06 Nov 14 | News and features, Politics and Society

![People taking part in the funeral procession of Lasantha Wickrematunge (By Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Lasantha_Wickrematunge_funeral_banners_1.jpg)

People taking part in the funeral procession of murdered journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge (Photo by: Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

This would be no defence for Lasantha. President Mahinda Rajapaksa repeatedly referred to him as a “terrorist journalist” and “Kotiyek” (a Tiger).

According to exiled journalist Uvindu Kurukulasuriya, shortly before Lasantha was killed, the president offered to buy the Sunday Leader, with the intention of muting its voice. Lasantha declined the generous offer. On 8 January 2009, he was shot dead.

Days later, an astonishing editorial, written by Lasantha before his death, appeared in the Sunday Leader, and subsequently in newspapers throughout the world. After describing his pride in the Sunday Leader’s journalism, Wickrematunge wrote chillingly: “When finally I am killed, it will be the government that kills me.”

Lasantha’s murder was shocking. As was the murder of Hrant Dink, the Armenian editor who “insulted Turkishness” by daring to speak of the genocide of his people; as was the murder of Anastasia Barburova, the young Novaya Gazeta reporter who investigated the Russian far right; as was the murder of Martin O’Hagan, who took on the criminality of Northern Ireland’s loyalist gangs. As were the murders of the dozens of Filipino journalists killed in the Maguindanao massacre in 2009, too numerous to name, caught up in a ruthless turf war.

Then there are the reporters killed in war zones. The conflict in Syria has been a killing field for journalists. Where once the media were seen as protected, even potential allies, now they are seen as targets. The killings of Steven Sotloff and James Foley by ISIS in Iraq brought back memories of the beheading of Daniel Pearl in Pakistan in 2002. As Joel Simon of Committee to Protect Journalists relates in his forthcoming book, the New Censorship, that crime marked a turning point. In the Pearl case, even Osama bin Laden, who viewed the media as a potential tool in his global war, was shocked by the tactic employed by his lieutenant Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who claimed to have carried out the murder himself. From that point on, journalists were not just fair game, but trophies.

As money is drained from news, many organisations choose not to send correspondents to areas where reporters are needed most. Too dangerous, too expensive. As a result, freelancers, local journalists and fixers take ever greater risks. Under-resourced, undersupported and out on a limb, they are picked off.

Regional journalists covering tough domestic beats are easy prey. In Mexico, drug cartels boast of their ability to murder reporters. In Burma, the army kills a reporter who dares report its activities.

The numbers are horrifying: over 1,000 media workers have been killed because of their work since 1992.

Every single time, the message is sent: don’t get involved; don’t ask questions; don’t do your job. No journalism here. No inconvenient truths, no dissenting voices.

With rare exceptions, those responsible for these crimes act with impunity. Sometimes, as in the case of Anna Politkovskaya, outspoken on war crimes in Chechnya, the man who pulled the trigger is traced but those who gave the orders remain untouched. In over 90 per cent of cases of attacks on journalists, there are no convictions.

There is no greater infringement of human rights than to deliberately take an innocent life. The killing of a journalist also signals contempt for the concept of free expression as a right. As the United Nation’s Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, states, violent attacks on journalists and free expression do not happen in a vacuum: “[T]he existence of laws that curtail freedom of expression (e.g. overly restrictive defamation laws), must be addressed. The media industry also must deal with low wages and improving journalistic skills. To whatever extent possible, the public must be made aware of these challenges in the public and private spheres and the consequences from a failure to act.”

In that famous final editorial, Lasantha Wickrematunge wrote: “In the course of the last few years, the independent media have increasingly come under attack. Electronic and print institutions have been burned, bombed, sealed and coerced. Countless journalists have been harassed, threatened and killed. It has been my honour to belong to all those categories.”

Like many journalists, Lasantha prided himself on bravery: there is no higher compliment in the profession than to call a colleague “courageous”.

But there is a danger in this that we create martyrs: that we become enamoured of the idea that a good journalist should die for the cause. That persecution and suffering are marks of valour.

They are not. Journalism should be intrepid, of course, but we shouldn’t accept the idea that intrepid journalism comes with a price. Journalism, the exercise of free expression, is a basic right both for practitioners and for the readers, viewers and listeners who benifit from it. They should be able to practice this right without fear of persecution from states, criminals or terrorists. If they are to suffer, their oppressors must face justice.

Correction 10:02, 10 November: An earlier version of this article stated that a government minister offered to buy the Sunday Leader.

Index on Censorship is mapping harassment and violence against journalists across the European Union and candidate countries at mediafreedom.ushahidi.com.

This article was posted on 6 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

06 Nov 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

Two lawyers representing Azerbaijani human rights activist Leyla Yunus’s have been dismissed from her case. Javad Javaldi announced his suspension on 29 October, followed by Khalid Bagirov on 5 November. This comes as Azerbaijan’s ambassador to the United Kingdom says the government is “deeply committed” to strengthening its cooperation with the country’s civil society.

The prosecutor general’s office has not provided explanations for the suspensions. They have also prevented Bagirov from meeting with his client Rasul Jafarov, another prominent Azerbaijani human rights activist currently imprisoned.

The lawyers’ dismissal comes less than two weeks after Yunus said she had been denied access to her lawyers. In late September, her lawyers expressed concern at being unable to meet with Yunus in person or speak on the phone with her, saying they were concerned about her physical wellbeing. She has reportedly been beaten by both guards and her cellmate and denied medical attention.

The court has also reportedly extended Yunus’s detention until 28 February. She was initially arrested on July 30 with her husband, Arif, who recently had his pretrial detention extended until 5 March. The two are charged with high treason, spying for Armenia, illegal business activities, document forgery and fraud.

Both detention extensions go against calls from the European Parliament to Azerbaijan to release political prisoners and reform human rights. Last month the European Union praised President Ilham Aliyev when he announced he would release 80 prisoners, including some human rights activists.

Thorbjørn Jagland, secretary general of the Council of Europe and chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, wrote on Monday that Azerbaijan has been “repeatedly warned…over its poor human rights record”.

In a response to Jagland, Ambassador Tahir Taghizadeh wrote in a letter in The Guardian on Thursday that his country has “come a long way in strengthening democracy and human rights over the last 23 years.” He added that “there still exists a long way to go,” and the government looks forward to working with civil society to resolve “human rights issues”.

This article was originally posted on 6 November at indexoncensorship.org

05 Nov 14 | Guest Post, India, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Novelist Jaspreet Singh’s latest novel Helium explores the far-reaching impact of November 1984.

That November is a memory of fire. I saw a burned book, first time in my life. That November my sister’s school was partly reduced to ashes. My entire family survived one of the darkest moments in recent Indian history.

Only a few days before, still recovering from jaundice, I had walked faster than usual to my own school in South Delhi. Around mid-day, we were in the biology lab, dissecting. A strong odour of chloroform filled the laboratory. That is when our biology teacher cancelled the class and walked to my bench and put an arm around my shoulder. You walk carefully all the way back home, she said.

I made it home. But a couple of days later, a mob passed by our block, attacking Sikh citizens. We were the lucky ones. We were able to take refuge in a courageous neighbour’s house.

“Those who survived are not true witnesses.” The Italian writer Primo Levi’s insight into mass violence in Europe is also valid for Delhi and other cities across India.

Only the dead are true witnesses. But the living have come to know a lot. That November 1984, India’s ruling Congress Party used state-controlled radio, television and the dreaded police force to conduct a seamless genocidal pogrom. After Indira Gandhi’s assassination, her son Rajiv Gandhi succeeded her as prime minister and enabled the carnage. Nothing was spontaneous. Cabinet ministers and members of parliament hired and directed mobs to burn to death as many Sikhs as possible. Women were brutally gang-raped. Across India.

Days later, Rajiv Gandhi, justified the violence. Instead of being denounced, he led his party to a landslide victory in parliamentary elections that year, and rewarded several perpetrators by making them cabinet ministers.

Three decades later, not a single prominent politician, cabinet minister, bureaucrat, judge or high-ranking police officer has been brought to justice. (No full and independent inquiry was ever conducted.)

To this day the Indian Parliament has not condemned the anti-Sikh pogrom. The event is wrongfully referred to as “riots”. In vain one looks for hope within society, but it seems the depths of horror and suffering do not disturb the inner life of the nation. A huge crime against humanity has been reduced to a “Sikh issue.” As recently as this year, Rajiv Gandhi’s son, Rahul, tried to defend the indefensible, denying the criminal culpability of his late father.

As much as the Congress party would like to forget, every November there is an anniversary, and the ghosts of 1984 return. The new ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Narendra Modi, selectively invokes 1984 for its own perverse reasons. (This party was responsible for the 2002 Gujarat violence, a pogrom it would like to forget).

To date, the Modi government has taken no steps to provide justice to the victims of the pogrom in 1984.

India’s “democracy” has failed the victims and survivors extraordinarily for the last 30 years. Justice Ranganath Misra, a sitting supreme court judge, the first one to investigate the 1984 carnage went out of the way to suppress truth and to shield and absolve senior Congress party leaders. For his sinister services the party appointed him a member of the upper house of parliament and made him the first chairman of National Human Rights Commission of India. His report had caused a real outrage. Likewise Justice Nanavati’s 2005 report led to massive demonstrations by thousands of people still processing complicated grief and trauma.

For several years now it was unclear whether the international community was aware of the enormity of November 1984. But in 2011 Wikileaks revealed a slice of what the US government has known for a while: “…Congress party leaders competed with one another to see which wards would shed more Sikh blood.”

A pogrom is a wound on the psyche of the entire collective and without justice, mourning and reconciliation, mass-violence often recurs. It is time the United Nations and the country’s major trade partners start playing a prominent role to make India acknowledge the grand crime (committed against its own citizens) and reform its dangerously dysfunctional criminal justice system.

This essay was posted on Nov 5 2014 at indexoncensorship.org with permission of the author

05 Nov 14 | Draw the Line, Young Writers / Artists Programme

In response to this month’s Draw the Line question — “Do laws restrict or protect free speech?” — members of our youth advisory board discuss the different ways laws impact free expression in their home countries.

Margot Tudor talking about UK

Alice Olsson on Sweden

Sophie Armour on the UK

This article was posted on November 01, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

04 Nov 14 | Belarus, Campaigns, Statements

Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Republic of Belarus

to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Republic of Belarus

to Ireland with concurrent accreditation

Mr. Sergei Aleinik

6 Kensington Court, London W8 5DL

3 November 2014

APPEAL

Dear Mr. Aleinik,

Index on Censorship is alarmed by the news that a well-known human rights defender, Elena Tonkacheva, has had her permit to reside in Belarus canceled and may be deported from the country.

Elena Tonkacheva, Chairperson of the Board of the Legal Transformation Center, although being a citizen of the Russian Federation has permanently resided in Belarus since 1985, and for years has been engaged in educational, analytical and research work in the field of human rights. Ms Tonkacheva is a highly qualified expert in law and human rights; the organisation headed by her is one of the leading human rights NGOs in Belarus.

On 30 October 2014, Ms Tonkacheva was notified about the cancelation of her residence permit and on 5 November 2014 a decision will be made as to whether she is to be deported from Belarus. The formal reason for that are administrative breaches (insignificantly exceeding speed limit when driving).

However, the disproportionate measures used by the Belarusian authorities in this case give grounds to believe that these minor breaches are used solely as a pretext to punish Ms Tonkacheva for her principled position and long-term human rights work and either to stop or create considerable obstacles in her human rights activities.

In this connection, we appeal to the Belarusian authorities to:

− Repeal the decision to cancel Ms Tonkacheva’s residence permit and not to deport her from Belarus;

− Take effective measures to protect human rights defenders and provide them with a possibility to carry out their human rights activities without any obstacles, as stipulated in the UN Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms from 9 December 1998;

− Be guided by the recommendation of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus to “recognize the important role of human rights defenders, whether individuals or members of civil society organizations, and guarantee the independence of civil society organizations and human rights defenders, enabling them to operate without

the fear of reprisal.”1

Sincerely,

Index on Censorship

1 A/69/307 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus

CC.

President of the Republic of Belarus

Aliaksandr Lukashenka

Belarus, 220016, Minsk, K.Marks Str., 38

Fax + 375 17 226 06 10

E-mail: [email protected]

Minister of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Belarus

Ihar Shunevich

Belarus, 220030, Minsk, Gorodskoy Val Str., 4

Fax + 375-17-218-76-02

E-mail: [email protected]

Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs

Main Internal Affairs Directorate of Minsk Municipal Executive Committee

Belarus, Minsk, Nezavisimost Ave, 48Б

Fax +375-17 331-81-6

E-mail: [email protected]

Department of Citizenship and Migration

Pervomajski District Office of Internal Affairs of Minsk

Belarus, Minsk, Belinski Str., 10

Fax+375-17-280-01-62

04 Nov 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Azerbaijan Statements, News and features, Statements

In the latest example of Azerbaijan’s crackdown on independent media, Khalid Garayev was detained by police on Oct 30, 2014.

On 30 October a Baku court sentenced opposition journalist Khalid Garayev to 25 days in detention on trumped-up charges of hooliganism and disobeying the police, dealing a new blow to Azerbaijan’s independent media at a time when its civil society is being subjected to an unprecedented crackdown.

A reporter for the leading opposition daily Azadliq, which was named the 2014 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Journalism award winner, and producer of “Azerbaycan Saati,” a TV programme linked to the newspaper that is broadcast by satellite from abroad, Garayev was sentenced just a day after his arrest.

Index on Censorship, International Media Support, Freedom House, Media Diversity Institute, Article 19, European Federation of Journalists, WAN-IFRA and Reporters Without Borders – all members of the International Partnership Group on Azerbaijan (IPGA) – call for Garayev’s release on appeal and condemn the witchhunt against journalists who work for Azadliq and “Azerbaycan Saati.”

Arrested on the evening of 29 October in the Baku suburb of Binagadi, Garayev was charged under articles 296 and 310.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences. The indictment said he was heard using vulgar language outside a supermarket in the centre of Binagadi and refused to comply with instructions from the police.

Appearing in court on 30 October, one of the two prosecution witnesses was a person who is apparently systematically used by the police in similar cases. The court rejected the defence’s request to view surveillance camera footage.

The sentence of 25 days in prison is close to the maximum of 30 days for such offences, for which the penalty can be just a fine. Garayev and his lawyer, Bakhruz Bayramov, accused the authorities of fabricating the entire case just to punish Garayev for his journalistic activities.

Azadlig and “Azerbaycan Saati” have long been subjected to harassment. The newspaper, which is being throttled economically, has had to suspend its print edition on several occasions and is now near to closure. Its editor, Ganimat Zahid, spent two and a half years in prison, from November 2007 to March 2010, on similarly trumped-up charges.

Amid mounting repression, the staff of “Azerbaycan Saati” have been singled out in recent months and one of its presenters, Seymour Khazi, has been in pre-trial custody since 29 August and is facing the possibility of three to seven years in prison on a charge of “aggravated hooliganism.”

A colleague, Natig Adilov, fled the country after his brother was arrested in August.

For more information about the crackdown on Azerbaijan’s civil society, read the recent IPGA report “Azerbaijan – when the truth becomes a lie.”

Signatories:

– Article 19

– European Federation of Journalists

– Freedom House

– Index on Censorship

– International Media Support

– Media Diversity Institute

– Reporters Without Borders

– WAN-IFRA

04 Nov 14 | ArtFreedomWales, Events

At the end of Index on Censorship’s ArtFreedomWales’ second online discussion (watch it in full above) there was a general consensus that they were just scratching the surface of a huge, important subject.

Hosted by Bethan Jones Parry (Broadcaster, Journalist and Writer), the following met online to discuss the opportunities and obstacles to expression for artists working in Welsh:

- Mari Emlyn (Artistic Director Galeri, Caernarfon)

- Arwel Gruffydd (Artistic Director Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru)

- Bethan Marlow (Playwright and Storyteller)

- Iwan Williams (Independent Creative Producer and Creative Development Officer for Mentrau Iaith Cymru)

The live broadcast opened with Jones Parry asking what censorship meant to each individual? Williams kicked off by saying he felt that culture in Wales isn’t censored from the outside but rather from the inside – self-censorship. Emlyn agreed that self-censorship is what she is most aware of despite there being examples of censorship in everyday life. To her censorship is stopping or restricting opinion and the spreading of that opinion. Marlow expressed, although not sure if it is censorship entirely, that when writing in Welsh there is a pressure and an awareness that the whole audience must be taken in to consideration and that you must please the whole audience. It is not confined to the theatre alone. Working within the Welsh language and trying to appeal to everyone can affect the work that is created and dilute it in some way. Jones Parry asked Gruffydd if he had a free voice as Artistic Director of Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru or is his voice censored. Gruffydd answered by saying that he hopes the company is giving writers and artist an uncensored voice however that there is a sense of self-censorship amongst writers and artists when working in Welsh especially with those who work bi-lingually. He noted two examples. One writer saying he didn’t want to write for the Welsh theatre because he had nothing to say about Wales – leading to the question must writing in Welsh be about writing about identity? The other example, a playwright who didn’t want to express themselves in Welsh because they had too much respect for the Welsh audience. They didn’t want to offend by disclosing some of the things lurking in their head! “Something’s are more difficult to share in Welsh.” Jones Parry concluded from the initial response that censorship is a very interesting mixture but what is apparent, despite there being an inherent censorship by any state regarding culture, in Wales, censorship mostly comes from self-censorship.

Jones Parry moved on by quoting David Anderson, Director General of National Museum Wales. “We are in the second decade of the twenty first century, but we still retain the highly centralized, nineteenth century, semi-colonial model that the arts should be concentrated in London, and that funding London is synonymous with serving the English regions and the nations of the UK. For Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland this undermines the principle, embedded in law, that culture is a devolved responsibility. It is a constitutional tension that remains unresolved.” The panel were asked to respond. Williams agreed that the funding model is centred on London and Cardiff and that there is always a pull towards the cities but that it was up to the companies and artists to change things – the ethos being to create the quality of work created in London in small rural areas of Wales. Jones Parry asked if the budget is less is it possible to achieve and offer the same quality? Williams agreed that budget is a huge factor but that confidence is a factor too. “We need to be ambitious and take big strides with our projects. By being ambitious, and if the will is there, we can create something that is of the same quality as anywhere else in the world.”

Responding to the question ‘Do Welsh speakers suffer, budget wise, because there are fewer Welsh speakers than English speakers?’ Gruffydd expressed “If you want to explore and experiment and strive towards new things with work and text – in a larger environment, with more people aware and more people buying a ticket that funds the work then a momentum is created. It is very difficult to express yourself in Welsh if your ideas are a little leftfield because we are a small audience when we are a full audience. If we break it down again to experimental work, certain texts, creating projects that appeal due to their nature then we are performing to two people and their dog. It’s difficult to fund that work.”

Marlow was asked how her work is perceived away from Wales to which she noted that the same recognition did not exist. Work away from Wales for her has always been an invitation from a company and not bringing previously performed work in Wales to England. She shared her frustration on searching for an agent that despite having many Welsh language credits including productions for high profile companies such as Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru, Sherman Cymru and TV companies, it was difficult to gain interest away from Wales. She believes the same gravitas for these big companies in Wales did not translate away from Wales. However, she believes “ as artists we don’t treat our companies with the same gravitas either. It’s important we have that pride of working in Wales and change our attitudes to see that a play produced by Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru is just as impressive as having work produced in London.” Jones Parry questioned that as a nation working in Welsh did our insecurity lead to self-censorship? Williams stated “Historically the language has been trampled on over the years. Our confidence as a nation is low. Since devolution there is a new sense of confidence and pride but a lot of work to be done still for us to believe in ourselves. It takes time and it’s not done overnight but we need to share big ideas and say big things.” Williams notes too that the creative sector in Wales is small and everyone knows each other. The critique of the work that happens in larger cultures doesn’t exist in Wales. “We censor the work we create as well as censor what we say about other people’s work.” Emlyn agrees. “As a small nation we are all afraid to offend. We all know each other. “ She believes that we must reach a point where we overcome the fear of offending. “There is a tendency to write safe things that doesn’t cause a stir or uproar. Conversation and interest is good. It gives us the drive to push boundaries and create something a bit more daring. Criticism is a problem in Wales. Either the fear of insulting or reviews become extremely personal.” Emlyn believes that there isn’t enough theatrical and historical background by theatre reviewers in Wales. She claims poetry and literature reviews are much stronger within the Welsh language.

Leading on from this, Gruffydd was asked as a director if he censors himself and compromises his principles by producing work that is popular and provides bums on seats. Gruffydd stated it is difficult to rate how much he censors himself. He has his own view and leaning as a director that reflects his personal artistic leaning, opinion and politics despite trying to remain impartial. During his tenure as Artistic Director of Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru he has chosen plays and texts that have pushed the boundaries for example ‘Llwyth’ (Tribe – about a group of gay male friends in Cardiff). Marlow rejected Jones Parry’s assumption that there are times she has wanted to express something but didn’t as it wouldn’t allow her to make a living. As a writer she has always said what she wanted. She can’t write if it is fueled by a fee alone. Marlow feels lucky to have been supported by companies that have allowed her to be open and to share what she wants to express. She believes nurturing a relationship is important. “Wales is different to the rest of Britain. The work is different and what is being said is different and that people in Europe can identify with the work.” Gruffydd believes that the English censor Welsh language work more than other cultures, due to, in his opinion old preconceptions. He notes that English culture needs to check on their perspective of Welsh work and Welsh culture. As a company it was easier for Theatr Genedlaethol to attract an audience in Taipei than London. “There is a lack of preconception abroad. It would be difficult to sell a production in Welsh to a non-Welsh audience in Cardiff let alone London and yet in Taipei the play ‘Llwyth’ attracted an audience of 1000.”

Emlyn was asked if it was difficult to attract work from across the border and overseas to Galeri in Caernarfon, North Wales suggesting that geography takes a practical hand in censorship. Emlyn didn’t believe so. Galeri has established itself as a strong centre with a mixed programme. Work from elsewhere has inspired local performers. As an example Emlyn explained how a visit from Sadler Wells company, ‘Company of Elders’ inspired a collective of women over sixty, who felt they had no platform to express themselves, to create a dance piece at Galeri. Emlyn notes it is not just geography but age, illness and so on that can lead to censorship and people feeling frustrated and restricted and therefore censored. Remaining on the subject of geographical censorship Gruffydd stated that ‘every road does not lead to Cardiff.’ As a National company he feels it’s important to invest in communities and supply them with important and substantial productions and not focus specifically on the main centers alone. The company’s latest production ‘Chwalfa’ will only play at Bangor. “It is up for the audience to travel to experience the story of that specific community.”

Jones Parry was interested to know if the story of the non-Welsh speaking Welsh was being heard within the arts and if it was balanced with the Welsh language Welsh story. Marlow’s opinion was that having two National Theatre Companies proves the output is balanced and her experience of working extensively with Welsh speaking and non-Welsh speaking communities in Wales also proved that. She believes both have a strong presence and voice. Emlyn noted that Welsh language productions sell out at Galeri but it is very difficult to attract an audience to English language theatre if the productions are from Wales or beyond. She believes that a Welsh language audience trust what they will get from Welsh language companies and play it safe. She was unsure why as if someone had a genuine interest in theatre surely they would attend productions in any language?

Bringing the discussion to a close Jones Parry asked all panellists for their final word. Gruffydd finalised his thoughts by stating that every culture censor themselves. “Culture on the whole has always favoured the middleclass and educated. People who do not fit in to this assumption or norm don’t feel as secure expressing themselves because of fear. It is a challenge for us in the arts to help overcome this and give a wider geographic the voice to express themselves artistically. The arts should belong and be beneficial to everyone’s everyday life.” Marlow ended her contribution by urging Wales to be brave and stop comparing themselves to any other country. Williams concluded by saying that culture and the arts need to be taken to the communities in order for attitudes to change. “Attitude needs to change and will change by sharing towards culture and the language.” He strongly believes communities are the key and to invest in public work beyond the usual paths of theatre and TV. Emlyn ended by stressing that Wales shouldn’t be scared of venturing. “The arts are there for us to express ourselves. If we can’t express ourselves in the arts where can we? We have the right to fail. Only by failing do we learn. We shouldn’t be afraid.”

Follow and participate in the discussions @artfreedomwales.

Find out more about Index’s UK arts programme.

This article was posted on November 01, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

03 Nov 14 | Latvia, News and features, Religion and Culture, Russia, United Kingdom

Protest outside the Royal Albert Hall in London over the recent concert staged by Russian singer Valeriya (Photo: Lensi Photography/Demotix)

At first glance, there seems to be little that Latvia’s New Wave music festival and London’s iconic Royal Albert Hall would have in common.

The former is hugely popular contemporary music festival and talent spotting contest on the shores of the Baltic Sea, attracting thousands of revellers from Eastern Europe and beyond. The latter is one of the world’s most famous venues, where some of the global music industry’s biggest and best artists regularly perform. It is also home to the Proms, the premier musical event of the British establishment.

But both have recently been embroiled in the fallout from the crisis in Ukraine, as a culture war between Russia and the west threatens to widen.

Last week it was claimed by Russia’s culture minister that the New Wave festival was on the verge of being cancelled and moved to Russia after three of the headline acts were barred by the Latvian government earlier this year.

The New Wave festival in the town of Jurmala was due to see Oleg Gazmanov, Joseph Kobzon and Alla Perfilova, known as Valeriya, perform in July.

According to the Baltic Times, the trio were banned from attending by the Latvian foreign ministry over their pro Russian views on the Ukraine crises. At the time several members of the Russian State Duma called on the festival to be moved to another Russian seaside resort, and suggested Crimea as an alternative.

“Concerning the organisation of ‘New Wave’ in Crimea, we are ready to cooperate and will gladly host any creative project in Crimea,” Crimea’s Culture Minister Arina Novoselskaya was quoted as saying.

But Russia’s Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky has reopened the debate by suggesting that the festival is now on the verge of being moved permanently.

“This decision by the Latvian powers that be can be regarded with nothing except astonishment, and as a result, Jurmala stands to suffer serious economic losses,” he told the Baltic Times while at a private meeting in the capital Riga. “We are very close to making the decision to exit, because Russian artists will not tolerate such a slap in the face.”

The six day concert, which gives emerging artists around the world a chance to perform in front of large crowds, was started in 2002 and is considered one of the best in the region. Thousands attend the event and prizes for the winners can be in their tens of thousands of euros.

But big stars attend too.

Kobzon – once dubbed “Russia’s Frank Sinatra” and who is now a Russian MP – said that he was going to file a lawsuit at the European Court of Human Rights over his ban. “I’m suing the Latvian government for moral and material damages,” he told Pravda. “I had paid the hotel 11,500 euros for the time of my stay in Jurmala, but the hotel did not return the money to me.”

The Latvian foreign ministry released a statement at the time that said the three singers “through their words and actions have contributed to the undermining of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.” Latvian Foreign Minister Edgars Rinkevics sent a tweet that “apologists of imperialism and aggression” would be denied entry into Latvia for the festival. The tweet appears to have been deleted.

The issue has once again raised its head after a campaign was launched by anti-Putin activists to have several Russian artists banned from performing in the UK too. Both Kobzon and Valeriya, who were billed to play at a special one-off concert at London’s Royal Albert Hall on 21 October, were again targets of the proposed bans.

According to The Guardian, both artists signed an open letter supporting Putin’s controversial policies in Ukraine. In the week running up to the concert, Valeriya was pictured sitting next to Putin at the Russian F1 Grand Prix.

The London concert went ahead, though it would seem, not exactly as planned. Kobzon reportedly decided to not attend at the last minute, allegedly fearing he would be turned away at the UK border. Over 100 Ukrainian activists picketed the concert, holding placards that read: “Ukrainian Blood on Putin’s Hands” and “Valeria [sic] and Kobzon: Putin’s Voices of War and Death”.

“After the concert we asked some of the people who attended what was said, as they were leaving. They told us Kobzon didn’t perform, “Nadia Pylypchuk, from the London Euromaidan campaign group who organised the protest, told Index on Censorship. “Valeriya told them on stage that Kobzon couldn’t be there because of ill health. But a few days later he performed in Eastern Ukraine. He was just scared that he would not be allowed into the country,” she added.

Despite several attempts by Index to contact the Royal Albert Hall, the venue declined to answer questions about the concert, including whether Kobzon had performed.

A week later, Kobzon, who was born in the Donbass region, would be banned from entering Ukraine by the Kiev government. He nevertheless returned through the porous Russian border, which the Kiev government has little control over, to perform a concert at the Donetsk Opera House.

According to Buzzfeed he was joined on stage by rebel leader Alexander Zakharchenko for the Soviet classic I Love You, Life. Although Zakharchenko was clearly a little rusty. “It’s fine,” Kobzon reassured him after the performance. “I’m an even worse soldier than you are a singer.”

For activists back in the UK, the London concert was proof that Russia’s elite preaches one message to his home audience, whilst acting very differently abroad.

“Such hypocrisy is unacceptable,” Andrei Sidelnikov, an anti-Putin activist who has been given political asylum in the UK and who started the campaign to have the concert scrapped, told The Guardian. “In Russia, they declare that western values are bad, wrong, and not suitable for Russia. Then they travel to western countries to earn money, spend holidays, and buy real estate.”

This article was originally posted on 3 November at indexoncensorship.org

02 Nov 14 | Campaigns, Russia, Statements

Aleksandr Bastrykin

Head of the Investigative Committee of Russian Federation

The Investigative Committee of Russian Federation

105005, Russia, Moscow, Technicheskii Lane, 2

Sunday 2 November 2014

Dear Mr Bastrykin,

RE: Request for investigation into the murder of Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev to be transferred to the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee.

On the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists (2 November) we, the undersigned organisations, are calling upon you, in your position as Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, to help end the cycle of impunity for attacks on those who exercise their right to free expression in Russia.

We are deeply concerned regarding the failure of the Russian authorities to protect journalists in violation of international human rights standards and Russian law. We are highlighting the case of Ahkmednabi Akhmednabiyev, a Russian independent journalist who was shot dead in July 2013 as he left for work in Makhachkala, Dagestan. In his work as deputy editor of independent newspaper Novoye Delo, and a reporter for online news portal Caucasian Knot, Akhmednabiyev, 51, had actively reported on human rights violations against Muslims by the police and Russian army.

His death came six months after a previous assassination attempt carried out in a similar manner in January 2013. That attempt was wrongly logged by the police as property damage, and was only reclassified after the journalist’s death. This shows a shameful failure to investigate the motive behind the attack and prevent further attacks, despite a request from Akhmednabiyev for protection. The journalist had faced previous threats, including in 2009, when his name was on a hit-list circulating in Makhachkala, which also featured Khadjimurad Kamalov, who was gunned down in December 2011. The government’s failure to address these threats is a breach of the State’s “positive obligation” to protect an individual’s freedom of expression against attacks, as defined by European Court of Human Rights case law (Dink v. Turkey).

A year after Akhmednabiyev’s killing, with neither the perpetrators nor instigators identified, the investigation was suspended in July 2014. As well as ensuring impunity for his murder, such action sets a terrible precedent for future investigations into attacks on journalists in Russia. ARTICLE 19 joined the campaign to have his case reopened, and made a call for the Russian authorities to act during the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) session in September 2014. During the session, HRC members, including Russia, adopted a resolution on safety of journalists and ending impunity. States are now required to take a number of measures aimed at ending impunity for violence against journalists, including “ensuring impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations, which seek to bring to justice the masterminds behind attacks”.

While the Dagestani branch of the Investigative Committee has now reopened the case, as of September 2014, more needs to be done in order to ensure impartial, independent and effective investigation. We are therefore calling on you to raise Akhmednabiyev’s case to the Office for the investigation of particularly important cases involving crimes against persons and public safety, under the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee.

Sadly, Akhmednabiyev’s case is only one of many where impunity for murder remains. The investigations into the murders of journalists Khadjimurad Kamalov (2011), Natalia Estemirova (2009) and Mikhail Beketov (who died in 2013, from injuries sustained in a violent attack in 2008), amongst others have stalled. The failure to bring both the perpetrators and instigators of these attacks to justice is contributing to a climate of impunity in the country, and poses a serious threat to freedom of expression.

Cases of violence against journalists must be investigated in an independent, speedy and effective manner and those at risk provided with immediate protection.

Yours Sincerely,

ARTICLE 19

Amnesty International

Albanian Media Institute

Association of Independent Electronic Media (Serbia)

Azerbaijan Human Rights Centre

Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

Center for National and International Studies (Azerbaijan)

Civic Assistance Committee (Russia)

Civil Society and Freedom of Speech Initiative Center for the Caucasus

Committee to Protect Journalists

Glasnost Defence Foundation (Russia)

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor (Armenia)

Helsinki Committee of Armenia

Human Rights House Foundation

Human Rights Monitoring Institute (Lithuania)

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino-Kyrgyzstan”

Memorial (Russia)

Moscow Helsinki Group

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

Index on Censorship

International Partnership for Human Rights

International Press Institute

International Youth Human Rights Movement

IREX Europe

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

Kharkiv Regional Foundation – Public Alternative (Ukraine)

PEN International

Public Verdict Foundation (Russia)

Reporters without Borders

The Kosova Rehabilitation Center for Torture Victims

World Press Freedom Committee

cc.

President of the Russian Federation

Vladimir Putin

23, Ilyinka Street, Moscow, 103132, Russia

Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation

Yury Chaika

125993, GSP-3, Moscow, Russia

st. B.Dmitrovka 15a

Minister of Justice of the Russian Federation

Alexander Konovalov

Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation

119991, GSP-1, Moscow, street Zhitnyaya, 14

Chairman of the Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights

Mikhail Fedotov

103132, Russia, Moscow

Staraya Square, Building 4

Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation for the Republic of Dagestan

Edward Kaburneev

The Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation for the Republic of Dagestan

367015, Republic of Dagestan, Makhachkala,

Prospekt Imam Shamil, 70 A

Ambassador of the Permanent Delegation of the Russian Federation to UNESCO

H. E. Mrs Eleonora Mitrofanova

UNESCO House

Office MS1.23

1, rue Miollis 75732 Paris Cedex 15

01 Nov 14 | Draw the Line, Events, United Kingdom

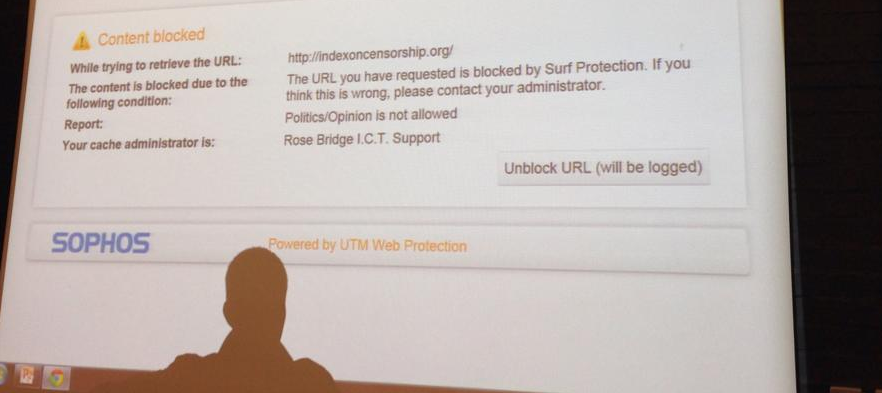

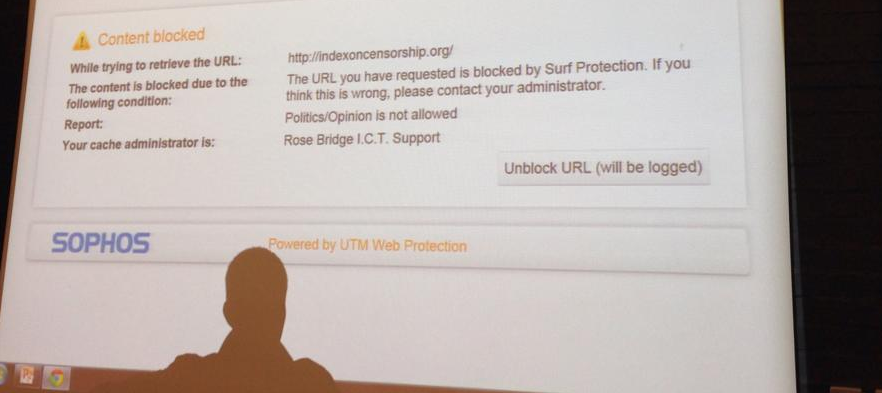

Index held a successful workshop with the north west contingent of the British Youth Council, despite the inability to access our own website because of internet filtering at the location.

Index held a third Draw the Line workshop with the British Youth Council, but this time with its groups in the north west of England at their regular regional convention. Before the workshop began we faced a problem — we couldn’t get onto our website. The convention was held in a local secondary school and the school’s server was blocking our website. This is unusual, but with highly sensitive school internet filters it was possible that there were too many words deemed unsuitable for children used on our website. This filter appeared to be more sophisticated and specified the reasoning behind blocking our content: “Politics/Opinion is not allowed”.

It was difficult to test how far this stretched, but it was alarming that politics or opinion would be blocked at a school limiting its pupils’ ability to research different points of view.

We spoke to youth workers at the convention who said they faced similar problems when trying to do projects with young people on LGBTQI issues or drugs. The filters were so sensitive that they would not even allow students access to the websites of support groups which cover these issues, it simply blocked them all.

Despite the censor’s best efforts this made a great starting point for the debate and demonstrated to the participants the levels of censorship that we all face in our daily lives. The groups were able to articulate many different current and historical instances of censorship from wartime propaganda to being forced to wear a school uniform and understood why freedom of expression is fundamental to human rights.

The discussion moved onto the latest Draw the Line question, “Are voting restrictions a violation of human rights?” The members enthusiastically debated the prospect of voting at 16 (this is one of the British Youth Council’s campaigns) with the group still split on whether this should be implemented into UK law. There was also a great opportunity to discuss these issues with the youth workers in the region and find out how social media restrictions can both harm and protect children and how we can begin to define the difference.

Wigan pier is one of the unique locations around the world where the Index on Censorship magazine is available to download for free. It was nominated as a free speech spot because of George Orwell’s novel, The Road to Wigan Pier. Find out more on how to download your copy here.

This article was posted on 12 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Oct 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Turkey

Cartoonists like Ben Jennings rallied around Musa Kart when he faced jail over a caricature of Turkey’s President Erdogan (Credit: Ben Jennings)

Not long ago Turkish cartoonist Musa Kart faced the prospect of spending nine years behind bars, simply for doing his job.

Taken to court by the Turkey’s President (and former Prime Minister) Recep Tayyip Erdogan himself, Kart last week stood trial for insult and slander over a caricature published in newspaper Cumhuriyet in February. Commenting on Erdogan’s alleged hand in covering up a high-profile corruption scandal, the cartoon depicted him as a hologram keeping a watchful eye over a robbery.

While Kart was finally acquitted last Thursday, his case was just starting to hit international headlines — in no small part due to the swift reaction from colleagues around the world. In the online #erdogancaricature campaign initiated by British cartoonist Martin Rowson, his fellow artists shared their own drawings of the president. With Erdogan reimagined as everything from a balloon, to a crying baby, to Frankenstein’s monster, the show of solidarity soon went viral.

“This campaign has showed me once again that I m a member of world cartoonists family. I am deeply moved and honoured by their support,” Kart told Index in an email.

Kart has been battling the criminal charges since February. His defiance was clear for all to see when he told the court on Thursday that “I think that we are inside a cartoon right now”, referring to the fact that he was in the suspect’s seat while charges against people involved in the graft scandal had been dropped.

He remains defiant today: “Erdogan would have either let an independent judiciary process to be cleared or repressed his opponents. He chose the second way,” he said. “It’s a well known fact that Erdogan is trying to repress and isolate the opponents by reshaping the laws and the judiciary and by countless prosecutions and libel suits against journalists.”

This isn’t the first time Kart has run into trouble with Erdogan. Back in 2005, he was fined 5,000 Turkish lira for drawing the then-prime minister as a cat entangled in yarn. The cartoon represented the controversy that surrounded Turkey’s highest administrative court rejecting new legislation that Erdogan had campaigned on.

“I have always believed that cartoon humour is a very unique and effective way to express our ideas and to reach people and it contributes to a better and more tolerant world,” he explained when questioned on where he finds the strength to keep going.

It remains unclear whether the story ends with this latest acquittal decision. While the charges against Kart were dropped earlier this year, an appeal from Erdogan saw the case reopened. “Erdogan’s lawyers will…take the case to the upper court,” he said.

Kart’s experience is far from unique; free expression is a thorny issues in Erdogan’s Turkey. In the past year alone, authorities temporarily banned Twitter and YouTube and introduced controversial internet legislation. Meanwhile journalists, like the Economist’s Amberin Zaman, have been continuously targeted, as Index on Censorship’s media freedom map shows.

Kart is not optimistic about the future of press freedom in his country: “Unfortunately, day by day, life is getting harder for independent and objective journalists in Turkey.”

This article was originally posted on 31 October at indexoncensorship.org

30 Oct 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

![(Photo: Cindy (Flickr) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Happy_Halloween.jpg)

(Photo: Cindy (Flickr) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Paisley was, as usual, horrified by the world. That particular week he had one thing in mind: “Rock music is satanic,” Paisley told the assembled. “Let me repeat that, rock music is satanic, and those who have studied it have proved that conclusively.”

The reverend’s attention had been drawn back to rock music by the visit to Belfast of heavy metal singer Ozzy Osbourne. Osbourne had, Paisley intoned, been “sacked by another satanic organisation called ‘Black Sabbath'” for his drinking. And now this man was on Paisley’s territory.

“[It] is the intention of the devil to carry the battle for youthful minds, for youthful hearts and for youthful bodies. The citadel of man is his soul, and the battle is on in this city for the souls of the youth of our city.”

Paisley was a man capable of seeing demons everywhere but in himself, but he was not alone in his conviction that satan himself was acting through music and other media to destroy young minds (though he may have been alone in his later belief that line dancing induced lustfulness).

The mid 80s and early 90s were a time when many people seemed convinced that pop musicians were having weekly conference calls with beelzebub on how to corrupt and destroy the world’s youth. Osbourne’s fellow Brummie rockers Judas Priest found themselves accused of causing the suicides of two young fans by planting subliminal messages in their records.

(Meanwhile, in an atmosphere of moral panic, Tipper Gore and her comrades at the Parents Music Resource Center were diligently seeking out the rude bits on every record released and taking careful note, like schoolboys who’d found a discarded copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Pressure from the PMRC would lead to the “Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics” stickers put in the cover of every fun record released between 1985 and 1995, and contributed to the atmosphere where Miami Bass act 2 Live Crew found themselves in the dock for obscenity over their album As Nasty As They Wanna Be, the lewd content of which even the black and white stickers did not provide adequate warning for, it was claimed. Aptly, the song S&M on the 2 Live Crew album Move Somethin’, which preceded As Nasty As They Wanna Be, contained the lyric “I’m a disciple of Satan, with work to do”.)

One could argue that it’s a bit much to call your band Black Sabbath and then complain about being demonised. But it’s not just bat-biting metal bands that have faced accusations of evildoing.

William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, based on the novel of the same name, is one of the most Christian films ever made. Portraying the demonic possession of a young girl, what’s fascinating in watching The Exorcist now is how little of it is actually concerned with the “exorcism” itself. Huge chunks of the film are used in watching the priest Father Damien Karras explore every other avenue for the girls physical and mental state apart from possession. It is only in the last third of the film that the exorcist of the title appears, and the demon possessing the child is finally defeated. “You can have all the education and science you want,” The Exorcist suggests, “but only faith in God will save you from evil.”

This message would, you think, find favour with Christians. And yet Pastor Billy Graham, one of the UK’s most powerful preachers at the time of the film’s release in 1973, was appalled by The Exorcist. According to William Peter Blatty, who adapted the screenplay for The Exorcist from his own novel, Graham believed “’There [was] a power of evil in that film, in the fabric of the film itself.” Protestant evangelist Graham’s view of the film may not have been helped by it’s overt Roman Catholicism.

The Catholic church itself has recent form in perceiving satan at work. In 2003, then-cardinal and future pope Joseph Ratzinger reportedly denounced JK Rowling’s Harry Potter books as a “subtle seduction” which had “deeply unnoticed and direct effects in undermining the soul of Christianity before it can really grow properly”.

Later, in 2008, a Catholic academic put it rather more bluntly. Writing in the Vatican’s L’Osservatore Romano newspaper, Edoardo Rialti commented that: “Despite the values that we come across in the narration, at the base of this story, witchcraft is proposed as a positive ideal.

“The violent manipulation of things and people comes thanks to knowledge of the occult.”

Happily, like many an exhausted parent before it, the church eventually came to love the boy wizard and his Blytonian adventures. By the time the film of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was released, L’Osservatore Romano was full of praise, saying: “There is a clear line of demarcation between good and evil and [the film] makes clear that good is right. One understands as well that sometimes this requires hard work and sacrifice.”

By this time, again like many an exhausted parent, the Vatican had moved on to the new territory of the Twilight saga. One Monsignor Perazzolo of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council warned that the vampires v werewolves film’s occultery could create a “moral void more dangerous than any deviant message”. This, of course, was the same series that faced heavy criticism for creator Stephenie Meyer’s apparent Mormon undertone of sexual abstinence.

Satan and the occult trump all when hand wringing is to be done, with the sole exception of accusations of paedophilia (the history of real, dangerous and false allegations of paedophilia linked to satanic ritual in the UK is for a separate article). The very personification of evil is still a significant presence even in our secular lives. But he is invoked more often than not by those who wish to see his hand in simple things they do not like or do not understand.

This article was posted on 30 October 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![People taking part in the funeral procession of Lasantha Wickrematunge (By Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Lasantha_Wickrematunge_funeral_banners_1.jpg)

![(Photo: Cindy (Flickr) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Happy_Halloween.jpg)