10 May 17 | About Index

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The International Bill of Human Rights, consisting of the five core human rights treaties of the United Nations that function to advance the fundamental freedoms and to protect the basic human rights of all people, was entered into force in 1967 by the UN General Assembly.

The documents contained in the International Bill of Human Rights are: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; and the Second Optional Procotol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty

The full declaration sets out the basic rights all people should enjoy and expect from their governments and other governments. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights deal directly with freedom of expression.

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

Every citizen shall have the right and the opportunity, without any of the distinctions mentioned in article 2 and without unreasonable restrictions:

(a) To take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives;

(b) To vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the electors;

c) To have access, on general terms of equality, to public service in his country.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship’s summer magazine 2016

We’ll send you our weekly emails and periodic updates on our events. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.

You’ll also get access to an exclusive collection of articles from our landmark 250th issue of Index on Censorship magazine exploring journalists under fire and under pressure. Your downloadable PDF will include reports from Lindsey Hilsum, Laura Silvia Battaglia and Hazza Al-Adnan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”More information about freedom of expression”][vc_column_text]Why is free speech important? Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right. It reinforces all other human rights, allowing society to develop and progress. The ability to express our opinion and speak freely is essential to bring about change in society.

Why is access to freedom of expression important? All over the world today, both in developing and developed states, liberal democracies and less free societies, there are groups who struggle to gain full access to freedom of expression for a wide range of reasons including poverty, discrimination and cultural pressures. While attention is often, rightly, focused on the damaging impact discrimination or poverty can have on people’s lives, the impact such problems have on free expression is less rarely addres[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ order=”ASC” grid_id=”vc_gid:1494247299440-5e8d8e06-86b1-1″ taxonomies=”9210″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

08 May 17 | Media Freedom, News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

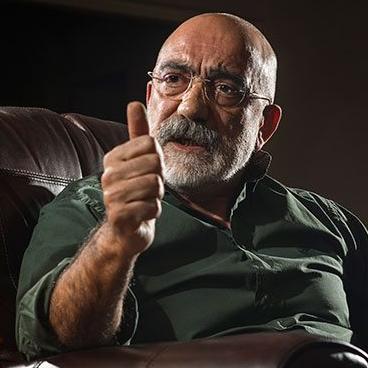

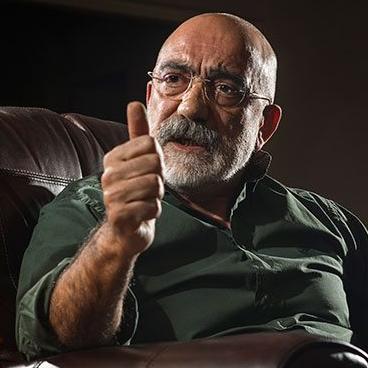

Journalist Ahmet Altan is charged with inserting subliminal messages in support of the failed 15 July coup in Turkey.

Nine months. That’s how long brothers Ahmet and Mehmet Altan have been in pre-trail detention in Turkey. Prosecutors are demanding multiple life sentences for the brothers, who will face their first day in court on 19 June.

“The case against Ahmet and Mehmet Altan is deeply troubling. The ongoing judicial harassment of the Altans and other journalists puts ‘democratic’ Turkey in the same camp as some of the world’s most egregious dictatorships. The post-coup crackdown on freedom of expression and the press must be rolled back,” Melody Patry, head of advocacy, Index on Censorship said.

Ahmet Altan has written for several of the country’s most influential newspapers. He and his brother Mehmet, an academic, were arrested and are being held on suspicion of “spreading subliminal messages”, relating to an appearance Ahmet Altan made on a television talk show the night before the 15 July coup attempt.

Ahmet Altan is one of Turkey’s top journalists, having worked in every position from reporter to editor-in-chief at several newspapers, as well as a producer of television news. He was a columnist for daily newspapers including Hurriyet and Milliyet, and in 2007 he started Taraf, an opposition daily. In 2008 he was charged with “denigrating Turkishness” after he wrote an article dedicated to the victims of the Armenian genocide. He is also considered one of Turkey’s finest novelists, with his most recent book, Endgame, having been published last year.

Mehmet Altan is a professor at Istanbul university, where he has worked for 30 years. A vocal supporter of democracy, he has often called for Turkey to establish its republic on human rights, rather than religious or ethnic identity. He has written several books about politics in Turkey.

The pair were arrested in an early morning raid on 10 September. Ahmet had appeared on a talk show on the Can Erzincan television channel on 14 July, where he is accused of sending messages to viewers to support a coup. The channel has since been shut down. It was perceived by authorities to have been supportive of the cleric Fethullah Gulen, who the government blames for the coup.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

TAKE ACTION

Send a letter of support to Ahmet and Mehmet Altan.

Show your solidarity with the Altans by letting them know the world is watching their case.

Tweet Turkey’s president:

[socialpug_tweet tweet=”.@RT_Erdogan Turkey must end crackdown on #mediafreedom #FreeTurkeyMedia #journalismisnotacrime #AhmetAltan #MehmetAltan” style=”2″ remove_url=”yes” remove_username=”yes”][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1494246747427-afb47fc0-82c9-2″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

08 May 17 | About Index

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A drawing by French cartoonist t0ad

Adopted and proclaimed on 10 December 1948 by the General Assembly of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights contains 30 articles that have been embedded in international treaties, national constitutions and other laws. The declaration is one of the cornerstones of the International Bill of Human Rights, which became law in 1976.

The full declaration sets out the basic rights all people should enjoy and expect from their governments and other governments. Though the declaration is often ignored, it represents the ideal that the world’s government should strive to meet.

Article 18 and Article 19 deal with freedom of thought and freedom of expression most directly, though other articles also reference these fundamental rights.

Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe to the Index newsletters” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that defends people’s freedom to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution. We fight censorship around the world.

To find out more about Index on Censorship and our work protecting free expression, join our mailing list to receive our weekly newsletter, monthly events email and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns. See a sample of what you can expect here.

Index on Censorship will not share, sell or transfer your personal information with third parties. You may may unsubscribe at any time. To learn more about how we process your personal information, read our privacy policy.

You will receive an email asking you to confirm your subscription to the weekly newsletter, monthly events roundup and periodic updates about our projects and campaigns.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”More information about freedom of expression” font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:26|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Why is free speech important? Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right. It reinforces all other human rights, allowing society to develop and progress. The ability to express our opinion and speak freely is essential to bring about change in society.

Why is access to freedom of expression important? All over the world today, both in developing and developed states, liberal democracies and less free societies, there are groups who struggle to gain full access to freedom of expression for a wide range of reasons including poverty, discrimination and cultural pressures. While attention is often, rightly, focused on the damaging impact discrimination or poverty can have on people’s lives, the impact such problems have on free expression is less rarely addressed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

08 May 17 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Youth Board

Each youth advisory board sits for six months, has the chance to participate in monthly video conferencing discussions about current freedom of expression issues from around the world and the opportunity to write blog posts on Index’s website.

The next youth board is currently being recruited. The next youth advisory board will sit from January to June 2018.

We are looking for enthusiastic young people, aged between 16-25, who must be committed to taking part in monthly meetings, which are held online with fellow participants. Applicants can be based anywhere in the world. We are looking for people who are communicative and who will be in regular touch with Index.

Applications include:

- Cover letter

- CV

- 250-word blog post about any free speech issue

Applications can be submitted to Danyaal Yasin at [email protected]. The deadline for applications is 10 January at 11:59pm GMT.

What is the youth advisory board?

The youth board is a specially selected group of young people aged 16-25 who will advise and inform Index on Censorship’s work, support our ambition to fight for free expression around the world and ensure our engagement with issues with tomorrow’s leaders.

Why does Index have a youth board?

Index on Censorship is committed to fighting censorship not only now, but also in future generations, and we want to ensure that the realities and challenges experienced by young people in today’s world are properly reflected in our work.

Index is also aware that there are many who would like to commit some or all of their professional lives to fighting for human rights and the youth board is our way of supporting the broadest range of young people to develop their voice, find paths to freely expressing it and potential future employment in the human rights, media and arts sectors.

What does the youth board do?

Board members meet once a month via Zoom to discuss the most pressing freedom of expression issues. During the meeting members will be given a monthly task to complete. There are also opportunities to get involved with events such as debates and workshops for our work with young people as well as our annual Freedom of Expression Awards and Index magazine launches.

How do people get on the youth board?

Each youth board will sit for a six-month term. Current board members are invited to reapply up to one time. The board will be selected by Index on Censorship in an open and transparent manner and in accordance with our commitment to promoting diversity. We usually recruit for board members during May and December each year. Follow @IndexCensorship on Twitter or subscribe to our Facebook feed to watch for the announcements.

Why join the Index on Censorship youth advisory board?

You will be associated with a media and human rights organisation and have the opportunity to discuss issues you feel strongly about with Index and peers from around the world. At each board meeting, we will also give you the chance to speak to someone senior within Index or the media/human rights/arts sectors, helping you to develop your knowledge and extend your personal networks. You’ll also be featured on our website.

04 May 17 | Art and the Law Case Studies, Artistic Freedom Case Studies

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”90233″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]About Positive Hell

Positive Hell is a 30-minute documentary that tells the stories of five Spanish people, living in northern Spain, who tested positive for HIV in the late 80s who, defying the overwhelming medical consensus, chose not to take medication, or took it for a short period of time and then stopped. Although one of the protagonists dies before the film is finished, he had lived for 27 years without HIV medication, and his testimony alongside the others maintains that their decision was life-enhancing and not life-threatening. The premise of the film is that the widely-accepted scientific approach to prognosis, diagnosis and treatment is wrong and that the drug companies “are the only beneficiaries” to the current approach to AIDS treatment.

The film – written and narrated by Joan Shenton of Meditel Productions was co-produced with the film’s director Andi Reiss of Yellow Entertainment – has been screened at many festivals around the world and was nominated for best film at the Marbella Film Festival.

In 2016, two planned London screenings of the film were pulled – by the London Independent Film Festival (LIFF) and the Portobello Film Festival (PFF). A third screening was pulled by Bluestockings Bookstore in New York and so outside the UK scope of Index on Censorship’s Art and Offence programme. In all three cases, cancellation of the planned screening came following public pressure and pressure from campaigning groups and science professionals.

The cancellations

The two cancellations in London followed a similar pattern: the film was accepted, programmed and advertised as part of a forthcoming festival programme. Within days of going public, the directors of the film festivals received letters from leading AIDS charities asking the film be pulled. The directors of the film festivals then wrote to the producers of the film, informing them that the film would no longer be part of the festival.

Positive Hell was due to be screened at London Independent Film Festival on 17 April 2016 and was cancelled the previous week. Portobello Film Festival was due to be screened on 12 September 2016 and was cancelled on 8 September.

Shenton contacted Index following the second cancellation of the film, to see if Index could help find out further information about why the films were pulled from the festivals. Index suggested that a Freedom of Information request could be made to Kensington Council, which was one of the funders of the Portobello Film Festival. The response to the FOI request outlined the reasons for cancelling the film, which the director had already conveyed in previous emails to Shenton and which are outlined below.

In researching this case study, Index wrote to the National Aids Trust and Terrence Higgins Trust, the two charities named in correspondence with LIFF (see below), asking them for access to the letters they sent to the festival directors. Index received, by return, a copy of the letter sent to Erich Schultz, director of LIFF, by Deborah Gold, Chief Executive of National Aids Trust.

Gold wrote: “The film proposes that the origin and nature of HIV and AIDS are up for debate and that is simply not true. There is 30 years of worldwide, respected research showing exactly how HIV works in the body and how it is contracted – as well as irrefutable evidence that without medication it will lead to AIDS. …Denying this basic truth about HIV and AIDS kills people.“

She ends: “Giving a platform to people who spread these abhorrent and dangerous views is incredibly irresponsible. I urge you to withdraw the screening of this film as a matter of urgency.“

The Terence Higgins Trust did not reply.

Case study continues below[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1493909985972{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/art-and-the-law-1460×490-2.jpg?id=80212) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index also wrote to both festival directors inviting them to discuss their reasons for pulling the film. Eric Schultz, director of LIFF did not reply. However, Shenton shared email correspondence in which Schultz indicated “two more major HIV/AIDS organisations” had contacted him urging him not to screen the film and “warning of protests to LIFF, the screening venue and the festival’s sponsors” if they failed to comply. Schultz said he had also received over twenty protest letters, including one from a LGBT society at the university where Schultz teaches and where the festival’s student advisory board is based.

The decision by Portobello Film festival to screen the film was condemned in an article by Buzzfeed LGBT editor Patrick Strudwick published on September 7, a day before the cancellation of the film was announced.

The Buzzfeed article brought together a range of voices that support the medical consensus on HIV and AIDS. In the article, Jonathan Barnett – director of the Portobello Film Festival – is quoted as saying: “We believe passionately in freedom of speech and expression, but clearly have no desire to create any distress. However in the spirit of not causing upset and as a people’s festival that is responsive to feedback from the public we have decided to pull the film.”

In reply to our approach, Barnett provided Index with a brief summary about the cancellation by email.

“The Festival has been going for 21 years. We are a free festival. We do not charge for film selection or submission, or entry to any of our events. We pulled the film due to concerns expressed to us and articulated in the attached Buzzfeed article. We invited Ms Shenton to the Festival where she gave a speech and distributed flyers… I hope we were responsible in not screening the film in case of the possible distress it could cause to Aids sufferers. Both Terrance Higgins and NAT, who might fairly be regarded as experts in this field, regard the film as unhelpful.”

Barnett told Index he was unaware of the controversial nature of the film when it was originally chosen for the festival. He stressed that although the festival decided to drop the film he did offer Shenton a chance to speak publicly about it, which she took up.

Barnett said the festival listened to the concerns of AIDS charities. “It is the view of AIDS charities and doctors that HIV/AIDS denial is a movement which has real and deadly repercussions for people living with HIV who then believe that they can stop anti-retrovirals and survive,” he told Index via email. “This also leads to ongoing transmissions fuelling the epidemic. There is overwhelming evidence, in the UK and worldwide, of tragedy that HIV/AIDS denial costs. When this was pointed out to us we pulled the film. No action, protest or otherwise, was threatened.”

Other opposition to the film

In February 2015, the filmmakers privately hired the London Frontline Club (FLC) for an invite-only launch of the film and the self-publishing of an updated copy of Shenton’s book Positively False. Although the Frontline Club was criticised for hosting the screening at their premises in Paddington, London, it went ahead without incident.

On this occasion, the pressure to cancel the event came from science writers Simon Singh and Ben Goldacre. Singh tweeted: “Is FLC smart enough to admit error + cancel? RT @bengoldacre: Shame on you @frontlineclub promoting AID denialism. https://www.pressdispensary.co.uk/releases/c993891/preview.html …”.

Index wrote to Singh asking him why, at the time, he thought that Frontline Club should cancel the film. He gave a detailed response, concluding:

“Clearly, it is not up to me to ban films, and nor would I want such power, but instead I was merely offering information and stressing that I thought they were doing the wrong thing by hosting the film. As a journalist, I think that I was making it clear that my opinion of the Frontline Club would fall if they were to go ahead with a policy of, essentially, taking money to screen any film regardless of the quality or accuracy. And I think many other science and health journalists would have felt the same.”

Shenton argues that by cancelling the film screenings, the five protagonists have been denied their voice and their experience has been invalidated.

“The film describes the agonies of being labelled as ‘HIV positive’ and poses these questions: just how reliable are the regular tests and diagnoses for HIV and how essential is it for everyone found HIV-positive to submit unquestioningly to a possible lifetime regime of antiretroviral drugs. The film’s protagonists made their own decisions not to take the HIV treatments offered and have lived healthy lives for almost three decades.”

A screening of the film was also cancelled at a bookstore in New York in 2016 although the film has been screened at other festivals, including the Queen’s World Film Festival in New York in March 2017 where it was awarded a special jury prize.

For more information about the issues and guidance for screening, displaying and mounting of controversial work and freedom of expression, please see our Art and Offence guidelines.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1494248689291-0c39a0ce-fa9d-5″ taxonomies=”8883″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

04 May 17 | News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

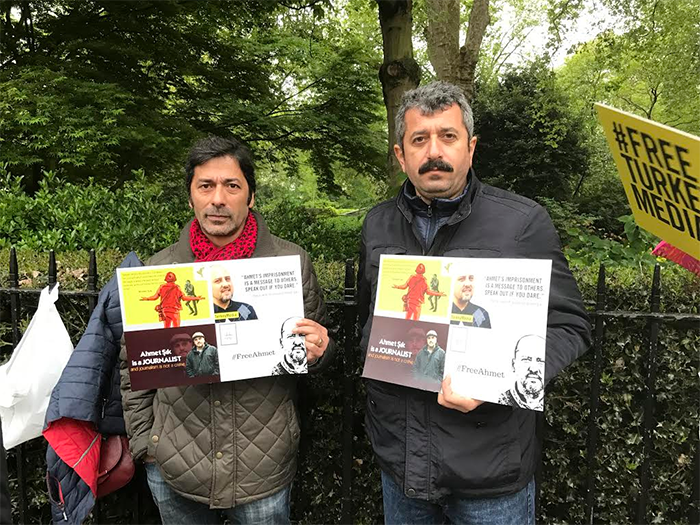

On 3 May, World Press Freedom Day, dozens of activists and journalists gathered outside the Turkish Embassy in London to protest the arrest and imprisonment of journalists in Turkey. Index on Censorship joined Amnesty International, English Pen, Article 19 and others bearing signs and messages of hope.

Following the failed military coup in July of 2016, the Turkish government has unleashed a massive crackdown on its opposition, specifically targeting journalists, media outlets and educators.

Since then, over 150 journalists have been detained and over 170 media outlets have been shut down, resulting in an additional 2,500 journalists being out of work. Turkey is now the number one jailer of journalists in the world.

Seamus Dooley, the acting general secretary of the Nation Union of Journalists, addressed the protest, which took place across the street from the embassy: “We may be on the wrong side of the road but we are on the right side of history.”

Dooley highlighted the importance of coming out to protest in support of Turkey’s journalists, regardless of the weather: “Solidarity is the most important thing we can give them. Although this may seem like a dark time, the fact we are still with them shines a light on it.”

Many protesters stressed the importance of continuing to campaign until those being silenced in Turkey are free.

Ulrike Schmidt, Amnesty International

Ulrike Schmidt of Amnesty International said: “As a human rights organisation it’s our job to speak out. It’s World Press Freedom Day so we’re standing here to support the journalists in Turkey. We will keep campaigning until they can do their work again.”

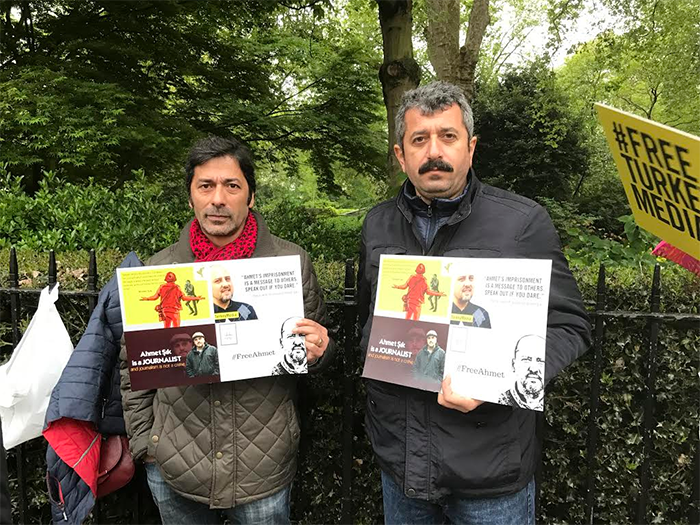

Others spoke out specifically about friends who had been detained as a result of the crackdown. Two of the protesters (pictured below) came specifically to highlight the case of Ahmet Sik, a journalist with the Turkish opposition newspaper Cumhuriyet, who is currently being tried on accusations of spreading terrorist propaganda as well as insulting the state.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493899892143-33f1af52-13d4-5″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

03 May 17 | About Index, Digital Freedom

- Introduction

1.1 We are committed to safeguarding the privacy of visitors to www.indexoncensorship.org; we strive to minimise the amount of information we collect or allow to be collected by third parties on our website; in this policy, we explain how we will treat your personal information.

1.2 We will ask you to consent to our use of cookies in accordance with the terms of this policy when you first visit our website. By using our website and agreeing to this policy, you consent to our use of cookies in accordance with the terms of this policy.

- Collecting personal information

2.1 Where possible we minimise the amount of information we collect by contracting with third parties. For example, event ticketing through Eventbrite (Privacy Policy) or donations processing through PayPal (Privacy Policy)

2.2 We may collect, store and use the following kinds of personal information:

(a) information about your computer and about your visits to and use of this website including your IP address, geographical location, browser type and version, operating system, referral source, length of visit, page views and website navigation paths

(b) Information that you provide to us for the purpose of subscribing to our email notifications and/or newsletter including your name and email address

(f) Information contained in or relating to any communication that you send to us or send through our website including the communication content and metadata associated with the communication

(g) Any other personal information that you choose to send to us; and provide details of other personal information collected.

2.3 Before you disclose to us the personal information of another person, you must obtain that person’s consent to both the disclosure and the processing of that personal information in accordance with this policy.

- Using personal information

3.1 Personal information submitted to us through our website will be used for the purposes specified in this policy. Your information will not be published without your explicit permission.

3.2 We may use your personal information to:

(a) Administer our website and business

(b) Enable your use of the services available on our website

(c) Send you email notifications that you have specifically requested

(d) Send you our email newsletter, if you have requested it; You can inform us at any time if you no longer want to receive the newsletter

(e) Send you marketing communications relating to our business, where you have specifically agreed to this, by email, text or similar technology you can inform us at any time if you no longer require marketing communications

(f) Deal with enquiries and complaints made by you relating to our website

(g) Keep our website secure and prevent fraud

(h) Other uses

3.3 If you submit personal information for publication on our website, we will publish and otherwise use that information in accordance with the licence you grant to us.

3.5 We will not supply your personal information to any third party for the purpose of their or any other third party’s direct marketing.

- Disclosing personal information

4.1 We may disclose your personal information to any of our employees, officers, insurers, professional advisers, agents, suppliers or subcontractors insofar as reasonably necessary for the purposes set out in this policy.

4.3 We may disclose your personal information:

(a) To the extent that we are required to do so by law;

4.4 Except as provided in this policy, we will not provide your personal information to third parties.

- International data transfers

5.1 Information that we collect may be stored and processed in and transferred between any of the countries in which we operate in order to enable us to use the information in accordance with this policy.

5.2 Information that we collect may be transferred to the following countries which do not have data protection laws equivalent to those in force in the European Economic Area: the United States of America

5.3 Personal information that you publish on our website or submit for publication on our website may be available, via the internet, around the world. We cannot prevent the use or misuse of such information by others.

5.4 You expressly agree to the transfers of personal information described in this Section 5.

- Retaining personal information

6.1 This Section 6 sets out our data retention policies and procedure, which are designed to help ensure that we comply with our legal obligations in relation to the retention and deletion of personal information.

6.2 Personal information that we process for any purpose or purposes shall not be kept for longer than is necessary for that purpose or those purposes.

6.3 Notwithstanding the other provisions of this Section 6, we will retain documents (including electronic documents) containing personal data:

(a) To the extent that we are required to do so by law;

(b) If we believe that the documents may be relevant to any ongoing or prospective legal proceedings; and

(c) In order to establish, exercise or defend our legal rights (including providing information to others for the purposes of fraud prevention and reducing credit risk).

- Security of personal information

7.1 We will take reasonable technical and organisational precautions to prevent the loss, misuse or alteration of your personal information.

7.2 We will store all the personal information you provide on our secure password- and firewall-protected servers.

7.3 All electronic financial transactions entered into through our website will be protected by encryption technology.

7.4 You acknowledge that the transmission of information over the internet is inherently insecure, and we cannot guarantee the security of data sent over the internet.

- Amendments

8.1 We may update this policy from time to time by publishing a new version on our website.

8.2 You should check this page occasionally to ensure you are happy with any changes to this policy.

8.3 We may notify you of changes to this policy by email

- Your rights

9.1 You may instruct us to provide you with any personal information we hold about you; provision of such information will be subject to:

(a) The supply of appropriate evidence of your identity for this purpose, we will usually accept a photocopy of your passport certified by a solicitor or bank plus an original copy of a utility bill showing your current address.

9.2 We may withhold personal information that you request to the extent permitted by law.

9.3 You may instruct us at any time not to process your personal information for marketing purposes.

9.4 In practice, you will usually either expressly agree in advance to our use of your personal information for marketing purposes, or we will provide you with an opportunity to opt out of the use of your personal information for marketing purposes.

- Third party websites

10.1 Our website includes hyperlinks to, and details of, third party websites.

10.2 We have no control over, and are not responsible for, the privacy policies and practices of third parties.

- Updating information

11.1 Please let us know if the personal information that we hold about you needs to be corrected or updated.

- About cookies

12.1 A cookie is a file containing an identifier a string of letters and numbers that is sent by a web server to a web browser and is stored by the browser. The identifier is then sent back to the server each time the browser requests a page from the server.

12.2 Cookies may be either “persistent” cookies or “session” cookies: a persistent cookie will be stored by a web browser and will remain valid until its set expiry date, unless deleted by the user before the expiry date; a session cookie, on the other hand, will expire at the end of the user session, when the web browser is closed.

12.3 Cookies do not typically contain any information that personally identifies a user, but personal information that we store about you may be linked to the information stored in and obtained from cookies.

12.4 Cookies can be used by web servers to identify and track users as they navigate different pages on a website and identify users returning to a website.

- Our cookies

13.1 We use both session and persistent cookies on our website.

13.2 The names of the cookies that we use on our website, and the purposes for which they are used, are set out below:

(a) We use cookies on our website to recognise a computer when a user visits the website, track users as they navigate the website, improve the website’s usability, analyse the use of the website, administer the website, prevent fraud and improve the security of the website.

(b) Third parties may track users on our website when they interact with specific site functions such as social media sharing buttons or embedded video.

- Analytics cookies

14.1 We use Google Analytics to analyse the use of our website.

14.2 Our analytics service provider generates statistical and other information about website use by means of cookies.

14.3 The information generated relating to our website is used to create reports about the use of our website.

14.5 Our analytics service provider’s privacy policy is available at: http://www.google.com/policies/privacy.

- Blocking cookies

16.1 Most browsers allow you to refuse to accept cookies; for example:

(a) in Internet Explorer you can block cookies using the cookie handling override settings available by clicking “Tools”, “Internet Options”, “Privacy” and then “Advanced”;

(b) in Firefox you can block all cookies by clicking “Tools”, “Options”, “Privacy”, selecting “Use custom settings for history” from the dropdown menu, and unticking “Accept cookies from sites”; and

(c) in Chrome, you can block all cookies by accessing the “Customise and control” menu, and clicking “Settings”, “Show advanced settings” and “Content settings”, and then selecting “Block sites from setting any data” under the “Cookies” heading.

16.2 Blocking all cookies will have a negative impact upon the usability of many websites.

16.3 If you block cookies, you will not be able to use all the features on our website.

- Deleting cookies

17.1 You can delete cookies already stored on your computer; for example:

(a) In Internet Explorer, you must manually delete cookie files you can find instructions for doing so at http://windows.microsoft.com/engb/internet-explorer/delete-manage-cookies#ie=ie-11;

(b) in Firefox you can delete cookies by clicking “Tools”, “Options” and “Privacy”, then selecting “Use custom settings for history” from the drop-down menu, clicking “Show Cookies”, and then clicking “Remove All Cookies”; and

(c) in Chrome, you can delete all cookies by accessing the “Customise and control” menu, and clicking “Settings”, “Show advanced settings” and “Clear browsing data”, and then selecting “Cookies and other site and plug-in data” before clicking “Clear browsing data”.

17.2 Deleting cookies will have a negative impact on the usability of many websites.

- Our details

18.1 This website is owned and operated by Index on Censorship (Writers & Scholars Education Trust Ltd.)

18.2 Writers & Scholars Educational Trust is a registered charity (number 325003). Our office is located at 292 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, SW1V 1AE. If you have any other questions about this policy you can write to us at our office or email [email protected] or call us on +44 (0) 207 963 7262

03 May 17 | Campaigns -- Featured, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Statements

London, 3 May 2017. On World Press Freedom Day, Reporters Without Borders – known internationally as Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) – English PEN, and Index on Censorship have published their joint submission to the Law Commission’s Consultation on the Protection of Official Data. The free speech and press freedom groups welcome the opportunity to review legislation that is long overdue for reform, following the significant changes in the collection, retention and sharing of data over the past 20 years and the challenges facing both privacy and freedom of expression in the digital age.

London, 3 May 2017. On World Press Freedom Day, Reporters Without Borders – known internationally as Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) – English PEN, and Index on Censorship have published their joint submission to the Law Commission’s Consultation on the Protection of Official Data. The free speech and press freedom groups welcome the opportunity to review legislation that is long overdue for reform, following the significant changes in the collection, retention and sharing of data over the past 20 years and the challenges facing both privacy and freedom of expression in the digital age.

In the joint submission, RSF, English PEN, and Index on Censorship emphasise the importance of ensuring that official secrets legislation is fit for purpose. They argue that any reform must take account of the potential impact on legitimate activities pursued in the public interest, including the activities of investigative journalists and the sources upon whom they rely. They consider that the Law Commission’s provisional conclusions with respect to protection of public interest disclosures are inadequate and reject the proposal for a statutory commissioner as an ineffective mechanism for safeguarding the public interest.

The groups disagree with the Law Commission’s conclusion that the problems associated with the introduction of a statutory public interest defence outweigh the benefits and do not support the view that there are already sufficient existing safeguards for journalists. They submit that there should be no category of protected information created for sensitive economic information.

“The Law Commission’s proposal is nothing short of alarming, particularly when viewed in the context of a broader trend of worrying moves against press freedom in the UK over the past year, resulting in the UK dropping to a ranking of 40th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2017 World Press Freedom Index. The prospect of journalists being labelled as ‘spies’ and facing the threat of serious jail time for simply doing their jobs in the public interest is outrageous. This proposal must be revised with respect for press freedom at its core,” said Rebecca Vincent, UK Bureau Director for RSF.

“This is an important opportunity to reform official secrets legislation and make it fit for the 21st century. Our response to the consultation demonstrates that it is both viable and necessary to include a public interest defence. Some of the most important news stories of the past seven years have been based on leaks of classified information that are squarely in the public interest and have resulted in critical public debate about foreign policy, privacy and freedom of expression. These laws go back to the Edwardian era and it’s vital that we now have legislation for our times,” said Jo Glanville, Director of English PEN.

“It makes sense to update outmoded laws but no sense whatsoever to update them in such a way that they undermine the very liberties and freedoms on which our rule of law is based. The proposals laid out by the Law Commission threaten free expression and in particular a free media in the UK and should not be implemented in their current form,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship.

Notes:

- Reporters Without Borders, English PEN, and Index on Censorship would like to thank barristers Can Yeginsu and Anthony Jones of 4 New Square Chambers, as well as Tom Francis of Joseph Hage Aaronson LLP, for their assistance in preparing this submission.

- Press contact: Rebecca Vincent, [email protected] or +44 (0)7583 137751

03 May 17 | Index in the Press

When satirical blogger Yameen Rasheed was brutally murdered in the stairwell of his apartment block on 23 April, it brought home a regrettable reality for fellow Maldivian journalist Zaheena Rasheed (no relation): Paranoia can be paralysing, but journalists in the Maldives “should never let their guards down”. Read the full article

03 May 17 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

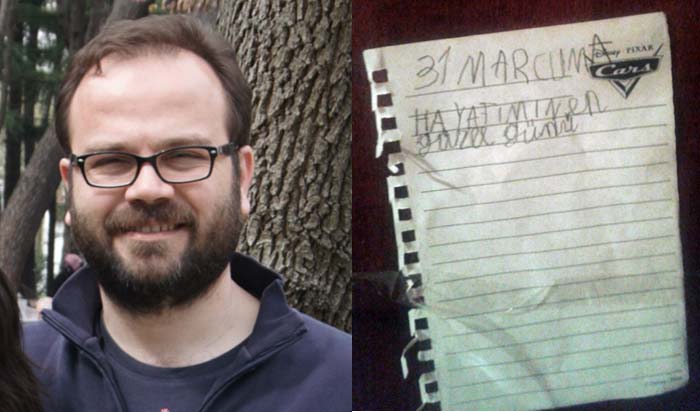

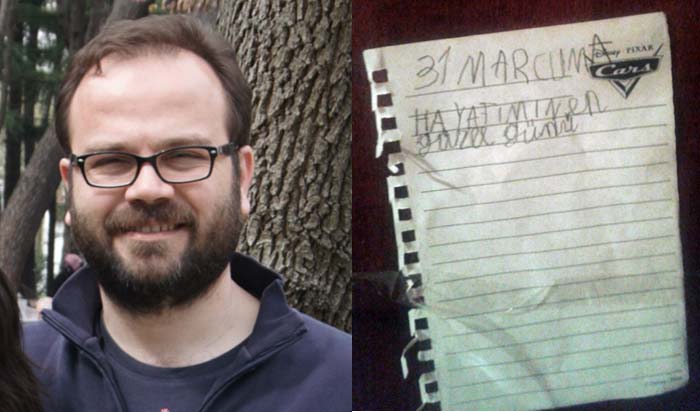

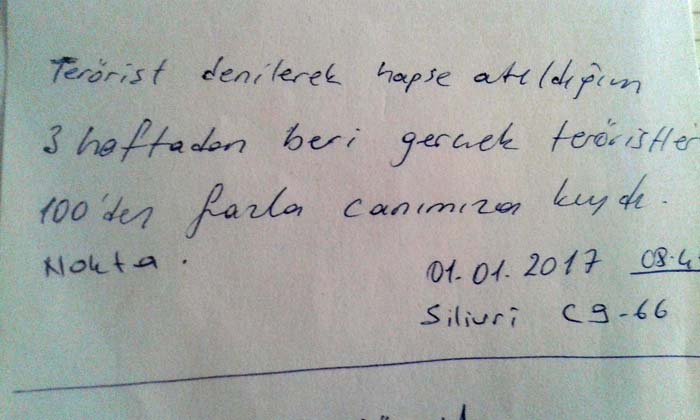

Journalist Oguz Usluer has been accused of being a terrorist. The note, from his six-year-old son, reads: “31 March Friday. The happiest day of my life.”

On 31 March 21 journalists who were charged with working for the media arm of the alleged group behind the 15 July coup attempt were released by a court ruling. Following a tweet from a pro-government troll account, the prosecutor filed an objection to the release of eight and announced that it had launched a new investigation for the other 13.

The judges who issued the release ruling were suspended about a week after the trial.

During the few hours before the new detention warrants came, their families had already driven to Silivri Prison, where they have been held for months. Among them was Sunay Usluer, the wife of a former television coordinator who was arrested in December 2016. She shared with Index on Censorship her account of the anxious hours waiting for the release that never came.

“I am planning to bring the children to the next visit after the trial.”

“But of course there is always the possibility that I might be released in the next session, although you seem not to even consider that.”

Such was the conversation I had with my husband Oğuz on Thursday 23 March, during my last prison visit before the 31 March trial hearing. This entire process had the air of a tragicomical joke; we were laughing when we should have been crying. Although for the past four months, neither of us had given up hope, we didn’t really expect a fair trial or a release ruling from the court. But, at least, we would be able to see each other for five days in a row during the scheduled trial sessions; a rare occurrence.

With this motivation, we started the five-day session marathon. The 25 people, who were on trial for membership in a terrorist organisation and who didn’t know each other in the slightest, were in the front row in the courtroom. Dozens of their family members, living 25 different human stories together with them, sat in the back of the room. Everyone wore the same exhausted expression on their face, reflecting the months fraught with ambiguity and fragile flickers of hope.

While waiting for the trial sessions that never seemed to start, or while waiting during long intervals, people who put their own identities aside and described themselves as the “wife, mother, son/daughter” of a particular journalist, started speaking about the shared-yet-separately-lived agony they have endured, after months of longing for a conversation with someone who can understand them. One of them said, “I can’t tell you how happy I am to see that people who are going through the same tribulations as me still being able to laugh,” while we laughed as we played a game of release-lotto with our lawyer.

Our lawyer has been extremely supportive in this process. He always had hope, but I was the devil’s advocate. “You say he will be released, but I will not believe that until I see him next to me.”

Court officials moved the trial to a smaller courtroom for the final three days. Family members of those on trial were allowed inside only for 15 minutes in whatever room was left unoccupied by journalists and lawyers.

On the morning of the fifth and final day, the prosecutor was reading out a list of those he recommended be released. At that moment, I caught Oğuz’s eye and made a gesture asking if he was on the list. “Yes, but it’s only the prosecutor’s request,” he said, in order to fend off the likely frustration that might follow. Fearing to have hope is worse than despair; something we have found out in this process.

At the end of the fifth day, everyone was too exhausted to even speak. While waiting for the court’s decision, only the sounds of shy seagulls from outside could be heard as if it was sinful to talk in the corridor where the 25th High Criminal Court is located. Then there was the sound of a notification on my phone, and the ticker reading “released” on a television screen. This scene was followed by 21 families, crying tears of happiness, hugging each other. People who still found the news hard to believe, relying on confirmations from each other.

“I couldn’t believe it. I walked towards the courtroom, and I asked a lawyer who I didn’t know at all if my husband is among those released. I suddenly gave him a hug when he answered yes,” somebody said.

Later, our lawyer walked out of the courtroom. His first remark took a jab at my longstanding incredulity. I still had no intention of believing that he really was to be released until he was next to me. I didn’t voice my concern in the way you think you might jinx a good thing if you say something negative. I, carrying this worry in my heart, my ten-year-old son, whom I’d brought with me so that he could at least catch a glimpse of his father, and our relatives celebrated. Oğuz’s family in İzmir were already boarding a plane to Istanbul to celebrate with us. We will most likely have picked him up from prison by the time they arrive, I thought.

We left the courthouse with a sense of joy and began driving to Silivri. Even the distance, which has become complete torture for us as we have to travel every week, felt short. Families were already waiting outside the main gate of the Silivri Prison in the anticipation of seeing their husbands, fathers and brothers again. Everyone was smiling now, carrying on conversations filled with hope despite the biting cold. One family had brought a celebratory band of drummers from Edirne, who were going to play as their relative was released. Everyone’s eyes were fixed on the main gate.

The first few hours were just like a carnival.

Then the mood changed. The crowd started to feel that something was off, but no one had the courage to speak it. In the middle of the night, vehicles that didn’t have official license plates entered the prison one after another, and all of them drove towards Section 9. Later, they set up a barricade to block the view of the parking lot that faced the main gate. A police van entered the prison. Could it be that they had brought them to the prison from the courthouse just now? At some point, armoured vehicles of the gendarmerie special operations command arrived. Wasn’t this much security a bit extreme for a handful of people?

The air of festival had left the crowd, and it had gotten much colder. Still, nobody could bring themselves to speak the fear they held. Many of them started waiting in their cars, saying it was too cold. As I waited inside the car, a friend texted me, telling me to be cautious and sent a tweet posted by some creature:

“We will take’em if you release’em,” it said.

At that moment, in the middle of the night in the Silivri cold, in what was possibly the most secure part of my country, among the gendarmerie and police officers, I feared for the life of the children playing between the parked cars despite the cold air and for the life of my own son.

Dr. Sunay Usluer and her ten-year-old son waited outside the dates of the prison for a release that never came.

What came after was a long and desperate wait; a semblance of hellish torture. All of a sudden, they forbid us to wait near the prison because of the state of emergency, and we were ordered to drive towards the highway slip road; they said those released would be brought there. In that moment, somebody worked up the courage to ask: “Is there a problem?”

“There is no problem Miss, the release procedures are being conducted inside. It’s just taking a bit of time because there are many people. Continue to wait in the area ahead.”

But that “area ahead” kept moving forward. People were constantly driven away further and further from the prison, and finally, they ended up waiting at a spot from where the slip road was invisible. At the entrance to the highway, there was a gendarmerie vehicle, guarded by two privates. Every time we asked them what was going on, they could only tell us: “We can only give you information when our commanders give us information.” At the same time, we kept checking our Twitter feeds. At this point, it became clear that no one would be released tonight, but none in the crowd could drop the slightest flicker of hope and leave, so we waited on and on and on.

There were small children and older people among those waiting. At some point, the vehicles started to leave one by one, eventually, maybe ten or fifteen vehicles remained. My son and I also gave up hope and decided to go home. But as we stopped to ask the gendarmerie private if there had been any developments one last time, we saw a police van in the distance.

We got back into the car and started driving towards the van. As we passed, we caught the attention of a dark silhouette inside the vehicle, who had leant his head against the window. When he saw us in the car, a flash of joy went through his body, he cocked his head and waved at us. It was him: a tiny miracle gave us the information that our supreme state had denied us. Oğuz had been detained again and he was being driven back to Istanbul, to the police department. The police van slowed down for us to pass it. We wanted to drive near again and take a better look, but this time plainclothes officers drove us away.

The hardest part in all of this is to try and maintain one’s composure in front of the children. My son and I lived this experience as if we were having a good time; as if we were in an adventure movie. Neither of us cried. But when we reached home in the early morning hours, we were met with a note by my six-year-old son, who is just learning to write, on the door. “31 March Friday. The happiest day of my life.” His brother and I sat down on the stairs of our building, held each other and burst into tears. How were we to explain to him why his father hadn’t come home?

This was how I saw my husband 15 days ago. After that, he and his co-defendants were kept for in detention seven days at the police station on Vatan Street in Istanbul, which was extended for another seven days. During this time, they sent us his belongings from Silivri Prison; his notes, summaries of books he wrote down. For the past months, he wasn’t allowed to send mail.

I was exhilarated as if I had gotten a pages-long letter; I even read the receipts he had kept from the prison cafeteria. There was also a to-do-list, where he wrote down what he planned to do after his release. The first item on his list was, “Don’t forget about those who remain in prison, and don’t let them be forgotten.” At the end of the day, he is a journalist.

The process that followed was the same as before, police interrogation, another desperate wait at the Çağlayan courthouse during the prosecutor’s questioning and court interrogation, again “what if”; once again disillusionment and ambiguity. What happened to the previous panel of judges only shows the extent of independence of our judiciary and sets the maximum for our expectations.

At the end, they were rearrested on new charges, a decision that didn’t really surprise us. All we could do was say, at least they are back in Silivri Prison, back to their routine, sleeping in a normal bed [as opposed to detention conditions]. I woke up on Saturday and called the prison to find out if they had moved him to a different cell. “Nobody was brought here last night,” the voice at the end of the line said.

I later found out that the police, which drove back to Silivri in a convoy without wasting a second to re-arrest them on the night of 1 April — were simply too lazy to drive back to Silivri on 16 April and they dumped my husband — my partner of 12 years, the father of my children, a yeoman journalist who dedicated 20 years to reporting the news — at Metris Prison [in central İstanbul] like some piece of baggage dropped at storage for safe keeping.

Period.

Dr. Sunay Usluer

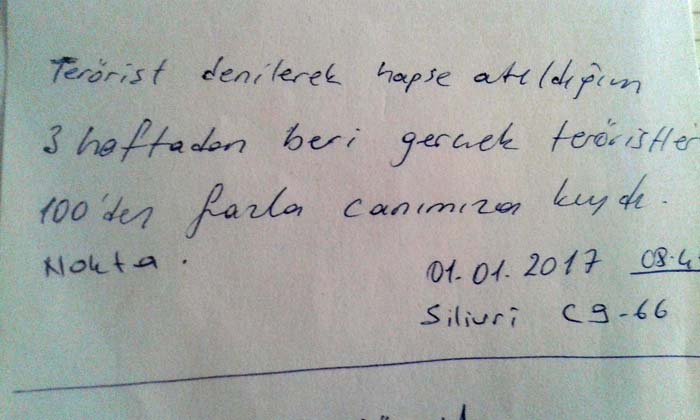

“In the past three weeks, during which I have been imprisoned being declared a terrorist, real terrorists have taken away 100 lives from us.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493981743376-3f86911a-75c7-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

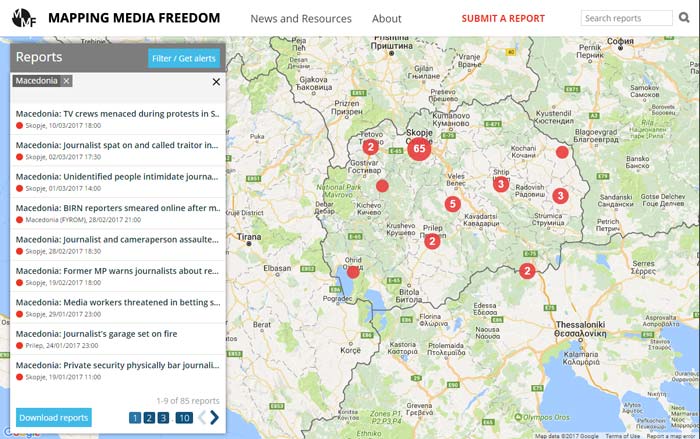

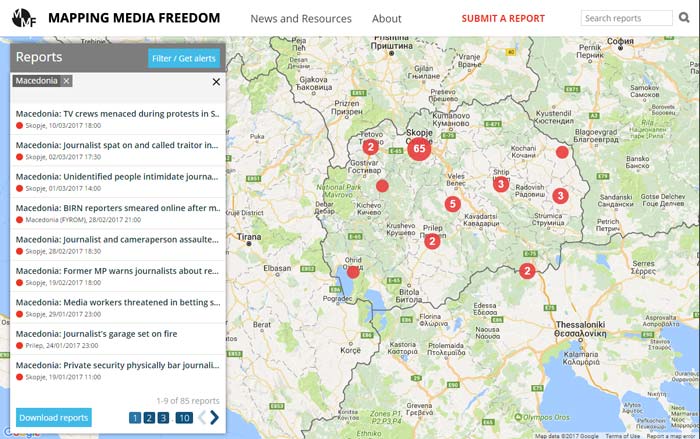

02 May 17 | Campaigns -- Featured, Macedonia, Statements

Index on Censorship signed a joint statement by issued after a ECPMF-EFJ-SEEMO-OBCT fact-finding mission to Macedonia, on 25th-28th April regarding rising violence against journalists in Macedonia:

We hereby express our deep concerns about the yesterday‘s violent attacks against journalists in the parliament of the Republic of Macedonia.

From the beginning of 2016 until yesterday at least 21 attacks against journalists in Macedonia have been registered by the Association of Journalists of Macedonia (ZNM), out of a total of several dozens within the last years. All this clearly demonstrates a rising trend in violence against journalists.

The state of media freedom in the country is very worrying. Attacks on journalists are a direct threat to democracy.

On invitation of ZNM and the Western Balkan´s Regional Platform for Advocating Media Freedom and Journalists Safety the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF) conducted a fact-finding mission to Skopje from 25 to 28 April 2017. The delegation, including the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO) and Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa (OBCT) examined the increased violence against journalists in Macedonia and listened to their experiences.

During the mission, the international delegation so far conducted a total of 13 interviews with 15 representatives of several media outlets, NGO´s, the Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services and the Media Ethics Council. Additionally, the delegation met the Minister of the Interior, Mr Agim Nuhiu.

According to our findings among the main reasons for the increased violence are the following:

- The political climate, anti-media rhetoric and polarisation lead to a highly unsafe environment for journalists.

- There is no political will to ensure conditions for free and independent journalism. State institutions and political stakeholders undertake no responsibility for the protection of journalists.

- The criminal and civil justice systems do not deal effectively with threats and violence against journalists. No implementation of media protection laws and no prosecution of the perpetrators make journalists an easy target.

The signees of this statement condemn any aggression on journalists in Macedonia.

We want to strongly urge the political parties and all related bodies and authorities to prevent further attacks and ensure a safe environment for journalism and freedom of expression. We call on the judiciary and all responsible authorities to stop the ongoing impunity.

- Macedonian authorities must conduct swift and efficient investigations on any single case of attack on physical safety and integrity of journalists. Politicians should refrain from spreading hateful rhetoric that serves violence.

- International conventions protecting human rights and freedom of expression shall be respected.

- The coming ruling coalition and the opposition must comply with Macedonia’s commitment to protect journalism and to guarantee internet freedom. Macedonian authorities must implement without any delay the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on safety of journalists (Recommendation 2016-4) and on Internet freedom (Recommendation 2016-5), adopted on 13 April 2016. Following these standards, any kind of additional state regulation on media content is unacceptable.

- Macedonian authorities must consult for any coming reform in the media sector the legitimate national organisations promoting media freedom and independent journalism: the Council of Media Ethics of Macedonia (SEMM), the Association of Journalists (ZNM), the Trade Union of Journalists (SSNM).

We also call on all journalists to take their role as watchdogs seriously. We encourage them to report and file complaints if they are attacked, intimidated or harassed. They should stand in solidarity with their colleagues, cooperate and support each other.

We, as European media freedom and journalists organisations within the freedom of expression community, stand with our colleagues in Macedonia. We will further observe their situation and raise our voices to support them. There will be a full report on the fact-finding mission in May.

Skopje, 28 April 2017

Signing organisations:

- European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

- European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

- Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso Transeuropa (OBCT)

- South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

- Association of Journalists of Macedonia (ZNM)

- Western Balkan´s Regional Platform for Advocating Media Freedom and Journalists Safety

This statement is endorsed by the following organisations:

- Ethical Journalism Network

- Index on Censorship

- Journalismfund.eu

- Reporters Sans Frontières / Reporters Without Borders

- SCOOP Macedonia

02 May 17 | Index in the Press

A public interest defence should be created to protect journalists and whistleblowers who disclose secret information that reveals serious criminal activity or widespread breaches of human rights, an alliance of free speech organisations has said. Read the full article

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text] London, 3 May 2017. On World Press Freedom Day, Reporters Without Borders – known internationally as Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) – English PEN, and Index on Censorship have

London, 3 May 2017. On World Press Freedom Day, Reporters Without Borders – known internationally as Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF) – English PEN, and Index on Censorship have