24 Nov 14 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El Sisi has tightened the screws of the country’s journalists. (Photo: Wikipedia)

In a rare show of defiance, hundreds of Egyptian journalists have objected to a “statement of allegiance” to the government signed by editors-in-chief of the main state-owned and independent newspapers.

More than 600 Egyptian journalists signed an online petition defending press freedom and rejecting censorship in all its forms. The move came in response to a loyalty pledge by 17 editors-in-chief of newspapers to refrain from criticizing the police, the military and the judiciary at this sensitive time when Egypt was “at war with terrorism.”

The journalists dismissed the editors’ statement as “a futile attempt to create a one-voice media,” arguing that “fighting terrorism had nothing to do with voluntary abandonment of freedom of speech.”

“The editors’ statement is not worth the ink used in writing it,” Dina Samak, deputy editor-in-chief of the English language semi-official Ahram Online and one of the journalists who signed the petition, told Index on Censorship.

“The terrorists will win when they can control the media, and the state will fall when it agrees on the same goal,” said Khaled El Balshi, a journalist and board member of the Journalists Syndicate, who helped draw up the petition for press freedom.

In a show of solidarity with Egypt’s military-backed regime, the editors had gathered at El Wafd newspaper headquarters on 26 October to forge “a united front against terrorism”, expressing their “rejection of attempts to cast doubt on state institutions.” They also vowed to take measures to halt what they called the “infiltration by elements supporting terrorism” in their publications — a reference to supporters of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood, designated as a terrorist group by Egypt last year.

While the move did not come as a surprise to many — as it was already clear that the majority of media outlets had aligned themselves closely with the government since the military takeover of the country in July 2013 — the “loyalty pledge” by the editors was nevertheless unusual even in a country where the media was in lockstep with the regime.

The signatories to the declaration — the editors-in-chief of the three main state-owned dailies Al Ahram, Al Akhbar, Al Gomhouria and those of the independent Al Masry Al Youm, Al Watan, Al Shorouq, El Tahrir, El Ahali, Al Fajr , El Messa, El Esboo, El Youm el Sabe and El Gamaheer newspapers — argued however that “crisis situations” required “exceptional measures”.

Defending the editors’ statement, Emad El Din, editor-in-chief of the independent Al Shorouk denied that the editors’ loyalty declaration gave journalists the green light to practice self censorship.

“We wanted to deliver a message to citizens that the media is with the state in fighting terrorism,” he told NPR Radio shortly after signing the statement.

“At this time of heightened nationalism, the climate does not allow for any criticism of the government,” he added.

The move came in response to a call by President Abdel Fattah El Sisi for Egyptians to rally behind him in his fight against terrorism following two deadly militant attacks on an army checkpoint in North Sinai on 24 October that killed 33 army soldiers and injured at least a dozen others. The militant assaults were the latest in a string of attacks targeting mainly security forces — but at times, also civilians — since the overthrow of Islamist President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013. The attacks have prompted a surge in nationalism and a heralding of a so-called “war on terrorism” waged by the military against suspect-militants in the Sinai Peninsula. The violence has also resulted in a massive government crackdown on dissent that has targeted all opposition including journalists critical of regime policies.

Six journalists have been killed and dozens detained since the military took power in July 2013, according to the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists. While most have been released, at least 11 journalists remain behind bars for no crime other than being at — or near — Muslim Brotherhood protest sites. Among the detained are three journalists working for the Al Jazeera English news network who have been sentenced to between seven and 10 years in jail on charges of “threatening national security, fabricating news and aiding a terror group”.

The crackdown on the media has led many journalists to practice self-censorship for fear of being imprisoned, killed or labeled “unpatriotic” by an unsympathising Egyptian public. Meanwhile, the statement released by the editors has fueled fears among press freedom advocates of a further shrinking in the already-dwindling space for freedom of expression in Egypt.

Adel Hamouda, an Egyptian journalist and former editor-in-chief of Al Fajr, meanwhile, criticised the editors’ statement as “uncalled for“.

“It is an attempt by the editors to win favour with the regime for the sake of personal gains,” he told Index. He explained that all Egyptians — except those supporting the Muslim Brotherhood — support the state in its war on terror so it is “meaningless” to publicly assert their support. He further noted that all media organisations were required to seek approval from the Armed Forces Morale Affairs Department before publishing or broadcasting any news about the military.

The majority of the independent media outlets that signed the statement belong to wealthy businessmen with close links to the ruling military-backed regime. They are fully aware that publishing any criticism of government policies would ruffle feathers and likely jeopardize their business interests. All top editors were appointed by the Higher Press Council shortly after Morsi’s overthrow in July 2013. Their selection was clearly based on their willingness to cooperate with the regime rather than their merits. Shortly after Morsi’s ouster, a leaked video on YouTube showed then-Defence Minister Abdel Fattah El Sisi asking senior generals to “establish partnerships with media outlets to curb any criticism of the military”. An independent journalist who spoke on condition of anonymity told Index that days before Morsi’s ouster, she had been approached by security officials who promised her “fruitful rewards” if she joined the “winning side” — a clear reference to the country’s powerful security apparatus that drove the uprising against the democratically-elected president.

In the coup’s aftermath, most editors and TV talk show hosts have persistently lionised Sisi and cheered on the military while demonising the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist group from which former President Mohamed Morsi hailed.

The media in Egypt has traditionally been a propaganda tool for whoever is in power. Various successive regimes have used the state media as a mouthpiece to further their political gains. Under Mubarak, all editors-in-chief of the state-owned newspapers were handpicked by his powerful Minister of Information Safwat El Sherif who presented the list of chosen candidates to the Shoura or Consultative Council, the upper house of parliament dominated by members of the then-ruling party, the National Democratic Party, for ratification.

In the months following the fall of Mubarak, there was a brief period of free expression and a loosening up of restrictions on the media. Press freedom — one of the major gains of the 2011 mass uprising — was short-lived however as the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) which replaced Mubarak, quickly moved to exercise control over the media. During its one year in office, the SCAF confiscated newspapers, ransacked the offices of foreign news networks and investigated journalists critical of the military. Shortly after Morsi won the elections — becoming the country’s first democratically elected president — he too reneged on his election promises to promote freedom of speech, appointing a Muslim Brotherhood member as minister of information. The Muslim Brotherhood-dominated Shoura appointed regime loyalists as senior editors of state-owned dailies, repeating the Mubarak-era practice that allows tight government control over the media. The move provoked an outcry from non-Islamist journalists who held protest rallies and threatened to resign their posts.

Almost immediately after Morsi’s overthrow, all Islamist-leaning newspapers and TV channels were shut down by the new authorities — a move that sent a message to journalists that there was little tolerance for dissent in Egypt, post-3 July. The last sixteen months have seen a return of the media censorship reminiscent of that which prevailed under Mubarak. Newspapers that published articles deemed “controversial” by the authorities, have been pulled off newsstands and confiscated. In October 2014, a print edition of the independent Al Masry Al Youm was confiscated by government censors for publishing an interview with former national security intelligence chief Mohamed Gebril in which he was quoted as saying that “no Israeli spy has ever been executed in Egypt”. The paper later appeared on newsstands, albeit without the interview. Months earlier, columnist and screenwriter Belal Fadl resigned from the independent Al Shorouk after the paper’s management allegedly refused to publish his column ridiculing the promotion of Sisi (who was defence minister at the time) to the rank of field marshal. Fadl was accused by pro-military commentators of being a “traitor” and “a fifth columnist plotting to destroy the country”.

Several editors who signed the statement of support to the government are also known to be part of a fake opposition created by Mubarak to give a semblance of free speech and democracy. Like other pro-regime editors, they too have persistently glorified the military and vilified the Muslim Brotherhood. And they have gone a step further, slandering the January 25 Revolution as a “foreign conspiracy” and labelling the secular opposition activists who mobilised public support for the 2011 mass protests “traitors” and “foreign agents.”

Mostafa Bakri, editor-in-chief of Al Osbou — and one of the editors who signed the loyalty pledge — has recently been summoned by the public prosecutor after several legal complaints were filed against him by private citizens for “fabricating news” and “slandering the January 25 Revolution”.

Meanwhile, the journalists behind the online petition for press freedom are planning to form an independent association to advocate freedom of expression. While this is a step in the right direction, press freedom advocates fear the negative effects of the editors’ pledge of allegiance are already being felt.

“Their statement was perceived as a warning message by the younger, less skilled journalists, many of whom are now practicing self-censorship for fear of losing their jobs or in a bid to win favour with the management and get promoted,” lamented Dina Samak.

Despite the setback, the battle for press freedom is on.

“It is a battle pitting the younger, pro-reform journalists against the old regime loyalists, resisting change,” Amany Kamal, a former radio presenter told Index. Kamal was forced to quit her job as a broadcaster with a state-run radio channel after being accused by the management of sympathising with the Muslim Brotherhood. “But we shall win,” she said.

This article was published on 24 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Nov 14 | Azerbaijan News, News and features, Politics and Society

Impunity is a festering sore on freedom of the press. Harassment, violence and murder of journalists are problems around the world — even in Europe, as Index’s project mapping media violations has shown. The numbers speak for themselves: of the 370 media workers murdered in connection with their job over the past ten years, 90% have been murdered without their killers being punished. Many of these crimes aren’t even investigated.

Ahead of the International Day to End Impunity, journalists from across the world told Index why impunity is such a danger to free expression and a free press.

Kostas Vaxevanis, Greek investigative journalist, HOT DOC, and 2013 Index award winner

Impunity generates corruption and its enemy is the one thing that exposes and threatens it: the freedom of the press.

The HOT DOC is currently facing 40 lawsuits mainly from ministers and politicians in an attempt to shut us down as journalists. We reveal scandals like one with the minister of justice, a former judge who committed an “error” that granted amnesty to officials who had abused public funds, and instead of answering in public as required as politicians, we are being sued. We pester the courts and despite winning lawsuits, we need more than 80,000 euro per year for court expenses.

Heather Brooke, British-American journalist and 2010 Index award winner

It is a problem that journalists around the world get threatened, intimidated and killed just for doing their job.

These crimes, like any other crime, need to be investigated. If not, it sends a message that this is okay; that the law is only for certain people. It is an implicit acceptance of this behaviour.

If we want to have a strong press, threats, intimidation and murder of journalists can’t be seen to be implicitly condoned by the state. It’s a dangerous message. It makes people frightened to ask tough questions, and if that happens, you are on the way to shutting down a robust press.

Kareem Amer, Egyptian blogger and 2007 Index award winner

I come from a country where we have a lack of justice. The executive power controls the parliament and the justice system. People feel that if they get mistreated or oppressed by those in power nothing will protect them or bring them justice.

Not only people who express their opinions suffer from a lack of justice. People from different backgrounds who have a different way of thinking and different interests also don’t trust the justice system. Those who have more power can easily avoid punishment and take revenge against victims who tried to get their rights through judiciary system.

Officially, police officers don’t have any kind of formal immunity. According to the law they can be questioned if they violate the rights of people by torturing or murdering. But, in fact, all those accused of killing protesters and torturing prisoners managed to avoid being punished, with a few exceptions.

I feel that it’s not safe to express your opinions freely in a country where people can easily avoid punishment.

I have been sentenced to four years in jail for writing two articles and publishing them on the internet, and during that time I have been through physical violence and mistreatment committed by security forces. I reported it but no one has been questioned or punished. That made me feel that there is no justice in my country and that it is easy to be humiliated and tortured and you will not get protected, since the judiciary system is practically part of the executive power and the judges do what the authorities want them to do.

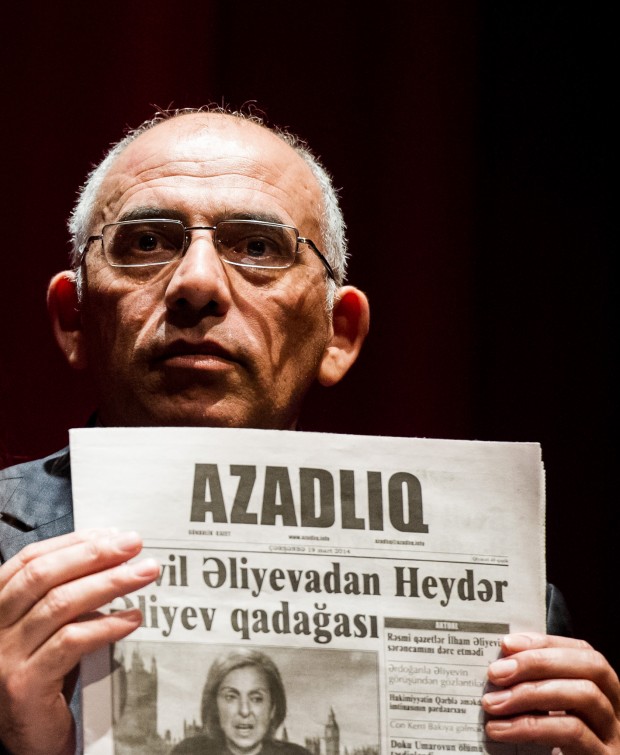

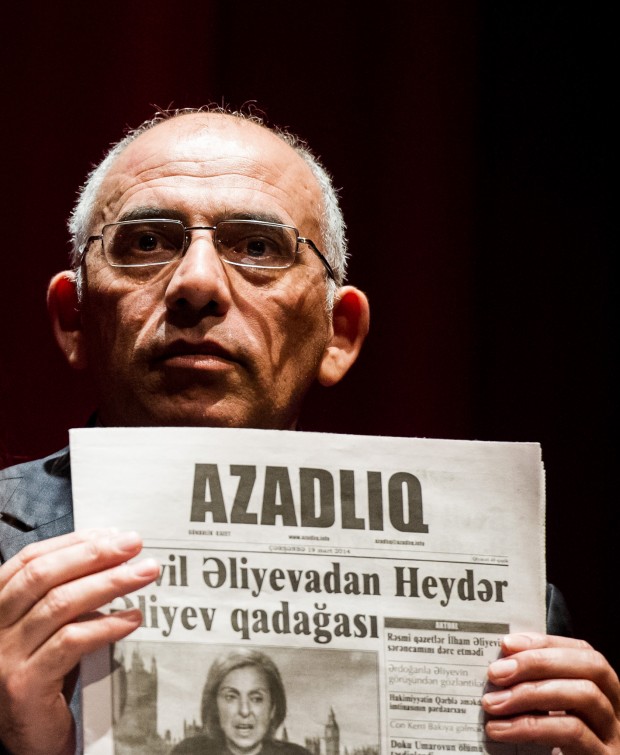

Rahim Haciyev, Azerbajiani journalist and acting editor of 2014 Index award winner Azadliq

Rahim Haciyev, deputy editor-in-chief of Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Freedom of expression is the basis of all other rights and freedoms. Free speech is something all authoritarian regimes are worried about as it threatens their existence. That is why freedom of expression is specifically targeted by authoritarian regimes. If there are no free people, there is no freedom of expression. Free speech is a precondition for journalists to be able to work in full strength and thus fulfill their functions in society. Authoritarian regimes organise permanent attacks on journalists with impunity. A free journalist armed with freedom of expression is a threat to an authoritarian regime, this is why perpetrators receive awards, not punishment for oppressing journalists’ rights. This process leads to self-censorship, and journalists stop being carriers of truthful information, which in the end affects society.

Nazeeha Saeed, award-winning Bahraini journalist, who was tortured in police custody

Impunity is a threat to free expression because journalists and people who report the facts on the ground will feel danger, and if no one gets punished for crimes against journalists or others it establishes a systematic impunity culture. Feeling insecure is something bad, it stops people from having a normal life, functioning and expressing themselves.

Endalk Chala, Ethiopian blogger and co-founder of the Zone9 blogging collective (of which six members are currently imprisoned for their writing)

Impunity is a threat for free expression on many levels. In my experience I have seen impunity when it cultivates self-censorship. Let’s take the case of Zone9 bloggers. Since their arrest there are a lot of people who tried to visit them in prison, take a picture of them, attend their trial and tweet about their hearings but all of these have invited very bad reactions from the Ethiopian police.

Some were arrested briefly, others were beaten and it has become impossible to attend the “trial” of the bloggers and journalists. No action was taken by the Ethiopian courts against the bad actions of the police even though the bloggers have contentiously reported the kinds of harassment. As a result, people have stopped tweeting, taking pictures and writing about the bloggers. Apparently, the volume of the tweets and Facebook status updates which comes from Ethiopia has dwindled significantly. People don’t want to risk harassment because of a single tweet or a picture. This self-censorship could be attributed to impunity, which is pervasive in Ethiopia.

Impunity also causes a lack of trust in the Ethiopian judicial system. I don’t trust the independence of the Ethiopian justice system. I have never seen a police man/woman or a government authority being prosecuted for their bad actions against journalists. The Ethiopian government has been prosecuting hundreds of journalists for criminal defamation, terrorism and inciting violence but not a single government person for violating journalists’ rights. This tells you a lot about the compromised justice system of the country.

Andrei Soldatov, Russian investigative journalist and co-founder and editor of Agentura.Ru

Russia is known for its traditions of self-censorship. Despite what the laws say, the rules are explained in a quiet voice in some unmarked cabinets. Sometimes the rules are even not explained, and journalists, editors and owners of media have to constantly guess what is allowed at that moment. Not everyone is allowed to ask directly, so we are all in the game about signals sent by the authorities.

Journalists are beaten and killed in Russia, and this provides plenty of room to send such signals to the journalistic community. You don’t need to explain that investigative reporting in the North Caucasus is not allowed anymore: you just need to turn the investigation of Anna Politkovskaya’s assassination in 2006 into a show trial, where the assassins are duly found guilty, but the question of masterminds is never answered. You could be sure, the signal would be taken correctly.

Fergal Keane, Irish journalist, BBC foreign correspondent and 2003 Index award winner

Impunity allows the enemies of free speech to threaten, torture and kill journalists secure in the knowledge they will never be called to account. I can’t think of a greater threat.

Veran Matic, B92 board of directors chairman and B92 news editor-in-chief

In my 25 years of experience in Serbia, I have been editor-in-chief of a media outlet that was banned on several occasions and I have been arrested.

Impunity directly encourages and expands violence towards journalists. The culture of producing fear is the most efficient form of censorship. One unsolved murder creates space for implementing the next one without any threat for the executioners. In the meantime, the media gets killed/eliminated in the process.

The lack of discontinuity with Slobodan Milosevic’s authoritarian regime had left room for impunity to remain intact.

Less than two years ago, I decided to make a kind of a breakthrough when it comes to impunity. I proposed the establishment of a mixed commission composed of journalists, members of the police and members of the security information agency. We managed to bring the 1999 murder of Slavko Curuvija to a phase where official indictment was brought, along with arrest of all suspects in this murder case. The 2001 murder of our colleague Milan Pantic is also in the final stage of investigation. A 1994 assassination — of Dada Vujasinovic — is being reviewed by the National Forensic Institute from The Hague because local institutions have compromised themselves in this case.

In the same way as impunity restricts freedom of speech, solving of these cases, at least 20 years later, will surely contribute to journalists being encouraged to do their job in the best possible way. Of course, I am not counting here on the new problems with which journalists and media face, and that call for finding new models of financing high quality journalism for the sake of public interest, worldwide.

The team behind Pao-Pao, a Chinese website focusing on internet freedom issues

This year, we have seen a rising number of Chinese journalists, academics and human rights lawyers detained, threatened and arrested simply for speaking out online. While Chinese regulations on freedom of speech need to be closely examined, tech companies also play an important role in the deterioration of freedom of speech in China.

While Chinese tech companies are under the tight control of the Chinese authorities, there exists a culture of impunity in the western tech companies, especially when they are doing business in China. When we worked with our partner GreatFire to launch a FreeWeibo iOS application last year (an app to deliver uncensored content from Weibo, the largest social media platform in China), Apple decided to remove the app from their Chinese iTunes store. The only reason given was that Apple received a request from the Chinese authorities. This June, LinkedIn censored user posts deemed sensitive by the Chinese government on the global level, far beyond Beijing’s censorship requirement, even though LinkedIn does not have servers in China.

It would be the start of the end if these global tech companies start removing content simply because they do not want to upset their business relationships with China. It is crucial to hold these companies accountable for their behaviour. Otherwise it will further erode freedom of expression, not only for China, but also for the whole world.

The International Day to End Impunity was set up in 2011 by free speech network IFEX, of which Index on Censorship is a member, with the aim of demanding accountability and justice on behalf of those “targeted for exercising their right to freedom of expression”.

This article was originally posted on 21 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org. It was updated at 14:09, 24 November to include the response from Pao-Pao.

21 Nov 14 | Ecuador, Magazine, News and features, Politics and Society

Diana Amores’ Twitter account is currently suspended (@Diana_Amores). Is she a troll? Is she sending offensive pictures? No, she’s a translator based in Quito, Ecuador, with a tendency to post sarcastic comments about politics.

Diana is being targeted by Ares Rights, an internet reputation management company based in Barcelona. The trouble started earlier this year when she was being critical about the Ecuadorean government. Ares Rights filed complaints, claiming copyright violations and shut her down.

Why is a Spanish company concerned about what is being said about the Ecuadorean government? If you look at the individual complaints (and we have), Ares Rights has filed them on behalf of, variously, Ecuador’s governing party, Movimiento Alianza País; EcuadorTV (the state-run television station;) and even the president, Rafael Correa. The company has had various Twitter accounts suspended and documentaries pulled from YouTube. They have also targeted Buzzfeed and Chilling Effects, who wrote about Ares Rights specifically.

Is this an attempt by the state to silence critics? You can read the full, in-depth story here, from the last issue of Index on Censorship Magazine.

Diana’s latest Twitter suspension is on account of reports of “violent threats”. This is one of her alleged violent threats (translated from Spanish): “Today I received a notification of censorship from @Twitter and @Aresrights.” She included a screengrab of an email she received from Twitter saying AresRights had raised a copyright complaint. Again, it claimed to be filing this on behalf of Movimiento Alianza País (Correa’s party). This doesn’t prove they are contracted, but neither party have responded to Index’s call for clarification for our recent feature.

On Wednesday, there was an opposition march in Quito. Diana wanted to tweet from it. She couldn’t.

At the march, protesters held up a message to the government: “We are not afraid anymore”. President Correa has been accused of trying to intimidate critics. He has successfully pursued several libel lawsuits against the media since introducing his controversial communications law in 2013.

One of the early targets was a political cartoonist, Bonil. His newspaper, El Universo, was fined $92,000 over one of his cartoons. Now, 11 months on, Bonil is currently responding to a new complaint and fearing an even bigger fine.

You can read Bonil’s story – with a new cartoon by him highlighting the censorship of cartoonists – in the next issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

This article was published on 21 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Nov 14 | Media Freedom, Press Releases, Statements

November 2014 (PDF)

As a UK-based organisation dedicated to the promotion of free speech and elimination of censorship worldwide, Index on Censorship is pleased to have the opportunity to provide feedback on the documents that proposed press regulator IMPRESS has drawn up ahead of its formal launch. Index also made written and oral representations to The Leveson Inquiry on the culture, practice and ethics of the press.

IMPRESS asked specific questions, to which Index has responded below. Our comments should be in no way seen as an endorsement – or indeed – a rejection of IMPRESS.

1. Do these documents meet the criteria set out in the Leveson Report, as distilled in the Royal Charter on Self-Regulation of the Press, for an independent and effective regulator? How might they be improved in this respect?

These documents reflect in large part the criteria set out in the Leveson Report and even more closely the requirements outlined in the Royal Charter on Self-Regulation of the Press, particularly on the important question of redress through swift and transparent complaints and arbitration procedures.

However, Index remains concerned that the independence and efficacy of a regulator will not be guaranteed by seeking recognition from an oversight body established by Royal Charter. A Royal Charter – though arcane – remains a political instrument. Royal Charters are established by Her Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council, the bulk of whom are politicians, including serving members of government. Though we accept that the Recognition Panel is conceived in a way that is intended to demonstrate absolute independence from government control, the establishment of an oversight

body through such an obscure piece of political machinery is not a mechanism likely to inspire the public trust and confidence required by the public. The whiff of undemocratic, non-transparent political involvement in the creation of the regulatory body has tainted it from the outset.

As the Privy Council says on its own website: “…once incorporated by Royal Charter a body surrenders significant aspects of the control of its internal affairs to the Privy Council. Amendments to charters can be made only with the agreement of the Queen in Council, and amendments to the body’s by-laws require the approval of the Council (though not normally of Her Majesty). This effectively means a significant degree of Government regulation of the affairs of the body, and the Privy Council will therefore wish to be satisfied that such regulation accords with public policy.” (our italics)

There is little clear evidence that the Recognition Panel, as currently conceived, would restore public trust in the British press, or indeed behave in a way that would hold a regulator successfully to account, as scandals involving the oversight of other independent regulators, such as the Care Quality Commission, have shown. A study by the Media Standards Trust has shown that more than 70% of the public believe that it is important that a new system of press self-regulation is periodically reviewed by an independent commission, but it is by far from clear that the public believes that this should be a Recognition Panel established by Royal Charter. An opinion poll conducted by Survation in April 2013 found that 67% of those surveyed concurred with a statement that any regulatory system should be set up ‘in a way that does not give politicians the final say if and when changes need to be made’.

In addition, Index remains concerned that, aside from the Royal Charter, other elements of legislation introduced in the wake of the Leveson Report represent a threat to media freedom. One of the most worrying of these is section 42 (3) of the Crime and Courts Act 2013, which sets out that an organisation which does not join a recognised regulator but falls under its remit (through being considered a “relevant publisher”) will potentially become subject to exemplary damages should they end up in court, and could also be forced to pay the costs of their opponents.

There are two principles here that threaten a free press. Firstly, that in effect joining a regulator becomes less than voluntary if you have the threat of punitive damages hanging over your head. Secondly, that those who do not join and therefore feel under threat of exemplary damages will skirt away from controversial subjects and investigative journalism, and opt instead for “safe” stories.

Such measures could be especially punitive for small publishers and news organisations with limited financial means. This has a damaging effect on free expression.

Supporters of this aspect of the act argue that exemplary damages would only apply to “reckless” action by journalists, but it is possible that a court could find that a breach of Article 8 rights to privacy and reputation was by definition “reckless” even when a journalist was pursuing an investigative news story in the public interest.

2. Do these documents (in particular the ‘sunset clause’ in the Mem & Arts) serve to protect the regulator’s independence from potential interference by politicians or civil servants? How might they be improved in this respect?

The memorandum and articles skirt around the issue of whether IMPRESS would seek recognition under the charter although it is made clear in other documents that IMPRESS would seek recognition. For the reasons outlined above, Index believes that IMPRESS should not seek recognition under the Royal Charter and that a robust ethics code, financial independence, and demonstrations of efficacy (i.e. participants shown to be held to account; swift and cheap arbitration) are the only ways in which the independence of the regulator will be truly demonstrated.

3. Do these documents serve to protect the regulator’s independence from potential interference by subscribing publishers? How might they be improved in this respect?

It is unclear from the documents supplied by IMPRESS what precisely the relationship would be between the funding mechanisms for IMPRESS and the regulator itself. The implication of the documents is that the regulator would be funded by participants (as with IPSO) but (unlike IPSO as currently envisaged) these participants would have no further role in setting the agenda for IMPRESS or carrying out its duties.

Complete transparency over the regulator’s funding is vital for its success. The agreement between participants and regulators should state explicitly that the funders can have no role whatsoever in the operations of IMPRESS or in its decision-making. Clear and total separation between the funding of the regulator and the regulator itself is vital to ensure press freedom.

The IMPRESS website identifies a number of current funders of IMPRESS but no details are given outlining the expected cost of running the regulator or the regulator’s financial plans. This raises the question of how the body can ensure it will be adequately funded — and therefore its long-term sustainability — should participants decide, for whatever reason, that they are no longer happy with the decisions being taken by IMPRESS. This should be clarified, along with greater detail on the projected cost of the regulator and its intended sources of income.

One mechanism that could help improve public confidence in the industry as a whole might be to make subscription open to individual journalists. This would mean the public could be assured that the body represents the press as a whole and would help IMPRESS to cover a fuller range of publishers who might be covered by the Crime and Courts Act.

4. At the same time, do these documents serve to give subscribing publishers confidence in the regulator’s operations? How might they be

improved in this respect, without compromising the regulator’s independence from the news industry?

It is unclear from the documents provided by IMPRESS whom it considers to be a likely member. The Crime and Courts Act sets out four cumulative criteria which must be met by a publisher to satisfy the definition of relevant. A publisher must:

. Publish “news-related material” (see below)

. Publish “in the course of a business” (whether or not carried on with a view to profit)

. [Produce material] “written by different authors”, and

. [which is] “subject to editorial control” (over the content of material, presentation

and the decision to publish).

Schedule 15 of the Act exempts publishers including broadcasters, public bodies, charities, micro businesses, and those who publish special interest titles, scientific and academic journals, company news publications, and books. But as English PEN has shown (‘Who joins the regulator: A report on the Crime and Courts Act on publishers’), a number of small publishers may nevertheless be caught in the net and there remains a “dangerous” level of uncertainty about the definition of “relevant”. Index has serious concerns that the implication of this, as detailed above, is a restriction on

investigative and challenging journalism.

5. Do these documents provide clarity about the regulator’s procedures? How might they be improved in this respect?

More clarity in the Procedures document regarding; the internal ombudsman; the complaints handling procedure; and conditions of joining, would be welcome. In its prospectus, IMPRESS states: “The regulator will not receive complaints directly unless or until the internal complaints system has been engaged without the complaint being resolved in an appropriate time.”

6. Do the IMPRESS/CIArb Arbitration Rules serve to give potential litigants in a relevant action confidence in the scheme’s capacity to provide access to justice? How might they be improved in this respect?

Index would suggest that IMPRESS consider the Alternative Dispute Resolution mechanisms outlined in the submission by the Alternative Libel Project, a collaboration between Index on Censorship and English PEN, which include suggestions on Early Neutral Evaluation. Details can be found here.

—

In conclusion, Index welcomes attempts by all the sides of the press to better self-regulate in ways that both protect the independence of the media and the free speech rights of the broader public. However, we remain opposed to the Recognition Panel as established by Royal Charter as the mechanism through which oversight of any regulator should be achieved, and deeply concerned that punitive measures such as exemplary damages negate any notion of a recognised regulator being voluntary.

—

This material can also be found in PDF here.

20 Nov 14 | Ireland, News and features, Politics and Society

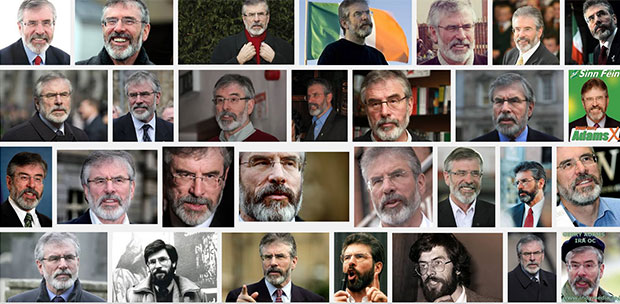

Gerry Adams is the leader of Sinn Féin, the party currently polling higher than any other in Ireland. Last week, Adams, who for many years had the very sound of his voice banned from the airwaves in both Ireland and Britain, due to his connections with the illegal Provisional IRA, told a funny little story at a fundraiser in New York.

Discussing one Irish newspaper’s hostility to his party, Adams told the assembled of how Michael Collins, the Irish War of Independence leader, had dealt with the Irish Independent:

“He went in, sent volunteers in, to the offices, held the editor at gunpoint, and destroyed the entire printing press. That’s what he did. Now I can just see the headline in the Independent tomorrow, I’m obviously not advocating that”, said Adams.

As with much half-remembered Republican mythology, this wasn’t the whole story. As Ian Keneally, author of The Paper Wall: Newspapers and Propaganda in Ireland, 1919-21, related in the Irish Times, the Irish Independent had been broadly sympathetic to the cause of Irish freedom throughout the War of Independence, while deploring individual acts of violence. In the case Adams alluded to, a group of IRA men had indeed entered the Irish Independent offices and threatened the editor, Timothy Harrington, after the paper described a failed IRA ambush as “a deplorable outrage”. The leader of the IRA grouping, Peadar Clancy, said that the newspaper had “endeavoured to misrepresent the sympathies and opinions of the Irish people”. While some damage was done to the Irish Independent’s printing presses, the paper did not shut down.

Ironically for Adams, given his invocation of the fabled Michael Collins, the Irish Independent found itself in deep trouble with British forces for publishing a letter by the IRA leader in December 1920. On that occasion, British “Auxiliaries” entered the newspaper’s offices and literally held a gun to a staff member’s head, warning the paper never to print anything by Collins again. The threat worked.

Historical rigour aside, Adams’s comments obviously didn’t find much favour among journalists. The World Association of Newspapers wrote to Adams calling on him “to retract these comments and to publicly affirm your abhorrence of all forms of violence against journalists”. Adams has refused to do so, citing the hypocrisy of attitudes to the Collins & Co war-of-independence era IRA and the modern (now, we are told, departed) Provisional IRA. In this, he may have a small point, though this is an issue for Irish society at large and not just the newspapers (this cartoon captures that problem neatly).

One could excuse Adams’s allusions as the work of the mind behind his famously quirky, often tongue-in-cheek Twitter account, but there are several background issues that make the whole thing a little uncomfortable.

Firstly, the newspaper group involved has lost two journalists to gunmen in the past 20 years: Veronica Guerin of the Sunday Independent, murdered by gangsters in 1996, and Martin O’Hagan of the Sunday World, shot by loyalist paramilitaries in 2001. Jokes about threats to the Independent News & Media journalists carry that baggage, even if unintended.

Secondly, Adams and his party are currently under scrutiny over an alleged IRA sexual abuse cover up. A woman named Maria Cahill – a relative of Provisional IRA founder Joe Cahill – claims that she was raped by an IRA member, and that the organisation subsequently attempted to cover up the crime. Cahill claims she raised the issue directly with Adams (who, it should be stated for the record, says he has never been a member of the IRA, but nonetheless is viewed as the leader of that particular strand of Irish republicanism), but that justice was not done. Adams’s has already faced criticism for the alleged cover up of his brother Liam’s paedophilic assaults on family members.

Thirdly, Ireland is a country on edge at the moment. The Fine Gael/Labour coalition government’s disastrous handling of proposed water metering and charges has led to previously rarely seen nationwide protests. Having almost cast the previously dominant Fianna Fáil party into oblivion in 2011, Irish voters had hoped they could put faith in a new government. But now, once again, they feel lied to by politicians who do not seem to have the wishes of the population at heart. The perception is that the new water metering system is just another assault on people who have suffered enough after years of boom, bust and bank bailouts.

Into this already toxic mix comes media mogul Denis O’Brien, owner of, among other outlets, the Irish Independent. It is widely believed that O’Brien is supportive of the new watering metering system as Irish Water will eventually be privatised, and he will buy it. O’Brien has a stake in Siteserv, the company contracted to install water meters.

It is not a huge leap to imagine that O’Brien’s papers may be enthusiastic about water charges, and perhaps unsympathetic to protesters. And it’s not difficult to imagine anger being turned against Independent group journalists. After pictures of a brick being thrown at a Garda [police] car during a water protest in Dublin last week were published by the Sunday Independent, many online claimed the image had been photoshopped by the mendacious “Sindo” . This was clearly untrue, but the rumours demonstrated the distrust of institutions, including the press, that now permeates Irish society, and from which upstart Sinn Fein stands most to gain. Former Sinn Féin publicity officer Danny Morrison subsequently tweeted the address of Independent Newspapers, along with a picture of a wall missing a brick. Was he adding to the conspiracy theory? Or was he suggesting violent action against the Independent, in classic I-know-where-you-live style? See how easily the close-up nature of Irish media, politics and public life can set the mind racing?

The government has now proposed new water measures, which it hopes will quell the unrest. But the anti-press, anti-politics rhetoric may have gone too far for that, and in the run up to the centenary of Ireland’s “revolutionary period” of 1916-1923, when romantic rebellion ruled all, little will be gained by any party attempting to present itself as the voice of a reasonable settlement.

This article was posted on 20 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Nov 14 | Bahrain, News and features

Update: Bahrain will hold parliamentary elections on Saturday. Opposition groups including Al-Wefaq will boycott the vote, as leading member Abdul-Jalil Khalil told the Associated Press “”These elections are destined to fail because the government is incapable of addressing the political crisis. The next parliament is going to be powerless and unrepresentative.”

In October, a Bahraini court suspended all Al-Wefaq activities for three months, including hosting rallies or press conferences. Just weeks before US State Department official Tom Malinowski was ordered to leave Bahrain after meeting with Al-Wefaq leaders.

In the last elections, held in 2010, before Arab Spring protests, the Bahraini governement claimed 67 percent voter turnout. Many doubt whether turnout will be as great to help narrow down the 419 candidates.

Bahrain human rights activist Zainab Al-Khawaja was released from prison on Wednesday after spending five weeks imprisoned. Al-Khawaja, who is more than eight months pregnant, must return to court on 4 and 9 December for her sentencing.

Al-Khawaja was arrested on 14 October after she ripped a picture of the king in court, where she faced charges for insulting the king.

“I am the daughter of a proud and free man,” Al-Khawaja said in court. “My mother brought me into this world free, and I will give birth to a free baby boy even if it is inside our prisons. It is my right, and my responsibility as a free person, to protest against oppression and oppressors.”

Maryam Al-Khawaja, Zainab’s sister, spoke with Index last month, urging the UK to speak out against human rights violations in Bahrain.

“It isn’t that the people who are being arrested will stop doing what they do, because I don’t think that they will and I think the past four years have been evidence to that,” Maryam said. “My worry is that those people become voiceless. Those people become people who are not heard or seen or cared about. Because that’s when the Bahraini government will find the platform to do whatever they want to do to those people. ”

Maryam also spent time in prison recently and will return to court on 1 December. Their father remains imprisoned.

Nabeel Rajab, President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR), was recently released on bail after his 1 October arrest. Rajab was imprisoned for “denigrating government institutions” on Twitter.

The GCHR released a statement calling for Rajab’s charges to be dropped.

“Bahrain has made international commitments to protect freedom of expression, yet it continues to jail human rights defenders who are simply exercising their right to free speech, whether via twitter or while speaking internationally about Bahrain’s problems,” said Khalid Ibraham, co-director of GCHR.

Rajab must return to court on 20 January 2015 and may not leave Bahrain until then.

Rajab was released in May after spending two years in prison for “making offensive tweets and taking part in illegal protests.”

This article was originally posted on 20 Nov 2014 indexoncensorship.org and was updated on 21 Nov 2014.

19 Nov 14 | Africa, Central African Republic, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Nations

Bambari’s last functioning radio station was looted on 7 July. (Photo: Jonathan Pedneault / Internews)

The arrival of MINUSCA, a United Nations’ peacekeeping force, on 15 September briefly pushed the continuing crisis in Central African Republic to break back into international headlines. This conflict, which has claimed thousands of lives since the Séléka coup in March 2013, is repeatedly referred to as a “forgotten crisis”, “neglected tragedy” and “the worst crisis you’ve never heard of”.

In fact, with almost half the population of 4.6 million in need of emergency aid, the country is caught up in the worst humanitarian and political crisis of its history. In the short months since the Blue Helmets arrived in Bangui, violent clashes have killed at least 12, wounded many more and further complicated already strained relief operations. Since almost all aid passes through the capital, violence there cuts off assistance for the rest of the country. Crime is rampant, with freedom of movement severely restricted by both security concerns and checkpoint bribes.

As the fighting flared up once again, Mahruhk Hasan, head of monitoring and evaluation for Internews, pointed out on Twitter in October that a quick Google search provided only seven stories in the international, English-speaking media.

While frustration over the lack of international media attention is legitimate and necessary, it is crucial to consider what is happening to the media at a local level. Disturbingly, the scant information readers in the West receive may often be more than the residents get in the country itself. Condemning the lack of global media coverage overlooks the crisis enveloping the Central African Republic’s media. The bloodshed has led to an information blackout, with local radio stations and newspapers often being casualties of the conflict.

In a country twice the size of the UK, with only a few hundred kilometres of tarmac, poor mobile connectivity and a largely rural population heavily reliant on radio, the national broadcaster has stopped airing with no sign of return. Many other radio stations have been looted, with most going mute at least 18 months ago. As of late July 2014, there were 15 operational radio stations across the country – but 14 further stations have fallen silent, including the single station in northern Vakaga province, which is the area with the highest number of internally displaced people. A recent report by International Media Support found “Central Africans are living in complete darkness as they have no access to information.”

This “darkness” serves to exacerbate a dangerous culture of rumours, with serious implications for further loss of life. MINUSCA’s deployment is phased, and will not reach peak until January 2015. In an already dicey security context, where the protection of NGO staff and aid workers is severely compromised, it is proving logistically impossible to provide journalists with protection.

The journalistic profession has never been particularly stable in CAR, affected by poor and inconsistently paid salaries, as well as corruption and lack of resources. Since the conflict began, pressure and violence have had serious effects on self-censorship.

Reporters Without Borders recently provided a summary of the persecution of journalists during the three months ending 31 May 2014, including the case of Elisabeth Blanche Olofio, a radio journalist killed in connection with her work after being accused of having “a sharp tongue”.

Two other journalists, Désiré Luc Sayenga and René Padou, died of the injuries they received in a brutal attack in unclear circumstances. There have also been numerous incidents of harassment and telephone threats, as well as journalists being summoned by judicial authorities before fleeing the country. CAR had the biggest fall of any country in the 2014 Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index, dropping 43 places to 109 out of 180 countries.

In conflict situations, discussion of censorship often centres on whether such measures are justified in keeping citizens safe, and whether or not “national security” is simply a convenient excuse for governments to silence their critics. But in the case of Central African Republic, the state is still far too weak to exert any kind of strong censorship.

Instead, reporting remains limited and compromised due to fear. This level of suffering, in a crisis so determined by deep-set prejudices, has a clear effect on the professionalism and impartiality of journalists. As Jonathan Pedneault, Conflict-Sensitive Journalism Trainer with Internews in CAR, highlights: “Discourses are so polarised in CAR, and the problem is that everyone thinks they have the true story.”

This isn’t to suggest that journalists in Bangui aren’t subject to top-down censorship. Pedneault references a case in late October where journalists were threatened with a 25,000,000 CFA franc (£30491.25) fine when they remained silent after being summoned by the High Council for Transitional Communications. In their own words, the council were questioning the journalists’ credibility and editorial line in a crisis situation when they ought “to censor some things”.

Internews have been working in Central African Republic since 2010, supporting local media and providing in-situ training and mentoring to journalists, with a special focus on conflict-sensitive reporting. They are only too aware of the extreme psychological impact of the recent conflict on journalists, understanding that they are subject to the fear and trauma affecting the entirety of the population. Many journalists express “concerns over personal safety after they report”, particularly outside Bangui, Pedneault said

Internews is working closely with the local Association of Journalists for Human Rights (RJDH), giving reporters the space to discuss and better understand the root causes of the conflict, as well as recognising their own personal biases. Pedneault underlines that the conflict has meant “the judicial system has been destroyed”, which fosters a sense of insecurity, particularly in a country with an armed population able to “take bold action”.

Pedneault explained that the weak state means self-censorship is an issue tied mostly to the personality of the journalists and their own fears: “I’d not consider it political censorship, but attuned to each journalist.” These fears, tragically, are not unfounded.

On 8 October, the pregnant aunt of one of the RJDH journalists was abducted; the following day the journalist received an anonymous call informing her that her aunt’s disembowelled body could be found in the PK5 district. It is hard to say whether this tragedy is directly linked to her work as a journalist, or whether it is simply a terrible facet of the violence engulfing everyone in Central African Republic.

In Bambari, a flashpoint for the conflict where 71 per cent of the population is displaced, the two remaining radio stations were looted in early July and journalists have not returned to work, fearing for their lives. This took place amid accusations that the broadcasts were biased and encouraging violence.

To better understand the media landscape in CAR, as well as the prevalence of hate speech, Internews has been conducting media monitoring, and in Bambari have begun creating an interfaith radio station in an attempt to foster community cohesion alongside improved communication. As well as working closely with RJDH in Bangui, supporting them to produce a daily radio show in French and Sango and between 5-10 articles per day, Internews is supporting the return of local media in more remote areas.

Pedneault works as a roving trainer, travelling to rural areas and working embedded in the newsroom, supporting the journalists in their own environment. Internews is fostering a network of voluntary community and professional correspondents and developing a cadre of writers and broadcasters who can be an engine for change.

Hasan underlines that Internews and RJDH have been open to the use of pseudonyms when broadcasting, offering a greater sense of security and encouraging individuals to speak out. The coverage maps produced by Internews are also allowing humanitarian actors to link with local media and facilitate the dissemination of lifesaving information.

Jacobo Quintanilla, Director of Humanitarian Communications Programmes, said that with shortwave radio, you compromise on sound quality but maximise outreach: “You can reach refugees living in camps in Chad.” Hasan highlighted Internews’ plans to distribute wind-up radios for use by internally displaced populations, further extending the spread of information.

“Some of these radio stations are literally lifelines,” Quintanilla said.

In Central African Republic, information is aid – and this is true not only in terms of facilitating immediate humanitarian relief, but also for longer term peace-building. When confronting the huge task of restoring mutual respect in a country torn apart by inter-community violence, journalists who are unafraid, uncensored and impartial can provide a platform for reconciliation.

This article was posted on 19 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

18 Nov 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News and features

(Photo: Index on Censorship

Organisations and individuals from across Europe gathered in front of Azerbaijani embassies on Monday to call for the release of political prisoners and demand Azerbaijan ends its crackdown on civil society.

Index on Censorship, joined by Platform London among others, held a demonstration outside the embassy of Azerbaijan, lighting near 100 candles, one for each political prisoner currently jailed on trumped up charges.

Azerbaijan’s National Revival Day is on 17 November. On this day in 1988, people started demonstrating in Azadliq (Freedom) Square, and the protest grew into a national movement that led to the declaration of national independence from the Soviet Union. Today, 26 years later, the people of Azerbaijan cannot even gather in Freedom Square to ask for the release of political prisoners. Freedom of expression and assembly are repressed, and those who dare speaking up face heavy consequences.

Protesters held a vigil in front of the Azerbaijan embassy in London to call for the release for political prisoners in the country. (Photo: Index on Censorship)

In the past six months, as Azerbaijan chaired the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers, authorities unleashed an unprecedented crackdown on civil society, including the imprisonment of human rights defenders and political activists. Others have been forced into hiding.

Those imprisoned during Azerbaijan’s chairmanship (14 May – 13 November 2014) include:

- Anar Mammadli, election monitor and this year’s Václav Havel Human Rights Prize recipient

- Leyla Yunus, justice advocate who was awarded the French Legion of Honour in 2013, and her husband Arif Yunus,

- Rasul Jafarov, campaigner who has criticised Azerbaijan at the Council of Europe and, together with Leyla Yunus, compiled a list of political prisoners in Azerbaijan,

- Intigam Aliyev, human rights lawyer who has criticised Azerbaijan at the Council of Europe.

As the situation continues to deteriorate, Azerbaijan is getting ready to host the first European Olympics in summer 2015, an event designed to whitewash the repressive regime’s record.

Platform London will be holding other demonstrations at 5pm everyday this week.

- Tuesday 18 November BP’s HQ – 1 St James’ Sq – 5pm

- Wednesday 19 November – Uk Foreign and Commonwealth Office on King Charles Street – 5pm

- Thursday 20 November – the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 1 Exchange Square (by Liverpool st) – 5pm

- Friday 21 November – the International Olympic Committee – 60 Charlotte Street

17 Nov 14 | Awards, News and features, Russia

Former naval officer and journalist Grigory Pasko risked everything to uncover environmental degradation committed by the Russian Navy. (Photo: robertamsterdam.com)

In the 1990s, Grigory Pasko, a former naval officer and journalist, reported that Russia’s navy was dumping nuclear waste in the Sea of Japan (East Sea). After a series of articles exposing the environmental crimes, Russian federal security service agents arrested him in 1997, on charges of espionage and abuse of his official power. He was tried several times and eventually sentenced in December 2001 to four years of imprisonment for espionage. He was finally released in January 2003.

Pasko is one of many journalists who has been targeted by the Russian government. He says that freedom of speech and media in the country today, is not that different from when he was named International Whistleblower of the Year at the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards 13 years ago.

“It is just the same blatant rule by the security services, the same totalitarianism and lack of democratic institutions,” Pasko told Index in an email exchange.

Investigative journalists, in particular, are scarce in the current Russian environment, though the 1990 Law on the Mass Media [1991] states that journalists are allowed to carry on investigations. Article 29 of the Russian Constitution bans censorship altogether. However, under Vladimir Putin’s administration, Pasko said that press freedom and new, economically independent media have disappeared in favor of blatant propaganda.

Nominations for the 2015 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards close on 20 Nov.

Who will you nominate? A journalist? A digital activist? A campaigning organisation? An artist? Or all four?

“Investigative journalism barely exists as a genre in Russia,” Pasko said. “Journalists in our country are killed and put in prison.”

In March 2011, Pasko and his colleagues, Galina Sidorova and Igor Korolkov, established the Foundation for Investigative Journalism as a way to help professional and citizen journalists alike, as well as to create open discussion and respect for the law. It maintains “zero tolerance towards corruption in all forms”.

“Our goal is to help those who pursue this form of journalism,” Pasko said. “So far we have held schools in investigative journalism for journalists and bloggers in many towns throughout Russia. Unfortunately, funds from our sponsors limit us to holding only three such schools a year.”

Pasko said the foundation aims to teach journalists “to be free. To obey the law. To help the democratic development of journalism in Russia. To know how to use the rights they have been given by the constitution and the law. Not to be afraid.”

In a bleak time for journalists and a free media, Pasko said there is always hope for a brighter, freer future.

“The Russian public will feel a need for the truth, just as it has a need to drink fresh not stagnant water,” Pasko said. “Then society will have a need for independent free journalists. Our task and our goal meanwhile are not to let them disappear and keep the genre of investigative journalism alive.”

This article was posted on 17 Nov 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

14 Nov 14 | Europe and Central Asia, Events, News and features, United Kingdom

(Photo: Melody Patry)

Should there ever be censorship of the arts was the subject of an Index/Bush Theatre debate, held last night. The event was provoked by the cancellation of Exhibit B in London, and Israeli play The City at this year’s Edinburgh Festival Fringe as well as controversy around this year’s Jewish Film Festival, all in the past few months.

Taking part in the debate were, among others: Stella Odunlami, artist and a cast member of Exhibit B; Zita Holbourne, artist, activist and co-organiser of the campaign to boycott the show; and Arik Eshet, artistic director of Incubator Theatre, which produced The City.

An Exhibit B performer Stella Odunlami told the audience: “We, a group of intelligent and informed actors and performers, have been censored and silenced by protestors, who truly have an ill-informed and misguided perspective of this significant and informative piece of work.

We are appalled, outraged, angry…extremely angry as artists, as human beings. We cannot believe that this is London in 2014. We are appalled that Exhibit B has been cancelled because of the actions of some of the demonstrators.”

Protester Zita Holbourne put her point of view as a poem, she said: “We said to them, Barbican please take that down, 2014 and you want to put black people in a cage? Then telling us you don’t understand our outrage!”

Read their full statements, made to the audience, below.

Stella Odunlami read the statement from the London cast of Exhibit B

It is with utter disappointment that we write these words.

Exhibit B is an important work that has given us an education into the lives of other human beings. We believe everybody has the right to their specific story being told, and this work provided that platform, through the medium of art – living and breathing. It is a shame that these stories will no longer be heard, seen, nor felt. An even greater shame that those who were open and brave enough to purchase a ticket, have now been robbed of that experience.

Exhibit B afforded us the opportunity to explore and engage with our past, while reminding and reawakening us to its impact on the present.

To the 23,000 petitioners who complained that Exhibit B objectified human beings – you missed the point.

This is the 21st Century and we believe that everyone has a choice, a right, an entitlement, to do or say whatever they deem to be right for them. We can accept someone seeing the piece and not liking it-that’s fine. What we cannot accept about the events of Tuesday evening and the subsequent cancellation of Exhibit B, is the physical action that was taken outside of the Vaults, by a minority of the demonstrators who would not even entertain the thought of seeing the piece.

We, a group of intelligent and informed actors and performers, have been censored and silenced by protestors, who truly have an ill-informed and misguided perspective of this significant and informative piece of work.

We are appalled, outraged, angry…extremely angry as artists, as human beings. We cannot believe that this is London in 2014. We are appalled that Exhibit B has been cancelled because of the actions of some of the demonstrators.

We are artists who, after thoughtful and careful deliberation, decide what projects we want to work on. Grown men and women who decided that our contribution to Exhibit B would be worthwhile and important. Who, on Tuesday, were told, by way of the protestor’s force, that we couldn’t make creative and life decisions for ourselves.

That complete strangers knew what was best for us.

For all of us.

Our voices and ideas were deemed not worthy of being shared with the world. This is exactly what Exhibit B is about: we want to denounce oppression, racism and bigotry. We want to denounce actions like this. And the fact that this is still happening in London in 2014, proves even more why this piece is necessary.

The anger and vitriol and hysteria which the protestors have and continue to level at the company of Exhibit B, astounds us.

It doesn’t feel rational. It doesn’ t feel measured. There simply has not been room for an exchange of ideas.

There’s such vulnerability in holding a mirror up to humanity. No one wants to see a representation of themselves oppressed, but it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t look.

We welcome protest, but surely it’s best to have as much information beforehand, so your opinion is truly informed. Surely as a protestor, you have a duty to ensure your ‘peaceful protest’ really is peaceful. And, surely your right to protest should not impact another person’s freedom of thought and speech.

We are actors and performers who believe that art should be meaningful. Challenging. Provoking.

Not only for us, as participating collaborators in the work, but also for the audience who witness the work.

This project afforded us the opportunity to be the most vulnerable, most on display, silently engaging and being engaged, while exploring themes around other, sex, race, and gender.

Exhibit B was created with love and sensitivity. We are intelligent creatives who made a brave choice to be part of a thought provoking piece of work. As Londoners, we are embarrassed that this has happened in our city, as the show has already been seen by 25,000 people from all over the world, and will continue to tour.

We would like to thank the Barbican for their immense support and Brett Bailey for his inspired work.

Zita Holbourne read Prejudice, Privilege, Power: A Poem for the Barbican (listen to it here)

Barbican announced a human zoo in town

We said to them, Barbican please take that down

2014 and you want to put black people in a cage?

Then telling us you don’t understand our outrage!

Strapped to plane seats, placed in iron masks

And nobody in a whole arts institution thought to ask

Our views before taking a decision to host

Then you have the bare faced audacity to boast

That you’ve placed black people in a human zoo

Going around talking about the good it can do

In challenging racist attitudes and views

But to listen to our concerns you refuse

Shackles and cages at £20 per ticket

But you don’t get why we organised a picket

We don’t need to see a black woman shackled to a bed

To know that racism is rearing its ugly head

We’re forced to battle daily with modern day enslavement

Power and privilege versus our self-empowerment

You are arrogant telling those of us that live with racism every day

What is or is not racist, like we don’t have a say

Let’s make clear that a boycott campaign is not censorship

For your actions and failures you must take ownership

We don’t need a lecture on what it is to be banned

We’re treated like third class citizens in this land

Blocked by institutions, so take a moment, pause

Think about the anger and pain you cause

By insulting our ancestors, our histories

Adding insult to our multiple injuries

If anything is censored it’s the art we produce

Rejected repeatedly by art institutions that refuse

To acknowledge our stories told by us through art

We’ve never had a level playing field from the start

We have a legitimate right to protest

It’s disingenuous of you to suggest

That our demonstration was aggressive

When it was simply passionate and expressive

Using the very arts that you claim to stand for

To demonstrate our strength of feeling outside the door

We made music, danced, lifted our voices in song

Displayed placards that had our beautiful art on

Yet you state that we were extreme and threatening

In contrast, press there say we were peaceful and welcoming

Police confirm there was no damage, injury or arrest

So perhaps it’s you trying to censor our right to protest

Their singing was threatening is what the headlines say

Brandishing placards and drums that barred the way

You accuse us of blocking freedom of expression

But then you call our expression aggression!

What does this say about you as a leading arts institution?

When you resort to this vicious persecution

Barbican you are cowardly and insincere

Resorting to this malicious smear

You simply confirm what we said from the start

You are defending racism in the name of art

When prejudice, privilege and power are combined

Institutional racism becomes clearly defined.

Arik Eshet, Artistic Director of Incubator Theatre, spoke via Skype about the cancellation of The City at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival

The Index/Bush Theatre debate was part of the RADAR Festival.

This article was posted on 14 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Nov 14 | Index Reports

Ahead of tonight’s event The Artist and The Censor, we’re reposting our 2011 study about the policing of free expression.

The policing of freedom of expression is the story within the story within the story in this case study. In 2004, Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti (Dishonour) was cancelled after demonstrations against it turned violent and its staging was deemed a threat to public order. Her subsequent play Behud (Beyond Belief) is a response to these events, exploring the tensions between public order and freedom of expression. The dialogue between the theatre and the police in the lead up to the premiere of Behud in 2010 is a principle feature of this case study. Julia Farrington is an associate arts producer at Index on Censorship

Download report here

Beyond Belief COMPILED v5

13 Nov 14 | Draw the Line, Events

The general elections in the UK next May means that the topic of voting and who should be able to vote is under scrutiny, and students at Lilian Baylis Technology School in south London found that there were few clear cut answers.

Index visited the 6th form of Lilian Baylis yesterday to host our latest Draw the Line workshop where we asked the student to examine the question “Are voting restrictions a free speech violation?” in a number of ways. The discussion ranged from the issue of 16 year olds and prisoners voting in the UK, to voting restrictions in different countries including gender, age, level of education, military and mental disability.

![IMG_0965[1]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_09651-1024x768.jpg)

The session concluded in a debate on whether 16 year olds be allowed to vote. The group in agreement pointed out that at 16 you are able to join the army and therefore die for your country, but have no way of directing its political activity. They also argued that although 16 and 17 years old can’t vote now, the outcome of the next election will affect them when they are 18 and for the following few years. As one participant said, tuition fees went up after the 2011 general election, but the 16 year olds who were later affected by this change had no say in it.

The team who disagreed highlighted the fact that 16 year olds are not deemed responsible enough to buy alcohol, see certain films or buy certain video games so they are not responsible enough to vote. They also suggested that many 16 year olds don’t understand politics and therefore shouldn’t be able to take part in the political system.

![IMG_0966[1]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_09661-1024x768.jpg)

Ultimately, however, both groups agreed they should get the chance to have their say who will control their future.

If you would like to get involved you can follow the debate on our Draw the Line discussion page and tweet your own thought using #IndexDrawtheLine.

This article was posted on 13 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![IMG_0965[1]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_09651-1024x768.jpg)

![IMG_0966[1]](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IMG_09661-1024x768.jpg)