15 Dec 14 | About Index, Draw the Line, Young Writers / Artists Programme

Religious freedom and religious radicalism which leads to extremism has become an increasingly difficult balancing act in the digital age where presenting religious superiority through fear and “terror” is possible both locally and internationally at internet speeds.

The ongoing series of beheading videos released by the Islamic State and the showcase of kidnapped school girls by Nigeria’s Boko Haram on YouTube are both examples that test the extent to which the UN Convention of Human Rights can protect religious freedoms. According to a report by the International Humanist and Ethical Union, Egypt’s Youth Ministry are targeting young atheists vocal on social media about the dangers of religion. In Saudi Arabia, Raef Badawi was sentenced to seven years in prison in 2013 and received 600 lashes for discussing other versions of Islam, besides Wahhabism, online.

Article 18 of the Convention states that the “right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance”. The interpretation of “practice” is a grey area – especially when the idea of violence as a form of punishment can be understood differently across various cultures. Is it right to criticise societies operating under Sharia law that include amputation as punishment, ‘hadd’ offences that include theft, and stoning for committing adultery?

Religious extremism should not only be questioned under the categories of violence or social unrest. Earlier this month, religious preservation in India has led to the banning of a Bollywood film scene deemed ‘un-Islamic’ in values. The actress in question was from Pakistan, and sentenced to 26 years in prison for acting out a marriage scene depicting the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter. In Russia, the state has banned the publication of Jehovah’s Witness material as the views are considered extremist.

In an environment where religious freedom is tested under different laws and cultures, where do you draw the line on international grounds to foster positive forms of belief?

This article was posted on 15 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Dec 14 | News and features, Politics and Society, Turkey

On Sunday, December 14, at least 27 people were detained by Turkish police, including journalists, producers and directors of TV shows and police officers. Arrest warrants were issued for at least 31.

The offices of the newspaper Zaman and of the television network Samanyolu TV were raided by police. A warrant for the arrest of Zaman editor in chief Ekrem Dumanlı was at first incomplete, prompting police to return later on Sunday to arrest Dumanlı. Hidayet Karaca, manager of Samanyolu TV, was also detained, as well as Samanyolu producer Salih Asan and director Engin Koç, who were arrested in the city Eskişehir. Warrants were also issued for Makbule Çam Alemdağ, a writer for a Samanyolu show, and Nuh Gönültaş, a columnist for the newspaper Bugün. Bianet has published a list of those detained yesterday.

A large group of protesters gathered outside of Zaman’s Istanbul offices, holding signs that read “Free press cannot be silenced”.

Zaman and Samanyolu TV have been singled out by Turkish President Erdogan for being part of what Erdogan calls a “parallel structure” affiliated with exiled cleric Fethullah Gülen. Erdogan has accused Gülen of being at the centre of plots to topple the government.

The prosecutor in charge of Sunday’s operation said that those detained are being charged with involvement in a terrorist organisation, while some are accused of fraud and slander.

The raids were announced by the Twitter user “Fuat Avni” (a pseudonym) on December 13. Fuat Avni tweeted a list of 47 people for whom there would be arrest warrants.

On Monday Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan attacked the European Union for criticising the arrests that targeted opposition media outlets, telling the EU to “mind its own business.”

“The European Union cannot interfere in steps taken … within the rule of law against elements that threaten our national security,” Erdogan said in a televised speech. “They should mind their own business,” he added, in his first comments after Sunday’s raids.

EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini and enlargement commissioner Johannes Hahn on Sunday condemned police raids as going “against the European values” and said they were “incompatible with the freedom of media, which is a core principle of democracy.”

Recent media freedom violations from Turkey via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com:

EU project overshadowed by arbitrary media ban

BirGün newspaper to undergo investigation for critical coverage

Journalists assaulted, prevented from photographing

Economist and Taraf correspondent threatened on Twitter

Journalist sentenced to community service for insult

This article was updated on 15 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

This article was originally and updated at mediafreedom.ushahidi.com on 15 December 2014

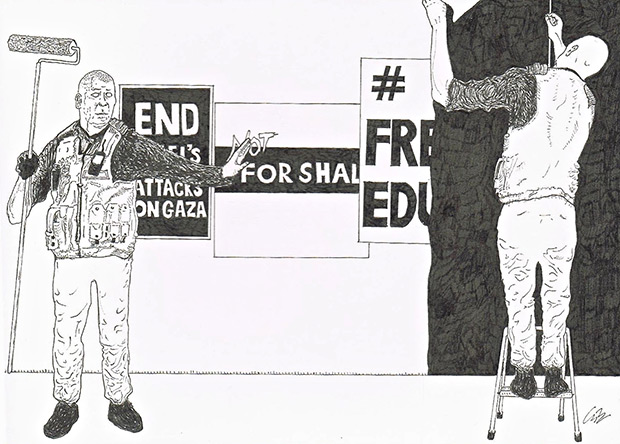

15 Dec 14 | ArtFreedomWales, News and features, United Kingdom

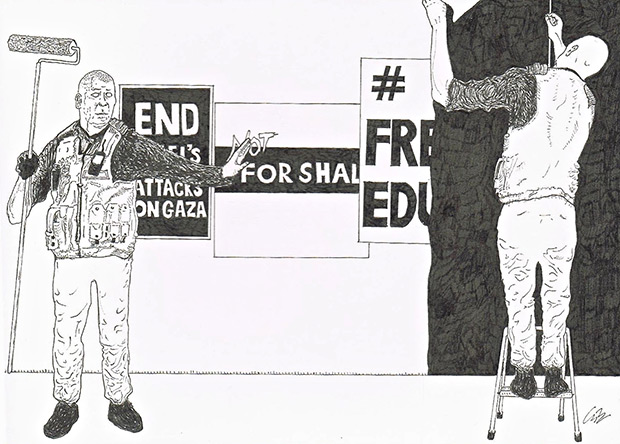

Index on Censorship has been exploring artistic freedom of expression and contemporary forms of censorship in the UK. Who or what controls what is sayable in the arts? Who has a voice in the arts? Do the answers vary as we move around the different member nations of the UK?

Looking at our culture through the prism of artistic freedom of expression opens up questions about the power relations between artists, venues, audiences, the police, the media and community interest.

Our initial case study Beyond Belief – theatre, freedom of expression and the police offered insight into how these relationships are often played out in the present day. Deepening our exploration, conferences in London in 2013 and Belfast in early 2014, have been followed by a programme of work in Wales in the latter half of this year. Art Freedom Wales was Index’s exploration of whether Wales is enjoying its right to artistic free expression.

Across all three projects, it is becoming clear there are massive pressures on what is sayable in the arts–rifts around what is acceptable to funders, to the audience, to public opinion, or even health and safety. It is also clear that there are significant questions around the issue of access to artistic expression–for established and aspiring artists, as well as the public at large. Events this past summer at the Barbican around Brett Bailey’s Exhibit B have underlined recurring questions around the role of the police and the media in shaping what gets to be seen.

In 2015, Index is planning to explore the state of artistic freedom in Scotland before holding a state of the nations event which will bring together key players to discuss how to reinforce support for artistic expression across the UK.

ArtFreedomWales

Over the past few months Index’s project ArtFreedomWales has hosted a series of online discussions with artists from across Wales–established artists, emerging artists and artists working in Welsh. You can catch up with everything that’s been said here.

These discussions, and the issues they raised, informed our approach to a Free Speech Hearing in Cardiff on 27 November. As a culmination of the project, the hearing invited practitioners from across art forms alongside policy makers and cultural gatekeepers to come together to discuss the question “Is Wales enjoying its right to freedom of artistic expression?”

To open the hearing, Index invited Turkish playwright Meltem Arikan, an established artist, with direct experience of censorship who is now living in exile in Wales, to survey the Welsh arts scene from the eye of an outsider.

This was followed with an array of evidence volunteered from across Wales, short presentations surfacing a number of topics from offence to rumour, and self-censorship to cultural education.

Moving from the stage to discussion between peers, major themes and concerns were examined in more detail in breakout sessions.

Finally, a panel discussion featuring Dai Smith (Arts Council Wales), John McGrath (National Theatre Wales), David Anderson (Museums Wales), Lleucu Siencyn (Literature Wales) and Elen ap Robert (Pontio) asked how leading organisations in Wales might take on some of the issues raised during the afternoon?

This article was posted on Dec 10, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Dec 14 | Magazine, Volume 43.03 Autumn 2014

Index on Censorship autumn magazine

In September, Index on Censorship magazine launched a social media campaign which invited its readers to nominate a place which was symbolic of either free speech or censorship, with the winning locations being granted free access to the magazine app for one year.

Nominations came from all over the world and the winning places are Maiden Square in Ukraine, Gezi Park in Turkey and Wigan Pier in the north of England.

You can access the app on iPhone or iPad until 1 September 2015 at any of the three locations listed, by following these steps:

1) Visit the app store or iTunes, searching “Index on Censorship”

2) Download the FREE Index on Censorship app

3) Scroll through the issue to the final page, selecting “Tell me more”

4) Turn the “ByPlace” switch to the right

5) Click OK to activate

See some of the nominations Index magazine received in our Storify below.

For more information on subscribing to Index, click here.

11 Dec 14 | Magazine, News and features, Religion and Culture, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

Neil Gaiman (Photo: Kimberly Butler)

In the next issue of Index on Censorship magazine, fantasy writer Neil Gaiman is interviewed by political cartoonist Martin Rowson about censorship, offence and how graphic novels stir controversy. You can listen to the highlights here and read the full story by subscribing or downloading the app (£1.79 on iTunes).

The interview sees them discussing Dr Who as any example of why we shouldn’t protect children from everything that might scare them; how the Hilary Mantel scandal is keeping the short story alive, and how the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is fighting a never-ending battle. “Comics, because of the capacity of offence that an image can give, will always have one foot in the gutter,” says Gaiman.

Gaiman also opens up about the only time he had to abort collaboration with an artist (“I think that was the only time I’ve looked at something and said: ‘That’s too disturbing.’”) and on the backlash he received from penning the first transsexual character in a mainstream comic (first from Concerned Mothers of America, later from trans activists).

This article is from the upcoming winter edition of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine by Dec 31, 2014 for 25% off a print subscription.

This article was posted on December 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org and is part of the winter 2014 edition of Index on Censorship magazine.

11 Dec 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

I feel sorry for Mario Balotelli. I’m sure he’ll take that as a comfort; knowing he’s not the only one asking “why always Mario?” That is not to say I think he’s drifted through life blameless and immaculate: not at all. I’ve only seen him in the flesh once, when Manchester City played Arsenal. He had a terrible game and got sent off for what even I, sitting in row Z at the other end of the ground, could see was a stupid and dangerous tackle.

But I’ve had a soft spot for Balotelli ever since someone pointed out he looks like a baby dinosaur. Without wishing to infantilise him, he’s like the boy in school who can’t help getting in trouble even when he’s trying to be good. Ballotelli’s current situation is the perfect example. Last week, the player posted an image on Instagram, showing Nintendo character Super Mario (from whom the footballer takes his nickname, or at least would like to).

“Don’t be racist!”, it read (Yay!)

“Be like Mario” (LOL!)

“He’s an Italian plumber” (indeed he is)

“created by Japanese people” (correct)

“who speaks English” (sort of)

“and looks like a Mexican” (I suppose he does. A bit.)

“…jumps like a black man” (hmmm)

“and grabs coins like a Jew” (oh)

Long story short: people suggested that this might be a bit racist towards black and Jewish people, Balotelli responded that his mum is Jewish. Eventually, he took the post down and apologised. But by then it was too late. The Football Association announced over the weekend that the striker would face an investigation for using insulting and improper language with “reference to ethnic origin and/or colour and/or race and/or nationality and/or religion or belief”.

For what it’s worth, I don’t believe for a moment that Balotelli meant to insult anyone with his Instagram post. I think he entirely sincerely posted the meme seeing it as an anti-racist message. The problem for poor Mario was that his ill-judged but innocent Instagram came while the football world was actually paying attention to anti-semitism, as Wigan chairman Dave Whelan spouted a series of inappropriate race-related comments (Jews, money, you know, that stuff) after hiring former Cardiff manager Malky Mackay, who himself had run into controversy over dubious texts (Jews, money, on and on it goes).

Whelan stylishly compounded the issue with a “clarifying” interview in the Jewish Telegraph, where he spun the ”some of my best friends are…” line, saying there must be “a dozen” Jews with apartments near his residence in Majorca, and “so many Jewish people go to Barbados at Christmas. That’s when I go. I see a lot of them in the Lone Star, in restaurants. I play golf with a few of them.”

In the same interview, Whelan told how when he was younger, people called the only Chinese restaurant in Wigan “the Chingalings”, and absolutely nobody had minded (though one doubts anyone asked the Chinese people of Wigan).

Whelan now also faces charges of misconduct from the FA. I’m not about to suggest that the FA has no right to investigate Whelan, or anyone involved in professional football in England. Associations can have their own rules and standards. But it would be sad if, in football’s newfound determination to deal with discrimination, innocents such as Balotelli got caught in the dragnet.

The interesting question is whether, in combating racism, one confronts the words used, the stereotypes invoked, the intent behind them, or all three at once. Is it possible to disentangle the three?

Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than the debate about whether Tottenham Hotspur fans should be able to chant “yids” or not. Short explanation: some Spurs fans are Jewish, many identify as the “yid army”. Some people — mostly not Spurs fans — feel that Spurs fans chanting “yids” legitimises anti-semitic chanting by fans of other teams. Spurs fans say it’s their chant and their word and they are using it positively. Unpick that one, sports fans.

Words in and of themselves are neutral entities. Does saying the word “yid” — in and of itself — make me more or less anti-semitic? No. But the creation of a taboo can elevate a word, bringing a certain thrill to its use. In a society where, more or less, we have decided bigotry is a bad thing (which is not to suggest a society where bigotry is no longer a problem), the use of words and phrases associated with bigotry can take on a thrill of its own, as much for the well intentioned as for the malevolent. The bad taste joke, the inappropriate interjection, the drunken football chant using the words you might not be supposed to use, are the shared cigarette behind the school bike shed; the shared, line-crossing moments that so often bond people.

The joy for most Unilad Bantalopes lies in that shared bond. For the person who created the meme which ill-feted Mario Balotelli shared (very much from the Bantasauraus school), one could simultaneously attempt to be anti-racist and use racial stereotypes. Human beings are complicated like that. And that’s why a zero-tolerance approach to words and meanings is unlikely to work on us.

This article was posted on 11 December 2014 at indexoncensorship

10 Dec 14 | Awards, Pakistan

Malala Yousafzai Photo: (©Torbjørn Kjosvold/FMS/CreativeCommons/Flickr)

Pakistani education campaigner Malala Yousafzai will accept the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize today in Oslo. Yousafzai shares the award with Kailash Satyarthi, an Indian children’s rights activist. The ceremony can be viewed live at 11:50am GMT.

Yousafzai was awarded the Doughty Street Chambers Advocacy award based on her work at the 2013 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards.

In October 2012, a Taliban gunman shot education campaigner Malala Yousafzai in the head and chest for her activism, as she was returning home from school in Pakistan’s Swat district. After months of treatment, she returned to school in Birmingham later that year.

The schoolgirl’s father, Ziauddin Yousafzai, accepted the award on his daughter’s behalf saying:‘I want to give a message to the world. I didn’t do anything special. As a father, I did one thing, I gave her the right of freedom of expression. All fathers and mothers, give your daughters and sons freedom of expression. Freedom of expression is a most important right. The solution of any conflict is to say the right thing, to speak the truth.’

At 17, Yousafzai is the youngest ever winner of the Nobel Prize. Fellow recipient, Kailash Satyarthi has lead various peaceful protests and demonstrations, focusing on the exploitation of children for financial gain. He formed the Bachpan Bachao Andolan, translated as, Save the Childhood Movement, which combats child labour.

Kailash Satyarthi (Photo: ©José Cruz/Agência Senado/CreativeCommons/Flickr)

This article was posted on 10 Oct 2014 at indexoncensorship.org.

09 Dec 14 | About Index, Campaigns, Draw the Line, Young Writers / Artists Programme, Youth Board

The second cohort of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board was announced today. The members will discuss topical freedom of expression events, participate in #IndexDrawtheLine debates and advise Index on youth issues. The new board will sit from December 2014 to May 2015.

Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board:

Abishek Phadnis

Abishek Phadnis

Abhishek recently completed a Master’s in Diplomatic History from the London School of Economics, and is due to commence doctoral research on an early history of the Indian nuclear weapons programme. As a secularist activist and a fierce campaigner against theocratic censorship in England, he has been honoured by the British National Secular Society for “bravely challenging Islamist groups, his own university (LSE) and Universities UK over important and fundamental issues such as free speech.

Ásta Helgadóttir

Ásta Helgadóttir

Ásta is a deputy member of the Icelandic Parliament for the Icelandic Pirate Party and will take position as an MP in the fall of 2015. Her interest in censorship is both political and academic, mainly focused on the aspects of European legal justifications regarding modern day technological censorship.

Catarina Demony

Catarina Demony

Catarina is the founder of The Voiceless, a media platform about human rights violations, and recently graduated from Kingston University with a Journalism degree. Currently, she works in the communications team at London School of Economics Students’ Union, as well as University of the Arts. Catarina also works closely with Amnesty LDN, part of Amnesty International movement for recent graduates and young professionals.

Jordan Mitchell

Jordan Mitchell

Jordan is a human rights advocate, writer, and Truth About Youth associate working with Ovalhouse Theatre. Based in London, he believes it is imperative for the under-represented to be given a platform, with a particular focus on the role of the media.

Kay Robinson

Kay Robinson

Kay is studying History and Politics at Lancaster University, and is sub-editor for the International Political Forum. A strong supporter of human rights, she believes that free and equal platforms of expression have a crucial role in forming safe, empowered societies.

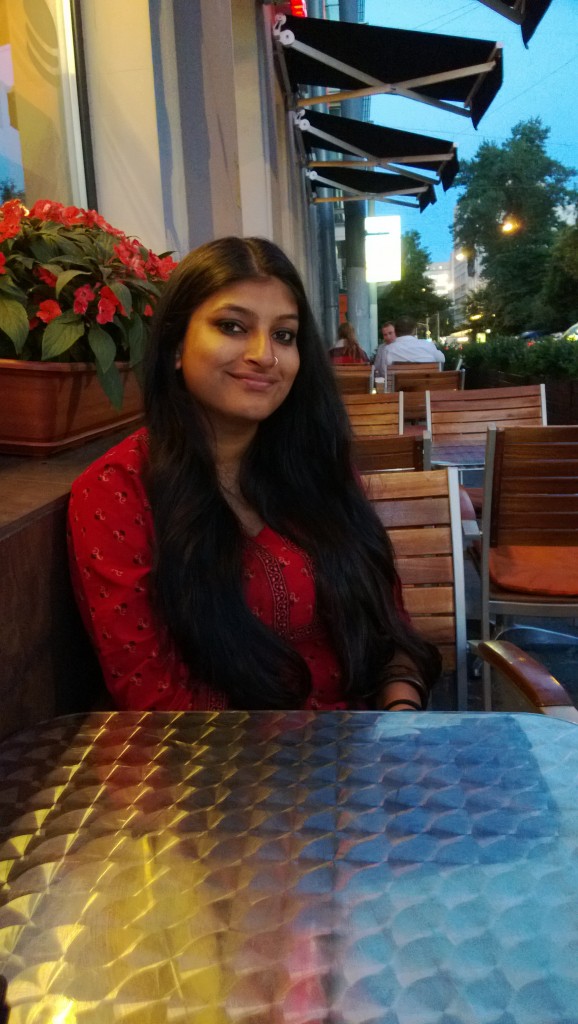

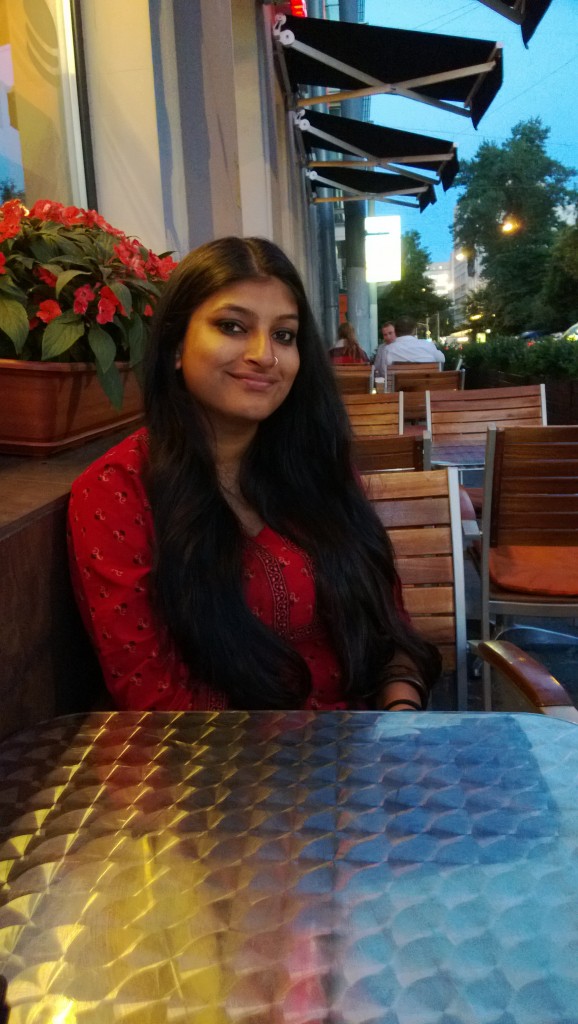

Mahima Singh

Mahima Singh

Mahima works for newslaundry.com, an independent media website in India. Mahima believes that the freedom of expression is one of the core fundamentals of a healthy society . She has been advocating freedom since her college days when she was forced to take down a story she had written because it upset the authority.

Mari Shibata

Mari Shibata

Mari is a freelance newsgatherer for AP Television, a BFI-funded filmmaker and ocassional writer for Vice. Also a Cambridge University graduate in music, she is passionate about issues surrounding free expression in the cultural arts from conflict zones.

Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary

Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary

Mohanad is an Egyptian Engineering major in the Middle East. With the Arab uprisings over the last few years, his passions for freedom of expression and human rights were further consolidated. Mohanad is currently secretary, editor and founding member at a university club called ‘Fikir’ (meaning ‘thought’) that aims to encourage social involvement and responsibility.

The application period for the next youth board will open in May 2015 for the June to November cohort.

What is the youth board?

The youth board is a specially selected group of young people aged 16-25 who will advise and inform Index on Censorship’s work, supporting our ambition to fight for free expression all around the world and ensuring our engagement with issues relevant to tomorrow’s leaders.

Why has Index started a youth board?

Index on Censorship is committed to fighting censorship not only now, but also in future generations, and we want to ensure that the realities and challenges experienced by young people in today’s world are properly reflected in our work.

Index is also aware that there are many who would like to commit some or all of their professional lives to fighting for human rights and the youth board is our way of supporting the broadest range of young people to develop their voice, find paths to freely expressing it and potential future employment in the human rights/media/arts sectors.

What does the youth board do?

Board members meet once a month via Google Hangout to discuss the most pressing freedom of expression issues of the moment and to set a monthly question for our project, Draw the Line. You will be expected to write a minimum of 1 blog post introducing/concluding the question of the month and to help us spread the word about Index.

There is also the opportunity to get involved with events such as debates and workshops for our work with young people and also events such as our annual Index Freedom of Expression Awards and Index magazine launches.

How do people get on the youth board?

Each youth board will sit for a term of 6 months.

Current board members are invited to reapply up to one time.

The board will be selected by Index on Censorship in an open and transparent manner and in accordance with our commitment to promoting diversity.

Why join the Index on Censorship youth board?

You get the chance to be associated with a prestigious media and human rights organisation and have the opportunity to discuss issues you feel strongly about with Index and with other amazing young people (internationally). At each Board meeting we will also give you the chance to speak to someone senior within Index or the media/human rights/arts sectors, helping you to develop your knowledge and extend your personal networks and you’ll be featured on our website.

09 Dec 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Magazine, News and features, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

Campaigners outside the Baku court where members of N!DA were being sentenced (Photo: © Jahangir Yusif)

Azerbaijani activists Rasul Jafarov and Rebecca Vincent wrote an article for Index on Censorship magazine in December 2013 covering attacks on photojournalists, featured alongside a photo essay by photographers. A year later, the magazine asked Vincent to return to the issue, and cover how the past year has meant increasing risks for photographers, journalists and activists. One of the original photographers Jahangir Yusif returns to Index to illustrate the story. Jafarov is currently detained by the government, awaiting trial. Below, is a preview of the article to be featured in the next issue of the magazine.

Azerbaijani human rights defender Rasul Jafarov and I co-authored a piece for Index on Censorship magazine on behalf of the Art for Democracy campaign, focusing on the pressure faced by Azerbaijani photographers who covered risky topics such as corruption and human rights abuses. The piece ran alongside a photo story by some of the country’s most talented independent photographers.

That piece was typical of the work of the Art for Democracy campaign, which used all forms of artistic expression to promote democracy and human rights in Azerbaijan. Now, a year later, the human rights situation in Azerbaijan has worsened immeasurably. Rasul Jafarov was arrested and remains in detention, facing a serious jail sentence on fabricated and politically motivated charges, alongside a number of other prominent human rights defenders. Art for Democracy’s activities have been effectively suspended, as well as the operations of nearly all of the remaining human rights NGOs in the country.

Indeed, the past year has seen the most unprecedented of all human rights crackdowns to date in Azerbaijan, as the authorities work aggressively to silence the country’s few remaining voices. As a result, there are currently more than 90 reported political prisoners in Azerbaijan, including some of the country’s leading human rights defenders, lawyers, journalists, and bloggers.

Police and activists clash during the run-up to the presidential election (Photo: © Jahangir Yusif)

Rasul Jafarov’s case bears all the hallmarks of the pressure exerted on human rights defenders in Azerbaijan. He had been on the authorities’ radar for years, with his earlier work for the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety and, since December 2010, in his role as the founder and Chairman of the Human Rights Club. Perhaps most notably, Jafarov co-ordinated the Sing for Democracy campaign, which used the May 2012 Eurovision Song Contest, held in the capital Baku, as a platform to expose on-going human rights violations in the country and promote democratic change. He was the driving force behind the creation of the Art for Democracy campaign.

Alongside Art for Democracy’s activities, Jafarov worked to expose the situation of political prisoners. On the eve of the October 2013 presidential election the Human Rights Club released a list Jafarov had compiled of political prisoners, revealing a shocking 144 cases. The election itself was marred by widespread electoral fraud and saw incumbent President Ilham Aliyev re-elected for a third term in office.

In 2014, Jafarov continued working on the list and coordinating efforts among NGOs to achieve consensus and develop a joint version of the list, which would prove crucial to international advocacy efforts. Along with some of the other human rights defenders who have since been targeted, Jafarov repeatedly raised the issue at the Council of Europe, and advocated the appointment of a new special rapporteur to take up the work of a previous rapporteur whose efforts were defeated by lobbying from the Azerbaijani government. Jafarov also announced plans to launch a new campaign, Sports for Rights, ahead of the first European Games, which are due to be held in Baku in June 2015.

As a result of these activities, Jafarov faced a number of pressures from the authorities, but he persevered. He was aware of the risks, but also remained hopeful that the situation in his country would improve. He was dedicated to his work defending the rights of others and attempting to hold his government to account. Indeed he remains passionately committed to these aims even now, in detention.

After having his bank account frozen and being prevented from travelling outside of the country, Jafarov was arrested on 2 August and charged with illegal entrepreneurship, abuse of office, and tax evasion. The fabricated and politically motivated charges were similar to those used against other prominent human rights defenders. Some of the charges were linked to the fact that the Human Rights Club remained unregistered, despite the fact that Jafarov had been attempting to register the NGO with the state for more than three years, an issue pending consideration by the European Court of Human Rights. Jafarov remains held at the Kurdekhani detention centre, awaiting trial.

Jafarov is only one of many prominent human rights defenders to have been targeted in Azerbaijan in recent months. On 26 May, the chairman of the Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Centre Anar Mammadli, was sentenced to five and a half years in jail, and his colleague Bashir Suleymanli to three and a half years on charges including illegal entrepreneurship, abuse of office, and tax evasion. Elnur Mammadov of the International Cooperation of Volunteers’ Union was also sentenced to two years on probation.

Protesters campaign for the release of imprisoned activists (Photo: © Jahangir Yusif)

On 30 July, the head of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, Leyla Yunus, was arrested on politically motivated charges of treason, fraud, forgery, tax evasion, and abuse of office. Her husband, an activist in his own right, Arif Yunus, was arrested on 5 August on charges of treason and fraud. On 8 August, the head of the Legal Education Society Intigam Aliyev was arrested on similar politically motivated charges: illegal entrepreneurship, abuse of office, and tax evasion. There are now a total of nine human rights defenders behind bars in Azerbaijan. In addition, the whereabouts of the director of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety Emin Huseynov have been unknown since 8 August, the day his organisation’s office was searched and sealed shut by police.

Parallel to these arrests, the authorities have stepped up other forms of pressure against both local and foreign NGOs, making it nearly impossible for organisations working on issues related to human rights and democracy to continue operating in the country. This has resulted in the closure or suspension of activities of many of the remaining human rights NGOs in the country. Parliament continues to tighten legislation related to the operations and financing of NGOs, cutting off vital sources of funding for independent groups and making it difficult to carry out even routine activities.

At the same time, other violations continue, such as pressure against the few remaining opposition and independent media outlets in the country. Prominent investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was arrested on 5 December, as government officials and their supporters employed new tactics in their relentless attempts to silence her. Journalists Seymur Khaziyev and Khalid Garayev, both presenters of the Azerbaijan Hour programme, were arrested on 29 August and 29 October respectively, bringing the current total of journalists and bloggers behind bars to 15. The Azadliq newspaper, the country’s main opposition daily newspaper, teeters on the brink of closure, facing serious financial hardship because of excessive fines from civil defamation lawsuits and a number of other pressures from the authorities.

In an ironic twist of fate, in the midst of this unprecedented crackdown, Azerbaijan in May 2014 assumed the chairmanship of Council of Europe, a body whose very purpose is to safeguard human rights and democratic values. Sadly, during Azerbaijan’s chairmanship, the Council of Europe, and, the broader international community, has done little to hold the government to account for its human rights obligations.

Now, with Jafarov and so many of his colleagues behind bars and the organisations they represent effectively paralysed, concrete international support is needed more than ever. Azerbaijan’s few remaining independent voices are under siege and will not be able to hold out much longer.

©Rebecca Vincent

www.indexoncensorship.org

Rebecca Vincent is a human rights activist and former diplomat who writes regularly on human rights issues in Azerbaijan. She served as advocacy director of the Art for Democracy campaign until April 2014

Jahangir Yusif is a photo-journalist whose work was featured in the original article 12 months ago, read the original article here.

Index recently was part of a protest at the Azerbaijani embassy, read more about it here.

This article is from the upcoming winter edition of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine by Dec 31, 2014 for 25% off a print subscription.

This article was posted on 9 December 2014 and appears in print as Azeri attack in the Winter 2014 Index on Censorship magazine.

09 Dec 14 | Bahrain, News and features

Bahraini human rights activist Zainab Al-Khawaja was handed an additional 16 month sentence for insulting a public official, according to her sister Maryam Al-Khawaja, co-director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights.

Last week, Zainab Al-Khawaja was sentenced to three years in prison and fined 3,000 Bahraini Dinar (£5,000). She was on trial for tearing up a photo of King Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa at an October court date where she faced charges connected to previous rights campaigning. This comes only a week after she gave birth to her second child.

In a tweet, Maryam Al-Khawaja criticised the United Kingdom’s decision to move forward with a military base in Bahrain. “UK basically gave Bahrain regime a free pass to do pretty much anything they want,” she wrote.

The Al-Khawaja family have been heavily involved in Bahrain’s pro-democracy movement, and have been continuously targeted by authorities in the constitutional monarchy.

Al-Khawaja’s father Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja has been serving a life sentence since 2011 for the role he played in the country’s ongoing protest movement which started that year. Her sister Maryam Al-Khawaja boycotted the recent court hearing which saw her sentenced to one year in prison on what is widely acknowledged to be trumped up charges.

This article was posted on 9 December 2014 at indexoncensorship

08 Dec 14 | Academic Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

This article was posted on 8 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

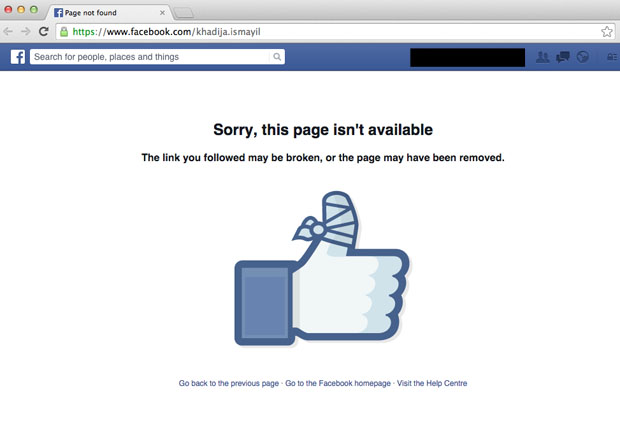

05 Dec 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News and features

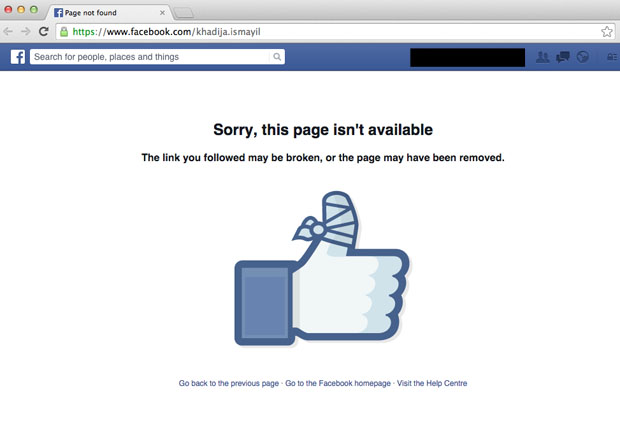

Khadija Ismayilova

The arrest of Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova today underscores the entrenched authoritarian instincts of the government of President Ilham Aliyev. Ismayilova was sentenced to a two month pretrial detention.

“The arrest of Khadija Ismayilova is part of Azerbaijan’s continued crackdown on free media and civil society. This confirms the pattern of intimidation and harassment perpetrated by authorities in an attempt to silence critical voices,” Melody Patry, senior advocacy officer at Index on Censorship, said.

Ismayilova’s arrest follows the earlier detentions of human rights defenders Leyla Yunus and her husband Arif Yunus; free speech advocate Rasul Jafarov; journalists Seymur Hezi, Parviz Hashimli, Nijat Aliyev and Sardar Alibeyli; and bloggers Omar Mamedov, Abdul Abilov and Rashad Ramazano. The country has starved the 2014 Index award winning Azadliq newspaper of resources, forcing it to suspend its print edition. The charges against all of the detainees range from hooliganism to illegal storage and sale of drugs.

Today’s action by Azerbaijan’s authorities also drew immediate criticism from Human Rights House Foundation Executive Director Maria Dahle and the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović.

“This sentence does not come as a surprise: we assumed the authorities wanted to silence Khadija Ismayilova,” said Dahle. “The arrest has a chilling effect: one must now consider that every independent civil society leader in Azerbaijan is a target and can be arrested at any given time for any charge, as ludicrous as one can imagine. The international community, especially the Council of Europe, must now get a foot in the door to stop the repression, including by stopping further cooperation with Azerbaijan’s authorities”, Dahle added.

“The arrest of Ismayilova is nothing but orchestrated intimidation, which is a part of the ongoing campaign aimed at silencing her free and critical voice,” Mijatović said.

On Friday afternoon, Ismayilova’s usually very active Facebook page was also inaccessible.

Azerbaijan, which spends significant amounts on media relations, presents itself as a modern nation. But behind the smokescreen, the country has been carrying out a systematic suppression of civil society, journalists and independent media.

This article was posted on 5 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Abishek Phadnis

Abishek Phadnis Ásta Helgadóttir

Ásta Helgadóttir Catarina Demony

Catarina Demony Jordan Mitchell

Jordan Mitchell Kay Robinson

Kay Robinson Mahima Singh

Mahima Singh Mari Shibata

Mari Shibata Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary

Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary