17 Jan 18 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Yesterday marked three months since the murder of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Gathering outside the Maltese embassy in Malta House, London, members from Index on Censorship stood with seven other free speech and criminal justice organisations to mark the anniversary and call on the Maltese government to ensure justice is served. I spoke with Hannah Machlin, project manager for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform, Cat Lucas, programme manager for English Pen’s Writers at Risk programme, and Rebecca Vincent, UK bureau director for Reporters Without Borders for this special podcast.

During the vigil, participants left bay leaves — which in Greek mythology are a sign of bravery and strength — outside the embassy in a sign of solidarity with supporters in Malta, while a statement from Caruana Galizia’s family was read out.

Caruana Galizia was killed on 16 October 2017 when a bomb placed under her car exploded as she was leaving her home in Bidnija, Malta. Sixteen days prior to the fatal attack, Caruana Galizia filed a police report saying she was being threatened.

Through her investigative journalism career, Caruana Galizia exposed corrupt politicians and other officials, uncovering a number of corruption scandals in the Panama Papers. Caruana Galizia also investigated links between Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat to secret offshore bank accounts, to allegedly hide payments from Azerbaijan’s ruling family. Her work on government corruption also led to early elections in Malta in June 2017.

At the time of her death, Caruana Galizia was subject to several libel suits and counts of harassment. Her assets were frozen in February 2017 following a request filed by Economic Minister Chris Cardona and his EU presidency policy officer Joseph Gerada.

Her murder was condemned by many from the international community, with a previous vigil held on the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists, where nearly 60 free expression advocates gathered, calling for justice and an open and transparent investigation into her death.

Malta is currently ranked 47th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ 2017 World Press Freedom Index, and 47th out of 176 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index 2016.

Seven reports of violations of press freedom were verified in Malta in 2017, according to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project. Five of those are linked to Caruana Galizia and her family.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516205516926-5b43be63-70a3-7″ taxonomies=”18782″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Jan 18 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Uncategorized

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

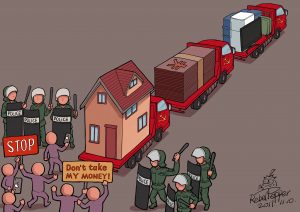

Last year was a bleak one for press freedom in Hungary. A series of transactions saw the purchase of every local newspaper — more than 500 in all — by businessmen close to the government. Papers like Somogyi Hírlap have become reliable trumpets for the government with a biased and centralised editing team in charge of political stories.

Public media has been broadcasting government propaganda for many years and the few remaining independent online media outlets have a limited reach. Many Hungarians living in the provinces have no access at all to news critical of the government and the ruling party, Fidesz.

But the government’s grip on the flow of information is being challenged by a movement resembling the underground “samizdat” publications of the Soviet Union known for skirting government censorship. “While in larger cities we use term ‘samizdat’ ironically, in small communities our readers actually perceive our newspaper as an illegal publication distributed without the consent of those in power,” János László, the leader of the Nyomtass Te Is (Print Yourself) movement, tells Mapping Media Freedom.

“Our first priority is to help people access news that is censored in the newspapers, TV stations and radio stations close to the government,” László, a former newspaper editor says. “There are still a few independent newspapers and online news websites that work honestly, but they have a limited reach. Our goal is to provide people living in the countryside with points of view other than the severely biased and the unscrupulous propaganda.”

The Nyomtass Te Is editorial team provides a weekly overview of the independent press, selecting stories from outlets such as a 444.hu and merce.hu which aren’t very well known in rural areas, about poverty, corruption, the state of the education and the health system, and rewrite them into short, easily understood articles. Page four of each publication is reserved for local news, where local activists and journalists can suggest pieces. One such article, written by an anonymous author, broke the news of Tibor Balázsi, a former press aide of the mayor of Miskolc, becoming the editor-in-chief position at a local newspaper, Észak-Magyarország.

Activists edit and lay the articles out on A4 pages. These pages are then printed in 50 different locations across the country, put in mailboxes, handed out to people on the street and at bus stations, and left in public places.

The publication is uploaded to the movement’s website, where it is downloaded and printed by the activists who distribute the newspaper. Because the whole process is decentralised and anyone can download and print the newspaper, it is difficult to know just how widely circulated it is, but, according to László, 5,000-10,000 copies are printed weekly. In a city like Miskolc, around 3,500 copies are distributed weekly, while in other places numbers are in the dozens.

“Right now we are present in more than 50 places,” László says. “Our goal is to start from county towns, and from there, to reach the smallest villages. As of January 2018, we have local partners and activists in every county.”

When his crackdown on media freedom is criticised, prime minister Viktor Orbán usually argues that one can publish anything in Hungary, so the press is free, László says, pointing out that press freedom also means a citizen’s right to easily access diverse and comprehensive information regarding public affairs.

The right to be informed is even guaranteed by the Hungarian constitution, but the majority of people living in rural areas still have no access to information other than public media, local newspapers edited by the local government and county newspapers under government control. Every city council publishes a newspaper. Because the most city councils have a Fidesz majority, and the mayor is also from Fidesz, these newspapers are totally biased towards the party.

Unsurprisingly, then, reactions from readers on Nyomtass Te Is’s circumvention efforts are almost always supportive. “Since we started, we have received emails and Facebook messages on an almost daily basis. Most of them are receptive to the idea, and only a small fraction contain anything negative. We receive many ideas on how our publication can be improved and what stories we should cover. We increased the size of our fonts after receiving complaints about readability.”

According to the editor, until now there have been no attempts to their work. “However, in small settlements, our activists are distributing copies of Nyomtass Te Is only at night and in secret.”

The movement is functioning without big donors. Instead, it relies on a lot of voluntary work and small private donations of around of 5-10 thousand forints (€15-30). The money is spent almost exclusively on printing.

As for the future, they are planning to apply for the funding opportunity titled Supporting Objective Media in Hungary by the US. Department of State, which would mean a funding of $700,000 for media operating outside the capital in Hungary to produce fact-based reporting.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516198972987-f974cdff-ca3f-7″ taxonomies=”2942″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Jan 18 | Index in the Press

A cross party group of six MEPs have asked the European Commission to introduce legislation protecting independent media against intimidating lawsuits that attempt to bully media into submission. Read the full article

17 Jan 18 | Index in the Press

It wasn’t only the EU nomenklatura who had their noses put out of joint in June 2016, when the British people rudely reminded the Euro-emperor of his embarrassing lack of clothes. Many members of the House of Lords, one suspects, equally resented the ordinary electors’ failure to vote as instructed by their betters, and the backing given to them in this refusal by a raucous, outspoken and undisciplined press that didn’t give two hoots for the views of established politicians. Read the full article

17 Jan 18 | Index in the Press

A TOXIC COMBINATION OF MISINFORMATION, hate speech, and online harassment is pushing several European countries to take action against social networks like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. But some believe their actions—however well-intentioned—run the risk of stifling free speech and putting dangerous restrictions on freedom of the press. Read the full article

16 Jan 18 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Around seven free expression and anti-corruption groups, and other supporters gathered in London today to remember investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia three months after her tragic murder in Malta, and to reiterate calls for justice in her case.

Caruana Galizia was killed on 16 October 2017 when a bomb placed under her car exploded as she drove away from her home in Bidnija, Malta. A specialist in investigating corruption, her work included exposés of the shady secret deals, uncovered in the Panama Papers, that show how politicians and others hide illicit wealth behind secret companies. Her allegations about governmental corruption led to early elections in the country in June 2017.

“We gathered to honour a remarkable woman and courageous investigative journalist. We gathered to show the Maltese authorities and the international community that we will not forget Daphne Caruana Galizia, and we will not rest until all those who planned and carried out her attack are brought to justice. We gathered in support of the very principle of press freedom, as an attack against a journalist anywhere is an attack on journalism itself,” said Rebecca Vincent, UK Bureau Director for Reporters Without Borders.

“The corruption Daphne Caruana Galizia exposed affects people across Europe, and as Europeans, we must show solidarity with her family and stand up for the truth. Justice requires not just punishing those guilty of her murder, but also ensuring that her investigations are widely read, both in Malta and across Europe. European leaders must come together to ensure there is no impunity in this case. If not, they send a chilling message that those standing against corruption may be silenced,” said Katie Morris, Head of Europe and Central Asia for Article 19.

“Until all the perpetrators, including possible masterminds, behind the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia are fully prosecuted, journalists in Malta will work in fear. The UK government must do all it can to ensure this case receives the attention it requires and that, like so many other cases of journalists murdered around the world, justice is not denied,” said Elisabeth Witchel, Impunity Campaign Consultant for the Committee to Protect Journalists.

“Today we come together to pay tribute to Daphne Caruana Galizia and to stand in solidarity with her family. Daphne’s murder was an attempt to silence her but we will not allow that to happen. We will continue to share her words and her work, and to call for a full and impartial investigation into her death,” said Antonia Byatt, Interim Director, English Pen.

“Daphne Caruana Galizia’s heinous murder has cemented a new climate of fear and uncertainty for journalists, threatening the future of free speech in Malta. On the three-month anniversary of Caruana Galizia’s death, we remember her brave and vital work which continues to hold the Maltese authorities accountable. We hope the arrests of her alleged attackers are the run-up to an independent and fair trial to ensure this will not be a grave case of impunity,” said Hannah Machlin, Mapping Media Freedom Project Manager for Index on Censorship.

“Daphne Caruana Galizia’s reporting courageously exposed organised crime and political corruption in Malta. It is vital not only that her terrible murder be fully investigated and those responsible be brought to justice, but also that her legacy in Malta continues, and that corruption and impunity there be rooted out. By gathering to remember her today, we reiterate that those who expose corruption should be protected, not intimidated”, said Patricia Moreira, Managing Director, Transparency International.

Co-sponsors of the London vigil included ARTICLE 19, the Committee to Protect Journalists, English Pen, Index on Censorship, Pen International, Reporters Without Borders, and Transparency International. Participants read a statement from Caruana Galizia’s family and wrote messages on bay leaves in solidarity with her supporters in Malta.

Malta is ranked 47th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ 2017 World Press Freedom Index, and 47th out of 176 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index 2016.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516117019985-986a456a-54fe-4″ taxonomies=”18782″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Jan 18 | News and features, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”As China’s economy slows, an unexpected group has started to protest – the country’s middle class. Robert Foyle Hunwick reports on how effective they are”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

China’s middle class protest, Rebel Pepper/Index On Censorship

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Park Avenue, central Beijing, is known for its luxurious serviced apartments, landscaped gardens and Western-style amenities, certainly not its dissident population. Yet, strolling past the compound one weekend, I was surprised to see a protest in progress.

A small group of around two dozen had assembled with signs and were milling around outside a locked shop, arguing with a harassed-looking man in the Chinese junior-management uniform of white shirt and belted black trousers. The cause of all the chaos: a swanky gym that had opened in the gated community a few months before, promising unparalleled 24-hour access to upscale fitness machines and personal trainers, had used a recent public holiday to sell all its equipment and, apparently, make off with everyone’s membership fees. Now a dispute was in full swing over who was going to take responsibility for this fiasco. The building management, who presumably had vetted the gym? The police? The residents?

The protest was a rare sighting in the capital of a country where free speech has always been tightly controlled by the government, and has become almost completely stifled under the current leader, Xi Jinping. Xi formally enters his second five-year term as general secretary, state president and “core” of the Chinese Communist Party in March, and fear for the future of political freedom and protest is at an all-time high. That paranoia is most acutely felt in the most unlikely of quarters, the main beneficiaries of the country’s economic prosperity, the Chinese middle class.

For those living just across the way, the uproar over the gym provided a rare piece of street theatre. This audience of weather tanned men and women from the country’s interior are the ones who run the market stalls, taxis and tool shops that skirt the towers. Even in central Beijing, these kinds of cheek-by-jowl living arrangements are still fairly common. Migrants run businesses out of ramshackle stores, leading hardscrabble lives beneath grandiose skyscrapers such as those in Park Avenue, where the well-heeled residents’ biggest concern is usually which international summer camp they should choose for their children.

Yet this poorer demographic is declining in China’s most-developed urban areas. Unregistered workers are being steadily forced from the cities whose growth they once spurred, ejected by implacable officials who often use passive-aggressive methods (erecting brick walls; suddenly enforcing long-stagnant municipal regulations) to make their working lives untenable. Blue-collar migrants have little leverage to protest these decisions, and are moving away, leaving behind middle-class homeowners who have no interest in complaining on their behalf. Indeed, most are happy to see them gone. The middle class prefer to consider themselves safe, content in the knowledge that their own rights are secured by lease- holds, law and lucre. All they have to worry about are gym memberships.

This is, or at least was, the essence of the unspoken contract that emerged in the bloody aftermath of the disastrous protests in Tiananmen Square during the summer of 1989. Prior to that, “the demands of politically active urbanites were aimed squarely at the national leadership and national policy – for political liberalisation, a free press, and fairness in local elections”, noted Andrew Walder in Untruly Stability: Why China’s Regime Has Staying Power.

After 1989, former leader Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms dramatically shifted the landscape to one that focused on individual prosperity at the expense of any greater good. Stay out of the politics, the government seemingly implied, and we will stay out of your lives – a “deal” that helped drive one of the greatest booms in history. Like any agreement left unspoken, though, this pact has turned out to be worth rather less than the paper it was written on.

Now as growth slows and debts accumulate, the cracks are growing more evident in the propaganda façade of peaceful prosperity, one in which absurdist posters increasingly plead “Every day in China is like a holiday”, while uniformed soldiers patrol the capital’s streets and whole neighbourhoods are torn down without warning.

Some now refer to a “normal country delusion”, the comforting myth that being a law-abiding, middle-class citizen is a bulwark against authoritarian anger. The Germans have another word for it: mitläufer – getting along to get by; the hope that obeying rules protects oneself in the event of accidentally breaking any.

The complacency of this particular fantasy was blown apart, in spectacularly literal fashion, by the chemical explosion that occurred in the coastal city of Tianjin in the early hours of 12 August 2015. Similar blasts happen on a semi-frequent basis throughout China, usually the result of muddled regulations, lax oversight and complicity between officials, developers and businessmen. Hidden in the country’s vast interior, these disasters usually pass without comment, with protests swiftly stifled and any cover- age strictly limited to terse, state-approved reports. According to the New York Times, “68,000 people were killed in such accidents [in 2014]…most of them poor, powerless and far from China’s boom towns”.

Tianjin – a city bristling with international enterprises, and easily reachable from Beijing via high-speed rail in just 30 minutes – was a very different affair. Reporters from the Chinese and international media descended on the scene within hours and the story was carried for days, providing an almost unheard of level of scrutiny.

The government’s disaster-management skills were on full display: untrained junior firefighters sent to tackle a chemical blaze for which they were fatally unequipped; a series of disastrous press conferences; officials sacked and replaced on an almost daily basis; then, finally, a total media shutdown.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”They’ve taken everything from us. We’ll take everything from them.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

But amid the disarray, the overriding narrative concerned the thousands of middle- income homeowners who had been killed, injured or displaced as a result of zoning irregularities that allowed 11,000 tonnes of highly volatile chemicals to be stored next to the new (and now obliterated) residential blocks within the blast zone. As one blogger observed, these were the people who “maintain a noble silence on any public incident you’re aware of. On the surface, you look no different from a middle- class person in a normal country.”

Writing on microblog service Weibo, user Yuanliuqingnian noted that when these same apolitical families gathered near the site, first to mourn, then – as the official silence grew deafening – to protest their treatment, an un- fortunate realisation set in. They “discovered they’re the same as those petitioners they look down on… kneeling and unfurling banners, going before government officials and saying ‘we believe in the Party, we believe in the country’.

The homeowners realise, much to their embarrassment, that, after an accident, there’s really #nodifference between us and them.”

A year on, Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao reported that the treatment of these middle-class victims remained taboo: family members of the firefighters were arrested for mourning their dead sons, while a collective of homeowners protested anew that the government had still not compensated them for their lost properties. They’d become the very people they disdained: what older Chinese called yuanmin –“people with grievances”.

In some instances, government policy unwittingly forged these resistances. I met one family in Shanghai whose home had been demolished for the 2010 World Expo. After months of protest, local officials ensured that both parents lost jobs or promotions and their two sons, in their late teens, were denied graduate placements. The result was four enraged adults with nothing to lose. “They’ve taken everything from us,” the mother vowed. “We’ll take everything from them.” Such outbursts echo the sea change in mainland protest, from the political to the personal. Today’s yuanmin “invoke national law and charge local authorities with corruption or malfeasance” as Walder observed.

“Protest leaders see higher levels of government as a solution to their problem, and their protests are largely aimed at ensuring the even-handed enforcement of national laws that they claim are grossly violated.”

These grievances are still highly risky and liable to be dispersed (or, worse, ruthlessly punished), and are only occasionally and specifically effective. Sometimes, officials might be motivated by political imperatives to quickly mollify any protesters; sometimes they might be compelled, for the same reasons, to thoroughly quash them.The result is that, despite being afforded exclusively bourgeois privileges such as healthcare and education, China’s middle class exists “in constant fear of losing everything”, writes Jean-Louis Rocca in his book, The Making of the Chinese Middle Class.“They live in an unstable world, and they are never sure where they are on the social ladder. They imitate the bourgeoisie’s life- style and they strive to avoid falling into the category of ‘workers’.”

“Zhang”, a Shenzhen-based journalist who asked for a pseudonym for fear of official repercussions, blamed the “growing pressure in Chinese society and the instability of government policies”. In the case of housing, “[some] had already scraped together barely enough to buy a house, now they had to come up with more money in the short term. In this way, even though you are ‘middle class’, you don’t quite feel like you are living the life a middle- income person deserves”.

Exacerbating matters is the lack of options available to those who have been wronged, swindled or otherwise denied their supposed rights. “Some don’t really know what options they have,” Zhang told Index. “Some are aware they can’t really do anything, in fear they might lose more of what they have.”

Ingrained anxieties are apparent in the issues that do force members of the smart-phone-clutching middle class off their We- Chat groups – where posts about “sensitive” issues are quietly erased by sophisticated censorship algorithms – and into the less- forgiving arena of public protest.

In May, dozens protested outside Beijing’s housing authority against new regulations that prevent homeowners buying multiple apartments, saying that the rules trampled on their property rights. There were similar, and partially successful, demonstrations in Shanghai the following month over residen- tial zoning rights. In this case, the municipal authorities chose to blame property develop- ers as they backed down, accusing them of “distorting the policy”.

In July, thousands staged the biggest protest in Beijing in years, after a pyramid scheme they’d invested in was declared illegal, with millions in funds frozen.

The response to the disruption was harsh. After detaining 64, police said they had “released some who created minor harm, but made good confessions. However, there will be a crackdown on those plotting and inciting the gathering.” Some are realising that this is often the case. Many others, though, are in denial about the insecurity of their wealth. Comparing Chinese society to an “atmospheric tank”, scholar Zeng Peng warned, in a paper on protest, that “to prevent the gas tank bursting, on the one hand [the government] should stop the production of grievances, on the other hand repair the safety valves”.

There have never been strong systemic means for resolving disputes in China, other than by drawing public attention. In imperial eras, yuanmin would bang gongs or throw themselves in front of visiting envoys from Beijing to plead their case, believing that the emperor’s officials would be outraged by the local rot. Today, the commonest resort for everyday yuanmin is to take to social media to blow off steam or report malfeasance.

Those without the audience or the means might take things further, travelling to Beijing to lodge a petition of complaint, an archaic and ineffectual process that dates back to ancient times, and whose continued necessity is an embarrassment for Beijing. As if recognising this, while fearing the consequences of addressing it fully, the current administration seems intent on shearing off access to any valves they don’t completely control, even while it struggles to quell the multiplying means of production.

Even when protests seem successful, the effects can prove deleterious in the long term. As Tianjin proved, the middle classes may find their calls for change ignored, the rules changed abruptly or their actions punished, just like their poorer neighbours. And those aggrieved Park Avenue protestors who’d demanded their membership fees back? When I returned a half-hour later, they’d disappeared too; not a single one remained, nor any sign to indicate they’d ever been there.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Robert Foyle Hunwick is a freelance journalist based in Beijing

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91419″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228908534694″][vc_custom_heading text=”The people’s horror” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228908534694|||”][vc_column_text]September 1989

Index’s Asia specialist, Lek Hor Tan, reviews why China’s human rights record has long been glossed over and looks at the history that led up to the massacre in Tienanmen Square.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89086″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422013495334″][vc_custom_heading text=”Border trouble: china’s internet” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013495334|||”][vc_column_text]July 2013

Chinese government uses sophisticated methods to censor the internet. Despite citizens’ attempts to circumvent barriers, it has created a robust alternative design.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89073″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422013513103″][vc_custom_heading text=”Stamping out the moderates ” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013513103|||”][vc_column_text]December 2013

Chinese authorities are cracking down on popular New Citizens’ Movement, even though its leaders are trying to protect rights already guaranteed under the constitution.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In homage to the 50th anniversary of 1968, the year the world took to the streets, the winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at all aspects related to protest.

With: Micah White, Ariel Dorfman, Robert McCrum[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Jan 18 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, Index in the Press

Murad Subay sees the devastated streets and bombed buildings in Yemen’s war as something more than just ruins: he sees canvases onto which he can tell stories through art. The award-winning 30-year-old street artist’s aim is to spread a message of peace during Yemen’s current crisis – and his work is having a major impact in Yemen and abroad. Read in full.

15 Jan 18 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] MEPs David Casa (EPP), Ana Gomes (S&D), Monica Macovei (ECR), Maite Pagazaurtundúa (ALDE) Stelios Kouloglou (GUE) and Benedek Jávor (Greens) have joined forces to push for EU legislation that will address and end “SLAPPs” – lawsuits intended to intimidate and silence investigative journalists and independent media by burdening them with exorbitant legal expenses until they abandon their opposition. According to the MEPs, the practice is abusive, poses a threat to media freedom and has no place in the European Union.

MEPs David Casa (EPP), Ana Gomes (S&D), Monica Macovei (ECR), Maite Pagazaurtundúa (ALDE) Stelios Kouloglou (GUE) and Benedek Jávor (Greens) have joined forces to push for EU legislation that will address and end “SLAPPs” – lawsuits intended to intimidate and silence investigative journalists and independent media by burdening them with exorbitant legal expenses until they abandon their opposition. According to the MEPs, the practice is abusive, poses a threat to media freedom and has no place in the European Union.

SLAPP was used, for instance, against investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia and is now being used against Maltese media houses by firms associated with government corruption and the Panama Papers scandal that are threatening legal action in the United States. David Casa, Ana Gomes, Monica Macovei, Maite Pagazaurtundúa, Stelios Kouloglou and Benedek Jávor stated: “In Malta we have seen that firms like Pilatus Bank and Henley & Partners that employ these practices, using American litigation, have succeeded in having stories altered or deleted completely from online archives. And investigative journalists are prevented from reporting further on corrupt practices out of fear of further legal action. But this is not just a Maltese problem. In the UK, Appleby, the firm associated with the Paradise Papers, is using similar tactics against the Guardian and the BBC.

The cross-border nature of investigative journalism as well as the tendency to pursue legal action in jurisdictions outside the EU that only have a tenuous connection with the parties justifies and requires an EU response”.

The MEPs are calling on EU Commissioner Frans Timmermans to propose an EU anti-SLAPP directive that will include:

• The ability for investigative journalists and independent media to request that vexatious lawsuits in the EU be expediently dismissed and claim compensation;

• The establishment of punitive fines on firms pursuing these practices when recourse is made to jurisdictions outside the EU;

• The se]ng up of a SLAPP fund to support investigative journalists and independent media that choose to resist malicious a^empts to silence them and to assist in the recovery of funds due to them;

• The setting-up of an EU register that names and shames firms that pursue these abusive practices.

“We are committed to the protection of investigative journalists and media freedom across the EU and will pursue this issue until anti-SLAPP EU legislation is in place,” the MEPs stated.

Thomas Gibson from the Committee to Protect Journalists stated: “SLAPP is a serious threat to journalism and media freedom. These sums of money are in no way proportionate.

Independent journalists in Malta already face enormous challenges and restrictions. critical journalism must not be stifled. In addition to pushing for full justice of the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia, the Commission needs to address the climate in which investigative journalists work in the country.”

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said: “Having a media that is free to investigate corruption and abuse of power – and free to publish the results of those investigations – is fundamental to democracy. These vexatious lawsuits – deliberately aimed at preventing journalists from carrying out such work – must be stopped.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516372688389-8d5f3054-b08d-10″ taxonomies=”1682, 14259, 18781″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Jan 18 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

London, 15 January 2018 – A delegation of global press freedom groups will undertake an unprecedented mission to the United States, reflecting concerns about threats to journalists and heightened anti-press rhetoric. The mission will coincide with the one-year anniversary of President Trump’s inauguration and will leverage the first year’s findings of the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, which will be released at an event at the Newseum, Washington D.C.

From January 15 to 17, leaders of six organisations — Article 19, CPJ, Index on Censorship, IFEX, and International Press Institute — will conduct a fact-finding visit to Houston, Texas, and the Missouri cities of Columbia and St. Louis. They will then travel to Washington for the Assessment of Press Freedom event at the Newseum on Wednesday, January 17, at 7:00 p.m. EST, and meetings with high-level policymakers on January 18 and 19.

The Press Freedom Tracker website collects data on the arrests of journalists, the seizure of their equipment, physical attacks, border stops, and other incidents.

Index on Censorship and Article 19 routinely participate in missions to countries of concern for press freedom. Recently this has included trips to Ukraine and Turkey. In 2016, Index produced a report “It’s Not Just Trump,” which highlighted the varying threats to media freedom there.

The partner organisations hope the mission will help bring attention to the deterioration of press freedom in the U.S., its impact on media freedom globally, and show solidarity with the journalist community.

Note to Editors:

Index on Censorship

Index on Censorship is a London-based non-profit organisation that publishes work by censored writers and artists and campaigns against censorship worldwide. Since its founding in 1972, Index on Censorship has published some of the greatest names in literature in its award-winning quarterly magazine, including Samuel Beckett, Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Arthur Miller and Kurt Vonnegut. It also has published some of the world’s best campaigning writers from Vaclav Havel to Elif Shafik.

Article 19

Article 19 is a human rights organisation which defends and promotes freedom of expression and freedom of information worldwide.

Media contacts:

Please contact Sean Gallagher at Index on Censorship on [email protected] or ARTICLE 19’s press team on [email protected] for further information or to arrange interviews with mission participants.

Please contact [email protected] to to obtain press credentials for the January 17 Newseum event, which will be livestreamed at 7:00 p.m. EST at www.newseum.org/event.

12 Jan 18 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Con ocasión de las elecciones mexicanas del año que viene, Duncan Tucker repasa en este reportaje de investigación para Index las amenazas que han sufrido los periodistas de este país durante la última década.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Un periodista mexicano sujeta una cadena alrededor de su boca durante una marcha silenciosa de 2010 en protesta contra los secuestros, asesinatos y violencia que sufren los periodistas del país, John S. and James L. Knight/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Pablo Pérez, periodista independiente de Ciudad de México, atravesaba en coche el estado sin ley de Guerrero con dos colegas de la capital y cuatro reporteros locales cuando los detuvo una horda de hombres armados. Pérez estaba trabajando en un reportaje sobre los lugareños a los que la violencia del narcotráfico había desplazado de la región.

«Acabábamos de dejar la zona más peligrosa y pasamos por un puesto de control del ejército, lo cual nos hizo creer que estábamos en una zona segura», narra Pérez, poco después del incidente del 13 de mayo. «Pero no: a kilómetro y medio de allí nos detuvo un grupo de 80 a 100 hombres jóvenes; muchos de ellos, armados. Registraron nuestros vehículos y nos robaron todo el equipo, el dinero y los documentos de identificación. Se llevaron uno de nuestros autos y nos dejaron con el otro. Nos dijeron que tenían informadores en el puesto de control y que nos quemarían vivos si se lo contábamos a los soldados», relata.

Pérez y sus compañeros sobrevivieron, conmocionados, pero ilesos. Otros no han tenido tanta suerte. 2016 batió el récord con 11 periodistas asesinados, y 2017 va camino de superar ese cómputo nefasto.

Los medios impresos han comenzado a introducir modestos protocolos de seguridad en una apuesta por proteger a sus empleados, mientras que el gobierno ha anunciado recompensas para quienes faciliten información sobre los responsables de asesinar a periodistas. Pese a todo, lo más probable es que estas medidas no tengan un gran impacto frente a la violencia desenfrenada, la corrupción y la ausencia de justicia imperante en el país. La narcoguerra de México ha dado cifras récord de muertes en 2017 y, con la posibilidad de que las elecciones del año que viene provoquen aún más inestabilidad, no parece que los ataques a periodistas vayan a desaparecer próximamente.

El nivel de peligrosidad varía considerablemente según la región de México a la que nos refiramos. Los ataques a corresponsales extranjeros son raros, probablemente porque acarrearían una presión internacional indeseada. Los mexicanos que trabajan en publicaciones nacionales o metropolitanas también están protegidos de la violencia, hasta cierto punto. Son los reporteros locales los que se enfrentan a los mayores peligros. Según el Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas, el 95% de las víctimas de asesinato como respuesta directa a su trabajo son normalmente reporteros de publicaciones de regiones remotas, donde el crimen y la corrupción rampantes minan el peso de la ley. Los estados sureños de Guerrero, Veracruz y Oaxaca comprenden actualmente los lugares más mortíferos, sumando al menos 31 periodistas asesinados desde 2010 en el territorio.

Pese a los riesgos a los que se expone la profesión, el periodista mexicano medio gana menos de 650 dólares al mes y recibe pocas ventajas.

«No tenemos seguro médico ni de vida. Somos vulnerables a esta violencia», dice Pérez. «Aunque los que vivimos en grandes ciudades estamos mucho más seguros que los que están en lugares como Guerrero».

Cuando visitan zonas en conflicto, reconoce Pérez, no hay mucho que puedan hacer salvo adoptar algún que otro protocolo básico de seguridad. «Todos tratábamos de mantener contacto constante con colegas en la ciudad, cosa que no era nada fácil, ya que a menudo perdíamos la cobertura del teléfono. El protocolo era no separarnos, seguir en contacto con periodistas locales y mantenernos alerta a cualquier señal de peligro».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mientras que los periodistas de la capital pueden refugiarse en lugares relativamente seguros después de trabajar en zonas peligrosas, los reporteros locales están permanentemente expuestos a las consecuencias de su trabajo. Una brutal ilustración de ello fue el asesinato el 15 de mayo de Javier Valdez, uno de los periodistas más afamados y respetados de México, en su Sinaloa natal. Valdez acababa de salir de su oficina de Ríodoce, un semanal de noticias fundado por él mismo, cuando unos hombres armados lo bajaron a la fuerza de su coche y lo obligaron a arrodillarse. Le dispararon 12 veces a quemarropa y acto seguido huyeron con su teléfono y portátil, abandonándolo boca abajo en la carretera. Su característico sombrero panamá estaba manchado de sangre.

Valdez era una autoridad en el campo de los bajos fondos de Sinaloa, la cuna del narcotráfico mexicano. También era el periodista más prominente asesinado en años. En una entrevista con Index unos meses antes de su asesinato, habló de amenazas contra su periódico y lamentaba la falta de protección por parte del gobierno. Afirmaba: «Lo mejor sería llevarme a mi familia y abandonar el país».

En las semanas anteriores a su muerte, Valdez había estado involucrado en las consecuencias de un sangriento forcejeo por el poder dentro del poderoso cártel mexicano de Sinaloa. La violencia en la región se ha disparado desde que el líder Joaquín «El Chapo» Guzmán, de terrible fama, fuera extraditado a EE.UU. el pasado año, dejando a sus hijos Iván y Alfredo luchando por el control del cártel contra Dámaso López, su ex-mano derecha.

Cuando Valdez entrevistó a un intermediario enviado por López en febrero de 2017, los hijos de Guzmán llamaron a la sala de redacción de Ríodoce y les advirtieron acerca de publicar el artículo. Ofrecieron comprar toda la tirada, pero Valdez se mantuvo en sus trece. Cuando el periódico salió en distribución, miembros armados del cártel siguieron a los camiones de reparto por Culiacán y compraron todos los ejemplares. Los colegas de Valdez sospechan que fue su decisión de publicar la entrevista lo que le costó la vida.

Adrián López, editor de Noroeste, otro periódico de Sinaloa, contó a Index que la muerte de Valdez causó «mucha indignación, rabia y miedo» en la comunidad local. Según él, el haber puesto en el blanco a una figura tan conocida envía un mensaje contundente a los periodistas y activistas de México, así como a la sociedad al completo: «Si somos capaces de matar a Javier, somos capaces de matar a cualquiera».

López también ha vivido la interferencia editorial de los cárteles. En 2010, varios hombres armados dispararon 64 veces contra las oficinas de Noroeste, en la ciudad costera de Mazatlán. Los asaltantes habían amenazado a los empleados por teléfono horas antes, instándolos a atribuir los casos recientes de violencia a un cártel rival. «Decidimos no publicar lo que ellos querían porque nuestra postura es que no se puede decir que sí a semejantes exigendias», dijo López. «Si dices que sí una vez, después nunca podrás decir que no».

López sufrió unas circunstancias similares a las de Valdez en 2014, cuando unos hombres armados bloquearon su coche en la capital estatal de Culiacán. Los asaltantes le robaron el coche, la cartera, el teléfono y el portátil y le dispararon en la pierna. Semanas antes, varios reporteros de Noroeste habían recibido amenazas y palizas mientras cubrían el caso de Guzmán y el cártel de Sinaloa.

Según López, su periódico trabaja continuamente para mejorar sus protocolos de seguridad. Noroeste emplea a abogados para denunciar todas las amenazas contra ellos a las autoridades pertinentes, y han contratado a terapeutas que faciliten ayuda psicológica a los trabajadores. «La violencia con la que tratamos día tras día no es normal», explica López. «Necesitamos ayuda profesional para entender y hablar más sobre estas cosas, sobre el trauma que la violencia nos podría ocasionar».

Más de 100 periodistas mexicanos han sido asesinados desde 2000, y hay al menos otros 23 desaparecidos. En estos últimos tres años, cada año ha superado al anterior en cuestión de asesinatos, y este podría ser el más mortífero hasta la fecha, tras los 10 periodistas asesinados en los primeros ocho meses de 2017 (hasta agosto de 23). Las autoridades mexicanas a menudo están implicadas en los ataques. Artículo 19, organismo de control de la libertad de prensa, documentó 426 ataques contra medios de comunicación el pasado año; un incremento del 7% desde 2015. El 53% de esos ataques se atribuyen a ocupantes de cargos públicos o a las fuerzas de seguridad.

Alejandro Hope, analista de seguridad, contó a Index: «Las autoridades federales no han investigado ni procesado estos casos en condiciones. Han creado un entorno de impunidad que ha permitido que prosperen los ataques a la prensa».

En julio de 2010, el gobierno fundó la Fiscalía Especializada para la Atención de Delitos contra la Libertad de Expresión (Feadle) con la intención de investigar los delitos cometidos contra los medios de comunicación. La agencia, que no respondió a la petición de Index de una entrevista, ha facilitado botones de alarma a los periodistas en peligro, les ha instalado cámaras de seguridad en casa y, en casos extremos, les ha asignado guardaespaldas. Pero hacia finales de 2016, de un total de 798 investigaciones, tan solo había logrado condenar tres autores de agresiones a periodistas.

En vista del empeoramiento de la violencia contra la prensa, el presidente Enrique Peña Nieto nombró en mayo de 2017 a un nuevo director que pudiese revigorizar Feadle. Al mes siguiente, su gobierno anunció recompensas de hasta un millón y medio de pesos (83.000 dólares) a cambio de información sobre los responsables de matar a periodistas.

Hope añadió que México ha progresado en cierta medida en lo que respecta a la libertad de prensa en décadas recientes, gracias a la proliferación de webs informativas críticas e independientes y la mejora del acceso público a información sobre el gobierno. Sin embargo, añadió, estas mejorías se han dado sobre todo en lo nacional, mientras que los periodistas de ciertas regiones operan «en un entorno mucho más difícil» a día de hoy.

Las mayores dificultades las entraña el tener que lidiar con las relaciones fluctuantes entre las autoridades locales y las bandas de narcos, dijo Hope. Citó el caso de Miroslava Breach, una respetada reportera asesinada en Chihuahua en abril de 2017 después de que investigara el vínculo entre políticos locales y el crimen organizado.

Hay poco motivo para el optimismo. México se prepara para las elecciones generales del año que viene, pero algunas campañas recientes ya se han visto perjudicadas por acusaciones de fraude electoral e intimidación. Hope advirtió de que las elecciones podrían perturbar la estabilidad de pactos existentes entre criminales y políticos, dificultando aún más el trabajo de los periodistas locales y haciéndolo más peligroso. Vaticina que la actual ola de violencia continuará durante las elecciones «porque va a haber más gente en el terreno informando sobre regiones conflictivas».

Pérez cree que la situación no va a mejorar mientras el país no aborde su cultura de corrupción e impunidad. Puso como ejemplo el caso de Javier Duarte, exgobernador de Veracruz y amigo del presidente, arrestado en Guatemala en abril de 2017 tras seis meses a la fuga. Al menos 17 periodistas locales fueron asesinados y tres más desaparecieron durante los seis años de su mandato; sin embargo, no fue sujeto a escrutinio alguno hasta que se reveló su malversación de aproximadamente tres mil millones de dólares de fondos públicos.

«¿A cuántos de nuestros colegas han asesinado sin que la fiscalía haga nada?» pregunta Pérez. «Lo más importante es apresar a todos nuestros políticos corruptos. Si el robo de fondos públicos no tiene repercusiones, ¿cómo vamos a esperar que aquellos que minan la libertad de expresión se preocupen por las consecuencias?».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

UN «WATERGATE» MEXICANO

Una investigación de Citizen Lab y The New York Times este verano ha revelado la presencia del spyware Pegasus, desarrollado por una compañía de ciberarmas israelí llamada NSO Group, en mensajes enviados a periodistas y otros objetivos. Algunos periódicos lo han bautizado como «el Watergate mexicano».

Uno de los objetivos del spyware era Rafael Cabrera, miembro de un equipo de periodistas de investigación dirigidos por Carmen Aristegui. Estos perdieron su empleo en una emisora nacional de radio tras destapar un escándalo de corrupción en el que estaban envueltos el presidente Enrique Peña Nieto y su mujer, Angélica Rivera.

Index habló con él dos años antes acerca de su cobertura del escándalo. En aquel entonces, Cabrera había comenzado a recibir unos misteriosos mensajes de texto en los que lo advertían de que tanto a él como a sus colegas podían demandarlos o encarcelarlos a causa de su investigación.

Los mensajes venían con enlaces que prometían más información, pero Cabrera, sospechando que podían contener algún virus, no los abrió.

Y estaba en lo cierto. Como se descubrió más adelante, abrir el enlace habría permitido a sus remitentes acceder a los datos de Cabrera, ver todo lo que tecleaba en su teléfono y utilizar su cámara y micrófono sin ser detectados.

NSO Group afirma que vende spyware a gobiernos exclusivamente, con la condición de que se use solamente para investigar a criminales y terroristas. Pero la investigación descubrió que Aristegui y su hijo adolescente también habían sido objetivos del spyware, además de otros periodistas, líderes de la oposición, activistas anticorrupción y por la salud pública.

Peña Nieto respondió diciendo que la ley se aplicaría contra aquellos que estaban «haciendo acusaciones falsas contra el gobierno». Más adelante, en una entrevista con The New York Times, un portavoz afirmaba: «El presidente no trató en ningún momento de amenazar ni a The New York Times ni a ninguno de estos grupos. El presidente cometió se explicó mal».

El gobierno, sin embargo, ha admitido el uso de spyware contra bandas criminales, si bien niega haber espiado a civiles. Las autoridades han prometido investigarlo.

Cabrera le contó a Index que tenía poca fe en la credibilidad de una investigación del gobierno de sus propios programas de vigilancia. También expresó su alarma ante la reacción inicial de Peña Nieto. «No está nada bien que el presidente diga que va a tomar acción penal contra ti», afirmaba Cabrera. «Se salió del guion y por un momento nos mostró al dictador que lleva dentro». DT

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

PLATA O PLOMO

Los periodistas mexicanos se las ven con todo tipo de amenazas y presiones económicas, desde los cárteles del narcotráfico hasta agentes del estado. Article 19 documentó 426 ataques contra la prensa mexicana en 2016, incluyendo 11 asesinatos, 81 agresiones, 79 actos de intimidación, 76 amenazas directas, 58 secuestros y 43 casos de acoso.

Los cárteles se han infiltrado en las salas de prensa de áreas asoladas por el crimen, y normalmente ofrecen a los reporteros a elegir entre «plata o plomo»; es decir, entre un soborno o una bala. Como el aclamado periodista Javier Valdez declaraba para Index meses antes de su asesinato, esto genera miedo y desconfianza dentro de los equipos informativos y fomenta la autocensura.

Muchas publicaciones también temen criticar al estado porque dependen en gran medida de la publicidad contratada por el gobierno. Tanto el gobierno federal como los gobiernos estatales mexicanos se gastaron aproximadamente 1.240 millones de dólares en publicidad en 2015. Las voces críticas afirman que se trata de una forma de «censura blanda», ya que las publicaciones deben vivir con la amenaza implícita de que el gobierno castigará todo tipo de cobertura desfavorable retirando su financiación. DT

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

CIFRAS CRIMINALES

-

Al menos 107 periodistas han sido asesinados en México desde 2000. Del total, 99 son hombres y 8, mujeres.

-

Han desaparecido 23 periodistas en México desde mayo de 2003 hasta mayo de 2017.

-

En 2016, el 53% de los ataques contra la prensa tuvo a cargos públicos involucrados. Entre 2010 y 2016, las autoridades investigaron 798 ataques a periodistas. Solo los autores de tres de esos ataques han recibido condena.

-

Son más de 200.000 las personas asesinadas o desaparecidas desde que comenzó la guerra antinarco en diciembre de 2006. DT

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Investigación realizada para Index por Duncan Tucker, periodista afincado en Guadalajara, México.

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista Index on Censorship en otoño de 2017.

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Jan 18 | Journalism Toolbox Russian

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”В преддверии выборов в Мексике в следующем году, в рамках специального расследования для «Индекса», Дункан Такер анализирует угрозы журналистам за последнее десятилетие. “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Мексиканский журналист одел цепь вокруг рта во время молчаливого марша в знак протеста против похищений, убийств и насилия над журналистами в стране, John S. and James L. Knight/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

ПАБЛО ПЕРЕС, независимый журналист из Мехико, ехал в беззаконном южном штате Герреро с двумя столичными коллегами и четырьмя местными журналистами, когда их задержали толпы вооруженных людей. Перес работал над статьей о местных жителях, переехавших из-за насилия, связанного с наркотиками.

«Мы только что покинули самую опасную зону и прошли через армейский контрольно-пропускной пункт, что заставило нас полагать, что мы пребываем в безопасном месте», – рассказал Перес, вскоре после этого инцидента, который случился 13 мая. «Но нет, всего через одну милю мы были остановлены на дороге группой численностью 80-100 молодых людей, некоторые из них были вооружены».

«Они обыскали наши машины и украли все наше оборудование, деньги и удостоверения. Они забрали одну из наших машин, но оставили нам другую. Нам они сказали, что у них были осведомители на контрольно-пропускном пункте и что они сожгут нас живьем, если мы будем разговаривать с солдатами», – рассказал он «Индексу».

Перес и его коллеги выжили, – шокированы, но невредимы. Другим не так повезло. 11 журналистов были убиты в рекордном 2016 году, а 2017 год видимо превзойдет это мрачное число.

Издания начали публиковать умеренные протоколы безопасности в попытке защитить своих сотрудников, а правительство недавно объявило о наградах за информацию об убийцах журналистов. Однако эти меры вряд ли окажут значительное влияние ввиду бесконтрольного насилия, коррупции и отсутствия правосудия. Мексиканская нарковойна принесла рекордное количество убийств в 2017 году и наряду с последующими летними выборами является причиной дальнейшей нестабильности по всей стране, так что нападения на журналистов вряд ли скоро прекратятся.

Уровень риска значительно варьируется на территории Мексики. Иностранные корреспонденты редко стают объектом нападений, – вероятной причиной является то, что это приведет к нежелательному международному давлению. Мексиканские национальные или столичные издания также относительно защищены от насилия. С наибольшими рисками сталкиваются местные журналисты. Согласно данным Комитета по защите журналистов, 95 % из тех, кто погиб в результате прямого возмездия за свою работу, составляют репортеры изданий, которые обычно находятся в отдаленных регионах, где верховенство права подрывается разгулом преступности и коррупции. Южные штаты Герреро, Веракрус и Оахака в настоящее время входят в число наиболее смертоносных мест, на которые приходится, по крайней мере, 31 журналист, убитый с 2010 года.

Несмотря на риски, с которыми он сталкивается, среднестатистический мексиканский журналист зарабатывает менее 500 фунтов стерлингов (650 долларов США) в месяц и получает совсем мало пособий.

«У нас нет медицинской страховки или страхования жизни. Мы уязвимы для этого насилия», – рассказывает Перес. «Хотя тем, кто живет в больших городах, намного безопаснее, чем тем, кто работает в местах как Герреро».

Перес рассказывает, что во время посещений горячих точек журналисты мало что могут сделать, кроме соблюдения основных протоколов безопасности. «Каждый из нас пытался постоянно контактировать с городскими коллегами, что было трудно, потому что часто пропадала мобильная связь. Протокол гласил – держаться вместе, поддерживать контакт с местными журналистами и быть очень внимательными к любым признакам опасности».

В то время как журналисты из столицы могут укрыться в относительно безопасном месте после сообщения об опасности, местные журналисты постоянно подвержены рискам из-за их работы. Это было жестоко проиллюстрировано, когда Хавьер Вальдес, один из самых знаменитых и уважаемых журналистов в

Мексике, был убит в его родном штате Синалоа 15 мая. Вальдес только что покинул офис «Риодоче», основанного им новостного еженедельника, когда вооруженные бандиты вытащили его из собственной машины и заставили стать на колени. Они выстрелили 12 раз в упор, а затем сбежали, прихватив телефон и ноутбук Вальдеса, оставив его лежать лицом вниз на дороге. Его брендовая панама была пропитана кровью.

Вальдес пользовался авторитетом в преступном мире в Синалоа, месте рождения мексиканской наркоторговли. И он был самым известным журналистом, убитым за последние годы. В интервью «Индексу» за несколько месяцев до убийства, он говорил об угрозах своей газете и с сожалением отмечал отсутствие правительственной защиты. Он сказал: «Самым лучшим выходом было бы взять мою семью и покинуть страну».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

За несколько недель до своей смерти Вальдес был вовлечен в эпицентр последствий кровавой борьбы могущественного картеля Синалоа за власть в Мексике. Насилие в регионе резко возросло, поскольку печально известный вор в законе Хоакин «Эль Чапо» Гусман был экстрадированный в США в прошлом году, оставив своих сыновей, Ивана и Альфредо вести борьбу с его бывшей «правой рукой» Дамао Лопесом за контроль над картелем.

Когда Вальдес взял интервью у посредника, присланного Лопесом в феврале 2017 года, сыновья Гусман позвонили в редакцию «Риодоче» и предупредили, чтобы не печатать статью. Они предложили скупить весь тираж, но Вальдес оставался непоколебим. Когда газету начали развозили, вооруженные бандиты картеля преследовали почтовые автофургоны по всему Кулиакану и скупили все экземпляры. Коллеги Вальдеса полагают, что именно решение о проведении интервью стоило ему жизни.

Адриан Лопес, редактор «Нороесте», еще одной газеты Синалоа, сообщил «Индексу», что смерть Вальдеса вызвала «много негодования, гнева и страха» среди местной общественности. Избрав мишенью такую известную личность, – сказал он, – убийцы передали серьезное послание мексиканским журналистам, активистам и обществу: «Если мы можем убить Хавьера, мы можем убить кого угодно».

Лопес также испытал вмешательство наркобизнеса в редакционную политику. В 2010 году бандиты произвели 64 выстрела по офисам «Нороесте» в прибрежном городе Мазатлан. Нападавшие угрожали сотрудникам газеты по телефону ранее, принуждая их приписать недавнее насилие картелю-сопернику. «Мы решили не публиковать то, что они хотели, потому что мы верим, что не можем сказать «да» этим требованиям», – рассказал Лопес. «Если вы скажете «да» один раз, то вы никогда не сможете сказать «нет» в будущем».

Лопес стал мишенью при обстоятельствах, подобно Вальдесу, в 2014 году, когда вооруженные люди задержали его машину в столице штата Кулиакан. Нападавшие украли его автомобиль, бумажник, телефон, ноутбук и прострелили ему ногу. Неделями ранее журналистов «Нороесте» запугивали и избивали во время освещения дела Гусмана и картеля Синалоа.

Лопес отметил, что его газета постоянно работает над улучшением протоколов безопасности. «Нороесте» нанимает юристов для подготовки докладов о каждой угрозе соответствующим органам власти и взяла на работу психотерапевтов для психологической поддержки персонала. «Насилие, которое мы освещаем изо дня в день, не нормально, – объяснил Лопес. «Нам нужна профессиональная помощь, чтобы осмыслить и говорить больше об этих вещах и о травме, которую может вызвать насилие».

Более 100 мексиканских журналистов были убиты с 2000 года и не менее 23 исчезли. В каждом следующем году из трех прошлых лет произошло больше убийств, чем в предыдущем, и этот год может стать наиболее смертоносным после того, как 10 журналистов были убиты в первые восемь месяцев 2017 года (по состоянию на 23 августа). Мексиканские власти часто причастны к этим нападениям. Правозащитная организация наблюдателей за соблюдением свободы прессы «Статья 19» зафиксировала 426 нападений на СМИ в прошлом году и их возрастание на 7% по сравнению с 2015 годом. Государственные чиновники и силы безопасности были признаны ответственными за 53% этих нападений.

Аналитик по вопросам безопасности Алехандро Хоуп рассказал «Индексу»: «Федеральные власти не смогли должным образом расследовать эти случаи и привлечь виновных к ответственности. Они создали среду безнаказанности, что позволило атакам на прессу процветать».

В июле 2010 года правительство учредило Прокуратуру по расследованию преступлений против свободы слова (Feadle) для расследования правонарушений против средств массовой информации. Это агентство, которое не ответило на просьбу «Индекса» о проведении интервью, предоставило журналистам, находящимся в опасности, «кнопки паники», установило камеры безопасности в их домах и в экстренных ситуациях обеспечило их телохранителями. Но на конец 2016 года из общего числа 798 расследований, Прокуратура вынесла всего три обвинительных приговора против виновных в нападениях на журналистов.

В свете обострения насилия в отношении прессы, президент Энрике Пенья Ньето назначил в мае 2017 года нового директора Feadle для активизации деятельности. В следующем месяце его правительство объявило о вознаграждении в 1,5 млн. песо (83 000 долл. США) за информацию о лицах, ответственных за убийство журналистов.

Хоуп отметил, что Мексика сделала в последнее десятилетия некоторый прогресс в отношении свободы прессы за счет развития критических, независимых новостных сайтов и улучшения доступа общественности к правительственным данным. Тем не менее, – отмечает он, – это достижения в основном на национальном уровне, в то время как журналисты в определенных регионах работают «в гораздо более сложных условиях».

Наибольшие трудности связаны с наблюдением за изменением взаимоотношений между местными властями и наркобандами, – рассказал Хоуп. Он приводит в качестве примера случай Мирославы Брич, уважаемого репортера, которая была убита в Чихуахуа в апреле 2017 года после расследования связей местных политиков с организованной преступностью.

Для оптимизма мало причин. Мексика готовится к всеобщим выборам в следующем году, но недавние избрания были омрачены обвинениями в мошенничестве и запугиваниями избирателей. Хоуп предупредил, что выборы могут нарушить существующие соглашения между преступниками и должностными лицами, сделав работу местных журналистов еще более опасной. Он считает, что нынешняя волна насилия будет продолжаться на протяжении всего избирательного цикла, «потому что на месте событий будет прибывать большее количество журналистов, подготавливая репортажи по конфликтных регионам».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

МЕКСИКАНСКИЙ УОТЕРГЕЙТ

Исследование Citizen Lab и The New York Times этим летом показало, что сообщения журналистам и другим лицам были отправлены с помощью шпионского программного обеспечения Pegasus, разработанного израильской кибер-оружейной компанией NSO Group. Некоторые издания назвали это «мексиканским Уотергейтом».

Одной из намеченных целей программы-шпиона был Рафаэль Кабрера, член группы журналистов-расследователей во главе с Кармен Аристеги, которые потеряли работу на национальной радиостанции после разоблачения коррупционного скандала с участием президента Энрике Пенья Ньето и его жены Анхелики Ривера.

«Индекс» разговаривал с ним два года назад касательно его освещения этого скандала (зима 2015 года, номер 44.04, с. 76-80). В то время Кабрера начал получать таинственные текстовые сообщения с предупреждениями о том, что ему и его коллегам может быть предъявлен иск или грозит заключение за их расследования.

В сообщениях содержались ссылки на дальнейшую информацию, но Кабрера опасался открывать их из-за возможного наличия вируса.

И он был прав. Как выяснилось, открытие такой ссылки предоставило бы отправителям доступ к данным Кабреры, к просмотру каждого нажатия клавиши его телефона и возможность скрыто использовать его камеру и микрофон.

NSO Group заявляет, что продает шпионское программное обеспечение исключительно правительствам при условии, что его будут использовать только для слежки за преступниками и террористами. Но расследование показало, что Аристеги и ее сын-подросток тоже были мишенями, наряду с другими журналистами, лидерами оппозиции, антикоррупционными активистами и защитниками общественного здравоохранения.

Пенья Ньето в ответ сказал, что против тех, кто «делает ложные обвинения в адрес правительства», будет применятся закон. Его пресс-секретарь позже сообщил в интервью The New York Times: «Никоим образом президент не пытался угрожать The New York Times или любой из этих групп. Президент оговорился».

Однако правительство признало использование шпионского программного обеспечения против преступных группировок, отрицая шпионаж за гражданскими лицами. Власти пообещали провести расследование.

Кабрера рассказал «Индексу», что он мало верит в то, что правительство будет справедливо расследовать свои собственные программы наблюдения. Он также выразил тревогу из-за первоначальной реакции Пеньи Ньето. «Это совсем неправильно, когда президент заявляет, что будет возбуждать против вас уголовные дела», – сказал Кабрера. «Он вышел за рамки интервью и позволил нам взглянуть на его внутреннего диктатора».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

ВЗЯТКА ИЛИ ПУЛЯ

Мексиканские журналисты вынуждены сталкиваться со всеми видами угроз и финансовым давлением от наркокартелей и государственных субъектов. «Статья 19» зафиксировала 426 нападений на мексиканских представителей СМИ в 2016 году, в том числе 11 убийств, 81 физическое нападение, 79 актов запугивания, 76 прямых угроз, 58 похищений и 43 акта преследования.

Картели проникли в редакции в районах, охваченных преступностью, как правило, предлагая журналистам выбор между plata o plomo, серебром или свинцом, что означает взятку или пулю. Как рассказал известный журналист Хавьер Вальдес «Индексу» за несколько месяцев до своего убийства, это создает страх и недоверие в новостных командах и поощряет самоцензуру.

Многие издания опасаются также критиковать государство, потому что они в значительной степени зависят от правительственной рекламы. В 2015 году федеральное правительство и правительства штатов потратили около 1,24 млрд. долларов на рекламу. Критики называют это формой «мягкой цензуры», поскольку издания должны работать со скрытой угрозой того, что правительство будет наказывать любое неблагоприятное освещение новостей путем снятия финансирования.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

ТЯЖЕЛЫЕ ЦИФРЫ

-

По меньшей мере 107 журналистов были убиты в Мексике с 2000 года. Из общего числа – 99 мужчин и 8 женщин.

-

С мая 2003 года по май 2017 года в Мексике исчезли 23 журналиста.

-

Государственные чиновники были замешаны в 53% всех нападений на прессу в 2016 году. В период с 2010 по 2016 год 798 атак против журналистов были расследованы со стороны властей. Только виновные в трех нападениях понесли уголовное наказание.

-

Более 200 000 человек были убиты или исчезли с тех пор, как началась Мексиканская нарковойна в декабре 2006 года.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Это исследование было проведено для «Индекса» Дунканом Такером, журналистом, пребывающем в Гвадалахаре, Мексика

Статья впервые напечатана в выпуске журнала Индекс на Цензуру (весна 2017)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to Air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

MEPs David Casa (EPP), Ana Gomes (S&D), Monica Macovei (ECR), Maite Pagazaurtundúa (ALDE) Stelios Kouloglou (GUE) and Benedek Jávor (Greens) have joined forces to push for EU legislation that will address and end “SLAPPs” – lawsuits intended to intimidate and silence investigative journalists and independent media by burdening them with exorbitant legal expenses until they abandon their opposition. According to the MEPs, the practice is abusive, poses a threat to media freedom and has no place in the European Union.

MEPs David Casa (EPP), Ana Gomes (S&D), Monica Macovei (ECR), Maite Pagazaurtundúa (ALDE) Stelios Kouloglou (GUE) and Benedek Jávor (Greens) have joined forces to push for EU legislation that will address and end “SLAPPs” – lawsuits intended to intimidate and silence investigative journalists and independent media by burdening them with exorbitant legal expenses until they abandon their opposition. According to the MEPs, the practice is abusive, poses a threat to media freedom and has no place in the European Union.