01 May 18 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Russia, Ukraine

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100124″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Flying from Moscow to Simferopol is quick and relatively affordable if you’re travelling out of season, but according to Ukrainian law it’s also illegal. After the 2014 Russian annexation of the peninsula, Ukraine passed a law that prohibits travelling to Crimea via Russia. Violating it can lead to a fine and a ban on entering Ukraine.

Journalists who travel to Crimea via Ukraine need the necessary documentation to work in a territory that is de facto controlled by Russia. In addition to a Russian accreditation and work visas — obtained at the end of a long and demanding process that can prove particularly difficult for freelancers — journalists also need to make their way to Kyiv and present a series of documents to Ukraine’s ministry of information and immigration service, to obtain a permit to enter Crimea, which takes a minimum of one or two days. Then they can head south and make their way to what has become the border with Crimea, 668 kilometres away. Once on the peninsula, they are usually interviewed by FSB officers.

Anton Naumliuk, a Russian journalist who covers Crimea for Radio Liberty, has been travelling to the peninsula about six times a year recently, always via Ukraine. He says he’s noticed that the procedure on the Ukrainian side is becoming simpler and faster. He’s also seen the border gradually built up. “Two years ago there was nothing, just the ground,” he said. Now there’s portacabins and fences. In the summer, there can be long queues.

Journalists often encounter difficulties on the Russian side, he explained. “[FSB officers] ask you who you’ll meet. This interrogation can take hours. If the journalist is quite well-known they try not to do it. If you’re young, if you’re Ukrainian, or carry equipment, you’re more likely to be interrogated. It can be quite nerve-wracking.”

Journalists can be asked to display the content of their phones or computers, although, according to Russian law, they cannot be forced to provide passwords to law enforcement. Officers can search hard drives or flashcards. This means journalists are advised to wipe any sensitive information which could compromise their sources before crossing the border. FSB agents have also been known to ask journalists for their phones’ IMEI number, which could allow them to track the person’s movements when they are reporting in the peninsula.

On my way back from a recent reporting trip to Crimea I met Tetiana Pechonchyk, who monitors human rights violations in Crimea at the Human Rights Information Centre in Kyiv. Her organisation has been campaigning for an easier access for journalists to the peninsula, in a context where coverage by Ukrainian journalists has gradually become near to impossible. “Almost no Ukrainian journalist is able to work in Crimea. A lot of Ukrainian journalists who covered the occupation and persecutions connected to it left Crimea. Ten Crimean media outlets moved to mainland Ukraine with their staff. They continue to cover Crimea but a majority of the websites are blocked on the peninsula, while not being blocked in Russia,” she said.

According to the Human Rights Information Centre’s monitoring, the number of assaults against journalists in Crimea has gone down, but for Pechonchyk, this does not mean much: “They pushed most of independent journalists out. Once you’ve emptied the field then you have no one to repress. They were lots of physical attacks in 2014. In 2015 Russia used legal tools against media outlets. They wouldn’t give a Russian license to outlets. Then they picked journalists who work for the Ukrainian media and terrified them one by one. Small media and bloggers have started appearing in Crimea. The role of professional journalists has been taken over by average citizens who film videos of searches in Tatar houses, go to politically motivated trials to cover them. Now authorities have started persecuting citizen journalists as well.”

Naumliuk began reporting from Crimea because he saw what was taking place there as a continuation of the war in Donbass. “It’s a lot more important than it seems at first glance and offers some understanding into what happened after the breakup of the Soviet Union and what will happen to such a big territory, in places like Belarus and Kazakhstan,” he said. He mostly covers court cases, with a focus on persecutions against Tatars. He says very few foreign outlets work with him regularly, they’ll only ask for his help if something happens.

“[Without constant coverage] it’s super difficult to understand the situation. There’s no human rights organisations working on the ground and very few independent journalists. Very little information on repression against political prisoners goes out. For this reason, it seems nothing is happening in Crimea. It’s all very quiet. But if you speak with Tatars the picture changes. A majority of kids live without their father because of what has been happening,”Naumliuk said.

“I think that not enough journalists go, and that’s there’s not enough stories coming from Crimea, because of the travel,” Ola Cichowlas, who recently travelled via Ukraine to spend two days reporting in Crimea for the Agence France Presse, said in an interview.

“Meanwhile, the world has gotten tired of the story,” Pechonchyk said. Foreign journalists often come for the anniversary of the annexation, do a quick story and then leave.

According to the State Migration Service of Ukraine, 106 foreign journalists have travelled to Crimea via Ukraine between 2015 and March 2018.

In this context, the Human Rights Information Centre and other organisations have tried to push for a facilitated access for foreign journalists who travel to Crimea, but also for aid workers and lawyers for whom it can take much longer to obtain a permit. “The first issue in terms of access is security,” says Pechonchyk. “For a foreign journalist it’s safer to come to Crimea via the Russian Federation than enter via mainland Ukraine. You’re almost always interrogated by the FSB when you go via Ukraine, with a higher risk of being put under surveillance. If you fly to Crimea from Moscow you violate Ukrainian law but it’s safer.”

Pechonchyk believes the process enabling foreign journalists to travel to Crimea should be made simpler: “It shouldn’t be a permission, but a notification. People should be allowed to do it from abroad, via a consulate or an embassy through an online form, and they should be able to apply in English – it’s all in Ukrainian at the moment. This should be a multi-entry permit and the number of categories able to get it should be extended.” At the moment, the list only includes journalists, human rights defenders, people working for international organisations, travelling for religious purposes, to visit relatives or people who have relatives buried in Crimea. Researchers and filmmakers, for instance, are not included and struggle to go to Crimea legally.

Pechonchyk also believes there should be exceptional cases – emergencies – where journalists and lawyers are allowed to travel from Russia, to attend a trial, or report on an arrest, for instance. The existing legislation offers little clarity and seems to be mostly applied when Ukraine wants to punish individuals who supported the annexation, as happened in 2017 when they banned a Russian singer who was to take part in the Eurovision and had performed in Crimea.

But there seems to be little room for a debate on this in Ukrainian society at the moment. Difficulties of access also apply to journalists who visit the self-proclaimed separatist republics of Donetsk or Luhansk, who need a series of accreditations from the Ukrainian and the separatist side, are not supposed to enter the separatist republics from Russia, and can face backlash once they have travelled to the republic. This is what happened when in May 2016, personal information of journalists having visited DNR and LNR was leaked to Myrotvorets, a Ukrainian website known to be supported by Ukrainian police and secret services. The leak included journalists from more than 30 media outlets, who had been merely covering the war on the rebel side but were depicted by nationalists as “collaborating with terrorists”. No one was prosecuted for the leak.

Johann Bihr, who covers Eastern Europe for Reporters Without Borders, told Index: “It’s important that foreign journalists keep heading to Crimea and going back there. And we encourage Russia and Ukraine to facilitate access for journalists. If they fail to do so we face some kind of double penalty, where Crimea is abandoned by the international community because it has not been recognised and turns into an information black hole.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1525192972009-6f6057be-6973-0″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Apr 18 | Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100082″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]

Понедельник, 30 апреля 2018 г.

Мы, нижеподписавшиеся 26 международных правозащитных организации в сфере медиа и интернет-свобод, решительно осуждаем попытки Российской Федерации заблокировать интернет-мессенджер Telegram, результатом которых стали широкомасштабные нарушения свободы выражения мнения и доступа к информации, и в т.ч. массовая блокировка сторонних вебсайтов.

Мы призываем Россию остановить блокировку Telegram и прекратить беспрестанные нападки на свободу интернета в целом. Мы также призываем Организацию Объединенных Наций, Совет Европы, Организацию по безопасности и сотрудничеству в Европе, Европейский Союз, Соединенные Штаты Америки и другие заинтересованные правительства оспорить действия России и поддержать основополагающие права на свободу выражения мнения и неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете и вне его. Наконец, мы призываем интернет-компании противостоять необоснованным и неправовым требованиям, нарушающим права их пользователей.

Массовые перебои в работе интернета

13 апреля 2018 г. Таганский районный суд Москвы удовлетворил запрос Роскомнадзора о блокировке доступа к Telegram на основании того, что компания не исполнила датированное 2017 годом распоряжение передать ключи шифрования Федеральной службе безопасности (ФСБ). С того времени действия, предпринятые российскими органами власти с целью ограничить доступ к Telegram, привели к массовым перебоям в работе интернета, в т.ч.:

-

16-18 апреля 2018 года Роскомнадзор отдал указание о блокировке почти 20 миллионов IP-адресов в попытке ограничить доступ к Telegram. Значительная часть заблокированных адресов принадлежит международным интернет-компаниям, в т.ч. Google, Amazon и Microsoft. В настоящее время XX из них остаются заблокированными.

-

Массовая блокировка IP-адресов негативно влияет на большое число сетевых сервисов, которые не имеют никакого отношения к Telegram, в числе прочего интернет-банкинг и сайты бронирования гостиниц, электронная коммерция и покупка авиабилетов.

-

Международная правозащитная группа Агора, представляющая Telegram в России, сообщила, что были получены запросы о помощи в связи с массовыми блокировками от около 60 компаний, включая интернет-магазины, службы доставки и разработчиков программного обеспечения.

-

По меньшей мере шесть интернет-СМИ (Петербургский дневник, Coda Story, FlashNord, FlashSiberia, Тайга.инфо, и 7×7) пострадали от временного ограничения доступа к их вебсайтам.

-

17 апреля 2018 года Роскомнадзор потребовал от Google и Apple удалить приложение Telegram из магазинов приложений, несмотря на отсутствие в российском законодательстве оснований для такого требования. Приложение на данный момент остается доступным, однако Telegram не может предоставить обновление для улучшения доступа через прокси-серверы.

-

Провайдеры виртуальных частных сетей (VPN), такие как TgVPN, Le VPN и VeeSecurity, также были заблокированы из-за предоставления альтернативных средств доступа к Telegram. Федеральный закон 276-ФЗ запрещает использование VPN и интернет-анонимайзеров для предоставления доступа к вебсайтам, заблокированным в России, и дает полномочия Роскомнадзору по блокировке любого сайта, объясняющего, как пользоваться такими сервисами.

История ограничительного законодательного регулирования интернета

В течение последних шести лет Россия приняла большое число законов, ограничивающих свободу выражения мнения и право на неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете. В их число входит создание в 2012 г. черного списка интернет-сайтов, администрируемого Роскомнадзором, и поэтапное расширение оснований для блокировки вебсайтов, включая блокировку без решения суда.

Принятый в 2016 году т.н. «закон Яровой», нацеленный на «борьбу с экстремизмом», налагает обязательства на всех операторов связи и интернет-провайдеров хранить метаданные пользователей, предоставлять ключи шифрования по запросу органов безопасности и использовать исключительно методы шифрования, одобренные российским правительством, на практике это означает создание «бэкдора» для сотрудников российских органов безопасности для доступа к данным, трафику и коммуникациями интернет-пользователей.

В октябре 2017 года мировой судья признал Telegram виновным в совершении административного правонарушения в связи с непредоставлением ключей шифрования российским властям, что, по заявлению компании, невозможно сделать в силу использования Telegram сквозного шифрования. На компанию был наложен штраф в размере 800 000 рублей. Апелляция Telegram по административному делу была отклонена в марте 2018 года, что дало российским органам власти формальные основания для блокировки Telegram в России в соответствии со статьей 15.4 Федерального закона «Об информации, информационных технологиях и о защите информации».

Недавние меры, принятые российскими органами власти в отношении Telegram, имеют серьезные последствия для свободы выражения мнения и права на неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете в России и по всему миру:

-

Для российских пользователей такие приложения, как Telegram и другие подобные сервисы, стремящиеся предоставить защищенную связь, критически важны для обеспечения безопасности. Они представляют собой важный источник информации о важнейших проблемах политической, экономической и общественной жизни, свободный от неоправданного вмешательства правительства. Для СМИ и журналистов в России и за ее пределами Telegram служит не только платформой для обмена сообщениями с целью безопасного общения с источниками, но и площадкой для публикаций. Telegram-каналы представляют собой средство передачи и распространения контента для СМИ и отдельных журналистов и блогеров. С учетом прямого и косвенного контроля со стороны государства в отношении многих традиционных российских СМИ и самоцензуры, которую многие другие СМИ считают необходимым применять, каналы мгновенного обмена сообщениями, такие как Telegram, стали ключевым средством распространения идей и мнений.

-

Компании, которые исполняют требования «закона Яровой», предоставляя правительствам «бэкдор» к своим сервисам, ставят под угрозу безопасность сетевых коммуникаций как своих российских пользователей, так и людей, с которыми они общаются за пределами страны. Журналисты особенно опасаются, что предоставление ФСБ доступа к данной информации поставит под угрозу их источники – краеугольный камень свободы печати. Исполнение компаниями требований закона также означает, что поставщики услуг связи готовы понижать стандарты шифрования и подвергать риску личную информацию и безопасность всех своих пользователей в качестве одной из издержек ведения бизнеса.

-

В июле 2018 года вступят в силу статьи «закона Яровой», требующие, чтобы компании хранили все голосовые и текстовые сообщения в течение шести месяцев и открывали к ним доступ органам безопасности в отсутствие решения суда. Это повлияет на общение людей в России и за ее границами.

Такие попытки российских органов власти контролировать сетевые коммуникации и ограничивать неприкосновенность частной жизни выходят далеко за границы необходимости и соразмерности в рамках борьбы с терроризмом и нарушают международное законодательство.

Международные стандарты

-

Блокировка вебсайтов или приложений представляет собой крайнюю меру, аналогичную запрету газеты или отзыву лицензии у телевизионной станции. Как таковая она с большой вероятностью в подавляющем большинстве случаев представляет собой несоразмерное вмешательство в свободу выражения мнения и свободу СМИ и должна подлежать строгому контролю. Любые меры по блокировке по меньшей мере должны быть четко сформулированы в рамках закона и требовать рассмотрения судом того, является ли полная блокировка доступа к онлайн-сервису необходимой и соответствует ли критериям, установленным и применяемым Европейским судом по правам человека. Блокировка Telegram и связанные с ней действия очевидным образом не соответствуют данному стандарту.

-

Различные требования «закона Яровой» явно противоречат международным стандартам в отношении шифрования и анонимности в соответствии с Докладом Специального докладчика по вопросу о поощрении и защите права на свободу мнений и их свободное выражение 2015 года (A/HRC/29/32). Специальный докладчик ООН лично обратился к российскому правительству, выразив серьезное беспокойство, относительно чрезмерных ограничений, налагаемых «законом Яровой» на права на свободу выражения мнения и на неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете. Европейский суд постановил, что подобные обязательства по хранению данных являются несовместимыми с Хартией Европейского Союза по правам человека. Хотя Европейский суд по правам человека пока не принял решение относительно совместимости положений российского законодательства о раскрытии ключей шифрования с Конвенцией о защите прав человека и основных свобод, он постановил, что российский правовой режим, регулирующий перехват сообщений, не обеспечивает адекватные и эффективные гарантии против произвола и риска злоупотреблений, присущих системе секретной слежки.

Мы, нижеподписавшиеся организации призываем:

-

Российские органы власти гарантировать интернет-пользователям право публиковать и читать информацию в интернете анонимно и обеспечить, чтобы любые ограничения анонимности в интернете производились по распоряжению суда и полностью соответствовали требованиям Статей 17 и 19(3) Международного пакта о гражданских и политических правах и Статей 8 и 10 Конвенции о защите прав человека и основных свобод, путем:

-

Отказа от блокировки Telegram и воздержания от истребования у сервисов обмена сообщениями, таких как Telegram, ключей шифрования с целью получения доступа к частной информации пользователей;

-

Отмены положений «закона Яровой», налагающих на интернет-провайдеров обязательство хранить все телекоммуникационные данные сроком до шести месяцев и требующих обязательного обеспечения «бэкдоров» шифрования, а также закона 2014 года о локализации персональных данных, предоставляющего органам безопасности легкий доступ к данным пользователей без достаточных мер защиты.

-

Отмены Федерального закона 241-ФЗ, запрещающего анонимность пользователей интернет-мессенджеров, и Закона 276-ФЗ, запрещающего VPN-сервисам и интернет-анонимайзерам предоставлять доступ к вебсайтам, запрещенным в России;

-

Внесения изменений в Федеральный закон 149-ФЗ «Об информации, информационных технологиях и о защите информации» с тем, чтобы процесс блокировки вебсайтов соответствовал международным стандартом. Всякое решение о блокировке доступа к вебсайту или приложению должно быть принято независимым судом и ограничено требованием необходимости и соразмерности законной цели. При рассмотрении запроса на блокировку суд или другой независимый судебный орган, в чьи полномочия входит принятие такого решения, должен рассмотреть его влияние на законный контент и возможность использования технологических средств для предотвращения излишней блокировки.

-

Представителей Организации Объединенных Наций, Совета Европы, Организации по безопасности и сотрудничеству в Европе, Европейского Союза, Соединенных Штатов Америки и других заинтересованных правительств внимательно рассмотреть и открыто оспорить действия России с целью защиты основополагающих прав на свободу выражения мнения и неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете и вне его, в соответствии с соглашениями, имеющими обязательную юридическую силу, стороной которых является Россия.

-

Интернет-компании противостоять требованиям, нарушающим международное право в области прав человека. Компании должны следовать Руководящим принципам предпринимательской деятельности в аспекте прав человека Организации Объединенных Наций, которые подчеркивают обязательство соблюдать права человека, применимое в рамках всей глобальной деятельности компании вне зависимости от места нахождения ее пользователей и исполнения государством своих обязательств в области защиты прав человека.

Подписи

-

ARTICLE 19

-

Международная Агора (Agora International)

-

Access Now

-

Amnesty International

-

Asociatia pentru Tehnologie si Internet – ApTI

-

Associação D3 – Defesa dos Direitos Digitais

-

Committee to Protect Journalists

-

Civil Rights Defenders

-

Electronic Frontier Foundation

-

Electronic Frontier Norway

-

Electronic Privacy Information Centre (EPIC)

-

Freedom House

-

Human Rights House Foundation

-

Human Rights Watch

-

Index on Censorship

-

International Media Support

-

Международное Партнерство за Права Человека (International Partnership for Human Rights)

-

ISOC Bulgaria

-

Open Media

-

Open Rights Group

-

ПЕН Америка (PEN America)

-

PEN International

-

Privacy International

-

Репортеры без границ (Reporters without Borders)

-

WWW Foundation

-

Xnet

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

We note with dismay the UK’s poor ranking in the latest Reporters Without Borders world press freedom index [“Secrets Act curbs hit UK ranking for press freedom”, April 25]. Index on Censorship has fought against censorship globally — and in defence of media freedom — for the past 46 years. It is galling to see the UK ranking only 40th among 180 countries, second-worst in Western Europe. It has dropped 18 places since the index began in 2002. Read in full.

30 Apr 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, Russia, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

We, the undersigned 26 international human rights, media and internet freedom organisations, strongly condemn the attempts by the Russian Federation to block the internet messaging service Telegram, which have resulted in extensive violations of freedom of expression and access to information, including mass collateral website blocking.

We call on Russia to stop blocking Telegram and cease its relentless attacks on internet freedom more broadly. We also call the United Nations (UN), the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the European Union (EU), the United States and other concerned governments to challenge Russia’s actions and uphold the fundamental rights to freedom of expression and privacy online as well as offline. Lastly, we call on internet companies to resist unfounded and extra-legal orders that violate their users’ rights.

Massive internet disruptions

On 13 April 2018, Moscow’s Tagansky District Court granted Roskomnadzor, Russia’s communications regulator, its request to block access to Telegram on the grounds that the company had not complied with a 2017 order to provide decryption keys to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). Since then, the actions taken by the Russian authorities to restrict access to Telegram have caused mass internet disruption, including:

- Between 16-18 April 2018, almost 20 million internet Protocol (IP) addresses were ordered to be blocked by Roskomnadzor as it attempted to restrict access to Telegram. The majority of the blocked addresses are owned by international internet companies, including Google, Amazon and Microsoft. Currently 14.6 remain blocked.

- This mass blocking of IP addresses has had a detrimental effect on a wide range of web-based services that have nothing to do with Telegram, including, but not limited to, online banking and booking sites, shopping, and flight reservations.

- Agora, the human rights and legal group, representing Telegram in Russia, has reported it has received requests for assistance with issues arising from the mass blocking from about 60 companies, including online stores, delivery services, and software developers.

- At least six online media outlets (Petersburg Diary, Coda Story, FlashNord, FlashSiberia, Tayga.info, and 7×7) found access to their websites was temporarily blocked.

- On 17 April 2018, Roskomnadzor requested that Google and Apple remove access to the Telegram app from their App stores, despite having no basis in Russian law to make this request. The app remains available, but Telegram has not been able to provide upgrades that would allow better proxy access for users.

- Virtual Private Network (VPN) providers – such as TgVPN, Le VPN and VeeSecurity proxy – have also been targeted for providing alternative means to access Telegram. Federal Law 276-FZ bans VPNs and internet anonymisers from providing access to websites banned in Russia and authorises Roskomnadzor to order the blocking of any site explaining how to use these services.

Background on restrictive internet laws

Over the past six years, Russia has adopted a huge raft of laws restricting freedom of expression and the right to privacy online. These include the creation in 2012 of a blacklist of internet websites, managed by Roskomnadzor, and the incremental extension of the grounds upon which websites can be blocked, including without a court order.

The 2016 so-called ‘Yarovaya Law’, justified on the grounds of “countering extremism”, requires all communications providers and internet operators to store metadata about their users’ communications activities, to disclose decryption keys at the security services’ request, and to use only encryption methods approved by the Russian government – in practical terms, to create a backdoor for Russia’s security agents to access internet users’ data, traffic, and communications.

In October 2017, a magistrate found Telegram guilty of an administrative offense for failing to provide decryption keys to the Russian authorities – which the company states it cannot do due to Telegram’s use of end-to-end encryption. The company was fined 800,000 rubles (approx. 11,000 EUR). Telegram lost an appeal against the administrative charge in March 2018, giving the Russian authorities formal grounds to block Telegram in Russia, under Article 15.4 of the Federal Law “On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection”.

The Russian authorities’ latest move against Telegram demonstrates the serious implications for people’s freedom of expression and right to privacy online in Russia and worldwide:

- For Russian users apps such as Telegram and similar services that seek to provide secure communications are crucial users’ safety. They provide an important source of information on critical issues of politics, economics and social life, free of undue government interference. For media outlets and journalists based in and outside Russia, Telegram serves not only as a messaging platform for secure communication with sources, but also as a publishing venue. Through its channels, Telegram acts as a carrier and distributor of content for entire media outlets as well as for individual journalists and bloggers. In light of the direct and indirect control the state has over many traditional Russian media and the self-censorship many other media outlets feel compelled to exercise, instant messaging channels like Telegram have become a crucial means of disseminating ideas and opinions.

- Companies that comply with the requirements of the ‘Yarovaya Law’ by allowing the government a back-door key to their services jeopardise the security of the online communications of their Russian users and the people they communicate with abroad. Journalists, in particular, fear that providing the FSB with access to their communications would jeopardize their sources, a cornerstone of press freedom. Company compliance would also signal that communication services providers are willing to compromise their encryption standards and put the privacy and security of all their users at risk, as a cost of doing business.

- Beginning in July 2018, other articles of the ‘Yarovaya Law’ will come into force requiring companies to store the content of all communications for six months and to make them accessible to the security services without a court order. This would affect the communications of both people in Russia and abroad.

Such attempts by the Russian authorities to control online communications and invade privacy go far beyond what can be considered necessary and proportionate to countering terrorism and violate international law.

International Standards

- Blocking websites or apps is an extreme measure, analogous to banning a newspaper or revoking the license of a TV station. As such, it is highly likely to constitute a disproportionate interference with freedom of expression and media freedom in the vast majority of cases and must be subject to strict scrutiny. At a minimum, any blocking measures should be clearly laid down by law and require the courts to examine whether the wholesale blocking of access to an online service is necessary and in line with the criteria established and applied by the European Court of Human Rights. Blocking Telegram and the accompanying actions clearly do not meet this standard.

- Various requirements of the ‘Yarovaya Law’ are plainly incompatible with international standards on encryption and anonymity as set out in the 2015 report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression report (A/HRC/29/32). The UN Special Rapporteur himself has written to the Russian government raising serious concerns that the ‘Yarovaya Law’ unduly restricts the rights to freedom of expression and privacy online. In the European Union, the Court of Justice has ruled that similar data retention obligations were incompatible with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Although the European Court of Human Rights has not yet ruled on the compatibility of the Russian provisions for the disclosure of decryption keys with the European Convention on Human Rights, it has found that Russia’s legal framework governing interception of communications does not provide adequate and effective guarantees against the arbitrariness and the risk of abuse inherent in any system of secret surveillance.

We, the undersigned organisations, call on:

- The Russian authorities to guarantee internet users’ right to publish and browse anonymously and ensure that any restrictions to online anonymity are subject to requirements of a court order, and comply fully with Articles 17 and 19(3) of the ICCPR, and articles 8 and 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, by:

- Desisting from blocking Telegram and refraining from requiring messaging services, such as Telegram, to provide decryption keys in order to access users private communications;

- Repealing provisions in the ‘Yarovaya Law’ requiring internet service providers (ISPs) to store all telecommunications data for six months and imposing mandatory cryptographic backdoors, and the 2014 Data Localisation law, which grant security service easy access to users’ data without sufficient safeguards.

- Repealing Federal Law 241-FZ, which bans anonymity for users of online messaging applications; and Law 276-FZ which prohibits VPNs and internet anonymisers from providing access to websites banned in Russia;

- Amending Federal Law 149-FZ “On Information, IT Technologies and Protection of Information” so that the process of blocking websites meets international standards. Any decision to block access to a website or app should be undertaken by an independent court and be limited by requirements of necessity and proportionality for a legitimate aim. In considering whether to grant a blocking order, the court or other independent body authorised to issue such an order should consider its impact on lawful content and what technology may be used to prevent over-blocking.

- Representatives of the United Nations (UN), the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organisation for the Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE), the European Union (EU) the United States and other concerned governments to scrutinise and publicly challenge Russia’s actions in order to uphold the fundamental rights to freedom of expression and privacy both online and offline, as stipulated in binding international agreements to which Russia is a party.

- Internet companies to resist orders that violate international human rights law. Companies should follow the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights, which emphasise that the responsibility to respect human rights applies throughout a company’s global operations regardless of where its users are located and exists independently of whether the State meets its own human rights obligations.

Signed by

- Article 19

- Agora International

- Access Now

- Amnesty International

- Asociatia pentru Tehnologie si Internet – ApTI

- Associação D3 – Defesa dos Direitos Digitais

- Committee to Protect Journalists

- Civil Rights Defenders

- Electronic Frontier Foundation

- Electronic Frontier Norway

- Electronic Privacy Information Centre (EPIC)

- Freedom House

- Human Rights House Foundation

- Human Rights Watch

- Index on Censorship

- International Media Support

- International Partnership for Human Rights

- ISOC Bulgaria

- Open Media

- Open Rights Group

- Pen America

- Pen International

- Privacy International

- Reporters without Borders

- WWW Foundation

- Xnetin

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1525093456273-1d231ece-6e3f-8″ taxonomies=”15″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

Britain leads the way in Europe – but not in a good way. It has a worse record on press freedom than all other European nation states except Italy, trailing others such as Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands. Read in full.

27 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

Poland is at the centre of the debate on memory politics in Europe. Plans for a museum to commemorate the ‘Polocaust’ are the next part of Poland’s history project – but have prompted outrage in Israel. Konstanty Gebert reports on what it all means. Read in full.

27 Apr 18 | Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

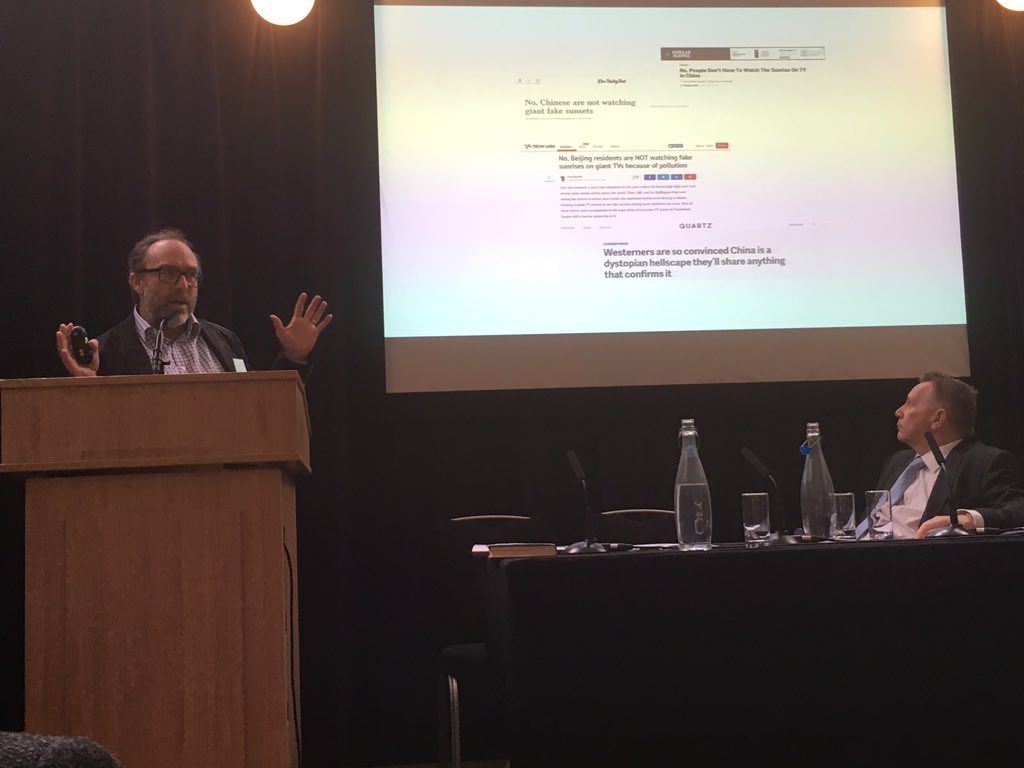

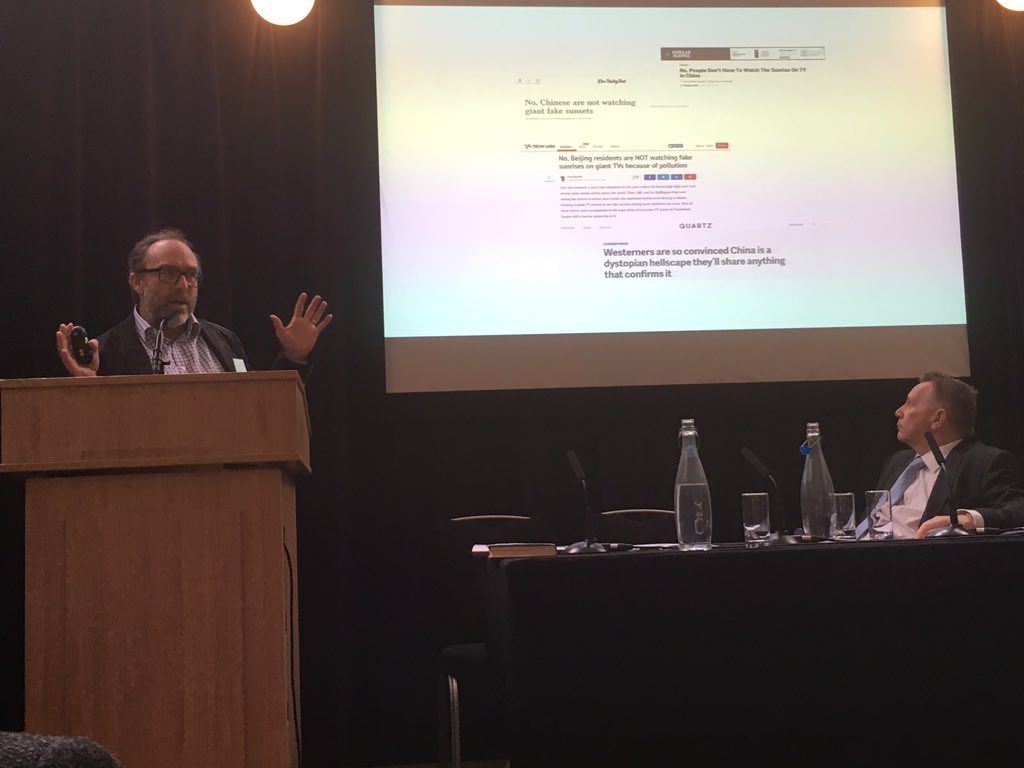

Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales speaking at Westminster Media Forum, April 2018. Credit: Daniel Bruce

“The advertising-only business model has been incredibly destructive for journalism,” said Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales at a Westminster Media Forum event on Thursday 26 April 2018 in London that looked at “fake news”.

“We need to resolve the incentives so that it makes sense and is financially sustainable to do good news,” Wales added.

Wales cited examples of false news stories that had been published on the Mail Online, such as an article featuring a projection of a perfect horizon in Beijing, erected as a way to compensate for the pollution, which proved fake, and a story claiming the Pope supported Donald Trump. He said the Daily Mail of 20 years ago was different. While not what he would choose to read, he thinks there is a place in the media landscape for tabloids, but one running fake news is “a quantum leap we should be very concerned about”.

Suggesting alternatives to advertising-only models, Wales said the Guardian’s donation request box (which he admitted he had consulted on) was an excellent example of how a media organisation can earn money without compromising standards. Meanwhile, a total paywall was very beneficial for some media, in particular financial media, with those readers valuing inside knowledge on the markets, though it would not suit all (the Guardian’s Snowden files, for example, were information he said he would want everyone to be able to access at the same time).

Wales’s concerns about the advertising-only, clickbait-style media models were echoed by others throughout the conference. Drawing an impressive panel of industry experts across media, law and tech, they all united in the view that while fake news meant a myriad of things to many different people, and was not something new, it was nevertheless problematic. Mark Borkowski, founder and head of Borkowski PR, spoke of the 19th-century great moon hoax and how “everything is different and everything is the same” before adding: “The speed at which we expect to get information, without proper fact-checking, is a plague.”

Nic Newman from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism proposed different ways for media to gain more trust, of which “slowing down” was one. Richard Sambrook, former director of global news at the BBC and now director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff University, said the rise in the number of opinion pieces over evidenced-based journalism was because they were cheaper to commission.

Better education about what constitutes good quality, reliable media was another solution proposed.

“Audiences need better education and sensitivity around algorithms,” said Kathryn Geels, from Digital Catapult.

Katie Lloyd, who is development director at the BBC’s School Report and who runs workshops around the country educating school children into news literacy, said there was a sense of urgency and confusion when it came to the topic and that teachers feel like it really needs to be taught.

“Young people are on the one hand savvy and on the other not so much and need extra help,” said Lloyd, adding that of those children she had interacted with, most knew what fake news was in principle, but not how to spot it.

“When we started talking to teachers they said they didn’t have the tools and the skills to teach it,” she added, tapping into a point raised by head of home news and deputy head of newsgathering at Sky, Sarah Whitehead, who said media education was just as important for older people as it was for the young, as the world of online was not the domain of only one group.

Lloyd also explained that diversity was essential when it came to who was delivering news as people were more likely to trust news from those they could relate to. This was in response to an audience member saying they had spoken to school children who expressed that they respected news on Vice over the BBC. Lloyd agreed that it was essential for news organisations to have a wide range of people in terms of age and background. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524822984082-ad9d065c-d104-5″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Apr 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet has a history of tangling with the country’s governments.

We, the undersigned freedom of expression and human rights organisations, strongly condemn last night’s guilty verdicts for staff and journalists of Cumhuriyet newspaper and note the harsh sentences for the defendants. The verdict further demonstrates that Turkey’s justice system and the rule of law is failing: this was a trial where the ‘crime’ was journalism and the only ‘evidence’ was journalistic activities.

While three Cumhuriyet staff were acquitted, all the remaining journalists and executives were handed sentences of between 2 years, 6 months and 8 years, 1 month. Time already served in pretrial detention will likely be taken into consideration, however all will still have jail terms to serve, and those with the harshest sentences would still have to serve approximately 5 years. Travel bans have been placed on all defendants, barring the three that were acquitted, in a further attempt to silence them in the international arena.

Several of our organisations have been present to monitor and record the proceedings since the first hearing in July 2017. The political nature of the trial was clear from the outset and continued throughout the trial. The initial indictment charged the defendants with a mixture of terrorism and employment related offenses. However, the evidence presented did not stand the test of proof beyond reasonable doubt of internationally recognizable crimes. The prosecution presented alleged changes to the editorial policy of the paper and the content of articles as ‘evidence’ of support for armed terrorist groups. Furthermore, despite 17 months of proceedings, no credible evidence was produced by the prosecution during the trial.

The indictment, the pre-trial detention and the trial proceedings violated the human rights of the defendants, including the right to freedom of expression, the right to liberty and security and the right to a fair trial. Furthermore, the symbolic nature of this trial against Turkey’s most prominent opposition newspaper undoubtedly has a chilling effect on the right to free expression much more broadly in Turkey and restricts the rights of the population to access information and diverse views.

“We observed violations of the right to a fair trial throughout the hearings. Despite the defence lawyers arguing that the basic requirements for a fair trial, such as an evidence-based indictment, were lacking these arbitrary sentences were handed down in order to attempt to intimidate one of the last remaining bastions of the independent press in Turkey,” said Turkey Advocacy Coordinator, Caroline Stockford.

The defence team repeatedly relied on the rights enshrined in the Turkish Constitution, as well as the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, demonstrating the importance of European human rights law to Turkey’s domestic legal system.

“‘Journalism is not a crime’ was declared again and again by the defendants and their lawyers and yet, despite the accusations containing no element of crime, the defendants served a collective total of 9.5 years in pretrial detention, and were found guilty at the end of an unfair trial,” said Jennifer Clement, President of PEN International.

Speedy rulings on legal cases of Turkish journalists, which include the Cumhuriyet cases of Murat Sabuncu and others and staff writer Ahmet Şık cases, pending before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) are crucial. This is not only to redress the rights violations of the many journalists still languishing in detention, but also to defend the independence and impartiality of the judiciary itself in Turkey. The Cumhuriyet case and other prominent trials against journalists clearly demonstrate that the rule of law is totally compromised in Turkey then there is little hope for fair or speedy domestic judicial recourse for any defendant.

“The short three hours of deliberation by the judicial panel did not give the impression that the case was taken seriously. The 17 months during which there have been 7 hearings of this utterly groundless trial have damaged independent journalism in Turkey at a time when over 90% of the media is under the sway of the administration,” said Nora Wehofsits, Advocacy Officer, European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF).

The guilty verdicts against the Cumhuriyet journalists and executives must be overturned and the persecution of all other journalists and others facing criminal charges merely for doing their job and peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression must be stopped. The authorities must immediately lift the state of emergency and return to the rule of law. The independence of the Turkish courts must be reinstated, enabling it to act as a check on the government, and hold it accountable for the serious human rights violations it has committed and continues to commit.

In light of the apparent breakdown of the rule of law and the fact that Turkish courts are evidently unable to deliver justice, we also call on the ECtHR to fulfil its role as the ultimate guardian of human rights in Europe, and to rule swiftly on the free expression cases currently pending before it and provide an effective remedy for the severe human rights violations taking place in Turkey.

Furthermore, we call on the institutions of the Council of Europe and its member states to remind Turkey of its international obligation to respect and protect human rights, in particular the right to freedom of expression and the right to a fair trial, and to give appropriate priority to these issues in their relations with Turkey, both in bilateral and multilateral forums. In addition, the Council of Europe’s member states should provide adequate support to the ECtHR.

We also call on the European and International media to continue to support their Turkish colleagues and to give space to dissenting voices who are repressed in Turkey.

Amnesty International

Article 19

Articolo 21

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI)

English PEN

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

Freedom House

Global Editors Network

Index on Censorship

Initiative for Freedom of Expression

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

International Press Institute (IPI)

Italian Press Federation

Norwegian PEN

Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso – Transeuropa

Ossigeno per l’informazione

PEN America

PEN Belgium-Flanders

PEN Centre Germany

PEN Canada

PEN International

PEN Netherlands

Platform for Independent Journalism (P24)

Reporters without Borders

Research Institute on Turkey

South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

WAN-ifra[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Apr 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Brussels, 26 April 2018

OPEN LETTER IN LIGHT OF THE 27 APRIL 2018 COREPER I MEETING

Your Excellency Ambassador, cc. Deputy Ambassador,

We, the undersigned, are writing to you ahead of your COREPER discussion on the proposed Directive on copyright in the Digital Single Market.

We are deeply concerned that the text proposed by the Bulgarian Presidency in no way reflects a balanced compromise, whether on substance or from the perspective of the many legitimate concerns that have been raised. Instead, it represents a major threat to the freedoms of European citizens and businesses and promises to severely harm Europe’s openness, competitiveness, innovation, science, research and education.

A broad spectrum of European stakeholders and experts, including academics, educators, NGOs representing human rights and media freedom, software developers and startups have repeatedly warned about the damage that the proposals would cause. However, these have been largely dismissed in rushed discussions taking place without national experts being present. This rushed process is all the more surprising when the European Parliament has already announced it would require more time (until June) to reach a position and is clearly adopting a more cautious approach.

If no further thought is put in the discussion, the result will be a huge gap between stated intentions and the damage that the text will actually achieve if the actual language on the table remains:

- Article 13 (user uploads) creates a liability regime for a vast area of online platforms that negates the E-commerce Directive, against the stated will of many Member States, and without any proper assessment of its impact. It creates a new notice and takedown regime that does not require a notice. It mandates the use of filtering technologies across the board.

- Article 11 (press publisher’s right) only contemplates creating publisher rights despite the many voices opposing it and highlighting it flaws, despite the opposition of many Member States and despite such Member States proposing several alternatives including a “presumption of transfer”.

- Article 3 (text and data mining) cannot be limited in terms of scope of beneficiaries or purposes if the EU wants to be at the forefront of innovations such as artificial intelligence. It can also not become a voluntary provision if we want to leverage the wealth of expertise of the EU’s research community across borders.

- Articles 4 to 9 must create an environment that enables educators, researchers, students and cultural heritage professionals to embrace the digital environment and be able to preserve, create and share knowledge and European culture. It must be clearly stated that the proposed exceptions in these Articles cannot be overridden by contractual terms or technological protection measures.

- The interaction of these various articles has not even been the subject of a single discussion. The filters of Article 13 will cover the snippets of Article 11 whilst the limitations of Article 3 will be amplified by the rights created through Article 11, yet none of these aspects have even been assessed.

With so many legal uncertainties and collateral damages still present, this legislation is currently destined to become a nightmare when it will have to be transposed into national legislation and face the test of its legality in terms of the Charter of Fundamental Rights and the Bern Convention.

We hence strongly encourage you to adopt a decision-making process that is evidence-based, focussed on producing copyright rules that are fit for purpose and on avoiding unintended, damaging side effects.

Yours sincerely,

The over 145 signatories of this open letter – European and global organisations, as well as national organisations from 28 EU Member States, represent human and digital rights, media freedom, publishers, journalists, libraries, scientific and research institutions, educational institutions including universities, creator representatives, consumers, software developers, start-ups, technology businesses and Internet service providers.

EUROPE

1. Access Info Europe

2. Allied for Startups

3. Association of European Research Libraries (LIBER)

4. Civil Liberties Union for Europe (Liberties)

5. Copyright for Creativity (C4C)

6. Create Refresh Campaign

7. DIGITALEUROPE

8. EDiMA

9. European Bureau of Library, Information and Documentation Associations (EBLIDA)

10. European Digital Learning Network (DLEARN)

11. European Digital Rights (EDRi)

12. European Internet Services Providers Association (EuroISPA)

13. European Network for Copyright in Support of Education and Science (ENCES)

14. European University Association (EUA)

15. Free Knowledge Advocacy Group EU

16. Lifelong Learning Platform

17. Public Libraries 2020 (PL2020)

18. Science Europe

19. South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

20. SPARC Europe

AUSTRIA

21. Freischreiber Österreich

22. Internet Service Providers Austria (ISPA Austria)

BELGIUM

23. Net Users’ Rights Protection Association (NURPA)

BULGARIA

24. BESCO – Bulgarian Startup Association

25. BlueLink Foundation

26. Bulgarian Association of Independent Artists and Animators (BAICAA)

27. Bulgarian Helsinki Committee

28. Bulgarian Library and Information Association (BLIA)

29. Creative Commons Bulgaria

30. DIBLA

31. Digital Republic

32. Hamalogika

33. Init Lab

34. ISOC Bulgaria

35. LawsBG

36. Obshtestvo.bg

37. Open Project Foundation

38. PHOTO Forum

39. Wikimedians of Bulgaria

CROATIA

40. Code for Croatia

CYPRUS

41. Startup Cyprus

CZECH REPUBLIC

42. Alliance pro otevrene vzdelavani (Alliance for Open Education)

43. Confederation of Industry of the Czech Republic

44. Czech Fintech Association

45. Ecumenical Academy

46. EDUin

DENMARK

47. Danish Association of Independent Internet Media (Prauda) ESTONIA

48. Wikimedia Eesti

FINLAND

49. Creative Commons Finland

50. Open Knowledge Finland

51. Wikimedia Suomi

FRANCE

52. Abilian

53. Alliance Libre

54. April

55. Aquinetic

56. Conseil National du Logiciel Libre (CNLL)

57. France Digitale

58. l’ASIC

59. Ploss Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (PLOSS-RA)

60. Renaissance Numérique

61. Syntec Numérique

62. Tech in France

63. Wikimédia France

GERMANY

64. Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Medieneinrichtungen an Hochschulen e.V. (AMH)

65. Bundesverband Deutsche Startups

66. Deutscher Bibliotheksverband e.V. (dbv)

67. eco – Association of the Internet Industry

68. Factory Berlin

69. Initiative gegen ein Leistungsschutzrecht (IGEL)

70. Jade Hochschule Wilhelmshaven/Oldenburg/Elsfleth

71. Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT)

72. Landesbibliothekszentrum Rheinland-Pfalz

73. Silicon Allee

74. Staatsbibliothek Bamberg

75. Ubermetrics Technologies

76. Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt (Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg)

77. University Library of Kaiserslautern (Technische Universität Kaiserslautern)

78. Verein Deutscher Bibliothekarinnen und Bibliothekare e.V. (VDB)

79. ZB MED – Information Centre for Life Sciences

GREECE

80. Greek Free Open Source Software Society (GFOSS)

HUNGARY

81. Hungarian Civil Liberties Union

82. ICT Association of Hungary – IVSZ

83. K-Monitor

IRELAND

84. Technology Ireland

ITALY

85. Hermes Center for Transparency and Digital Human Rights

86. Istituto Italiano per la Privacy e la Valorizzazione dei Dati

87. Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights (CILD)

88. National Online Printing Association (ANSO)

LATVIA

89. Startin.LV (Latvian Startup Association)

90. Wikimedians of Latvia User Group

LITHUANIA

91. Aresi Labs

LUXEMBOURG

92. Frënn vun der Ënn

MALTA

93. Commonwealth Centre for Connected Learning

NETHERLANDS

94. Dutch Association of Public Libraries (VOB)

95. Kennisland

POLAND

96. Centrum Cyfrowe

97. Coalition for Open Education (KOED)

98. Creative Commons Polska

99. Elektroniczna BIBlioteka (EBIB Association)

100. ePaństwo Foundation

101. Fundacja Szkoła z Klasą (School with Class Foundation)

102. Modern Poland Foundation

103. Ośrodek Edukacji Informatycznej i Zastosowań Komputerów w Warszawie (OEIiZK)

104. Panoptykon Foundation

105. Startup Poland

106. ZIPSEE

PORTUGAL

107. Associação D3 – Defesa dos Direitos Digitais (D3)

108. Associação Ensino Livre

109. Associação Nacional para o Software Livre (ANSOL)

110. Associação para a Promoção e Desenvolvimento da Sociedade da Informação (APDSI)

ROMANIA

111. ActiveWatch

112. APADOR-CH (Romanian Helsinki Committee)

113. Association for Technology and Internet (ApTI)

114. Association of Producers and Dealers of IT&C equipment (APDETIC)

115. Center for Public Innovation

116. Digital Citizens Romania

117. Kosson.ro Initiative

118. Mediawise Society

119. National Association of Public Librarians and Libraries in Romania (ANBPR)

SLOVAKIA

120. Creative Commons Slovakia

121. Slovak Alliance for Innovation Economy (SAPIE)

SLOVENIA

122. Digitas Institute

123. Forum za digitalno družbo (Digital Society Forum)

SPAIN

124. Asociación de Internautas

125. Asociación Española de Startups (Spanish Startup Association)

126. MaadiX

127. Sugus

128. Xnet

SWEDEN

129. Wikimedia Sverige

UK

130. Libraries and Archives Copyright Alliance (LACA)

131. Open Rights Group (ORG)

132. techUK

GLOBAL

133. ARTICLE 19

134. Association for Progressive Communications (APC)

135. Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT)

136. COMMUNIA Association

137. Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA)

138. Copy-Me

139. Creative Commons

140. Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

141. Electronic Information for Libraries (EIFL)

142. Index on Censorship

143. International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR)

144. Media and Learning Association (MEDEA)

145. Open Knowledge International (OKI)

146. OpenMedia

147. Software Heritage

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524750347203-f1e70660-87dd-9″ taxonomies=”1908″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

The brutal killings of investigative journalists Daphne Caruana Galizia and Ján Kuciak came as tragic reminders that Europe remains a dangerous place for journalists. How European states respond to these murders will shape not only the future of the press, but also that of our democracies. Read the full article

25 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

In the months since Donald Trump was elected President of the United States, protesters have taken to the streets to march with signs and chant their frustration; Trump himself has lashed out at criticism, calling critical media the “fake news” and threatening broadcast licenses; and the nation’s most popular sport has been gripped by debate over players who “take a knee” to protest police brutality. Read the full article.

25 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

Jeudi 19 avril, l’association internationale de défense de la liberté d’expression Index on Censorship a remis ses prix 2018 dans quatre catégories, arts, Campagne de sensibilisation, Militantisme en ligne et Journalisme, respectivement au Museum of Dissidence à Cuba, à l’ONG Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, au collectif de blogueurs congolais Habari RDC et la journaliste hondurienne Wendy Funes. Read the full article.