16 May 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

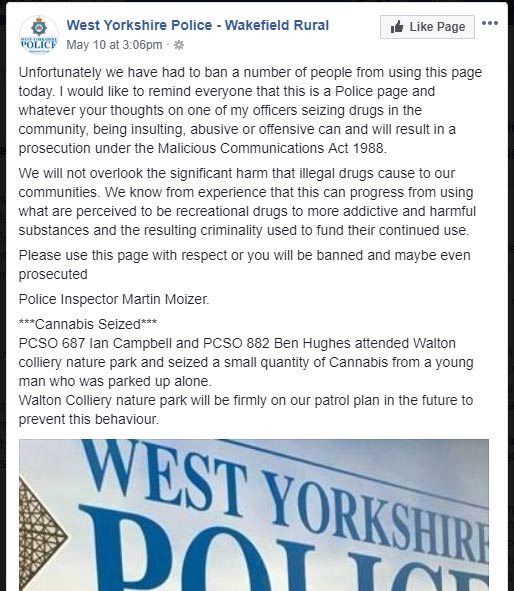

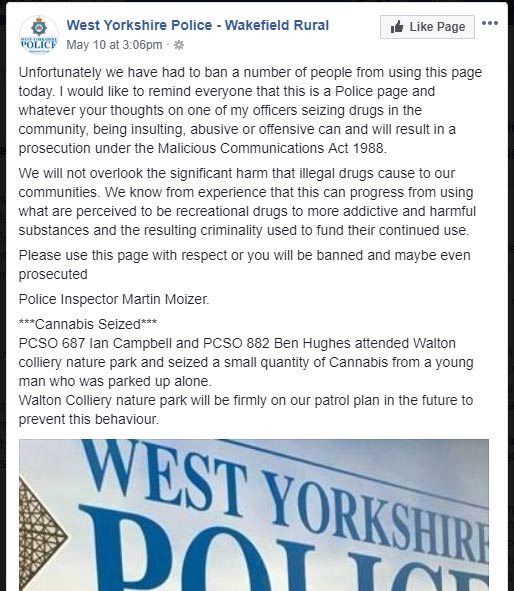

The West Yorkshire Police force do not know their law.

Malicious Communications Act 1988 has no provision whatsoever for “insulting or abusive” messages.

Individuals can be prosecuted for sending messages that are “grossly offensive” or for messages that the sender knows to be false but sends anyway for the purpose of causing annoyance.

“This police force needs to develop a sense of humour and pursue actual crime rather than trying to use the law to cover their own embarrassment. These comments by the West Yorkshire Police again show how problematic this section of law is in dealing with social media and it is time to see the ‘grossly offensive’ element scrapped,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said.

16 May 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, Russia, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]We, the undersigned 53 international and Russian human rights, media and Internet freedom organisations, strongly condemn the attempts by the Russian Federation to block the internet messaging service Telegram, which have resulted in extensive violations of freedom of expression and access to information, including mass collateral website blocking.

We call on Russia to stop blocking Telegram and cease its relentless attacks on internet freedom more broadly. We also call the United Nations (UN), the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the European Union (EU), the United States and other concerned governments to challenge Russia’s actions and uphold the fundamental rights to freedom of expression and privacy online as well as offline. Lastly, we call on internet companies to resist unfounded and extra-legal orders that violate their users’ rights.

Massive internet disruptions

On 13 April 2018, Moscow’s Tagansky District Court granted Roskomnadzor, Russia’s communications regulator, its request to block access to Telegram on the grounds that the company had not complied with a 2017 order to provide decryption keys to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). Since then, the actions taken by the Russian authorities to restrict access to Telegram have caused mass internet disruption, including:

- Between 16-18 April 2018, almost 20 million internet Protocol (IP) addresses were ordered to be blocked by Roskomnadzor as it attempted to restrict access to Telegram. The majority of the blocked addresses are owned by international internet companies, including Google, Amazon and Microsoft. On 30 April, the number of blocked IP addresses was 14.6 million. As of 16 May 2018, this figure is currently 10.9 million.

- This mass blocking of IP addresses has had a detrimental effect on a wide range of web-based services that have nothing to do with Telegram, including, but not limited to, online banking and booking sites, shopping, and flight reservations.

- Within a week, Agora, the human rights and legal group, representing Telegram in Russia, reported it received requests for assistance with issues arising from the mass blocking from about 60 companies and website owners, including online stores, delivery services, and software developers. The number of requests has now reached 100.

- At least six online media outlets (Petersburg Diary, Coda Story, FlashNord, FlashSiberia, Tayga.info, and 7×7) found access to their websites was temporarily blocked.

- On 17 April 2018, Roskomnadzor requested that Google and Apple remove access to the Telegram app from their App stores, despite having no basis in Russian law to make this request. At the time of publication, the app remains available, but Telegram has not been able to provide upgrades that would allow better proxy access for users.

- Virtual Private Network (VPN) providers – such as TgVPN, Le VPN and VeeSecurity proxy – have also been targeted for providing alternative means to access Telegram. Federal Law 276-FZ bans VPNs and internet anonymisers from providing access to websites banned in Russia and authorises Roskomnadzor to order the blocking of any site explaining how to use these services.

- On 3 May 2018, Rozkomnadzor stated that it had blocked access to around 50 VPN services and anonymisers in relation to the Telegram block. On the same day, the Russia’s Communications Minister refused to rule out that other messaging services, including Viber, could potentially be blocked in Russia if they do not hand over encryption keys upon request. The minister had previously warned, during an interview on 6 April 2018, that action could be taken against Viber, as well as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-file-excel-o” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Background on restrictive internet laws

Over the past six years, Russia has adopted a huge raft of laws restricting freedom of expression and the right to privacy online. These include the creation in 2012 of a blacklist of internet websites, managed by Roskomnadzor, and the incremental extension of the grounds upon which websites can be blocked, including without a court order.

The 2016 so-called ‘Yarovaya Law’, justified on the grounds of “countering extremism”, requires all communications providers and internet operators to store metadata about their users’ communications activities, to disclose decryption keys at the security services’ request, and to use only encryption methods approved by the Russian government – in practical terms, to create a backdoor for Russia’s security agents to access internet users’ data, traffic, and communications.

In October 2017, a magistrate found Telegram guilty of an administrative offense for failing to provide decryption keys to the Russian authorities – which the company states it cannot do due to Telegram’s use of end-to-end encryption. The company was fined 800,000 rubles (approx. 11,000 EUR). Telegram lost an appeal against the administrative charge in March 2018, giving the Russian authorities formal grounds to block Telegram in Russia, under Article 15.4 of the Federal Law “On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection”.

The Russian authorities’ latest move against Telegram demonstrates the serious implications for people’s freedom of expression and right to privacy online in Russia and worldwide:

- For Russian users apps such as Telegram and similar services that seek to provide secure communications are crucial for users’ safety. They provide an important source of information on critical issues of politics, economics and social life, free of undue government interference. For media outlets and journalists based in and outside Russia, Telegram serves not only as a messaging platform for secure communication with sources, but also as a publishing venue. Through its channels, Telegram acts as a carrier and distributor of content for entire media outlets as well as for individual journalists and bloggers. In light of direct and indirect state control over many traditional Russian media and the self-censorship many other media outlets feel compelled to exercise, instant messaging channels like Telegram have become a crucial means of disseminating ideas and opinions.

- Companies that comply with the requirements of the ‘Yarovaya Law’ by allowing the government a back-door key to their services jeopardise the security of the online communications of their Russian users and the people they communicate with abroad. Journalists, in particular, fear that providing the FSB with access to their communications would jeopardise their sources, a cornerstone of press freedom. Company compliance would also signal that communication services providers are willing to compromise their encryption standards and put the privacy and security of all their users at risk, as a cost of doing business.

- Beginning in July 2018, other articles of the ‘Yarovaya Law’ will come into force requiring companies to store the content of all communications for six months and to make them accessible to the security services without a court order. This would affect the communications of both people in Russia and abroad.

Such attempts by the Russian authorities to control online communications and invade privacy go far beyond what can be considered necessary and proportionate to countering terrorism and violate international law.

International Standards

- Blocking websites or apps is an extreme measure, analogous to banning a newspaper or revoking the license of a TV station. As such, it is highly likely to constitute a disproportionate interference with freedom of expression and media freedom in the vast majority of cases, and must be subject to strict scrutiny. At a minimum, any blocking measures should be clearly laid down by law and require the courts to examine whether the wholesale blocking of access to an online service is necessary and in line with the criteria established and applied by the European Court of Human Rights. Blocking Telegram and the accompanying actions clearly do not meet this standard.

- Various requirements of the ‘Yarovaya Law’ are plainly incompatible with international standards on encryption and anonymity as set out in the 2015 report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression report (A/HRC/29/32). The UN Special Rapporteur himself has written to the Russian government raising serious concerns that the ‘Yarovaya Law’ unduly restricts the rights to freedom of expression and privacy online. In the European Union, the Court of Justice has ruled that similar data retention obligations were incompatible with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Although the European Court of Human Rights has not yet ruled on the compatibility of the Russian provisions for the disclosure of decryption keys with the European Convention on Human Rights, it has found that Russia’s legal framework governing interception of communications does not provide adequate and effective guarantees against the arbitrariness and the risk of abuse inherent in any system of secret surveillance.

We, the undersigned organisations, call on:

- The Russian authorities to guarantee internet users’ right to publish and browse anonymously and ensure that any restrictions to online anonymity are subject to requirements of a court order, and comply fully with Articles 17 and 19(3) of the ICCPR, and articles 8 and 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, by:

-

-

- Desisting from blocking Telegram and refraining from requiring messaging services, such as Telegram, to provide decryption keys in order to access users private communications;

- Repealing provisions in the ‘Yarovaya Law’ requiring internet service providers (ISPs) to store all telecommunications data for six months and imposing mandatory cryptographic backdoors, and the 2014 Data Localisation law, which grant security service easy access to users’ data without sufficient safeguards.

- Repealing Federal Law 241-FZ, which bans anonymity for users of online messaging applications; and Law 276-FZ which prohibits VPNs and internet anonymisers from providing access to websites banned in Russia

-

- Amending Federal Law 149-FZ “On Information, IT Technologies and Protection of Information” so that the process of blocking websites meets international standards. Any decision to block access to a website or app should be undertaken by an independent court and be limited by requirements of necessity and proportionality for a legitimate aim. In considering whether to grant a blocking order, the court or other independent body authorised to issue such an order should consider its impact on lawful content and what technology may be used to prevent over-blocking.

- Representatives of the United Nations (UN), the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organisation for the Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE), the European Union (EU) the United States and other concerned governments to scrutinise and publicly challenge Russia’s actions in order to uphold the fundamental rights to freedom of expression and privacy both online and-offline, as stipulated in binding international agreements to which Russia is a party.

- Internet companies to resist orders that violate international human rights law. Companies should follow the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights, which emphasise that the responsibility to respect human rights applies throughout a company’s global operations regardless of where its users are located and exists independently of whether the State meets its own human rights obligations.

Signed by

- Asociatia pentru Tehnologie si Internet – ApTI

- Associação D3 – Defesa dos Direitos Digitais

- Centre for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights

- Committee to Protect Journalists

- Electronic Frontier Foundation

- Electronic Frontier Norway

- Electronic Privacy Information Centre (EPIC)

- European Federation of Journalists

- Glasnost Defence Foundation

- Human Rights House Foundation

- The Independent Historical Society

- International Media Support

- International Partnership for Human Rights

- Internet Society Bulgaria

- International Youth Human Rights Movement (YHRM)

- Interregional Human Rights Group

- Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group

- Mass Media Defence Centre

- Memorial Human Rights Center

- Movement ‘For Human Rights’

- Norwegian Helsinki Committee

- Press Development Institute-Siberia

- Reporters without Borders

- Russian Journalists’ and Media Workers’ Union

- Transparency International

- Transparency International Russia

- Webpublishers Association (Russia)

- World Wide Web Foundation

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526459542623-9472d6b1-41e3-0″ taxonomies=”15″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 May 18 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100382″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Seda Taşkın had just been sent to Muş, a tiny eastern Turkish city on a fertile plain surrounded by high mountains, to report on a few stories when police started to track her down. Hot on the case, police apparently availed themselves of a time machine, arresting the Mezopotamya news agency reporter late in December half an hour before a prosecutor had even issued an arrest warrant in concert with an informant’s tipoff. Taşkın’s subsequent trial, however, suggests that rather than breaking new grounds in physics, Turkey’s authorities are probably just breaking the law.

Taşkın appeared in court for the first time on 30 April to face charges of “membership in a terrorist organisation” and “conducting propaganda for a terrorist organisation.” The court date, however, exposed serious irregularities regarding her arrest, the treatment she received in custody and the evidence against her. During the hearing at the 2nd High Criminal Court of Muş, Taşkın’s lawyer highlighted the email address used to tip off authorities to the journalist’s alleged crimes.

According to the official document in the case file seen by Mapping Media Freedom’s Turkey correspondent, the email address denouncing Taşkın as a “militant” bore an “egm” extension, signifying the Turkish abbreviation for “general department of police.” Gulan Çağın Kaleli told the court that a mere 20 minutes were required to locate Taşkın and arrest her – a period that’s even less than the time it took to issue a mandatory arrest warrant. Questioning whether the anti-terror unit had, in fact, fabricated the tipoff, Kaleli requested that the source of the email be identified according to its IP number, but the court ultimately rejected the demand.

“The police tipped her off and the state caught her. This was the mise-en-scène,” said Hakkı Boltan, the co-president of the Free Journalists’ Initiative (ÖGİ), a Diyarbakır-based journalistic group that monitors press freedom violations and aids journalists who face legal proceedings in Kurdish provinces.

Taşkın is a journalist based in the city of Van who mainly covers social and cultural news. At the time of her arrest, she was working on several reports, including a story about the family of Sisê Bingöl. Authorities jailed the 78-year-old woman in June 2016 in Muş’s Varto district on accusations of being a “terrorist” before sentencing her to four years and two months in prison. Boltan told MMF that this type of reporting is often considered as threatening to the state as it reveals police violations. “The public has the right to be informed about this unjust imprisonment. This is what Seda was trying to do when she was targeted by the state.”

Ill treatment from police, threats from the prosecutor

Turkish authorities arrested Taşkın on 20 December 2017 before freeing her four days later. The prosecutor, however, filed an objection against the court’s release order. A month later, on 23 January, officers again arrested Taşkın in Ankara, where the journalist had gone to join her family.

In her defense, Taşkın told the court that police subjected her to a strip search after her initial arrest. “When I refused, they said they would force me,” she said via a judicial video conferencing system from Ankara’s Sincan Women Prison Facility, where she remains in custody pending trial. She was subjected to a second strip search before finally seeing her lawyer. “I was also physically beaten when I refused to get in the armoured vehicle. If I’m telling this, it’s because I want the court to take it into consideration,” she said.

The court didn’t appear greatly concerned.

Taşkın was also threatened after her initial release from custody. “The prosecutor told her ‘How can you be freed? You will see, we will file an objection’ in front of her lawyer as a witness,” Kaleli told the court.

The lawyer also said the evidence against her client was restricted to retweets and Facebook shares – mostly of news articles. There is not even a single article written by Taşkın in the case file, she said. “You may not like the agency where my client works. But this agency is still operating legally, and this is about freedom of expression and press freedom.”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”100383″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]Touring villages with her camera

Included in the indictment as evidence was a “package” that a colleague sought to give Taşkın. There was a certain air of mystery to the private Instagram conversation between Taşkın and her colleague, Diyarbakır-based journalist and photographer Refik Tekin, but the item in question was only a fleece – and police could have ascertained the innocence of the matter had they clicked on the embedded link in the conversation.

Tekin told MMF that the pair had merely discussed the logistics of Taşkın receiving the fleece in Muş. He eventually sent the item of clothing to the prison in Ankara after she was jailed, but Taşkın was still unable to obtain it: The fleece is dark blue – a color that is banned in prison because it matches the uniforms of guards.

Tekin said Taşkın loves photography. She would tour villages around Lake Van in search of news and human stories. “She is a very friendly person. People in villages are usually somewhat shy, but they would immediately open up to Seda,” Tekin said. “She took photos of children in villages, women working in fields… Those were beautiful, very touching. They would tell a story. She would be on the top of the world when her photos appeared in [the now-closed newspaper] Özgürlükçü Demokrasi,” he said.

Her close friend Nimet Ölmez, also a Van-based reporter for Mezopotamya, said Taşkın’s picture of two children returning from school with their dirty clothes and large baskets instead of backpacks helped raise awareness about the precarious situation of children living in the impoverished villages of the region. “They were shared on social media for days. So many people called and asked us how they could help.”

But she admits that Taşkın’s love for photography was perhaps a bit on the excessive side. “She would take so many photos that all our memory sticks would fill up. She once went to a village to report on some shepherd. He had around 200 sheep, but Seda still managed to come back with 230 photos – more than one photo per sheep,” she joked. “I really miss fighting for photos, memory sticks and news with her.”

On 30 April, the court ruled against Taşkın’s release on the grounds that she doesn’t use the name on her ID card, Seher, in daily life, even though everyone, including her close family, calls her Seda.

The next hearing will be held on 2 July in Muş – a town that appears in a popular song with the lyrics “the road to Muş is uphill.” Rather than just Muş, it seems the song’s writers were talking about the road to justice in Turkey today.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-file-excel-o” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Media freedom violations reported to MMF since 24 May 2014

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526396916736-92769289-9c57-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 May 18 | Index in the Press

Police stored innocent people’s biometrics data after mistaking them for criminals, says privacy group. The Metropolitan Police’s use of facial recognition is misidentifying innocent people as wanted criminals more than nine times out of 10, according to a privacy campaign group. Read in full.

15 May 18 | Index in the Press

Protests have been taking place outside Downing Street ahead of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s meeting with Prime Minister Theresa May. Mr Erdogan, who arrived in Britain on Sunday for a three-day visit, will also meet the Queen. Read the full article.

15 May 18 | Index in the Press

Protesters have been demonstrating ahead of Mr Erdogan’s talks with Prime Minister Theresa May on Tuesday afternoon. Critics accused the PM of “cosying up” to the totalitarian leader for economic reasons as she prepared to host him in No 10. Read in full.

15 May 18 | Academic Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100370″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Written by: Che Applewhaite, Samantha Chambers, Claire Kopsky and Sarah Wu

Survivors of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, have been making headlines lately with their calls for more American students to help them change the country’s gun laws. Their right to protest and petition politicians is enshrined in their right to free expression under the First Amendment.

It is clear that the US student body — whether at high school or college — is conflicted over the issue of free expression and what is or isn’t acceptable speech. While some recent surveys and studies show attitudes to be generally supportive of freedom of expression as an important right, in practice this isn’t always the case.

At this vital moment, students around the USA should see why free speech is so vital on their campuses, whether high school or university and what they have to lose if they won’t fight for it.

“Free speech must apply to everyone — even those whose views we find objectionable — or it applies to no one,” says Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship. “Only by being able to express themselves freely and honestly, and also being exposed to as wide a range of viewpoints as possible can these get the most out of their education.”

In the past, the usefulness of free speech as part of such a campaign was much less in dispute. Martin Luther King Jr’s speeches and the student movements of the 1960s, which together changed a generation, relied on this very freedom. A lot of demonstrations today seem more geared towards the suppression of speech, such as those targeting conservative and alt-right voices like Milo Yiannopoulos at Berkeley and Richard Spencer at Michigan State University.

Students from four US universities weigh in on the issue and tell Index what is fair game on campus and what isn’t.

(Not) talking about race

The University of Missouri, colloquially known as a Mizzou and described as a “liberal student body in a red state”, is no stranger to racial tension. In 2015 the school saw protests by its football team and a graduate student go on hunger strike as part of a campaign to have the school’s president resign after mishandling racial issues on campus. This was followed by a drop in freshman enrollment and funding to the school.

Evan Lachnit, who studies journalism and sports at Mizzou, says that there are certain topics that, in the current political climate, are often too hot to touch. “As it relates to history, if there is one subject everyone appears to walk-on eggshells around, it would be slavery, one of, if not the largest, scars in American history,” he says. “It’s something many will just avoid altogether.”

The issue of “hate speech” — including speech considered to be insulting to a particular race — at Mizzou prompted the University of Missouri Police Department issued a campus-wide email asking “individuals who witness incidents of hateful and/or hurtful speech” to call them “immediately”. The police admit that “cases of hateful and hurtful speech are not crimes”, leaving many to wonder why they feel this is an issue the force should be concerned with.

“There is no question that a great deal of ‘hateful and/or hurtful speech’ is protected by the First Amendment, and that punishing students whose speech is determined to meet such a troublingly vague and subjective standard will violate students’ constitutional rights,” Fire, an organisation that campaigns for individual rights in higher education, said in a letter to the school’s chancellor, R. Bowen Loftin. “It is crucial that students be able to carry out such debates without fear that giving offence will result in being reported to the police and referred for discipline by the university.”

Sophie Kissinger, a senior studying history at Harvard University, claims that the ways in which her subject was taught in the past limits knowledge of American slavery today. Recently gifted a 1926 Harvard syllabus that outlines the core requirements for a history student at the time, she notices the document’s “neglect of the oppressed”. “These narratives largely serve to perpetuate a system of erasure, reinforcing colonial ideologies and degrading the lives of oppressed peoples,” she says. “This erasure is all around us today: only 8% of high school senior can identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War and most don’t know an amendment to the US Constitution formally ended slavery”.

Over at Villanova University, Emily Bouley, a junior studying business and psychology, says that privilege can be tricky to discuss because “everyone has different definitions of what privileged means”.

One topic in particular that’s likely to receive backlash, Bouley says, is affirmative action, those measures that are intended to end and correct the effects of a specific form of discrimination. “One time my professor was really passionate about racism against white males in job selection since there are more programs aimed towards diversity now than ever before, which is great, but sometimes candidates will get chosen because they are of a minority,” Bouley says. “Often this isn’t the case, but I felt so uncomfortable sharing my opinion because yes it happens and doesn’t support equality but it’s very hard to argue without sounding racist.”

Thanksgiving rule on campus: no politics

Located in the fifth most liberal city in America as ranked by Forbes, Boston University students are aware of the politically left-leaning environment they live in. But as with the family dinner table at Thanksgiving, heated conversation about politics is discouraged on campus.

According to the school’s policies, students must not “impose” offensive or upsetting views on others. Nicole Hoey, a junior studying journalism and English at the school, says the overwhelming liberal majority, though welcoming of opposing ideas, has a tendency to silence conservative voices through the sheer volume of liberal students. “As a journalist, free speech is so important,” Hoey says. “And for the most part, BU does a good job at promoting free speech on campus.”

“But I think people who voted for Trump would feel more frightened to speak their minds because we’re so liberal,” Hoey adds. “I think the only time they would feel safe is if they’re in College Republicans”.

This is probably why, following the 2016 election and the election of Donald Trump as president, BU College Republicans have seen an increase in attendance.

International studies major at the University of San Francisco Adule Dajani notes that “professors make their political views known pretty discreetly”. As a left-leaning school in a democratic state, Dajani says that USF professors try to remain unbiased by “talking about both the pros and cons of an issue”. However, she finds the conduct of the classroom facilitated by professors to be the main silencer for those in the minority side on any debate. “I can see how someone would feel too uncomfortable to speak up because the students are hotheads,” she says.

Candace Korasick, a professor at the school’s department of sociology at Mizzou, says her classes often tackle difficult issues, but there are some too controversial to discuss. “There are topics that I once would have broached in a class that I, not avoid, but now don’t initiate. And if students initiate them, I feel as if I’m tiptoeing through a minefield,” Korasick explains. “The two topics that I’d rather avoid are abortion and the Confederate flag. It is difficult to have a conversation with more than one or two students at a time on issues like that.”

Journalism and business student Nina Ruhe says topics like race, sexual assault and political beliefs are ones professors handle with “delicacy” on a surface level. For her, that’s a shame because it means she’s not getting any depth of knowledge on these topics as part of her education.

“While doing this allows the educators to say they’ve covered the issues and say that they’ve taken part in these important discussions, they also don’t go deep enough as to letting there be any real form of discussion,” Ruhe says. “Unfortunately, when I have heard of educators that have attempted to go into in-depth conversations about these topics, they are shut down by complaints from parents or superiors and are forced to stop.”

The right to freedom of expression and the right to peaceful protest are crucial in a democracy – and crucial to any success the students of Parkland may have in changing America’s gun laws. They must be in no doubt that it a right that is on their side.

Later this year Index on Censorship will release a report on the freedom of speech on campus[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526388582695-a56b5824-ce86-7″ taxonomies=”8843″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 May 18 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Turkey, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley leads chants in support of Turkey’s jailed journalists ahead of Erdogan visit to Downing Street

Hundreds of demonstrators gathered outside Downing Street today ahead of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s meeting with UK prime minister Theresa May.

Index joined English Pen, Reporters Without Borders, Cartoonist Rights Network International and dozens of protesters to call on the British government to hold president Erdogan accountable for the ongoing crackdown on journalists and free speech within Turkey following the attempted coup in July 2016. Other groups, including the Kurdish Solidarity Campaign, also demonstrated against Erdogan’s visit in large numbers.

Addressing the crowd, Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley said: “If Theresa May cares about free speech, if this government cares about free speech and free expression, this should be on the table for this meeting with President Erdogan. “This British government often talks about its commitment to free speech, so let’s see the sign of this in its international politics. How can we believe in a government’s commitment to free expression if it is willing to meet international leaders where free expression is massively threatened and they do not talk about that.”

Under the state of emergency declared since the intended coup in 2016, voices critical of the Turkish government have seen a major crackdown.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 May 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The killings of at least 40 unarmed Palestinian protesters by Israel Defense Forces marks a grave and horrendous assault on the right to protest. Reports say more than 1,700 people, including journalists, have been injured.

Index on Censorship demands the Israeli government halt its aggression toward the Great March of Return protesters and immediately take steps to deescalate the situation.

“We call on the Israeli authorities to commit to upholding the international agreements they are party to — specifically the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights — that uphold the rights to freedom of expression, assembly and the right to life. This is a dark day for the state of Israel and its standing in the world,” Rachael Jolley, Editor, Index on Censorship said.

Monday’s killings follow months of protests that began in March by Palestinians to highlight the loss of homes in the wake of founding of the state of Israel. In addition to the killing of at 40 protesters, photojournalists Yaser Murtaja and Ahmad Abu Hussein were killed covering the demonstrations before the 14 May bloodshed.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526305100409-f494ed6d-a2d0-1″ taxonomies=”6534″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 May 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Press Releases

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Freedom of expression organisation Index on Censorship calls on Egypt to immediately release activist Amal Fathy, who was detained by police last Friday.

Fathy was arrested alongside her husband Mohamed Lotfy, director of the award-winning human rights organisation, the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms. Police raided the couple’s home in Cairo at 2.30 a.m. and took them and their 3-year-old child to the police station. Security officers searched their house, their mobile phones were seized and they were denied the right to communicate with a lawyer or family.

Lotfy and their child were released after three hours but Fathy has been ordered to remain in detention for 15 days on “on charges of incitement to overthrow the ruling system, publishing lies and misusing social media”.

On Wednesday, Fathy posted a video on her Facebook page in which she spoke about the prevalence of sexual harassment in Egypt, criticizing the government’s failure to protect women. She also criticised the government for deteriorating human rights, socioeconomic conditions and public services.

Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship, said: “This is just the latest attempt by the Egyptian government to stop the public being informed about what is going in their country. The authorities must release Amal Fathy immediately.”

Fathy’s husband is co-founder of the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF). ECRF, a 2018 winner of an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression award, works on documenting cases concerning torture in prisons and enforced disappearance in an increasingly difficult climate in Egypt where independent voices are suppressed and threatened.

For more information, please contact Jodie Ginsberg at jodie@indexoncensorship.org[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526299869862-1ce8ff4a-0268-2″ taxonomies=”147, 24135″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 May 18 | Artistic Freedom, Media Freedom, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100332″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]All that is solid in the Turkish media melted into air over the past year, and much of the entertainment content has migrated from traditional platforms to streaming services like YouTube and Netflix.

Turkey’s watchdogs took notice. In March parliament passed a law that expands the powers of Turkey’s Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK), including blocking internet broadcasts. With the new law the state hopes to have some degree of control over online content that it considers dangerous.

This spring, many bulwarks of Turkish media have shape-shifted. In April, Turkey’s biggest media conglomerate, Doğan, changed hands. Foreign media titles with Turkish editions, including the Wall Street Journal, Newsweek and Al Jazeera, have already pulled out of the Turkish market. Newspaper circulations saw sharp decline.

Meanwhile online streaming services have thrived. Spotify entered Turkey in 2013 and pushed its premium service with a Vodafone deal two years later. On Twitter, BBC’s Turkish service has just short of three million followers. Netflix introduced its Turkish service in 2016. Last year it too signed a deal with Vodafone, and Netflix Turkey pushed its products aggressively, with posters of House of Cards plastered in Istanbul’s subway stations.

Statista, an online statistics website, predicts there will be approximately 397.4 thousand active streaming subscribers to Netflix in Turkey in 2019.

Turkish-owned streaming services also came to the fore. In 2012 Doğuş Media Group launched its video on demand service, puhutv, and there was excitement last year when the channel showed its first series, Fi, based on a best-selling trilogy by Turkish author Azra Kohen. The series quickly became a sensation, largely thanks to scenes featuring nudity and racy sexual encounters.

Puhutv is a free, ad-supported service and watching Fi on Puhutv meant seeing many ads of condoms, dark chocolates and other products linked with pleasure. In just three days, the pilot episode of Fi was viewed more than four and a half million times.

For content producers the Turkish love for the internet means new opportunities for profit. In February a report by Interpress found that the number of internet users increased by 13 percent to 51 million from the past year. Turkey is one of the largest markets for social media networks and it ranks among the top five countries with largest Facebook country populations.

The RTÜK watchdog, which now has great control over streaming services, normally chases television broadcasters. It famously went after popular TV dating shows last year, and producers faced heavy fines accused of violating ‘public morals’. Marriage with Zuhal Topal, Esra Erol and other shows were pulled off the air. A famous dating show duo, Seda Sayan and Uğur Arslan, considered releasing their show Come Here if You’ll Get Married on the internet.

Those dating shows outraged not only conservatives but many other swaths of Turkish society. Feminists considered them an affront to women’s struggle and they signed a petition to ban dating shows en masse. RTUK announced there were around 120 thousand complaints from viewers about the shows.

With the new bill, producers of shows streamed online will need to obtain licenses. “The broadcasts will be supervised the same way RTÜK supervises landline, satellite and cable broadcasts,” reads the new law which gives RTÜK the power to ban shows that don’t get the approval of Turkish Intelligence Agency and the General Directorate of Security.

Family Ties, a recent episode of the US series Designated Survivor angered many viewers when it was broadcast last November. One of the characters in the episode was a thinly veiled representation of Fethullah Gülen, an imam who leads a global Islamist network named Hizmet (‘The Service’).

The Turkish state accuses Hizmet, its US-based leaders and followers in the Turkish Army of masterminding 2016’s failed coup attempt, during which 250 people were killed. Turkey has requested Gülen’s extradition.

But in Family Ties, the Gülen-like character was described as an “activist”, and this led to protests on Twitter in Turkey. Some Turks wanted the show banned. In Turkey Designated Survivor is streamed by Netflix.

In September Netflix will release The Protector, its first Turkish television series by up and coming film director Can Evrenol. “The series follows the epic adventure of Hakan, a young shopkeeper whose modern world gets turned upside down when he learns he’s connected to a secret, ancient order, tasked with protecting Istanbul,” according to a Netflix press release.

“Streaming services give freedom and enthusiasm to directors who are normally reluctant to work for television,” Selin Gürel, a film critic for Milliyet Sanat magazine said.

“Content regulations are unwelcome, but I don’t think anyone would give up telling stories because of them. Directors like Can Evrenol are capable of finding some other way for protecting their style and vision.”

In Gürel’s view, the new regulations will not lead to dramatic changes for Turkish films.

“It is annoying that RTÜK now spreads its control to interactive platforms like Netflix,” said Kerem Akça, a film critic for Posta newspaper. “RTÜK should keep its hands away from paid platforms.”

Akça has high expectations from Evrenol’s new film, but he fears the effects of new regulations on The Protector and future Turkish shows for Netflix can be harmful.

“The real problem is whether RTÜK’s control on content shape-shifts into self-censorship,” Akça said. “Before it does, someone needs to take the necessary steps to avoid content censorship on Netflix.”

But Turkish artists have long found ways of avoiding the censors, and new regulations can even lead to more original thinking.

“This is a new zone for RTÜK,” Gürel, the critic, said. “I am sure that vagueness will be useful for creators, at least for a while.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Press freedom violations in Turkey reported to Mapping Media Freedom since 24 May 2014

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526292811243-b24bb16c-ba6d-1″ taxonomies=”7355″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 May 18 | Czech Republic, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

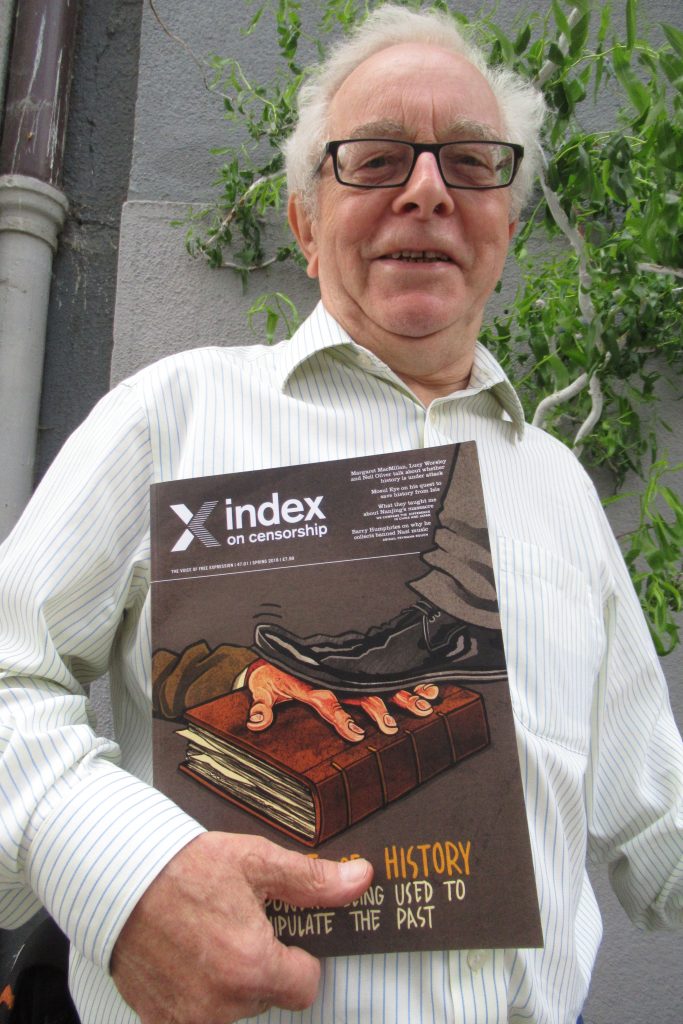

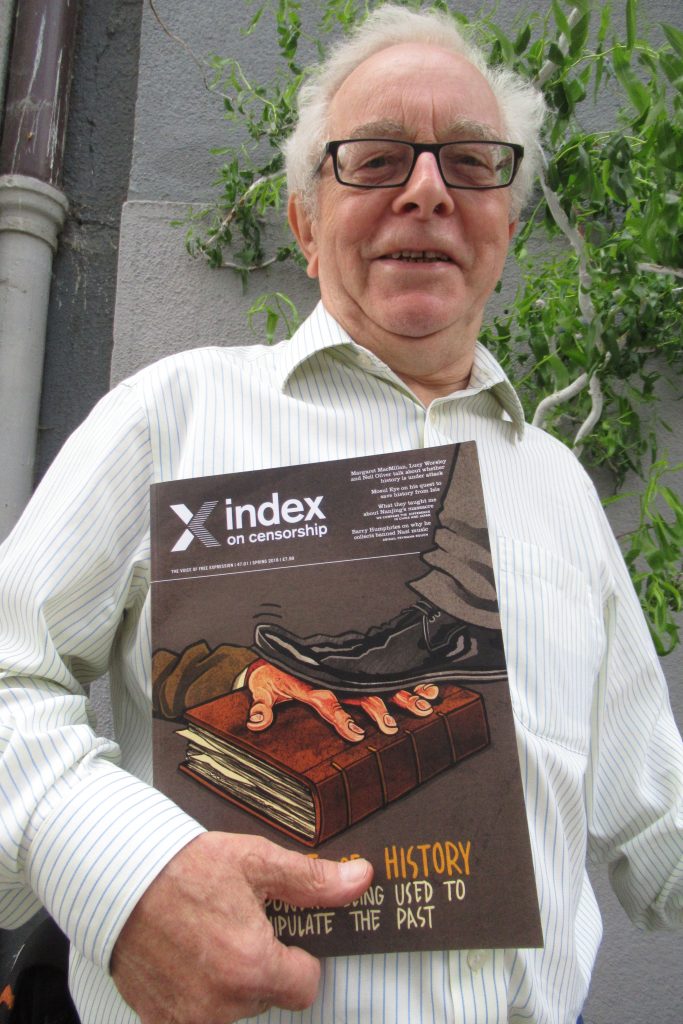

2018 winner of the George Theiner Award David Short with a copy of Index on Censorship magazine

British academic David Short has been announced as the recipient of the George Theiner Award 2018.

Named in honour of George, also known as Jiri, Theiner, the former editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine, the literary award is given to people and organisations outside the Czech Republic, who have made long-term contributions to the promotion of Czech literature and free expression across the globe.

George Theiner was widely respected by writers and poets in Czechoslovakia and across the globe for his work translating Czech works into English, including Vaclav Havel, Ivan Klima,

and Ludvik Vaculik. Theiner was the deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine throughout the 1970s, and, following Michael Scammell’s departure, as the editor in the 1980s.

First awarded in 2011 and created by World of Books, the award is presented at the Prague book fair in May each year. The winner is decided by a five-person jury, and also receives a prize of £1000.

This year’s winner Short is a British academic who taught Czech and Slovak at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London, from 1973 to 2011. Over the years he has translated various Czech works into English, including a number of Slovak authors and also created a well-respected Czech-English/English-Czech dictionary, all of which contributed to the profile of Czech authors and literature abroad.

Pavel Theiner, son of George, said: “As always, the recipient has in a major way, and over a long period, contributed to the promotion of Czech literature abroad. David Short is remarkably modest, multilingual, an expert in terms of the grammar and his Czech-English/English-Czech dictionary is extremely well respected.”

Previous winners include Ruth Bondy, who won the award in 2012. Bondy was an Auschwitz and Theresienstadt survivor who moved to Israel after the war to work as a journalist for Hebrew daily newspaper Davar. She taught journalism at the Tel Aviv University in the 1980s and 1990s, as well as translating a number of Czech authors into Hebrew, including the first translation into Hebrew of Hasek´s Good Soldier Schweik. Bondy sadly passed away in November 2017 aged 94.