25 Apr 18 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100019″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]In the wake of the 15 July 2016 coup attempt, Turkey has become a “de facto permanent” emergency regime. The state of emergency, which has been extended six times, has become a convenient pretext for the government to crack down on freedom of expression.

The resultant purge has had draconian impacts: 5,822 academics sacked, 189 media outlets shuttered and 319 journalists arrested or prosecuted. The country’s judicial system has been decimated, with 4,560 judges and prosecutors dismissed. The government’s near-complete takeover of the judiciary and its direct defiance of the rule of law has debased freedom of expression in the country.

Examples of how the executive arm of the Turkish government is pulling the strings of the judiciary are not hard to find.

“Public indignation”

On 31 March 2017, the chief judge and two members of the Istanbul 25th High Criminal Court, who ordered the release of 21 journalists, and the prosecutor, who requested the releases, were suspended and later faced a disciplinary hearing. The 21 journalists were kept waiting in a prison van until a new arrest and detention order was issued by another court, which was under an onslaught of attacks from pro-government social media accounts.

Judicial Council deputy president Mehmet Yilmaz explained the reasoning behind the suspension of the judges: “The evidence has not been collected…and the release decision issued…has caused public indignation and harmed public conscience.”

If members of the judiciary can be suspended because their decision has caused “public indignation and harmed public conscience”, this suggests that judges in Turkey are without any protection from external pressures.

In another case, on 31 January 2018, a court ordered the release of Amnesty International’s Turkey chair Taner Kilic, but just hours later another demanded his re-arrest. Amnesty’s secretary general Salil Shetty said: “Over the last 24 hours, we have borne witness to a travesty of justice of spectacular proportions. To have been granted release only to have the door to freedom so callously slammed in his face is devastating for Taner, his family and all who stand for justice in Turkey.”

Taner’s renewed detention came after a decision from the Istanbul trial court to conditionally release him before his trial. However, after the prosecutor appealed, a second court in Istanbul accepted this appeal and quashed Taner’s release.

“I do not know why I was imprisoned a year ago and why I was released”

In another example of government interference, Turkish-German journalist Deniz Yücel, who reported for Die Welt newspaper, was arrested on 27 February 2017 in Istanbul. At the time, Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, summarised the accusations against Yücel saying: “He is not a correspondent; he is a terrorist. … This person hid in German consulate for a month as a representative of PKK, as a German spy. We have recordings, everything. This is the very spy terrorist.”

Erdogan also reportedly said that Yücel would not be released so long as he was the president. Yücel’s detention continued for almost a year without charge.

On the eve of his official trip to Germany on 15 February 2018, prime minister Binali Yildirim responded to protests and open requests from the German government for Yucel’s release. He said: “I think that a development will take place soon.” In a joint press conference with German chancellor Angela Merkel on 15 February 2018, he said: “What is necessary shall be done within the scope of the rule of law; what is required of us is to clear the way for the courts. … I hope that the trial will take place within a short time and a result will be achieved.”

On 16 February 2018 the Istanbul High Criminal Court accepted an indictment against Yücel that sought an 18-year sentence, yet the court also simultaneously ordered his release. Yücel flew to Germany on the same day. No international travel ban was imposed, despite the high sentence the prosecutor was demanding, which is the regular practice in “terror” related cases.

After his release, Yücel reported that he was given a 13 February 2018 ruling by the Third Criminal Peace Judgeship which detailed an order for his continued detention. “I am free despite this. I do not know why I was imprisoned a year ago and why I was released today. Is it not strange? Anyway, it does not matter. After all, I know that neither my jailing — more precisely my being taken as a hostage a year ago — nor my release today is in accordance with the rule of law at all. I know this very well.”

It’s clear that Yücel’s release and ability to leave the country were the result of political deals and the high criminal court was taking orders from the executive branch of government.

“Attempting to overthrow the constitutional order”

Within hours after Yücel’s release, six other individuals, including five journalists, were issued life sentences for “attempting to overthrow the constitutional order”. Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan, Nazli Ilicak, Yakup Şimşek, Fevzi Yazıcı and Şükrü Tuğrul Özsengül were all handed sentences after being convicted of involvement with the attempted coup, despite a clear lack of direct evidence.

“The court decision condemning journalists to aggravated life in prison for their work, without presenting substantial proof of their involvement in the coup attempt or ensuring a fair trial, critically threatens journalism and with it the remnants of freedom of expression and media freedom in Turkey,” said David Kaye, the United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression.

The constitutional court decided on 11 January 2018 that the freedom of expression and liberty of the two journalists Mehmet Altan and Şahin Alpay had been violated. Following the decision, deputy prime minister and government spokesperson Bekir Bozdağ stated on his Twitter account that the constitutional court had overstepped its boundary drawn up by the constitution and legislation. Under pressure from the government, the decisions made in the cases of Alpay and Altan were not implemented by Istanbul courts. This was due to almost the same reasoning as used by the government spokesperson.

Despite the dictum that the court’s decisions are final and binding on the legislative, executive and judicial matters, the courts of the first instance have not implemented the decision.

Another disappointment for the freedom of all arrested journalists

In another case, after an application by journalist Sahin Alpay, the constitutional court delivered the decision on 19 March 2018 that found Alpay’s rights were violated under the European Convention on Human Rights. By contrast, the Istanbul court followed the ruling this time and issued Alpay’s conditional release. Surprisingly, nothing was heard from the executive on this occasion. This development has been regarded by some as the government’s tactical move to avoid a possible European Court of Human Rights ruling on related pending cases to the effect that the constitutional court is not an effective remedy.

Turkish human rights lawyer Kerem Altıparmak tweeted that the Turkish government’s move was intended to send a message to the ECtHR that the constitutional court is a viable domestic remedy. Yaman Akdeniz, another prominent law professor and rights defender, said that ECtHR’s rejection of examination of the cases of journalists relying on the Article 18 of the European Convention on Human Rights is another disappointment for the freedom of all arrested journalists.

“A disgrace to Turkey’s justice system”

On 9 March 2018 a Turkish court sentenced 25 journalists to imprisonment on the grounds of allegedly being members of a terrorist organisation. The prosecutor’s primary evidence was that the journalists had criticised the Turkish government and Erdogan on social media. On these charges, 23 of the accused journalists were given between two and seven years in prison. Nina Ognianova, the Committee to Protect Journalists Europe and Central Asia programme co-ordinator, described the decision as “a disgrace to Turkey’s justice system”. She called on authorities to drop the charges on appeal.

The judiciary’s exposure to outside influences and pressures have turned the Turkish judicial system into a nightmare for journalists, academics, rights defenders, philanthropists and even judges themselves.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524736212391-dfe96d06-6795-2″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Apr 18 | Press Releases

A public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba and a collective of young bloggers and web activists who give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo are among the winners of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards.

The winners, who were announced on Thursday evening at a gala ceremony in London, also include one of the only human rights organisations still operating in Egypt and an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country.

Awards were presented in four categories: arts, campaigning, digital activism and journalism.

The winners are: Cuban art collective The Museum of Dissidence (arts); the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (campaigning); Habari RDC, a collective of young Congolese bloggers and activists (digital activism); and Honduran investigative journalist Wendy Funes (journalism).

From right: Human rights defenders Mohamed Sameh and Ahmad Abdallah of 2018 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award-winning Egypt Commission on Rights and Freedoms; 2018 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award-winning Honduran investigative journalist Wendy Funes; Congolese digital activist Guy Muyembe of 2018 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award-winning Habari RDC; Perla Hinojosa, Fellowship and Advocacy Officer at Index on Censorship, holds the 2018 Freedom of Expression Arts Award for Cuban arts collective Museum of Dissidence, who could not attend the Freedom of Expression Awards. (Photo: Index on Censorship)

“These winners deserve global recognition for their amazing work,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “Like all those nominated, they brave massive personal and political hurdles simply so that others can express themselves freely.”

Drawn from more than 400 public nominations, the winners were presented with their awards at a ceremony at The Mayfair Hotel, London, hosted by “stand-up poet” Kate Fox.

Actors, writers and musicians were among those celebrating with the winners. The guest list included The Times columnist and Chair of Index David Aaronovitch, BBC presenter Jonathan Dimbleby, comedian Shazia Mirza, social human rights activists Nimco Ali and Sara Khan, Serpentine Galleries CEO Yana Peel, poet Sabrina Mahfouz, Channel 4’s Lindsey Hilsum and more.

Winners were presented with cartoons created by Khalid Albaih, a Romanian-born Sudanese social media based political cartoonist who considers himself a virtual revolutionist.

Each of the award winners will become part of the fourth cohort of Freedom of Expression Awards fellows. They join last year’s winners — Chinese political cartoonist Rebel Pepper (arts); Russian human rights activist Ildar Dadin (campaigning); Digital collective Turkey Blocks (digital activism); news outlet Maldives Independent and its former editor Zaheena Rasheed (journalism) — as part of a world-class network of campaigners, activists and artists sharing best practices on tackling censorship threats internationally.

Through the fellowship, Index works with the winners – both during an intensive week in London and the rest of the awarding year – to provide longer term, structured support. The goal is to help winners maximise their impact, broaden their support and ensure they can continue to excel at fighting free expression threats on the ground.

This year’s panel of judges included Razia Iqbal, a journalist for BBC News, Tim Moloney QC, deputy head of Doughty Street Chambers, Yana Peel, CEO of the Serpentine Galleries, and Eben Upton CBE, a founder of the Raspberry Pi Foundation and CEO of Raspberry Pi.

Awards judge Eben Upton said: “”The ability to speak freely is a key foundation of democratic society and the rule of law: absent the ability to openly identify the abuse of power, extractive economic conditions, and exclusive political institutions, proliferate. This is why freedom of expression is so precious, and so often under attack from those in power.”

This is the 18th year of the Freedom of Expression Awards. Former winners include activist Malala Yousafzai, cartoonist Ali Ferzat, journalists Anna Politkovskaya and Fergal Keane, and Bahrain Center for Human Rights.

Ziyad Marar, President of Global Publishing at SAGE said: “The protection and promotion of free speech is a belief firmly entrenched within our values at SAGE. As both publisher of the magazine and sponsors of tonight’s awards, we are proud to support Index in their mission as they defend this right globally. We offer our warmest congratulations to those recognised and remain both humbled and awed by their inspirational achievements.”

Further details about the award winners are below.

For interviews with the award winners, who are in London until Friday 20 April, please contact Sean Gallagher at [email protected].

Photographs and other content related to the awards night will be available beginning 11am on Friday 20 April. Please contact Sean Gallagher at [email protected].

Index on Censorship is grateful for the support of the 2018 Freedom of Expression Awards sponsors: SAGE Publishing, Google, Private Internet Access, Edwardian Hotels, Vodafone, Vice News, Doughty Street Chambers and former Index Award-winning Psiphon.

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 – background on winners

Arts – The Museum of Dissidence (Cuba)

Perla Hinojosa, Fellowship and Advocacy Officer at Index on Censorship, holds the 2018 Freedom of Expression Arts Award for Cuban arts collective Museum of Dissidence, who could not attend the Freedom of Expression Awards. (Photo: Index on Censorship)

The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.

CEO of Serpentine Galleries and 2018 Freedom of Expression Award judge Yana Peel said: The Museum of Dissidence in Cuba is incredibly important for the safe space that it is providing for unsafe ideas. It is a tremendous platform through which the great artists of Cuba bring Cuba to the global stage.”

Profile

Campaigning – The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (Egypt). Award supported by Doughty Street Chambers

Human rights defenders Mohamed Sameh and Ahmad Abdallah of 2018 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award-winning Egypt Commission on Rights and Freedoms. (Photo: Index on Censorship)

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.

CEO of Raspberry Pi and Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 judge Eben Upton said: “In an environment when organisations have had to step back or disappear altogether, they’ve managed to keep going and just that persistence over a period of time in a difficult environment is inspiring”.

Profile

Digital Activism – Habari RDC (Congo). Award sponsored by Private Internet Access

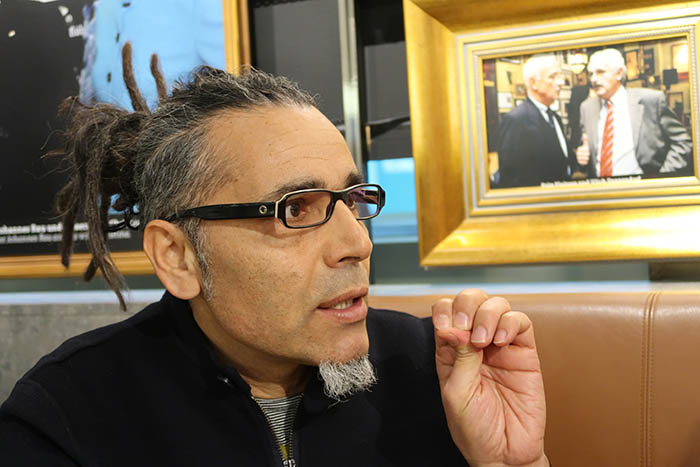

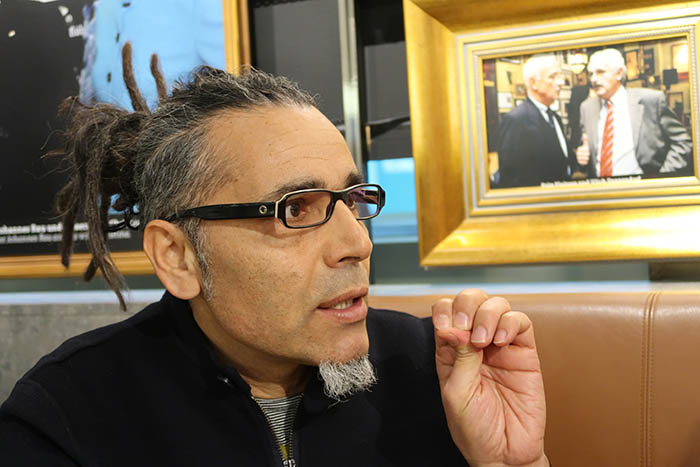

Congolese digital activist Guy Muyembe of 2018 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award-winning Habari RDC (Photo: Index on Censorship)

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.

Journalist and 2018 Freedom of Expression Awards judge Razia Iqbal aid: “They’re doing something which is actually very hard to do, which is make sure that the future generation know what’s happening in their own country, are willing to speak to each other about it and be active politically”.

Profile

Journalism – Wendy Funes (Honduras). Award sponsored by VICE News

2018 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award-winning Honduran investigative journalist Wendy Funes. (Photo: Index on Censorship)

Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.

Journalist and 2018 Freedom of Expression Awards judge Razia Iqbal QC said: “She is courageous in the face of death threats. She is courageous in the face of censorship. She is courageous just in terms of getting up every morning and saying I’m going to continue to do what I am doing.”

Profile

ABOUT THE FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIP

The Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards recognise those individuals and groups making the greatest impact in tackling censorship worldwide. Established 18 years ago, the awards shine a light on work being undertaken in defence of free expression globally. Often these stories go unnoticed or are ignored by the mainstream press. Through the fellowship, Index works with the winners – both during an intensive week in London and the rest of the awarding year – to provide longer term, structured support. The goal is to help winners maximise their impact, broaden their support and ensure they can continue to excel at fighting free expression threats on the ground.

ABOUT INDEX ON CENSORSHIP

Index on Censorship is a UK-based nonprofit that campaigns against censorship and promotes free expression worldwide. Founded in 1972, Index has published some of the world’s leading writers and artists in its award-winning quarterly magazine, including Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Samuel Beckett and Kurt Vonnegut. Index promotes debate, monitors threats to free speech and supports individuals through its annual awards and fellowship program.

23 Apr 18 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Academic Sharo Ibrahim Garip

Even before the attempted coup in July 2016, the situation for academics within Turkey was drastically changing.

Marking a turning point for the country’s political environment, the failed July 2016 coup was an attempt to oust president Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

In 2016 hundreds of academics were dismissed from their positions without notice, including sociologist Sharo Ibrahim Garip, who taught at Yuzuncu Yil University in the East Anatolian city of Van, Turkey.

A German national with Kurdish roots, Garip was dismissed from his position at the university in February 2016. Accused of spreading terrorist propaganda, he was arrested in January 2016 and placed under a two-year travel ban, after he signed a petition, along with 1,227 other academics, urging the Turkish government to end its crackdown on Kurdish communities in Turkey’s southeast.

The petition by Academics for Peace called for a peaceful situation to the conflict with the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK), a terrorist group seeking an independent Kurdish state within Turkey. Garip and the other academics denounced “war-like conditions” in the south-east and accused the government of an “extermination and expulsion policy” following the end of a ceasefire with the group and Turkish security forces in 2015. President Erdogan referred to them as “so-called intellectuals” and accused the signatories of “treason”.

Although there was no evidence Garip supported the group, he was still unable to leave the country or practice his profession, although his German citizenship prevented him from being detained pre-trial. Now working at the University of Essen-Duisburg, Garip spoke with Danyaal Yasin of Index on Censorship about his dismissal and the situation for academics following the coup.

Index: After you and hundreds of other academics were dismissed, what were your initial thoughts?

Sharo Ibrahim Garip: I was at the university. I received just a one-sentence decision from the university administration: “Mr Garip’s contract has been cancelled as the university no longer requires his services.” It was not surprising to me because I had already expected such an outcome. The history of the Turkish state is rife with instances of the elimination of political opposition, particularly critical thinkers such as academics and journalists. It was a planned action to eliminate critical thinkers from universities and the public sector. All those changes in the bureaucracy and public sector started before the military coup and continued following the civilian putsch. I could clearly observe the regime change in silence, but it was not possible to stop.

Index: Where were you when you found out? How did this affect you and your family?

Garip: I was detained on 15 January 2016 at the university in Van. I had to spend one night and one day in a jail cell of the special anti-terror unit of the police. I realised that I was a hostage from the beginning. I was threatened and humiliated during my interrogation. My family (who live mostly in Norway and Austria) was extremely concerned for my life. They still recall the events of the 1990s in Turkey, when many people were jailed/tortured or murdered, including the well-known cases of Hrant Dink and Tahir Elci, as well as many other intellectuals. The signatories have also been publicly exposed in the press and social media by government supporters and nationalists, leading to fears of reprisals from a mafia boss who declared that they will “spill the blood” of the signatories.

Index: What was the most difficult part?

Garip: I was removed from my academic position at Yuzuncu Yil (One Hundredth Year) University in Van in February 2016 because I had signed the petition by Academics for Peace, calling on the Turkish government to pursue a peaceful approach in its conflict with the Kurds, and in order to further punish me, the government forbade me to leave the country. I experienced a kind of structural violence, to live in Turkey without a job, health insurance, or a home. I shared a flat with friends for a while. I was trying to survive under very difficult conditions. I also experienced psychological violence. For example, all my phone calls were tapped and I was under regular surveillance. These had a very deep psychological effect on me. I didn’t want to meet with friends because I was constantly afraid of being attacked, imprisoned, killed, or tortured.

Under such circumstances is almost impossible to teach or produce any kind of academic work, write articles, do research, and so on.

It was painful to observe a country sink into political disaster again. Escalation of tensions, political collapse, and the war go back to the 90s, with civil war, political murders, missing people, bombing attacks on peaceful gatherings and meetings. It is also difficult to accept that at the moment approximately 70,000 students are in prison. One of my best students (who is only 22 years old) has been sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Index: Did you have to conceal your Kurdish heritage when studying or teaching?

Garip: No, I have never concealed my heritage. On the contrary, I disclosed my Kurdish heritage from the first day of teaching at the university in Van. Every day I talked to my students first in Kurdish and then continued in Turkish or sometimes in English. I arranged a Kurdish language course for sociology students as well. Kurds in Turkey have been assimilated for many years, a humiliating experience. Most Kurdish students have been psychologically damaged/traumatised by the violence perpetrated by the Turkish government. It was important to me to give my students a feeling of self-worth. This enabled me to establish a foundation of trust with my students, something not many other academics did.

Index: Why do you think academics are being brought to trial? What is the government’s goal?

Garip: It should be mentioned that Turkey has never, since its inception in 1921 until today, been a truly democratic country. Neither academic freedom nor freedom of speech has ever truly existed. The Turkish government has always thought of academics as well-paid public servants, a position which enjoys great privilege. Most Turkish academics have generally been loyal to the state and supported the official ideology. The petition for peace represented the first time that academics showed disloyalty to the state ideology, especially with regard to the Kurdish issue. For an authoritarian regime, such criticism was simply not acceptable. In this way, the government will punish academics. Turkey now appears to be inclined to go from an authoritarian regime to a totalitarian one. All undemocratic regimes try to maintain total control over society (the consolidation of institutional powers such as the NS regime). The masses must be repressed, and the media and intellectuals must be silenced and browbeaten. This is the goal of the government, which is why academics have been brought to trial. The academics have been punished in a number of different yet effective ways: dismissal, foreign travel bans, disciplinary processes.

Index: What has been the biggest change for academics in the country since the attempted coup?

Garip: The universities, schools, media, judiciary, and also parliament are now under the total control of the government. In particular, schools, the media, and universities have been shaped by a new ideology, which is both religious and nationalist. Many academics have been dismissed; more than 150,000 people in the public sector have lost their jobs. In the wake of the civilian putsch, 40,000 teachers, 8,247 academics, and 4,000 prosecutors and judges have been dismissed.

At universities, cultural events and demonstrations are forbidden. Students are not allowed to choose topics for their master or doctoral studies. At the moment four academics are in prison and another 15 academics and I have been sentenced to one year and three months in prison. Academics in Turkey are trying to survive; many of them live in very poor conditions. They have come up with new ideas such as establishing houses of culture or academies on the street. It is important to mention that academics and intellectuals all over the world, including Judith Butler, Etienne Balibar, and many other prominent academics have supported academics in Turkey. The quality of education is declining rapidly because many well-educated professors and instructors are leaving Turkey.

Index: Was there backlash from other academics when the petition came out?

Garip: Yes, at first. After the petition for peace came out, a petition titled “We support our government against terrorism” was signed by 5,000 academics. Some colleagues at the university definitely distanced themselves from me. The reason for this was partly ideological and partly out of fear. However, some academics supported me, as did most of my students.

Index: Do you feel the current climate will ever improve within the country?

Garip: I don’t like to be completely pessimistic but it is very difficult to expect much change within a short period. Possibly the situation may improve over the long term. At the moment we are confronted with a regime change and a government acting in desperation. Turkish society is extremely polarised and the political climate embittered. Structures within the government have been almost completely stripped down. It will be not easy to shift society from an authoritarian structure to a democratic one. We cannot forget that half of Turkey wants a secular and democratic government.

Index: You are now based in Germany – how does it feel to teach again?

Garip: It is wonderful. Here I enjoy a climate of freedom with my students. As I stated above, I have academic freedom and freedom of speech here which I wish my Turkish friends also had. While I was in Van, Turkey I invited many professors from London, Canada, and Germany to give lectures to my students via Skype. I wish to thank them for their excellent contributions. If I have the opportunity I would like to teach my students in Van from Germany via Skype as well.

Index: How has your work changed since leaving Turkey?

Garip: To be honest it was not easy to settle down. I had to start from the bottom again. But thanks to the social government and constitutional democracy in Germany, I was fortunate to receive help from many of my friends. I received a scholarship first for three months from the University of Essen-Duisburg and now have a fellowship from the University of Cologne. I am currently working on a research project. I have finished a new article and can publish it without fear. In short, I enjoy academic freedom and freedom of speech again. I wish all my friends in Turkey could enjoy such freedoms as well.

Index: Do you think you will ever return to Turkey?

Garip: Yes, of course I will. Travelling is an essential human right. I will visit my friends there or attend conferences and work on research projects.

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that “the intended coup was an attempt to protect the country’s democracy from president Recep Tayyip Erdogan”. This was updated on 24 April 2018[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524653051961-3c4f18a5-613b-9″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Apr 18 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Publicity photo from Behud – Beyond Belief by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti

To mark 50 years since the end of state theatre censorship in the UK, a team of actors led by Simon Callow will perform excerpts from a selection of canonical plays, and books adapted for the stage, that have been banned and censored in a variety of countries and time periods.

After the performance, there will be a panel discussion featuring leading figureheads in the industry, including director Lev Dodin, playwrights Christopher Hampton and Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti, free speech campaigner Jodie Ginsberg and theatre critic Michael Billington, discussing: Is Censorship Ever Good?

Since the beginning of theatrical history, governments and people has prevented the performance of play texts for political, social and cultural reasons. Directors and playwrights alike also frequently adapt banned and censored books for the stage – our event coincides with the premiere of Lev Dodin’s adaptation of Vasily Grossman’s once banned Life & Fate, and Christopher Hampton’s adaptation of Moliere’s once censored Tartuffe, both performing at the Haymarket this May.

In an era where freedom of speech if constantly reexamined, this event explores banned texts and the power of language and performance.

This event is presented by Belka Productions and the London tour of the Maly Drama Theatre with their production of Life & Fate, in collaboration with JW3.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Thursday 10 May 2018 7pm

Where: Theatre Royal Haymarket, 18 Suffolk Street, London SW1Y 4HT

Tickets: £15 via Theatre Royal Haymarket

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

Scottish YouTube personality Mark Meechan — also known to fans as ‘Count Dankula’ — has been given a £800 fine after recording a video of his girlfriend’s dog doing Nazi salutes. Read the full article

23 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

A YouTuber who trained his girlfriend’s dog to perform Nazi salutes has been fined £800 for being grossly offensive. Read the full article

23 Apr 18 | Awards, Digital Freedom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/Cc3K8Bcvt6Y”][vc_column_text] Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524476008020-fceb892e-6e72-0″ taxonomies=”23255″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524476008020-fceb892e-6e72-0″ taxonomies=”23255″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Apr 18 | Awards

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/mCmRy7htLos”][vc_column_text] Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475940373-94f7fdfa-5ff6-0″ taxonomies=”24389″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475940373-94f7fdfa-5ff6-0″ taxonomies=”24389″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Apr 18 | Awards, Digital Freedom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/ShavP70VY4o”][vc_column_text] The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475725322-09fdf4b1-d760-4″ taxonomies=”24136, 24135″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475725322-09fdf4b1-d760-4″ taxonomies=”24136, 24135″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Apr 18 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/-UpVto-2Sf0″][vc_column_text] The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.

The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475867242-0ea46ec1-56bd-1″ taxonomies=”23772″][awards_fellows years=”2018″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

Index on Censorship’s annual Freedom of Expression Awards last night drew journalists to the May Fair Hotel. David Aaronovitch chatted to Jonathan Dimbleby and AC Grayling, and Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg assured guests that the venue was a donation: “We promise we’re not spending your money on prosecco and chandeliers.” Read the full article

20 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

Alessio Perrone meets the activists shining light on human rights abuses during Egypt’s dark days. Read the full article

Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524476008020-fceb892e-6e72-0″ taxonomies=”23255″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Wendy Funes is an investigative journalist from Honduras who regularly risks her life for her right to report on what is happening in the country, an extremely harsh environment for reporters. Two journalists were murdered in 2017 and her father and friends are among those who have met violent deaths in the country – killings for which no one has ever been brought to justice. Funes meets these challenges with creativity and determination. For one article she had her own death certificate issued to highlight corruption. Funes also writes about violence against women, a huge problem in Honduras where one woman is killed every 16 hours.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524476008020-fceb892e-6e72-0″ taxonomies=”23255″][/vc_column][/vc_row] Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475940373-94f7fdfa-5ff6-0″ taxonomies=”24389″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Launched in 2016, Habari RDC is a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, who use Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to give voice to the opinions of young people from all over the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their site posts stories and cartoons about politics, but it also covers football, the arts and subjects such as domestic violence, child exploitation, the female orgasm and sexual harassment at work. Habari RDC offers a distinctive collection of funny, angry and modern Congolese voices, who are demanding to be heard.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475940373-94f7fdfa-5ff6-0″ taxonomies=”24389″][/vc_column][/vc_row] The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475725322-09fdf4b1-d760-4″ taxonomies=”24136, 24135″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms is one of the few human rights organisations still operating in a country which has waged an orchestrated campaign against independent civil society groups. Egypt is becoming increasingly hostile to dissent, but ECRF continues to provide advocacy, legal support and campaign coordination, drawing attention to the many ongoing human rights abuses under the autocratic rule of President Abdel Fattah-el-Sisi. Their work has seen them subject to state harassment, their headquarters have been raided and staff members arrested. ECRF are committed to carrying on with their work regardless of the challenges.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][awards_fellows years=”2018″][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524475725322-09fdf4b1-d760-4″ taxonomies=”24136, 24135″][/vc_column][/vc_row] The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.

The Museum of Dissidence is a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016 by acclaimed artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, their aim is to reclaim the word “dissident” and give it a positive meaning in Cuba. The museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana. Their fearlessness in opening dialogues and inhabiting public space has led to fierce repercussions: Nuñez was sacked from her job and Otero arrested and threatened with prison for being a “counter-revolutionary.” Despite this, they persist in challenging Cuba’s restrictions on expression.