising, street art was little known in Egypt. Then came the revolution and with it, an outburst of creativity.

With the fall of the authoritarian regime of Hosni Mubarak, Egyptian artists who had routinely faced censorship restrictions under his autocratic rule, felt a strong urge to break out of the confines of their studios and reclaim public spaces. Young artists in particular, decided they needed bigger canvases for the grand ideas they wanted to convey through their paintings. To celebrate their newfound liberation, many of them took their art directly to the people and onto the streets, expressing their views and opinions on public walls and on the sides of buildings.

Bonded by their shared aspirations for a better Egypt, the young graffiti artists spent long hours working together, creating vivid group murals that told the stories of the revolution in which they had actively participated. The images they produced in the months following the 2011 uprising documented the dramatic changes that were unfolding in the country, the continued unrest ensuring a steady supply of material for them to work with. The artists also spread powerful messages of “equality” and “freedom” that helped shape public opinion, attitudes and values.

“Our murals added colour to the otherwise dull streets and boosted the morale of the people. But as graffiti artists and activists, we also played the role of the ‘alternative critical media,’ telling the untold stories and spreading messages that helped the public better understand what was really happening on the ground,” said graffiti artist Salma Sami, a graduate of fine arts who has also worked as a broadcaster.

An image of Pinnochio on TV, spray-painted on a wall on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, shortly after the fall of Mubarak, was intended to poke fun at state media — for long, a propaganda tool of the ousted Mubarak regime. According to Sami, the mural also “serves as a warning to Egyptians not to believe everything the media tells them”.

Besides being a critical voice, raising awareness and informing the public of the events unfolding in the country, Cairo’s nascent street art movement also helped keep the spirit of the January 25 revolution alive.

“As a woman, I wasn’t accustomed to working in the street and was afraid at first especially after hearing stories of sexual assault incidents in the very neighbourhood where we worked. But once I started working, I felt safe. Working in a group helped us revive the spirit of the revolution, letting go of our fears and uniting behind a common goal,” Sami said.

The street artists successfully managed to break down social barriers of class, religion and gender. They created a close-knit community among themselves but were also accessible to the public.

“Crowds would often gather to watch as we worked and then, someone would volunteer to help. Soon, we would find others joining in. The fact that a lot of our work was painted with roller brushes made it easy for anyone to participate,” Sami told Index.

(Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

Like Sami, Bahia Shehab — an art historian and graphic designer — was also very much a part of the street art movement that emerged and developed after the 2011 revolution. Her trademark “no” stencils, spray painted on the walls of Mohamed Mahmoud Street have helped draw public attention to social problems, exhorting Egyptians to take a stand against violence, oppression, and other forms of injustice.

Shehab joined the street art movement nine months after the revolution when she saw an image of a protester’s corpse dumped in a pile of rubbish in her Facebook newsfeed. The gruesome picture, which had gone viral on social media networks, so infuriated her that she rushed to Tahrir Square to express her rage. Her stencilled message “no to military rule” marked the beginning of her “thousand times no” campaign — a series of images decrying torture, sexual violence and other issues she felt strongly about.

Carrying on the idea from her 2010 book — a compilation of “one thousand no-s” in a multitude of Arabic calligraphy styles — she added a range of fiery messages denouncing rights abuses that were committed during the country’s transitional period. ”No to violence and thuggery”, “no to stripping girls” and “no to sectarian divisions” are just a few in her long list of stencilled images.

More than three years after the uprising that toppled autocrat Hosni Mubarak, Shehab says her “old” list is “still relevant” and her concerns “still valid”. She continues to consistently add more “no” messages, saying she is “deeply disappointed” with the turn of events in her country. Among the new additions is a stencil calling for an end to the brutal security crackdown on dissent.

A nationalist fervour sweeping the country has however made it dangerous for graffiti artists to express themselves freely. Those who dare criticise government policies are often accused of being “traitors” and “terrorists” by self-proclaimed “patriots”. Today, while many of the young street artists view former army chief and current president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as merely the new face of the old military regime, few dare depict him in their artworks. Sisi came to power following the 2013 coup that overthrew Egypt’s first democratically elected president, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi. Several established street artists have chosen to remain anonymous, signing their artworks using nicknames for the sake of their security.

“Working in the street has always been dangerous,” noted Shehab, adding that “the only difference is that the danger now comes from violent ‘patriotic’ mobs supporting the military where before it was from the police.”

But mob violence is not the only danger threatening Egypt’s street art movement. A proposed draft law banning so-called “abusive graffiti art” — if passed — may likely restrict artistic expression and may spell the end of the graffiti tradition, even before it fully emerges. Under the draft law, violators could face a prison sentence of up to four years or a fine of up to 100,000 Egyptian pounds.

The recent alleged murder of one of Shehab’s comrades — 19 year-old graffiti artist and member of the April 6 youth movement Hisham Rizk — has compounded her fears, sending shivers down many spines in Egypt’s artistic circles. Rizk’s body was found in a Cairo morgue last month, a week after his family reported his “mysterious disappearance”. A forensic report concluded that the young artist had died of “asphyxiation by drowning in the Nile River”. Sceptical fellow artists however, believe Rizk’s critical views of the government expressed in his drawings and on Facebook may have instigated a confrontation with security officials that led to his death.

(Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

“People don’t always agree with our views and different people interpret our artworks in different ways but at least our murals provide food for thought,” noted Sami who, in early 2012, designed a controversial mural depicting a skull with a military cap, holding a flower between clenched teeth. The image was a fitting portrayal of the brutal military regime that replaced Mubarak after the revolution. The 18-month rule of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) was marred by political turmoil and violence including forced virginity tests performed by the military on female protesters

You can still see Sami’s mural on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, along with many others that are critical of both SCAF and the Muslim Brotherhood. The latter are depicted as sheep, while military men are portrayed as butchers in some of the murals. The colourful artworks are reminiscent of a happier time of free artistic expression and hope — a phase that, some of the artists fear, may well be over.

Yet, both Sami and Shehab remain defiant, saying that neither laws nor intimidation will deter them from the journey they have started. They draw similarities between their art and the 2011 revolution, saying both are constantly shifting and come in waves. Their murals in downtown Cairo have been whitewashed several times with other artists painting over them or adding new images as new events unfold, sparking new ideas. “Sometimes, residents in the area paint over the images if they oppose our views,” said Sami.

“I no longer mind when my work disappears. When that happens, I just tell myself it’s time to design a new stencil and I head straight back to Mohamed Mahmoud Street.”

The Index on Censorship interactive documentary Shout Art Loud explores how Egyptians use graffiti and other art forms to tackle the issue of sexual harassment and violence against women. Watch it here.

This article was posted on August 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Aug 14 | Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, News and features, Uncategorized

Tributes to James Foley were placed at the War Correspondents Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery (Photo: Cynthia Rucker/Demotix)

On Thursday, after a video emerged of U.S. photojournalist James Foley being beheaded by Islamic State (ISIS) militants, the Metropolitan Police in London suggested that anyone who watched the video could be committing a crime. This takes us well beyond the realms of the #ISISmediablackout being urged by social media users, many of them journalists themselves, and does go to the heart of why censorship of such material is deeply problematic.

Questions of free speech and free expression are rarely clear-cut: the human rights laid out in the Universal Declaration frequently grate up against one another. Balancing the right to a privacy, for example, with the right to free expression and the public‚s right to know can be a high wire act; as is the balance between protecting children online from exposure to graphically violent or sexual content, and full-scale censorship.

And so deciding whether sharing, or even watching, a video of a criminal act, created as a deliberate piece of propaganda, rightly raises important questions. Are those disseminating this information playing into the hands of propagandists, so furthering their cause? Or are they raising awareness of their practices to a wider audience, leading to a better informed public? It is understandable that Twitter should want to respect the wishes of James Foley’s family by encouraging people not to share it. It is also understandable that Twitter and others would not want to be seen to be promoting propaganda that potentially glorifies terrorism and acts of horrific violence. It is also understandable that many social media users want to encourage an ISIS blackout, arguing that by sharing the Foley video, sharers simply give the group the oxygen of publicity and encourage more such acts.

But there is a difference between individuals exercising their right not to view or share the video, and companies such as Twitter — or indeed the police force — denying people the right to view it. If the Met police is right that just by watching the video individuals are committing a crime (and they have yet to show how or why this is), then David Cameron has broken the law. Barack Obama has also seen the video. As have I. As have a number of the journalists writing about the video in today’s papers: something they needed to do to be able to describe its full horror to others. We should not feed the flames of the propagandists by mindlessly sharing their videos, but nor should we make the mistake of assuming that global corporations, or indeed police forces, should decide who sees what. Because that simply plays into the hands of all those who want to end societies in which dissent and difference is tolerated; the kind of societies that celebrate and cherish the work of men like James Foley.

This article was posted on August 21, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Aug 14 | Americas, News and features, United States

A number of journalists have been arrested while covering the protests in Ferguson, Missouri (Photo: Abe Van Dyke/Demotix)

As news spread of a video showing the murder of American journalist James Foley by the Islamic State (ISIS), journalists and Middle East watchers were unanimous on social media: do not watch the film. And for God’s sake do not post links to the film anywhere. Do not give the killers what they want.

The descriptions were brutal enough. They echoed back over a decade, to the murder of Daniel Pearl by Al Qaeda linked terrorists in Pakistan 2001.

There is a very specific message in the public execution of journalists. It’s a hallmark of extremism, in that it signifies that your movement is far beyond attempting to use the press to “get the message out”, to garner support. This is not about rational grievances the international community could address. This is not about convincing anyone who isn’t already open to your ideas. It’s about rejecting traditional ideas under which the press operates.

But this is partly possible because the likes of ISIS no longer need the attention of press to reach the world. Much has been made of the group’s social media presence. It’s genuinely impressive, and, importantly, clearly the work of people who have grown up with the web; people who are used to videos, Instagram, sharable content. They are, to use that dreaded phrase, “digital natives”. They understand the symbolic power of murdering a journalist, but they see themselves as the ones in charge of controlling the message.

Media workers are increasingly targeted, while the previous privileges they enjoyed fade away.

As I sat down to write this column, the number of journalists arrested while covering disturbances in Ferguson, Missouri stands at 17. According to the Freedom of the Press Foundation, this number includes reporters working for German and UK outfits, as well as domestic American media.

Journalists have apparently been threatened with mace. An Al Jazeera crew had guns pointed at them and their equipment dismantled. A correspondent for Vice had his press badge ripped off him by a policeman who told him it was meaningless (in slightly coarser language).

The Ferguson story is a catalogue of things gone wrong: racism, disenfranchisement, the proliferation of firearms, a militarised police force (a concept that goes far beyond mere weaponry; this is law enforcement as occupying force rather than as part of a balanced democracy). To single out the treatment of media workers may seem a little self serving, but there is good reason to do so.

We are used to telling ourselves by now that journalism is a manifestation of a human right — that of free expression. Smartphones, cheap recording equipment, and free access to social media and blogging platforms have revolutionised journalism; the means of production have fallen into the hands of the many.

This is a good thing. The more information we have on events, surely the better. But one question does arise: if we are all journalists now, what happens to the privileges journalists used to claim?

Official press identification in the UK states that the holder is recognised by police as a “bona fide newsgatherer”. As statements of status go, it seems a paltry thing. But it does imply that some exception must be made for the bearer. The recognised journalist, it is suggested, should be free to roam a scene unmolested. One can ask questions and reasonably expect an answer. One can wield a video or audio device and not have it confiscated. One can talk to whoever one wants, without fear of recrimination.

That, at least, is the theory. But in Britain, the US and elsewhere, the practice has been changing. Whether during periods of unrest or after, police have shown a disregard for the integrity of journalists’ work. The actions of police in Ferguson have merely been part of a pattern.

The question is whether we can maintain the idea of journalistic privilege when everyone is a potential journalist.

During the legal tussles over the case of David Miranda, the partner of former Guardian writer Glenn Greenwald, an attempt was made to identify persons engaged in journalistic activity, without necessarily being employed as journalists.

Miranda was detained and searched at Heathrow airport as he was believed to have been carrying files related to Edward Snowden’s NSA leaks, with a view to publication in the Guardian, though he is not actually a journalist himself.

The suggestion made by Miranda’s supporters (Index on Censorship included) is that the activity of journalism is what is recognised, rather than the journalist.

This may be applicable in circumstances such as a border search, but how would it apply in the heat of the moment in somewhere like Ferguson, or during the London riots, or any of the recent upheavals where citizen footage has proliferated. If someone starts recording a confrontation with the authorities, are they immediately engaged in journalistic activity? Or does journalism depend on what happens to your video, your pictures, your tweets?

When everyone is a journalist, is anyone?

This article was posted on August 21, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Aug 14 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Turkey Statements

IGF 2013 was in Indonesia. This time Turkey plays host.

This year’s Internet Governance Forum (IGF) — a high-profile, United Nations-mandated annual conference on issues surrounding governance of the internet — is taking place in Istanbul, Turkey. But Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, two renowned Turkish internet rights advocates, are boycotting it. Here they explain why.

Between May 2007 and July 2014 Turkey blocked access to approximately 48,000 websites subject to its controversial Internet Law No 5651. Although the law is ostensibly aimed to protect children from harmful content, from the very beginning it has been used to prevent adults’ access to information. In February amendments made to the legislation extended blocking provisions to include URL-based blocking of internet content. The same amendments compelled all internet service providers (ISPs) to be part of an association for access providers to centrally enforce blocking orders within four hours of receipt. It also introduced one-to-two-year data retention requirements for hosting companies and all ISPs. Furthermore, subject to new provisions, ISPs are required to take all necessary measures to block alternative access means such as proxy websites and other circumvention services including, possibly, VPN services. The amended version of the law also shields staff from the Presidency of Telecommunications and Communication (TIB) from prosecution if they commit crimes in their work for the telecoms authority.

In March access to both Twitter and YouTube was blocked arbitrarily and unlawfully by the TIB. With both blocking orders the government aimed to prevent the circulation of graft allegations ahead of local elections to be held on 30 March. During the blocking period, the authorities also ordered major ISPs to hijack Google and OpenDNS’s DNS servers, tampering with the DNS system to surveil communications, as well as to prevent users from circumventing blocking orders. Turkey’s constitutional court stated that the blocking of Twitter by TIB constituted a grave intervention on the freedom of expression of all Twitter users. Furthermore, in a 14-2 majority judgment, the court decided that the YouTube ban infringed on freedom of expression protected by the constitution.

However, despite these strong rulings, Twitter decided to implement its country withheld content policy for Turkey and started to block access to certain Turkish accounts and individual tweets. It was reported in June that Twitter complied with 44 out of 51 court decisions since they visited Ankara on 14 April, and the US-based social media platform continues to aid and assist Turkish authorities in censoring political content.

Facebook has also banned the pages of a number of alternative news sources, including Yüksekova Haber (Yuksekova News), Ötekilerin Postası (The Others’ Post), Yeni Özgür Politika (New Free Policy), Kürdi Müzik (Kurdish Music), and other groups related to Kurdish movements. The site has also been criticised for removing several pages related to the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP). Regardless of the above-mentioned constitutional court decisions, access to popular platforms such as Scribd, Last.fm, Metacafe, and Soundcloud is currently blocked from Turkey. Access to WordPress, DailyMotion, Vimeo and Google+ has in the past year been blocked temporarily by court or administrative orders. A number of alternative news websites that report on Kurdish issues, including Firat News, Azadiya Welat, Dengemed and Keditor, remain indefinitely blocked. In total it is estimated that 200 websites are banned indefinitely for their pro-Kurdish or left wing content.

Over the past year, many people have received suspended sentences and fines for their social media activity, usually on charges related to terrorism, blasphemy, or criticism of the state and its officials. In the crackdown following the Gezi Park protests of June 2013, dozens of people were detained over their social media posts. Criminal investigations and prosecutions were initiated subject to Articles 214 and 217 of the Turkish criminal code concerning incitement to commit a crime and disobey the law, as well as miscellaneous provisions of Law No 2911, on demonstrations and public meetings. In September 2013, pianist and composer Fazil Say was given a suspended sentence of 10 months and court supervision for insulting religious values in a series of tweets. Such criminal investigations and prosecutions have a chilling effect on all social media platform users.

In addition to widespread blocking of websites and content as well as criminal investigations and prosecutions to silence political speech, the Turkish authorities are also building surveillance infrastructure, which includes the deployment of deep packet inspection systems to monitor all forms of communications unlawfully.

Therefore, we have decided to boycott IGF 2014 hosted by Ministry of Transport, Maritime and Communications and coordinated by the Information and Technologies Authority. We also confirm that we will not be taking part in the IGF.

Yaman Akdeniz & Kerem Altiparmak

This edited version of the statement has been republished with permission from the authors. You can find the original and fully referenced statement here.

20 Aug 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Letters, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

Rasul Jafarov in September 2013 (Photo: Melody Patry)

In early August, Azerbaijani human rights activist Rasul Jafarov was charged with tax evasion, illegal entrepreneurship and power abuse and sentenced to three months of pre-trial detention, as part of a crackdown on the country’s human rights groups and dissident voices. This is his appeal to the international community.

Ladies and gentlemen, dear friends,

I would like to bring to your attention that the charges brought against me are completely unlawful and groundless. One might ask why? Because,

- I was registered as an individual entrepreneur with the tax authorities on 25 August 2008 and obtained a taxpayer identification number (TIN). From that time up until now, I fully and timely paid relevant taxes and social insurance contributions in accordance with the funds paid to me for my services under the projects in which I was involved. It can be easily verified by sending an inquiry to tax agencies.

- The Human Rights Club was founded in December 2010, and at the founding meeting I was elected the chairman of the organisation. The Human Rights Club has repeatedly applied to the ministry of justice for registration, but due to unjustified and unlawful denial of state registration, appeals were made to all relevant courts in Azerbaijan, and at present this case is pending before the European Court [of Human Rights]. The process of seeking registration and filing appeals continued from 2011 till 2013; since the legislation during this period did not prohibit the activity of unregistered NGOs, we, as the Human Rights Club, implemented a variety of projects during the years 2011-2013. Each of these projects was carried out under the grant agreements signed with donor organisations which I have voluntarily presented to the prosecutor general’s office. Also, at the time of signing of these agreements, the ministry of justice was informed through relevant letters sent to this state body. Moreover, the funds under each grant were transferred not in a secret or non-transparent manner, but through transfers to the bank accounts open and accessible for law enforcement and other relevant agencies, with the purpose of each transfer being indicated as “grant”. Since the Human Rights Club (HRC) was not registered, as the chairman of the HRC the transfers were made to my bank accounts. In this case, what kind of illegal entrepreneurship or abuse of office or tax evasion one can talk about?

You may wonder then why I was arrested. Let’s pay attention to the projects examined by the investigators and covered by the indictment:

- Human rights campaign related to Eurovision — Sing for Democracy; Art for Democracy campaign that uses different types of art to promote and protect human rights; increasing voter turnout on the eve of elections and so on. Along with being in the spotlight of the local and international community, all of these projects were targeted in libellous and insulting articles of the pro-government media which also included the ruling party’s official newspaper Yeni Azerbaijan.

- Azerbaijani government argues everywhere and at the highest level that there are no political prisoners in Azerbaijan. However I and my colleagues do not argue, but prove that there are political prisoners in Azerbaijan.

- During the session of the parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe held in June 2014, i.e. shortly before my arrest, a roundtable was held on the gravity of the human rights situation in Azerbaijan. I was the person who was directly involved in determination of everything from the technical aspects to the content of the roundtable (together with Intigam Aliyev, Emin Huseynov and Rashid Hajili who are currently persecuted). I was also involved in organising the flash-mob held by our young friends on the day of Ilham Aliyev’s speech. And finally, in the past 2-3 years everyone was asking half-joking, half-serious, when I was going to be arrested. It happened, and now I’m looking forward to your support! Thank you everyone

Sincerely,

Rasul Jafarov

Baku Pre-Trial Detention Center (Kurdakhani settlement)

14 August 2014

19 Aug 14 | Malaysia, News and features, Religion and Culture

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

It is said that the Muslim jurist al-Shafi’i so revered the name Allah that he wore a ring inscribed with a message to himself from God. One might think, then, that the name would be universally celebrated in those countries where the doctrine of al-Shafi’i is the predominant school of Islamic jurisprudence. But this is not the case in Malaysia. In June, the federal court turned down an appeal by a Catholic bishop against a decision of the ministry of home affairs to impose limits on certain uses of the word Allah.

The story dates back to 2009, and a letter from Che Din bin Yusoh, a civil servant working for the ministry, to the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Kuala Lumpur, Murphy Nicholas Xavier Pakiam. It approved a permit to publish The Herald, a weekly Catholic newspaper available in English, Chinese, Tamil and Bahasa Melayu, the official language of Malaysia. On the face of it, the letter contained good news: renewed permission to publish The Herald, in print since 1994. But it also stipulated two conditions: that Pakiam and the Bishops of Peninsular Malaysia confine their distribution of The Herald to the church and its adherents; and that they refrain from printing the word Allah in the Bahasa Melayu version.

The first condition was inconsequential as far as the bishops were concerned: The Herald had only ever been distributed amongst the congregants of the country’s three archdioceses. Furthermore, since the 1970s and 80s, the church had adopted a largely ecumenical posture towards the other religious establishments in Muslim-majority Malaysia, partly in response to the rise of the Islamic dakwah, or missionary, movement. (Proselytising Muslims is also an offence under Malaysian Federal law.)

The second condition, however, was intolerable to the bishops. Allah, from Arabic, is the Bahasa word for God irrespective of the religious context in which it is used — just as it is for Bahasa-speaking Sikhs, Indonesian and Arabic-speaking Christians, Mizrahi Jews, Maltese Catholics, and many other non-Muslim groups — and it appears in Al-Kitab, the Bahasa translation of the Bible. The second condition effectively forbade the use of the word Allah in the Bahasa version of The Herald in reference to any God but the Islamic deity.

And so Pakiam went to court, seeking judicial review of the government’s decision to impose the second condition. He asked for an order of certiorari, quashing the decision. He also asked for a series of judicial declarations: that imposing such a condition violated certain fundamental freedoms enshrined in the constitution — the rights to freedom of speech and to practice non-Islamic religions in peace and harmony — and, in a bold move that invited the Malaysian judiciary to pronounce dispositively on a matter of considerable religious sensitivity, that the word Allah is not exclusive to the Islamic faith. The bishops also asked the Court to find that the decision was irrational and unreasonable, contravened the laws of natural justice, and had been made in bad faith.

The ministry’s decision to impose the Allah condition can only be understood in the light of a series of laws passed by ten of Malaysia’s thirteen state legislatures. These enactments — each called some variation on the Control and Restriction of the Propagation of Non-Islamic Religions — proscribe the use of any of 25 words or 10 phrases in reference to a religion other than Islam. (The Johor state enactment doesn’t include a list of words or phrases but imposes a blanket ban on the use of words of “Islamic origin”.) The list of words could double as a glossary of key terms for any student of Islamic theology: Allah, Fatwa, Hadith, etc.; and the list of phrases contains such Islamic maxims as Alhamdulilah and Allahu Akbar. The laws vary in their severity — what might in Terengganu lead to a fine of 1000 ringgits could in Kelantan result in a five-year jail term and/or whipping — but so sacrosanct are they in the eyes of many that five states, as well as the prefecture of Kuala Lumpur and the Chinese Muslim Association of Malaysia, attempted (unsuccessfully) to join the government as defendants in Pakiam’s action.

But on the final day of 2009, the high court found in favour of Pakiam and the Bishops of Peninsular Malaysia, marking either a victory for freedom of speech or a lamentable triumph of secular values over democratic choice in a majority Muslim country, depending on one’s view. The issue, however, was far from resolved. For one thing, the government appealed against the decision of the high court, as did the five states. For another, the high court had not been asked to review the legality of the various non-Islamic religions enactments — merely the decision to impose the condition contained in bin Yusoh’s letter — and so, they remained good law.

This would prove troublesome for Malaysia’s Christians. In early 2011, it was reported that the Islamic affairs departments of certain states had raided the premises of various Christian organisations, including a Bible-import business called Gideon, and impounded tens of thousands of Bahasa and Iban-language Bibles, citing the Non-Islamic religions enactments as justification. This prompted the prime minister of Malaysia, Mohammad Najib Abdul Razak, to write to the chairman of the Christian Federation of the country, proposing a ten-point solution to defuse the welling inter-religious tension. The letter affirmed that Bibles in any language could be imported into the country, but stipulated that Bahasa-language Bibles, whether imported or locally-produced, must have a crucifix and the words Christian publication printed on their front.

The inclusion of this proviso made clear the strength of the government’s fear of non-Islamic and secular proselytising encouraged by the ready availability of Bahasa-language Bibles — fear of the “naked public square”, increasingly devoid of Islamic speech and thus increasingly hostile towards Islam in general, to paraphrase the American Catholic writer John Neuhaus. Given this anxiety on the part of the Government one might think that all the parties would have embraced the ten-point proposal as a much-needed compromise. But for various reasons — the peculiarities of Malaysian domestic politics and the procedural limitations of the justice system, to name two — the proposal was never enshrined in law and the various state enactments remained untouched. Preserving the status quo, however, meant that incidents of Bible-seizing continued; the most recent widely reported case occurred earlier this year, in Selangor province.

And then, as if to rub salt in the Bible-seizing wound, the court of appeal ruled unanimously in favour of the ministry and set aside the decision of the high court. The bishops were given leave to appeal but, on 23 June of this year, the Federal Court of Malaysia turned down their application and upheld the decision of the court of appeal, thus drawing the case to an unsatisfactory close.

The decision of the federal court — decided by a narrow four-to-three margin — is disappointing not only in the result but in the reasons given, too. Like many administrative law cases, the judgment is preoccupied with questions of procedural, rather than substantive, unfairness. This would be tolerable if the decision taken by the ministry had not impacted on fundamental rights enshrined in the federal constitution: Article 3 asserts that while Islam is the official religion of the federation, this should not impinge on the rights of non-Muslims to practice other religions in peace and harmony.

But, in banning the use of the world Allah in a weekly newspaper, the decision clearly affected the rights of individuals to freedom of speech and religion. The questions put before the court were held by the three dissenting judges to be of such constitutional importance that all three chose to write opinions setting out their reasons, an incredibly rare occurrence in judicial review proceedings of this kind: “too weighty to suffer indifference,” wrote Justice Zainun Ali.

The majority opinion of Justice Arifin Zakaria, by comparison, is preoccupied by the far more incidental question of whether the appropriate standard in evaluating the reasonableness of a decision taken by the ministry should be objective or subjective. And Justice Zakaria also concludes that the decision of the Court of Appeal must be correct because Pakiam had not sought to challenge the various state enactments before the high court. As the enactments were not the object of judicial review, Zakaria can only conclude that the decision to impose a condition on the propagation of non-Islamic religion was in keeping with the letter and spirit of those laws and not, therefore, an abuse of power. If put forward in a contextual void this argument might be persuasive. However, Zakaria also upholds the decision of the court of appeal on the basis that Pakiam would have erred if he had sought to challenge the various state laws before the high court, as the only appropriate forum in which to bring such a challenge would have been the federal court. Pakiam and the bishops were predestined to lose, it would seem.

If there were a southeast Asian regional court of human rights, we might think that the Bishops of Peninsular Malaysia would have good grounds to get on its cause list. Presuming the existence of some regional charter of fundamental rights, similar in content, say, to the European and American Conventions on Human Rights, the bishops would surely be able to rely either on a breach of the fundamental rights or on the denial of an effective remedy at law. And given the relative willingness of supra-national courts to scrutinise governmental arguments premised on public order and/or national security with greater force, we might even imagine such a regional court to declare the various non-Islamic religions enactments in breach of such a charter.

Then again, such a court might equally take into consideration the fact of Malaysia’s Muslim-majority population and conclude that the government had acted to protect the religious rights of the majority from the tyranny of a minority. In the now-famous European case of Lautsi v. Italy, the European Court of Human Rights held that the display of crucifixes in Italian state schools was not in breach of Article 9 ECHR (the right to freedom of conscience and/or religion). But whereas in Lautsi it was held that the “negative” right to freedom of religion did not endow individuals with the right to be always and ever free from encountering religious imagery, in Malaysia the various state laws actively impinge on the exercise of a minority religion. The result of Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop of Kuala Lumpur vs. The Government of Malaysia has led many to conclude that questions of religious coexistence and the true ownership of the word Allah cannot be resolved through the courts. That is undoubtedly true. But in the meantime, if Archbishop Pakiam and the Bishops of Peninsular Malaysia feel that they have been the victims of a miscarriage of justice, then that would be true, too.

This article was posted on August 19, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

18 Aug 14 | Campaigns, Honduras, Statements

Attorney General Oscar Chinchilla Banegas

Ministerio Público, Lomas del Guijarro

Avenida República Dominicana

Edificio Lomas Plaza II

Tegucigalpa, Honduras

Email: [email protected]

13 August 2014

Dear Sir,

Dina Meza [1], journalist and human rights defender, is seeking a formal update on the investigations into threats that have been received towards her and her family.

The threats forced her to leave Honduras in 2012. Since her return in 2013, the threats have restarted and have recently been growing. She has reported being followed and receiving threating phone calls at home late at night.

As defenders of free speech, we urge you to take these threats very seriously and help ensure that Dina can continue to work without fear. Last month alone, political radio presenter Luis Alonso Fúnez Duarte and TV reporter Herlyn Espinal have both been killed.

We urge you to make Honduras a safe place for all journalists in accordance with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Please could you ensure that Dina Meza receives a formal update within 30 days.

Signed

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO Index on Censorship

Dario Ramirez, Article 19 Central America

—

Estimado Señor Fiscal General,

Dina Meza, periodista y defensora de derechos humanos, está solicitando un informe oficial sobre las investigaciones de las amenazas recibidas en su contra y la de su familia.

Las amenazas la obligaron a abandonar Honduras en 2012 y desde su regreso en 2013, estas se han reanudado y recientemente hasta han aumentado.

Meza ha denunciado haber sido seguida y haber recibido llamadas amenazas telefónicas en su casa a altas horas de la noche.

Como defensores de la libertad de expresión, le instamos a que tome estas amenazas con suma seriedad y a que ayude a garantizar que Dina pueda seguir trabajando sin miedo.

En el último mes, fueron asesinados el presentador de radio política Luis Alonso Fúnez Duarte y el reportero de televisión Herlyn Espinal.

Le solicitamos que convierta a Honduras en un lugar seguro para los periodistas, como lo indica la Declaración Universal de los Derechos Humanos. Le pedimos que le envíe a Dina Meza un informe oficial antes dentro de 30 días.

Atentamente

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO Index on Censorship

Dario Ramirez, Article 19 Central America

—

[1] Dina Meza was nominated for an Index Award for journalism in 2014.

See Amnesty’s latest report on Dina Meza’s situation

Mae Index on Censorship yn falch o gyhoeddi yr ail ddigwyddiad mewn cyfres o drafodaethau ar-lein am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru.

Mae Index on Censorship yn falch o gyhoeddi yr ail ddigwyddiad mewn cyfres o drafodaethau ar-lein am ryddid mynegiant artistig yng Nghymru.