13 Apr 18 | Artistic Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Glasgow School of Art. Credit: James Oberhelm

After the Glasgow School of Art censored an artwork by master of fine art student James Oberhelm from a May 2017 interim show when it was deemed to contain “inappropriate content”, the commitment of the world-famous institution to free speech has again come into question. Students enrolled in the programme were issued an updated handbook in November 2017 with provisions that would make such censorship much more likely and much easier to enforce in future.

These were without precedent, urging students to exercise caution when it comes to “offensive” or “inappropriate” material and warning against “bringing the institution into disrepute”. It goes on to say that the “right to freedom of speech is not absolute”, requiring students to adhere to the “highest ethical standards” and “ethical good practice”.

Over two-thirds of MFA students at the school have signed a petition calling for such rules to be removed and demanding an environment where they can work “free from the threat of being banned by GSA”. “Censorship is fundamentally a point of principle, even if it doesn’t affect an individual practice right now,” it adds.

Oberhelm is one of the 34 out of a total of 50 MFA students who have signed the recent petition. His artwork, “Effects” [The Enthronement], explored the geopolitics of the Middle East and included a propaganda video created by Isis. An email between staff members at the art school stated that Oberhelm’s “needs to be looked at by the Prevent Group”, referring to the UK’s counterterrorism legislation Prevent. Past and present staff at the institution have confirmed to Oberhelm that this was the first case of censorship in its history.

“It’s self-evident that open expression is fundamental to creative work and study,” he told Index. “The threat of censorship undermines open expression and the attempt to engender self-censorship is corrupting to art practice and to art education. Art is a space of potential and a discipline of vital exchange, not a tool for social engineering and ideological conformity.”

Henry Rogers, MFA programme leader at the school, replied to the signatories of the petition with the following [sic]: “we have as a team discussed petition about the ethical practice advisory statements in the MFA Handbook that some people have signed. Of course we are happy to look at this when preparing the 2018-2019 Handbook (normally a summer task for staff) and will consult you again at that point once the handbook has been revised. If there are any other amendment you feel you want to bring to the fore, please do let me know.”

“The MFA programme leader’s response is unsatisfactory in that it has simply delayed the decision until after this academic year ends, thus ensuring that an entire year of students, who have become well-informed about GSA’s advancing censorship practices, will be gone when a decision is made,” Oberhelm said. “While this delay of many months might come dressed in a procedural rationale, it also looks very much like the time-honoured institutional strategy of drawing out the process till the opposition dissipates.”

But Oberhelm remains hopeful that the Glasgow School of Art “still has the wherewithal to defend its reputation by removing these written directives, and ceasing the practice of briefing incoming postgrad students to police their art practice, rather than allow its reputation to become steadily more tarnished”.

Below is a list of works that likely wouldn’t be acceptable forms of expression under the Glasgow School of Art’s new rules and provisions:[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_media_grid grid_id=”vc_gid:1526900889337-d0a3a21c-65dc-2″ include=”99601,99606,99603,99605,99602,99604″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

UN Deputy Secretary General Amina J. Mohammed was in Abuja when her government illegally refouled 47 to Cameroon, where some face the death penalty. She said nothing at the time, and later issued a strange joint statement with her President Buhari, ignoring that he was responsible for the illegal refoulement. Read the full article.

12 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

Each year Index on Censorship honours activists who have been at the forefront of tackling censorship globally. Click hears from Jodie Ginsberg about some of nominees including creators of the Museum ofDissidence in Cuba. She is joined Guy Muyembe, from Habari RDC (a collective of young Congolese bloggers), to discuss digital activism. Watch the video.

12 Apr 18 | Awards, Fellowship 2018, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features

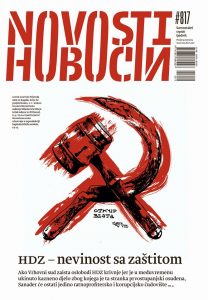

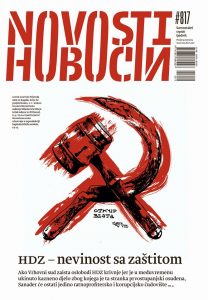

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/hKK5t6te-GE”][vc_column_text]Novosti weekly is a Serbian-language magazine in Croatia. It is run by journalists who are both Serbs and Croats, and are some of the most highly esteemed reporters in the country.

Although the weekly is fully funded as a Serb minority publication by the Serbian National Council, the paper deals with a whole range topics, not only those directly related to the minority status of Croatian Serbs, but also covering all the political, economic, social and cultural issues that are important for the Croatian society as a whole.

The paper’s journalists have come under intense pressure in the last year from Croatian nationalists with attacks and death threats that have been sanctioned by ultra-conservative forces in the country.

“As journalists we realise that our professional duty is to write truth, but because of the conditions in which we work, a significant part of our business has become the defence of the right to freedom of expression, without which truth is not possible,” said Novosti Weekly.

This is against a backdrop of a nationalist coalition government led by the conservative Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), which oversaw the sacking or demotion of 70 public broadcast journalists in the months after it came to power in January 2016.

Novosti irritates nationalists by writing about the things Croatian society is often silent on, for instance, the war crimes committed by the Croatian side during the Balkans war in the 1990s and the role of Croatian forces in the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It often uses satirical front covers to make its point.

The weekly also stands up for minorities, including LGBT groups, against the conservative forces of the Catholic Church and war veterans. One of their journalistic campaigns has been to challenge attempts by the far right to rehabilitate the Ustaše, the fascists who were in power in Croatia during World War II.

Novosti prides itself also on classic investigative journalism, which uncovers political and corporate corruption; and they do not shy away from exposing the pressure on editors and journalists from both censorship and self-censorship.

2017 was a year which saw the further rise in Croatia of right-wing extremism and ultra-conservative tendencies. Novosti weekly has been at the forefront of fighting the nationalist purges, becoming a forum for voices of resistance.

At the beginning of December 2016, Novosti broke a story about plans by the government, and veterans associations to install a memorial plaque with the World War II fascist slogan Za dom spremni (Ready for the Homeland) near the site of the former ustaše concentration camp at Jasenovac where more than 83,000 Serbs, Roma and Jews died.

Immediately after the release of the story in Novosti, the far-right political party A-HSP organised a protest under the windows of the magazine’s offices shouting, fascist slogans and anti-Serbian insults.

Some war veterans’ societies filed criminal charges against journalists, and others launched a series of private lawsuits against the publisher of the Novosti.

In August 2017, the extreme right piled on the pressure, accusing Croatian Serbs of setting the fires which burnt down forests in large parts of the Croatian coast during the summer.

They claimed Novosti Weekly had been encouraging the arsonists and Novosti received threats of violence – to shoot journalists and bomb the offices. The editorial team was told they would end up killed like Charlie Hebdo journalists.

The culmination of the summer of threats happened when the A-HSP organised another protest in front of Novosti’s offices and burnt copies of the magazine under the windows of the offices

“We would like to thank you for recognizing our work as well as for putting Novosti Weekly into the international spotlight after reaching the shortlist of the Freedom of Expression Awards,” said Novosti Weekly. “Your recognition means as much as the reactions of all relevant international journalistic organizations that stood in Weekly Novosti’s defense after facing pressure and threats for the work that we do. It’s a strong message of support that speaks volumes not only for all those who burnt out paper, but also to those who tried to ensure our destruction.”

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460×490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1523523750750-06e6cb2f-6ea9-6″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Apr 18 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is deeply concerned that the adoption of a “safe zone” around an abortion clinic in Ealing sets a dangerous precedent that could have far-reaching impacts on the right to protest and freedom of expression.

There are alternative legal remedies already on the books that can be used to police harassing and intimidating behaviour, as Ealing’s own options document pointed out.

The use of buffer zones to prevent protests could be used against all forms of speech – including those that wish to protest on environmental or political issues, for example.

As we wrote in our letter to the leader of the Ealing Council in March, the safe zones were potentially unlawful and disproportionate.

March 28 2018

Paul Najsarek

Ealing Council

Ealing W5 2HL

Dear Sir,

We have been advised by our lawyer that your consultation on exclusion zones was not open to non residents of the borough. But as a free speech organisation, we believe this has wider legal implications and should be open to a wider consultation.

We are, therefore, addressing this submission and letter to you personally.

Index would point out that “the proposal is unlawful on the grounds and is disproportionate to its purpose”.

Yours,

Jodie Ginsberg

CEO, Index on Censorship

IN THE MATTER OF A PROPOSED PSPO IN EALING[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Apr 18 | Awards, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/fW_rl97IupM”][vc_column_text]MuckRock is a non-profit, collaborative news site used by journalists, activists and members of the public to request, receive and share government documents from any agency that is subject to transparency laws in the United States. Their aim is to make policies more open to the public, and democracies further informed.

“MuckRock has continued to double in size each year,” said MuckRock. “We hope to continue increasing our impact, putting cutting edge transparency tools in the hands of journalists, whistleblowers, researchers and ordinary people to have impact at the national, international, and local levels.”

The site, which has a user base of 10,000, hosts an archive filled with hundreds of thousands of pages of original government materials, as well as information about how to file requests, and tools to make the requesting process easier. MuckRock has filed over 40, 000 requests, shedding light on government surveillance, censorship and police militarisation among hundreds of other issues. The site’s staff and contributors use the documents received through the site to create original investigative reporting and analysis.

MuckRock filed and won a lawsuit against the CIA, which resulted in the release of 13 million pages of previously secret documents from the CREST Database – the CIA’s database of declassified information dating back through the Cold War. The foundation also fought off a lawsuit from multinationals seeking to hide security flaws in their smart metering technology.

Their work investigating the US government’s 1033 programme, which supplied local police and the private prison system with military equipment, helped lead to major reforms of these policies.

Stories that MuckRock have reported on over the past year include: gaps in gun violence data, surveillance footage from the top of the Smithsonian building on inauguration day – contributing to the debate of the true crowd size, and classified CIA documents that were left stashed in the Rockefellers barn.

After he had been in office for over a year, MuckRock investigated the effects of president Trump’s harsher immigration policies, and found that the number of deportations was actually decreasing, while the number of people held in detention centres was rising.

The site has had a particularly successful 2017, seeing its 10,000th public records request successfully completed. They also celebrated International Right To Know day by expanding their reach to Canada, which is ranked a lowly 49th out of 111 countries on the RTI Rating.

The site has also focused on expanding its education about requesting documents, and produced a Freedom of Information Act 4 Kidz lesson plan to help educators to start discussions about government transparency.

“It’s impossible to quantify the impact of this acknowledgement of our amazing transparency community,” said MuckRock. “This nomination recognizes the important work of all the MuckRock users who have fought to open up government on so many issues, often facing bureaucratic hurdles and legal threats to create a strong civic society for all.”

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460×490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1523523704690-32d26e8d-1852-3″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Apr 18 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]By Ciaran Willis, Lauren Brown and Samantha Chambers

Zainab and Maryam al-Khawaja

The daughters of Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, the co-founder of Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, participated in a demonstration on Monday 9 April outside the Bahrain Embassy in London calling for his release on the seventh anniversary of his arrest.

Maryam and Zainab al-Khawaja joined NGOs and fellow supporters, as they chanted “free free Abdulhadi” and held placards with a picture of the Bahraini human rights activist.

It marked seven years since Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, founder of the 2012 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, was imprisoned for his involvement in peaceful pro-democracy protests that swept the country during the Arab Spring. On 9 April 2011 twenty masked men broke into his house, dragged him down the stairs and arrested him in front of his family.

Bahrain has a poor track record on human rights, with many reports of torture and human rights defenders in jail. Al- Khawaja was part of the Bahrain 13, a group of journalists and activists who faced unfair trials following the unrest.

During his time in prison, Al-Khawaja has been tortured, sexually abused and admitted to hospital requiring surgery on a broken jaw.

His daughter Maryam al-Khawaja was imprisoned in Bahrain for a year before leaving the country in 2014. She faces prosecution on charges including insulting the king and defamation. She told Index: “For me, this isn’t just about my dad, it’s a reminder that we have thousands of prisoners in Bahrain, and we need to remember all of them, and we need to be fighting on behalf of all of them. These are all prisoners of conscience.”

A number of prominent Bahraini campaigners took part in the demonstration.

Jawad Fairooz, a former Bahrain MP and president of SALAM for Democracy and Human Rights, said: “We’re here to support Abdulhadi as a symbol of the demand of the people of Bahrain who want to live in the country with dignity and freedom.”

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy and an activist who fled the country following torture, said: “I’m proud to belong to a nation that Abdulhadi is a part of. Abdulhadi to me is one of the most inspirational individuals.”

Cat Lucas, programme manager at English Pen’s Writers at Risk initiative, said that the government could be doing a lot more to challenge what is going on in Bahrain. She hopes the Bahraini Embassy will finally act, not just in the case of al-Khawaja, “but in the case of lots of writers and activists who are imprisoned for their peaceful human rights activities”.

Protesters have gathered outside the Embassy once a month since January 2018 to highlight the dire human rights situation and ask the UK government to take action.

Al- Khawaja’s daughter Zainab called on the UK to hold the Bahraini regime accountable: “Major governments are still supporting the Bahraini regime with weapons and political training. They’re the people behind them. I can feel as angry here as I would protesting in Bahrain, because I know what the government here is responsible for. I know one of the reasons people are being killed and tortured in Bahrain, including my father, is the support from the British and American governments.”

A group of NGOs, including Index on Censorship and Pen International, signed a letter last week calling on Bahrain to cease its abuse of fundamental human rights.They asked the authorities to immediately and unconditionally free Abdulhadi, provide proper access to medical care and allow international NGOs and journalists access to Bahrain.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8lkS7Fsyqso”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1523361455279-ef10ef07-647f-1″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Apr 18 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, Uncategorized

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In 2011 Bahraini human rights defenders were arrested for pro-democratic activism. Seven years on, monthly protests are reminders of ongoing injustice.

Protesters gathered outside the Bahrain Embassy shouting “free free Abdulhadi” as activists continue to be targeted

NGO’s gathered yesterday at the Bahrain embassy in London to call for the release of Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, a human rights defender imprisoned for life seven years ago for organising peaceful protests against Bahrain’s government during the country’s Arab Spring uprising.

Al-Khawaja founded the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights in 2002 and is a founding director of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights, established in 2011. He was one of 13 human rights defenders to be arrested during the 2011 demonstrations.

Index on Censorship and other human rights organisations have called for his immediate release and for all human rights defenders jailed in Bahrain to be freed.

Monday’s protest not only signalled the ongoing persecution of al-Khawaja, but with repeated calls for his release, highlight Bahrain’s systematic imprisonment and targeting of human rights activists since the Arab Spring.

Front Line Defenders recently reported that all human rights defenders in Bahrain have been exiled, imprisoned or prevented from freely working or travelling. Here, we profile some of those targeted:

Nabeel Rajab

This human rights defender was imprisoned for five years in February 2018 for tweets and retweets perceived as inflammatory by the Bahraini authorities. The posts, from 2015, relate to torture in Bahrain’s Jau prison and the killing of civilians. He has been in and out of prison for peaceful human rights activism since 2012, with charges ranging from “incitement to non-compliance with the law” and “spreading false news” to “incitement to hatred against the regime”.

Nedal Al-Salman

Head of women and children’s rights advocacy for the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, Al-Salman was stopped at Bahrain International Airport in December 2017. She was prevented from travelling and has since been banned from leaving the country. The same happened in 2016 when she was barred from exiting on her way to attend the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva. In April 2017 Sharaf Al-Mousawi was also stopped on her way to a development meeting in Lebanon.

Ebtisam Al-Saegh

Al-Saegh, who works for Salam for Human Rights and Democracy, was one of 22 human rights defenders who were interrogated by the Bahraini authorities in April 2017. They had all supposedly attended an illegal meeting. Most were informed they were banned from travelling. Al-Saegh has been repeatedly targeted by the authorities, sexually assaulted and threatened with rape for her human rights advocacy.

Saeed Al-Samahiji

Saeed Al-Samahiji, an opthamologist, used his medical expertise to help protesters injured in the 2011 Bahraini Arab Spring. In 2012 he was sentenced to 10 years in prison for his involvement but was released in 2013 following an appeal. He has since been repeatedly targeted, serving a year in prison in 2014 for insulting the king and being charged for tweets written in 2016. Charges included “threatening a neighbouring country (Saudi Arabia) for the purpose of threatening national security” and “publicly calling for participation in unlicensed demonstrations and marches”.

Duaa Alwadaei

In March 2018 London-based Duaa Alwadaei was sentenced to two months in jail for insulting a police officer. Her trial was conducted without her present. The charge came after Alwadaei told of her mistreatment by security at Bahrain International airport in 2016. Her husband is Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of the UK-based Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy. He attended Monday’s protests at the Bahraini Embassy in London, calling for an end to the persecution of the country’s human rights defenders. [/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8lkS7Fsyqso&feature=youtu.be” align=”center”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1523361407755-9197b56c-e77e-6″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Apr 18 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”99469″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Since Turkey launched a military operation in Afrin, northern Syria, in January, state repression against critical voices has escalated once more. Hundreds of Turkish citizens who expressed their opposition to war, massacres and the displacement of Kurdish civilians have been arrested.

As with two years ago, when a petition by academics against the ongoing war in the Kurdish region was released, demanding peace has been deemed as supporting terror by the government and the pro-governmental media.

On 26 February 2018 a statement from the Ministry of Interior confirmed that 845 people were detained for criticising Turkey’s Afrin operation — code-named Operation Olive Branch — on social media and taking part in protests. Each week now brings new arrests on similar grounds, with students and academics caught up in the wave of repression.

In early February two academics, Onur Hamzaoğlu and Serdar Başçetin, were arrested. Hamzaoğlu is a doctor well known for his research into the correlation between industrial pollution and cancer in Kocaeli Province. He was dismissed from Kocaeli University, along with other signatories of the petition, by an emergency-decree after the attempted coup in July 2016. Hamzaoğlu is a co-founder of the Kocaeli Solidarity Academy and a co-spokesperson of the People’s Democratic Congress (HDK), a union left-wing parties and civil society organisations, formed in 2011 with the aim of recreating politics and promoting a democratic society against social, ethnic, religious and gender discrimination. He was arrested on 9 February before the HDP Congress and is still detained, together with dozens of party members.

Serdar Başçetin was a research assistant who was fired from Erzincan University by emergency decree. He was arrested in Antalya on 13 February for his support to Nuriye Gülmen and Semih Özakça during their hunger strikes and his posts on Afrin on social media. On 29 March he was acquitted of all charges at the first hearing.

Students at Boğaziçi University, one of the leading higher education institutions in the country, known for its autonomy and liberal traditions, have also come under attack. The so-called “Afrin delight” incident started on 19 March when pro-governmental students opened a stand on campus to distribute Turkish delights in honour of the Afrin expedition and the Turkish soldiers who lost their lives there. Tension raised when students carrying a banner reading “No delight for occupation and massacre” protested against the stand and both groups started to fight. What could have remained an incident indicative of the political tensions that exist between students turned into a pretext for a wide police operation on campus. Arrests began on 22 March when five students were rounded-up in the early morning in the dormitories and homes. A press statement organised on the North Campus condemning these arrests gave way to a violent police intervention and further arrests.

In the days that followed president Erdogan himself condemned the “no delight” students, calling them terrorists and adding that these “communists” and “traitors” would not be given right to education. Academics were warned by the president that there would be consequences if they co-operated with these students.

Some students reported being kept for long hours in a police van, severely beaten, insulted and, for some of them, sexually assaulted before being released. Since then, police have been patrolling the campus, leading to fresh arrests. Some of those arrested weren’t even involved in the initial incident. On 3 April, when 15 Boğaziçi students were brought before Çağlayan courthouse, ten were sentenced to pre-trial detention. For their anti-war slogans, they were accused of spreading terrorist propaganda. They remain in prison.

This repression came as no surprise. On 7 January, while speaking at the university on the invitation of a conservative alumni association, Erdogan had criticised the university in the presence of the rector for not being “local and national” enough. Yet Boğaziçi’s loss of autonomy had actually started much earlier. In November 2016, showing no consideration for the summer elections that had seen the previous rector re-elected with more than 80% of votes, Erdogan appointed professor Mehmed Özkan, a Boğaziçi academic who hadn’t even been a candidate in the election. Despite protests by a small group of academics and students, Özkan’s election was greeted with relief by the majority of academics, trusting his promise to protect the liberal tradition of the university and its academic staff. Academic freedom and freedom of expression have come under joint attack from the government and the university administration.

In March 2017 I was dismissed from Boğaziçi, along with professor Abbas Vali, for signing the petition for peace. The Higher Education Council revoked our work permit and the university cancelled our contracts. We were singled out as the two foreign signatories of the petition. Before us, Murat Sevinç, an academic dismissed by emergency-decree from Ankara University, had already been compelled to stop his part-time teaching at Boğaziçi. The rector’s justification for our dismissal was the duty to obey orders – the universal excuse of civil servants trying to escape their responsibilities – and the need to protect the institution against further attacks. Fortunately, this view was challenged by some supportive colleagues and an extraordinary mobilisation of students from the history department who set up a tent throughout the Spring term on the North Campus, where they attempted to raise awareness of our dismissal by inviting academics to participate in outdoor lectures and workshops.

Yet it was already clear by then that the attacks against critical academics across the country and the appointment of a pro-governmental rector had dramatically shrunk the space for critique and opposition on campus. As with elsewhere in Turkey, fear of repression and a disillusionment with the possibility for change grew, and with it, self-censorship spread among academics and students.

Since then, things have only worsened for critical academics and students across the country. In October 2017 the Ministry of Justice made public that more than 36,000 students were detained in Turkey, raising to nearly 70,000 when open university students are included. While the number of students currently detained is likely to be even higher, these figures reflect the heavy price paid by critical students, deprived of their liberty and their right to education for expressing their opposition to state policy. Meanwhile, the trial against the Academics for Peace is ongoing in Istanbul and several academics have already been sentenced to a 15-months suspended prison sentence for spreading terrorist propaganda because they signed the 2016 petition. On 4 April, professır Füsun Üstel, from Galatasaray University, another academic was given a 15-month prison sentence, with the right to appeal the decision.

Aside from the purges, the state authorities encourage a culture of denunciation through dedicated online platforms, where complaints can lead to a police or administrative investigation. The Education Council relentlessly fights against the remaining spaces of academic freedom, relying on the active complicity of most universities’ administrative boards. Both academics’ right to critique and students’ right to education are under threat. After the Boğaziçi incident, the Higher Education Council announced that they considered adopting new disciplinary procedures against students. The same day, in a statement published on Boğaziçi University website, the rectorate denounced terror, welcomed police intervention on campus and announced disciplinary procedure for students who protested against the Afrin expedition, cynically referring to the university’s commitment to “freedom of expression” of the other camp.

While an international petition now calls for solidarity with Boğaziçi students, academics and students must find ways to stand together for a free and diverse university, despite the threats, arrests and intimidation.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1523355691217-4bb55336-d4a1-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Apr 18 | Index in the Press

NCAC joins PEN America and 31 other prominent arts organizations to jointly file a friend of the court brief in the case of State of Hawaii v. Trump, urging the Supreme Court to strike down the third version of the Trump travel ban issued on September 27, 2017. Executive Order (EO) 13780bans all immigration from six majority Muslim countries, placing additional visa restrictions on nationals of Syria, Iran, Libya, Yemen, and Chad, and includes token restrictions on North Korea and Venezuela. Read the full article.

10 Apr 18 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.01 Spring 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Authoritarian leaders know their history. They also know the history they would like you to know. They are aware, perhaps more than anyone else, that choosing images and stories from the past to align and amplify the ways a country is run can be a terribly powerful tool.

As Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan discussed with Index for this issue, dictators have been aware of the power of history to make their arguments for centuries. From the first Chinese emperors to today’s leaders – China’s Xi Jinping and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, among others – the selection of historical stories which reflect their view of the world is revealing.

“The thing about history is if people know only one version then it seems to validate the people in power,” said MacMillan.

But if you know more, you can use that information to make informed decisions about what worked in the past – and what didn’t – allowing people to learn and move on.

And right now, historical validation is an active part of the political playbook. In Russia, Vladimir Putin is a big fan of the tale of the great and powerful Russia. And what he doesn’t like are people who don’t sign up to his version of history.

Even asking questions about the past can provoke anger at the top. It interferes with the control, you see.

In 2014, Dozhd TV had an audience poll about whether Leningrad should have surrendered to the Nazis during World War II. Immediately there were complaints, as Index reported at the time. The station changed the wording of the question almost immediately, but within months various cable and satellite companies had dropped Dozhd from their schedules. Question and you shall be pushed out into the cold.

From the start, this magazine has covered how different countries have attempted to control the historical knowledge their citizens receive by limiting the pipeline (rewriting textbooks or taking history off the syllabus completely, for instance); using social pressure to make certain views taboo; and, in extreme cases, locking up historians or making them too afraid to teach the facts.

In our Winter 2015 issue, we covered the story of a Palestinian teacher who took his students to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland because he felt they should know about the Holocaust. But not everyone agreed. While he was on the trip, there were demonstrations against him, his office was stormed and his car was torched. Later there were threats against his family. To escape the danger, he and his family had to move abroad. The teacher, Mohammed Dajani Daoudi, who wrote about his experiences for the magazine, said: “My duty as a teacher is to teach – to open new horizons for my students, to guide them out of the cave of misconceptions and see the facts, to break walls of silence, to demolish fences of taboos.”

What an incredibly brave vision for a teacher to have in the face of a mob of people who would seek to damage his life, and that of his family, to show how much they disapproved of what he was trying to do.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”But censoring history is not the only way to go about establishing inaccuracies and ill-informed attitudes about the past. Another option is to spin it.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Dajani Daoudi is not alone in fighting against the odds to bring research, open thinking and a wide base of knowledge to students. But, as our Spring 2018 issue shows, the odds are starting to stack up against people like him in an increasing number of places.

In 2010, Maureen Freely wrote a piece called Secret Histories for this magazine, about Turkish laws that had kept most of its citizens in the dark about the killings of a million Armenians in the last years of the Ottoman empire, and how those laws were enforced by making certain things – including criticising the legacy of modern Turkey’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – illegal.

Turkey’s government today has just passed a law making mention of the word “genocide” an offence in parliament, as our Turkish correspondent, Kaya Genç, reports on page 22.

But censoring history is not the only way to go about establishing inaccuracies and ill-informed attitudes about the past. Another option is to spin it.

Resisting Ill Democracies in Europe, the excellent report from the Human Rights House Network, acknowledges that a common thread in countries where democracy is weakening is the “reshaping of the historical narrative taught in schools”. In Poland, the introduction of a Holocaust law means possible imprisonment for anyone who suggests Polish involvement in the Holocaust or that the concentration camps were Polish. In Hungary, the rhetoric of the ruling party is to water down involvement of its citizens in the Holocaust and to rehabilitate the reputation of former head of state Miklós Horthy.

At the same time as undermining public trust in the media, governments in this spin cycle seek to stigmatise academics, as well as close down places where open or vigorous debate might take place. The result is often the creation of a “them and us” mentality, where belief in the avowed historical take is a choice of being patriotic or not.

As the HRHN report suggests, “space for critical thinking, independent research and reporting and access to objective and accurate information are pre-requisites for informed participation in pluralistic and diverse societies” and to “debunk myths”.

However, if your objective is not having your myths debunked then closing down discussions and discrediting opposition voices is the ideal way to make sure the maximum number of people believe the stories you are telling.

That’s why historians, like journalists, are often on the sharp end of a populist leader’s attack. Creating a nostalgia for a time where supposedly the garden was rosy and citizens were happy beyond belief often forms another part of the political playbook, alongside creating a false history.

Another tactic is to foster a sense that the present is difficult and dangerous because of change and because of threats to “traditional” values; and a sense that history shows a country as greater than it is today. The next step is to find a handy enemy (migrants and LGBT people are often targets) to blame for that change and to stoke up anger.

Access to the past matters. Knowledge of what happened, the ability to question the version you are receiving, and probing and prodding at the whys and wherefores are essentials in keeping society and the powerful on their toes.

In this issue of Index on Censorship magazine, we carry a special report about how history is being abused. It includes interviews with some of the world’s leading historians – Lucy Worsley, Margaret MacMillan, Charles van Onselen, Neil Oliver and Ed Keazor (p31).

We look at how history is being reintroduced into schools in Colombia (p60) and how efforts continue to recognise the victims of General Franco’s dictatorship in Spain (p72). We also ask Hannah Leung and Matthew Hernon to talk to young people in China and Japan to discover what they learned at school about the contentious Nanjing massacre. Find out what happened on page 38.

Omar Mohammed, aka Mosul Eye, writes on page 47 about his mission to retain information about Iraq’s history, despite risk to his life, while Isis set out to destroy historical icons.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on The Abuse of History.

Index on Censorship’s spring 2018 issue, The Abuse of History, focuses on how history is being manipulated or censored by governments and other powers.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89164″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229108535157″][vc_custom_heading text=”Brave new words” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229108535157|||”][vc_column_text]2010

In 2010, Maureen Freely wrote a piece called Secret Histories for this magazine, about Turkish laws that had kept most of its citizens in the dark about the killings of a million Armenians in the last years of the Ottoman empire[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90649″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220008536796″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censorship in China” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013495334|||”][vc_column_text]September 2000

How China attempts to censor, using different methods[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229308535477″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taboos” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013513103|||”][vc_column_text]Winter 2015

We tell the story of a Palestinian teacher who took his students to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland because he felt they should know about the Holocaust. But not everyone agreed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The abuse of history” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2018%2F04%2Fthe-abuse-of-history%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends

With: Simon Callow, David Anderson, Omar Mohammed [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2018/04/the-abuse-of-history/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Apr 18 | Awards, Fellowship 2018, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/jPOdNm8Sxos”][vc_column_text]Avispa Midia is an independent online magazine that prides itself on its daring use of multimedia techniques to bring alive the political, economic and social world that is Mexico and Latin America.

“As with avispas (wasps), insects that exist across the world that are equipped with various eyes or ocelli capable of distinguishing between light and dark, Avispa Media seeks to participate in and witness the variety of shades that colour reality,” said Avispa Midia. “We believe that modern-day communication should be nourished by the varied formats and technology that characterise new virtual journalism, such as integrating multimedia tools that make information more dynamic. What sets us apart is our critical, far-reaching eye, primarily through reportage and investigative journalism.”

In the Spanish version, the site’s use of pictures, videos, music and maps to illustrate its stories is particularly striking.

But the beauty of the design masks the serious intent of this collective of journalists and researchers who are seeking to challenge violence and corruption in the region and reflect the lives of marginalised and indigenous people.

They specialise in investigations into organised criminal gangs and the paramilitaries behind mining mega-projects, hydroelectric dams, and the wind and oil industry.

The Latin American world they report on is extremely violent. Between 2000 and 2016, at least 105 journalists were murdered in Mexico for carrying out their work. According to Reporters Without Borders, in 2016 Mexico became third highest country in the world for journalist killings — the most deadly outside war zones.

Avispa Midia says its work has meant that human rights organisations and NGOs have taken action on slave labour and undocumented migrants as a result of their reports.

The site however suffers from scant resources and their main challenge is to be able to establish some form of continuous financing, since they do not have a fixed budget to do their work and no one receives a salary.

Topics that Avispa Midia has addressed in the last year include: US interference in Mexico and Central America; the persecution of peasants in Honduras; land restitution demands by displaced people in Guatemala and the first visit of Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto to the city of Oaxaca.

Many of the reports in the last 12 months have been focused on Mexico and Central America, where the media group has helped indigenous and marginalised communities report on their own stories by helping them learn to do audio and video editing.

In the future the journalists want to create a multimedia journalism school for indigenous people and young people from marginalised neighbourhoods, so that ordinary citizens can inform the world what is happening in their region, and break the stranglehold of the state and large corporations on the media.

“In a field where war has contaminated even communication, where truths but also actions are disputed, having been nominated for the Index of Censorship award lifts our courage up,” said Avispa Midia. “And it enables us to reaffirm our investment in the truth and the tenacity of the voices and experiences we carry through each word and each image documented by Avispa Midia. For us, this represents respect and appreciation for the work we have done. This means expanding the support of communities, civil organisations and academic groups that supported us against the violence exerted against journalists in Mexico.”

See the full shortlist for Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards 2018 here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1521479845471{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-awards-fellows-1460×490-2_revised.jpg?id=90090) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1523523668709-d546d4ac-7872-3″ taxonomies=”10735″][/vc_column][/vc_row]