29 Mar 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The undersigned international press freedom groups call on Turkish authorities to immediately release the 12 printworkers and staff arrested on 28 March at the premises and print works of the newspaper Özgürlükçü Demokrasi and the further 15 staff taken into custody after home raids on the morning of 29 March 2018. Authorities must also restore control over the paper and its premises to the rightful owners.

The below-named organizations also denounce the fact that lawyers acting for those arrested have been denied contact with prosecutors or access to any written documentation in relation to the raids.

Two officials purporting to be from the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (TMSF) are in place at the print works and premises of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi, a pro-Kurdish daily, and claim to be holding the sites until they receive further instructions. For its part, the TMSF, now part of the Ministry of Finance’s Directorate of National Estates and formerly an independent banking watchdog under the auspices of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, has denied having received instructions to seize the newspaper’s assets.

According to lawyers acting for the detained printworkers and Özgürlükçü Demokrasi’s principal signatory İhsan Yaşar and Kasım Zengin the owner of Gün Printing Advertising Film and Publishing Inc, where the newspaper is printed, a press crimes investigation into the paper was opened on February 7. This was followed by a separate counter-terrorism investigation that began on March 23. It is believed that both investigations, of which no written notification has been made to the paper, are in relation to Özgürlükçü Demokrasi’s coverage of Turkey’s incursion into Afrin, northern Syria.

As the sole remaining Kurdish daily newspaper in Istanbul, Özgürlükçü Demokrasi is vital in maintaining the extremely fragile access to information that is not controlled by the state. Following the closure of other pro-Kurdish newspapers and television stations such as Azadiya Welat, IMC TV and Hayatın Sesi in 2016, Özgürlükçü Demokrasi is one of the last sources of pro-Kurdish daily printed news in Turkey.

“The Turkish authorities must halt their sustained repression of Kurdish culture and language. We are highly alarmed by the onslaught on Kurdish and pro-Kurdish media outlets and journalists that has intensified dramatically since the crackdown on freedom of expression since the attempted coup of July 2016, and now reached a new low point with this takeover of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi,” said Carles Torner, Executive Director of Pen International.

We, the signatories of this statement, strongly condemn the takeover of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi, which has taken place without any legal justification or documentation. We reject the denial of information and prosecutorial access to lawyers acting for Özgürlükçü Demokrasi’s arrested staff members.

“The government’s takeover of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi is extremely concerning,” said Joy Hyvarinen, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship, “We urge European and other governments to condemn the obliteration of free media in Turkey.”

We call for the release of the arrested staff members and printworkers and official confirmation from the TMSF of the legal status of the alleged acquisition of Engin Publishing Print Inc. — and the Gün Printing Advertising Film and Publishing Inc.

Katie Morris, Head of Europe and Central Asia Programme at Article 19 said: “The takeover of Özgürlükçü Demokrasi restricts the space for freedom of expression even further in Turkey and curtails the right of the public to access information on issues of public interest, particularly in relation to the on-going conflict in the South East of the country. We call for the authorities to cease harassing this newspaper and restore much-needed media freedom in Turkey.”

The takeover of one of the last remaining opposition newspapers follows the acquisition last week of Turkey’s largest media organization and newspaper distributor, Doğan Group, by Turkish conglomerate Demirören, whose media outlets are known for taking a pro-government stance. In the week prior to the purchase, an internet streaming bill was passed granting the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) sweeping powers to monitor, license and block online streaming channels and news providers.

“This latest act against freedom press confirms that Erdogan wants to repress any free voice in Turkey. A firm position in Europe is needed to make pressure the Turkish government to restore the rule of law as soon as possible with the cessation of the state of emergency,” said Antonella Napoli member of Articolo 21 and coordinator of Free Turkey Media in Italy.

International Press Institute (IPI)’s Turkey Advocacy Coordinator Caroline Stockford said, “IPI strongly condemns yesterday’s raid and the government’s tactic of shutting down Özgürlükçü Demokrasi in an apparently illegal manner in order to silence dissenting voices in the run-up to the presidential elections. Despite the opportunity presenting itself at this week’s Varna summit, Europe failed again to strongly condemn Turkey’s repression of free media and free speech.”

The peoples of Turkey have a right to access informative opposition reporting in order to form a balanced opinion, especially in the lead up to an election. We call on Turkey to respect the human right to freedom of expression and to refrain from its practice of stifling all opposition media and to release the Özgürlükçü Demokrasi workers from detention.

We, the undersigned, call on European newspapers and governments to make clear statements to Turkey that access to balanced, critical reporting is essential to democracy and that the freedom of the press must be respected and maintained.

International Press Institute (IPI)

Pen International

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

The European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF)

Article 19

Norwegian Pen

Index on Censorship

English Pen

Articolo 21

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Pen Belgium/Flanders

Wales Pen Cymru

Pen Germany

Pen Club Français

Pen Suisse Romand[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522334755757-294591af-d9eb-2″ taxonomies=”1743″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Mar 18 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”99113″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]

Organised or state-instigated attacks against journalists, news organisations or the very idea of news itself range from intimidation to assassination: A social media campaign urging the gang rape of a female reporter; the stoning of a TV network’s service vehicles; the head of government publicly insulting editors; the engineered buy-out or outright closure of a critical news organisation; an advertising boycott; a culture of death threats and legal harassment targeting journalists; the prospect of adverse legislation or jurisprudence unduly restricting the freedom of the press; the jailing of journalists and media workers on fabricated charges; physical assault on or outright assassination of critical voices in the media. How can journalists fight back?

This panel will draw lessons from ongoing campaigns to fight back against attacks on journalism and discuss questions of theory and policy: Should journalists even file criminal libel suits, when they are advocates of freedom of expression? How far should news organizations or associations go to protect journalists at risk? When democracy itself is at stake, what political options are open to journalists?

(A workshop on the same theme, focusing on practical defences against attacks online and on social media, will take place on Friday).

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90098″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99091″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99090″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Mar 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, Press Releases, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A Scottish politician lodged a motion in the Scottish Parliament on 27 March on media freedom following Index on Censorship’s annual Mapping Media Freedom report, crediting its authors for “their continued endeavours to defend media freedom and protect journalists”.

Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project monitoring threats to media freedom in 42 European and neighbouring countries, recorded 1,089 violations in 2017. As the motion notes, a majority of these threats came from official or governmental bodies.

The motion, put forward by Andy Wightman MSP of the Scottish Greens, “deeply regrets” the loss of life of those journalists murdered throughout Europe in 2017 while conducting their duties: Maltese journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia; Swedish freelancer, Kim Wall; Syrian investigative mother and daughter team based in Turkey, Orouba and Halla Barakat; and three Russian journalists, Nikolai Andrushchenko, Yevgeny Khamaganov and Dmitri Popkov.

The motion “condemns what it sees as the day-to-day challenges facing journalists who are seeking to hold power to account”, notes some of the most worrying trends throughout the year, including the assault of 178 journalists and the 367 instances of psychological abuse of journalists, and criticises the “deliberate silencing of people and organisations by economic, political or criminal interests” through civil litigation and other legal measures.

The motion received cross-party support from Scottish Green MSPs Ross Greer, Patrick Harvie and Mark Ruskell, SNP MSPs Kenneth Gibson and Mairi Gougeon, and Labour MSP Pauline McNeill.

“We are pleased that Mr Wightman has brought the important issue of media freedom to the Scottish Parliament,” said Index on Censorship chief executive Jodie Ginsberg. “Index is deeply concerned by the growing trend of threats to the media in the region and it is important politicians do their utmost to protect this fundamental pillar of democracy.”

You can read the full report, authored by Index on Censorship’s assistant online editor Ryan McChrystal, here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522314174440-fa9adb32-fe93-2″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Mar 18 | Global Journalist, News and features, Uzbekistan

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Journalist and author Hamid Ismailov

Hamid Ismailov deserves an apology. Or at the very least, an explanation.

It has been 26 years since the events that led Uzbek journalist Hamid Ismailov to leave his home country of Uzbekistan and flee to the United Kingdom. In the 1990s, Ismailov was working with a BBC television crew to make a film about Uzbekistan. The repressive regime in power under Islam Karimov opened a criminal case against Ismailov. The authorities said Ismailov was trying to overthrow the government.

Friends advised Ismailov to flee Uzbekistan after threats against his family and attacks on his home. So he did. Twenty-four years later, he still hasn’t been back.

That’s not for lack of trying. Ismailov attempted to go back as recently as last year after the death of Karimov in 2016. He was denied entry.

One of the most widely published Uzbek writers in the world, Ismailov’s books are banned in his home country. Mentions of Ismailov are not tolerated. His existence has essentially been erased from the daily cultural life of his homeland. However, in the age of the internet, Ismailov has found ways to reach the Uzbek audience through social media sites like Facebook. He posts his novels to Facebook where Uzbeks can read them.

According to Reporters Without Borders’s press freedom index, Uzbekistan is ranked 169th out of 180 countries. With traditional media tightly controlled, the government’s attention has more recently begun cracking down on the independent news websites and instant messaging apps.

After Karimov’s death in 2016, Prime Minister Shavkat Mirziyoyev assumed power. On 2 March 2018, Uzbekistan released the world’s longest-imprisoned journalist Yusuf Ruzimuradov, who had been imprisoned for over 19 years. Ismailov expressed joy at the news of Ruzimuradov’s release but remains doubtful saying, “as much as I am hopeful, I am skeptical as well”.

In his time in exile in the United Kingdom, Ismailov has worked for the BBC World Services. In May 2010, Ismailov was appointed the BBC Writer-in-Residence, a position he held until the end of 2014. Ismailov is currently the editor for Central Asian Services at the BBC.

Hamid Ismailov spoke with Index on Censorship’s Sydney Kalich about the state of human rights in Uzbekistan, his time in exile and his newly translated book, The Devil’s Dance. Below is an edited version of their interview:

Index: What was the human rights situation like in Uzbekistan before you left and how has the situation changed over the last 23 years?

Ismailov: Unfortunately it has worsened over the years because of the autocratic regime of president Karimov, who was in power at that time and died in 2016. So all this time the situation with human rights was quite dire in Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan was always in the lower, in the bottom part of the human rights records in the world. So, nowadays with the new president, the way Shavkat Mirziyoyev acts makes us hopeful that the situation with human rights is improving because several political prisoners were freed from prison. Some activities and press have started to be more active and more open. There’s a glimmer of hope that things will improve. But at the same time — looking around at other countries with new leaders who pretended first to be reformers but then revert to the policies of previous rulers — I am also a bit skeptical. As much as I am hopeful, I am skeptical as well.

Index: You tried to go back to Uzbekistan last year and were turned away, do you think you’ll see your country again?

Ismailov: Yes, it was quite unfortunate because even under the previous authorities I attempted twice to enter Uzbekistan after the Andijan events of 2005, but the new administration did not allow me to enter the country. That was quite a shock. I think that they owe me an apology for why they didn’t allow me into my own country. I am one of the writers that is quite well known in the west and all over the world who promotes Uzbek literature, maybe most of all. So why haven’t I been allowed into the country? I need an explanation and at least an apology before I decide what to do next.

Index: And you’ve felt that way each time you’ve been refused entry, you just feel like you need an apology?

Ismailov: I think so. I didn’t commit any crimes against Uzbekistan. I didn’t do anything or any harm to Uzbekistan. All I am doing is promoting the literature and the culture of Uzbekistan all over the world. Therefore, I am a bit shocked and perplexed why I haven’t been allowed into Uzbekistan. It is where all my relatives live, I was planning on going to the grave of my mother to pay tribute. But when I planned everything, all of a sudden, I was kicked out of the airport.

Index: You haven’t lived in the country since 1992, but you still publish in Uzbek. Does this mean you still write with an Uzbek audience in mind, rather than a western audience?

Ismailov: I write in different languages. I write in Uzbek. I write in Russian. I write in English as well. So different languages for different audiences. If I write in Uzbek, it’s probably for Uzbeks, not many English people or Russians are reading in Uzbek. The translations serve me well because of the ban on my books in Uzbekistan. But in the age of the internet, the bans don’t matter too much because I can still publish my work on the net. Another thing is that people are afraid to name me or discuss me because they know the consequences of that. Nonetheless, the internet makes my life much easier.

Index: Your new book, The Devil’s Dance, is about to be released to the UK market in English, what is it about?

Ismailov: In fact The Devil’s Dance is not a new book. I finished it in 2012 and then published it in Uzbek on Facebook. It was quite viral at the time. It seems new because it’s been translated to English. In fact, I wrote three novels after that one and I just finished an English novel. The Devil’s Dance is the story of the iconic writer, Abdulla Qodiriy, the most revered 20th Century Uzbek author, who wanted to write a novel which would supersede all he had written before. We know what this novel was meant to be about but while he begun to draft this novel he was arrested. Ten months later, in 1938, he was shot dead in the Stalinien prisons. My novel is about Qodiriy’s days in prison when he thinks about his famous unwritten novel. There are two novels in one. I dared to write a novel for him. It happens in his mind so it’s not 100 per cent written but there are rough drafts, there are stories, there are intentions and ideas. It’s a written but — at the same time — an unwritten novel.

Index: How did your time as writer-in-residence at the BBC influence you as a journalist?

Ismailov: It was fun but at the same time I felt a great responsibility because I was representing this great cohort of writers like George Orwell, V. S. Naipaul and others. I was feeling like an embodiment of those people. I was trying to show what the writership means for the organisation, what the creativity means for this organisation.

Index: What do you think the most difficult part about being a journalist in exile has been?

Ismailov: The most difficult part is not being with your people on a daily basis. Though virtually you are with them on a daily basis but you don’t see them face to face, that’s the biggest part. There are bonuses to being in exile though. When you start to look at your part of the world or your country with a bird’s eye view in a way. You can see the perspective of your country within the world. You can compare the experiences of your country to other parts of the world and you can bring experiences or similar experiences of other countries into your world. So there are pluses and minuses.

Index: How do you think your reporting has changed since you’ve been in exile?

Ismailov: I think journalism in the former Soviet Union was a very conceptual one. It was about the concepts and big schemes rather than human stories. BBC Journalism is more about human stories, you approach the reality through human stories and human experiences. So that was the most striking difference and striking experience for me. As a writer, I always treat my stories through the experiences of my characters so that was a very similar in western journalism as well. So therefore, it was a harmony for me working in journalism here. As a writer, you approach through the characters, as a journalist here you do the same.

Index: You once mentioned that some people feel more connected to their home country’s culture and more pride in their culture after leaving their country, do you feel that way about Uzbekistan culture?

Ismailov: Yes, I do. Yes, I feel responsible for my culture because when I think about my forefathers, about my grannies and about my aunties, about all people whose input in my culture was so great – I have to return something to this culture which made me what I am today. But at the same time, I feel part of different cultures, of the Russian culture, of the English culture as well, now that I have been living in the London for the past 24 years. I have never lived in one place for so long. So therefore, I pay tribute to this country and I am in debt to this country. I am writing several novels in English as well to pay my tribute to this country and to this culture.

Maybe Uzbekistan even owes Ismailov a thank you.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/tOxGaGKy6fo”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook). We’ll send you our weekly newsletter, our monthly events update and periodic updates about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share, sell or transfer your personal information to anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Mar 18 | Awards, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/M6Amr_zAgpc”][vc_column_text]Team 29 is an informal human rights association of lawyers and journalists that defends those targeted by the state for exercising their right to freedom of speech.

Run by prominent human rights lawyer Ivan Pavlov, Team 29 is based in St Petersburg and named after Article 29 of the Russian Constitution on freedom of expression.

“We use court cases not only as an opportunity to restore justice within a specific case, but also as an excuse to attract public attention to the problems of freedom of information in Russia,” said Team 29.

By taking up high profile human rights cases, and writing and disseminating information about them, Team 29 has found a way around some of the restrictions imposed on campaigners.

The legal part of the Team conducts about 50 court cases annually. These are cases of high treason and the disclosure of state secrets of journalists and citizens whose right to freedom of speech is infringed, the refusal of the state to share information, and cases of extremism.

This year, the journalist section of the team set up a website to report on legal cases, explain the background to policies which threaten free speech, give advice, and explain what is happening to human rights in Russia and the different and myriad ways it is under attack.

It is the successor organisation to the Freedom of Information Foundation (FIF), which existed between 2004 and 2014, but which was shut down by the Russian government after it was included in the state register of “foreign agent” non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

The very right of civil society organisations to exist has been cast into doubt in Russia over the past few years and ever tightening restrictions placed on public protest and political dissent, making the work of Team 29 of increasingly vital importance as the space for free expression shrinks in the country. Most human rights organisations based in Russia have been closed down and it is very difficult to campaign.

Last year, Team 29 lawyers took on the Russian state to find out the fate of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust, but was captured by Soviet intelligence, placed in the Lubyanka prison and never seen again.

Last year, Team 29 lawyers took on the Russian state to find out the fate of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust, but was captured by Soviet intelligence, placed in the Lubyanka prison and never seen again.

Journalists of Team 29 have also developed their niche media about state secrecy this year. Journalists of the team conducted their own investigation into the behaviour of Sochi’s “state officials” on the back of the Sevastidi case and are conducting a special project The Seventeenth Year in which they compare 1917 and 2017 in the history of Russia. They want to have videos on their site and develop their human rights campaigning work.

“It is a great honour for the whole Team 29 to be nominated for the Freedom of Expression Awards together with colleagues from Iran, Egypt, and Kenya, who are risk their lives constantly due to their work,” said Team 29. “Several years ago, it seemed not so dangerous to be a human rights defender or activist in Russia. We just didn’t know about a lot of cases of violence towards activists before; however, today we hear more and more news about tortures by the police, people vanishing, or security services’ secret prisons. The more people who know about our work, the better protected we become and the better chance we have to achieve our objectives and to help people whose rights to information access are abused in Russia.”

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460×490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522067531601-cc030204-bc1b-9″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Mar 18 | Event Reports, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“We must distinguish the things that are intellectually dishonest and aimed at persuading, which is traditionally called propaganda, and the things where people are trying to give you general information, which doesn’t have the absolute intention of persuading you,” said The Times columnist David Aaronovitch at a panel at the Essex Book Festival.

Aaronovitch, also Index’s chair, was discussing the role of propaganda with leading expert on the darknet and technology Jamie Bartlett and Chinese-British author Xinran, who was the first woman to have a late-night radio show in China.

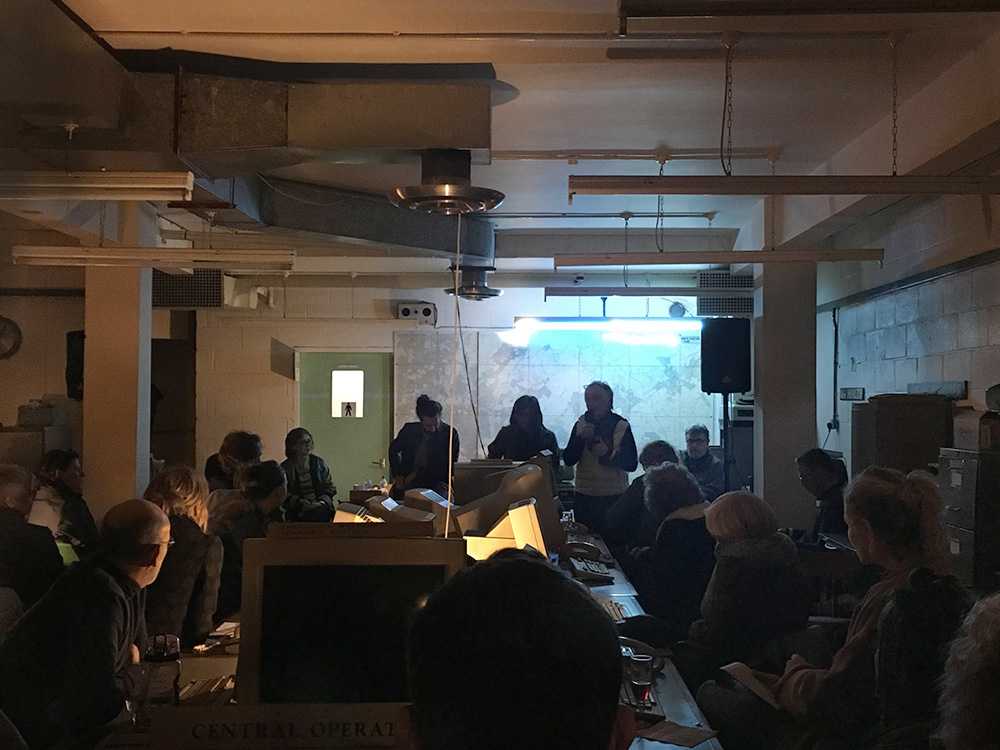

The panel, chaired by Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley, was part of the festival’s Nuclear Option day at the Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker, a twisted network of dimly lit hallways and musty rooms that lie beneath a field.

Around 75 attendees gathered on March 25 to listen to Index’s panel and attend other workshops, screenings and performances part of the festival. Everyone at the festival was free to roam the enormous bunker and walk amongst Cold War history.

Passing signs that instructed people to “use water sparingly” and dusty machines that co-ordinated evacuation procedures, attendees eventually made their way to a desk-lamp lit room and were seated at long desks with old, monochrome computers.

Looking at the current state of propaganda, Bartlett said “everything has become more emotional and gut-driven,” adding that politics has not become as informed as people had hoped, but now become “heuristic because people are just showered with information”.

Aaronovitch called the inundation of information the “age of cacophony”.

What is emerging, according to Bartlett, is a “horrible new form of soft surveillance that has encouraged a great conformity among people”.

Xinran said China’s current propaganda, especially on social media, along with party control of education and the legal system has led to “one voice” in China, despite age gaps, class, education and geographical residence.

The author talked about her past experiences with censorship and Chinese propaganda when she worked on her radio show in China. She explained that there was a list of restrictions she had to abide by, these included never mentioning the British media, Western religions or love and relationships. The author said during her show she was able to tackle subjects that were previously taboos on Chinese radio.

“My work was stopped for three months when I spoke about homosexuality,” said Xinran. “This type of censorship was very strong until 1997, but it has now escalated to constant censorship, due to social media.”

Looking at the future of propaganda and its direction, Bartlett added that he can “see much more reliance on coercive digital types of surveillance being absolutely necessary just to maintain some type of law and order in society, especially online, which could make us a much more authoritarian society”.

This led Bartlett to predict that “already authoritarian countries are going to become much more so, and already very free countries are going to become even more free to the point where it might collapse”.

He believes we are shifting to a “Huxleyan society,” which Aaronovitch called the “algorithmic society”. Both felt one big question was, who governs the algorithms?

Aaronovitch noted that it depended on who was controlling the algorithms, saying that if the EU requested that Google to reveal its algorithms, it would be problematic; however, governmental algorithms used for policing in a democratic society were essential.

With reference to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which was mentioned numerous times during the panel, Bartlett noted that the worry over “Cambridge Analytica’s 5,000 data points on every single American doesn’t compare to what’s coming”.

“We are going to be creating a lot more data in the future,” said Bartlett. “And it is going to be shared and it is going to be used by political actors.”

Aaronovitch advised the audience that the best way to combat propaganda is to ask yourself, “‘Am I wrong?’. The point is to ensure no one is “completely blinded by initial preferences”.

Similar to Aaronovitch’s warning to predisposed biases, Xinran calls for “independent thinking,” and equated the consumption of information with eating.

“In Chinese we say you become what you eat,” said Xinran. “And your brain is the same way. You become what you are by what you believe”.

Hats off to @EssexBookFest! An incredible day at the Secret Nuclear Bunker. Brilliant discussion with @IndexCensorship, @JamieJBartlett, @DAaronovitch, @londoninsider and #Xinran, topped off with a silent disco of music banned from Estonia, with obligatory gherkins and vodka 👍 pic.twitter.com/HVtfrVDRb1 — Radical ESSEX (@RadicalEssex) 26 March 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522237614911-7109bbff-bdcf-1″ taxonomies=”2631″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Mar 18 | Index in the Press

There were 1,089 verified reports of limitations to press freedom in Europe in 2017, with a majority of violations coming from official or governmental bodies, according to the Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform. Read the full article.

28 Mar 18 | Press Releases

Europejskim Centrum Wolności Prasy i Mediów (ECPMF) wraz z Międzynarodowy Instytut Prasowy (IPI) uruchamia dziś fundusz wielkości 450 000 EUR w celu wspierania transgranicznego dziennikarstwa śledczego.

Europejskim Centrum Wolności Prasy i Mediów (ECPMF) wraz z Międzynarodowy Instytut Prasowy (IPI) uruchamia dziś fundusz wielkości 450 000 EUR w celu wspierania transgranicznego dziennikarstwa śledczego.

http://www.ij4eu.net/

Fundusz „Investigative Journalism for Europe” (#IJ4EU) ma na celu rozwój i zacieśnianie współpracy pomiędzy dziennikarzami i pokojami prasowymi w Unii Europejskiej w zakresie ujawniania spraw w interesie publicznym i o znaczeniu transgranicznym. Środki mają wspierać prace dochodzeniowe odzwierciedlające rolę mediów, jaką jest działalność strażnicza, oraz pomagać społeczeństwu w pociąganiu do odpowiedzialności przedstawicieli władzy w związku z ich działaniami i zobowiązaniami. W ten sposób pomoc ta stanowi część starań na rzecz budowania trwałości demokracji i rządów prawa w UE.

Funduszem będzie zarządzał IPI, który tworzy globalną sieć redaktorów, dyrektorów medialnych i czołowych dziennikarzy broniących wolności prasy od 1950 r.

W 2018 r. o dotacje do maks. kwoty 50 000 EUR mogą wnioskować transgraniczne zespoły reporterów śledczych i/lub redakcje śledcze z co najmniej dwóch państw członkowskich UE na prowadzenie prac dochodzeniowych w sprawach o znaczeniu transgranicznym i ważnych z punktu widzenia interesu publicznego.

Celem proponowanych projektów musi być ujawnienie nowych informacji. Wnioski mogą także składać już istniejące zespoły dziennikarzy śledczych lub zespoły utworzone do celów realizacji projektu #IJ4EU. O fundusze mają także prawo ubiegać się osoby, które prowadzą jeszcze nieukończone prace dochodzeniowe w celu ukończenia artykułu do publikacji. Do składania wniosków zachęcamy zwłaszcza zespoły dziennikarzy lub redakcje spoza stolic lub największych miast lub z krajów, w których z dziennikarstwem śledczym wiąże się szczególne zagrożenie.

W programie zostanie uwzględnione przekazanie środków na wszystkie platformy, w tym druk, media nadawcze, media internetowe, filmy dokumentalne oraz reportaże wieloplatformowe.

Aby się zakwalifikować, autorzy muszą podjąć starania opublikowania (i udostępnienia w formie do opublikowania) proponowanych projektów w szanowanych serwisach lub platformach informacyjnych w co najmniej dwóch państwach członkowskich UE do 31 grudnia 2018 r.

Termin przesyłania wniosków upływa 3 maja 2018 r., czyli w Światowy Dzień Wolności Prasy. Wnioski należy złożyć w języku angielskim. Wnioskodawcy będą musieli przedstawić szczegółowy opis projektu, informacje na temat zespołu dziennikarzy śledczych, plan badań i publikacji, budżet i ocenę ryzyka.

Niezależna komisja wybierze projekty, które otrzymają fundusze, aby zawrzeć umowy ze wszystkimi zwycięskimi wnioskodawcami do 15 czerwca 2018 r.

Wnioski można składać na stronie internetowej funduszu. Znajdują się na niej także pełne informacje na temat kwalifikowalności, wniosków i procesu selekcji.

„Dziennikarstwo śledcze, które spełnia istotną rolę w każdej funkcjonującej demokracji, poddawane jest presji w całej UE” — powiedziała Barbara Trionfi, dyrektor wykonawcza IPI. „Przekazywanie środków finansowych na projekty o charakterze dochodzeniowym to sposób, który pomaga zagwarantować dotarcie do opinii publicznej informacji o sprawach, takich jak korupcja, przestępstwa finansowe, łamanie praw człowieka i szkody wyrządzone środowisku naturalnemu”.

Dodała: „Obecnie takie prace dochodzeniowe rzadko ograniczają się do jednego kraju, zatem niezbędna jest współpraca transgraniczna zespołów dziennikarzy w zakresie takich tematów. Jesteśmy dumni, że #IJ4EU będzie szansą na realizację takiego celu”.

For any questions, please contact:

Javier Luque

Head of Digital Media

IPI

Email: [email protected]

Tel.: +43 1 5129011

28 Mar 18 | Awards, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/eqJSvqcp968″][vc_column_text]The women behind Open Stadiums risk their lives to assert women’s rights to attend public sporting events in Iran. It’s a daring campaign which challenges the established Islamic order of Iran, and engages women in an issue many human rights activists have not in the past thought important.

Currently in Iran women face many restrictions on using public space. Swimming pools, schools, sports hall and even parks are gender segregated.

But the most potent example of their banishment from public life is that they are prohibited from going to popular sporting fixtures where men compete.

One of the successes of the Open Stadiums campaign has been to build the awareness of this as an issue.

Iran particularly enjoys competing in, and hosting international football and volleyball tournaments, and the Open Stadiums campaign has used Iran’s desire to take part in international competition to challenge the government’s ban on women attending events. In theory international sporting bodies do not allow member nations to use discriminatory practices during matches.

The campaigners face many difficulties. The organisers are worried that as their campaign becomes more successful, they will be identified and tracked. They cannot expand their campaign because they fear any foreign funds they receive will lead to then being identified and jailed, as the Iranian government continues to stifle dissent of any kind. The Iranian regime has a history of putting women’s rights activists under pressure.

Despite the difficulties and fears, 2017 has been a successful year for the Open Stadiums campaign. But the success of the group has put them increasingly in the spotlight and therefore heightened the risk for them.

In May, the group used the slight easing of restrictions on public debate during the presidential election campaign to publish 21 demands for women and specifically pushed for women to be able to use public spaces and go to stadiums.

In May, the group used the slight easing of restrictions on public debate during the presidential election campaign to publish 21 demands for women and specifically pushed for women to be able to use public spaces and go to stadiums.

In September, the world’s media covered the fact women, despite having tickets, were refused entry to the football world cup qualifier between Syria and Iran in Tehran.

Two things this year have changed according to Open Stadiums. First, men and women in every match now complain about the ban on women at stadiums. They have been made to feel aware of the discrimination and it is talked about it a lot on social media. Second, MPs and people in power are beginning to talk about women’s rights to attend sports events in a way that would have been taboo before.

“I was happy down in my heart, especially when I read about the other nominees,” said Open Stadiums. “They were such great campaigns and people. I hadn’t heard of them before, and it was amazing to see how many individuals in this world are doing works not for more money but for better days for other people and society. This nomination gave me strength – yesterday when I was at risk of being arrested, I was thinking if i get arrested i know some people at least know about my passion and works i did these years.”

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460×490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522067393647-a5588697-4f78-2″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Mar 18 | Africa, Artistic Freedom, Burkina Faso, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

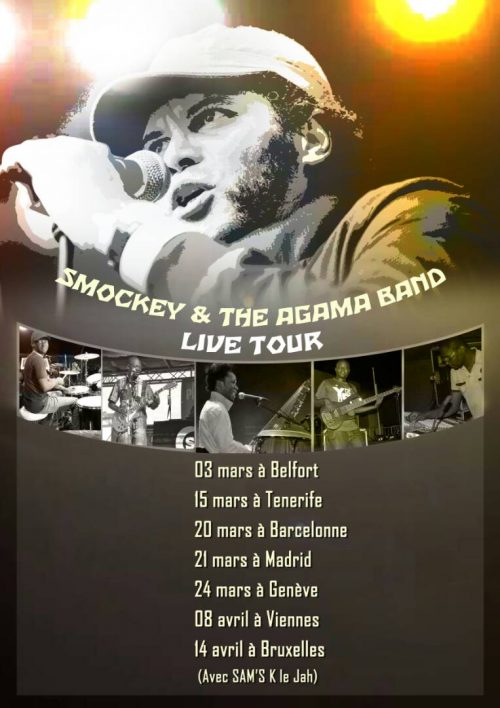

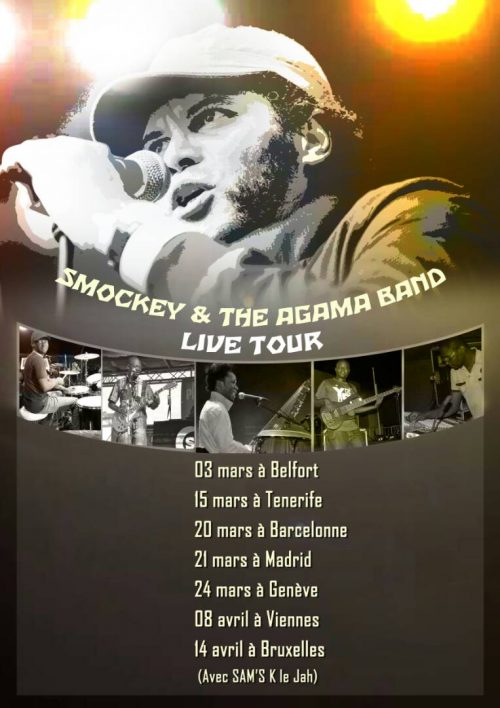

Music in Exile Fellowship Winner Serge Bambara, aka Smockey (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

On 3 March in Belfort, France, Burkinabe rapper and activist Smockey began a two-month long European tour, despite having his studio destroyed twice in recent years. The rapper, whose given name is Serge Bambara, was the inaugural Index on Censorship Music in Exile Fellow in April of the same year. Just three months after the awards, his recording studio, Studio Abazon, was wrecked in a devastating fire.

“All my music files since 2001, including my master tapes and those of my productions and clients, were lost,” Smockey told Index in September 2016. Two years on, it remains unclear how the fire began.

Smockey’s studio was also bombed in September 2015 by armed forces loyal to Burkina Faso’s former president Blaise Compaoré. This was a vengeful attack for his political activism and music critical of Compaoré’s regime.

Despite these aggressive and censorious acts, Smockey continues to record and perform, combating different forms of injustice with each track. As the founder of the grassroots political movement Le Bilai Citoyen, which helped to oust Compaoré, he often promotes the progressive ideas of Burkina Faso’s former socialist leader Thomas Sankara. The Sankarist ideology involves advocating for women’s rights, fighting corruption and imperialism, and upholding the integrity of Burkinabe people, all of which are reflected in Smockey’s lyrics. La Bilai Citoyen translates as the “the citizen’s broom,” which is “a tribute to Thomas Sankara, who organised weekly street-cleaning sessions,” Smockey told the BBC.

In March 2018 Smockey told news website Africa is a Country that Sankara’s image was that of “simplicity, modesty, and integrity … a model for anyone aspiring to manage public property”. He also noted that Sankara had the “courage and determination to build a Burkina Faso of social justice and inclusive development.”

Although the uprising of 2015 was successful in ridding Burkina Faso of an oppressive twenty-seven-year regime, Smockey is not an enthusiastic supporter of the country’s current government led by the progressive former opposition leader Roch Marc Christian Kaboré. Smockey is still a watchdog for human rights violations within his country. “The ones who were our friends before the revolution can be our enemies today,” he told Quartz Africa in July 2016. “We helped them have this power, but we are not friends because we are still sentinels.” For example, his song Tomber la Lame takes aim at widespread Female Genital Mutilation throughout Africa.

Despite multiple attempts to stop his political and artistic expression, Smockey continues to create and share his music globally. Over six weeks he will perform throughout Europe, finishing his tour in Brussels, Belgium, on 14 April.

Smockey’s European Tour Dates and Locations 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522161604778-9ae9ecbc-682f-8″ taxonomies=”8072″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Mar 18 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Doughty Street International’s Media Defence Panel invites you to join a breakfast seminar on freedom of expression and the protection of journalists and human rights activists in Egypt. Hosted in association with Index on Censorship, we will be joined by a representative of the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, Egypt (ECRF), nominees for this year’s Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Campaigning.

ECRF is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in Egypt. It provides advocacy, legal support and campaigning expertise to draw attention to human rights abuses taking place under the rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. ECRF plays an important role in documenting cases of enforced disappearance and arrests during protests, which are not reported in the heavily censored local media, and in providing legal help for the families of those detained and disappeared. Twice last year ECRF’s headquarters was raided by security forces and two staff members were arrested.

ECRF says: “Our main goal to achieve in the future, which is stated in our mission, is to empower individuals to acquire their rights, promote a culture of democracy in the Egyptian society, and expand human rights to every home in Egypt.”

The seminar will involve a panel and roundtable discussion, including a representative of ECRF; Jodie Ginsberg, Index on Censorship; and Jeremy Dear, Deputy General Secretary of the International Federation of Journalists.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”74586″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99393″ alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”97988″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Tuesday 17 April 2018 8:15-9:45am

Where: Doughty Street Chambers, 54 Doughty Street, London WC1N2LS (Directions)

Tickets: Free. Registration required via Eventbrite.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Mar 18 | Index in the Press

In the last year or so, conversations about inequality have levelled up, but the tech industry hasn’t been critiqued as majorly just yet. A recent global study revealed that just 9 per cent of IT leadership roles are given to women, whereas this year’s World Economic Forum predicted that the industry’s gender imbalance would actually worsen between now and 2026. One woman looking to combat this is Fereshteh Forough, founder and CEO of Code to Inspire. After unexpectedly finding herself selected for a Computer Science degree at university, she went on to become a professor and later sought to share her skills with underprivileged women. Read the full article.

Last year, Team 29 lawyers took on the Russian state to find out the fate of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust, but was captured by Soviet intelligence, placed in the Lubyanka prison and never seen again.

Last year, Team 29 lawyers took on the Russian state to find out the fate of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust, but was captured by Soviet intelligence, placed in the Lubyanka prison and never seen again.

In May, the group used the slight easing of restrictions on public debate during the presidential election campaign to publish 21 demands for women and specifically pushed for women to be able to use public spaces and go to stadiums.

In May, the group used the slight easing of restrictions on public debate during the presidential election campaign to publish 21 demands for women and specifically pushed for women to be able to use public spaces and go to stadiums.